3D bioprinting the human chest wall: Fiction or fact

Introduction

Surgical resection of a skeletal chest wall tumour requires a wide local excision of the tumour and full thickness resection of the chest wall to ensure tumour free margins, minimize local recurrences and contribute to long-term survival1. However, a wide local excision and full thickness resection of the chest wall results in a large defect. Reconstructing this defect anatomically is essential to minimize thoracic deformity, restore the normal anatomical shape and structure of the chest wall, preserve its protective and respiratory functions and when indicated, allow patients to receive adjuvant radiotherapy2,3. The reconstruction is complex and challenging, and requires a combination of pleural and skeletal reconstruction with soft tissue cover3,4,5. Traditionally the skeletal reconstruction has been performed using various techniques including a mesh and methyl-methacrylate cement prosthesis3,4.

3D printing—the new kid in town

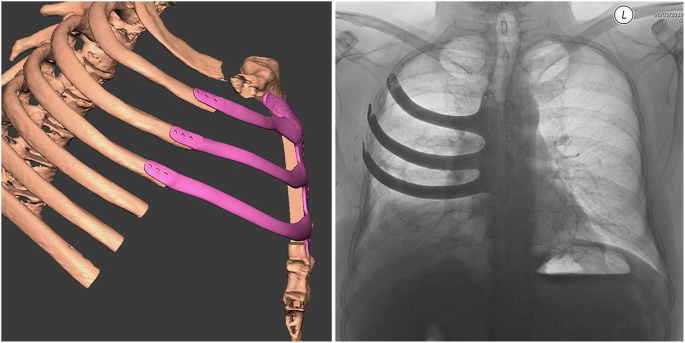

At our center, we have successfully carried out chest wall reconstruction of large, surgically created defects using anatomically designed, 3D printed ribs and sternum implants in titanium [Fig. 1]5,6,7,8. To plan the surgical resection and reconstruction and design the implant, sub-millimetre slice Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) computed tomography (CT) scan data is imported into Mimics Medical 20.0 software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) and by manual bone threshold segmentation, a 3D virtual model of the patients’ chest wall with the tumour is created5,6,7. The stereolithographic file of the model is then imported into Geomagic Freeform Plus software (3-D Systems, Rock Hill, United States) to plan the extent of resection required, which is carried out by digitally growing the tumour by 2 cm in order to achieve all around tumour free margins5,6,7.

The 3D implant was fashioned and designed in the anatomical image of the sternum, costal cartilages and ribs being resected using Geomagic Freeform Plus software.

The replacement 3D implant is then fashioned and designed in the anatomical image of the sternum, costal cartilages and the ribs being resected with Geomagic Freeform Plus software (Fig. 1)5,6,7. To secure the implant to the sternum and ribs, multiple fixating holes are added to the implant design. The edges on the underside of the implant are designed as rabbeted edges (stepped edges) for the implant to sit on the bone stumps and slot into the defect precisely (Fig. 1)5,6,7. To in-house test the design, a prototype of the implant and anatomical model of the healthy ribs and sternum are printed in dental surgical-grade material (Formlab, MA, USA). If satisfactory, the replacement 3D titanium implant is finally manufactured using TiMG 1 powder fusion 3D direct metal laser sintering technology5,6,7. To achieve precise surgical resection, customized cutting guides in titanium are similarly fabricated to guide surgical resection at surgery. The prototype of the implant and the implant itself are also available at surgery as a reference guide.

By adopting 3D printing technology for planning the surgical resection and subsequent reconstruction of the chest wall, one can achieve precise resection of the chest wall with clear all around margins, and for the customized implants to then fit into the defect perfectly5,6,7. Each implant is readily secured to the chest wall with interrupted Ethibond Excel® non-absorbable, braided, gauge 5 sutures or a combination of titanium screws and Ethibond Excel® sutures5,6,7. Following surgery and on follow up CT imaging, there is minimal deviation from the planned placement of the implant, as demonstrated by superimposing the post-operative in situ 3D volume rendered CT image of the implant on the pre-operative volume rendered CT image of the implant7. Hence, the anatomical shape and structure of the chest wall is restored with no resulting thoracic deformity and the protective function of the chest wall maintained with minimal risk of dislocation or paradoxical movement of the implant [Fig. 1]2,5,6,7.

3D bioconstruction of the chest wall

Custom made, anatomically designed and 3D printed titanium implants help restore the anatomical shape, structure, aesthetic appearance and protective function of the thoracic cage [Fig. 1]2,5,6,7,8. However, a large, rigid implant may restrict normal respiratory movements6. 3D printed dynamic implants with spring-like geometry may allow flexibility and physiological movement at respiration9. Movement over time, however, may predispose the implant to articulation related implant fracture, release of wear debris and metal ions7. Moreover, the porous flexible arches of the prosthesis9 may fill up with autologous tissue resulting in restriction of movement over time. Hence, a better solution would be bone and cartilage, which is a living tissue that grows and changes with the individual and comprises of the individuals own genetic material so there is no risk of rejection. Bone allografts and autologous grafts have previously been used4,10,11,12. Transplanting autologous bone integrates reliably with host bone and lacks the immune- and disease-related complications of allogeneic bone obtained from a human cadaver hence, provides a good clinical outcome12,13. However, obtaining autologous graft material requires surgical time, incurs morbidity, is costly, quality material is finite and the reconstruction is limited by the surgeons’ ability to contour delicate 3D shapes12,13. With the ability to 3D-print shapes with high fidelity and fabricate a scaffold tailored to the specific defect, 3D printing has emerged as a promising new approach for designing and manufacturing complex biological constructs in the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine14,15.

Bioprinting in regenerative medicine, is a subcategory of 3D printing. First named as ‘cytoscribing,’ it was the placement of cells contained within biomaterials (bioinks) into spatially defined structures using automated 3D bioprinting technologies16. In the past two decades, the definition of bioprinting has broadened as various bioprinting processes and process-compatible bioink materials have developed16,17. The introduction of bioinks containing cells and biomaterials, and the development of complex computer assisted design (CAD) and computer assisted manufacturing (CAM) systems have ushered in a new technology described as 3D bioprinting17. Guided by CAD-CAM, 3D bioprinting is described as a layer-by-layer precise positioning of biological materials, biochemicals and living cells, with spatial control of the placement of functional components, to fabricate 3D structures17. Thus, 3D bioprinting may provide a better living tissue alternative to 3D printed titanium implants to achieve an anatomical, aesthetical and functional reconstruction of the chest wall. To achieve this reconstruction would require, with CAD-CAM, the fabrication of an appropriately shaped 3D construct with 3D printing as described5,6,7,8,13,15,17,18,19,20,21.

The construct can be manufactured by using either (i) the top-down traditional tissue engineering approach of printing an acellular 3D scaffold of bone and cartilage, impregnated with bone and cartilage forming signals, which is then populated with tissue-forming stem cells prior to or at the time of implantation14,15,19,21, or (ii) the bottom-up and a more promising 3D bioprinting tissue engineering approach, where a computer aided designed, living, viable, cellular construct that is an exact replica of the area to be reconstructed, can be precisely fabricated17,22.

3D printed acellular construct and stem cells

Tissue engineering is the repair of lost or damaged tissues or organs and aims to regenerate the composition and structure of the native tissue by using an engineered construct or scaffold,17,23. The tissue-engineered scaffold provides the extracellular matrix (ECM) for the characteristic cell types of living bone tissue. Tissue engineering of bone or cartilage chiefly relies on three major components namely, fabricating a scaffold that mimics the native environment of the cells or tissues cultured within. The scaffold acts as a temporary extracellular matrix to promote cellular attachment, proliferation, differentiation and vascularization with subsequent ingrowth of cells until the tissues are totally restored or regenerated17,19,21,22,23,24,25. Secondly, a cell line that is capable of differentiation15,25 and thirdly, osteoinductive signals, generated by minerals, biomolecules and growth factors and required by the cell lines to accelerate differentiation and form vascularised bone and cartilage tissue17,19,21,22,23,24,25,26.

Scaffold

The preliminary step in the reconstruction of bone and cartilage involves the fabrication of a scaffold that mimics the macro- and micro-geometry of the area to be reconstructed13,23,24,26. A porous scaffold allows cells, blood vessels and nerve tissue to grow inside it to form healthy, living tissue13,23,24,26,27. Once new bone is formed the scaffold should biodegrade away with no toxic by-products13,28. The key parameters in the reconstruction of bone and cartilage include mimicking the precise anatomical shape, structure and the macro-geometry of the area of the chest wall; mimicking the bioactive micro-architecture of bone and cartilage; and constructed with materials that promote rapid bone and cartilage formation whilst ensuring the porous scaffold possesses sufficient strength and mechanical properties to prevent fracture under physiological loading conditions13,17,19,22,23,26. Recent advances in 3D printing technologies allow the generation of customized, anatomically shaped scaffolds with varying internal porosities using natural and synthetic polymers17,23,24,26.

Natural and synthetic biomaterials

Natural polymers, obtained from human and animal tissues, and synthetic polymers have been popular biomaterials used for fabricating scaffolds due in large part to their vast diversity of properties and bioactivity23,24,27,29,30,31. Natural polymers, due to their better overall interactions with various cell types and lack of an immune response were among the first biodegradable scaffold materials to be used clinically27. Natural polymers can be classified as proteins (collagen, gelatin, silk, fibrinogen, elastin, keratin, actin, and myosin), polysaccharides (cellulose, amylose, dextran, chitin and glycosaminoglycans), or polynucleotides32,33,34,35. Biopolymers such as gelatin and collagen, a main protein component of natural bone, consist of amino-acid sequences to which cells readily attach; the recipients’ cells are accustomed to remodelling; and enzymes able to bio-degrade these materials34,35. They exhibit several desirable characteristics such as the ability to be processed into micro-particles and nano-particles35. However, acquiring biopolymers from living source, their processing and ability to modify their undesirable properties, for example, their typically low mechanical strength and compositional variability, affects their commercialization35.

Synthetic polymers are however, cheaper and functionally superior than natural polymers, despite the potential for an immune response or toxicity especially with the use of certain polymer combinations32,33. Among the synthetic polymers, poly(caprolactone) (PCL), poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA), poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), and poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) are the most popular for the fabrication of 3D scaffold constructs28,32,35,36,37. Synthetic polymers offer more possibilities for chemical modifications and molecular alterations thus allowing their properties to be tailored to specific requirements35. For example, different synthetic polymers can have a predominance of either hydrophobic or hydrophilic properties, which affect their interactions with the aqueous physiological environment and can define their ability to form hydrogels versus non-hydrated polymeric structures35. Hydrophobic synthetic polymers tend to be osteoconductive rather than osteoinductive. Conversely, their hydrophobic properties reduce their potential for immunogenicity38. The biological functions of synthetic polymers can be altered by adding bioactive or cell adhesion peptides35,39.

Polymeric compounds with high mechanical strength that mimic native tissue and often used are silk protein, PLLA, chitosan nanofibers and bioactive glass materials21,24,29,33,36,37. Synthetic polymers used in combination with natural polymers, address the problems associated with hydrophilicity, cell attachment and biodegradability29,35. For bone regeneration, among the popular scaffold materials are hydroxyapatite, beta tri-calcium phosphate (b-TCP) and certain compositions of silicate and phosphate glasses (bioactive glasses), due to their structural similarities, compressive strength and osteoinductivity potential21,33,37.

In light of the composite nature of bone tissue and the complex requirements for bone-tissue-engineering materials, hybrid biomaterials and increasingly, composite biomaterials, owing to their ability to outperform their individual constituents offer promising biomimetic solutions35. 3D fabricated, highly porous scaffold constructs of nanofibers, hydrogels and sintered micro-particles have been explored40. For example, for a 3D printed nanofiber construct, small grain size, which refers to the size of each individual fragment of material used in the scaffold construct, enhances cellular attachment, proliferation and differentiation of most osteogenic cells40,41 as does the porosity of the scaffold40,42,43,44.

Porosity

Porosity is an important determining factor for cellular attachment, vascularization and growth42,43,44,45. Vascularization remains one of the key challenges for bone tissue engineering, as insufficient vascularization can lead to a strong deficiency of the critical nutrients for cell survival within a scaffold, and to unexpected and dangerous irregularities in differentiation45. Porosity plays an important part in promoting vascularization45. In order to achieve cellular attachment, a uniform distribution of cells within the scaffold, migration of cells within the scaffold, vascularization, ingrowth of cells and integration of regenerated tissues with the native tissues, the density of the pores, their geometry and pore size are manipulated to particular parameters, depending on the material and application43,44,46,47.

Higher porosity correlates with increased bone growth42,48 and a designed pore architecture, compared with a random architecture, results in higher pore connectivity and uniform distribution of cells within the scaffold despite similar porosity, pore size and surface area46,48. Increasing pore size increases vascularization, which is a critical component of tissue survival. Pore sizes between 160–270 μm result in extensive vessel formation in both mathematical and experimental models44,45,47,48. Within the scaffold, osteoblast proliferation and migration also depend on pore size, with larger pores of 300 μm resulting in higher cell numbers throughout the scaffold44,48. Increasing pore size and interconnectivity improves diffusion of nutrient into the scaffold and diffusion of waste out of the scaffold48,49.

Structural strength

Increasing porosity within the scaffold, however, lowers its mechanical properties and structural strength48,50. The primary aim of the 3D construct is to provide structural support to the cells and tissues growing within it and robust mechanical strength to the chest wall skeleton for the skeleton to withstand the stresses of physiological loads, and transduction of mechanical forces through the chest wall and the bony skeleton without fracturing7,50. Hence, porosity within the scaffold has to be carefully balanced with the required structural strength of the scaffold to prevent fracture of the construct under loading conditions.

The scaffold stiffness depends upon the Young’s moduli of ribs (inclusive of both trabecular and compact bone), the Young’s moduli of cartilage and the anatomical location of the reconstruction51,52,53. Young’s moduli of human ribs range between 10–17 GPa and cartilage, 700 kPa, and these compressive moduli within the target scaffold are required to achieve a robust reconstruction of the chest wall and prevent fracture under pressure50,51,52,53. Many current 3D-printed scaffolds have achieved stiffness within the 10–100 MPa range42,48,51,53.

Cell line capable of differentiation

For the scaffold to generate the appropriate extracellular matrix and form living tissue, the scaffold may be populated with for example, human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) isolated from an aspirate of bone marrow, which can form several types of tissues, bone and cartilage21,54,55,56 or with the individuals’ autologous multipotent human adult stem cells (hASCs)27,57,58,59,60,61. These hASCs may be obtained at the time of surgery from the individuals’ own, easily accessible and abundant store of adipose tissue21,60,61. Chondrogenic cells derived from hMSCs, as compared to adult chondrocytes, result in the less complete formation of cartilaginous tissue and tend to undergo hypertrophy and calcification21,55. Adult stem cells from adipose tissue59,60,61 and bone marrow54,62 possess a limited multipotent differentiation potential and are considered safer for clinical transplantation and autologous applications. Adipose stem cells obtained from fat tissue, for example, from liposuction patients, can be effectively harvested in large numbers; are genetically stable in long-term; have favourable immune-modulating functions, for example, in transplantation medicine; are more resilient compared to bone marrow stem cells; and can differentiate into cells of different lineages, namely, osteogenic, chondrogenic, myogenic, neurogenic and adipogenic lineages60,61,62. With established protocols for their isolation, expansion and differentiation, adipose hASCs are a promising cell source for seeding acellular bioprinted constructs. Following their harvest at surgery, it is essential to achieve an even distribution of the harvested cells within the scaffold in order to generate the appropriate ECM of living tissue and facilitate the regenerating tissue to mimic and maintain structure, physiology and long-term function of the chest wall. Future advances in cell culture techniques are likely to make use of other stem cell populations for bio-printing and making clinical applications a realistic possibility62,63.

Osteoinductivity of the scaffold

To ensure stem cells form bone and cartilage and not any other structure, biological osteoinductive signals to the resident cells are required, which are incorporated in the acellular scaffold at the time of 3D printing to guide the stem cells to form bone48,64. The biosignals for inducing osteogenesis and chondrogenesis are governed through various physical and chemical factors. To achieve osteogenesis, the most widely used strategy is the incorporation of mineral phases in the scaffold to induce osteoinductivity64. To create a mineralized structure that can house cells and provide signals to stimulate bone formation, minerals such as phosphoric acid binder to bind calcium phosphate65 and poly(caprolactone) combined with tricalcium phosphate particles, when incorporated at the time of 3D printing, stimulate bone formation66,67. In addition, incorporating bioactive molecules, for example, bone morphogenetic proteins and growth factors in the acellular 3D printed scaffold construct stimulates osteogenesis21,51,67. Since sintering methods are used for 3D printing, which rely on high temperatures of up to 1300 °C, use of growth factors in 3D printing remains a challenge48,67. One approach is to use chemical binding methods where 3D printing is achieved at room temperature. With careful choice of binder to prevent pH-related damage, growth factors can be incorporated at the time of printing48. A second approach is to load growth factors onto a scaffold post-printing, which circumvents these issues but adds another step to scaffold manufacturing process48.

With accurate control of the distribution of cells to generate the appropriate extracellular matrix, in vitro laboratory and in vivo animal experiments have shown that it is possible to achieve bone growth in the shape and structure required over five weeks13,48. Hence, it may be possible to provide surgeons with an anatomical, 3D printed, acellular scaffold, impregnated with osteoinductive bone-forming signals, which the surgeon can then populate with human adipose tissue stem cells obtained at the time of surgery13. Therefore, with a combination of tissue engineering and 3D printing, it may be possible to restore the natural shape, structure and physiological function of the chest wall by preparing 3D scaffolds prior to surgery and seeding the scaffolds with stem cells at surgery. However, a limitation is failure to achieve a uniform distribution of cells and hence, failure to generate the appropriate ECM. Without a proper ECM microenvironment, cells cannot function as tissues properly38,41. Hence, a more promising approach would be to build up tissues of the chest wall skeleton brick by brick, in a bottom-up approach using 3D bioprinting.

3D bioprinting living, viable cellular constructs

3D bioprinting, with computer aided designing, deposits cells and scaffold simultaneously to form a pre-designed, viable structure with micron scale precision48,68. This brick by brick, manufacturing process uses three central approaches to fabricate 3D biostructures17. Biomimicry, the manufacture of identical reproductions of cellular and extra-cellular matrix components of tissues and organs; autonomous cell assembly, which uses the principles of embryonic organ development. Here, the developing tissue manufacture their own cellular and extracellular matrix components, appropriate cell signalling and autonomous organization and patterning to yield the desired microstructure and function; and thirdly the fabrication of mini-tissue building blocks, which are the smallest structural and functional units of a tissue or an organ17. Of the three approaches, 3D bioprinting with biomimicry and carefully selected bioinks are a useful method for designing and fabricating vascularised tissues, such as the liver, bone and cartilage48,69,70. This layer-by-layer deposition of cells to precisely regulate 3D cell distribution is a major advantage when designing vascularized soft tissue, as adequate nutrient and oxygen supplies are necessary during tissue regeneration17,69,70. Hence, 3D bioprinting offers a key advantage over the traditional tissue engineering approach of seeding cells into 3D printed scaffolds48,70,71,72. The most commonly used bioprinting systems are inkjet bioprinting, micro-extrusion bioprinting, laser induced forward transfer (LIFT)17 and the key parameters in 3D bio printing tissues and organs are, maintaining cell viability and sterility during the printing process; maintaining precise cell positioning; a careful selection of bioinks; maintaining precise high resolution and mechanical strength.

The mechanical strength of bioinks, however, is typically lower than thermoplastic polymers used in acellular 3D printing. The Young’s moduli for human ribs range between 10–17 GPa’s and for cartilage, 700 kPa50. To print tissues to similar load bearing capability as native bone and cartilage, PEG-based hydrogels have been printed with compressive moduli between 300–350 kPa range, and are not strong enough45,73,74. Hence, another method used to improve mechanical strength is by adopting a hybrid approach and integrating acellular fusion deposition manufacturing (FDM) 3D printing and cellular bioprinting48,71,72. Integrating FDM 3D printing and extrusion bioprinting has made it possible to successfully fabricate a 3D printed muscle-tendon unit using two thermoplastic polymers with C2-C12 and NIH/3T3 cells72 and vascularized bone and cartilage70. By means of a CAD-CAM workstation and dedicated high throughput biological laser printing, and despite a heterogeneous requirement for bone formation, in vivo bioprinting of nano-hydroxyapatite (n-HA) has successfully been printed in the mouse calvaria defect model75.

With an integrated tissue organ printer (ITOP) and its sophisticated nozzle systems, Kang et al, have successfully fabricated stable, human-scale tissue constructs of any shape, including bone, cartilage and muscle76. The ITOP delivers various cell types and polymers in a single construct with multi-dispensing modules guided by the computer aided model and computer program, which controls the motions of the printer nozzles76. The ITOP is able to deliver cells to discrete locations in a 3D structure in liquid form. With its sophisticated nozzle systems with resolutions down to 2 μm for biomaterials and 50 μm for cells, the ITOP cross-links cell-laden hydrogels, after their passage though the nozzle system, and simultaneously prints an outer sacrificial acellular hydrogel mould, which later dissolves once the tissue construct acquires enough rigidity to retain its shape, and simultaneously creates a lattice of micro-channels permissive to nutrient and oxygen diffusion into the printed tissue constructs. These properties, all designed to work in a coordinated manner, has successfully allowed the fabrication of human scale mandible bone, ear shaped cartilage and organized skeletal muscle76. Evaluation of the characteristics and function of these tissues in vitro and in vivo showed tissue maturation and organization that may be sufficient for translation to patients76. With further studies and for the purposes of chest wall reconstruction of a surgically created large defect following chest wall resection, it may become possible to use an ITOP-like approach to fabricate structures of the chest wall and achieve an anatomical, aesthetical and functional tissue reconstruction.

Challenges and potential solutions

Limitations of bioprinting include expensive specialized equipment required for bioprinting technologies, up-scaling to good manufacturing practice standard and the added burden of regulations required to incorporate cells into biomaterial19,48. Even though 3D bioprinting is advancing at a commendable rate with new printing modalities and improved existing modalities, there still remains a multitude of technical hurdles that need to be overcome. Achieving reproducible, complex architecture that are well vascularised and suitable for clinical use76 and transitioning from current 3D printing methods to true 3D bioprinting for chest wall reconstruction has its challenges. A limited number of bioinks exist which are both bioprintable and which accurately represent the tissue architecture required to restore organ function post-printing77. While bioinks made from naturally derived hydrogels are conducive to cell growth, synthetic hydrogels are mechanically robust, and 3D printing technology like the ITOP designed to amalgamate all these aspects demonstrates success in generating bone, cartilage and muscle76. Orthotopic implantation of bioprinted bone in a calvarial bone defect model in immune-competent animals showed the formation of mature, vascularized bone tissue in implants retrieved up to 5 months76. However, host immune response to the implant, its ability to maintain function, its long-term durability and survival requires evaluation.

Building human tissues for chest wall reconstruction requires large numbers of functional, undamaged human cells and obtaining sufficient numbers of primary cells from a small tissue biopsy is feasible76. Despite advances in a more cell-friendly bioprinting process, which limit shear stress applied to the cells during the printing process and thereby minimize the detrimental effect of shear stress to cell growth or gene expression profiles, there exists a lot of unknowns for 3D stem cell culture13,17,21,76,77. The ITOP, using the two primary cell types, chondrocytes and human amniotic fluid–derived stem cells (hAFSCs) and two cell lines, fibroblasts (3T3) and myoblasts (C2C12) in mice, was able to achieve uniform, consistent placement of cells regardless of differences in the type of construct or its dimensions, and achieve cell survival and tissue formation in a small animal model76. However, the therapeutic efficacy of the implanted bone and long-term survival remains to be established as well as the efficacy of the technique in large sized bone and cartilage defects that are functionally dynamic like the chest wall. Hence, for the current technology to transition into human model further development and research is required with strict ethical and regulatory considerations.

Current regulatory regimes on cell therapy and stem cell research lack clarity when considering their application to bioprinting regulation78. Biological products in bioprinting are produced from diverse natural living sources and batch-to-batch variations resulting from complicated manufacturing processes, especially CAD-CAM in bioprinting, pose major challenges78. The legal uncertainties of bioprinting are further compounded by the multiple actors involved in the supply and production chain and all biological products have to undergo necessary evaluations to define their pharmacological and toxicological effects before clinical translation79. As variation exists in the characteristic of each biological product, specific issues may arise and safety issues include sources of biomaterials, unhealthy donors, implant efficacy, and post-implant infections79. Hence a case-by-case basis is adopted for preclinical evaluation80. Adherence to the regulatory requirements, standards and norms to secure high levels of safety and quality, and ensure maximum public protection from the developed product is often complicated by official procedures that may be burdensome and must be followed. Internationally, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) via a Biologics License Application (BLA) under the Public Health Service Act (PHSA) is in charge of the protection of public health by ensuring the safety, efficacy, and security of drugs, biological products, and medical devices79. For the UK and Europe, public debate is required on whether the existing laws might require adaptation to meet the challenges of bioprinting or whether the mass customisation that bioprinting allows will find the European Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMP) Regulation and the new Medical Device Regulation sufficient for bioprinting regulation78,79. Policymakers will also need to make an informed decision on whether to have bioprinting products and services covered by national or private health insurance78.

By overcoming the limitations of 3D bioprinting, widening the selection of available bioinks, decreasing print time, increasing print resolution, and by adhering to the strict regulatory requirements and moving more studies towards in vivo models may allow the reconstruction of chest wall tissues, ribs and cartilage in human patients.

Conclusion

The reconstruction of the chest wall, following large surgically created defects, is complex and challenging and requires a combination of pleural and skeletal reconstruction with soft tissue cover. Recent advances in 3D printing technologies and the ability to 3D print shapes with high fidelity; fabricate a scaffold tailored to the specific defect; and the ability to fabricate stable, human-scale tissue constructs of bone, cartilage and muscle, 3D bioprinting may allow the in vivo reconstruction of a large surgically created chest wall defect and facilitate in restoring its shape, structure and function with no risk of rejection. This may sound like science fiction, however, with significant research efforts into the implementation of these emerging technologies, 3D bioprinting the chest wall may well become scientifically possible.

Responses