Raptin, a sleep-induced hypothalamic hormone, suppresses appetite and obesity

Introduction

Sleep deficiency is prevalent in modern society and has become one of the major causes of metabolic diseases.1,2,3 Previous studies demonstrated that insufficient sleep increases energy intake, while its effects on energy expenditure are conflicting.4,5,6 Recent clinical research has shown that populations with sleep deprivation display a greater energy intake but with no difference in energy expenditure.7 Thus, the mechanisms by which sleep deficiency contributes to obesity deserve further study.

Sleep, a circadian behavior, is involved in body rhythms and hormonal homeostasis.8,9 The disruption of the circadian rhythm caused by sleep deficiency can disrupt the levels of appetite hormones, including ghrelin, leptin, orexins, PYY and GLP-1.10,11,12,13,14 The hypothalamus, as a critical brain region of hormone secretion, can be affected by disrupted sleep–wakefulness.15 The paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus is a vital area of the brain that synthesizes and releases hormones. The hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a circadian center, entrains rhythms into the PVN to time the daily release of hypothalamic hormones,16,17 thus playing critical roles in energy homeostasis.18 Therefore, identifying new hypothalamic hormones that are affected by circadian rhythms, including those of sleep, should provide key new insights into the treatment of obesity.

Here, we identified Raptin as a sleep-inducible hypothalamic hormone. Using several mouse models, we found that Raptin was produced in the PVN and regulated by AVP+ neurons in the SCN to exert anorexigenic effects by acting on the functional receptor glutamate metabotropic receptor 3 (GRM3) in the neurons of the PVN and stomach. We also collected and analyzed clinical data to show that patients with obesity and sleep deficiency had a negative correlation with Raptin levels while patients who underwent sleep restriction therapy (SRT) showed an increase in Raptin levels. Moreover, we found that patients with obesity carrying a heterozygous RCN2 nonsense variant had lower Raptin levels during the sleep phase and exhibited evening hyperphagia. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, Raptin represents a new rhythmic protein hormone that suppresses appetite, providing new insights into body weight control.

Results

Raptin is a sleep-induced hypothalamic hormone in mice and humans

To identify the mechanisms by which long-term sleep disturbances contribute to obesity, we utilized the previously reported sleep fragmentation (SF) mouse model that involves the disruption of continuous sleep from Zeitgeber (ZT) 0 to ZT18. Our data showed that a 2-momth SF intervention accelerated body weight gain and increased food intake (Supplementary information, Fig. S1a, b). However, we found no significant difference in energy expenditure, prompting us to focus on energy intake (Supplementary information, Fig. S1c, d).

The hypothalamus serves as a central hub for both the neuroendocrine system and the regulation of the sleep–wake cycle.9,19 Appetite-regulating hormones play a crucial role in linking energy intake to hypothalamic activity.11,20 To identify whether there were additional unknown factors contributing to SF-induced metabolic dysfunction, we performed mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of the hypothalami from control and SF mice. We found 3 downregulated and 6 upregulated factors in the hypothalami from the SF mice compared to the control mice (Fig. 1a). Among the 9 changed proteins, only three proteins (SERPINA3K, PZP, RCN2) were secreted proteins.21,22,23 SERPINA3K and PZP have both been reported to be mainly expressed in the liver, however, RCN2 was reported to be mostly expressed in the hypothalamus based on our analysis of a publicly available database. RCN2 is an endoplasmic reticulum-localized calcium-binding protein with reported roles in bone formation and cancer,22,24 which we have studied in the past.22 Thus, we selected RCN2 for our further study here.

a Volcano plots of dysregulated factors ( ≥ 1.5-fold change) identified in the hypothalamus from sleep fragmentation mice (SF) compared to age-matched controls through proteomics and MS analysis (n = 3 per group). The red circle indicates Rcn2. b UMAP plot showing the clustering of cell types in the hypothalamus by analyzing multiple public scRNA-seq data from the GSE87544, GSE119960, GSE132355, GSE132730 and GSE148568 datasets. c Dot plots displaying Rcn2 expression in different cell types of mouse hypothalamus from scRNA-seq data. d Representative image of RCN2 (green) expression in the neurons (NeuN, violet, yellow arrows indicate the colocalization), microglia (IBA1, orange, white arrows) and astrocytes (GFAP, red, white arrows) of mouse brain slices. Scale bars, 50 μm. e, f Representative images (e) and quantification of RCN2 (green, f) expression in the PVN of mice at different time points (ZT0, ZT6, ZT12, ZT18). Scale bar, 50 μm (n = 5 per group). g Representative western blot of RCN2 expression in cell lysates and the concentrated culture medium of hypothalamic GT1-7 neurons transfected with the Flag-Rcn2 plasmid. The red triangle indicates Raptin (MW: 35–55 kD), and blue triangle indicates full-length RCN2 (MW: ~55 kD). h Schematic diagram illustrating the cleavage of RCN2 into Raptin. Raptin is spanning from 28 to 249 amino acids of full-length RCN2. i Plasma Raptin levels of 3-month male mice monitored at ZT0, ZT6, ZT12 and ZT18 (the purple area indicates the sleep phase: ZT0–ZT12). j Representative images of RCN2 (green) and NeuN (red) expression in the human hypothalamus section. Scale bar, 200 μm. k Plasma Raptin levels of humans monitored at ZT0, ZT6, ZT12 and ZT18 (purple area indicates sleep phase). Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA (f, i, k). See also Supplementary information, Figs. S1, S2.

By western blot analysis, we confirmed higher RCN2 abundance in the hypothalamus compared to a range of other tissues (Supplementary information, Fig. S1e, f). To further elucidate its cellular origin in the hypothalamus, we integrated data from 5 publicly available hypothalamus single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) datasets based on mice and found that Rcn2 was predominantly expressed in neurons (Fig. 1b, c). By immunofluorescence-based microscopy, we found that RCN2 was highly expressed in the PVN rather than other nuclei of the hypothalamus or thalamus in mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S1g, h). Moreover, RCN2 was predominantly expressed in neurons (NeuN+), rather than microglia (IBA1+) or astrocytes (GFAP+), in the PVN (Fig. 1d).

We further confirmed a significantly higher RCN2 expression in the PVN during the sleep phase (ZT0 and ZT6) in contrast to the active phase (ZT12 and ZT18) (Fig. 1e, f). As the PVN is a key region for the release of hypothalamic hormones, we hypothesized that RCN2 might be a novel hypothalamic hormone. To test this hypothesis, we constructed a plasmid harboring full-length Rcn2 fused with a Flag-tag and transfected the construct into hypothalamic GT1-7 neurons. Subsequently, we identified a shorter fragment in the concentrated cell culture medium (Fig. 1g), suggesting that it might be cleaved from full-length RCN2 and then secreted. Then, we identified the amino acid sequence of this secreted protein by MS analysis and confirmed the conservation of RCN2 spaning amino acids 28–249. We named this cleaved fragment of RCN2 as “Raptin” (Fig. 1h; Supplementary information, Fig. S2a).

We next measured the daily plasma rhythms of Raptin in mice and found that its peak secretion occurred during sleep period (ZT0–ZT12) (Fig. 1i). In addition, our investigation revealed robust expression of RCN2 in PVN neurons in human hypothalamus sections and the peak of plasma Raptin aligning with the sleep period, notably at ZT18 (1 AM) (Fig. 1j, k).

To identify the enzyme that cleaves RCN2 between R249 and L250, we searched for the candidate endopeptidases that were predicted to cleave the NDGR-LDPQ sequence and identified kallikrein-related peptidase (including KLK15, 14, 1, 4) as the potential proteases responsible for RCN2 cleavage. We found that the secretion of Raptin was abrogated by aprotinin, a non-specific proprotein convertase inhibitor that acts on serine proteases, including KLKs25 (Supplementary information, Fig. S2b, c). Overexpression of KLK1 or KLK4 dramatically enhanced the level of Raptin (Supplementary information, Fig. S2d, e). Both KLK4 and KLK1 were detected in the hypothalamus and hypothalamic neurons (Supplementary information, Fig. S2f–i), and they were co-stained with RCN2 (Supplementary information, Fig. S2j, k). Of note, neither KLK1 nor KLK4 expression displayed a rhythmic change in the PVN of mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S2l–o), suggesting that the circadian variation of Raptin secretion levels is likely caused by a change in precursor expression rather than by its circadian cleavage.

Collectively, our data suggest that Raptin might be a sleep-inducible hormone both in mice and humans.

The circadian rhythm of Raptin release is controlled by SCNAVP neurons

To mark RCN2-positive neurons in the PVN, we performed stereotaxic microinjections of recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors carrying a 2.3 kb region of the Rcn2 promoter and an EGFP reporter gene (AAVs-Rcn2-Cre-EGFP) into the PVN of mice. Three weeks later, by in situ hybridization (ISH) using a Rcn2 RNA probe, we found robust co-localization of EGFP and Rcn2 mRNA, which suggested the effectiveness of the virus in labeling RCN2-positive neurons in the PVN (Supplementary information, Fig. S3a, b).

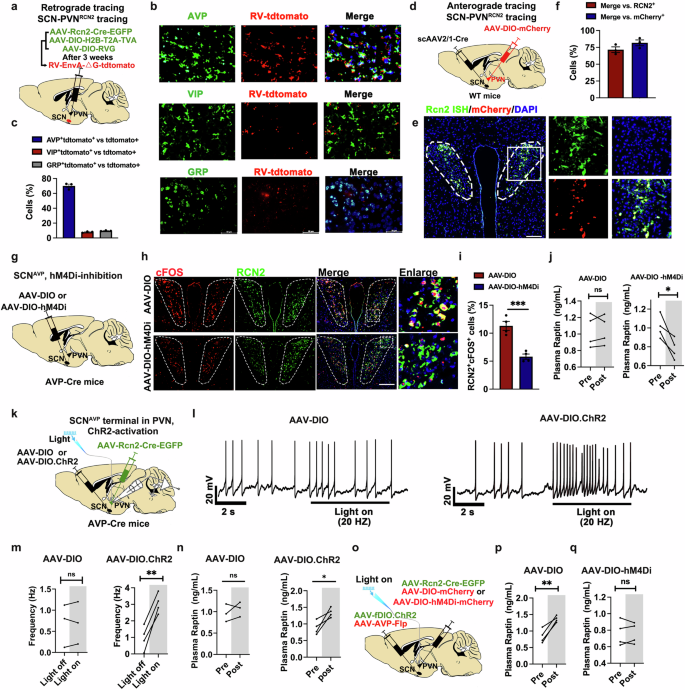

The SCN, serving as the central circadian pacemaker, exhibits a robust innervation to the PVN, orchestrating the circadian rhythm of hormone secretion from the PVN.16 The SCN mainly harbors three neuronal subtypes, including vasopressin (AVP)-, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)- and gastrin releasing peptide (GRP)-expressing neurons.26 Trans-synaptic retrograde tracing was conducted by injecting a modified rabies virus (RV-EnvA-ΔG-tdTomato), helper viruses (AAV-DIO-RVG and AAV-DIO-H2B-T2A-TVA) and PVNRCN2 labeling virus (AAV-Rcn2-Cre-EGFP) into the PVN of wild-type (WT) mice, which enabled labeling of input neurons that synapse onto PVNRCN2 neurons (Fig. 2a). Immunofluorescence staining of the SCN showed that AVP neurons were more strongly co-stained with tdTomato than the other two neuronal subtype (VIP and GRP) neurons, suggesting extensive inputs from SCN-AVP (SCNAVP) neurons to PVN-RCN2 (PVNRCN2) neurons (Fig. 2b, c). Moreover, we performed anterograde tracing by injecting the scAAV2/1-hSyn-Cre into the SCN and AAV-DIO-mCherry into the PVN of WT mice (Fig. 2d). Quantitative analysis revealed that ~72% of RCN2+ neurons in the PVN were connected to SCNAVP neurons and ~82% of mCherry-positive neurons in the PVN were RCN2+ neurons (Fig. 2e, f).

a Schematic diagram of the retrograde tracing system in SCN-innervating PVNRCN2. AAV-Rcn2-Cre-EGFP, AAV-DIO-H2B-T2A-TVA and AAV-DIO-RVG were mixed and then bilaterally injected into PVN. Three weeks later, rabies virus (RV)-EnvA-tdTomato (red) were bilaterally injected into PVN. b, c Representative images (b) and quantification (c) of colocalization with RV-tdTomato (red) by immunofluorescence staining of AVP+ neurons (top line, green), VIP+ neurons (middle line, green) and GRP+ neurons (bottom line, green) in SCN. Scale bars, 50 μm (n = 3 per group). d Schematic diagram of the anterograde tracing system in SCN-innervating PVN. The WT mice were bilaterally injected with scAAV2/1-hSyn-Cre into SCN and AAV-DIO-mCherry into PVN. e, f Representative images (e) and quantification (f) of colocalization with mCherry (red) by fluorescence ISH of Rcn2 mRNA (green) in PVN neurons. Scale bar, 50 μm (n = 3). g Schematic diagram of chemogenetic inhibition of SCNAVP neuron of Avp-Cre mice. AAV-DIO or AAV-DIO-hM4Di was injected into SCN of Avp-Cre mice. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with CNO at a dose of 2 mg/kg body weight. h, i Representative images (h) and quantification (i) of co-staining of c-Fos (red) and RCN2 (green) in PVN after CNO injection for 60 min to induce SCNAVP neuron inhibition in Avp-Cre mice. Scale bar, 50 μm (n = 4 per group). j Plasma Raptin levels of mice injected with AAV-DIO or AAV-DIO-hM4Di before and after intraperitoneal injection of CNO for 1 h (n = 4 per group). k Schematic diagram illustrating the optogenetic activation of SCNAVP neuron terminal in PVN, followed by the detection of PVNRCN2 neuron activity. AAV-DIO or AAV-DIO.ChR2 was bilaterally injected into SCN, whereas AAV-Rcn2-Cre-EGFP was injected into the PVN of Avp-Cre mice. The fiber was implanted into the PVN to stimulate SCNAVP neuronal terminal. l, m Representative traces (l) and action potential frequency (m) of PVNRCN2 neurons in brain slice before and during optogenetic activation of SCNAVP neurons (n = 3 ~ 4 per group). n The plasma Raptin levels before and after optogenetic activation of SCNAVP neurons in vivo (n = 3 ~ 4 per group). o Schematic diagram illustrating the experimental workflow for SCNAVP neuron activation and PVNRCN2 neuron inhibition. AAV-DIO-mCherry or AAV-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry with AAV-Rcn2-Cre-EGFP were injected into PVN for chemogenetic manipulation of PVNRCN2 neuron. CNO was intraperitoneally injected into mice at a dose of 2 mg/kg body weight. AAV-fDIO.ChR2 with AAV-Avp-Flp were injected into SCN for optogenetic activation of SCNAVP neurons. The fiber was implanted into the PVN to stimulate SCNAVP neuronal terminal in PVN. p, q The plasma Raptin levels in mice injected with AAV-DIO (p) or AAV-DIO-hM4Di (q) before and after CNO treatment (n = 4 per group). Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by a two-tailed paired Student’s t-test (j, m, n, p, q) or by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (i). See also Supplementary information, Figs. S3, S4.

To further determine the role of SCNAVP neurons in regulating PVNRCN2 neuron activity, we injected AAV-EF1α-DIO-GCaMp6s-EGFP and AAV-Rcn2-Cre into the PVN, while concurrently injecting control (AAV-fDIO) or excitatory (AAV-fDIO-hM3Dq) or inhibitory (AAV-fDIO-hM4Di) chemogenetic virus with AAV-AVP-Flp (for selective manipulation of AVP neurons) into the SCN (Supplementary information, Fig. S3c). The success of localized injection and the expression of the virus were confirmed by ISH and immunofluorescence staining (Supplementary information, Fig. S3d–f). The calcium activity was elevated in PVNRCN2 neurons upon clozapine-N-oxide (CNO)-induced SCNAVP neuron activation, whereas it was decreased upon SCNAVP neuron inhibition (Supplementary information, Fig. S3g, h). These findings demonstrate that SCNAVP neurons can control the activity of PVNRCN2 neurons.

To ascertain the involvement of SCNAVP neurons in regulating Raptin release in the PVN, we conducted chemogenetic manipulations by injecting control (AAV-DIO) or inhibitory (AAV-DIO-hM4Di) chemogenetic viruses into the SCN of Avp-Cre mice (Fig. 2g). Compared to the control group, the hM4Di-inhibition group showed a lower activity of SCNAVP neurons after intraperitoneal injection of 2 mg/kg CNO, as indicated by the lower colocalization of c-Fos with AVP in the SCN (Supplementary information, Fig. S3i, j). Consistent with these findings, CNO-induced inhibition of SCNAVP neurons resulted in inhibition of PVNRCN2 neurons (Fig. 2h, i). Moreover, we found that SCNAVP neuron inhibition resulted in less Raptin release (Fig. 2j) and greater food intake (Supplementary information, Fig. S3k).

We also investigated the role of SCNAVP neurons in regulating PVNRCN2 neuron activity using optogenetic technology. AAV-Rcn2-Cre-EGFP was injected into the PVN while the Cre-dependent ChR2-expressing virus (AAV-DIO-ChR2) or control virus (AAV-DIO) was injected into the SCN of Avp-Cre mice, and an optic fiber was implanted in the PVN to stimulate SCNAVP neuronal terminals (Fig. 2k). Optogenetic activation of SCNAVP neuron terminals at the PVN resulted in the activation of PVNRCN2 neurons, as reflected by enhanced firing rate of PVNRCN2 neurons (Fig. 2l, m). In line with this, the plasma Raptin levels were augmented upon optogenetic activation of SCNAVP neuronal terminals (Fig. 2n). The optogenetic activation of SCNAVP neuronal terminals also effectively lowered the amount of 1-h food intake (Supplementary information, Fig. S4a).

To further confirm that PVNRCN2 neurons affect plasma Raptin levels, we investigated whether the optogenetic stimulation-induced SCNAVP neuron activation still affected Raptin release in the PVN-specific Rcn2 deletion mice. Thus, we crossed Rcn2-floxed mice (Rcn2flox/flox mice) with Sim1-Cre mice and confirmed the effective knockout of Rcn2 in the PVN (Supplementary information, Fig. S4b–e). Next, we injected AAV-Avp-Cre-mCherry (for selective manipulation of AVP neurons) and AAV-DIO-ChR2 into the SCN of PVN-specific Rcn2 deletion mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S4f). We then confirmed the success of the localized injection and expression of the virus (Supplementary information, Fig. S4g, h). As expected, we found that the activation of SCNAVP neuron terminals in the PVN failed to increase plasma Raptin levels in PVN-specific Rcn2 deletion mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S4i). To further confirm the necessity of the PVNRCN2 neurons in this pathway, we firstly evaluated the effect of PVNRCN2 neurons on Raptin release via chemogenetic manipulation (Supplementary information, Fig. S4j). CNO-induced activation of PVNRCN2 neurons resulted in greater levels of plasma Raptin, while PVNRCN2 neuron inhibition lowered them (Supplementary information, Fig. S4k). Next, we manipulated PVNRCN2 neurons by a chemogenetic approach while activating SCNAVP neuronal terminals via optogenetic stimulation (Fig. 2o). We found an increase in the levels of plasma Raptin when only SCNAVP neurons were activated (Fig. 2p). However, the increase of plasma Raptin levels was abolished upon SCNAVP neuron activation along with PVNRCN2 neuron inhibition (Fig. 2q).

Together, our results reveal that Raptin release is controlled by a circuit from the SCNAVP neurons to the PVNRCN2 neurons.

Hypothalamus-derived Raptin suppresses food intake and prevents obesity

The results above identified Raptin as a candidate sleep-induced hypothalamic hormone. Indeed, upon SF, there was less RCN2 expression in the PVN neurons and significantly lower plasma Raptin levels in mice compared to control male mice at ZT6 (Supplementary information, Fig. S5a–c). Considering the significant effect of light on the activity of SCN neurons,27 we next determined whether RCN2 rhythmic expression within the PVN is affected by light. However, we found that the rhythmicity of Raptin secretion persisted in constant darkness but was disrupted under SF conditions (Supplementary information, Fig. S5d), indicating that its secretion is regulated by the endogenous circadian activity of SCNAVP neurons.

To test whether hypothalamus-derived Raptin is involved in SF-induced obesity, we overexpressed Rcn2 in the PVN of SF mice. We found that Raptin levels were elevated in Rcn2-overexpressing mice compared to SF male mice (Fig. 3a, b; Supplementary information, Fig. S5e–g). The overexpression of Raptin in the PVN significantly alleviated excessive weight gain and reduced food intake of SF mice to the levels seen in the control mice (Fig. 3c, d). In addition, PVN-specific Rcn2 overexpression rescued the SF-induced impairment in glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity and fat accumulation (Supplementary information, Fig. S5h–l).

a Schematic diagram of Rcn2 overexpression in PVN of mice with SF intervention. AAV-hSyn-Ctrl or AAV-hSyn-Rcn2 was bilaterally injected into the PVN of WT male mice, followed by SF intervention for 9 weeks. b The plasma Raptin levels of 4-month male control or SF mice injected with AAV-hSyn-Rcn2 or AAV-hSyn-Ctrl (n = 5 per group). c, d Body weight (c) and cumulative food intake (d) of 4-month male control mice, SF mice and SF mice with Rcn2 overexpression. ###P < 0.001 when control mice were compared to SF mice. ***P < 0.001 when SF mice were compared to SF mice with Rcn2 overexpression (n = 5 per group). e Schematic diagram illustrating the 4-week ICV infusion of Raptin (40 ng/h/g body weight) or PBS in 4-month SF male mice. f, g Body weight change (f) and cumulative food intake (g) of 4-month SF male mice with ICV infusion of Raptin or PBS for 4 weeks (n = 4 per group). h, i Body weight (h) and cumulative food intake (i) of 2-month Rcn2flox/flox and Sim1Cre;Rcn2flox/flox male mice fed an HFD for 9 weeks (n = 6 per group). j Schematic diagram of 2-month Sim1Cre;Rcn2flox/flox mice or Rcn2flox/flox male mice with 8-week HFD and 4-week ICV infusion of Raptin (40 ng/h/g body weight) or PBS. k, l Body weight (k) and cumulative food intake (l) of Rcn2flox/flox and Sim1Cre;Rcn2flox/flox male mice with ICV infusion of PBS or Raptin (n = 6 per group). ***P < 0.001 when Rcn2flox/flox mice were compared to Sim1Cre;Rcn2flox/flox mice. ###P < 0.001 when Sim1Cre;Rcn2flox/flox mice were compared to SimCre;Rcn2flox/flox mice treated with Raptin. m Representative H&E staining of eWAT and iWAT of 4-month control mice or SimCre;Rcn2flox/flox male mice with ICV infusion of PBS or Raptin. Scale bar, 100 μm (n = 6 per group). Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***/###P < 0.001 by two-way ANOVA (b–d, f–i, k, l). See also Supplementary information, Figs. S5–S7.

To further validate the metabolic benefits of Raptin, we generated and purified recombinant mouse Raptin protein with a His-tag, whose validity was confirmed by silver staining (Supplementary information, Fig. S6a). We selected the dose of Raptin (40 ng/h/g body weight) for intracerebroventricular (ICV) infusion based on its elevated range in plasma during the sleep phase (Supplementary information, Fig. S6b). Moreover, either the ICV infusion of Raptin or intraperitoneal injection of Raptin had suppressive effects on appetite and gastric emptying (Supplementary information, Fig. S6c, d). Next, we performed ICV infusion of Raptin for 4 weeks in SF male mice to explore the effect of Raptin on SF-induced metabolic dysfunction (Fig. 3e). The sustained supplementation of Raptin successfully rescued the metabolic disturbance in SF mice, as indicated by less food intake and weight gain compared to vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 3f, g).

Previous studies revealed that high-fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity impairs the sleep–wake cycle.28 Consistent with those findings, we found that HFD-induced obese male mice exhibited more wake time and less non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep time than normal diet (ND)-fed mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S6e). Moreover, we found that HFD-induced obese mice had lower plasma Raptin levels than ND-fed mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S6f). Therefore, we applied ICV infusion of Raptin into HFD-induced obese male mice. Raptin treatment resulted in weight loss and appetite suppression in WT mice fed an HFD (Supplementary information, Fig. S6g–i). Pair feeding (caloric matching) of PBS-treated mice showed a similar body weight gain to Raptin-treated mice, indicating that the reduction in food intake is a major factor by which Raptin induces weight loss (Supplementary information, Fig. S6g–i).

To further verify that the appetite inhibition was mediated by direct effects in PVN but not the arcuate nucleus (ARC), we incubated brain slices from Cas9-EGFP[KI/+];Pomc-Cre male mice and Cas9-EGFP[KI/+];AgRP-Cre male mice with Raptin. Then, we detected the activity of POMC+ neurons and AgRP+ neurons (canonical neurons for appetite control in ARC)29 before and after Raptin treatment. The results indicated that Raptin failed to activate either the POMC+ neurons or the AgRP+ neurons (Supplementary information, Fig. S6j–m). Collectively, our results raised the possibility that Raptin has a prophylactic effect on obesity.

We then assessed the metabolic effects in PVN-specific Rcn2 deletion male mice. Rcn2 deficiency in the PVN resulted in significantly decreased Raptin level, especially in the sleep phase (Supplementary information, Fig. S7a). Rcn2 deficiency in the PVN did not impair the sleep–wakefulness cycle as indicated by a nonsignificant change of wakefulness, NREM sleep duration and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep duration (Supplementary information, Fig. S7b). However, there was a slight increase in body weight in the PVN-specific Rcn2 knockout male mice even during ND feeding (Supplementary information, Fig. S7c). When fed a HFD, PVN-specific Rcn2 knockout mice showed a greater increase in body weight compared to littermate control mice (Fig. 3h). Compared to Rcn2flox/flox mice fed an HFD, PVN-specific Rcn2 knockout mice showed a greater increase in food intake both during the light phase or the night phase (Fig. 3i; Supplementary information, Fig. S7d). Additionally, PVN-specific Rcn2 knockout male mice showed decreased oxygen consumption and energy expenditure during the dark period even though they were not changed in the day period or total period (Supplementary information, Fig. S7e–h). Importantly, no alterations of feeding-related hormones were detected in the PVN-specific Rcn2 knockout male mic (Supplementary information, Fig. S7i–m). Moreover, there was no difference in the activity of POMC+ and AgRP+ neurons (Supplementary information, Fig. S7n–q), further indicating that RCN2 did not influence these canonical appetite-regulatory pathways.

To further confirm the effect of Raptin on body weight loss and appetite suppression, we performed a rescue experiment by ICV infusion of Raptin in PVN-specific Rcn2-deficient male mice (Fig. 3j). Sustained Raptin release effectively delayed the rapid weight gain caused by Rcn2 deficiency and lowered food intake to the levels of Rcn2flox/flox mice (Fig. 3k, l). By histological staining, we found that fat accumulation in epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) and inguinal white adipose tissue (iWAT) of the knockout mice was abolished by treatment with Raptin (Fig. 3m). In addition, Raptin rescued the impaired glucose homeostasis of the Rcn2-deficient mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S7r–u). Moreover, Raptin showed no effects on leptin and orexin A levels (Supplementary information, Fig. S7v, w) and did not influence the physical activity of mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S7x).

Together, these findings suggest that hypothalamus-derived Raptin inhibits food intake and prevents obesity.

Raptin binds to GRM3 in neurons of the PVN and stomach to suppress food intake

To identify the receptor for Raptin, we performed MS analysis using cell lysate extracted from hypothalamic GT1-7 neurons incubated with His-labeled Raptin. This approach did not enrich our previously identified receptor complex (neuropilin-2 and integrin beta-1) from the bone marrow adipose tissues.22 However, we identified GRM3 as a new receptor of Raptin, and chose it for further evaluation because of its highest score and coverage among identified canonical receptors (Fig. 4a, b). The binding between Raptin and GRM3 was confirmed via saturation binding assay (Fig. 4c).

a List of candidate membrane receptors of Raptin through MS analysis. The cell lysate of hypothalamic neurons was incubated with His-Raptin. The proteins pulled down by anti-His antibody were tested by MS analysis. b Representative mass spectrogram of GRM3 (The identified sequence of GRM3 peptide fragment: VGHWAETLYLDVDSIHWSR). c Effect of Raptin on GRM3 binding in HEK293T cells transfected either with control plasmid or Grm3 plasmid. d Representative western blot of GRM3 expression in different tissues. e Representative images of GRM3 expression (red) in the PVN and muscular layer of the stomach. Scale bars, 50 μm. f Binding assay on frozen tissue sections of PVN from Grm3flox/flox or Sim1Cre;Grm3flox/flox mice. His-Raptin or PBS was pre-incubated with frozen tissue slices. Scale bar, 50 μm. g Binding assay on frozen tissue sections of the stomach from Grm3flox/flox mice intragastrically injected with AAV-Ctrl or AAV-Nos1-Cre. His-Raptin or PBS was pre-incubated with frozen tissue slices. Scale bar, 50 μm. h, i Body weight (h) and 24-h food intake (i) of 4-month control (Grm3flo/flox mice) and PVN-specific Grm3-deficient male mice (Sim1Cre;Grm3flox/flox mice) with 10-week HFD (n = 5 per group). j Schematic diagram illustrating the injection of AAV-Nos1-Cre into the muscle layer of the stomach of 2-month Grm3flox/flox male mice to generate stomach-specific Grm3-deficient mice. Control male mice are Grm3flox/flox mice. k, l Body weight (k) and food intake (l) of 4-month control or stomach-specific Grm3-deficient male mice (n = 5 per group). m Gastric emptying of 4-month control or stomach-specific Grm3-deficient male mice measured via phenol red test (n = 5 per group). n Gastric emptying of 4-month control or stomach-specific Grm3-deficient male mice measured via acetaminophen absorption test (n = 5 per group). o–q Body weight (o), food intake (p) and gastric emptying (q) of 4-month controls (Grm3flox/flox mice) and dual tissue-specific Grm3-deficient male mice (Sim1Cre;Grm3flox/flox mice with injection of AAV-Nos1-Cre into stomach) with or without treatment of Raptin. Mice were fed an HFD. Raptin was injected into mice via the tail vein at a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight every other day for 8 weeks (n = 5 per group). r H&E staining of the eWAT and iWAT of the control and dual tissue-specific Grm3-deficient male mice treated with PBS or Raptin. Scale bar, 100 μm (n = 5 per group). Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by two-way ANOVA (h, k, n, o–q) or by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (i, l, m). See also Supplementary information, Figs. S8, S9.

It has been reported that GRM3 is composed of an extracellular venus flytrap domain (VFT), a transmembrane domain (TMD) consisting of seven TM helices, and a cysteine-rich domain (CRD) connecting VFT and TMD.30 Therefore, we performed a molecular dynamics clustering analysis between GRM3 VFT and RCN2 and found a representative conformation with their binding detail. The GRM3 residues binding to RCN2 included Asn495, Ser479, Lys477, Arg59 and Gln360 (Supplementary information, Fig. S8a). In line with these results, we verified that Raptin bound to the VFT of GRM3 in GT1-7 cells through immunoprecipitation assay (Supplementary information, Fig. S8b). Moreover, immunoprecipitation assay and specific binding assay further showed that the mutation at N495 of GRM3 disrupted its binding to Raptin, suggesting that Asn495 is the key residue for this interaction (Supplementary information, Fig. S8c, d).

We next found that GRM3 was highly expressed in the hypothalamus and stomach (Fig. 4d, e). To further confirm the target tissue of Raptin, we performed binding assays on frozen tissue sections by incubating purified His-Raptin with different tissues. The results revealed that Raptin targeted GRM3 in the PVN and the muscular layer of the stomach (Fig. 4f, g; Supplementary information, Fig. S8e, f). In the PVN, like RCN2, GRM3 was mostly expressed in neurons, rather than in astrocytes or microglia (Supplementary information, Fig. S8g, h). However, the immunofluorescence colocalization between RCN2 and GRM3 was weak (Supplementary information, Fig. S8i), raising the possibility that Raptin functions via a paracrine manner. Therefore, we generated PVN-specific Grm3 knockout mice (SimCre;Grm3flox/flox mice) and verified the successful deletion of Grm3 in the PVN (Supplementary information, Fig. S9a, b). We observed that Raptin displayed strong binding signals in the PVN, while the binding signals disappeared in the Grm3-deficient PVN (Fig. 4f).

The neurons innervating the gastrointestinal (GI) muscles are mainly CHAT-positive and NOS1-positive neurons.31,32 Thus, we performed co-staining of GRM3 with CHAT or NOS1 in the stomach and found that GRM3 was colocalized with NOS1-positive neurons (Supplementary information, Fig. S9c). Next, we generated a gastric NOS1-positive neuron-specific Grm3 knockout mice by injecting AAV-Nos1-Cre virus into the muscular layer of the stomach in Grm3flox/flox male mice. Consistent with the binding signals in the PVN, we confirmed that Raptin exhibited strong binding signals in the stomach of control male mice, while the binding signal disappeared in Grm3-deficient stomach neurons (Fig. 4g).

Next, we examined the phenotypes of Grm3-deficient mice. No obvious changes of wakefulness, NREM sleep duration and REM sleep duration were observed between control littermates and PVN-specific Grm3-deficient male mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S9d). However, the faster weight gain in Sim1Cre;Grm3flox/flox male mice was observed under ND feeding (Supplementary information, Fig. S9e). With an HFD feeding, Sim1Cre;Grm3flox/flox male mice exhibited greater body weight gain compared to control male littermates (Fig. 4h). Consistent with these findings, PVN-specific Grm3 knockout mice showed a greater increase in food intake compared to littermate control mice both during the light phase and night phase (Fig. 4i; Supplementary information, Fig. S9f). Moreover, the body weight and food intake were also greater in the stomach-specific Grm3-deficient mice compared to the Grm3flox/flox mice (Fig. 4j–l). As GI motility is important for appetite and weight control,33 we measured gastric motility and found that Grm3 deletion resulted in accelerated gastric emptying (Fig. 4m, n). To further explore the effects of GRM3 in the PVN and stomach, we injected AAV-Nos1-Cre virus into the stomach of Sim1Cre;Grm3flox/flox male mice to obtain mice with Grm3 knockout both in the PVN and stomach (dual tissue-specific Grm3 knockout mice). Grm3flox/flox mice injected with the control virus were used as controls. The dual tissue-specific Grm3-deficient mice showed a higher body weight and food intake compared to either single PVN-specific Grm3-deficient male mice or single stomach-specific Grm3-deficient male mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S9g, h).

To further confirm the effects of Raptin mediated by GRM3, we administered recombinant Raptin in the dual tissue-specific Grm3-deficient male mice. We found that Raptin decreased body weight, gastric emptying, food intake and fat accumulation in control Grm3flox/flox male mice fed a HFD (Fig. 4o–r). However, the Raptin-mediated effects were blocked in the dual tissue-specific Grm3-deficient male mice, which exhibited no change in body weight, gastric emptying, food intake and fat accumulation when treated with Raptin (Fig. 4o–r). Regarding metabolic alterations, Raptin-induced improvements of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity were blocked in the dual tissue-specific Grm3-deficient male mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S9i–l). Of note, Raptin administration decreased body weight and food intake in control female mice fed an HFD, but not in the dual tissue-specific Grm3-deficient female mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S9m, n). Furthermore, Rcn2 overexpression in the PVN of mice inhibited appetite, gastric emptying and decreased body weight, which were weakened in stomach-specific Grm3-deficient mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S9o–q).

Together, these results suggest that PVN-derived Raptin inhibits appetite and gastric emptying by binding GRM3 in the neurons of the PVN and the stomach, which ultimately leads to a reduction in body weight.

Raptin-GRM3 signaling maintains the energy supply for neuron activation and anorexigenic effects

Next, we investigated whether Raptin signaling directly affects neuronal activity in a GRM3-dependent manner. To determine that GRM3-positive neurons in the PVN (PVNGRM3 neurons) play critical roles in appetite control, we firstly constructed AAVs carrying a 2.3 kb region of the Grm3 promoter and an EGFP reporter gene (AAVs-Grm3-Flp-EGFP). By ISH utilizing a Grm3 RNA probe, we verified the effectiveness of these viruses in marking the GRM3-positive neurons in the PVN (Supplementary information, Fig. S10a, b).

PVNGRM3 neurons help better define the effect of Raptin on GRM3 signaling. Therefore, we injected AAV-Grm3-Flp-EGFP into the PVN of Grm3flox/flox and Sim1Cre;Grm3flox/flox mice to label PVNGRM3 neurons. By patch-clamp electrophysiology analysis in vitro, we found that EGFP-labeled PVNGRM3 neurons were activated in the presence of Raptin (1 ng/mL; in control artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF)) in the brain slice of Grm3flox/flox mice, but not in Sim1Cre;Grm3flox/flox mice (Fig. 5a–c). Similarly, c-Fos staining revealed that Raptin could activate NOS1+ neurons in the stomach, while Grm3 deficiency abolished this effect of Raptin (Fig. 5d).

a Schematic diagram illustrating the injection of AAV-Grm3-Flp-EGFP into PVN of control and PVN-specific Grm3-deficient male mice to label PVNGRM3 neurons, followed by neuronal activity recording of PVNGRM3 neurons in brain slice before and during Raptin treatment. Raptin was dissolved in ACSF at a concentration of 1 ng/mL and incubated with brain slices for 10 min. b, c Representative traces (b) and action potential frequency (c) of PVNGRM3 neurons from control and PVN-specific Grm3-deficient male mice (n = 5 per group). d Representative images of c-Fos (green) in the GRM3+ neurons of the stomach from control and stomach-specific Grm3-deficient male mice followed by administration of Raptin via tail vein at a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight for 1 h. Scale bar, 50 μm. e Representative images of labeled mitochondria (cyan) and KHC (red) in primary hypothalamus neurons transfected with control or Grm3 siRNA, followed by treatment of Raptin or PBS. These neurons were transfected with Mito-BFP and Khc-RFP plasmids to label mitochondria and KHC protein, respectively. Scale bar, 5 μm. f Quantification of the fluorescent KHC present on mitochondria, defined by the intensity of KHC in the region overlapping Mito-BFP (n = 4 per group). g KEGG analysis of changed phosphorylation in the hypothalamic GT1-7 neurons through global quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis. Hypothalamic GT1-7 neurons were treated with PBS or Raptin at 10 ng/mL for 1 h. h Representative western blot of AKT signaling in cell lysates and KHC expression in mitochondria enriched from primary neurons treated with Raptin or Grm3 siRNA. Raptin was used at 10 ng/mL for 1 h. CYTO1 was used as the internal control of mitochondria. i Representative western blot of AKT signaling in cell lysates and KHC expression in mitochondria enriched from primary neurons treated with Raptin or PI3K-AKT pathway inhibitors (Wortmannin and LY294002). CYTO1 was used as the internal control of mitochondria. j, k Representative images (j) and quantification (k) of the fluorescent KHC (red) present on mitochondria, defined by the intensity of KHC in the region overlapping Mito-BFP (cyan) in primary hypothalamus neurons. Scale bar, 5 μm (n = 4 per group). l, m Schematic diagram illustrating the injection of AAV-hSyn-Ctrl or AAV-hSyn-shKhc in the PVN of 2-month WT male mice to generate the control and PVN-specific Khc knockdown mice, followed by treatment of PBS or Raptin. Representative immunofluorescence images (l) and quantification (m) of c-Fos (red) expression in PVN. Scale bar, 50 μm. n 24-h food intake of the PVN-specific Khc knockdown mice and control mice with or without treatment of Raptin (n = 4 per group). Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***/###P < 0.001 by a two-tailed paired Student’s t-test (c) or by two-way ANOVA (f, k, m, n). See also Supplementary information, Figs. S10–S12.

To determine that PVNGRM3 neurons played critical roles in appetite control, we manipulated PVNGRM3 neurons by injecting an excitatory chemogenetic virus (AAV-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry) and AAV-Grm3-Cre into the PVN (Supplementary information, Fig. S10c). The AAV-Grm3-Cre-EGFP to mark the GRM3-positive neurons in the PVN was confirmed by ISH (Supplementary information, Fig. S10d, e). By this approach, we found an inhibition of appetite along with no change of gastric emptying upon activation of GRM3+ neurons in the PVN after intraperitoneal injection of 2 mg/kg CNO (Supplementary information, Fig. S10f, g), suggesting that the PVN pathway was not directly communicating with the stomach. However, the CNO-induced activation of GRM3+ neurons in the stomach resulted in appetite suppression along with reduced gastric emptying (Supplementary information, Fig. S10h–l).

To elucidate the mechanism of neuronal activation, we conducted a global quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of hypothalamic neurons treated with Raptin or PBS. By COG analysis of the differentially phosphorylated proteins, we found obvious alterations of transport and catabolism, as well as cell motility (Supplementary information, Fig. S11a). Considering that mitochondrial movement is critical for energy distribution to sustain neuron activity,34 we sought to investigate whether mitochondrial motility was involved in the energy supply of Raptin-stimulated neuron activation. Kinesin heavy chain (KHC) serves as a primary anterograde motor for the axonal transport of mitochondria and governs aspects of mitochondrial distribution in neurons, and the localization of KHC in the mitochondria suggests the increased mitochondrial movement.35 Therefore, we transfected primary hypothalamic neurons with mito-BFP and Khc-RFP plasmids. We observed that Raptin treatment increased the colocalization of KHC and mitochondria, while this effect was abolished in Grm3-deficient neurons (Fig. 5e, f).

To identify the signaling pathway involved in mitochondrial movement, we conducted a KEGG analysis using phosphoproteomic data. Among the top 10 pathways, the PI3K-AKT pathway was remarkably impacted by Raptin (Fig. 5g). To assess the intrinsic potency of Raptin in vitro, GT1-7 cells expressing GRM3 were used to measure p-AKT accumulation as the downstream signaling of receptor activation (Raptin 50% effective concentration [EC50] = 0.31 ng/mL) (Supplementary information, Fig. S11b). We then verified that Raptin activated PI3K-AKT signaling in control neurons but not in neurons with siRNA-mediated knockdown of Grm3 (Fig. 5h). Previous studies revealed that the primary motor complex, formed by KHC binding to MIRO1, regulated mitochondrial transport.35,36 KHC detection in the mitochondrial fraction reflected the mitochondrial mobility.37 Thus, we examined the levels of KHC heavy chain in the mitochondrial fraction and found that their levels were increased by Raptin treatment in control neurons but not in the Grm3 knockdown neurons (Fig. 5h). Moreover, treatment with Wortmannin and LY294002 (PI3K inhibitors) effectively abolished the Raptin-induced increase of KHC associated with mitochondria (Fig. 5i).

Considering that axonal mitochondria serve as local power stations for ATP supply to sustain prolonged neural activity, we performed live imaging experiments to detect ATP levels in mitochondria in hypothalamic neurons. ATP levels were assessed using genetically encoded Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based ATP probe pCMV-AT1.03.38 The relative intensity ratio of pCMV-AT1.03 YFP (ATP-bound) to CFP (ATP-free) reflected the ATP levels. We found that Raptin treatment resulted in greater ATP levels in mitochondria of control neurons but not in Grm3-deficient neurons (Supplementary information, Fig. S11c, d). Consistently, Wortmannin treatment abolished the Raptin-induced distribution of KHC in mitochondria (Fig. 5j, k) and increase of mitochondrial ATP levels (Supplementary information, Fig. S11e, f). Thus, these findings suggested that Raptin promoted GRM3+ neuron activity via PI3K-AKT signaling.

Previous studies showed that glutamate, as a classical endogenous ligand of GRM3, can affect neuronal activity through inhibiting cyclic AMP (cAMP) signaling.39 Hence, we compared the difference between glutamate and Raptin regarding the downstream signaling. Time-resolved FRET (trFRET) measurements showed the affinity between GRM3 and Raptin or glutamate in HEK293 cells (Supplementary information, Fig. S12a). However, glutamate inhibited cAMP signaling but did not affect AKT signaling, whereas Raptin promoted AKT signaling but did not affect cAMP signaling (Supplementary information, Fig. S12b–d). In addition, we treated GT1-7 cells with Raptin and GRM3 receptor agonists (LY354740, LY2794193 and LY379268), inhibitors (LY341495) or allosteric agents (VU0650786), respectively. We found that none of the GRM3 receptor agonists, inhibitors or allosteric agents could alter Raptin-GRM3-mediated AKT signaling (Supplementary information, Fig. S12e, f). Together, glutamate and Raptin did not show mutual effects on the downstream AKT signaling.

To further explore whether KHC was indispensable in GRM3-mediated neuronal activation and appetite control, we injected Raptin or PBS into mice with or without knockdown of Khc in the PVN (Fig. 5l). The knockdown efficiency was confirmed in isolated PVN region (Supplementary information, Fig. S12g). We found that Raptin treatment activated neurons in the PVN, however, this effect was impaired by the knockdown of Khc (Fig. 5l, m). Moreover, the effect of Raptin on appetite inhibition was also diminished in PVN-specific Khc knockdown mice (Fig. 5n). We found that LY354740 treatment in the PVN did not affect appetite in either control mice or PVN-specific Khc-deficient mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S12h, i). In addition, LY354740 treatment did not affect food intake or gastric emptying in either control mice or stomach-specific Khc-deficient mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S12j–l). Furthermore, we chemogenetically manipulated PVNGRM3 neurons with or without knockdown of Khc in the PVN (Supplementary information, Fig. S12m). Intriguingly, CNO-induced excitatory stimulation suppressed food intake in control mice, but this effect was attenuated in the PVN-specific Khc knockdown mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S12n). CNO-induced excitatory stimulation showed a similar trend in terms of effect on food intake, along with altered gastric emptying, in the mice with Khc knockdown in the stomach (Supplementary information, Fig. S12o–q).

In conclusion, we propose that Raptin-Grm3 signaling promotes the PI3K-AKT pathway, playing a crucial role in the KHC-mediated energy supply for neuron activation and appetite control.

Raptin dysregulation is involved in sleep deficiency-induced obesity in humans

Regarding clinical relevance, we sought to investigate the effects of sleep quality on the risk of obesity in humans. Therefore, we analyzed the interplay among sleep quality, Raptin release and obesity within a cohort of 262 participants that were matched for age and sex. Among these participants, 127 presented with obesity (BMI: 32.30 ± 3.00), while the remaining 135 were not obese (BMI: 22.0 ± 2.4) (Fig. 6a). Comparative analysis demonstrated that individuals with obesity exhibited lower sleep quality as indicated by reduced total sleep time (TST) and sleep efficiency (SE) along with elevated wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO) and sleep latency (SL), in contrast to their non-obese counterparts (Fig. 6b; Supplementary information, Fig. S13a–c). Moreover, participants with obesity showed significantly lower plasma Raptin levels (Fig. 6c).

a Schematic diagram of the cross-sectional study evaluating the effect of sleep on obesity. b, c Violin plot of sleep efficiency (b) and plasma Raptin levels (c) in participants with or without obesity (n = 127 for obese group, n = 135 for non-obese group). d Spearman’s correlation between SE and BMI in participants with obesity (n = 127 for obese group). e Spearman’s correlation between SE and Raptin levels in participants with obesity (n = 127 for obese group). f Spearman’s correlation between Raptin levels and BMI in participants with obesity (n = 127 for obese group). g Schematic diagram illustrating the workflow of a prospective study evaluating the effect of SRT on obesity (n = 15 per group). h–k Change of SE (h), body weight (i), cumulative energy intake (j) and plasma Raptin level (k) between control and SRT groups. l Spearman’s correlation between SE change and plasma Raptin level change in participants with obesity. The triangle represents the control group, and the circle represents the SRT group. m, n Spearman’s correlation between plasma Raptin level change and changes of body weight (m) and energy intake (n) in participants with obesity. The triangle represents the control group, and the circle represents the SRT group. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM or β estimate ± 95% CI. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by Mann–Whitney U test (b, c), Spearman’s correlation analysis (d–f, l–n) or a two-tailed paired Student’s t-test (h–k). The P values of Spearman correlation analysis were corrected by Bonferroni method. See also Supplementary information, Fig. S13.

We further conducted a detailed examination of these correlations by analyzing the non-obese or obese group independently. In the non-obese population, we did not observe obvious correlations between BMI and SE (Supplementary information, Fig. S13d). Moreover, Raptin levels showed no significant correlation with BMI and sleep quality indicators including TST, SE, WASO and SL (Supplementary information, Fig. S13e–i). However, in the population with obesity, we observed a negative correlation between SE and BMI (Fig. 6d). Except for TST, other sleep quality indicators (SE, SL and WASO) were correlated with Raptin levels in the population with obesity (Fig. 6e; Supplementary information, Fig. S13j–l). Consistently, we observed an obvious negative correlation of BMI with Raptin levels in the population with obesity (Fig. 6f). These intricate associations indicated a nuanced relationship between sleep quality, Raptin release, and obesity. Collectively, these results suggest that sleep deficiency may disrupt Raptin release, particularly in cases of obesity.

Given the established association between disturbed sleep quality and development of obesity, we explored whether improved sleep quality in patients with obesity and insomnia could promote Raptin release and inhibit food intake. SRT,40,41 a recognized treatment for long-term insomnia in clinical settings, was employed for this investigation. We conducted a prospective cohort study by recruiting male patients with obesity and insomnia. The participants were divided into a control group without any intervention (n = 15) and an intervention group treated with 3-month SRT regimen (n = 15) (Fig. 6g). The age and BMI of the control group (age: 31.7 ± 5.1, BMI: 30.0 ± 1.2) and SRT group (age: 32.1 ± 5.9, BMI: 30.4 ± 2.1) were matched. As expected, patients undergoing SRT exhibited substantial improvements in SE (Fig. 6h), a reduction in body weight and energy intake (Fig. 6i, j), as well as an increase in plasma Raptin levels (Fig. 6k). Moreover, the change of Raptin levels displayed a positive correlation with indicators of improved SE (Fig. 6l), and negative correlations with reduction of body weight and energy intake (Fig. 6m, n). These data suggest a deep connection among sleep patterns, plasma Raptin levels and obesity in humans.

A RCN2 nonsense mutation contributes to night-eating syndrome

To further investigate the genetic evidence linking RCN2 to obesity, we conducted Sanger sequencing to screen for RCN2 variants in 2000 Chinese participants with obesity. Notably, we identified a heterozygous RCN2 nonsense variant that co-segregated with obesity within a specific family, as indicated by this RCN2 variant observed in the proband with obesity (II2) and two other family members with obesity (II3 and III2) but not in other family members (Fig. 7a, b). This variant, c.469 C > T, in RCN2 was predicted to result in the substitution to a premature termination codon at site Arg157 within the exon 4 of RCN2 (p.Arg157Ter) (Fig. 7c). Moreover, the neighboring region of this mutation is highly conserved among vertebrates (Fig. 7c). To verify the loss of functionality of this RCN2 variant, we overexpressed the human WT RCN2 and this RCN2 variant in HEK293T cells. By western blotting, we found a Raptin fragment with small molecular weights in cell lysate but not in concentrated culture medium (Supplementary information, Fig. S13m), suggesting that the Raptin fragment could not be secreted to bind GRM3 to exert the downstream effects. The co-immunoprecipitation assay showed no His-tagged RCN2 binding to GRM3 VFT in the cells transfected with this RCN2 variant (Supplementary information, Fig. S13m). Moreover, the conditioned medium from hypothalamic neurons overexpressing WT RCN2 promoted downstream AKT signaling, but this effect disappeared in neurons expressing the mutant RCN2 (Supplementary information, Fig. S13n).

a Pedigree of the family with NES. The red arrow indicates the proband in this family. WT RCN2 genotypes are depicted as +/+, and heterozygous RCN2 genotypes are depicted as +/–. Numbers in red brackets indicate the BMIs of three affected obese patients. b Sanger sequencing chromatograms from II2, II3, III2 and one representative family member (II5). The c.469 C > T transition is indicated by the red arrow. c Protein homology of the neighboring region of the variant among selected species. The arrow shows the location of the p.Arg157Ter substitution. The red amino acid residue indicates the altered residue by the above variant found in this family. d–f Plasma Raptin levels of NES patients (II2, d; II3, e; III2, f) and their respective obese control (age-, sex- and BMI-matched, n = 6) during night phase. g, h The cumulative energy intake curves (g) and quantification (h) of II2 and his obese control (age-, sex- and BMI-matched, n = 6) during day and night phases. i, j The cumulative energy intake curves (i) and quantification (j) of II3 and her obese control (age-, sex- and BMI-matched, n = 6) during day and night phases. k, l The cumulative energy intake curves (k) and quantification (l) of III2 and his obese control (age-, sex- and BMI-matched, n = 6) during day and night phases. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. See also Supplementary information, Fig. S13.

Notably, all three patients with obesity carrying this variant suffered from night-eating syndrome (NES), characterized by nocturnal awakenings for food intake in a fully conscious state, as reported in the questionnaires. This variant was associated with an increase in BMI, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), and body fat in patients with NES within this family (Supplementary information, Fig. S13o). Additionally, their serum triglycerides were elevated compared to the unaffected controls (Supplementary information, Fig. S13o).

Individuals with NES showed lower plasma Raptin levels compared to other family members (Supplementary information, Fig. S13o). Compared to age- and BMI-matched participants with obesity, the three patients with NES showed lower plasma Raptin levels during the night sleep phase (Fig. 7d–f). To assess food intake, we monitored the total calorie intake within a 24-h period and observed a specific increase in nocturnal food intake in the patients with NES (II2, II3 and III2) compared to their sex-, age- and BMI-matched participants during the night, respectively (Fig. 7g–l). These results suggest that impaired Raptin release might be an important contributor to NES in this family.

Discussion

The history of endocrinology is the history of hormone discovery and their functional evaluation.42,43,44 The hypothalamus, as a central hub of the neuroendocrine system and interoception, can secrete hormones in response to metabolic signals, thus playing crucial roles in energy balance.45,46 For decades, scientists have been dedicated to identifying new hypothalamic hormones, with the aim to elucidate the central and peripheral networks that underlie the neuroendocrine system as a way to identify new approaches for the treatment of obesity.46,47 By doing so, the genetic basis of rare forms of hereditary obesity has been identified, key drivers of more common cases of obesity, such as leptin resistance, have come into focus, and new ideas for successfully targeting obesity, including GLP1 receptor agonism, have been confirmed. But even so, the identification of new hypothalamic hormones that regulate food intake and thus adiposity is still of keen interest. Here, we identified a sleep-induced hypothalamic hormone that plays a role in promoting anorexigenic effects through GRM3-dependent signaling.

Poor sleep habits contributed to overeating and obesity, which is associated with dysrhythmic release of hormones.2,48,49,50 The idea in the field behind this is that disruptions in the circadian rhythm lead to overeating in the wrong phase of the day.5,51 Here, we identified the rhythmic hormone Raptin, which we found peaks during sleep but is depleted by disrupted sleep, as one that maintains the low desire for energy intake during the sleep phase. Thus, our results offer new insights into how the disrupted circadian rhythm leads to an increase in appetite.

The circadian network regulates the release of hormones, which can affect the behavioral circadian rhythm in turn, such as eating, sleeping, locomotion and so forth.52,53 Here, we showed that the circadian release of hypothalamic Raptin decreases appetite but does not affect other important circadian behaviors, including the sleep cycle itself or physical activity. Therefore, further studies are still needed to elucidate whether Raptin derived from other locations affects unappreciated circadian behaviors or physiological processes during homeostasis or other specific states.

Consistent with the reported mechanism of canonical appetite hormones, including leptin and GLP1,11,20,54,55 Raptin acted locally and distally via binding to its specific receptor in the neurons of the PVN and the stomach, respectively, thereby suppressing appetite and ameliorating weight gain. Thus, another interesting observation of this study is that we identified GRM3 as the receptor of Raptin to regulate gastric emptying and appetite. GRM3 is a member of the group II of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) of glutamate, which is widely expressed in the central nervous system.56 Ligand binding to GRM3 can cause inhibition of adenylyl cyclase cascade.56 Moreover, glutamate signaling in specific regions has been reported to promote appetite.57 Different from these findings, we identified Raptin as a novel ligand of GRM3 to suppress food intake through AKT signaling. Moreover, Raptin-mediated AKT signaling and glutamate-mediated cAMP signaling did not show mutual effects. Our findings give a hint to explain the diverse GRM3-mediated effects mediated by Raptin or glutamate. On the one hand, the key binding residues of GRM3 for its known ligands are different from the key residue for Raptin binding,58 which might cause differential conformational changes of GRM3. On the other hand, it is well established that GPCRs can mediate different downstream signalings by coupling different G proteins (including Gs, Gi, Gq).59 GPCR coupling to Gi can inhibit cAMP cascade while their coupling to Gq can stimulate the AKT pathway.59 Previous studies have reported that GRM3-mediated signaling results in the inhibition of cAMP signaling and activation of AKT signaling.60,61 The glutamate–GRM3 complex inhibits the cAMP cascade by coupling to Gi.56 However, whether the Raptin–GRM3 complex couples to specific G proteins to control the AKT pathway and inhibit appetite needs to be further explored.

Of note, GRM3 is expressed in various metabolic organs, such as the hypothalamus, stomach, muscle, and fat tissues. Here, we showed that Raptin-GRM3 signaling in the PVN and stomach markedly affects appetite. In addition, given that leptin from fat tissues is a canonical hormone involved in the appetite control, we tested the leptin concentration in PVN-specific Rcn2 knockout mice. The unchange of plasma leptin levels suggested that Raptin-GRM3 signaling in adipose tissues does not affect appetite via alterations in leptin. However, whether Raptin regulates appetite and body weight through the skeletal muscle or fat tissues still needs to be explored.

Of clinical significance, firstly, numerous experimental and approved clinical medicines targeting specific receptors (such as MC4R, GLP1R and LepR) are currently being targeted to treat obesity.62,63,64,65 In this respect, it would be worthwhile to utilize the newly identified receptor GRM3 for further anti-obesity drug discovery. Secondly, we revealed the association of sleep-affecting Raptin levels with human metabolic obese traits. Participants suffering from sleep deficiency exhibited lower Raptin levels and aggravated obesity, whereas patients with obesity that underwent SRT had higher Raptin levels and alleviated obese phenotypes. These findings further emphasize the importance of sleep quality on metabolic homeostasis. Thirdly, we found that individuals with RCN2 nonsense variant suffered from obesity. Our study confirmed that the protein encoded by RCN2 nonsense variant could not be secreted, and thus could not bind to GRM3 to exert the downstream effects. In addition, given that individuals with the heterozygous variant showed obese phenotypes, we could not exclude the possibility that mutated Raptin affected WT Raptin levels in a dominant-negative fashion. Further exploration regarding the mechanism by which this heterozygous variant is involved in obesity is warranted.

Taken together, our study identify Raptin as a unique hypothalamic hormone that cooperates with GRM3 to suppress appetite and obesity, thus providing a potential new avenue to treat obesity.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Company (Hunan, China). Grm3flox/flox mice (Cat# S-CKO-00640), Cas9-EGFP[KI/+] mice (Cat# C001475), Pomc-Cre mice (Cat# C001448) and AgRP-Cre mice (Cat# C001249) were purchased from Cyagen Bioscience. The Avp-Cre mice (Cat# 023530) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Sim1-Cre mice were designed and constructed by Cyagen Bioscience. To generate Sim1-Cre mice, a PCR amplicon containing an optimized internal ribosome entry sequence fused to Cre recombinase was inserted 3 bp after the Sim1 stop codon. Rcn2flox/flox and the complete Rcn2 knockout mice were purchased from BRL Medicine Inc. To generate Rcn2-floxed mice, two flox sequences were inserted into the two termini of Rcn2 exon 2 by using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. For genotyping, related reagent (AG12201) was purchased from ACCURATE BIOTECHNOLOGY(HUNAN) CO.,LTD, ChangSha, China. The genomic DNA was extracted from tail tips, and the primers of genotyping are:

Rcn2-L-loxp-F: TTCGCTCTAGGAGACCCTG;

Rcn2-L-loxp-R: GTCTTTGCTGCTCTTCGTG.

Rcn2-R-loxp-F2: AGTTCTTATGCCTGGAAGGTG;

Rcn2-R-loxp-R2: AAAGGTTTGGGCAAGTGTC.

Grm3-loxp-F: ATGTGGCACTCAGTTCCCAAATTA;

Grm3-loxp-R: GTCCTGCTATAGCTCAGTAGACAA.

Sim1-Cre-F1: TGGTTATGCCCTGGAACACTTAT

Sim1-Cre-R1: CCTTCCATGTGGTATACATGCTT

Sim1-Cre-F2: GCATGCCTATACATTGACTGGTTAT

Sim1-Cre-R2: CTTTGGCGAGAGGGGAAAGAC

Rcn2-KO-F: GAGAGGCCTTAGCAAGAGCG;

Rcn2-KO-R: AAGGTTTGGGCAAGTGTCTC.

Cas9-EGFP-F1: TGAGCGACATCCTGAGAGTG;

Cas9-EGFP-R1: GAGAGCTTTCAGCAGGGTCA.

Cas9-EGFP-F2: AAGGGAGCTGCAGTGGAGTA;

Cas9-EGFP-R2: CCGAAAATCTGTGGGAAGT.

Pomc-Cre-F: GCGGTCTGGCAGTAAAAACTATC;

Pomc-Cre-R: GTGAAACAGCATTGCTGTCACTT.

AgRP-Cre-F: GCTTCTTCAATGCCTTTTGC;

AgRP-Cre-R: AGGAACTGCTTCCTTCACGA.

The mice were housed in standard, specific pathogen-free facility at the Laboratory Animal Research Center of Central South University with controlled temperature (22–24 °C) and a 12-h dark/light cycle. The mice had free access to standard food (Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Company, China) or high-fat food (Biopike, D12492) and water. The mice were maintained in good health and utilized for in-house mating to ensure an adequate supply for experiments. All animal care protocols and experiments were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of the Laboratory Animal Research Center at Xiangya Medical School of Central South University.

Human sample studies

The participants were recruited from Xiangtan First People’s Hospital. Blood samples from participants were centrifuged at 4 °C soon after sampling, then separated and stored at –80 °C. The studies were approved by the Ethics Committee at Xiangtan First People’s Hospital and written informed consents were obtained from all participants before collecting clinical data and samples (Ethical no. 2023110814, Ethical no. 2023063010). Plasma levels of Raptin and other biochemical index were measured using MS analysis and Sandwich ELISA assay.

Human brain tissues

Human brain tissues used in the study were obtained from Human Brain Bank of Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University. The studies were approved by the Ethics Committee at School of Basic Medical College, Central South University (Ethical no. 2020KT-37).

Cell culture

Hypothalamic GT1-7 neurons and HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM (Procell, PM150210) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin (Pen), 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Strep) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humid atmosphere. Primary hypothalamus neurons were prepared from E18/19 mouse embryos as previously described.66 Briefly, the hypothalamus was dissected from E18/19 mouse embryos and kept in ice-cold dissection buffer containing HBSS (without CaCl2 and MgCl2), 1 M HEPES, and 1% Pen/Strep (v/v). A single-cell suspension was obtained through papain dissociation. Cells were then resuspended in neuronal plating media, composed of neurobasal media supplemented with 2% B27, 0.5 mM L-GlutaMAX, 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% FBS (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 30 μg/mL insulin (Sigma Aldrich). The cell culture was maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator chamber under a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

For the experiments of glutamate treatment, GT1-7 neurons were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. To maintain a low concentration of ambient glutamate, cells were co-transfected with the cDNA of the glutamate transporter EAAC1 and incubated in DMEM Glutamax medium for at least 2 h before the different drugs were administered. Then GT1-7 cells were treated with glutamine-free medium containing 10 ng/mL Raptin or 50 μM glutamate for 30 min.

For the experiments of testing Raptin accumulation in cell lysates, the cells were treated with brefeldin A (5 ng/mL) plus monensin (5 ng/mL).

For the experiments testing Raptin accumulation in cell culture medium, the medium was collected and concentrated via ultrafiltration tube. The aprotinin (HY-P0017), LY2794193 (HY-119243), LY379268 (HY-103558), LY341495 (HY-70059) and VU0650786 (HY-108710) were purchased from MCE.

SF model

For construction of SF mouse model, the intervention was performed as previously described.67 Each mouse was placed in an SF separate chamber. Mouse sleep is polyphasic, resulting in multiple bouts of sleep lasting 2–4 min throughout their sleep cycle. Thus, the sweep bar mounted at the bottom of the chamber moved along the bottom of the cage every 2 min during the ZT0–ZT16 to interrupt the sleep and was stationary during the ZT17–ZT24 for 8 or 9 weeks. The period of ZT0–ZT12 was around onset of the sleep cycle with high sleep need. Therefore, the SF resulted in decreasing sleep duration and bout length, and in increasing sleep state transition and waking. Mice in the SF chamber was maintained in a standard, specific pathogen-free facility at a controlled temperature (22–24 °C), with a 12 h dark/ light cycle (07:00 to 19:00 light on), with standard food and water provided ad libitum and environmental enrichments.

Metabolic cages

Indirect calorimetry was performed using a promethion metabolic cage system (Sable Systems International, USA). Mice were placed individually in chambers for 3 days under controlled conditions at a controlled temperature with 12-h light/dark cycles. Mice had free access to food and water. Respiratory measurements were taken at 20-min intervals following an initial acclimation period. Energy expenditure was calculated using the Lusk equation: energy expenditure in Kcal/h = (3.815 + 1.232 × RER) × ({{rm{V}}_{O_{2}}}) in mL/min. Food intake was monitored within the metabolic chambers.

MS analysis

For MS analysis, proteins were extracted from the hypothalamus of mice with or without SF intervention. After digestion, samples were desalted using C18 Cartridges (Empore SPE Cartridges C18 standard density, bed I.D. 7 mm, volume 3 mL, Sigma Aldrich), concentrated by vacuum centrifugation and reconstituted in 40 mL of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid. LC-MS/MS sequencing and data analysis were conducted by Jingjie PTM BioLab (Hangzhou). Co. Inc. In brief, 100 mg peptide mixture of each sample was labeled using TMT reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the mass of the peptides was identified by a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer equipped with a Nanospray Flex source (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The MS/MS data were compared against the mouse fasta from UniProt using an in-house Proteome Discoverer (V2.4, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Only peptides assigned to a given protein group were considered unique.

Western blot analysis

Western blot was performed as previously described.68,69 Cells and tissues were lysed in the RIPA buffer (P0013B, Beyotime) with protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors (C600387, Sangon). The proteins of cell lysate were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. After blocking in 5% BSA, membranes were then incubated with the primary antibody at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody at 37 °C for 1 h. Protein bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence reagent and imaged by ChemiDoc XRS Plus luminescent image analyzer. The primary antibodies used were as follows: Rcn2 (10193-2-1201 AP, 1:1000, Proteintech), Flag (14793, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), Tubulin (11224-1-AP, 1:5000, Proteintech), His (TA150088, 1:1000, Origene), p-Akt (4060, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), T-Akt (4691, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), Grm3 (ab283572, 1:1000, Abcam), β-Actin 1202 (81115-1-R, 1:5000, Proteintech), Khc (1:2000), Cyto1 (4272, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology). Silver staining was performed using fast silver stain kit (P0017S, Beyotime) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

scRNA-seq analysis

scRNA-seq data were obtained from the NCBI SRA database (GSE87544, GSE119960, GSE132355, GSE132730, and GSE148568).70,71,72,73 The scRNA-seq data were integrated using the Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) algorithm, resulting in a final integrated reference dataset. Cells with gene counts below 500 or mitochondrial content exceeding 10% were excluded through quality control. Subsequently, 50,087 high-quality single cells meeting these criteria were retained for downstream analysis. Dimension reduction and clustering were performed using functions from Seurat V5.0.1. The cells were grouped into 27 clusters utilizing the FindClusters function with the top 20 principal components and a resolution parameter set at 0.7. Visualization was achieved through a 2D Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) algorithm using the RunUMAP and DimPlot functions. Marker genes for each cluster were identified using the FindAllMarkers function in Seurat, which compared positive markers within a given cluster against all remaining clusters.

Screening for endopeptidases

Endoprotease screening of RCN2 protein was performed in the MEROPS database. The MEROPS website (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/merops) and database were established in 1996 to present the classification and nomenclature of proteolytic enzymes. This database contains all the world’s known peptidases and their substrate cleavage site information. In the database, each protease is assigned a unique number (Peptidase Code). In brief, the endoprotease was screened by inputting the amino acid sequence around the cleavage site of Raptin (NDGR-LDPQ) in the database for subsequent research.

Immunofluorescence staining and histochemistry

Mice were anesthetized and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, w/v in PBS) solutions were infused intracardially. Subsequently, the brains, adipose tissues or stomachs were paraffin embedded. The same embedding procedure was applied to human brains. Brain, stomach, and adipose tissue slices with a thickness of 5–10 µm were cut using a microtome (Leica VT1200). After paraffin removal and antigen retrieval of the slices, sections were blocked with blocking solution at room temperature for 2 h. Then they were incubated with the primary antibody working solution (diluted with blocking solution) at 4 °C for 48 h. The primary antibodies used in this study were as follows: RCN2 (10193-2-AP, 1:200, Proteintech), NeuN (ab177487, 1:500, Abcam), Iba1 (sc-32725, 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), GFAP (3670S, 1:200, Cell Signaling Technology), KLK4 (26547-1-AP, 1:200, Proteintech), KLK1 (10815-1-AP, 1:200, Proteintech), GRM3 (ab283572, 1:200, Abcam), c-Fos (ab208942, 1:200, Abcam), AVP (20069, 1:200, Immunostar), VIP (63269, 1:200, Cell Signaling Technology), GRP (20073, 1:200, Immunostar), Anti-His (12698, 1:200, Cell Signaling Technology), POMC (ab254257, 1:200, Abcam), NPY (ab120208, 1:200, Abcam). Subsequently, the sections were incubated with the secondary antibody working solution (diluted with blocking solution; 1:500, Thermo Fisher, including Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 555, Alexa Fluor 647, Alexa Fluor 594) at room temperature for 2 h. The slides were mounted by antifade with DAPI. Images were visualized on microscope or confocal microscope.

For multi-fluorescence staining, Tyramide signal amplification (TSA) technology was used when performing co-staining with primary antibodies of the same species origin. In brief, the first round of non-covalently bound antibodies was washed out by microwave treatment, and then a second round of incubation was performed with a secondary antibody. The cycle was repeated until all antibody incubations were completed, and the final images were obtained via microscope.

Full-length Rcn2 and Raptin synthesis

Full-length human RCN2 was purchased from Abcam (ab105594). Full-length mouse Rcn2 and Raptin were both synthesized by Sino Biological Inc (China). Briefly, protein expression was performed as follows: 1) The target gene sequence (GCGGAGGAACTGCACTACCCGCAGGGCGAGCACCGGGCGGACTACGACCGCGAAGCGCTGCTGGGTGTCCAGGAAGACGTCGATGAGTATGTTAAACTTGGCCACGAAGAGCAGCAAAGACGATTGCAGTCGATCATAAAGAAAATTGACTCGGACTCTGATGGCTTTCTTACTGAAAATGAACTCAGTCAGTGGATTCAGATGTCTTTTAAGCATTACGCTATGCAAGAAGCCAAGCAGCAGTTTGTGGAGTATGATAAGAACAGCGACGGCGCTGTGACGTGGGATGAGTACAACATCCAGATGTACGACCGGGTGATTGACTTTGATGAGAACACTGCTCTGGATGACACAGAAGAGGGGTCGTTCAGGCAGCTTCATCTAAAGGATAAGAAGCGATTTGAAAAAGCTAACCAGGATTCAGGTCCTGGTCTGAGTCTTGAAGAGTTCATTGCGTTTGAGCACCCTGAAGAAGTTGACTATATGACGGAGTTCGTCATCCAAGAGGCTTTGGAAGAACATGACAAAAATGGCGATGGGTTTGTTAGTTTGGAAGAATTTCTTGGCGATTACAGGCGGGATCCAACTGCAAATGAAGACCCAGAATGGATACTTGTTGAAAAGGACAGATTTGTGAATGATTATGACAAAGATAATGATGGCCGGATCACCACCATCACCACCATCATCACCATTAA) was inserted into baculovirus vector followed by the generation of the recombinant baculovirus according to the manufacturer’s manual. 2) Recombinant baculovirus was amplified in cells to prepare high-titer virus stocks. 3) For protein expression, cells were infected with recombinant baculovirus following standard protocols and target protein was expressed under optimal conditions. Protein purification and analysis were performed as follows: 1) Cell culture supernatant was collected via centrifugation and loaded onto an affinity purification column. 2) Target protein was eluted from the column using elution buffer. Fractions containing the protein of interest were pooled and subjected to buffer exchange into formulation buffer. 3) Protein concentration of the final product was determined by UV or BCA assays. 4) The purity of the final product was analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Raptin treatment

For cell experiments, Raptin was used at 10 ng/mL for 30–60 min. Control group was treated with vehicle (PBS).

For electrophysiological experiments, Raptin was dissolved in ACSF at a concentration of 1 ng/mL and incubated with brain slices for 5–20 min. The firing rates of neurons were detected before and during Raptin incubation.

For ICV infusion of Raptin in vivo, Raptin was loaded into a sustained release pump and sustained released at a dose of 40 ng/h/g body weight at the indicated time ( ~12 days or 4 weeks). In the study of WT mice with HFD feeding, ICV infusion was initiated at 9 weeks and sustained for 12 days. In the study of SF mice or Sim1Cre;Rcn2flox/flox mice, ICV infusion was initiated at the 5th week of SF intervention and sustained for 4 weeks. In the study of Sim1Cre;Rcn2flox/flox mice with HFD, ICV infusion was sustained for 4 weeks.

Raptin was administered into dual tissue-specific Grm3 knockout mice via tail vein at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day every other day for 8 weeks. Raptin was injected intraperitoneally into WT mice once at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day. Control, vehicle-treated mice were injected with PBS.

Antibody development