Mussel-inspired thermo-switchable underwater adhesive based on a Janus hydrogel

Introduction

Underwater adhesives enable the bonding of materials in biological environments, thereby facilitating functions such as hemostasis and the adhesion of tissues and biomedical devices1,2,3. Particularly, a stable connection between bioelectronics and biointerfaces is important for obtaining information about the state of health by monitoring the biological information transmitted from organs, such as electrocardiograms (ECGs), and to provide efficient treatment and drug administration by emitting electricity from devices4,5,6. Because biomedical devices are exposed to moisture in the human body, appropriate underwater adhesives are necessary to connect the devices to tissues7,8. In addition, sufficient adhesive strength is required to attach biomedical devices to solid and wet substrates, and most glues must be dried for sufficient adhesion between the tissue and the substrate. Although strong adhesion enables stable interconnections in biomedical devices, it can cause severe tissue damage upon detachment. Safe detachment of the adhesive is essential for the repositioning and retrieval of biomedical devices. Consequently, maintaining strong adhesion in wet environments while enabling gentle detachment remains a challenge9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

Impressive adhesive properties are found in nature; therefore, nature-inspired adhesives have significant potential for use in medical and industrial applications2,16,17,18,19,20. In addition, underwater adhesives inspired by natural organisms, such as Dytiscus lapponicus21, octopi22, frogs23, barnacles18, and clingfish24, are promising candidates as reversible adhesives. These organisms have been investigated to better understand their adhesion and detachment abilities. For example, mussels exhibit robust underwater adhesion originating from adhesive proteins, which enables them to adhere to various substrates in marine environments25,26,27. The catechol group is highly concentrated in the mussel foot and exhibits underwater adhesion via strong interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, metal-coordination bonds, and hydrophobic interactions28,29,30. Recently, it has been revealed that mussels not only possess underwater adhesive capabilities but also exhibit reversible detachment triggered by environmental stress31. The mussel byssus stem is connected to the body and adhesive portion via a mechanical connection of numerous motile epithelial cilia. However, the connection is weakened by a stimulus, which causes the mussel body to detach and move away, thus leaving the foot to adhere to the surface. The complex detachment mechanism of mussels enables strong adhesion and peeling with minimal damage to the body and adhesive substrate. Mussel-inspired glues that contain catechol and its derivatives have attracted significant attention owing to their remarkable adhesive properties, particularly their ability to adhere to various surfaces in underwater environments29,30,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. Several catechol-based stimuli-responsive adhesives have been previously reported42,43; however, adhesives with a large gap in adhesion strength hinder on-demand adhesion.

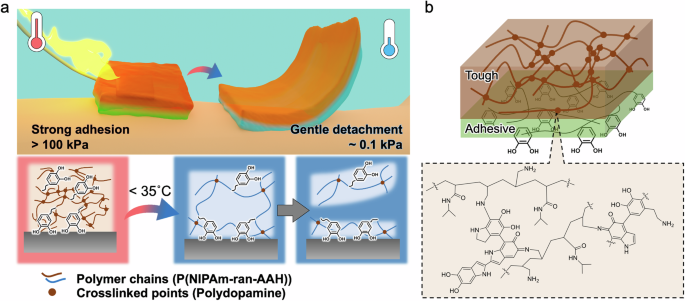

In this study, mussel-inspired stimuli-responsive adhesive hydrogels were designed using thermoresponsive polymers and adhesive molecules to address minimally invasive on-demand peeling (Fig. 1a). By combining N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPAm) and dopamine, a thermoresponsive adhesive (TSA) hydrogel with a Janus structure achieved thermoresponsive and underwater adhesion. Dopamine incorporated with catechol and its components strongly adhered to various surfaces, including wet surfaces. NIPAm enables the hydrogel to be thermoswitchable at body temperatures while providing a significant improvement in mechanical and adhesion strength owing to its lower critical solution temperature (LCST). Notably, the hydrogel was fabricated via interfacial polymerization at an air/solution interface to obtain Janus features with a gradient mechanical strength and to improve the operability of the TSA hydrogels (Fig. 1b)44,45,46,47,48. The lowermost surface of the hydrogel had a low crosslinking density, and the freely movable catechol molecules enabled the hydrogel to adhere to the substrates. When the hydrogel was heated above the LCST, it became tough and formed strong bonds with the substrate. In contrast, the bottom surface of the hydrogel became sufficiently soft below the LCST and gently detached from the surface via cohesive failure. The TSA hydrogel exhibited over 1000-fold stronger adhesion at high temperatures than at low temperatures and gentle detachment from the surface at low temperatures. Furthermore, the electrode-embedded TSA hydrogel adhered to a human arm above the LCST, and continuous electrical signals were monitored for 10 min. Thus, the TSA hydrogel could serve as an effective adhesive to securely attach bioelectronic devices to the human body and minimize skin damage upon removal by simply controlling the temperature.

a Schematic of the TSA hydrogel with strong thermoswitchable adhesion and gentle detachment. Dopamine and NIPAm in the TSA hydrogel enable reliable underwater adhesion and thermoswitchability at body temperatures, respectively. b Schematic of the Janus structures of the TSA hydrogel with tough and adhesive parts (top). Possible chemical structure of the TSA hydrogel via air-oxidation and crosslinking reactions (bottom).

Results and discussion

Design of the TSA hydrogel

To induce a significant gap in adhesive strength, the toughness of the hydrogel must undergo substantial changes between high temperatures and low temperatures. Particularly challenging is the low mechanical strength exhibited at lower temperatures, which compromises the handling of the hydrogel. In this study, hydrogels with Janus structures were used to resolve this issue. A TSA hydrogel with a Janus structure was synthesized from dopamine and an amine-containing polymer via oxygen-assisted interfacial polymerization (Fig. 1b and Scheme S1). Oxygen-assisted interfacial polymerization can easily yield tough and thick hydrogel films and change the size of the hydrogel by controlling the diffusion of oxygen44,47,49. Furthermore, the TSA hydrogel exhibited Janus properties owing to the diffusion of oxygen (Fig. 2a). The air side of the hydrogel was densely crosslinked with oxidized dopamine and a thermoresponsive polymer, which increased the mechanical strength and operability. The solution side of the hydrogel was loosely crosslinked, and flexible and movable adhesion molecules at the surface functioned as the adhesive layer. The TSA hydrogel primarily comprises three monomers: NIPAm, allylamine hydrochloride (AAH), and dopamine. The amine-containing polymer was synthesized via the polymerization of NIPAm and AAH (P(NIPAm-ran-AAH)). PNIPAm has a LCST and provides thermoswitchability to the hydrogels, and the AAH in the copolymer functions as a crosslinking point during hydrogel formation. Dopamine functions as both a crosslinker of P(NIPAm-ran-AAH) and an adhesive owing to the unique adhesive properties of its catechol group. Oxygen reacts with dopamine to form dopaquinone, which further reacts with dopamine and amines in the amine-containing copolymers, resulting in the formation of polydopamine50,51,52 and crosslinking reactions (Scheme S1)53,54.

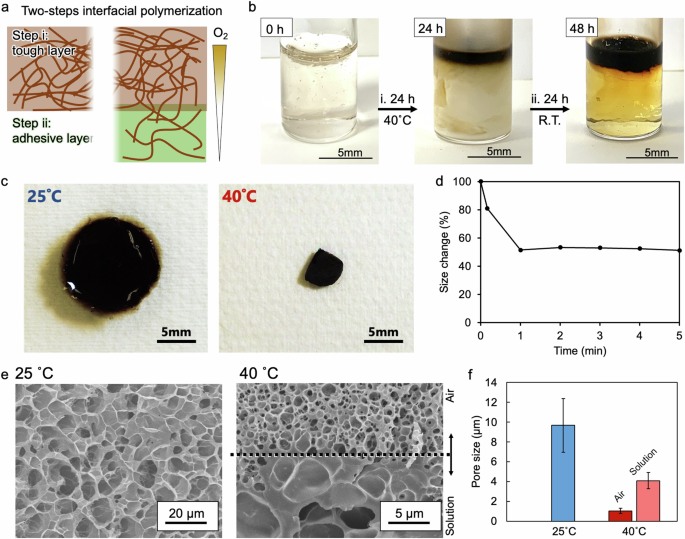

a Images and b photographs of the solution before and after oxygen-assisted interfacial polymerization at different steps. Step i: The solution became entirely white due to the sol‒gel transition, and only the top of the sample became brown. Step ii: Air-oxidation step at room temperature. c Images of the hydrogel at 25 and 40 °C. The hydrogel pieces were cut with a round punch (15 mm in diameter) at 25 ° C. d Size change over time. e Cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the hydrogels. The hydrogels that swelled in water at 25 and 40 °C were frozen with liquid nitrogen and dried under vacuum. f Average pore sizes of the freeze-dried hydrogels. Because different pore structures were observed at the air and solution sides for the hydrogel frozen at 40 °C, both pore sizes were divided into “Air” and “Solution”.

Since the hydration layer on the substrate hinders the interaction between the adhesive and the substrate, the hydration layer must be removed to ensure adhesion to the substrate in an underwater environment41,55. The hydrophobicity of the PNIPAm in the TSA hydrogel promoted the removal of the hydration layer, resulting in an improvement in the interaction between the adhesive and the substrate.

The adhesion strength can be controlled not only by the joint strength between the substrate and the hydrogel but also by the toughness of the adhesives. In the hydrophobic state of PNIPAm (>LCST), hydrophilic molecules, such as allylamine and catechol, are excluded from the outside of the hydrogel, and the toughness of the TSA hydrogel is improved, resulting in its increased adhesive strength (Fig. 1a). In contrast, by cooling to temperatures below the LCST, PNIPAm becomes hydrophilic, and the toughness of the hydrogel decreases, which enables cohesive failure near the surface and results in poor adhesion strength28,56. Therefore, the Janus hydrogel could be easily detached from the surface below the LCST, even though the catechol groups remained bonded to the surface.

Synthesis of the thermoresponsive copolymer with an amine group

The transmittance of the solution was measured at different temperatures to investigate the temperature responsiveness of the synthesized copolymers (Fig. S1a). At allylamine concentrations of 0.5% and 1%, turbidity was observed at temperatures greater than 35 °C. This result indicated that the polymer reached its LCST, causing hydrophobic interactions and polymer aggregation, thereby resulting in light scattering and the loss of liquidity (Figure S1b). Further increasing the allylamine concentration to 5% and 10% shifted the temperature at which turbidity occurred to higher temperatures. This decrease in temperature sensitivity could be attributed to an increase in the number of hydrophilic functional groups. While a higher concentration of allylamine resulted in more crosslinking points and, thus, a more robust gel, a decrease in temperature responsiveness also occurred. Therefore, the increased LCST was attributed to the hydrophilic contribution of the amine groups. In subsequent experiments, the concentration of allylamine was fixed at 1%.

Synthesis of the TSA hydrogel

The TSA hydrogel was synthesized via oxygen-assisted interfacial polymerization at an air/liquid interface (Fig. 2a). By resting a mixture of dopamine- and amine-containing polymers at room temperature, a brown composite film formed at the air/liquid interface. However, the resulting composite film lacked sufficient strength because it stretched and broke easily when lifted with tweezers (Fig. S2). When the mixture rested and reacted in solution, the oxidation and crosslinking reactions of dopamine occurred at the air/liquid interface. However, the oxidized dopamine diffused into the solution via physical convection simultaneously with these reactions, resulting in insufficient crosslinking reactions at the interface and significantly poor toughness of the films.

The hydrogel film, synthesized via the interfacial polymerization of polydopamine and amine-containing polymers, was promoted in the gel state because the dopamine that was oxidized by oxygen from the air crosslinked with the copolymer and remained near the air side, thus enabling more crosslinked points than those formed in the sol state49. Therefore, interfacial polymerization was performed in the gel state to increase the toughness of the hydrogel sufficiently (Step i in Fig. 2b). The solution was entirely gelled and lost fluidity at temperatures above the LCST owing to the physical crosslinking of hydrophobic PNIPAm in the solution (Fig. S1b). In this study, the second step of the interfacial crosslinking reaction was performed at room temperature (i.e., in the sol state) for 24 h to utilize the loosely gelled portion as an adhesive layer (Step ii in Fig. 2b). Under the conditions created in the gel state, only the upper part of the reaction mixture was brown, whereas the lower part was slightly yellow. The distinct separation of layers suggested that only oxygen diffusion and dopamine oxidation reactions were affected and that convection was sufficiently suppressed. The Janus hydrogel was moderately strong and could be lifted with tweezers; thus, it was easier to handle than the gels made at room temperature via a single-step process. The obtained TSA hydrogel was characterized via UV‒vis (Fig. S3) and Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopies (Fig. S4), which confirmed that PNIPAm and polydopamine were present in the TSA hydrogels.

The hydrogel immediately contracted upon exposure to a high temperature of 40 °C, shrinking to approximately 50% of its original diameter within 1 min, and then remaining consistent in size (Fig. 2c, d). Shrinking enabled the densification of the hydrogel and increased its toughness. Furthermore, when the hydrogel returned to room temperature, it swelled to its original size, and repeated temperature changes resulted in repeated swelling and contraction (Fig. S5). These results demonstrated that the temperature responsiveness of the hydrogel was maintained even after dopamine crosslinking. Quantitative cytocompatibility tests of fibroblasts were performed (Fig. S6). The cells were cultured in a medium supplemented with TSA hydrogels at 37 °C for 3 days, and the results revealed that the TSA hydrogels had good cell viability.

The cross-sectional structures of the TSA hydrogels were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) following freeze-drying (Fig. 2e). To observe the micropore structures in the TSA hydrogels, they were swelled in water at 25 and 40 °C, frozen with liquid nitrogen, and dried under vacuum. The hydrogels that swelled at 25 °C had similar pore sizes (9.7 µm) that were larger than those of the hydrogels that swelled at 40 °C (Fig. 2f). Notably, a border of different pore sizes was clearly observed in the middle of the TSA hydrogel that swelled at 40 °C, and the air side had a smaller pore size (1.0 µm) than did the solution side (4.1 µm). This difference in pore size at the interfaces was probably caused by oxygen diffusion from the air side to the solution side and the different crosslinking densities45,46,47. Therefore, different crosslinking densities resulted in Janus features of various porous structures and mechanical strengths.

Evaluation of the adhesive ability

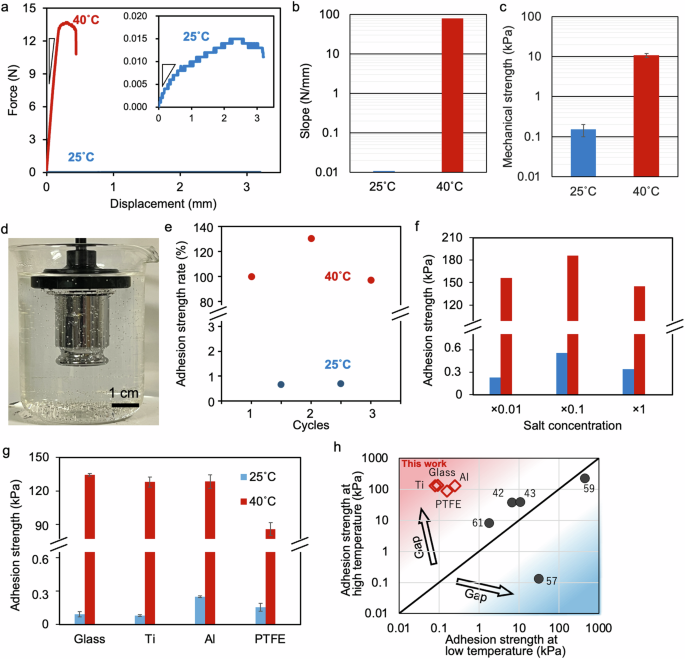

The prepared hydrogel adhered to a glass substrate in water, and the adhesion strength was measured via a tensile machine (Fig. 3a). Measurements were conducted inside a glass beaker with the hot plate, glass beaker, and substrate securely attached with double-sided tape. The adhesive hydrogel was inserted between the substrates, and the tensile strength was measured by lifting the top substrate. Because the solution side of the hydrogel exhibited better adhesion to the substrate than did the air side, the hydrogel was folded such that the top and bottom surfaces faced the solution side of the TSA hydrogel. When the hydrogel was heated to 40 °C (>LCST), its adhesive strength reached approximately 14 N (red line in Fig. 3a). To gently detach the adhesive hydrogel from the surface, it must be sufficiently softened and broken quicker than the substrate or interfacial bonding. By decreasing the temperature below the LCST, the Janus hydrogel gradually detached from the glass substrate, with an adhesive strength of approximately 0.015 N (blue line in Fig. 3a). This result demonstrated an approximately 1000 times weaker adhesive ability than the high-temperature condition and enabled gentle detachment from the surface. Notably, the slope of the relationship between the displacement and adhesive strength was approximately 7000 times steeper at high temperatures than at low temperatures (Fig. 3b). This dramatic change in slope indicated an increase in the mechanical strength of the hydrogel57, which also increased the adhesive strength. In contrast, the mechanical strength of the bulk hydrogels was lower at different temperatures (approximately 70 times greater) than the slope and adhesive strength (Fig. 3c). The mechanical strength reflected the bulk properties of the Janus hydrogel, which supported sufficient toughness for handling the hydrogel. In particular, the tough layer had dense crosslinks and high strength, which likely explained the smaller gap. Therefore, the significant difference in the adhesive strength of the TSA hydrogel was probably attributed to changes in the mechanical strength of the hydrogel near the adhesive surface. The adhesive gel continuously held a 100 g weight attached to a glass substrate in water (Fig. 3d). When the adhered substrate was cooled to low temperatures (25 °C), the adhesive strength significantly decreased, enabling easy removal. This significant increase and decrease in adhesive strength with temperature variation indicated the reversible response of the hydrogel (Fig. 3e). Therefore, this hydrogel, which exhibited strong adhesion under submerged conditions, needed minimal tensile force for detachment.

a Representative underwater adhesion strength curves of the hydrogel on glass plates (1 × 1 cm2) at 40 and 25 °C. The inset image is a magnified adhesion curve at 25 °C. b Slopes during the peeling tests shown in a of the TSA hydrogel at 25 °C (blue) and 40 °C (red). c Mechanical strength of the bulk hydrogel at 25 °C (blue) and 40 °C (red). d Underwater adhesion to glass plates with a 100 g weight. e Repeatability of the underwater adhesion of the hydrogel to glass plates with changes in temperature. f Effects of different salt concentrations (Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline) on the adhesion strength. g Adhesion strength of the hydrogel to glass, Ti, Al, and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) plates at 25 °C (blue) and 40 °C (red). h Comparison of the adhesion strengths of reported thermoresponsive hydrogels at low and high temperatures. The inserted numbers indicate refs. 42,43,57,59,61.

To demonstrate the biological conditions, the adhesion properties were evaluated over a wide range of salt concentrations, from low concentrations close to those of pure water to concentrations exceeding those found in the biological environment (Fig. 3f). Regardless of the salt concentration, the Janus hydrogel strongly adhered to the glass substrate at high temperatures and easily detached at low temperatures while maintaining its switching behavior. In environments with high salt concentrations, the electrostatic properties of the hydrogel change and might affect adhesion. However, the adhesion properties were not affected by the electrostatic effect of the high salt concentration and exhibited the same adhesion as the low salt concentration, indicating that the TSA hydrogel was based on the hydrogen bonding of catechol. The adhesion properties of different solid substrates were also investigated (Fig. 3g). The adhesion forces between the hydrogel and the aluminum substrate were 0.25 and 130 kPa at low temperatures and high temperatures, respectively. Similarly, the adhesion forces between the hydrogel and the titanium substrate were 0.080 and 128 kPa at low temperatures and high temperatures, respectively. Dramatic changes in adhesion strength, with a 1600-fold difference, between substrates were also observed. This strong adhesion could be attributed to hydrogen bonding between the hydroxyl groups present on the metal and glass surfaces, and the catechol groups present in the hydrogel. The excellent adhesion properties of medical device materials, such as titanium, suggest their potential applications in the healthcare field. Furthermore, the adhesive hydrogel exhibited temperature switching on the surface of a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) substrate because the catechol groups have universal adhesion properties that adhere even to substrates with low surface energy58. Compared with previously reported adhesives, the TSA hydrogel exhibited greater responsivity to temperature (Fig. 3h and Table S1). While some previously reported thermoresponsive adhesives exhibit adhesion at low temperatures57,59, the developed hydrogel exhibits adhesion at high temperatures, enabling the adhesion of materials above or near body temperature. The thermoswitchability of the TSA hydrogel enabled robust adhesion and gentle detachment via temperature modulation, offering significant potential for biomedical applications characterized by minimally invasive procedures.

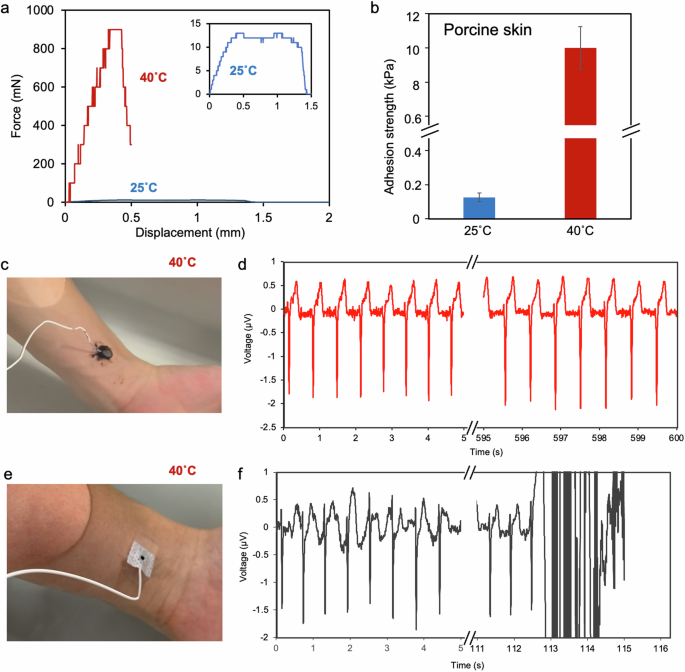

Monitoring electric signals from the human body underwater

The adhesion of the TSA hydrogel to the surface of the skin was investigated. The extracted porcine skin sections were placed between the upper fixture and the lower fixture of a tensile machine, with the hydrogel inserted between them, to evaluate the adhesion of the TSA hydrogel. At low temperatures, the Janus hydrogel gradually detached from the porcine skin (inset graph in Fig. 4a). In contrast, at high temperatures, the adhesion strength rapidly increased with increasing displacement, reaching approximately 900 mN (Fig. 4a). At low temperatures (25 °C), the adhesion strength was 0.1 kPa, but it increased to 10 kPa when heated to 40 °C, demonstrating a 100-fold increase in strength (Fig. 4b). The adhesion strength of the TSA hydrogels at high temperatures was suitable for use in small implants and wearable devices. Biological surfaces have hydroxyl and various functional groups, including amino groups, which enable adhesion via hydrogen bonding with catechol groups and amine–benzene interactions60. However, because porcine skin probably has a lower density of these functional groups than metal surfaces do, the adhesive strength was relatively weaker.

a Underwater adhesion strength–displacement curves of the hydrogel on porcine skin. b Adhesion strength of the hydrogel on porcine skin. c Image of the hydrogel with an embedded carbon electrode on human skin and d ECG monitoring at 40 °C. e Image of a commercial hydrogel electrode on human skin and f ECG monitoring at 40 °C. The electrode detached from the skin after approximately 113 s, and monitoring failed.

Next, a hydrogel electrode was fabricated by embedding a carbon electrode in the TSA hydrogel and adhering it to the surface of the skin in 40 °C water to measure heartbeats. Large changes may induce damage to devices. In this study, carbon felt-based flexible electrodes were employed to minimize damage caused by changes in the size of the hydrogels. The measurement electrode was positioned at the air/liquid interface and then incorporated into the gel during interfacial gel formation to create an integrated gel–electrode device (Fig. S7a). Peel tests were performed by placing the porcine skin under the wiring of the gel electrodes and pulling. The adhesion strength was approximately 0.1 kPa at low temperatures; however, the adhesion strength increased to 0.6 kPa upon heating, demonstrating that the hydrogel maintained temperature responsiveness even when incorporated into the device (Fig. S7b).

The hydrogel electrode was attached to human skin in hot water (40 °C) and connected to cardiogram monitoring instruments. The fabricated gel electrode was continuously measured for more than 10 min in water without delamination (Fig. 4c, d). After the measurement, the electrode-embedded hydrogel was successfully and gently detached from the skin by cooling to a temperature below the LCST. The commercial gel electrodes used for heart rate monitoring quickly absorbed water and detached from the skin within a few minutes (Fig. 4e, f). Thermoresponsive polymers increase the adhesion strength via hydrophobic interactions. However, this process also causes the release of water from the gel matrix, which can disrupt the contact between the electrode and the external aqueous solution. The measurements obtained with this electrode were successful without complications, which could be attributed to the ability of the hydrophilic molecules, such as amines and dopamine, present within the hydrophobic gel to create pathways for water, thereby facilitating electrical connectivity.

Conclusion

TSA hydrogels were synthesized using NIPAm and dopamine and exhibited significant changes in underwater adhesive strength with temperature. The TSA hydrogel was prepared via interfacial polymerization at the air/liquid interface and exhibited Janus features to enhance its mechanical strength and operability. The adhesive force between the hydrogel and solid substrates, such as glass, Ti, and Al, was approximately 130 kPa at temperatures above the LCST. Furthermore, the adhesive hydrogels could be easily peeled off the surface at temperatures lower than the LCST with a much lower strength (~0.2 kPa). The thermoswitchability of the TSA hydrogel was confirmed ex vivo via porcine skin, although the hydrogels were embedded in electrodes. The electrode-embedded TSA hydrogel remained on human skin above the LCST, and continuous electrical signals were monitored for 10 min. In contrast, the commercial hydrogel quickly swelled and detached from the skin, thereby preventing continuous monitoring. The developed hydrogel promises strong adhesion and mild detachment from the substrate via a feasible temperature change, which can contribute to on-demand biomedical applications, such as bioelectric signal monitoring and minimally invasive wound healing.

Experimental section/methods

Chemicals

Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAm), ammonium peroxodisulfate solution (APS), N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), and phosphate-buffered saline were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals (Japan). Dopamine was purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich (USA), and allylamine hydrochloride (AAH) was obtained from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Japan).

Preparation of P(NIPAm-ran-AAH)

To synthesize the 1% amine-containing polymer (P(NIPAm-ran-AAH)), 70 mmol of NIPAm and 0.7 mmol of AAH were added to pure water in an ice bath. The mixture was purged with nitrogen for 15 min, and APS and TEMED were added to initiate free-radical polymerization. After stirring at 25 °C for 24 h, the polymer mixture in cold water as a good solvent was reprecipitated in hot water at 80 °C as a poor solvent several times to ensure the removal of the unreacted monomers and radical initiators. The mixture was placed in a vacuum oven at 40 °C overnight to remove the residual solvents. The obtained copolymer was analyzed by 1H NMR (Fig. S8). The ratio of AAH in the copolymer was adjusted by changing the amount of the AAH monomer.

Preparation of the TSA hydrogel

Dopamine (10 mg mL−1) and P(NIPAm-ran-AAH) (100 mg mL−1) were added to 1.5 mL microtubes (diameter: 9 mm), 2 mL vials (diameter: approximately 10 mL) or 10 mL vials (diameter: approximately 20 mm), and then dissolved in a Tris-HCl solution (pH 8.9). The mixture was incubated at 40 °C for 24 h (Step i in Fig. 2) and then at room temperature for 24 h (Step ii in Fig. 2). The resulting film that appeared at the air‒liquid interface was removed via tweezers and immersed in pure water at room temperature for 24 h. The temperature and relative humidity (RH) of the experimental room were maintained at approximately 25 °C and from 30 to 70% RH, respectively.

Characterization of the TSA hydrogel

The hydrogel was freeze-dried and sputtered with platinum for structural observation via field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; SU-70, Hitachi High-Tech, Japan). The chemical properties of the hydrogels were assessed via FT-IR (Nicolet6700, Thermo Fisher, USA) and UV‒vis spectroscopies (SEC2020 spectrometer, BAS, Japan). The hydrogels were clamped with jigs, and their mechanical strength was measured via a force gauge at different temperatures (ZTA-5N and ZTA-200N, IMADA, Japan).

Evaluation of cytocompatibility

TSA hydrogels were rinsed with 1× PBS 3 times. TSA hydrogels (approximately 8 mm3) were added to 24-well plates supplemented with mouse fibroblasts (4.7 × 104 cells/cm2) (n = 4). The samples were incubated for 3 days at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cell viability was assessed with a Calcein-AM/PI Double Staining Kit (DOJINDO, Japan). Live cells were stained with calcein-AM, which emits green fluorescence, and dead cells were stained with PI, which emits red fluorescence.

Adhesion test

The adhesion strengths of the hydrogels in water at 25 and 40 °C were measured via a force gauge (ZTA-5N and ZTA-200N, IMADA, Japan, respectively). The top substrate and bottom substrate were fixed to a circular flat jig and the center of the bottom of the beaker, respectively, via commercial adhesive tape. Pure water was poured into the beaker to create a wet environment. The hydrogel was placed between the substrates, and the solution temperature was increased to 40 °C via a heater. After the hydrogel was pressed by the two substrates for 10 min, the top substrate was lifted using a tensile testing machine (EMX-1000N-FA, IMADA, Japan), and the adhesion strength was measured via a force gauge with a change in displacement. For the underwater adhesion test at 25 °C, following 10 min of compression at 40 °C, the adhesive hydrogel was exposed to water at 25 °C for 1 h, and a tensile testing machine was used to lift the top substrate and measure the adhesive strength. The results were analyzed via commercial software (Force Recorder Professional, IMADA, Japan).

Monitoring ECG

The carbon electrode was fabricated by attaching a wire to a circular carbon cloth (8 mm in diameter) using carbon paste and applying silicone on top. The carbon electrode was placed near the air/liquid interface of the hydrogel precursor solution for 24 hours at 40 °C and then at room temperature. The hydrogel encapsulated in the carbon electrode was removed via tweezers, and the electrode was immersed in pure water at room temperature for 24 h. ECGs were recorded via commercial ECG electrodes (NM-31; Nihon Kohden Co.), and the prepared adhesive hydrogel electrodes were placed on the right and left arms. These electrodes were connected to an amplifier (FE135 Dual Bio Amp; ADInstruments Japan, Inc.) and a recording unit. The ECG waveforms recorded through a noise filter (5–18 Hz) were converted to heart rates via commercial software (LabChart v8; ADInstruments Japan, Inc.).

Swelling/deswelling cycle test

The sample was dehydrated in pure water at 40 °C for 10 min and then swelled in pure water at 25 °C for 10 min. This procedure was repeated twice. The swelling ratio was calculated via the following equation:

where D0 and D denote the diameters of the initial sample and swollen sample, respectively.

Responses