Atomic scale determination of magnetism and stoichiometry at the La0.7Sr0.3MnO3/SrTiO3 interface: investigation of inverse hysteresis

Introduction

Symmetry breaking at the interface of transition metal oxide (TMO) thin films is known to lead to unexpected electronic and magnetic properties by triggering electronic and structural reconstructions1. Discontinuities in the electronic state, atomic structure, chemical valence and orbital occupancy at the interface play important roles in modifying not only the lattice structure and charge transfer at the interface but also in modifying exchange interactions. For example, at the heterointerface, the charge transfer caused by a difference in chemical potential or by the screening of local dipoles can modify the valence state of TMOs1,2,3,4. These interfacial reconstructions and strong coupling between charge and spin in correlated electron systems yields a variety of new physical properties and functionalities, such as high-temperature superconductivity, ferroelectricity, magnetoelectric coupling and exotic complex magnetic ordering, which are absent in their bulk form5,6,7,8. Additionally, nonstoichiometry, which commonly arises in materials at the interface of heterostructures, yield surprising electronic and magnetic properties via unintentional doping, defects, or electronic reconstruction induced via polar mismatch close to the TMO interface9. Examples include the formation of a highly mobile 2D electron gas10,11 or the observation of in-plane ferromagnetic order12 at the interface between two insulating LaAlO3–SrTiO3 oxides.

The mixed-valence manganite La1−xSrxMnO3 is an important TMO system that has been extensively investigated in thin film form for its room-temperature half-metallicity13,14 and large magnetoresistance15 as a system for desirable applications in spintronic devices.

However, La0.67Sr0.33MnO3/SrTiO3 heterostructures display reduced magnetization16 and orientationally modified interfacial magnetism17. Notably, the magnetic properties of manganite thin films are highly sensitive to double exchange interactions, superexchange interactions and Jahn–Teller distortions, which can be altered via strain18,19, metal-oxygen bond length/angle20,21, and modified formal charge states of the interfacial ions22,23.

Several studies have focused on understanding the interface magnetism in manganite thin films grown on SrTiO3 (STO) substrates using different techniques, such as polarized neutron reflectometry (PNR) on La0.8Sr0.2MnO3/STO22 and surface sensitive X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) on La0.7Sr0.3MnO3(LSMO)/STO heterostructures24, to show that a variation in the Mn3+/Mn4+ ratio is important for the formation of an intermediate LSMO layer close to the interface.

In the last decade, several studies have addressed exotic magnetization reversal, including negative magnetic remanence and inverse hysteresis [positive (negative) coercivity in the descending (ascending) field cycle] mediated by intralayer exchange coupling within the LSMO layer of LSMO/STO(001) heterostructures. Recently, Mottaghi et al.25 reported a negative magnetic remanent state (inverse hysteresis) in a 7.6 nm thick LSMO film in a temperature range from 240 to 290 K. Saghayezhian et al.26 reported spontaneous magnetic reversal and inverse hysteresis in La2/3Sr1/3MnO3/STO heterostructures via DC magnetization and, on the basis of the results of atomically resolved transmission electron microscopy/spectroscopy, suggested that a structural gradient in the oxygen octahedral network and oxidation state variation were responsible for the inverse hysteresis. These authors also showed that a specific oxygen partial pressure (40 mTorr) and a critical thickness [15 unit cell (u.c.)] are required for such complex magnetic behavior27. Recently, Guo et al.28 reported inverse hysteresis in an LSMO/PZT heterostructure as well.

Interestingly, in all the above mentioned studies26,27,28, the magnetic properties were measured by superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometry, and the coercivities of the measured samples were approximately 20 Oe or less, which is within the remanence limit of the superconducting solenoid. In such measurement systems, the magnetic field is not directly measured, and the presence of a remanent field can cause inaccuracies or errors up to 20–40 Oe and measurement artifacts, including inverse hysteresis29. Therefore, the claim of inverse hysteresis induced via antiferromagnetic (AFM) intra-layer exchange coupling in thin films with low coercivity ( < 30 Oe) remains controversial. Direct evidence for magnetic intra-layer exchange coupling, such as elemental magnetic depth profiling, has not been obtained in the above studies. Thus, the origin of such unusual magnetization reversal remains unclear.

In this work, we investigate the hysteresis behavior of different epitaxial La0.7Sr0.3MnO3/STO(001) heterostructures by detailed DC magnetization measurements, carefully considering the remanence effect of the superconducting solenoid. We discuss the microscopic origin of the electronic and magnetic properties at the interface and inter-layer close to the STO substrate in terms of the combined effects of structural reconstruction and modified Mn valence and the presence of Ti3+-induced magnetism at the LSMO/STO interface. From element-specific soft X-ray resonant magnetic reflectivity (XRMR) at the Mn and Ti L-edges, X-ray magnetic circular dichroism and high-resolution electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS), we demonstrate that the combined effect of the Ti3+ states and the modified ratio of Mn3+/Mn4+ close to the interface plays a vital role in modifying the interface magnetism and results in the suppression of the magnetic dead layer and proximity-induced ferromagnetism in the Ti ions.

Results and Discussion

Structural properties

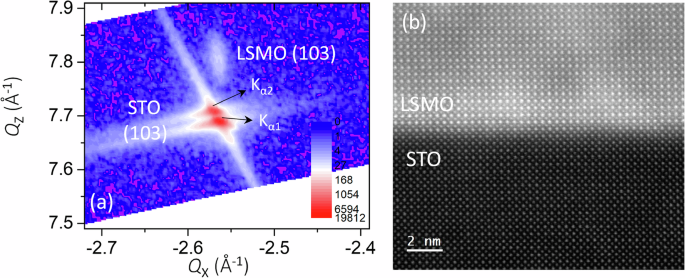

Single-phase LSMO thin films (pseudocubic bulk lattice parameter = 3.869 Å)19,30 were grown on STO(001) substrates by pulsed laser deposition (PLD). Reciprocal space mapping (RSM) around the asymmetric (103) plane, presented in Fig. 1a, shows that the LSMO thin film is epitaxial and fully strained to the STO substrate (same Qx for both the film and the substrate). The average calculated in-plane and out-of-plane lattice parameters are a = b = 3.902 Å and c = 3.843 Å, respectively (c/a = 0.984, corresponding to in-plane tensile strain). The aberration-corrected high angle annular dark field (HAADF)-scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image in Fig. 1b shows an atomically sharp LSMO/STO interface and confirms that the LSMO film is fully strained to the substrate with minimal defect density.

a Reciprocal space mapping around the asymmetric (103) Bragg reflection of 20 nm La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 grown on a SrTiO3(001) substrate. The arrows indicate the splitting of the substrate Bragg peak due to Cu-Kα1 and Cu-Kα2 radiation from the X-ray source. b An atomically resolved aberration-corrected STEM image of the cross-sectional view of the La0.7Sr0.3MnO3/SrTiO3 interface.

Magnetic properties

Temperature dependent field-cooled (FC) and zero field-cooled (ZFC) in-plane magnetizations under a 50 Oe magnetic field measured by SQUID are shown in Fig. 2a. From the magnetization versus temperature (M–T) behavior, we estimate that the paramagnetic to ferromagnetic ordering temperature (TC) of the thin film is 323 K [see the inset of Fig. 2a], which is consistent with the previously reported31 TC of strained LSMO. The anomaly in the M–T curve of LSMO around 105 K (Tsto) is attributed to the cubic to antiferrodistortive phase transition of the underlying STO substrate6,32,33,34,35,36. When the change in the lattice parameter is on the order of 0.1%, the epitaxially grown magnetoelastically coupled LSMO thin film is extremely sensitive to such breaking of symmetry, as shown by the low-field M–T data in Fig. 2a, which is suppressed at a high measuring field. Figure 2b, c show the magnetic hysteresis loops at different temperatures measured under zero-field cooled conditions. The saturation magnetic moment of the LSMO layer is 3.85 µB/Mn [see the inset of Fig. 2b], similar to the bulk value, indicating that the film is fully magnetically polarized with no interfacial dead layer. We discuss this aspect later in the EELS section.

a FC and ZFC temperature-dependent in-plane magnetization M-T of the LSMO/STO heterostructure with a 50 Oe cooling field; the inset shows dM/dT. Magnetization hysteresis before remanent field correction at (b) 5 K, (c) 90, and 300 K [inset in (c) shows the descending field cycle at 90 and 120 K]. Magnetization hysteresis after correcting the remanent field of the superconducting solenoid using a Pd reference sample at (d) 5 K and (e) 90 K. f Minor hysteresis loop (before remanent field correction) measured using different field cycles at 90 K. Schematic of the magnetic field cycling sequence (g) and calculated remanent field (h) of the superconducting solenoid at 90 K using the Pd reference sample. i Minor hysteresis loop after remanent field correction at 90 K.

Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the magnetization hysteresis recorded at 5 K displays an inverse hysteresis behavior, namely, positive Hd and negative coercivity Ha in descending (positive to negative) and ascending (negative to positive) field cycles, respectively, with very small coercivity (∼12 Oe), as shown in Fig. 2b. Such negative remanence behavior has been previously reported for multilayer systems, typically resulting from interlayer AFM exchange coupling between magnetic layers possessing different uniaxial anisotropies, for example, [Co-Pt]/[Gd-Pt]37 (coercivity > 1 kOe) and Co/Mn/Co38 (coercivity > 100 Oe), and also recently in LSMO/STO heterostructures25,26, as discussed in the introduction.

This inverse hysteresis behavior in the magnetization reversal is also observed across the structural phase transition temperature (105 K) of STO, as shown in Fig. 2c, with no significant changes in the magnetization response, which is in agreement with previous observations36 [inset Fig. 2c], indicating that the inversion is not related to the structural phase transition of the STO substrate31,39. We find that the negative coercivity of the heterostructure increases with increasing temperature and persists up to room temperature, a behavior opposite to that expected from the intrinsic magnetic behavior of ferromagnetic materials40,41, where the thermal excitation tends to favor the formation of reverse domains and domain wall motion. The behavior of the inverse hysteresis as a function of the angle ϕ between the sample plane and the applied magnetic field is shown in Fig. S1 of the supplementary information. Upon rotation of the sample in the out-of-plane direction, the coercivity of the sample increases (up to 50 Oe), and the M‒H loop transforms to a normal hysteresis loop (Fig. S1 in the supplementary section).

We note that the in-plane coercivity of the LSMO layer measured here is approximately 20 Oe or less, as noted in recent publications26,27,28, which is below the remanence limit (20‒40 Oe) of the superconducting solenoid of SQUID magnetometers. This can potentially lead to measurement artifacts, including inverse hysteresis29. Therefore, to exclude the effect of the remanent field of the superconducting solenoid, we performed detailed magnetization measurements on a paramagnetic palladium (Pd) reference sample to calculate the remanent field of the superconducting solenoid. Interestingly, after the remanent field is corrected, the inverse hysteresis recorded at 5 and 90 K transforms into normal M‒H curves, with a wasp-waisted or pinched shape, as shown in Fig. 2d, e31,42,43. We confirm this result by measuring minor loops at 90 K after applying +20 kOe for a set of increasing reverse fields from –80 Oe to –12 kOe. The results are presented in Fig. 2f. We find that, as we increase the reverse field, the coercivity for the ascending branch Ha decreases and flips sign at a certain reverse field (between –1 and –5.5 kOe), similar to the positive exchange bias reported in the LSMO/PZT heterostructure28. To confirm whether this behavior is intrinsic to the system, we used the measurement protocol schematically shown in Fig. 2g on a Pd reference sample to determine the variation in the remanent field of the superconducting solenoid with increasing reverse field strength. We find that the remanent field remains the same in both descending ( + ve to –ve) and ascending (–ve to +ve) loop branches to within ± 4 Oe. Furthermore, we see that the remanent field remains approximately constant up to -2 kOe and flips sign for reverse fields exceeding –4 kOe, as shown in Fig. 2h Once the remanent field in the minor loop is corrected for, the exotic positive exchange bias behavior disappears [Fig. 2d, e, i]. These results were confirmed by performing similar measurements on a second 20 nm LSMO/STO(001) sample grown under identical conditions, where we observe a similar inverse hysteresis behavior, as well as a transition from inverse hysteresis to normal hysteresis at 30 K during cooling (260 to 5 K) [shown in Fig. S2 in the supplementary section], which transforms into a normal hysteresis behavior after correcting the remanent field of the superconducting solenoid, and displays an increase in coercivity with decreasing temperature, characteristic of ferromagnets (Fig. S2)40,41. The observation of a regular M‒H loop for a magnetic field applied out of plane, where the coercivity is higher than the remanent field of the solenoid, is consistent with the explanation given above. Thus, we find no evidence for the presence of inverse hysteresis in LSMO/STO and attribute its observation in low coercivity systems to artifacts from the remanent field value of the superconducting solenoid, which needs to be considered when the data are evaluated29.

Electronic properties

Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) results

To evaluate the effects of interface chemistry and charge redistribution on the electronic structure and magnetic properties across the LSMO/STO heterointerface at the atomic scale, we performed atomically resolved aberration-corrected STEM-EELS spectrum imaging at room temperature. A HAADF-STEM image and elemental EELS map of the sample are shown in Fig. 3a. The STO substrate is SrO-terminated in this particular local region. We observe the periodic octahedral tilt of LSMO close to the interface and cannot identify any strong modifications in the structure close to the interface, as shown in the HAADF image.

a Local oxygen octahedra across the LSMO/STO heterointerface in an atomically resolved HAADF-ABF STEM image along with EELS mapping across the LSMO/STO heterointerface; the rectangular areas (numbered from 1–14) correspond to the scanned regions used to collect the EELS spectra. Layer-resolved EELS spectra at the (b) Mn L-edge and (c) Ti L-edge. (d) Calculated L3/L2 ratio and Mn L3 peak position as a function of the scanned area. e Deconvolution of Ti3+ and Ti4+ spectra from the experimental spectra via a linear sum of Ti L-edge reference spectra for Ti4+ (orange) and Ti3+ (blue) taken from Wang et al.45. f Calculated interfacial Ti valence and the relative Ti3+ fraction as a function of the interfacial scanned area.

As we go across the interface from LSMO to STO (bottom to top), the EELS line profile gradually changes from a Mn-edge dominated spectrum to a Ti L2,3-edge dominated spectrum [Fig. 3b, c]. The variation in the spectral weight ratio of the Mn L3 and Mn L2 features clearly indicates that the stoichiometry of the LSMO thin film close to the interface along the surface normal is nonuniform (Fig. 3b). To quantitatively obtain the formal valence of Mn near the LSMO/STO interface, the ratio L3/L2 is calculated from the integrated area of individual Mn L3 and Mn L2 peaks after background subtraction following the work of Varela et al.44 and Wang et al.45. It can be seen that the L3/L2 ratio increases near the LSMO/STO interface, indicating a decrease in the Mn valence state (from a mixed Mn3+/Mn4+ state to a Mn3+ rich state), as shown in Fig. 3d. This observation is also consistent with the peak position shift (toward lower energy) shown by the vertical line in Fig. 3b, which we attribute either to oxygen deficiency46,47 or to a compensating interface charge48. This Mn3+ enriched interface prevents the formation of a dead layer49,50.

We also observe a significant change in the Ti L-edge EELS spectra across the interface, namely, a reduced oxidation state of Ti along with a small Ti3+ fraction [Fig. 3(c)] close to the interface. The presence of Ti3+ can be quantitatively determined by deconvoluting the reference spectra of Ti4+ and Ti3+, as shown in Fig. 3(e), following the work of Ohtomo et al.51 and Wang et al.45 These results show that the relative fraction of Ti3+ gradually increases from the STO to the LSMO/STO interface, whereas the Ti4+ valence decreases, as shown in Fig. 3(f). The presence of Ti3+ (3d1 state) explains the origin of the unusual magnetic dichroism observed at the Ti L-edge in soft X-ray resonance reflectivity measurements (shown in Fig. 4).

a XAS spectra for σ+ and σ− helicity and corresponding XMCD in TEY mode at the Mn L-edge at 12 K. b Temperature-dependent dichroic X-ray reflectivity (Ip-Im) energy scans across the Mn L-edge. c X-ray reflectivity energy scan for σ+ and σ− helicity across the Ti L-edge at 12 K. d Temperature-dependent dichroic X-ray reflectivity energy scans across the Ti L-edge. e Schematic energy level diagrams of the orbital hybridization proposed for FM and AFM spin‒spin coupling between Ti and Mn with preferentially occupied Mn 3d–eg orbitals and relative occupancies of the Ti 3d-xz,yz orbitals at the electron‒doped titanate and a manganite interface in LSMO/STO heterostructure58,63.

In the O K-edge EELS spectra, we observe a significant modification and a small damping in the O K-edge features/fine structure (see Fig. S3 of the supplementary information) only across the interface, indicating the presence of oxygen vacancies at the interface46.

From these results, we can also rule out mutual charge transfer from Mn to Ti because both valence states of the Mn and Ti ions are reduced toward the interface, which we instead associate with a small density of O vacancies. Notably, the presence of oxygen vacancies at the LSMO/STO interface and reduced Mn species has been reported in other studies, such as that by Nord et al.52. It has also been suggested that the formation of oxygen vacancies at the interface diminishes the polar field at the interface and suppresses the mutual charge transfer from Mn to Ti23,53. The presence of oxygen vacancies is expected to result in electron/hole doping and affects the superexchange and double-exchange interactions at the interface. On the basis of the gradient in the Mn/Ti valence state variation and O K edge EELS, we conclude that the oxygen vacancies are confined to the interface (up to 5–6 uc) and are not induced by the O2 partial pressure during growth. These results imply that the charge imbalance induced by the presence of oxygen vacancies at the interface has an important role in stabilizing the modified electronic and magnetic states at the interface48.

XMCD and X-ray resonant magnetic reflectivity (XRMR) results

To directly explore the interfacial magnetism of the LSMO/STO heterostructures and the role of phase separation and off-stoichiometry on the overall magnetic and electronic properties, we carried out XRMR measurements at the Mn and Ti L-edges. XRMR is sensitive to the magnetic depth profile and provides element-specific information about the magnetic spin configuration at the LSMO/STO interface. XMCD measurements were performed in surface sensitive total electron yield (TEY) mode along with bulk sensitive scattering mode in a reflectivity geometry. The absorption spectra in TEY mode at the Mn L-edge recorded at 12 K in the field-cooled remanent state (following a similar protocol used for the SQUID measurements) exhibit a very strong characteristic XMCD signal (24%), as shown in Fig. 4a. The XMCD sum rules54,55,56,57,58 give an effective magnetic moment of meff = 2.22 ± 20% µB/Mn (see Fig. S4 of the supplementary information), which is slightly reduced with respect to the remanent magnetic moment value, as observed by SQUID VSM measurements (Fig. 2d). This reduced magnetic moment might be attributed to reduced magnetization at the surface of the film at low fields, which strongly influences the TEY XMCD signal, as it decays exponentially with depth. To probe deeper into the LSMO layer, we measured the reflected intensity for the two helicities as a function of energy (energy scan) across the Mn L-edge at an angle of 30° from the surface, where the probing depth is limited by the X-ray attenuation length of approximately 80 nm (much larger than the film thickness). The corresponding dichroic spectra for temperatures ranging from 12 to 319 K are shown in Fig. 4b. In addition to the expected reduction in the signal amplitude with increasing temperature, we observed a strong change in the dichroic reflectivity, indicating a magnetization redistribution as a function of depth with temperature.

Furthermore, the dichroic reflectivity across the Ti L-edge energy range presented in Fig. 4c show a notable (2.5%) dichroic signal (XMCD) at 12 K, as shown in Fig. 4d, revealing the presence of magnetism59,60 at the STO interface and the presence of Ti3+ at the LSMO/STO interface, which is consistent with the observations in the EELS measurements. Owing to the limited escape depth of electrons, no TEY signal at the Ti edge could be detected. The magnetic polarization of Ti is also confirmed by the measurement of a circular dichroic signal in X-ray resonant magnetic reflectivity measurements at the Ti L edge, as shown in Fig. S5. The dichroism at the Ti L-edge is nearly eight times weaker than that at the Mn L-edge. The relative signs of the Mn L3-edge dichroism in the surface-sensitive TEY signal and bulk-sensitive reflectivity at the Mn and Ti L3-edge are the same, demonstrating that the Ti and Mn magnetic moments are oriented in the same direction. In addition, we find that the intensity of the Ti magnetic dichroic reflectivity decreases with increasing temperature and has a similar temperature dependence as the Mn dichroic reflectivity signal, demonstrating that the Ti magnetic polarization follows that of Mn, i.e., that the Ti spins are ferromagnetically coupled to the Mn spins. Overall, these results indicate that Ti magnetism has an interfacial origin and is ferromagnetically coupled to the moment of the Mn site in the nonstoichiometric Mn3+-rich interfacial LSMO layer close to the STO substrate58,61.

Garcia Barriocanal et al.58,62 experimentally demonstrated that, for electron-doped titanate/manganite superlattice, the sign of spin‒spin coupling interaction between the Mn and Ti spin moments at the electron-doped titanate and the manganite interface can be tuned from antiferromagnetic to ferromagnetic by the strain state of the superlattice, which is explained in terms of changes in the preferential occupation (orbital polarization) of the Mn 3d eg orbitals and is controlled by the manganite to titanate thickness ratio tr (tLMO/tSTO). For the large tr and relaxed LaMnO3 layer, these authors observed antiferromagnetic Ti–Mn magnetic coupling (schematically shown in Fig. 4e), whereas for the strained film (low tr with 3dx2−y2 preferential occupation), they observed ferromagnetic Ti–Mn magnetic coupling at the interface63. In our case, the thin films are fully tensile-strained, and the interface has a similar structure. The manganese Mn 3dx2−y2 orbitals are preferentially occupied, and the hybridization between the occupied Mn 3dx2−y orbitals and Ti orbitals across the interface is weak. A finite overlap between the Ti t2g orbitals and the Mn d3z2−r2 orbitals resulting from the GdFeO3-type distortion of manganite may yield finite values of the transfer integral between the 3z2 − r2 orbitals and the active t2g-dxz and dyz orbitals. A ferromagnetic coupling between the moment at the Ti and Mn sites results from the superexchange interaction through the virtual excitation of electrons from Ti t2g (dxz, dyz) to Mn d3z2>−r2, as schematically shown in Fig. 4e58,63.

EELS, element-specific XMCD, and magnetic reflectivity experiments show that the LSMO/STO heterostructure behaves like a trilayer system: a bulk LSMO layer, an interfacial LSMO layer and an interfacial STO layer, which are chemically and magnetically distinct from each other. We point out that, in the remanent state, the interfacial Ti magnetic moment (probed by highly sensitive XRMR) and the Mn magnetic moment (TEY absorption) in the top bulk layer are parallel to each other in contrast to the antiparallel alignment in the LSMO/STO superlattices and thin films24,48. However, we cannot establish from the XAS measurements the magnetic moment orientation of the Mn ions of the LSMO interlayer close to the STO and the bulk-like LSMO top layer.

To obtain this information, we carried out polarized soft X-ray resonant magnetic reflectivity measurements to probe the magnetization profile64,65,66,67,68,69 across the entire sample thickness for the Mn ions. X-ray resonant magnetic reflectivity curves Ip recorded with σ+ helicity and Im recorded with σ− helicity were collected in a longitudinal geometry using photon energies tuned to the Mn L3-edge (642 eV), as shown in Fig. 5a. The symbols in Fig. 5b represent the experimental magnetic asymmetry defined by (Ip–Im)/(Ip + Im) measured at the base temperature of 10 K. The experimental asymmetry data were fitted using the DYNA program66,70,71, and the best fit to the experimental data is shown by the solid line in Fig. 5b. All the parameters corresponding to the different slices of thin films used for fitting the soft X-ray resonant magnetic reflectivity data are listed in Table S1 in the supporting information. The asymmetry drops to zero at high angle and the fitting parameters (angles ϕ and γ) corresponding to the magnetization direction70 are 90°, indicating that the magnetic moments lie in the film plane. The reconstructed element-specific magnetization depth profile for Mn is shown in the inset of Fig. 5a. The magnetization depth profile clearly shows that the magnetization of the LSMO layer is not uniform close to the STO interface and slightly reduced but not reversed. The reason for the reduction in Mn moment in the bulk of the film is difficult to ascertain. Since we obtain near-bulk moments from the SQUID measurements, we attribute the reduced moments to the presence of magnetic domains not fully oriented in the direction of the original magnetic field. At the interface with the STO, the additional reduction is attributed to the presence of oxygen vacancies and the presence of a Mn3+-rich phase that suppresses the magnetization close to interface compared to the rest of the 30%-hole-doped LSMO layer. We normalized the magnetic moment in the magnetization depth profile by the remanent magnetization observed by SQUID VSM measurements, and the average calculated magnetic moment obtained from the resonance reflectivity fit is mtot = 2.37 µB/Mn, which is consistent with the XMCD result. In addition, we also simulated the experimental magnetic asymmetry for two different models consisting of a very thin (2 uc) LSMO dead layer (DL) at the interface in the first model and a 2 uc LSMO layer with (20%) negative magnetization (NM) at the interface in the second model. The experimental and simulated magnetic asymmetries and the extracted magnetic depth profiles for these two models are shown in Fig. 5c and d, e, respectively. The simulated magnetic asymmetry does not describe the experimental asymmetry in either case. The results from our element-specific XRMR measurements and the DYNA simulations clearly rule out the possibility of the presence of an inverse magnetized layer at the LSMO/STO interface.

a Specular soft X-ray reflectivity curves Ip and Im at the Mn L3-edge resonant energy of 642 eV. b Experimental and calculated magnetic asymmetry at 10 K. The inset of (a) represents the element-specific magnetization depth profile for the Mn ion derived from the best fit of the magnetic asymmetry. c Experimental and calculated magnetic asymmetry with models considering the dead layer (DL) and negative magnetization (NM) at the LSMO/STO interface (up to 3 uc) and their respective magnetic depth profiles (d, e) for the Mn ion, derived from the refinement of the magnetic asymmetry.

Conclusion

In summary, we have investigated the effects of interfacial nonstoichiometry on the magnetic properties of the epitaxial La0.7Sr0.3MnO3/SrTiO3(001) oxide heterostructure. We have demonstrated that the observation of the inverse hysteresis behavior in low coercivity LSMO thin films emanates from the remanent field of the superconducting SQUID-VSM solenoids and not from an antiferromagnetic intra-layer exchange coupling. A combined study of atomically resolved electron energy loss spectroscopy, element-specific X-ray magnetic circular dichroism and depth-sensitive polarized soft X-ray resonant magnetic reflectivity revealed the formation of a Mn3+enriched interfacial layer close to the SrTiO3 substrate, which is ferromagnetically coupled to the rest of the bulk-like top LSMO layer and leads to a proximity-induced ferromagnetism in Ti, which is mediated via interfacial oxygen vacancies. These results provide new insights to the understanding of the magnetism and spin structure of correlated oxide interfaces and also carry potential practical implications for spintronic and magnetic tunnel junction-based devices.

Experimental Section

Thin film growth and characterization

20 nm thick films of La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 were grown on single-crystalline [001]-oriented SrTiO3 substrates (with mixed SrO and TiO2 surface termination) by pulsed laser deposition (PLD) using a KrF excimer laser (248 nm). A single-phase stoichiometric La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 target was used for deposition. The films are grown at a substrate temperature of 750 °C under 350 mTorr of oxygen partial pressure and with 6 Hz repetition rate. During deposition, the energy density at the target surface was kept at ∼2.1 J/cm2. After deposition, the sample was cooled in an ambient oxygen environment (500 Torr). Structural characterization and reciprocal space mapping (RSM) were carried out using a high-resolution Bruker D8-Discover X-ray diffractometer equipped with a copper target. Macroscopic DC magnetization measurements were carried out in a 7-Tesla SQUID vibrating sample magnetometer (SVSM; Quantum Design Inc., USA) in the temperature range from 10 to 360 K. For correcting the remanent field of the superconducting solenoid of the SQUID-VSM, we used a high-purity paramagnetic Pd sample.

STEM imaging and Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (EELS)

Cross-sectional TEM specimens (lamella) were prepared with a Xe+ plasma-based focused ion-beam system (TESCAN S8000X). The sample surface was coated with a protective layer of thin carbon (Sharpie marker) followed by Pt (deposited by an e-beam following the ion-beam) before the milling process was started to prevent damage during lamella preparation. In situ lift-off was used to mount the lamella on a TEM half-grid utilizing a Kleindiek probe manipulator. The FIB lamella was milled at 30 keV and thinned at 10 and 5 keV, and final cleaning was performed at 2 keV. HAADF (and ABF)-STEM and EELS measurements were carried out at 200 keV using a probe-corrected JEOL NEOARM. The convergence angle was kept at 25–29 mrad, and the condenser lens aperture was at 40 µm with a camera length of 4 cm for STEM and 2 cm for EELS imaging, respectively. The GATAN GMS 3.5 software, a GATAN OneView IS camera and annular detectors were used to acquire and analyze the images along with a GATAN OneView IS camera and annular detectors. The stoichiometry and electronic structure at the interface were analyzed by atomically resolved electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS).

XMCD and soft X-ray Resonant Magnetic Reflectivity (XRMR)

To investigate the element-specific interfacial magnetism, temperature-dependent X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) measurements at the Ti and Mn L-edges was carried out at the BESSY II undulator beamline UE46-PGM1. Absorption spectra using two different X-ray photon helicities (σ+ and σ−) were recorded in surface sensitive TEY mode (by measuring the sample drain current) and in bulk sensitive scattering mode, respectively, in a reflection geometry at 30° grazing incidence via a dedicated three-circle ultrahigh vacuum zero-field diffractometer72. X-ray resonant magnetic reflectivity (XRMR) spectra at the Mn and Ti L-edge resonance energies were recorded at the same beamline for the two X-ray photon helicities (σ+ and σ−) at a base temperature of 12 K. The measurements were carried out in the remanent state after cooling under a magnetic field from the paramagnetic state down to 12 K by placing a permanent magnet close to the sample during cooling. The XRMR data were simulated and fitted via the DYNA Matlab program66,70,71. To fit the data, the imaginary atomic scattering factors for Mn were derived from X-ray magnetic circular dichroism measurements at the Mn L-edge performed on the same LSMO thin film, whereas the real part was obtained from the Kramers-Kronig transformation.

Supporting Information

In the supplementary information, we provide the details of angle-dependent magnetization hysteresis measurements performed on LSMO/STO(001) at 5 K. We present additional temperature-dependent magnetization hysteresis measurements on a second 20 nm LSMO thin film grown on STO(001). We present as well EELS spectra at the O K-edge across the LSMO/STO hetero-interface. We present the XMCD sum rule analysis to calculate the spin and orbital magnetic moments of the Mn ion. We show the TEY XAS measurement at the Ti L edge at the base temperature and the specular soft X-ray reflectivity at the Ti L-edge resonant energy at 10 K. We tabulate the fitting parameters of the soft X-ray resonant magnetic reflectivity (XRMR) data.

Responses