Altermagnetism, piezovalley, and ferroelectricity in two-dimensional Cr2SeO altermagnet

Introduction

Spintronics has witnessed remarkable advancements through the discovery and development of novel magnetic materials. These materials play a crucial role in controlling spin-dependent phenomena and enabling the design of next-generation electronic devices1. Traditionally, spintronics research has been dominated by ferromagnets and antiferromagnets, each offering distinct advantages in terms of spin manipulation. However, the emergence of a new class of materials, known as altermagnets has introduced an innovative paradigm that bridges the gap between these two well-established categories2,3. Altermagnets are distinguished by their unique spin-splitting properties that are not governed by conventional exchange interactions but instead arise from an unconventional symmetry-driven mechanism4. This class of materials is characterized by alternating spin polarization in reciprocal space while maintaining a zero net magnetization, thus combining the advantages of both ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic systems3,5. Furthermore, altermagnets exhibit intriguing electronic behaviors, such as spin-dependent transport6, Berry curvature effects7, and the potential for valleytronics8, which make them promising candidates for advanced quantum devices.

Recent studies have identified a range of candidate materials exhibiting altermagnetic characteristics, including certain transition metal oxides and Janus 2D materials such as V2Se2O9, V2SeTeO5,10, Cr2SO11, and RuO212. The distinct symmetry in these materials and electronic structure enables the realization of altermagnetic phenomena, offering an innovative approach to spin manipulation in low-dimensional systems. Moreover, external perturbations such as strain10, doping13, and electric fields14 provide additional tunability, paving the way for multifunctional devices. Recently, the spin-valley-locking was investigated in V2Se2O and Cr2O29,15. This spin-valley-locking was protected by crystal symmetry through a mechanism termed C-paired spin-valley-locking (SVL) rather than the spin-orbit coupling (SOC) and time reversal symmetry-dependent mechanisms9,15,16. This protection underscores the robustness of these valley properties in the altermagnetic material. It was also claimed that valley polarization could be obtained in the V2SeTeO Janus monolayer with the piezo effect5. Motivated by this, we propose the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer (based on the pristine Cr2O2) as a promising candidate material for achieving symmetry-driven spin-valley phenomena and tunable electronic properties.

Besides, the coexistence of altermagnetism and ferroelectricity (so-called multiferroics) in a single material may bring significant attention. Understanding the intricate interplay between altermagnetic and ferroelectric orders can open up avenues for designing materials with tailored magnetic and electric properties for next-generation spintronic and multiferroic devices. Ferroelectricity (FE) refers to the phenomenon that spontaneous electric polarization can be reversed by an external electric field. The first prediction of the FE in 2D was in the graphanol17. Subsequent theoretical studies proposed various 2D FE materials; phosphorene analogs such as (GeS, GeSe, SnS, and SnSe)18, (SbN and BiP monolayers)19, and Janus BMX220 structures. Among these, layered indium selenide (QL-In2Se3) has garnered significant attention due to its in-plane (IP) and out-of-plane (OOP) ferroelectricity21,22. The experimental realization of 2D FE was achieved in 2016 with thin-layer SnTe23 and CuInP2S624. Regarding the FE of altermagnet, Smejkal et al. proposed that a bulk type CaMnO3 could be ferroelectric altermagnetic2 material. However, no explicit calculation for spontaneous polarization was reported. Moreover, no reports are available on the coexistence of altermagnetism and FE in 2D material. Therefore, in this report, we aim to explore the magnetic and piezovalley related properties of altermagnetic material. Besides, the Janus Cr2SeO possesses the broken out-of-plane mirror symmetry. Due to this structural feature, we also investigated the possibility of ferroelectricity in the Cr2SeO altermagnet, despite the lack of the centrosymmetric structure in this Janus system, where we proposed an approximated method to estimate the value of the spontaneous polarization. This dual functionality not only expands the landscape of valleytronics research but also opens new avenues for the design and development of multifunctional devices with integrated valley polarization and ferroelectricity.

Results

Structural and physical properties

Figure 1a shows the structural illustration with top and side views of the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer. Note that the Cr2SeO monolayer consists of three sublayer atomic structures with the Cr atom as the central sublayer sandwiched by the O and Se planes. In comparison with the pristine Cr2O2 monolayer (space group number 123, P4/mmm), the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer (space group number 99, P4mm) exhibits lower symmetry due to out-of-plane mirror symmetry breaking showing the tetragonal structure and in-plane C4v symmetry. Besides, the Cr2SeO monolayer has lattice parameters of a = b = 3.72 Å. These lattice constants are slightly larger than those reported for the pristine Cr2O2 monolayer (3.37 Å) owing to the Se atom effect. After relaxation of the crystal structure, we calculate the formation energy of monolayer Cr2SeO by using the following relation,

where ET, ECr, ESe, and EO represent the total energy of the system, the chemical potential of the Se atom, the chemical potential of Cr, the chemical potential of Se, and the chemical potential of O, while N is the total number of atoms per cell. The calculated formation energy is -1.29 eV/atom. The negative sign shows that the isolated Cr2SeO monolayer is thermodynamically stable. Furthermore, we also confirm the dynamical stability of monolayer Cr2SeO by calculating the phonon dispersion spectrum, and the result is displayed in Fig. 1b. We find no imaginary frequencies in the phonon dispersion spectrum over the whole Brillouin zone. Also, the thermal stability is checked using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and Fig. 2a–d shows the top and side views of the crystal structures. We find that the crystal structures are preserved at 200 K, 250 K, and 280 K. However, the crystal structure is slightly distorted at 300 K.

a Top and side view of the optimized crystal structure of Janus Cr2SeO monolayer and (b) phonon band structure of Janus Cr2SeO monolayer.

Top and side view of the crystal structures of the Cr2SeO monolayer after molecular dynamic simulations at (a) 200 K, (b) 250 K, (c) 280 K, and (d) 300 K.

Magnetic, electronic, and valley-related properties

Next, we explore the magnetic ground state of the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer by calculating the energy difference (ΔEex) between the antiferromagnetic (AFM) and ferromagnetic (FM) states (ΔEex = EAFM-EFM) in the unit cell. The Cr2SeO monolayer favors an AFM configuration with an energy difference of ΔEex = −0.86 eV. The net magnetic moment in the system has zero value, whereas the magnitude of the magnetic moment of each Cr atom is around 3.55 μB. However, the Se and O atoms have each a 0.026 µB and -0.026 µB contribution to the total magnetic moment. Moreover, we also investigate the electronic band structure. Figure 3a shows the spin-polarized band structure of the Cr2SeO monolayer. The blue and red colors represent the spin-up band and spin-down bands. The Cr2SeO monolayer has a direct band gap of 0.60 eV, and the opposite spin bands appear in the Γ-X and Γ-Y directions. This characteristic indicates the altermagnetic feature. Indeed, the most noticeable feature is a band inversion in the conduction band minimum (CBM) and valence band maximum (VBM) at specific high symmetry points namely X or Y. For instance, the spin-down band appears in the VBM near the Y-point, and the spin-up band is observed in the CBM at the same Y-point. Near the X-point, we find the opposite behavior. This is owing to the local lattice distortion in the Janus layer. In the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer, the bond length of Cr-O is 2.15 Å (Cr-O-Cr angle is 120.45°) while that of Cr-Se is 2.58 Å (Cr-Se-Cr angle is 92.35°). Due to this, there are different superexchange interactions between Cr-O-Cr (on the upper side) and Cr-Se-Cr (on the lower side). This, in turn, gives rise to the band inversions in the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer. To elucidate the influence of the local lattice distortion on the spin inversion band, we consider the pristine Cr2O2 monolayer and simply replace one of the O atoms with a Se atom as shown in Fig. 3b Since the structure relaxation is not considered after replacing O with Se, the system has no local lattice distortion (namely, an artificial Cr2SeO system). Figure 3c shows the calculated band structure, and we find no band inversion at Y and X high symmetry points. Therefore, we attribute the local lattice distortion to the band inversion. Despite the band inversion at the Y and X high symmetry points, the valley energies E(Y) and E(X) are degenerated due to the diagonal mirror symmetry. Consequently, we obtain no valley polarization in the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer. Indeed, the valley polarization in the Cr2SeO is the crystal symmetry-related valley (C-paired valley) as reported by Ma et al. 9 and is different from the conventional valley polarization owing to the time-reversal symmetry-related valley (T-paired valley)25. This means that the uniaxial strain along the in-plane axis (a- and b-direction) can break the lattice symmetry and produce valley polarization in the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer. Therefore we apply a uniaxial tensile and compressive strain ranging from +4% to -4%. Figure 4a, b shows the valley polarization as a function of uniaxial strain along in-plane a- and b-directions. Firstly, with uniaxial strain, the degeneracy is broken, and the valley polarization (P) is obtained. Note that the valley polarization is defined by the energy difference between two high symmetry points; P = E(Y) – E(X). The valley polarization increases with compressive and tensile strains in both valence and conduction bands along both a- and b-directions. However, we observed an opposite trend along the a- and b-directions under compressive and tensile strain due to the diagonal mirror symmetry in the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer. Interestingly, a maximum valley polarization of 90 meV is obtained in the valence band under the uniaxial compressive strain of -4% in the a-direction as shown in Fig. 4a. This value is larger than that found in the V2Se2O monolayer (~60 meV)9, Janus VSCl monolayer (57.8 meV)26, and is comparable to the value found in the Janus V2SeTeO monolayer (~100 meV)5. Furthermore, the band gap shows similar variation with uniaxial compressive and tensile strain along the a- and b-directions as shown in Fig. 4c.

a Spin-polarized band structure with Brillouin zone as inset for Janus Cr2SeO monolayer, (b) crystal structure of pristine Cr2O2 and artificial structure of Cr2SeO after replacing one O with Se in Cr2O2 monolayer without relaxation, and (c) spin-polarized band structure of artificial Cr2SeO crystal structure in (b).

a Valley polarization as a function of uniaxial strain along (a) a-direction, (b) b-direction, and (c) change in band gap as a function of strain in Cr2SeO system.

Magnetocrystalline anisotropy and Neel temperature

We also investigate the magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy (MAE) of the Cr2SeO monolayer using the non-collinear total energy calculations including the spin-orbit coupling (SOC). The Cr2SeO monolayer has an in-plane anisotropy in the [100] direction, and the calculated MAE is -0.28 meV/cell which is higher compared to that found in Cr2SO (-0.186 meV/cell)11. To understand the in-plane anisotropy, we analyze the (SOC) matrix elements of Cr, Se, and O atoms. Figure 5a–d shows the calculated results. Here, the out-of-plane anisotropy is represented by positive values while the in-plane anisotropy is denoted by the negative values. In a unit cell, there are two Cr, one Se, and one O atom. In the Cr1 atom, the SOC between dx2-y2 and dxy originate out-of-plane contribution which is compensated by the in-plane contribution from SOC between dz2 and dyz orbitals as shown in Fig. 5a. Thus, we have a negligible in-plane contribution from the Cr1 atom. On the other hand, the Cr2 atom has a dominant contribution to in-plane anisotropy, which originates from the SOC between dz2 and dyz orbitals as shown in Fig. 5b. Note that both O and Se atoms have no meaningful contribution to the total MAE as shown in Fig. 5c, d. We also estimate the Neel temperature by calculating the temperature-dependent sub-lattice magnetization (n(T)). Herein, we utilize the Heisenberg spin Hamiltonian with single-ion anisotropy as,

a Atomic resolved magnetic anisotropy energy (MAE) for (a) Cr1, (b) Cr2, (c) O, and (d) Se atoms in Janus Cr2SeO monolayer. e Temperature-dependent sublattice magnetization (TN) of the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer and (f) Temperature-dependent sublattice magnetization (TN) of 1% compressive Cr2SeO monolayer.

Here, Jij represents the exchange interaction between atoms at sites (i and j), while Si and Sj represent the spin moment direction of atoms at neighboring sites (i and j). Besides, ku, nα, Nα, and Si represent the single ions anisotropy, an average of one sublattice magnetization, number of atoms in the sublattice, and magnetization of the atoms at the ith site. Although the total magnetization is zero in the AFM state, the magnetization of the two sublattices is equal in magnitude and opposite in signs. To calculate the exchange interaction ({J}_{{ij}}=frac{{E}_{{exc}}}{N{m}^{2}}), we calculate the exchange energy difference (Eexc) between FM and AFM configurations using first-principles calculations. Here, N and m are the number of magnetic atoms in the cell and the average magnetic moment. For calculating the temperature-dependent sub-lattice magnetization curve, a (100 × 100 × 1) supercell with 1,000,000 total time steps is considered. Figure 5e, f shows the temperature-dependent average sub-lattice magnetization n(T) curve with a black color line for pristine and 1% uniaxial compressive strained Cr2SeO monolayer. The red lines show the curve fitted using the Curie-Block equation (nleft(Tright)={left[1-frac{T}{{T}_{N}}right]}^{beta }). The pristine Cr2SeO has a Neel temperature of 280 K, and this is further enhanced to 315 K at 1% compressive strain.

Ferroelectric and piezoelectric properties

We now discuss the intrinsic ferroelectricity of this system. Typically, the traditional ferroelectric materials possess two stable polarization states that can be switched from one to the other by applying an electric field. For example, Pb(Zr, Ti)O3 (PZT) has two stable polar states with the same energy and magnitude of polarization27. However, more complex behaviors have been identified in recent research. In 2021, Warusawithana et al. observed asymmetric ferroelectricity in engineered crystals made from oxide heterostructures by arranging the stacking order of molecular layers to break inversion symmetry and they discovered two unequal stable polarization states28. Moreover, in 2022 Meng et al. suggested the possibility of the existence of multiple polarization states in multilayer 3R MoS229. In addition, in 2023 Pang et al. reported a new nontraditional 2D ferroelectric material VInSe3 with two stable polar states exhibits a distinct energy and large out-of-plane spontaneous electric polarization30. While traditional ferroelectrics exhibit two equal states in the magnitude of polarization and energy, recent discoveries have expanded our understanding to include asymmetric states and even multiple polarization states in certain materials. These findings broaden the definition of ferroelectric materials.

The Cr2SeO Janus monolayer may exhibit ferroelectricity due to its unique polar structure, which arises from substituting an oxygen atom with selenium in the pristine Cr2O2, breaking its symmetry. The significant disparity in electronegativity between oxygen (3.44) and selenium (2.55) atoms results in a polar space group (P4mm) and a lack of inversion symmetry. While reflection symmetry vanished across the xy plane, it is maintained across the xz and yz planes. This lack of inversion and mirror symmetry facilitates charge transfer between adjacent atomic layers, creating an out-of-plane electric polarization, suggesting that the Cr2SeO Janus monolayer might exhibit out-of-plane ferroelectricity. We calculate the total electric polarization of the system along the z-axis by summing the electronic contribution with the ionic contribution, which was computed directly from the atomic positions and their effective charges. It is essential to note that this approach calculates the total polarization of the polar structure. However, without a non-polar reference structure (paraelectric), we cannot directly distinguish the spontaneous polarization from other contributions. However, for many ferroelectric materials, particularly those with significant polarization, the total electric polarization of the polar phase can serve as a reasonable estimate of the spontaneous polarization. According to the modern theory of electrical polarization, one can calculate the formal 2D polarization for a system using the following relation:

where (e) denotes the electron charge, (A) is the unit cell area, ({Z}_{a}) is the charge of the nucleus (a), ({u}_{n{bf{k}}}) are Bloch states are represented in a smooth gauge, ensuring that the k-space derivative is well-defined and the summation encompasses occupied states. The formal polarization is only defined modulo (e{R}_{i}/A), where ({R}_{i}) is an arbitrary lattice vector. This is because the nuclei positions can be selected in any unit cell, and ({R}_{i}/A) may alter the Brillouin zone integral due to a gauge transformation of the Bloch states. However, the polarization differences along any traditional ferroelectric path (TFP) are well defined, as it is possible to monitor the polarization along a specific branch. Consequently, the spontaneous polarization (Ps()) can be defined as:

where λ parameterizes a TFP between a non-polar reference structure (λ = 0) and the polar ground state (λ = 1).

Acknowledging the limitations of the lack of a non-polar reference structure for extracting the accurate spontaneous polarization according to the following formula: ({{P}_{s}=P}_{{polar}}-{P}_{{nonpolar}}), because the non-polar structure of Cr2SeO is not available we used the total electric polarization of the polar structure as an approximation of ({P}_{s}) implies that ({P}_{{nonpolar}}) is negligible or much smaller than ({P}_{{polar}}). So, we only consider ({{P}_{s}=P}_{{polar}}) in the present study.

The calculated total electric polarization of 5.34 pC/m represents our best estimate of the ferroelectric polarization in the Cr2SeO structure, The Ps value of monolayer Cr2SeO is comparable to those of bilayer binary compounds such as ZnO, SiC, double of bilayer h-BN31, and more than seven times higher than 1T-MoS2 (0.22 μC·cm−2)32. Furthermore, the spontaneous polarization of the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer is further increased to 5.52 × 10−12 C m−1 with a small uniaxial compressive strain of 1%. A robust out-of-plane spontaneous polarization (Ps) is highly needed to be compatible with contemporary top/bottom gate technologies and ferroelectric devices33.

Besides, the switching of electric polarization is crucial for ferroelectrics. Generally, it is hard to switch the electric polarization by an external electric field in Janus material. Thus, the Janus system is expected to be non-ferroelectric material. However, it has been reported that the switching path from -P to P can be possible without going through the centrosymmetric structure even in Janus layers. Nevertheless, the energy barrier for the transition seems very high, and it is unlikely to be switchable under realistic conditions34. In our Janus Cr2SeO monolayer, we compute the Born effective charges of Cr (3.87), Se (−1.48), and O (−2.91). These values provide valuable insights into the ferroelectric behavior of Cr2SeO, as the large positive value suggests that Cr atoms play a significant role in the ferroelectric behavior. For this reason, we observe that the polarization can be switched from 5.34 pC/m to -5.34 pC/m by a slight upward displacement (0.2 Å) of chromium atoms from the original z-coordinate without passing through an intermediate centrosymmetric structure following a nontraditional ferroelectric path (NTFP). The polarization as a function of energy in Fig. 6a shows that the polarization profile of Cr2SeO along NTFP differs from the typical profile determined by Landau-Ginzburg-Devonshire theory35 for a hypothetical traditional ferroelectric material with TFP. Both polar states of Cr2SeO exhibit equal magnitude and opposite signs of polarizations, while unequal energy states.

a Polarization as a function of total energy for (TFP and NTFP) and (b) Energy variations based on the switching step number in the NEB calculations for pristine and 1% uniaxial compressive strained Cr2SeO systems.

Figure 6b shows the energy barrier height obtained from the Nudged elastic band (NEB)36 calculations. Note that the NEB method provides us with a half-parabola energy profile, we then projected it symmetrically to obtain the other half to create the whole smooth symmetric parabola: the first branch from P to -P and the second branch from -P to P. Thus, Cr2SeO indicates consistent transition mechanisms in both directions. We found a low energy barrier of roughly 0.20 eV for 1% compressive strain compared with the unstrained structure (Eb = 0.23 eV). Note that the transition barrier height is lower than that found in VInSe3 (0.40 eV)30, LiSbO2 (0.47 eV)37, and Sc2CO2 (0.52 eV)38 although it is larger than that of the α-In2Se3 (0.05 eV)39.

Moreover, we investigated the stability of ferroelectricity to explore the critical temperature in Cr2SeO, we performed the MD simulations. Following MD simulations at 280 K (Fig. 2), most of the O and Se ions remain on the upper and lower side of the Cr ions, hence the structure still preserves the ferroelectricity. When the temperature is increased to 300 K, the structure is disrupted and loses the ferroelectric order. Thus, the ferroelectric critical temperature (TC) of our pristine Cr2SeO monolayer is 300 K. Figure 7a–d shows the top and side views of the structures after MD simulations at 200 K, 300 K, 325 K, and 350 K under 1% uniaxial compressive strain. The structure remains intact up to 300 K and distorted at around 325 K under 1% uniaxial compressive strain. Thus, the critical temperature is enhanced to 325 K with 1% uniaxial compressive strain, suggesting that the Cr2SeO monolayer exhibits robust ferroelectricity at room temperature. It is worth emphasizing that the present study on ferroelectricity is by no means exhaustive. We have not attempted to find other switching pathways here but rather suggested a possible path that would enable more systematic future research into 2D ferroelectric materials. Again, we believe that there may be many additional materials that allow for a nontraditional switching pathway that does not involve a centrosymmetric state.

Top and side view of the crystal structures of the Cr2SeO monolayer after molecular dynamic simulations at (a) 200 K, (b) 250 K, (c) 280 K, and (d) 300 K in Janus Cr2SeO monolayer.

Finally, we explore the piezoelectric properties as well. Piezoelectricity is a well-known phenomenon of electromechanical coupling that can generate voltage under mechanical strain40. The piezoelectric stress ({e}_{{ijk}}) and strain ({d}_{{ijk}}) tensor can be used to describe the piezoelectric response of a material. They can be expressed as the sum of electronic and ionic contributions

where ({P}_{i}), ({varepsilon }_{{jk}}) and ({sigma }_{{jk}}) are the polarization vector, strain, and stress respectively. By using the Voigt notation, the in-plane strain and stress can be reduced to

The non-zero ({e}_{31})/({d}_{31}) means that only vertical piezoelectric polarization can be induced when uniaxial strain is applied. By solving Eq. (7), ({d}_{31}) can be obtained as follows,

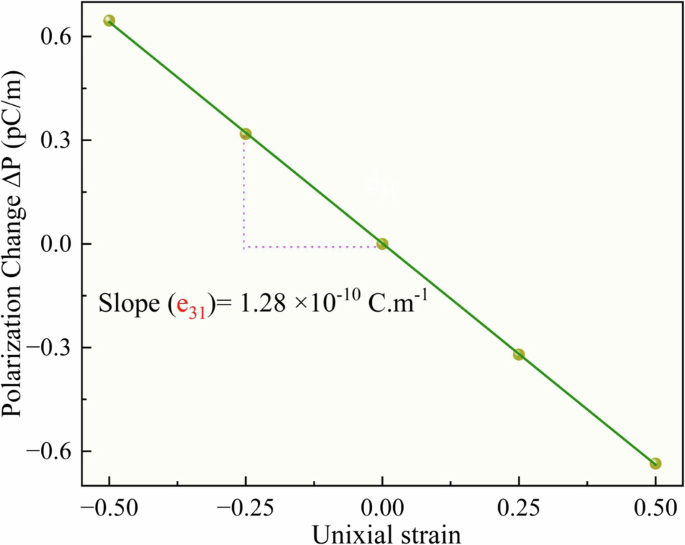

The elastic constants ({C}_{11}), ({C}_{12}), and ({C}_{66}) of Janus Cr2SeO are 82.51, 25.46, and 26.25 N/m respectively. These values meet the Born criterion for mechanical stability41: ({C}_{11},)> 0; ({C}_{66}) > 0; ({C}_{11}-{C}_{12} ,>, 0), and confirm the mechanical stability. Then, we determine the change in polarization along the z-direction per unit cell under a small uniaxial strain (−0.5 to +0.5). Figure 8 illustrates the direct calculations of the piezoelectric coefficient ({e}_{31}) for pristine Cr2SeO. The calculated ({e}_{31}) is 1.28 × 10−10 C.m−1. Thus, the ({d}_{31}) becomes 1.18 pm/V which is in accordance with previous report (1.17 pm/V)11. The ({d}_{31}) of the Cr2SeO is much higher than compared with that found in 2D materials; Cr2SO (-0.97 pm/V)11, h-BN (0.13 pm/V)42, oxygen functionalized MXenes (0.40–0.78 pm/V)43, 2D Janus Nanostructures M2AB (M = Si, Ge, Sn, A/B = N, P, As) (0.06–0.12 pm/V)44, WSiZ3H (Z = N, P, As) (0.15 pm/V) monolayers45, ferromagnetic CrSCl46, and NiClI (−1.58 pm/V) monolayers47. The large ({d}_{31}) maybe related to the large electronegativity difference of Se and O atoms. Indeed, the strong out-of-plane piezoelectric coefficient is preferable for piezoelectric cantilever and diaphragm devices with the d31 mode such as loudspeakers, microphones, and sensors48. The cantilever and diaphragm constructions can easily vibrate and create vertical piezoelectric polarization, which is suitable for bottom/top gate technologies.

Polarization changes as a function of Uniaxial strain for the 2D Janus Cr2SeO monolayer.

Discussion

In summary, we investigate the multifaceted properties of the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer, shedding light on its structural, magnetic, electronic, and ferroelectric characteristics. The calculated phonon dispersion spectra and MD simulations confirm the dynamical and thermal stability. Besides, the structure is also mechanically stable according to the Born stability criteria. The Janus Cr2SeO monolayer has an in-plane magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy of −0.28 meV/cell. The temperature-dependent sub-lattice magnetization reveals a Neel temperature of around 280 K, and this is further increased to 315 K under a 1% uniaxial compressive strain. We find that the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer possesses an antiferromagnetic ground state with distinctive spin band inversions along with large spin splitting of 0.38 eV at the Y and X high symmetry points. The pristine Cr2SeO monolayer has no valley polarization due to diagonal mirror symmetry. However, the uniaxial tensile and compressive strains break the diagonal mirror symmetry in the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer. This results in the valley polarization up to 90 meV. In addition to the strain-induced valley polarization (piezovalley), the application of uniaxial strain also tunes the bandgap significantly ranging from 0.30 eV under compressive strain to 0.76 eV under tensile strain. Moreover, the calculated total electric polarization of 5.34 pC/m represents our best estimate of the ferroelectric polarization in the pristine Cr2SeO monolayer, which is further enhanced to 5.52 pC/m with 1% uniaxial compressive strain. Also, the switching energy barrier is only 0.2 eV/unit cell. Note that our study on ferroelectricity is not exhaustive. Besides, a large vertical piezoelectric coefficient d31 of 1.18 pm/V is found in the Cr2SeO monolayer. Overall, our comprehensive studies propose that the Janus Cr2SeO monolayer can be utilized as a promising material for room-temperature multifunctional device applications such as valleytronics and ferroelectric memory devices.

Methods

Details of first-principles calculations

We perform comprehensive first-principles calculations using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) along with the projected augmented wave (PAW) method49,50. We use the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) for the exchange-correlation function51, and the on-site Coulomb interaction effect is included by using U = 3.55 eV for Cr-3d electrons11,16. We employ the plane wave energy cutoff of 600 eV with convergence criteria for total energy and force set at 10−8 eV and 0.001 eV/Å. We sampled the Brillouin zone with a k-mesh of 22 × 22 × 1, and a vacuum distance of 20 Å is applied along the c-axis to avoid artificial interactions between neighboring unit cells.

Phonon dispersion and ab initio molecular dynamics

To confirm the dynamical stability we calculate the phonon dispersion curve for the Cr2SeO monolayer using Phonopy code with the finite displacement method52. A 3 × 3 × 1 supercell with a k-mesh of 3 × 3 × 1 are considered. Furthermore, to check the thermal stability we calculate the ab initio molecular dynamics simulation using a Nose thermostat with NVT ensembles at different temperatures53. Here we consider a 2 × 2 × 1 supercell and a 6 × 6 × 1 k-point mesh.

Magnetic anisotropy, Neel temperature, piezoelectricity, and ferroelectricity

To calculate the magnetic anisotropy energy, we include the spin-orbit coupling (SOC) in a non-collinear spin configuration. The total energy difference is calculated between in-plane [100 and 010] and out-of-plane [001] magnetization directions. We estimate the temperature-dependent sub-lattice magnetization based on the Metropolis Monte Carlo simulations using the VAMPIRE software package54,55. To calculate the piezoelectric coefficients and ferroelectric properties (i.e. total electric polarization and energy barrier), we employed the Berry Phase method as implemented in the Quantum Espresso package56. Besides, the plane-wave code thermo_pw is used to calculate the elastic constants Cij57.

Responses