Relationship between network topology and negative electrode properties in Wadsley–Roth phase TiNb2O7

Introduction

In recent years, global warming has become more serious than expected worldwide, and countermeasures against it are among the most important issues we need to address. Greenhouse gases such as CO2 are considered to be the main cause of global warming, making it imperative to realize a low-carbon society via the effective use of renewable energy. The development of rechargeable batteries capable of storing renewable energy is essential to achieve this goal.

Given this background, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), which have been used as rechargeable power sources for small portable devices such as laptops since the 1990s, are now widely considered for use as large batteries for stationary applications, vehicles, etc.1,2. One of the serious problems associated with the use of large LIBs is the risk of ignition. To overcome this problem, the constituent materials of LIBs have been reviewed in recent years, and the use of transition metal oxides as negative electrode (anode) materials has been aggressively pursued3,4,5. Many commercially available LIBs have a carbon negative electrode with a low working potential (0.1–0.2 V vs. Li/Li+) to achieve a high energy density, but since the carbon operates near the Li metal deposition potential, there is a risk of internal short circuits due to Li metal deposition, especially when the battery is quickly charged. Therefore, replacing conventional carbon materials with oxides that operate at slightly higher potentials should reduce the risk of internal short circuits. Furthermore, oxides have excellent thermal stability, and thus, a considerable improvement in safety can be expected. Notably, the use of oxide-based negative electrodes, which are insulators in the fully discharged state, has the significant advantage of insulating the battery in the event of an accident. Indeed, Li4Ti5O12 (LTO) with a spinel structure that operates ca. 1.5 V vs. Li/Li+ has been commercialized, and LIBs with LTO-based materials as the negative electrodes are being implemented in society as rechargeable batteries for vehicles, considering their capability for high Li+ diffusion6,7,8. However, the theoretical capacity of LTO is 175 mA h g–1, which is very small compared with that of carbon, i.e., 372 mA h g–1.

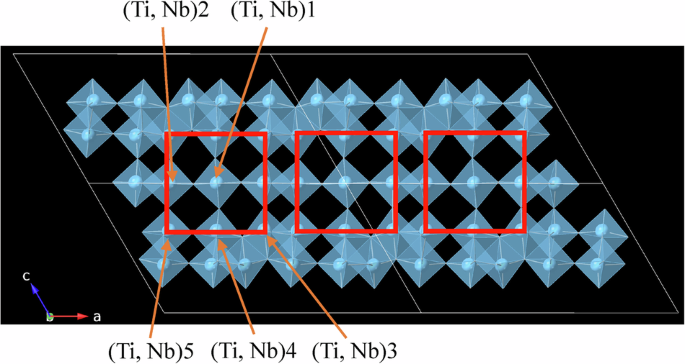

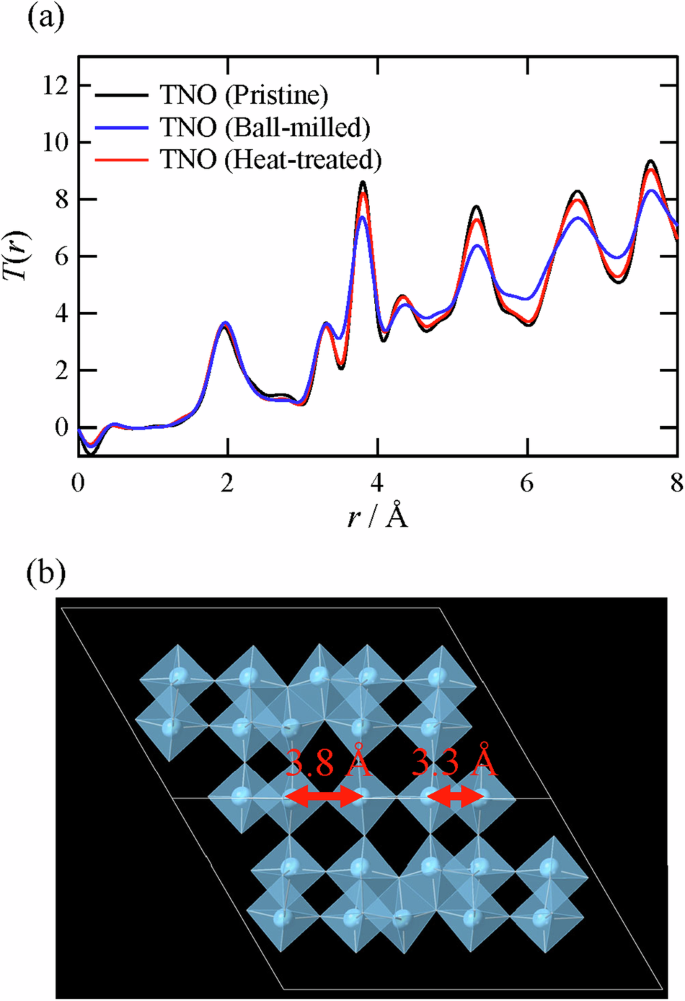

Thus, many studies have been devoted to the discovery of novel oxide-based negative electrodes with capacities exceeding that of LTO, and materials based on a perovskite (ABO3-type) structure are the most promising candidates. For example, (Li, La)NbO3, which lacks some of the A-site cations in the perovskite structure, has remarkable Li+ conductivity and has been widely studied as a solid electrolyte9,10,11. In addition, this material can function as a negative electrode12,13. Recently, Wadsley–Roth phase oxides have attracted even greater attention14,15,16,17,18,19,20. The basic framework of the Wadsley–Roth phases is a ReO3-type structure, in which A-site cations are completely absent from the perovskite structure (i.e., BO3-type structure), and in the phases, the corner-sharing BO6 octahedral blocks are sheared periodically (3 × 3, 3 × 4, and so on), forming edge-sharing regions or tetrahedral sites. In the case of TiNb2O7, which is a representative material of Wadsley–Roth phase electrodes21,22,23,24,25, TiO6 and NbO6 octahedra form 3 × 3 blocks (corner-sharing networks) with edge-sharing interfaces, as shown in Fig. 1, and lithium ions are considered to diffuse easily through the large free spaces (cavities) of the network20,26. In addition, many lithium ions can be inserted and deinserted by utilizing Ti and Nb redox reactions (Ti3+/Ti4+, Nb4+/Nb5+, and Nb3+/Nb4+); thus, its theoretical capacity (387 mA h g–1) is comparable to that of a carbon-based negative electrode material.

The red squares represent corner-sharing blocks, and the other parts are edge-sharing parts. The unit cells (monoclinic) are represented by white lines.

Although TiNb2O7 is considered a promising negative electrode material, much remains unknown about its atomic configuration, which is generally closely related to the negative electrode properties. For example, based on crystallography, a TiNb2O7 crystal has five cation sites occupied randomly by both Ti and Nb. On the other hand, a locally stable cation arrangement has been proposed via a computational method26. Therefore, a systematic elucidation of the atomic arrangements via an experimental technique would be highly beneficial. Furthermore, because the network of corner-sharing octahedra mainly forms the Li+ conduction pathway in the material20,26, the order/disorder of the network (the shape of the network) is considered closely related to the negative electrode properties. However, quantitatively elucidating such a network structure, which can be regarded as an intermediate-range structure, via conventional analysis of crystal structures is difficult.

Considering the above situation, to clarify the relationship between the negative electrode properties and the atomic configuration of Wadsley–Roth phase TiNb2O7, the material was prepared via different methods in this study, and the negative electrode properties were evaluated via galvanostatic charge/discharge cycle tests. Total scattering (diffraction) data were also measured with quantum beams, and reverse Monte Carlo (RMC) modeling using the data27,28,29 was performed in addition to Rietveld analysis using the Bragg peaks. Furthermore, topological analysis based on persistent homology (PH)30,31, which has recently attracted considerable attention in various fields, was carried out on the three-dimensional atomic configurations obtained via RMC modeling. Through these analyses, the relationship between the topology of the atomic configuration and the negative electrode properties was examined in detail. As a result, a guideline for material development with excellent electrode properties was developed for the first time on the basis of topology.

Materials and methods

Synthesis and characterization

In this study, three different TiNb2O7 samples were prepared according to the prior literature25,26: TiO2 (anatase) and Nb2O5 were mixed in an appropriate proportion, and the mixture was calcined in air at 1100 °C for 12 h. The as-synthesized sample is hereafter referred to as “TNO (Pristine)”. A portion of the pristine powder was placed in a container with ethanol and ground by ball milling at 600 rpm for 12 h (PL-7, FRITSCH). The powder obtained after drying at 100 °C is hereafter referred to as “TNO (Ball-milled)”. The ball-milled sample was then heat-treated in air at 650 °C for 1 h. The resulting sample was designated “TNO (Heat-treated)”.

Phase identification of TNO (Pristine), TNO (Ball-milled), and TNO (Heat-treated) was performed via X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements (Cu Kα; Empyrean, PANalytical). The metal composition was analyzed via inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP‒AES; ICPE-9820, Shimadzu). In this work, the total metal composition was normalized to 3. X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) spectra were also measured via transmission at BL01B1 (SPring-8), and the electronic structure was subsequently studied via the Athena program32. The particle morphologies of the samples were also evaluated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; JSM-7600F, JEOL), and the particle size distributions were investigated via a particle size analyzer (FPAR-1000, Otsuka Electronics).

Charge/discharge cycle test

For the charge/discharge cycle tests, an HS cell (Hohsen Corp.) was used. The prepared sample, Super C65, and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) were mixed at a weight ratio of 5:5:1 and then pressed onto an Al mesh. The pressed sample was used as the working electrode after vacuum drying. Li metal was used as the counter electrode, and a polypropylene film was used as the separator. The electrolyte was a solution of 1 mol dm–3 LiPF6 in EC:DMC with a 1:2 volume ratio (Kishida Chemical Ltd.). The cell was assembled under an Ar atmosphere in a glove box.

Galvanostatic charge/discharge cycle tests (HJ1001SD8, Hokuto Denko) were performed at room temperature using the assembled cell. The cutoff voltages for charging (Li+ insertion) and discharging (Li+ deinsertion) were set at 1 V vs. Li/Li+ and 3 V vs. Li/Li+, respectively. The current density was 38.7 mA g–1, corresponding to 0.1 C.

Average and local structural analyses

As a first step, synchrotron X-ray diffraction (λ = 0.8 Å; BL02B2, SPring-8) measurements were performed, and then the obtained diffraction pattern of TNO (Pristine) was analyzed via Rietveld refinement using the Rietan-FP program33 to determine the average structure (crystal structure).

To clarify the intermediate-range structures (disorder of the network) of the samples, neutron total scattering measurements (NOVA, J-PARC MLF) and X-ray total scattering measurements (BL04B2, SPring-8) were performed. Neutron total scattering data were collected with the 45° bank and then normalized to obtain Faber–Ziman structure factors, S(Q), using calibration data, i.e., scattering intensities of the background, a V-rod, and a V-Ni empty can. The X-ray total scattering patterns were measured at an incident energy of 61.4 keV, and the S(Q) were derived from them in a standard manner34. Reduced pair distribution functions, G(r), and total correlation functions, T(r), were also obtained from S(Q) via a Fourier transform relation35.

By RMC modeling using the total scattering data simultaneously, we constructed the atomic configurations of the samples using the RMCProfile code28. To extract information on nonperiodic structures (the local cation distributions and the disorder in the network structure), S(Q) was convolved by considering a simulation box size, and the convolved S(Q), denoted as Sbox(Q) hereafter, was used in the modeling. The initial simulation box (2 × 6 × 7 supercell) with 5040 atoms, Ti504Nb1008O3528, was made from the unit cell refined by the Rietveld analysis, and the cation distribution was optimized by exchanging Ti and Nb in the RMC modeling. Bond-valence-sum (BVS) constraints, in which the bond valence parameters were 1.815 and 1.911 (B = 0.37) for Ti4+–O2− and Nb5+–O2−, respectively, were applied to maintain appropriate Ti–O and Nb–O distances36,37. From the obtained atomic configuration snapshots, the octahedral distortions of TiO6 and NbO6 were estimated. To gain a deeper understanding of the atomic configurations, ring and topological analyses, described in the following subsection, were carried out.

Topological analysis

To quantitatively investigate the free spaces forming Li+ conduction pathways, the atomic structures, especially the network structure formed by the octahedra, were analyzed via the methods described below.

In this study, free spaces in the atomic configurations were calculated using Structural Order Visualization and Analysis (SOVA) tools developed by Shiga and a coworker38, and the Li+ conduction pathways were confirmed via BVS mapping with the PyAbstantia code39 using a bond valence parameter of 1.466 and B = 0.37 for Li+–O2−. The free spaces in TiNb2O7 were also characterized by ring size distributions, which were calculated using the R.I.N.G.S. code40. Although there are various criteria for ring detection, a primitive method was adopted in this work41.

As the other method to elucidate the atomic configurations of the materials, an analysis based on PH was performed using the HomCloud code30,42. The analysis can extract topological features from three-dimensional atomic configurations, which can be regarded as a point set in three-dimensional space, and the features can be expressed in a two-dimensional format called the persistence diagram (PD). A schematic illustration of the construction of the PD is shown in Fig. S1. A sphere is placed at each atomic position, and the radius is increased from zero to a larger value. The radius that generates a new ring or void (cavity) is called “birth”, and the radius that annihilates this ring or void (cavity) is called “death”. Pairs of birth and death for all pairs are plotted in a two-dimensional graph, i.e., PD. This PD provides information on structural features such as the sizes and shapes of the rings and voids (free spaces) and thus enables us to gain a deep understanding of the atomic configurations. Therefore, in the case of the negative electrode materials of LIBs, the analysis enables us to determine the sizes and shapes (distortions) of possible Li+ conduction pathways. To distinguish rings formed by Ti–O or Nb–O pairs and then visualize their contributions to rings formed by all the atoms, connected PDs were also constructed43. Further details on the PH analysis are described in the literature30,31.

Results and discussion

Materials

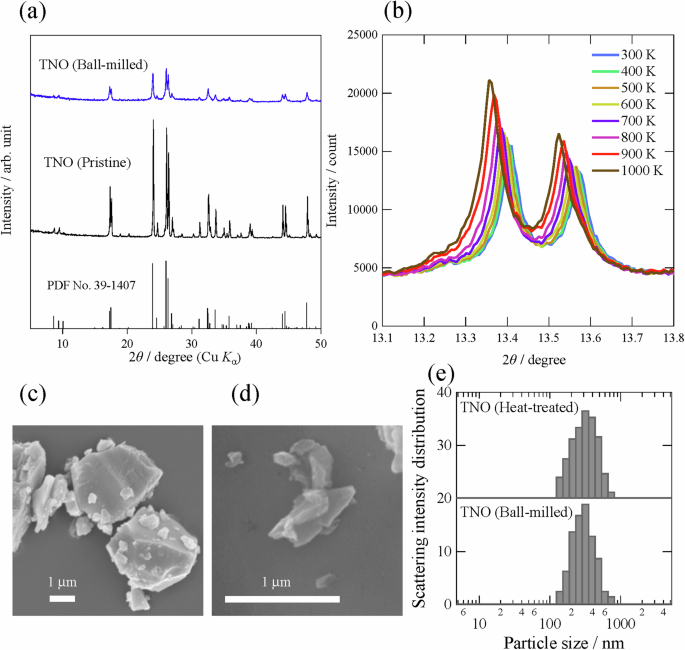

Figure 2a shows the XRD patterns (Cu Kα) of the as-synthesized and ball-milled samples [TNO (Pristine) and TNO (Ball-milled), respectively]. All the peaks in TNO (Pristine) can be attributed to the monoclinic Wadsley–Roth phase (space group, C2/m; Fig. 1)21,22,23,24,25,44, yielding a single phase without any impurities. Although TNO (Ball-milled) can be assigned to the same phase, the Bragg peaks of TNO (Ball-milled) are weaker and broader than those of the pristine sample; this suggests that the crystal structure was disturbed by the ball-milling process. The metal composition ratio evaluated by ICP‒AES was Ti:Nb = 1.026(1):1.973(2), which is almost equal to the nominal composition, i.e., Ti:Nb = 1:2.

a XRD patterns at room temperature (Cu Kα) and (b) those of TNO (Ball-milled) recorded by in situ high-temperature measurements (λ = 0.8 Å). SEM images of (c) TNO (Pristine) and (d) TNO (Ball-milled). e Particle size distributions of TNO (Ball-milled) and TNO (Heat-treated).

For the preparation of samples with a different degree of disorder (order) in the crystal structure, TNO (Ball-milled) was heat-treated at an elevated temperature in this study. To determine the heat-treatment temperature, in situ XRD measurements at high temperatures were preliminarily carried out for TNO (Ball-milled), and the results are shown in Fig. 2b. There is no significant change in the crystal structure regardless of temperature, although the Bragg peaks shift to lower angles with increasing temperature owing to thermal expansion. Notably, a significant increase in the Bragg peak intensity can be observed at approximately 900 K (627 °C), suggesting that the crystallinity of the TNO particles is improved by heat treatment. Based on these results, in this study, TNO (Ball-milled) was heat-treated at 650 °C to investigate the effect of crystallinity on the charge/discharge properties. The structural disorder in the crystal is discussed in more detail later.

The particle morphologies (SEM images) of TNO (Pristine) and TNO (Ball-milled) are shown in Fig. 2c and d, respectively. The particle size is markedly reduced by the ball-milling process. The particle size distributions (Fig. 2e) also revealed that the particle size of TNO (Ball-milled) is approximately 280 nm and is unchanged even after heat treatment at 650 °C; this demonstrates that only the crystallinity (the degree of disorder in the crystal structure) is different between the TNO (Ball-milled) and TNO (Heat-treated) samples.

Figure S2 shows X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra at the Ti K-edge and Nb K-edge of the samples. The Ti K-edge spectra show that the absorption energy of Ti in each sample is close to that of TiO2 and is therefore considered to be tetravalent. The Nb K-edge XANES spectra also indicate that the Nb ion is pentavalent in the samples because the absorption energy at the Nb K-edge of each sample is almost the same as that of Nb2O5. These results suggest that preparation processes, such as ball milling and heat treatment, do not affect the valences of Ti and Nb in the case of TiNb2O7.

Charge/discharge properties

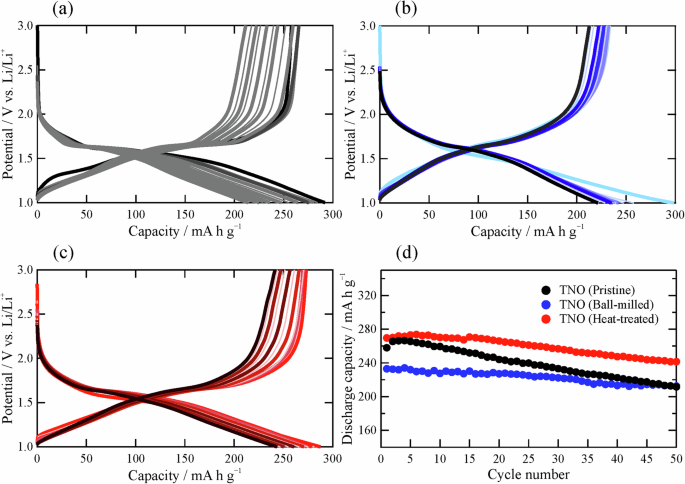

The charge/discharge profiles of TNO prepared by the different processes are shown in Fig. 3a–c, and the cycle performance of the capacity for Li+ deinsertion, which is defined as the discharge capacity, is summarized in Fig. 3d. TNO (Pristine) has an initial discharge capacity of approximately 260 mA h g–1, which is higher than that of a typical oxide-based electrode material, Li4Ti5O126,7,8. However, as the number of cycles increases, the capacity significantly deteriorates. This deterioration in TNO (Pristine) may be due to the large particle size (long Li+ diffusion length), which is not suitable for Li+ insertion and deinsertion. According to the literature23, a smaller particle size tends to improve the electrode properties. However, the initial discharge capacity of TNO (Ball-milled) with a smaller particle size is significantly lower than that of TNO (Pristine), although the capacity retention can be improved by ball milling; this means that electrode properties are affected by factors other than particle size. Notably, TNO (Heat-treated) results in the highest initial discharge capacity of approximately 270 mA h g–1 while maintaining good capacity retention, although the particle size of this sample is essentially the same as that of the ball-milled sample. Therefore, the change in crystallinity (atomic configuration) indicated by the XRD patterns is considered to affect electrode properties.

Charge/discharge profiles of (a) TNO (Pristine), b TNO (Ball-milled), and c TNO (Heat-treated). d Discharge capacities (capacities for Li+ deinsertion) as a function of the number of cycles.

These results indicate that the charge/discharge properties of TiNb2O7 depend significantly on the preparation process and that the significantly disordered atomic configuration manifested in the Bragg peak broadening degrades the discharge capacity. The disordered atomic configuration is quantitatively elucidated based on the average and local structures in the following subsections.

Average structure of the pristine material

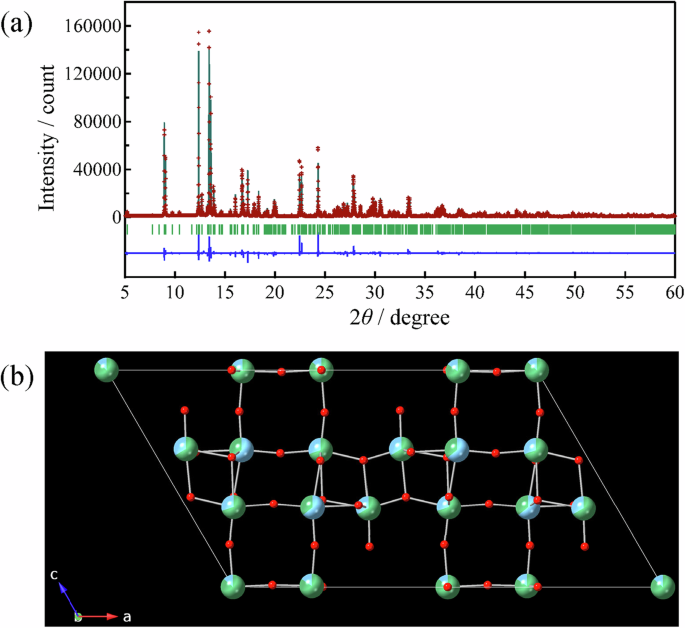

The average structure of TNO (Pristine) was investigated via a Rietveld refinement using the synchrotron XRD pattern. In the analysis, the space group was assumed to be C2/m44, and constraints were imposed so that the metal composition calculated from the site occupancies was equal to that estimated by ICP‒AES. Figure 4 shows the Rietveld refinement pattern, and Table S1 shows the refined structural parameters. As shown in Fig. 4, the average structure was successfully refined under the assumption mentioned above.

a Rietveld refinement pattern (synchrotron X-ray) and b refined structure: blue, Ti; green, Nb; red, O.

Figure 4b shows the refined average structure. This structure consists of five different cation sites, and the cations form octahedra with six oxide anions, for example, (Ti,Nb)1–O6. As summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 1, (Ti,Nb)1–O6 exist at the center of the corner-sharing block and share apex oxygens with other octahedra, whereas the others share some edges with the other octahedra. Notably, the site occupancy of Nb is the greatest at the (Ti, Nb)1 site, and the occupancies at the (Ti,Nb)2 and (Ti,Nb)4 sites are greater than those at the (Ti,Nb)3 and (Ti,Nb)5 sites. Therefore, Nb tends to occupy octahedral sites with fewer shared edges. This may be due to the higher valence of Nb5+ than of Ti4+; i.e., the distances between the cations of the octahedra sharing edges are shorter, and thus, the electrostatic repulsion between the cations is stronger. Table 1 also presents distortions of (Ti,Nb)–O6 octahedra in TNO (Pristine); a larger value of the quadratic elongation represents a larger distribution of bond lengths, and a larger value of the bond angle variance represents a larger distribution of bond angles45. As shown in this table, both the quadratic elongation and bond angle variance are the smallest in (Ti,Nb)1–O6, which exist at the center of the corner-sharing block. As lithium ions are considered to diffuse through this block during charge/discharge processes, as discussed below, such a low distortion is considered desirable for excellent negative electrode properties.

Comparison of local structures

As described above, the Bragg peaks of TiNb2O7 markedly broadened when the sample underwent the ball-milling process, indicating that accurate information on the relationship between the atomic configuration and negative electrode properties cannot be derived only by the average structure analysis using the Bragg peaks. Therefore, in this study, we focused on local structure analysis (an analysis of structures without translational symmetry) using quantum beam total scattering data.

Figure 5 shows the X-ray T(r) of TNO (Pristine), TNO (Ball-milled), and TNO (Heat-treated). For TNO (Pristine), the neutron T(r) is also presented in Fig. S3. In the X-ray T(r) of all the samples, the peak can be observed at approximately 1.9 Å, which can be attributed to the Ti–O and Nb–O bonds within the TiO6 and NbO6 octahedra. The peak intensities are almost identical, suggesting that the shape of the octahedra is not significantly changed by ball milling or heat treatment. Similarly, the peak intensity at approximately 3.3 Å is not considerably affected by the treatments. The peak corresponds to the distance between the cations at the adjacent edge-sharing octahedra, indicating that the change in the edge-sharing part is not significant. Notably, this peak at 3.3 Å is negligible in neutron T(r), as shown in Fig. S3; this is because Ti, with a negative coherent scattering length46 (Table S2), exists predominantly in the edge-sharing region. This result is consistent with the site occupancies obtained via Rietveld refinement (Table 1).

a X-ray T(r) of TNO and b the atomic configuration of TNO.

In contrast to these peaks, the peak intensity at approximately 3.8 Å is markedly decreased by ball milling and increased again by the subsequent heat treatment at 650 °C, as shown in Fig. 5a. Since this distance corresponds to the cation–cation correlation between the centers of the adjacent corner-sharing octahedra, such peak behavior suggests that the structure of the corner-sharing blocks is significantly disturbed by the ball-milling treatment. This result implies that the intermediate-range structure has a significant effect on the negative electrode properties, as in the case of another Wadsley–Roth phase, i.e., Ti2Nb10O2947. However, since the average structure of TNO (Pristine) refined by the Rietveld method cannot reproduce an experimentally obtained neutron G(r), as shown in Fig. S4, the average structure does not provide accurate information on the intermediate-range structure (network structure) forming Li+ conduction pathways.

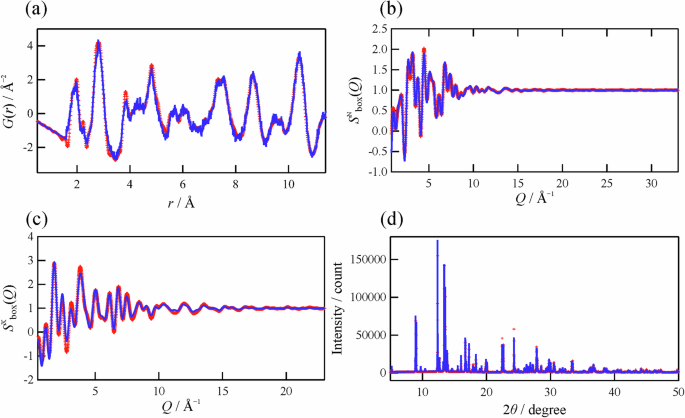

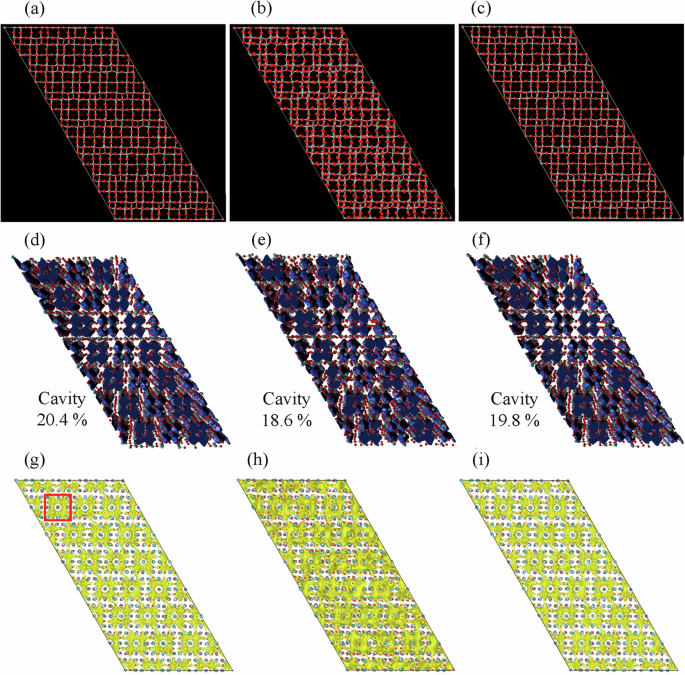

To gain a deeper understanding of the network structure, three-dimensional atomic configurations of the samples were constructed via RMC modeling based on total scattering data. Figure 6 shows neutron G(r), neutron and X-ray Sbox(Q), and the Bragg profile of TNO (Pristine). All the experimental data are well reproduced via RMC modeling. The three-dimensional atomic configurations of TNO (Ball-milled) and TNO (Heat-treated) were also constructed via RMC modeling (Fig. S5). Snapshots of the simulated atomic configurations including 5040 atoms are shown in Fig. 7a–c. Although all the samples have 3 × 3 corner-sharing blocks terminated by edge-sharing regions, the atomic positions are apparently disturbed in the ball-milled sample, as shown in Fig. 7b. This disordered atomic configuration is considered one of the reasons for the low discharge capacity of TNO (Ball-milled). Thus, we analyzed these atomic configurations quantitatively, with a particular focus on the network structure.

a Neutron G(r), b neutron and c X-ray Sbox(Q), and d Bragg profile. The red plus marks and the blue line represent the experiment and RMC model, respectively.

Snapshots of the atomic configurations of (a) TNO (Pristine), b TNO (Ball-milled), and c TNO (Heat-treated). Surface-based cavities of (d) TNO (Pristine), e TNO (Ball-milled), and f TNO (Heat-treated). BVS mappings with BVS = 0.7 − 1.3 of (g) TNO (Pristine), h TNO (Ball-milled), and i TNO (Heat-treated). The mappings were visualized via the VESTA program48. The red square in (g) represents one of the corner-sharing blocks.

Effect of the preparation process on topology

In Wadsley–Roth phase TiNb2O7, lithium ions are considered to diffuse through cavities formed by the ring structures of the corner-sharing blocks. To confirm this, we performed cavity analysis with a cutoff distance of 2.5 Å and estimated the possible Li+ positions via the BVS mapping technique. Figure 7d–i shows the results of the analysis using the atomic configurations obtained via RMC modeling. Large cavities are found in the corner-sharing blocks, and Li+ can exist at the cavities in all the samples. Although the cavity volume is almost the same among the samples, the cavities for Li+ diffusion seem to be disturbed considerably in TNO (Ball-milled), as shown by the BVS mappings. Such a cavity disturbance might be one of the reasons for the low discharge capacity of the ball-milled sample (Fig. 3). Therefore, to study the Li+ diffusion pathways in detail, we focused on the ring structures in the samples. A conventional ring analysis was performed on the RMC configurations with the definition of the primitive ring assuming a 1st coordination distance of rM–O = 2.85 Å. Fig. S6 shows the ring size distributions and examples of the corresponding ring structures. As shown in this figure, the ring size distribution is hardly changed by ball milling and heat treatment, and all the samples have twofold rings (Fig. S6d) and threefold rings (Fig. S6e) in the edge-sharing regions, and flat fourfold rings (Fig. S6f) in the corner-sharing blocks. A small fraction of rings larger than the fourfold rings were also detected owing to the low symmetry in the crystal structure: these rings are bent at almost 90°, as shown in Fig. S6g. Considering the Li+ conduction pathways (for example, as presented in Fig. 7), only the flat fourfold rings shown in Fig. S6f may provide spaces for Li+ diffusion. Accordingly, the shape, not the number of rings, is closely related to the insertion and deinsertion of lithium ions during charging and discharging, respectively.

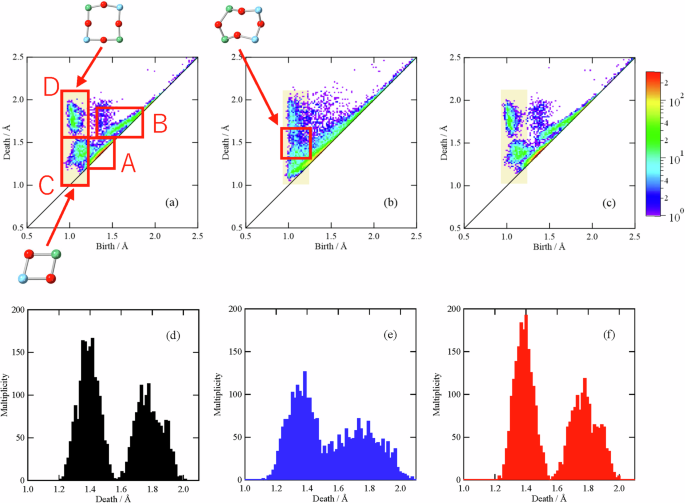

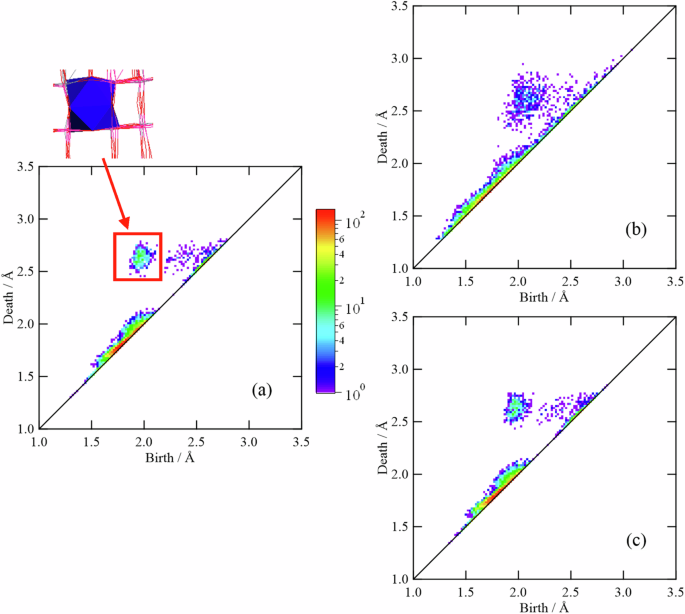

To quantitatively elucidate the shape of the network structure consisting of rings, we performed persistent homology analysis. Figure 8 shows the one-dimensional PD (PD1) of the three TNO samples. The PD1 of TNO (Heat-treated) with the best charge/discharge properties is similar to that of TNO (Pristine), whereas the PD1 of TNO (Ball-milled) with low discharge capacity is apparently distributed. These results indicate that the atomic configuration is disturbed by the ball-milling process.

Persistence diagrams (PDs) for (a) TNO (Pristine), b TNO (Ball-milled), and c TNO (Heat-treated). The profiles associated with the areas highlighted in orange, corresponding to Groups C and D, are plotted for (d) TNO (Pristine), e TNO (Ball-milled), and f TNO (Heat-treated).

The PD1s of the TNO samples can be divided into four groups, as shown in Fig. 8a, and the structural characteristics, from which each group originated, are extracted via inverse analysis. A small birth region close to the diagonal line (Group A) originates from small triangles consisting of a cation and two oxygen atoms. The triangle is formed by the central cation and two apex oxygens in TiO6 or NbO6. A relatively large birth region close to the diagonal line (Group B) could be assigned to triangles consisting of three oxygens within TiO6 or NbO6. Therefore, the profiles in the vicinity of the diagonal line do not provide any information on Li+ conduction pathways because they have a short lifetime and stem from short-range structural units such as TiO6 or NbO6.

We also performed inverse analysis focusing on the other groups located away from the diagonal line. The profile observed at a birth value of approximately 1.1 Å and a death value of approximately 1.4 Å (Group C) mainly originates from twofold and threefold rings. In other words, the profile is considered to reflect the ring shapes in the edge-sharing parts in the Wadsley–Roth phase; this means that the cavity represented by the small death value of approximately 1.4 Å should be too narrow for lithium ions to conduct. Thus, the profile of this group is unlikely to account for the electrode properties of TNO.

The profile observed at a birth value of approximately 1 Å and a death value of approximately 1.8 Å (Group D) originates from rings of fourfold or larger sizes. In addition, there is no correlation between the ring size and the birth/death ratio, indicating that rings larger than fourfold are in a folded form, as mentioned above (Fig. S6g). Therefore, only the flat fourfold ring with a large free area is considered to be closely related to the Li+ conduction pathway. To investigate the cation species contributing the fourfold rings, Ti- and O-centric PD1s and Nb- and O-centric PD1s were investigated and compared with PD1s composed of all atoms; the results are shown in Fig. S7 as connected PD1s. In this figure, the upper left of the diagonal line represents PD1 considering all the atoms, which is essentially the same as that in Fig. 8a–c. The bottom right of the diagonal line is the Ti- and O-centric PD1 or Nb- and O-centric PD1. For the reader’s convenience, these PD1s are plotted inverted against the diagonal line. The yellow lines in the connected PD1 represent the correlations. In the case of the Nb- and O-centric PD1s that are inverted about the diagonal line (Fig. S7d–f), their profiles are similar to those of the PD1 consisting of all the atoms, suggesting that the rings consisting of Nb and O contribute almost equally to the rings consisting of all the atoms in TiNb2O7. However, the distribution of the Ti- and O-centric PD1s is different from that of the PD1s considering all the atoms (Fig. S7a–c). As emphasized in Fig. S7a, the rings consisting only of Ti and O can hardly form the rings belonging to Group D. In other words, most of the rings in Group D contain Nb, and the rings in Group D have changed to rings with larger birth values when only Ti and O are considered, as indicated in Fig. S7g. These results demonstrate that it is difficult for fourfold rings, which constitute a conduction pathway for Li+, to be formed only by Ti and O. This corresponds to the high Nb occupancy in the (Ti,Nb)1 site belonging to the fourfold rings (Table 1).

To elucidate the effects of ball milling and heat treatment on the shapes of the rings in Group D, the distributions of the birth and death values for the three TNO samples were examined and are shown in Fig. 8d–f. These profiles were generated considering the plots of areas with birth values of 0.95–1.25 Å and death values of 1.0–2.1 Å, i.e., the peak at a smaller death value represents the rings of Group C, and the peak at a larger death value represents the rings of Group D. Clearly, the ball-milling process broadens these peaks, particularly the peak at a larger death value, considering the fitting results of the profiles (Fig. S8 and Table S3). This tendency suggests that the rings in the ball-milled sample have a large distribution in shape and/or size. The inverse analysis of the plots of the boundary region between Groups C and D (Fig. 8b) revealed that the broadening of the peaks after the ball-milling process was caused by considerable distortion of the rings, especially the fourfold rings. However, the subsequent heat treatment reduces the distribution, as shown in Fig. 8f, indicating that the ring shape essentially returns to the pristine state. As previously mentioned, one of the factors contributing to the low discharge capacity of TNO (Ball-milled) is the disordering of the crystal structure manifested by the broadening of the Bragg peaks. The topological analysis demonstrats that the disordering is caused mainly by the change in the shape of the fourfold rings in the corner-sharing blocks, which form the Li+ conduction pathways.

Figure 9 shows the two-dimensional PD (PD2), which captures the shapes of the cavities (free spaces) in the three TNO samples. In this figure, the profiles in a red rectangle represent cubic cavities without apex cations in the corner-sharing blocks, and the cavities are significantly disturbed by the ball-milling process. Since these cavities form Li+ conduction pathways, PD2 and PD1 indicate disturbed conduction pathways in TNO (Ball-milled).

Persistence diagrams (PDs) for (a) TNO (Pristine), (b) TNO (Ball-milled), and (c) TNO (Heat-treated).

From the analytical results described above, it can be concluded that the Li+ conduction pathway with less distortion results in better negative electrode properties: The highest charge/discharge capacities can be achieved not by simply reducing the particle size via ball milling but by relaxing the distortion in the network consisting of TiO6 and NbO6 with subsequent heat treatment while keeping the particle size small. The result also indicates that the topology can be controlled by optimizing the preparation process. Since this finding cannot be obtained only by conventional average structure analysis based on Bragg peaks, it has been demonstrated for the first time that the combination of intermediate-range structure and topology analyses is a very promising way to develop guidelines for improving electrode properties.

Responses