Tailoring the grain boundary structure and chemistry of the dendrite-free garnet solid electrolyte Li6.1Ga0.3La3Zr2O12

Introduction

We have entered an era of energy revolution. Currently, commercial lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are facing technological limitations owing to their high energy and power density requirements1,2,3. All-solid-state lithium-ion batteries (ASSLBs) can be considered excellent resources for manufacturing high-performance energy storage devices, particularly in terms of safety. Among the various solid-state electrolytes (SSEs) that exist, oxide-type electrolytes are considered promising materials due to their high ionic conductivities and extremely low electronic conductivities4,5,6. Many oxide ceramics, such as perovskite-type titanates, NASICON-type phosphates, and garnet-type oxides, have been studied as potential SSEs. In particular, garnet-type Li6.1Ga0.3La3Zr3O12 (LGLZO) has attracted significant attention due to its high ionic conductivity at 25 °C, wide electrochemical window, stable chemical properties, and high resistance of dendrites to Li metal7,8,9,10. Moreover, Newman and Monroe predicted that the high mechanical properties (Young’s modulus: ~150 GPa; shear modulus: ~60 GPa) of LGLZO ceramics can efficiently suppress dendrite formation11. However, several experiments have demonstrated the propagation of dendritic Li along grain boundaries and pores12,13,14,15.

Based on the above research related to dendrite formation, numerous methods, such as spark plasma sintering, two-step sintering, sintering aid addition, and hot pressing, have been investigated to control microstructure16,17,18,19. LGLZO ceramics experience unavoidable Li evaporation under harsh sintering conditions (~1200 °C). Moreover, highly crystallized LGLZO ceramics have high grain boundary resistance values, accelerating dendrite formation and diminishing ionic conductivity. Hence, we have introduced Li2O-B2O3-Al2O3 (LBA) sintering aids to regulate the chemical and structural characteristics of grain boundaries. LBA oxide ceramics exhibit superior ionic conductivities with low melting temperatures of 600 °C20. Importantly, the LBA sintering aid has a an important and beneficial effect on the microstructure by boosting the grain growth of the LGLZO particles in the liquid phase. Furthermore, the LGLZO pellet with the LBA sintering aid exhibits a significantly reduced grain boundary resistance since the LBA ceramic melts and covers the LGLZO grain during the sintering process. We prove that the LBA sintering aid reinforces the resistance of dendrites to Li metal21. Herein, we aim to determine the relationship between the electrochemical performance and microstructure and the influence of this relationship on dendrite formation. Eventually, we determine that the specific mechanism of dendrite formation is associated with electron mobility via the reduction of Li ions. Therefore, the well-designed microstructure of the LGLZO pellet with the LBA sintering aid displays long-term cycling stability without the penetration of Li dendrites.

Recently, the cosintering strategy has garnered significant attention for the commercial utilization of oxide-based ceramic electrolytes. Numerous studies on ASSLBs with LGLZO electrolytes have utilized lithium borate glass electrolytes (e.g., LBA) due to their low sintering temperatures22,23,24. The primary function of LBA glass in a cosintered full battery is to reduce the sintering temperature while filling the pores within the cathode and solid electrolyte membrane. This characterization of LBA glass effectively solves the limitations of oxide-based ASSLBs. Therefore, to realize the practical utilization of ASSLBs with LGLZO electrolytes, we primarily focus on optimizing the solid electrolyte membrane. In this study, comprehensive discussions are conducted to enhance the electrochemical performance characteristics of solid electrolytes, establishing the groundwork for the practical implementation of oxide-based ASSLBs.

Fabrication of the solid-state electrolyte

Li6.1Ga0.3La3Zr2O12 (LGLZO) powder was synthesized by a conventional solid-state method with Li2CO3, Ga2O3, ZrO2, and La2O3 as the starting materials. A total of 10 wt.% excess Li2CO3 was added to compensate for the Li loss during the heating process. Before synthesis, the La2O3 powders were heat treated at 1000 °C for 10 h. These starting materials were ball-milled for 10 h in isopropanol. Then, the mixture was dried at 120 °C for 10 h and heated at 900 °C for 10 h in an alumina crucible at a heating rate of 5 °C/min. To fabricate a pure cubic-phase LGLZO, the mixture was heat treated again. The mixture was ball milled and ground to obtain a fine powder. Li2O-B2O3-Al2O3 (LBA) was fabricated using a conventional melting–quenching process. Stoichiometric ratios of Li2O (97%, Sigma Aldrich), Al2O3 (99%, Sigma Aldrich), and B2O3 (99.98%, Sigma Aldrich) were ball-milled at 250 rpm for 10 h. Then, the mixture was melted at 1050 °C for 1 h. Afterward, the melted mixture was quenched to form small flakes. The flakes were ground and ball milled to obtain a fine powder.

To fabricate the LGLZO pellet with the LBA sintering aid, the prepared LGLZO powder was ball-milled with LBA, and the mixture was pelletized at 70 MPa. The thickness and diameter of the green pellet were 2 mm and 14 mm, respectively. The green pellet was covered with the mother powder to prevent Li evaporation during the sintering process. Then, the green pellet was sintered at 1200 °C for 10 h in an alumina crucible. Afterward, the sintered pellet was polished with 300- to 2000-grit sandpaper before cell assembly.

Structural and electrochemical characterization

The crystal structures of the LGLZO samples were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (Bruker AXS GmbH, D8 Discover plus) in the 2θ range of 10°–60° at a scan rate of 0.1°/sec. Rietveld refinement was utilized to determine the crystal structure of LGLZO using the High Score Plus program (PANalytical). The surface and cross-sectional images of the sintered LGLZO pellets were obtained using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; JEOL, JSM-7900F). The relative densities of the LGLZO pellets were obtained by the Archimedes method using alcohol (Mettler–Toledo density measurement attachments). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was conducted at 25 °C using an AC impedance analyzer (SP-300, EC-lab) at frequencies ranging from 1 Hz to 7 MHz and an amplitude of 20 mV. Before performing the EIS measurements, both surfaces of the pellets were sputtered with gold serving as a blocking electrode (COXEM, SPT20). The electronic conductivity was measured using a DC polarization method by applying 10 mV with an Au symmetric cell configuration. The distribution of relaxation time (DRT) was determined using MATLAB R2023a software. Galvanostatic cycling was conducted using a Li/Li symmetric cell configuration. Li metal was placed on both surfaces of the LGLZO samples, and the Li/LGLZO/Li symmetric cell was heated at 200 °C for 1 h. A Swagelok cell was used to measure the cycling performance characteristics of full batteries with LGLZO electrolytes. The composite cathode was prepared by mixing 80 wt.% LiFePO4 (LFP) cathode and LGLZO powder (50:50 ratio), 10 wt.% conducting agent (super-p), and 10 wt.% poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) in N-methyl pyrrolidinone (NMP). The composite cathode slurry was coated on the surface of the LGLZO pellet and dried at 120 °C for 12 h in a vacuum oven. For the counter electrode, Li metal was attached to the opposite surface and heated at 200 °C until the Li metal melted. The assembled full batteries were evaluated at voltages ranging from 2.5 V to 4.1 V at 60 °C.

Microstructural and mechanical properties of LGLZO

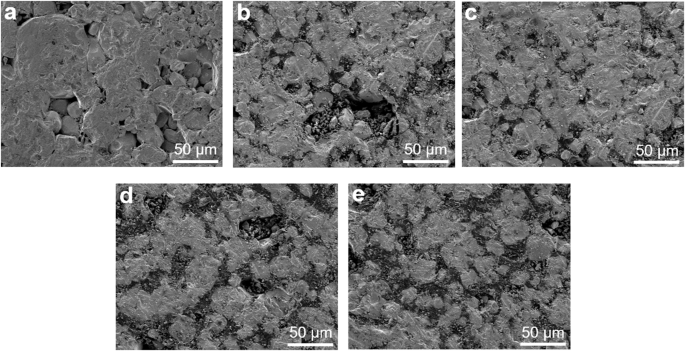

Figure 1 shows the surface microstructures of the as-prepared LGLZO pellets with different contents of the LBA sintering aid (0%, 3%, 5%, 7% and 10%). In Fig. 1a, the sintered LGLZO pellet without a sintering aid (denoted as LGLZO_0) displays a low relative density and a porous structure due to the intergranular contact properties being insufficient. Surprisingly, these pores and loose grain boundaries almost disappear with the addition of LBA, as shown in Fig. 1b–e25. The LGLZO pellets with sintering aid contents of 3%, 5%, 7%, and 10% (denoted as LGLZO_3, LGLZO_5, LGLZO_7, and LGLZO_10, respectively) display excellent densification, and their voids are filled with melted LBA. Therefore, we can predict that the LGLZO pellets with sintering aids have better ionic conductivities than LGLZO_0 due to the well-designed grain-to-grain bonding26. Moreover, the LBA present at the grain boundaries contributes to the reduction in the electronic conductivity. It is well known that electrons are preferentially transported along grain boundaries; thus, the mobility of electrons is significantly decreased due to the presence of tight grain boundaries and dense structures27,28. Generally, the grain growth of ceramic particles occurs during high-temperature sintering. Therefore, LGLZO_0 shows imperfect densification. The LBA sintering aid enhances the liquid phase sintering process due to its low melting point (600 °C) and its ability to fill void spaces. The relative density is summarized in Table 1. LGLZO_0 has an inferior relative density of 88.52%, while LGLZO_3, LGLZO_5, LGLZO_7, and LGLZO_10 have superior relative densities of 91.82%, 93.47%, 95.51% and 96.18%, respectively. Furthermore, we have assessed the mechanical performance characteristics of the LGLZO pellets. The hardness results coincide with the relative density results, as mentioned above. The effects of the grain size and porosity on the hardness can be described by the Hall‒Petch equation. In addition, the effect of grain size is negligible when the particle size is larger than 0.25 μm. Hence, the effect of grain size can be neglected because it substantially exceeds 0.25 μm. Therefore, Eq. (1) indicates the relationship between the porosity and hardness:

where the hardness is H, the ideal hardness of materials is H0, the exponential constant is n, and the porosity is p. The relationships between the mechanical properties and densification can be ascertained by utilizing Eq. (1). Therefore, the sintering aid improves the mechanical properties by filling the void spaces of the LGLZO pellets.

a LGLZO_0, b LGLZO_3, c LGLZO_5, d LGLZO_7, and e LGLZO_10.

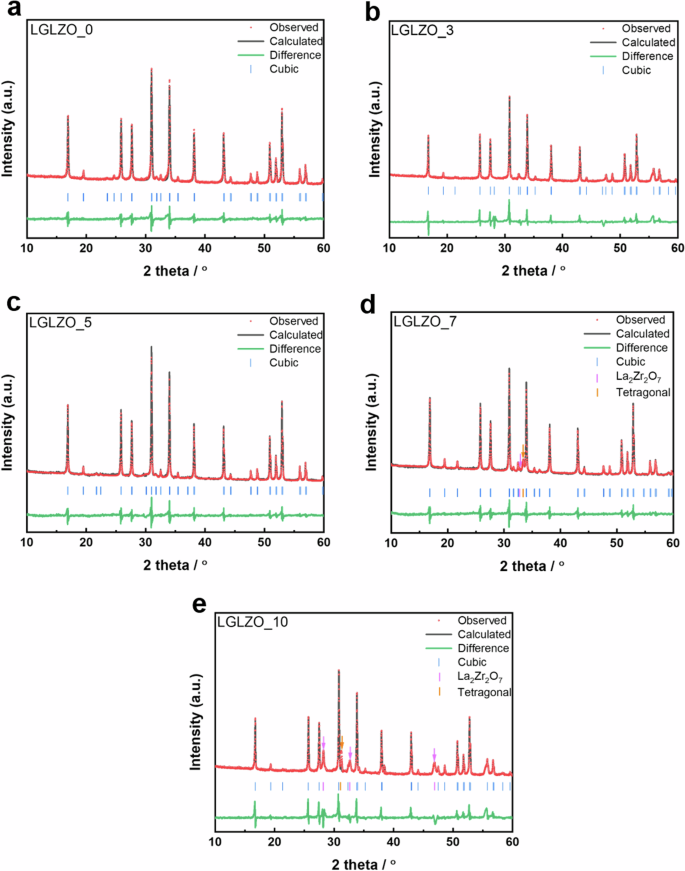

As shown in Fig. 2, XRD analysis has been conducted to identify the crystal structures of the as-prepared LGLZO pellets. All the samples show highly crystallized structures, which correspond to the previously reported cubic phase LGLZO. In Fig. 2a–c, LGLZO_0, LGLZO_3, and LGLZO_5 display clear XRD patterns without impurities. Conversely, when the sintering aid content exceeds 7%, distinct impurities of La2Zr2O7 (marked with a purple arrow) and a tetragonal phase (marked with an orange arrow) emerge. Our observation indicates that an unwanted side reaction occurs due to the excess LBA sintering aid. Typically, La2Zr2O7 pyrochlore forms when Li is depleted or lacking in the LGLZO lattice structure. Therefore, we propose that excessive amounts of sintering aid can lead to significant Li evaporation. Notably, the tetragonal phase is observed alongside the La2Zr2O7 phase in both LGLZO_7 and LGLZO_10. This observation strongly correlates with the occurrence of Li evaporation caused by excessive sintering aid. Since LGLZO is present in the cubic phase, the critical Li vacancy concentration is between 0.4 and 0.5 vacancies per formula unit. Consequently, an overly high LBA content leads to a high Li vacancy concentration due to severe Li evaporation, resulting in a phase transition from the cubic phase to the tetragonal phase. Therefore, we determine that the optimal sintering aid content is 5%. This content can mitigate the appearance of any impurities and maintain a clear cubic phase of LGLZO. To compare the degree of crystallinity, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) is investigated for all the samples, and the results are summarized in Table 1. A narrow FWHM signifies the presence of a highly crystallized structure, thereby reinforcing the electrochemical performance. The obtained FWHM values of the LGLZO_x samples are 1.34, 1.18, 1.16, 1.19, and 1.21 when x = 0, 3, 5, 7, and 10, respectively (Table 1).

a LGLZO_0, b LGLZO_3, c LGLZO_5, d LGLZO_7, and e LGLZO_10.

Influences of grain boundaries on ionic conductivity

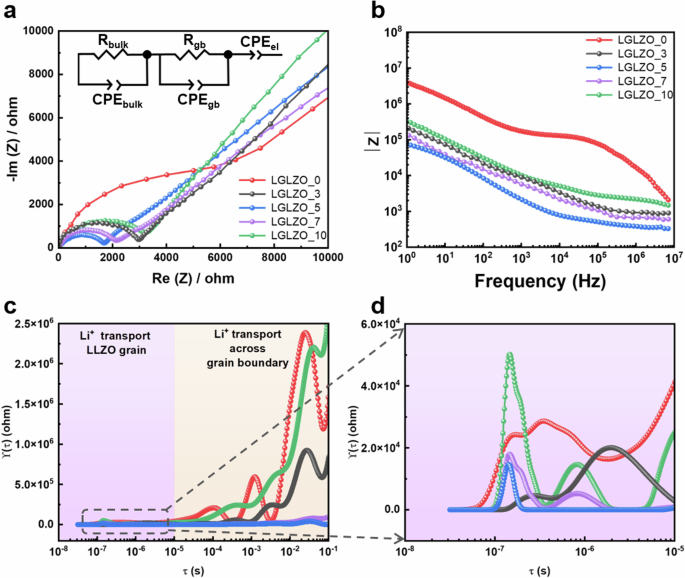

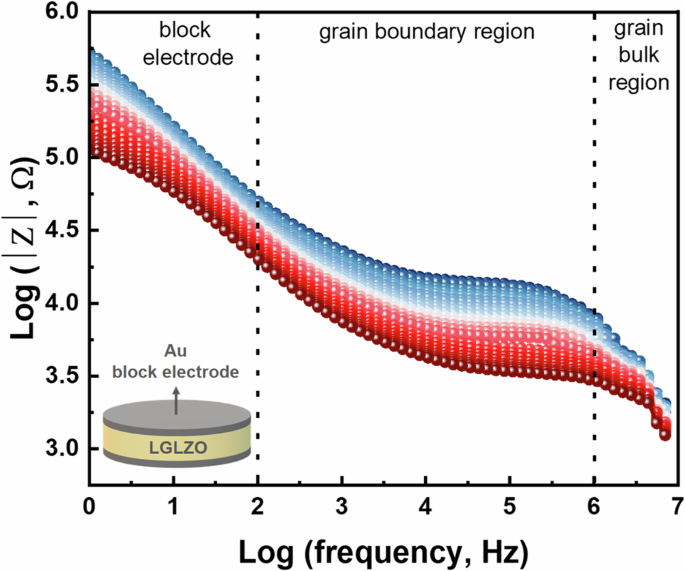

Figure 3 shows the results of AC impedance analysis for five LGLZO samples. The Nyquist plots of the Au/Au symmetric cells show one semicircle and a long tail due to the Au blocking electrode, as shown in Fig. 3a. An equivalent circuit model of (RbCPEb)(RgbCPEgb)(CPEel) is utilized to fit the impedance spectra29. R indicates the resistance, CPE indicates the constant phase, and the subscripts b, gb, and el indicate the grain bulk, grain boundary, and Au blocking electrode, respectively. The resistance component in the LGLZO pellet consists of bulk and grain boundaries, which are represented by one semicircle in the high-frequency region. Therefore, the specific impedance of the bulk and grain boundary resistance is difficult to determine. The ionic conductivity of the LGLZO pellets is calculated with Eq. (2):

where σ is the ionic conductivity, R is the total resistance of the LGLZO pellet (bulk and grain boundary contributions), and L and S are the thickness and electrode surface area of the LGLZO pellet, respectively30. The calculated ionic conductivities of the LGLZO_x samples are 2.41 × 10−4, 5.67 × 10−4, 8.86 × 10−4, 7.25 × 10−4, and 4.53 × 10−4 S cm−1 at 25 °C when x = 0, 3, 5, 7 and 10, respectively. As mentioned above, the ionic conductivities of oxide ceramic electrolytes strongly depend on the grain boundary resistance. Therefore, the relatively low ionic conductivities of the LGLZO_0 samples are caused by the remaining void spaces and loose grain boundaries. Conversely, the LGLZO samples with sintering aids display superior ionic conductivities to that of LGLZO_0 due to the absence of pores and well-designed chemistries and structures of grain boundaries. The ionic conductivities of LGLZO_7 and LGLZO_10 are lower than that of LGLZO_5, even though their relative densities are higher. It is well known that relative density has an advantage in improving ionic conductivity, but there are other important factors in addition to relative density. As discussed above in the XRD analysis (Fig. 3), LGLZO_7 and LGLZO_10 include the La2Zr2O7 pyrochlore and tetragonal phases due to Li volatilization. Thus, LGLZO_7 and LGLZO_10 show less ionic conductivity than LGLZO_5. Figure 3b shows the Bode plots corresponding to the Nyquist plots. Considering the overall frequency, the LGLZO_5 sample shows the lowest impedance, and the LGLZO_0 sample shows the highest impedance. These results agree with the Nyquist plots. Importantly, a noticeable increase in the impedance of LGLZO_0 is observed in the frequency range from 104 to 105 Hz, which is related to the grain boundary resistance. In Fig. 3c, d, the distribution of relaxation time (DRT) method is utilized to elucidate and specify the differences in grain boundary contributions due to the influence of the sintering aid. DRT is a powerful approach in the research of SSEs, where the grain bulk and intergranular resistance values are expressed as one semicircle. The time constant distribution can be used to separate various physical processes such as bulk, grain boundary, and interface resistance. The ZDRT is expressed by transforming the as-prepared impedance result with a time constant distribution and frequency, as shown in Eq. 3:

where Z* is the complex impedance, ({R}_{infty }) and ({R}_{p}) are the series resistance and the overall polarization, respectively, and τ, ω, and G are the time constant, angular frequency, and DRT, respectively31. Then, Eqs. (4) and (5) are utilized to separate the real part of the impedance (Z´) and the imaginary part of the impedance (Z´´), respectively. Finally, Eq. (6) expresses the simple DRT formula.

a Nyquist plots, b Bode plots, c corresponding DRT results, and d enlarged DRT results of LGLZO_0, LGLZO_3, LGLZO_5, LGLZO_7, and LGLZO_10.

Figure 3c displays the DRT results in the middle- and high-frequency regions. Two types of resistance components are presented: i) Li+ ion transport through the LGLZO grain bulk and ii) Li+ ion transport across the LGLZO grain boundary32. At high frequencies, the five DRT spectra exhibit negligible differences. In contrast, there are significant differences in the middle-frequency region associated with grain boundary resistance. The LGLZO_0 sample shows the largest polarization peak due to its porosity and poor grain boundary structure. Importantly, the LGLZO_5 sample shows extremely low polarization peaks in the middle-frequency region, hence proving the effect of a well-designed microstructure in reducing the grain boundary resistance. Additionally, LGLZO_10 exhibits polarization peaks similar to those of LGLZO_0 in the overall frequency region owing to the evaporation of Li and the presence of an impurity phase. Figure 3d shows the magnified high-frequency region, which is related to Li+ transport through the LGLZO grains. The LGLZO_0 and LGLZO_10 samples exhibit notably high polarization peaks in the grain bulk area. We propose that the high resistance observed in LGLZO_0 is caused by insufficient grain growth during the sintering process. However, LGLZO pellets with sintering aids exhibit relatively low resistance due to sufficient grain growth. In addition, LGLZO_10 shows high resistance in the grain bulk area. This phenomenon is caused by the impurity phase, and it coincides with the XRD analysis results.

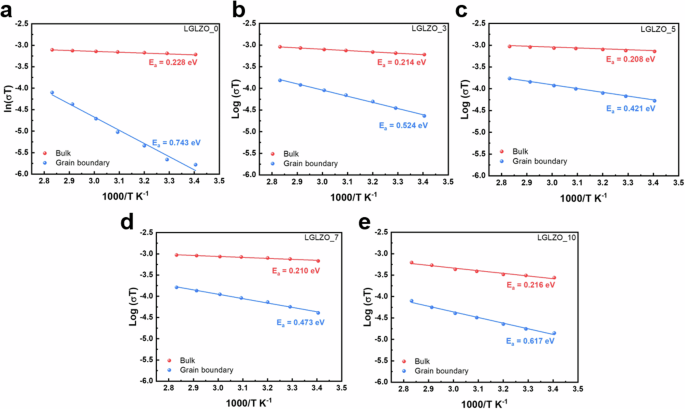

To determine the temperature dependence levels of the LGLZO pellets, ionic conductivity measurements are conducted from 293.15 K to 353.15 K. The activation energy (Ea) values of the bulk and grain boundary contributions are measured by the Arrhenius law:

where σ indicates the ionic conductivity, A indicates the preexponential factor, T indicates the absolute temperature, and K indicates Boltzmann’s constant. Although the Nyquist plot is useful for impedance analysis, it has several limitations: i) the absence of exact information about the number of poles and the frequency and ii) if the response frequency domain of the polarization peaks does not differ by a factor of 100, the physical processes overlap, thus impeding the analysis of a specific impedance. Therefore, many researchers have only provided the total Ea of the solid electrolyte, and they have not calculated the specific Ea values of the bulk and grain boundaries33,34,35,36. Figure 4 displays the Ea values of the bulks and grain boundaries for five LGLZO samples. The LGLZO_0 sample presents bulk and grain boundary Ea values of 0.228 eV and 0.743 eV, respectively (Fig. 4a). This result reveals a significant difference between the bulk and grain boundaries, proving the poor Li+ transport pathway at the grain boundaries. In contrast, LGLZO_5 exhibits significantly reduced bulk and grain boundary Ea values of 0.208 eV and 0.421 eV, respectively, which indicates enhanced Li+ transport in the grain boundary region (Fig. 4c). The Ea values of the five samples are summarized in Table 1.

Arrhenius plot for bulk and grain boundary ionic conductivity of a LGLZO_0, b LGLZO_3, c LGLZO_5, d LGLZO_7, and e LGLZO_10.

To clarify the bulk and grain boundary contributions of Li+ transport within the solid-state electrolytes, we present a Bode plot of the LGLZO_5 sample at various temperatures (Fig. 5). According to the Arrhenius equation, a wide disparity in resistance with temperature corresponds to a relatively high Ea, which impedes ion conduction. In Fig. 5, the Bode plots are divided into three frequency regions: i) low-frequency regions related to the interfacial resistance between the block electrode and solid-state electrolyte (this resistance component is not discussed in this system), ii) middle-frequency regions related to the grain boundary contribution, and iii) high-frequency regions related to the grain bulk region. The difference in resistance is notably lower in the high-frequency region than in the middle-frequency region, which indicates that the Ea value is low in the grain bulk region.

Bode plot of LGLZO_5 ranging from 293 to 333 K.

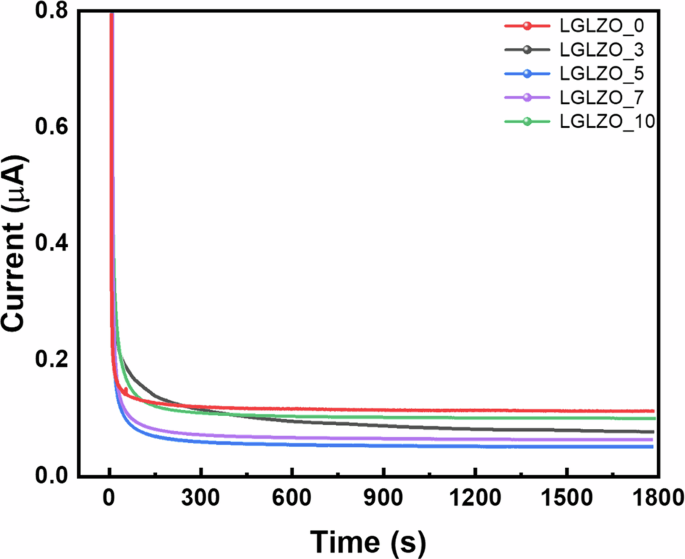

The electronic conductivities of solid-state electrolytes are crucial for determining the cycling performance of a battery. Since a solid electrolyte has a high electronic conductivity, unwanted side effects, such as leakage current, and a soft-short circuit occur in ASSLBs. To the best of our knowledge, electrons are primarily transported along grain boundaries and pores. Therefore, designing a grain boundary structure and chemistry is an effective method for enhancing cycling performance. The electronic conductivity (({sigma }_{e})) is calculated by the following equation:

where I is the steady-state current, d is the thickness of the sample, U is the applied voltage and A is the area of the sample. The DC polarization profiles are presented in Fig. 6. The LGLZO_5 sample shows the lowest electronic conductivity with a low steady-state current. This finding is in good agreement with well-designed grain boundaries inhibiting electron movement, thereby reducing the electronic conductivity. The electronic conductivities of all the samples are summarized in Table 1.

DC polarization curves of LGLZO_0, LGLZO_3, LGLZO_5, LGLZO_7, and LGLZO_10.

In-depth analysis of the degradation mechanism

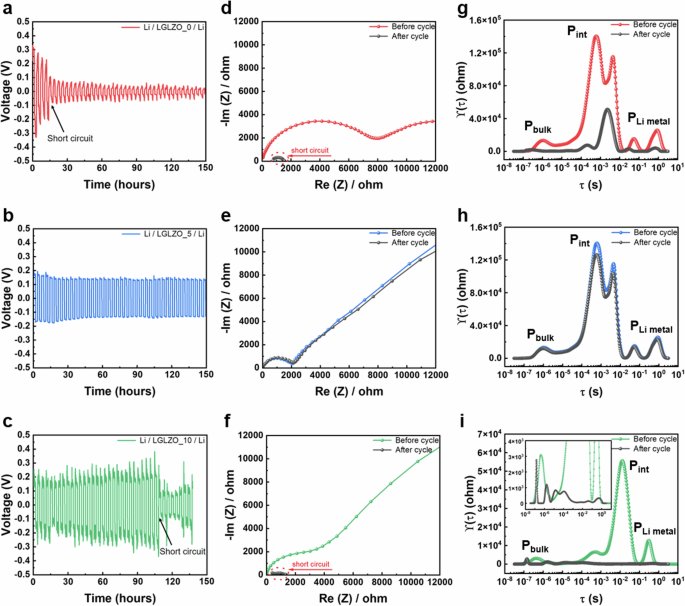

Figure 7a–c shows the galvanostatic cycling results of LGLZO samples with Li/Li symmetric cell configurations at a current density of 0.2 mA cm−2. The LGLZO_0 sample exhibits poor cycling performance, with severe polarization and a short circuit occurring in only 15 h. In contrast, the LGLZO_10 sample exhibits enhanced cycling performance, with a short circuit occurring in 117 h. When a short circuit appears, the Li symmetric cell suffers a sudden voltage drop due to the propagation of Li dendrites. In contrast, the LGLZO_5 sample shows stable long-term cycling for more than 150 h without short circuiting. Therefore, we confirm that the Li dendrites are successfully suppressed by designing the chemical and structural characteristics of the grain boundaries, as dendritic Li propagates along the grain boundaries. The formation of Li dendrites is proven through impedance analysis, as shown in Fig. 7d–f. The impedances of LGLZO_0 and LGLZO_10 for the LGLZO bulk and grain boundaries prior to cycling are 7989 and 3894 Ω, respectively. Notably, the impedances (Rb + Rgb) for LGLZO_0 and LGLZO_10 display significantly diminished semicircles due to short-circuit failure after cycling (indicated by a red circle). In contrast, the LGLZO_5 sample demonstrates negligible differences before and after cycling, showing superior resistance against Li dendrites. Figure 7g–i shows the corresponding DRT results before and after cycling. In the DRT spectra, three types of polarization peaks are observed: i) the sum of the LGLZO bulk and grain boundary resistance components in the high-frequency domain (PLGLZO), ii) the interfacial resistance component between Li metal in the middle-frequency domain (Pint), and iii) the resistance component for Li+ diffusion in the Li metal electrode in the low-frequency domain (PLi metal). Both LGLZO_0 and LGLZO_10 show distinct polarization peaks before cycling and significantly reduced peaks after cycling due to Li dendrite formation (Fig. 7g, i). Furthermore, the DRT results show a shift and a considerable decrease in polarization peaks in Pint and in PLZZO, demonstrating that Li dendrites penetrate the inside of the LGLZO pellets from the interface. Conversely, LGLZO_5 shows no significant difference before and after cycling due to the presence of well-designed grain boundaries (Fig. 7h).

Galvanostatic cycling profiles of Li/Li symmetric cells at 0.2 mA cm−2 for a LGLZO_0, b LGLZO_5, and c LGLZO_10. Nyquist plots of Li/Li symmetric cells cell before and after cycling of d LGLZO_0, e LGLZO_5, and f LGLZO_10. DRT analysis plot corresponding to the impedance spectra of g LGLZO_0, h LGLZO_5, and i LGLZO_10.

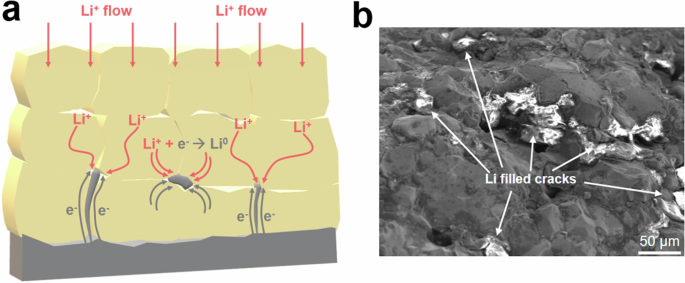

Figure 8a shows a schematic of Li dendrite formation in the LGLZO pellet. In general, electrons are preferentially transported along grain boundaries and pores, and the electronic conductivity of LGLZO causes leakage current and Li dendrite formation. Since electronically charged grain boundaries and pores generate Li dendrites via the reduction of Li ions, LGLZO pellets with poor microstructures suffer cell failure and short circuits37,38. Additionally, the Li dendrites react with oxygen atoms in the LGLZO lattice to form byproducts (e.g., Li2O), thereby deteriorating the LGLZO39. Figure 8b shows the propagation of Li dendrites along the grain boundaries and cracks. Numerous dendritic Li grains are observed in the cross-section of the LGLZO_0 sample. Consequently, we clarify the influence of the microstructure on Li dendrite growth.

a Schematic of Li dendrite formation in LGLZO pellet. b After cycle cross-section FE-SEM image of LGLZO_0.

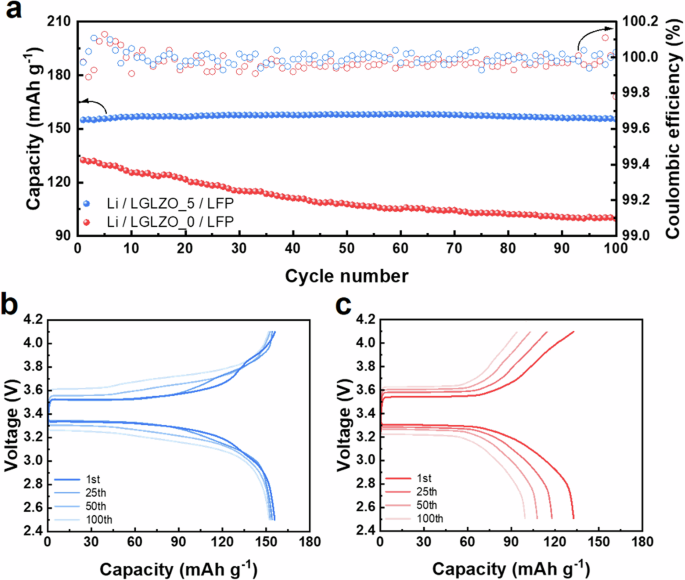

To compare the cycling performance characteristics of LGLZO_0 and LGLZO_5, a full battery with a cell configuration comprising an LFP + LGLZO composite cathode, an LGLZO solid electrolyte, and a Li metal anode is assembled (denoted as Li/LGLZO_0/LFP and Li/LGLZO_5/LFP, respectively). Figure 9a shows the cycling performance properties of the prepared full batteries in the voltage range of 2.5–4.1 V at a cycling rate of 0.2 C at 60 °C. Li/LGLZO_5/LFP and Li/LGLZO_0/LFP exhibit initial discharge capacities of 155.8 mAh g−1 and 132.8 mAh g−1, respectively. The charge‒discharge profiles exhibit significant increases in their potential gaps during cycling, indicating severe polarization due to the presence of interfacial resistance between the cathode and solid electrolyte caused by the volume expansion of LFP cathode materials (Fig. 9b, c). Nevertheless, Li/LGLZO_5/LFP retains 98.5% and 96.7% of the capacity after the 50th and 100th cycles, respectively. Conversely, Li/LGLZO_0/LFP shows rapid capacity fading. Additionally, the capacity retention at 50 cycles is 81.8%, and it decreases to 75.7% at 100 cycles, indicating poor cycling performance. The poor cycling performance of LLZO_0 is attributed to its relatively high resistance and electronic conductivity due to its porous structure, thus inducing dendrite formation and leading to irreversible lithium loss.

a Cycling performance and coulombic efficiency of the Li/LGLZO_0/LFP, and Li/LGLZO_5/LFP cell, charge–discharge profile of the b Li/LGLZO_5/LFP, and c Li/LGLZO_0/LFP.

Conclusion

In this study, we aim to optimize the microstructure of LGLZO by introducing a sintering aid. To the best of our knowledge, the ionic conductivities of oxide solid-state electrolytes heavily rely on the presence of pores and grain boundaries. Therefore, designing the microstructure is crucial for improving the electrochemical performance characteristics of solid-state electrolytes. Our findings indicate that the LGLZO_5 pellet exhibits an enhanced ionic conductivity of 8.86 × 10−4 S cm−1 because of the optimized ratio of the sintering aid. Furthermore, the XRD patterns suggest that the LGLZO_5 pellet has a well-crystallized cubic structure of LGLZO with a narrow FWHM. Additionally, the excess amount of sintering aid leads to side reactions due to the evaporation of Li within the LGLZO lattice. The activation energies of the LGLZO_5 pellet are 0.208 eV and 0.421 eV, corresponding to the bulk and grain boundary contributions, respectively. Notably, the reduced activation energy of the grain boundary demonstrates enhanced Li-ion transport in the grain boundary region. Importantly, since dendritic Li propagates along the grain boundaries, the well-designed chemical and structural characteristics of the grain boundaries of the LGLZO_5 pellet effectively prevent the formation of Li dendrites. In this paper, we suggest enhanced methods for reinforcing the ionic conductivity and for stabilizing the resistance to Li metals.

Responses