Thermoregulatory integration in hand prostheses and humanoid robots through blood vessel simulation

Introduction

With the development of artificial intelligence (AI) technology, service robots are becoming increasingly popular. Humanoid robots are already performing anthropomorphic AI services that provide convenience to customers, such as the delivery of goods, nursing, and educational services. Even as humanoids become increasingly common in daily activities, some people may find the alien feel of robots and their inherently hard and cold contact uncanny1,2, especially when robots take on roles in more personal contexts, such as in the health care or service industries. Similarly, discomfort might arise when wearing a prosthetic hand or leg or encountering someone with one. While many past studies have delved into skin material (soft vs. hard) and interaction dynamics (robot-focused vs. human-focused)3,4, tactile sensations have often been overlooked. Recent efforts have successfully replicated the texture and firmness of real skin by simulating its exterior, fatty, and muscle layers5,6. However, the feeling of temperature remains an essential aspect of the tactile experience. The warmth or cold perceived through touch can profoundly influence human–robot interactions, affecting emotions such as trust, companionship, and overall comfort7,8,9,10. Therefore, to develop artificial skin technology similar to natural human skin for infrared camera recognition and touch, a soft and elastic surface texture and a temperature distribution similar to the actual body temperature needs to be imitated. In many e-skin studies, silicone rubber and foam materials reproduce the smooth and elastic surface texture of skin11,12,13. According to existing research, the Peltier device, resistive heater, and thermoelectric modules are used to control the temperature14,15,16. However, when applied to the broad surface of humanoids or prosthetic hands/legs, wiring becomes a problem, and a diverse temperature distribution similar to that of the human body is difficult to form. If this technology can be applied to imitate the human body’s skin temperature regulation function, it can be practical and helpful in forming a temperature distribution similar to the actual body temperature.

To reproduce the natural skin temperature similar to that of the human body, the body’s temperature regulatory mechanism needs to be understood through the circulatory system, and a thermal control system that mimics it needs to be developed. The human circulatory system enables a vast array of complex and interrelated functions centered on the circulatory pathways of the bloodstream. Thermoregulation is a primary function of this system and is crucial for homeothermic organisms such as humans. Thermoregulation allows the maintenance of a constant core body temperature, ~37 °C, irrespective of external environmental changes. This intricate process involves various physiological responses: modulation of heart rate, vasodilation and vasoconstriction of blood vessels, sweating, non-shivering thermogenesis, and thermogenic activities in brown adipose tissues17,18. Central to thermoregulation is the heart’s role in ensuring homeostasis. The heart adjusts its rate based on external temperature variations, thereby controlling blood flow and, consequently, body temperature19,20,21. Blood vessels are essential in this process, directing the heat generated by metabolic activities. The blood vessels use blood as a heat distribution medium and manage heat dissipation by dilating or constricting in response to external temperature changes22,23.

In this study, a groundbreaking artificial skin that replicates the thermoregulatory functions inherent to human skin was developed. Our study drew its inspiration from the role of the human vascular system in thermoregulation. Thermoregulatory artificial skin was fabricated by covering a silicone-based artificial skin layer on blood vessel-mimicked fiber made of stretchable and elastic silicone. Within this design, water, acting as a heat medium, circulated through the vessel-mimicked fibers. This circulation was similar to the heart pumping blood throughout the body and was regulated at various temperatures, flow rates, and frequencies. We conducted a comprehensive analysis of the volume change patterns of these artificial fibers based on water parameters, linking them with heat dissipation properties. In addition, we studied the thermal infrared temperature and distribution patterns of this artificial skin concerning variations in skin thickness and fiber configurations. Based on the experimental results, thermoregulation artificial skin was applied to the mannequin face and robot hand to determine the temperature and distribution of the thermal infrared rays generated from a person’s face and hands. This innovation provides solutions to the challenges faced by individuals using prosthetic hands, potentially reducing discomfort during skin-to-skin interactions. In the future, this technology could find extensive use in robotic limbs and faces, enhancing the natural feel and comfort of human–robot interactions.

Materials and methods

The thermoregulation artificial skin production process was divided into the following steps. (i) Fabrication of the blood vessel-mimicked fiber and control of the heat dissipation characteristics; (ii) fabrication of the artificial skin in the shape of a plane, face, and hand; (iii) thermoregulation of the artificial skin applied to the mannequin’s face and robot’s hand; and (iv) measurement of the properties of the blood vessel-mimicked fibers and thermoregulation artificial skin.

We employed stretchable and elastic silicone to create fibers similar to blood vessels, and each had a hollow diameter of ~500 μm. These fibers were embedded within a silicone-based artificial skin layer, allowing flexible movements, including wrinkling, stretching, and bending, culminating in a thermoregulatory skin system. The results from the experiments on parameters of water temperature, flow rate, frequency, skin thickness, and fiber arrangement facilitated the mimicking of the thermal infrared temperature and distribution patterns observed in human faces and hands.

Fabrication of the blood vessel-mimicked fiber and control of heat dissipation characteristics

We produced a fiber resembling a blood vessel using a meticulous process. Liquid silicone (Ecoflex 00-35, Smooth-On, Inc.) was applied and cured onto a carbon rod with a 0.5 mm diameter obtained from RC Lab. The silicone compound was a blend of Part A (a prepolymer) and Part B (a curing agent) mixed in a 1:1 mass ratio. Silver foil, which was laid flat on a work surface, acted as the base for the silicone application. The carbon rod, which was attached to an electric drill (Model L514, ES), was set upon this layer. The drill was operated at ~35 rpm to ensure that the rod received a uniform silicone coating. Before the 5-min curing process, the rod was continuously rotated to prevent silicone displacement due to gravity. This process was repeated four times to achieve the desired rod thickness. After the fifth coat, the silicone-coated rod had an external diameter of ~2 mm. The silicone was then separated from the carbon rod, and this process resulted in a fiber resembling a blood vessel with an internal hollow diameter of ~500 μm.

The circulation system’s water inflow was set to maintain temperatures between 30 and 70 °C; here, we used a 2 L beaker filled with 1.8 L of water and placed it on a heating plate (model MSH-20D, DAIHAN Scientific). An external temperature probe (model DH. WMH03021, DAIHAN Scientific) connected to the plate ensured accurate temperature control. A peristaltic pump (model BT300-2J, Longer) accompanied by a 1250 mm long and 2.4-mm-diameter tube (#19, Longer) facilitated water flow into the fiber. A circulation system was established: water heated in the beaker was pushed into the fiber by the pump and then returned to the beaker. The 19# tube was connected to the beaker and three 400 mm fiber lengths via a three-way connector (model QN659250, NEEDLE STORE). The end of the fiber was linked back to the beaker using an 800 mm 19# tube. A micro silicone tube (2 mm diameter) served as a bridge for these connections. The water flow rate in the fiber, ranging from 1.10 to 11.0 cc/m, was regulated by adjusting the pump’s speed between 10 and 120 rpm. An Arduino system integrated with the pump enabled the precise control of the water inflow frequency, which was adjustable between 1 and 8 Hz. The system underwent experimental testing to assess its reliability, specifically checking for potential leaks at tube junctions under different water flow conditions.

Fabrication of the artificial skin in the shape of a plane, face, and hand

The procedures for fabricating artificial skin in planar, facial, and hand forms are outlined as follows: Planar artificial skin fabrication: The silicone rubber used (Mold Max 14 NV, Smooth-On, Inc.) was a combination of Part A (prepolymer) and Part B (curing agent) mixed in a 10:1 mass ratio. For the desired shade of the artificial skin, 0.6 ml of apricot-colored silicone pigment solution (YOUNGNAM) was added to 300 × g of silicone rubber. Once thoroughly mixed, the concoction was poured into a metal tray measuring 599 × 402 × 30 mm3 to create four distinct thicknesses: 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 mm. The thickness of the artificial skin was determined by referring to the average thickness of human skin, which ranges from 1.5 to 4.0 mm, and the average thickness of the eyelid, which is ~0.5–0.6 mm24,25. This mixture was then left to cure under ambient conditions for 4 h.

Facial artificial skin fabrication: A facial shape was captured by applying a 1-mm-thick plaster bandage onto a mannequin face, followed by air drying for 12 h. To replicate the face, a mold was crafted using silicone mold rubber (Mold Max 60, Smooth-On, Inc.). This involved mixing Part A (prepolymer) and Part B (curing agent) in a 100:3 mass ratio. The mannequin face impression was immersed in this silicone mixture. After curing for 12 h, the impression was removed, providing a mold for facial design. The artificial skin mixture was poured into this mold and allowed to set for another 4 h, producing a 1-mm- thick piece of facial skin. A release agent (ER-200, Mann) was sprayed within the mold to facilitate the easy removal of the developed skin.

Hand-shaped artificial skin fabrication: Dense liquid silicone rubber was applied over a bare robotic hand, revealing only its skeletal framework, and then cured in open air for 4 h. The previously described fiber, which resembles blood vessels, was laid over this silicone layer. Above this configuration, a 1.0 mm thick planar artificial skin was positioned. To ensure this, the flat skin was cut into six distinct pieces to cover the five fingers and the back of the hand.

Thermoregulation artificial skin applied to the mannequin’s face and robot’s hand

The thermoregulation artificial skin was developed to mirror the thermal infrared features of a human face and hand, and two pumps were utilized for its development: peristaltic pump A and peristaltic pump B (BT100-2J, Longer). The comprehensive fabrication processes for both face and hand designs are detailed as follows:

Face-Shaped Thermoregulation Artificial Skin Fabrication: Six blood vessel-mimicked fibers were linked to both peristaltic pumps A and B using three-way connectors, and each pump was connected to three strands. These fibers were then arranged on a mannequin face, following the thermal distribution patterns observed in an actual human face. Face-shaped artificial skin was then placed over these fibers.

Hand-Shaped Thermoregulation Artificial Skin Fabrication: Nine fibers resembling blood vessels were integrated into the design. Peristaltic pump A was connected to six fibers via one three-way connector and three Y connectors (QN830160, NEEDLE STORE), while pump B was connected directly to three fibers through one three-way connector. In accordance with the thermal distribution of a real hand, these fibers were positioned atop a silicon layer on a robotic hand’s skeletal structure.

Hand-Shaped Thermoregulation Artificial Skin Fabrication: Nine fibers resembling blood vessels were integrated into the design. Peristaltic pump A was connected to six fibers via one three-way connector and three Y connectors (QN830160, NEEDLE STORE), while pump B was connected directly to three fibers through one three-way connector. In accordance with the thermal distribution of a real hand, these fibers were positioned atop a silicon layer on a robotic hand’s skeletal structure. Sections of a plane-shaped artificial skin were layered on top of these fibers.

Measurement of the properties of the blood vessel-mimicked fibers and thermoregulation artificial skin

In the final stage of this study, the engineered fibers, which mimicked blood vessels, were subjected to thorough examination to evaluate their structural and mechanical characteristics. Using field effect scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; JSM-7610F PLUS, JEOL), we performed a thorough examination of the surface and the cross-sectional architecture of these fibers. This provided invaluable information regarding their morphological features. In addition, their mechanical attributes, including the resilience and endurance of the material under various stressors, were determined using a universal testing machine (UTM; TD-U01, T&DORF, Inc.).

To deepen our understanding of the capabilities and effectiveness of the thermoregulation artificial skin, we performed a sequence of tests. These were designed to investigate potential disruptions or interferences concerning thermal infrared temperature and distribution. Our experimental framework employed a hot plate, calibrated to specific temperatures of 30, 50, and 70 °C, alongside ice water kept at its freezing threshold. These elements acted as heating and cooling agents, respectively. These elements were positioned beneath the artificial skin and facilitated observations of the potential shifts or disruptions in the thermal features. In the case of face-shaped thermoregulation artificial skin, to facilitate circulation, peristaltic pump A circulated water at 54 °C, operating at 5.39 cc/min and 2 Hz for 15 min. Concurrently, peristaltic pump B functioned at 4.47 cc/min and 2 Hz, using water at 52 °C for the same duration. In the case of hand-shaped thermoregulation artificial skin, for circulation, over a period of 15 min, pump A operated at 6.26 cc/min and 2 Hz with 52 °C water, whereas pump B worked at 5.39 cc/min and 2 Hz, circulating water at 50.5 °C. The instrument used for this stage was a thermal infrared imaging camera (T420, FLIR systems). This device captured infrared images of both the fiber and the skin. Subsequent analysis of these infrared signals was facilitated through FLIR Tools software. This analysis revealed the temperature oscillations and presented a holistic view of the thermoregulatory proficiency of the artificial skin. This evaluation was integral in confirming the artificial skin’s capacity to accurately reflect the inherent thermal attributes of human skin.

Results

Concepts of the thermoregulation of artificial skin

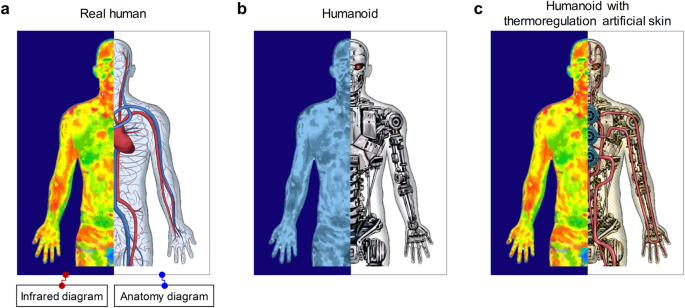

The human body’s thermoregulatory mechanism is crucial for maintaining a relatively consistent body temperature, ~36.5 °C, despite external environmental shifts. As shown in Fig. 1a, a thermal infrared imaging camera illustrates the diverse temperature spread across the various regions of the skin. The core organs of the body contribute ~70% of the total body heat, with the residual heat being sourced from the skin and peripheral tissues. Given the modest heat generation of skin tissues, temperature disparities manifest across different skin regions. These disparities are primarily dictated by the warmth of arterial pathways, which are influenced by central organs and juxtaposed with the cooling veins at the surface.

Diagrams illustrating the thermal infrared distribution in a actual humans, b humanoids, and c humanoids equipped with thermoregulation artificial skin.

In addition, the blood vessels located beneath the skin surface play a pivotal role in determining the core body temperature across varying environmental conditions by adjusting constriction/dilation rates and the velocity of circulation. As shown in Fig. 1b, within this framework, simulating this system in a humanoid cover fabricated from metal can enable the portrayal of a thermal infrared image similar to that of human skin, as presented in Fig. 1c. Notably, humans can discern subtle temperature variations at ~0.5 °C26,27. Thus, ensuring that a prosthetic or robotic hand aligns with human body temperature could eliminate the discomfort and reluctance during tactile encounters, such as handshakes.

In this study, we developed a flexible, elastic fiber that imitates blood vessels and uses water to regulate heat transfer and dispersion processes. The choice of water stemmed from its appreciable thermal conductivity of 0.604 W/m K at 21.11 °C, surpassing other common temperature regulating fluids such as glycerin, ethylene glycol, and engine oil; these fluids have conductivities of 0.289, 0.249, and 0.145 W/m K, respectively. The artificial skin was created using silicone rubber and reflected the thermal conductivity attributes of human skin. This provided an essential base layer over the organized blood vessel-mimicked fibers for our experiments. A central component of this research was the precise control of heat originating from the fibers positioned beneath the silicone rubber layer. This was achieved by meticulously managing the water temperature and flow rate. As a result, we successfully recreated and maintained a thermal environment similar to that of the human body on thermoregulation artificial skin, marking a landmark development in biomechanical engineering.

Fabrication of blood vessel-mimicked fiber and control of heat dissipation characteristics

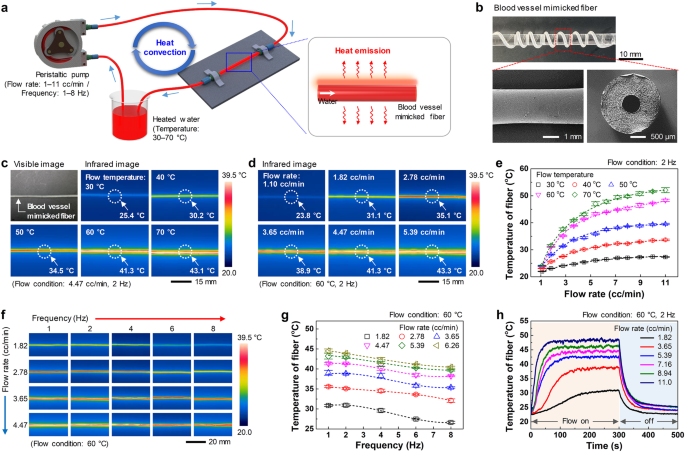

We designed a circulatory system that simulates the thermoregulatory processes of the human heart and blood vessels. This system includes a peristaltic pump, heated water, and fibers resembling blood vessels, as depicted in Fig. 2a. The peristaltic pump operates in a manner similar to the human heart, directing the flow of water, with the heated water serving as a heat transfer medium, analogous to blood in humans. This pump facilitates control of both the flow rate and the pulse frequency of the heated water directed to the blood vessel-mimicked fiber. The fiber, with an estimated diameter of 2 mm, is designed to mimic a blood vessel and contains a hollow core with a diameter of ~500 μm, as shown in Fig. 2b. Given that human blood vessels frequently constrict and dilate for optimal heat regulation, the fiber designed to simulate this was crafted from a flexible silicone material, ensuring that it could accommodate these dynamic changes. The resulting fiber exhibited mechanical properties with ~700% strain and stress of 1.2 MPa upon reaching its rupture point, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

a Schematic of the water flow regulation within the fiber. b Photographic and FE-SEM images of the fabricated fiber. c, d Infrared images and e temperature graphs corresponding to changes in the water temperature and flow rate. f Infrared images and g temperature graphs related to changes in the water flow rate and frequency. h Time-dependent temperature graph corresponding to water flow activation and deactivation.

We carefully regulated the temperature, flow rate, and frequency of water flowing through the fiber-imitating blood vessels to control its heat dissipation intensity. The most direct approach to regulate the fiber’s temperature was the adjustment of the internal water temperature. Figure 2c illustrates the temperature fluctuations in the fiber in relation to the variations in the internal water temperature, maintaining consistent flow rates and frequencies at 4.47 cc/min and 2 Hz, respectively. As the water temperature increased from 30 to 70 °C, the temperature of the fibers increased from 25.4 to 43.1 °C. Figure 2d illustrates that, maintaining a water temperature of 60 °C and a frequency of 2 Hz, the temperature of the fibers climbed from 23.8 to 43.3 °C as the flow rate varied between 1.10 and 5.39 cc/min. Figure 2e graphically depicts the fiber temperature reactions at various water temperatures (30–70 °C) and flow rates (1.10–11.0 cc/min). These findings indicate that the fiber temperature is directly proportional to increases in both the water temperature and flow rate. However, a significant increase in the water temperature (a 40 °C increase from 30 to 70 °C) resulted in a more moderate temperature increase in the fibers (an ~24 °C increase from 27.3 to 51.1 °C), under flow rates of 11 cc/min and 2 Hz. This behavior can be understood through Fourier’s law of heat conduction, which states that heat transfer is amplified with greater temperature differences and that higher temperatures result in increased heat loss. The relevant equation is shown below:

where ΔQ denotes the heat transfer, Δt represents the time change, k represents the thermal conductivity, ΔT is the temperature gradient between the two entities, A is the cross-sectional area in contact, and x denotes the distance. Fundamentally, as the temperature of the internal water rises, the subsequent heat loss intensifies. This manifests in a growing disparity between the temperature of the water and that of the fiber, with differences of 2.7, 6.3, 10.5, 11.7, and 17.9 °C corresponding to the paired water and fiber temperatures of 30/27.3, 40/33.7, 50/39.5, 60/48.3, and 70/52, respectively. Furthermore, the temperature of heated water tends to decrease as it passes through fibers resembling blood vessels. As water resides within the fiber for a longer time, the heat dissipation becomes more pronounced. Hence, an increased flow rate accelerates the entry and circulation of the heated water via the peristaltic pump, minimizing the time the heated water stays within the fiber, with subsequent cooling. This culminates in an increase in the temperature of the fiber, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Notably, even when the water temperature remains consistent, adjustments to the flow rate can modulate the fiber temperature.

Figure 2f, g displays thermal infrared images and a corresponding temperature chart, respectively, revealing the degree of heat dissipation within the fiber as dictated by the flow frequency of the internal water. Altering the frequency while retaining a uniform flow rate results in a variable volume of water being infused into the fiber per cycle. At higher frequencies, smaller water volumes are more frequently introduced, while at lower frequencies, a greater volume is less frequently introduced. For example, with a flow of 4.47 cc/min at 1 Hz, ~0.075 cc of water is infused 60 times per minute. In contrast, at a flow of 4.47 and a frequency of 8 Hz, ~0.009 cc of water is remarkably infused 480 times per minute. With increasing frequency, a corresponding gradual decrease in the temperature of the fiber mimicking a blood vessel is observed. At a 60 °C flow rate of 4.47 cc/min, the fiber temperatures were ~41.4, 41.3, 40.2, 38.5, and 38.3 °C for frequencies of 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 Hz, respectively. At a 60 °C flow rate spanning from 1.10–11.0 cc/min and with frequency variations from 1 to 8 Hz, the average alteration in fiber temperature was −3.3 ± 0.59 °C, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. These results confirmed the feasibility of finely tuning the temperature of the fiber simulating a blood vessel through meticulous management of flow frequency.

Figure 2h depicts the time-dependent temperature variations of the fiber resembling a blood vessel, based on the activation or deactivation of the water flow. Both the water temperature and frequency were maintained at 60 °C and 2 Hz, respectively. Upon initiating water circulation, the temperature of the fiber promptly increased. A significant observation was that an increased flow rate expedited the peak temperature of the fibers, and the temperature then stabilized. Following the cessation of water circulation, the temperature swiftly decreased, settling at ~25 °C after 100 s.

Within the realm of human physiology, when the core body temperature drops below 37 °C, the hypothalamus, which is responsible for thermoregulation, triggers arteriolar vasoconstriction via the sympathetic nervous system. This action reduces blood flow to the skin, thereby minimizing temperature loss through radiation and convection. Conversely, if the body temperature surpasses 37 °C, the hypothalamus induces vasodilation, increasing blood flow to the skin and subsequently enhancing heat dissipation (Fig. 3a)23. Translating this to vascular heat dissipation dynamics is as follows: vasoconstriction is synonymous with decreased heat loss, whereas vasodilation intensifies he heat loss.

a Human heat modulation via vasodilation and vasoconstriction. b Photographic evidence of the changes in the fiber volume over time. c Schematic of the flow rate and d graph showing the interplay between the fiber volume and temperature with frequency variations.

The selected material for the fiber simulating a blood vessel, silicone rubber, possesses notable elasticity. When water flows through the fiber, it induces internal pressure, causing the fiber to dilate (Fig. 3b). Figure 3c shows the volume changes relative to the internal water flow rate of the fiber simulating a blood vessel (as noted in Supplementary Video 1). At a flow rate of 11 cc/min, a maximum volume fluctuation of 3.5% was observed (operating conditions: 60 °C, 2 Hz). Notably, the temperature of the water had no impact on the volume changes. Torricelli’s theorem elucidates the relationship between flow rate and pressure:

where (v) is the flow rate, g represents gravitational acceleration, P is the pressure, and ({varUpsilon }) represents the specific gravity. Apparently, an increase in the flow rate leads to a quadratic rise in pressure. Modifying the frequency while sustaining a uniform flow rate results in varying volumes of water being introduced per cycle, thereby adjusting the internal pressure. Elevated frequencies lead to smaller water volumes more frequently introduced, resulting in a decrease in the internal pressure. As illustrated in Fig. 3d, under operating conditions of 60 °C and 5.39 cc/min, the volume change of the fibers decreased from 1.9 to 1.3% as the frequency increased from 1 to 8 Hz (refer to Supplementary Fig. 4). Concurrently, the temperature of the fiber decreased from 43.2 °C (at 1 Hz) to 40.0 °C (at 8 Hz). Hence, by controlling the extent of dilation in the fiber simulating a blood vessel, similar to the physiological processes of vasoconstriction and vasodilation, heat dissipation can be effectively modulated.

Similar to the positioning of blood vessels beneath human skin for temperature regulation, silicone rubber simulates the role of skin by covering the fiber that mimics a blood vessel, creating a synthetic skin with thermoregulatory properties. The thermal conductivity of silicone rubber is ~0.2 W/m K28, which closely parallels the thermal conductivity of human skin at 0.21 W/m K29. The thermal infrared temperature and distribution within this synthetic skin are determined by its thickness and the organization of the underlying fibers that resemble blood vessels. The thermal characteristics of synthetic skin in relation to its thickness and the thermal interference effects resulting from the arrangement of the fibers need to be elucidated to accurately reproduce the thermal infrared temperature and distribution observed in human planar skin.

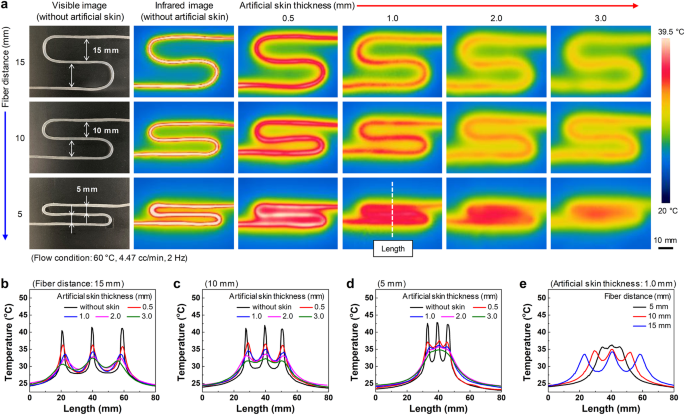

Properties and applications of thermoregulation artificial skin

Figure 4 illustrates the thermal infrared temperature and distribution patterns of the thermoregulatory artificial skin; these patterns are dependent on the skin’s thickness and the arrangement of the fibers mimicking blood vessels (operating conditions: 60 °C, 4.47 cc/min, 2 Hz). The thermal infrared temperature and distribution of the fibers positioned beneath the thermoregulatory artificial skin were analyzed on the surface of the skin. The 80 × 80 mm2 artificial skin segment, composed of silicone rubber, had varying thicknesses: 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 mm. To study the thermal dynamics, a single 400-mm-long fiber was designed in a serpentine pattern and underwent spacing adjustments at 15, 10, and 5 mm intervals (Fig. 4a).

a Photographic and thermal infrared images displaying differences based on the skin thickness (none, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 mm) and fiber spacing (5, 10, 15 mm). b Temperature patterns related to the skin thickness (none, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 mm) at 15 mm fiber spacing, followed by profiles at c 10 mm and d 5 mm intervals. e Temperature patterns for a 1.0 mm skin thickness adjusted by fiber spacing (15, 10, 5 mm).

Heat radiating from the fiber resembling a blood vessel spreads radially, moving from the base to the surface of the artificial skin. As a result, an increase in the thickness of the synthetic skin leads to a noticeable reduction in its thermal temperature. In addition, the representation of the fibers in the thermal distribution images becomes increasingly blurred (Fig. 4b–d). Reduced spacing between the fibers amplifies the thermal interference effect, leading to a temperature increase in the sections of the synthetic skin situated between the fibers (Fig. 4e). Based on the thermal infrared images, an even temperature distribution arises when the fiber spacing is limited to 5 mm and the thickness of the synthetic skin is 1.0 mm or greater.

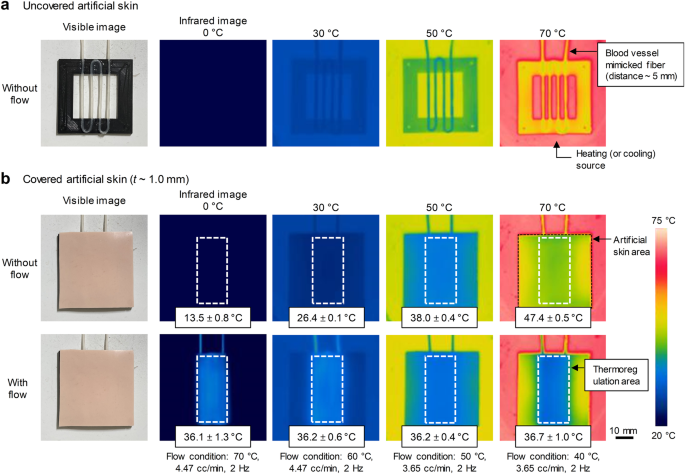

Prosthetic hands and humanoid robots fitted with thermoregulatory artificial skin contain numerous semiconductor devices and actuating components. These elements can generate localized heat. Our study examined conditions where a thermal temperature close to 36.5 °C, similar to that of human skin, can be consistently maintained, even in the presence of indirect heat sources. A square frame measuring 2 mm in thickness and covering an area of 40 mm2 was placed over either a heating source (with temperatures of 30, 50, or 70 °C) or a cooling source set at 0 °C. Centering this frame, within a 25 mm2 space, a fiber imitating a blood vessel was arranged in a serpentine pattern, with 5 mm intervals between each loop, as shown in Fig. 5a. This configuration was subsequently enveloped by an artificial skin layer that was 1 mm thick and spanned an area of 40 mm2, as illustrated in Fig. 5b.

a Photographic and thermal infrared images of the fibers arranged in serpentine patterns at 5 mm intervals. b Images of the artificial skin covering the structured fibers, both with and without water circulation.

After the assembly was allowed to sit for 5 min without any water circulation, the registered temperatures on the artificial skin were 13.5 ± 0.8, 26.4 ± 0.1, 38.0 ± 0.4, and 47.4 ± 0.5 °C, corresponding to source temperatures of 0, 30, 50, and 70 °C, respectively. Evidently, the temperature of the artificial skin is influenced by the thermal conditions of the source below it. However, by initiating water flow through the fiber that simulates a blood vessel under specific flow conditions, we stabilized the temperature of the artificial skin near the optimal temperature of 36.5 °C. Within the artificial skin’s surface, the areas directly above the fiber, which were the primary sites of thermoregulation, were clearly identifiable (marked by a white dotted-line perimeter).

Using a cooling source at 0 °C, the thermoregulated area maintained a temperature of 36.1 ± 1.3 °C under flow conditions of 70 °C, 4.47 cc/min, and 2 Hz. When the heating source was set to temperatures of 30, 50, and 70 °C, the temperatures of the thermoregulated area were 36.2 ± 0.6, 36.2 ± 0.4, and 36.7 ± 1.0 °C, respectively, under their specific flow parameters.

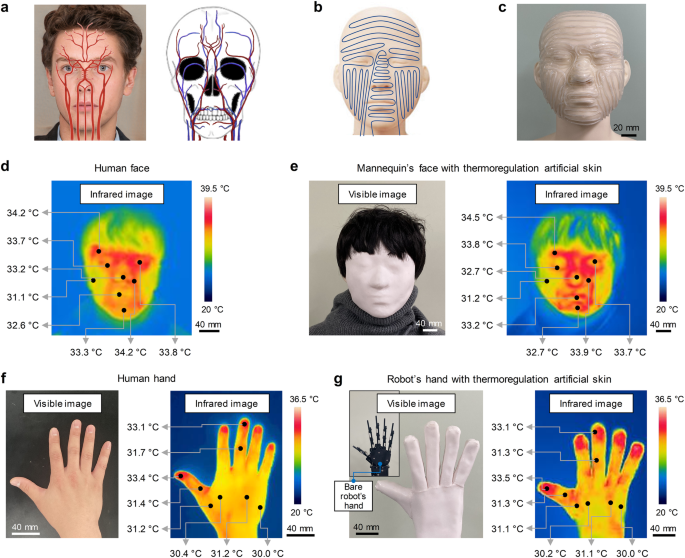

Human skin contains a complex network of blood vessels responsible for distributing heat, oxygen, and nutrients throughout the body. Figure 6a shows a depiction of the primary blood vessels distributed across the human face. To simulate the thermal infrared temperature and distribution of a human face, six segments of fibers mimicking blood vessels were arranged on a mannequin’s face, as illustrated in Fig. 6b, c. These fibers were then covered by the specifically designed artificial skin, creating a thermoregulatory layer for the mannequin’s facial region. These fibers were connected to two peristaltic pumps to facilitate the circulation of heated water, and each pump managed three fiber segments.

a Prominent blood vessel structure on the human face. b Conceptual illustration of the fiber positioning on a mannequin’s face. c Photograph of the fibers on an actual mannequin’s face. d Infrared patterns on an authentic human face. e Photographic and thermal infrared images of a mannequin’s face fitted with thermoregulation skin. Photographic and thermal infrared images of (f) a real human hand and g a robot’s hand fitted with thermoregulation skin. The image of the face shown in (a) was produced using a digitally processed virtual face.

An infrared image captured using an infrared camera showed the temperature distribution across an actual human face (Fig. 6d). Notably, higher temperatures were observed around the eyes, nose, and mouth than in cooler regions of the cheeks. The temperatures recorded around the eyes and nose were ~34.2 °C, while the cheeks remained relatively cool at 31.1 °C. Figure 6e shows both conventional and thermal infrared images of the mannequin’s face equipped with thermoregulatory skin. The fibers mimicking blood vessels were strategically arranged: three segments surrounding the eyes, lips, and chin with spacings ranging from 1 to 3 mm and another three segments traversing the cheeks, eyes, nose, and lips, spaced 4 to 5 mm apart. By circulating water at temperatures of 54 and 52 °C at specific flow rates through these fibers, certain facial regions, particularly around the eyes and nose, exhibited relatively high temperatures, at ~34.5 and 33.9 °C, respectively (as noted in Supplementary Fig. 5). In contrast, the cheeks remained cooler at ~31.2 °C.

Figure 6f shows both conventional and thermal infrared images of a human right hand; here, the extremities, especially the fingertips, are warmer than the dorsal (back) region of the hand. Specifically, the thumb and middle fingertips had temperatures of 33.4 and 33.1 °C, respectively, while the dorsal region remained cooler, with temperatures between 30.0 and 31.2 °C. Figure 6g shows a comparison between the thermoregulatory skin on a robotic hand and the thermal distribution of a human hand. Without the thermoregulatory skin, the robotic hand did not produce discernible infrared radiation (as noted in Supplementary Fig. 6). To simulate the infrared temperature and distribution consistent with a human hand, a thermoregulatory skin comprising nine segments of the blood vessel-mimicking fibers was crafted and attached to the robot hand. Two fibers were designated for the thumb, while the remaining fingers received one fiber each, spaced between 1 and 4 mm apart. On the dorsal side, three fiber segments were distributed at intervals between 2 and 5 mm (as noted in Supplementary Fig. 7). Water was heated to predefined temperatures and directed through these fibers at established flow rates, and the thermoregulatory skin on the robotic hand effectively mirrored the thermal distribution of a human hand. The temperatures of the thumb and middle fingertips were ~33.5 and 33.1 °C, respectively, while those of the dorsal hand ranged between 30.0 and 31.1 °C.

Conclusion

In summary, we developed a thermoregulatory artificial skin that replicated the thermal infrared temperatures and distributions found in human skin, and its application was targeted for humanoid robots and prosthetic hands. Our approach simulated the crucial components of the human circulatory system, including the heart and vascular network. We represented blood vessels using fibers mimicking their structure; these fibers were made of elastic silicone material with a hollow configuration measuring a diameter of 500 μm. Since water acted as the heat medium, it was circulated through these fibers using pumps that operated under various conditions. These conditions covered temperature intervals of 30–70 °C, flow rates from 1.10 to 11.0 cc/min, and frequency variations between 1 and 8 Hz to observe the resultant thermal attributes on the fiber surface.

In parallel with the temperature regulation performed by the human heart through blood circulation, we adjusted the temperature of the mimicked fibers by modifying the water flow rates. The use of 60 °C water with flow rates ranging from 1.10 to 11.0 cc/min allowed the fiber temperatures to range between 23.8 and 48.3 °C. More nuanced temperature control was achieved by adjusting the fiber’s dilation, reminiscent of the arteriole’s vasoconstriction and vasodilation mechanisms. By introducing water at 60 °C with a flow rate of 5.39 cc/min and frequencies between 1 and 8 Hz, we observed fiber volume changes between 1.9% and 1.2%, which correlated with temperatures ranging from 43.2 to 40.0 °C.

To complete the design, we constructed an artificial skin layer from silicone rubber, which possessed a thermal conductivity of 0.2 W/m K, similar to that of human skin. We then assessed the thermal infrared temperature and distribution properties of this thermoregulatory artificial skin, considering variances in the skin thickness (0.5–3.0 mm) and the spacing between the fibers at the base of the artificial skin (5–15 mm). The successful integration of this innovative skin on a mannequin’s face and a robot’s hand effectively simulated the thermal infrared temperatures and distributions observed in humans, highlighting its practical application potential. Although problems with the miniaturization and power supply of water circulation systems using peristaltic pumps need to be addressed, thermoregulation artificial skin represents a significant milestone in the rapidly advancing field of robotics. This skin provides a solution to minimize the subtle discomfort felt during human–robot interactions, thereby promoting a smoother integration of robotic technology into everyday human tasks and providing a more harmonious coexistence.

Responses