Chalcogen and halogen surface termination coverage in MXenes—structure, stability, and properties

Introduction

MXenes are a family of two-dimensional (2D) transition metal carbides, carbonitrides, nitrides, and oxycarbides that have emerged as versatile materials due to their unique combination of properties which hold promises for a wide range of potential applications1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Their composition is given by the general formula Mn+1XnTx, where M is a transition metal, X is typically carbon or nitrogen, and Tx represents the surface terminations. MXenes can have different numbers of M and X layers within its 2D unit, given by n that ranges from 1 to 4, with n + 1 M layers, interleaved by n X layers9. Tx includes elements from groups 16 and 17 of the periodic table as well as hydroxyl and imido groups (T = O, OH, NH, F, Cl, Br, S, Se, Te), and the terminations can be either single or mixed, depending on the synthesis process used10. Having control of the MXene composition, from Mn+1Xn to surface termination T and degree of surface coverage x, is essential for the MXene properties10,11,12,13,14. In the ideal case, corresponding to 100% surface coverage, x is equal to 2.

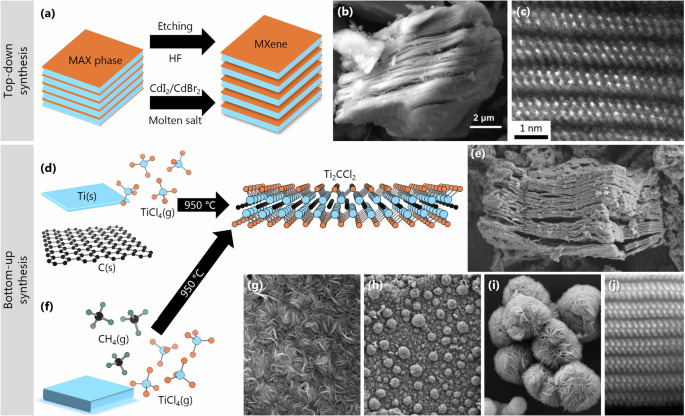

The very first MXene was discovered in 2011 when Naguib et al. reported Ti3C2Tx, using hydrofluoric acid (HF) for selective etching of monatomic Al layers from the Ti3AlC2 MAX phase precursor1. The etchant used will heavily influence the adsorbing termination species, where conventional etching in HF commonly results in O, OH, and F terminations1,15. MXene synthesis through selective etching of the A-layer (e.g., Al, Si, and Ga) in MAX phases is the common approach and includes etchants like HF1, ammonium bifluoride ((NH4)HF2)16 or mixtures of HCl/LiF17, HCl/KF18, and HF/H2O219. Other routes use different types of molten salts for selective etching of the A-layer in MAX phases and include Lewis acid molten salt (LAMS) etching10,13,20,21,22. Common for above listed MXene synthesis routes is that they rely on a precursor material, typically MAX phases, and can therefore be classified as top-down (Fig. 1a). This is in contrast to direct synthesis routes, classified as bottom-up, where the reactions of metals and metal halides with graphite, methane, or nitrogen allow for novel MXene compositions Mn+1Xn with ideal surface termination coverage23. Examples of bottom-up approaches include high-temperature reactions (Fig. 1d) and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) (Fig. 1f)23. The synthesis routes used will also impact the MXene morphology (Fig. 1b, e, g, h, and i) and, in turn, its properties.

a Schematics for etching MAX phases in HF or molten salts into multilayer MXenes. b SEM of Ti2CSx showing the typical accordion-like morphology of a MXene particle through molten salt-based etching of MAX phases. c High-resolution HAADF image of Ti2CSx along the [21̅1̅0] projection. d Schematics for direct synthesis of Ti and graphite powder with TiCl4 gas into Ti2CCl2. e SEM image of Ti2CCl2 MXene stack. f Schematic diagram of CVD reaction. SEM images showing g growth of uniform MXene carpet followed by h formation of “bulges” that further i developed into individual microspheres or spherical “vesicles”. j High-resolution HAADF image of the CVD-Ti2CCl2 along the [21̅1̅0] projection. Panels b, c, e, g, h, i, j from refs. 10,13,23. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

Having control of the MXene composition, from Mn+1Xn to surface termination T and the degree of surface coverage x, is essential for the MXene properties10,11,12,13,14. In the ideal case, x is equal to 2, corresponding to 100% surface coverage. Previous work has shown that O terminations can reach supersaturation with up to x ≈ 3.5 while maintaining the structural integrity of the MXene sheet24. Recent synthesis efforts have, on the other hand, demonstrated that x can be either 2 or <2, leading to non-ideal surface termination coverage depending on the synthesis route used10,13,25. The choice of termination and the degree of surface termination coverage could, in turn, enable MXenes to be tailored for specific applications, significantly expanding their utility through tuning properties, such as electrical conductivity, catalytic activity, mechanical properties, and hydrophilicity. Of importance for applicability is also the attainable MXene morphology, whether stacked in multilayers or delaminated into single sheets, where the latter, in some cases, comes with its challenges. Delamination in an aqueous solution of salts is possible, but control of the surface chemistry is limited by mixed and oxygen-containing terminations14,26. For halogen or chalcogen-terminated MXenes, the delamination is particularly challenging due to strong interlayer interactions between the Mn+1Xn sheets and the required use of hazardous chemicals, including n-butyllithium (n-BuLi) and sodium hydride (NaH)10,12,23. These are factors that may influence potential upscaling and practical applications. Proposed solutions to overcome such obstacles include the use of LiCl salt and anhydrous polar organic solvents27. To address these challenges, a first step is to increase the fundamental understanding of the MXene surface chemistry and resulting interlayer interaction, and to target pathways for tuning such interactions.

Of special interest in this work are halogen- and chalcogen-terminated MXenes, for which we have studied termination coverage from 100% (x = 2) to 50% (x = 1). Focus has been on both multilayer (ml) and single-sheet (ss) M2CTx, where M = Ti, Zr, V, Nb, Ta, and T = S, Se, Te, Cl, Br, I. This study systematically investigates deviation from ideal surface termination coverage in terms of the resulting structure, site preference for termination, defect energies, binding energies, and electronic properties. Our results demonstrate that for non-ideal termination coverage, x < 2, there is a blend of termination sites, with indications of tunable coverage down to x ≈ 1.33. We also find decreased binding energies for the ml-MXene with decreased surface coverage. However, too low termination coverage, especially for T = S, may lead to a collapsed structure, which gives rise to strong interlayer bonding that may hinder delamination.

Results and discussion

Experimentally reported multilayer MXenes with terminations from Groups 16 and 17

To date, there are numerous reports of multilayer MXenes with terminations from Group 16 (S, Se, Te) and 17 (Cl, Br). Table 1 gives an overview of M2CTx MXenes reported to date, their reported termination coverage x and structure, along with the synthesis method used for making them. Note that the elements include M = Ti, Zr, V, Nb, Ta, and T = S, Se, Te, Cl, Br, I. The termination coverage spans from x = 2, for which the MXene surface is fully covered (100%), to x ≈ 1, where only half of the surface is covered (50%). This can be correlated to the synthesis route used, where complete coverage (x = 2) is found for bottom-up synthesis of MXenes using CVD23 or sintering28,29 and for top-down synthesis using topochemical reactions29,30,31. MXenes with a termination coverage of less than 100% (x < 2) is typically found for MXenes synthesized via a top-down approach where the MAX phase reacts with molten salt10,13,25.

A few comments related to the ml-M2CTx MXenes found in Table 1 are motivated. The MXenes listed in the table represent those with M = Ti, Zr, V, Nb, and Ta experimentally reported to date with halogen and chalcogen terminations. There are several examples where the reference shows STEM images not necessarily compatible with the suggested crystal structure, such as for Ti2CTex, Ti2CSex, Ti2CSx, Ti2CBr2, and Ti2CCl210. Other examples include non-conclusive STEM images, or lack thereof, that are beneficial for determining the correct crystal structure, e.g., for Ti2CSx13, Ti2CClx10,23, Ti2CSex10, V2CSex13, Zr2CBrx23., Ta2CSex13, Ta2CTex13. Also important to note is the diverging focus on assessing the termination coverage, i.e., a stated full coverage may be an assumed approximation and does not have to necessarily reflect the true coverage.

From these observations, multiple questions arise. They concern whether the termination coverage x solely depend on the synthesis method used, or if it is possible to intentionally tailor specific values of x. Closely related to this is how different values of x will impact the preferred termination site, structure, properties, and the interlayer binding energy, all being covered in the present work.

To unravel how termination coverage may impact the interlayer interaction in multilayer MXenes and how different terminations and metal species interact within and in between MXenes layers, we will increase the complexity of this study stepwise. In the first part, we focus on ideal termination coverage, i.e., M2CT2, for various termination T, their preferred site, and how M2CT2 monolayers are stacked in the multilayer MXene. This will be followed by single sheet MXenes with ideal termination coverage. In the second part, we take a closer look at deviations from ideal termination coverage, i.e., when x < 2 for M2CTx, and its impact on structure and, more importantly, on the interlayer interaction in multilayer MXene and resulting electronic properties. We also consider the effect of O terminations replacing the missing chalcogens and halogens in case of non-ideal coverage. Finally, an analysis of mechanical properties is performed for single-sheet MXenes with ideal surface termination coverage.

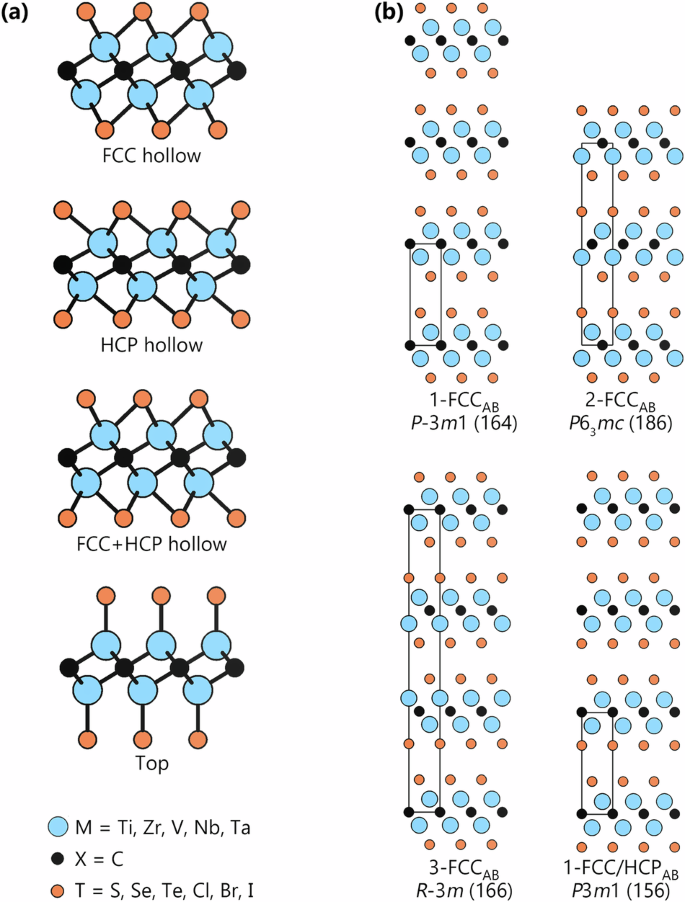

Modeling multilayer MXene with ideal termination coverage

In total, six termination species (S, Se, Te, Cl, Br, and I) interacting with five MXenes (Ti2C, Zr2C, V2C, Nb2C, and Ta2C) were considered. For each of the 30 M2CT2 combinations, we have considered four termination sites illustrated in Fig. 2a—three hollow sites denoted as FCC, HCP, and a combination of FCC and HCP, and one denoted as Top. Moreover, for ml-MXenes it is also necessary to consider how T in one M2XT2 layer is stacked with respect to T in a neighboring M2XT2 layer. There are two available options, illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1: (i) on-top (denoted by subscript AA) or (ii) close-packed (subscript AB). In addition, we have also accounted for different M2CT2 structures and stackings reported in the literature, such as a MXene originating from a MAX phase that will inherit the zig-zag stacking of the M2X layers. This requires unit cells comprised of even numbers of M2X layers (herein only 2 have been considered). For direct synthesis, there is no structural history to account for, and depending on the stacking of M2XT2 layers and termination site, we have considered structures with one (1) or three (3) M2X subunits along the c-axis. In order to distinguish the MXene structures from one another when combining different termination sites, stackings, and number of unit cells, we here introduce a notation that describes the number of M2XTx layers in the unit cell (1, 2, or 3), the termination site (FCC, HCP, FCC/HCP, or Top), and the stacking of M2XTx layers (subscript AB or AA). In total, 13 ml-MXene structures have been considered, and these are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1. Supplementary Table 1 provides complementary structural data such as space group and Wyckoff sites for each structure. Altogether, four lowest-energy structures (see Fig. 2b), could be identified, being in focus from this point forward.

a Termination sites for MXenes in four different configurations with metal atoms in blue, carbon in black, and termination species in orange. b Schematic illustration of low-energy structures for multilayer M2CT2.

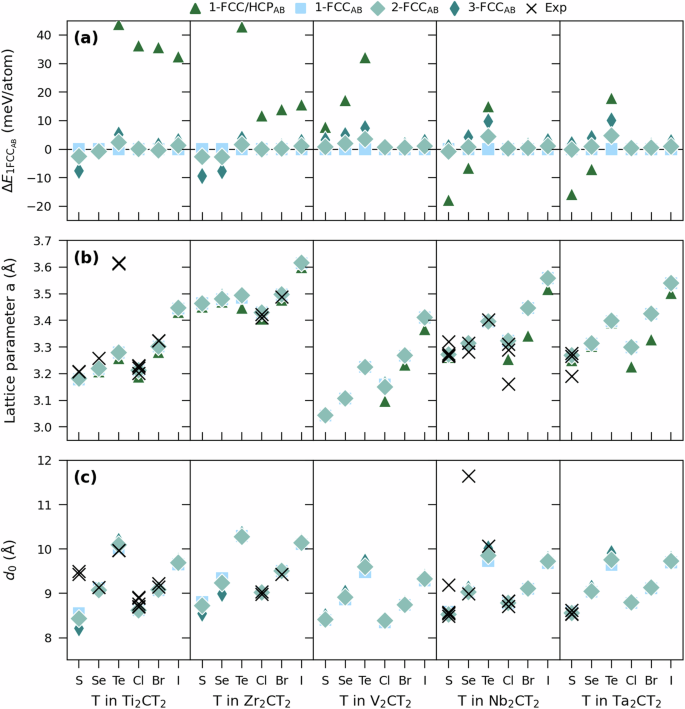

Figure 3a shows the energy difference of four selected low-energy structures with respect to 1-FCCAB for M2CT2 (see Supplementary Fig. 2 and 3 for energy differences of all structures). The exchange-correlation interactions were treated by van der Waals density functional (DFT-D3) developed by Grimme et al.32. FCCAB (1-FCCAB, 2-FCCAB, or 3-FCCAB) is found to be the lowest in energy for 26 of 30 systems, the exception being 1-FCC/HCPAB for Nb2CS2, Nb2CSe2, Ta2CS2, and Ta2SeC2. The three structures of lowest energy for each M2CT2 are summarized in Supplementary Table 2, along with their calculated total energy. Among these, we find a majority of the four selected low-energy structures in Figs. 2b and 3. The phonon dispersion for each of the considered M2CT2 compositions in its lowest energy structure can be found in Supplementary Figs. 11–15, showing that all are dynamically stable. Notable is that for Zr2CCl2, a larger supercell was required to eliminate the presence of imaginary frequencies along in-plane phonon modes.

a Relative energies for various stackings compared to 1-FCCAB. b In-plane lattice parameter a and c center-to-center spacing d0 for various low-energy stackings considered for multilayer M2CT2.

Qualitatively and quantitively similar results were also obtained when using the van der Waals density functional (rev-vdW-DF2) in the version developed by Hamada33,34 (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 6) which render validity for our use of the van der Waals density functional (DFT-D3) developed by Grimme et al.32. Also note that both dispersion corrections reveal that AB stackings are always favored over AA. In comparison, calculations without dispersion correction (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 7c), resulted in AB and AA stackings degenerate in energy. This is a clear indication that van der Waals interactions are present in multilayer M2CT2 and should not be neglected.

Calculated in-plane lattice parameter a is shown in Fig. 3b for M2CT2. For each M, a increases along the series S–Se–Te and Cl–Br–I. This follows the increased size of the termination species, see Supplementary Fig. 8. A comparison with experimentally reported values (13 M2CT2 MXenes, see Table 1) shows an overall good correspondence for 12 systems, the only exception being Ti2CTe210. Note that in ref. 10 it was suggested that Te is positioned on top of Ti, corresponding to the 1-TopAB or 3-TopAB structures in Supplementary Fig. 1. It was also suggested that this is distinctively different from the MXenes with smaller surface groups, which are positioned between hexagonally packed Ti surface atoms, corresponding to FCCAB structures in Fig. 2. However, Ti2CTe2 in 1-TopAB or 3-TopAB is found at +350 meV/atom higher in energy as compared to 1-FCCAB, and it is therefore not likely to find Te terminations on top of Ti. Moreover, comparing simulated XRD for relaxed structures 1-FCCAB and 1-TopAB of Ti2CTe2 (Supplementary Fig. 9) with measured diffractogram in ref. 10 (Supplementary Fig. 10) gives the best match for 1-FCCAB. Altogether, this suggests that 1-FCCAB is the likely structure of ml-Ti2CTe2.

Figure 3c shows center-to-center spacing d0 and represents the distance from one C-layer to the next C-layer. For 1-FCCAB, this corresponds to the out of-plane lattice parameter c, whereas for 2-FCCAB and 3-FCCAB, it represents c/2 and c/3, respectively. A striking correspondence is found for most systems when comparing calculated d0 values with reported values. However, for Ti2CS2, the calculated d0 is about 1 Å smaller than reported values. For Nb2CSe2, the two reported values differ significantly with d0 = 11.648 Å for top down synthesis of Nb2CSex (x ≈ 1) from Nb2AlC treated with molten salt10, compared to d0 = 8.997 Å for bottom-up synthesis of Nb2CSe2 from sintering35. The latter matches calculated values very well. The overall agreement of experimental data and calculated values for both lattice parameters and center-to-center spacings suggest that the relaxed structures from our DFT calculations are realistic and support the presence of interlayer van der Waals interactions. The structures as such can therefore be utilized for more in-depth calculations, see below.

Modeling single-sheet MXene with ideal termination coverage

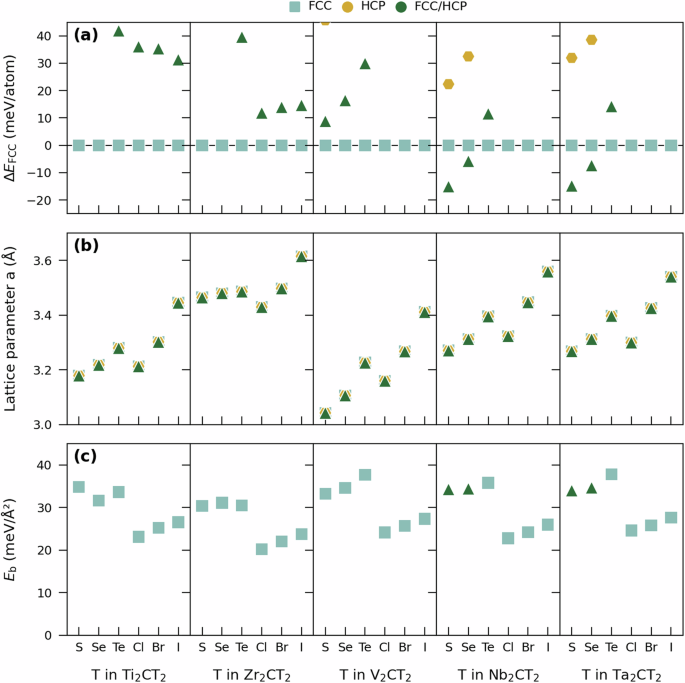

The number of configurations considered for ss-M2CT2 has been reduced to four since we no longer have to account for how different MXene sheets are stacked. The configurations FCC, HCP, FCC/HCP, and Top are schematically illustrated in Fig. 2a. Figure 4 shows the energy difference with respect to FCC, calculated in-plane lattice parameters a, and binding energy Eb. From en energy point of view, the results for ss-MXenes in Fig. 4a match those observed for ml-MXenes in Fig. 3a, as expected. The FCC configuration is found lowest in energy for 26 out of 30 ss-MXenes whereas the FCC/HCP configuration is favored for Nb2CS2, Nb2CSe2, Ta2CS2, and Ta2SeC2. Note that HCP and Top configurations are for all systems found at higher energy than FCC and FCC/HCP (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 21). The calculated in-plane lattice parameter a shown in Fig. 4b are similar to those obtained for ml-MXenes in Fig. 3b. Again, the observed trends correlate with the size of T (see Supplementary Fig. 8 for comparison), and a increases along the series S–Se–Te and Cl–Br–I.

a Relative energies for various configurations compared to FCC terminated ss-M2CT2 and b in-plane lattice parameter a. c Binding energy Eb for the ground-state configuration of ml-M2CT2.

Figure 4c shows the binding energy Eb for ml-MXenes, i.e., the energy required to break the multilayers into corresponding single sheets, as defined in Eq. 1, for the lowest energy of FCC, HCP, or FCC/HCP configurations. Note that the ml-MXene counterpart in Eq. (1), i.e., E3D, is represented by corresponding FCCAB or FCC/HCPAB structure of lowest energy in Fig. 3a. Eb spans from 20.2 meV/Å2 for Zr2CCl2 to 37.8 meV/Å2 for Ta2CTe2 and is comparable to Eb calculated for well-known van der Waals materials including graphite (~18–30 meV/Å2), hexagonal boron nitride (~13–25 meV/Å2), and transition-metal dichalcogenides (~20–35 meV/Å2)36,37. Within each set of M2CT2 sharing transition metal M but with different termination T, Eb is always lower for halogens (Cl, Br, I) than for chalcogens (S, Se, Te). There is also a slight increase in Eb along the series S–Se–Te and Cl–Br–I, which correlates with the increasing size of the chalcogens and halogens. The binding energies Eb for M2CT2 is correlated to the mechanical exfoliation potential, and may, at least in part, be correlated also to the exfoliation potential. Considering the harsh chemicals typically used for delamination of halogen-terminated MXenes, e.g., n-BuLi and NaH,10,12,23, identifying the MXenes of lowest binding energy may easier facilitate conversion of ml-MXene into ss-MXene.

Modeling multilayer MXene with non-ideal termination coverage

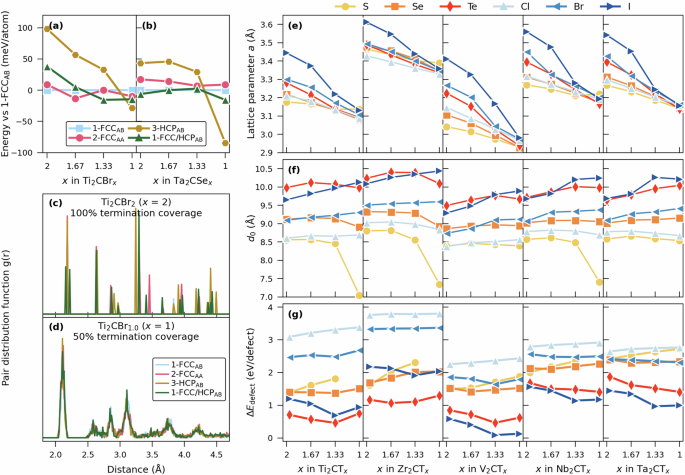

To model non-ideal termination coverage in M2CTx, x < 2, the special quasi-random structure (SQS) method38 was used to generate supercells composed of 120 or 180 atoms in total, depending on initial structure size, or with 48 and 72 T-sites, respectively. Based on Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 2, a few selected ml-MXene structures have been considered for a detailed investigation at non-ideal termination coverage. The relation between the conventional unit cells used for modeling ideal M2CT2 and the supercells used for non-ideal M2CTx is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 26. In addition to 100% termination coverage (ideal, x = 2.0), we have considered 83.3%, 66.7%, and 50% coverage, with T distributed in a disordered manner, corresponding to x = 1.667, 1.333, and 1.0, respectively. Figure 5a, b shows the energy difference with respect to 1-FCCAB for four selected structures (1-FCCAB, 2-FCCAA, 3-HCPAB, 1-FCC/HCPAB) of Ti2CBrx and Ta2CSex as a function of the termination coverage x. At x = 2, 1-FCCAB is lowest in energy for Ti2CBr2 and 1-FCC/HCPAB is lowest for Ta2CSe2 while 3-HCPAB is highest in energy for both MXenes. However, with decreasing termination coverage the energy difference between the considered structures is reduced and they become more alike. This is also valid for other T and structures (Supplementary Figs. 27 and 28). At x = 1, i.e., for a coverage of 50%, the energy difference is small, within ~30 meV/atom. The exception is the 3-HCP structure for Ta2CSex, explained below. The trend in energy is supported by Fig. 5cd where the pair distribution function at x = 2 (Fig. 5c) is compared to x = 1 (Fig. 5d) for Ti2CBrx. At x = 2, there is a distinct difference between considered structures, to be compared with x = 1, where all structures show the same distribution. The latter indicates that all the relaxed structures are similar. A comparison of the relaxed structures at x = 1, illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 30b, support this observation and shows that the termination is no longer only occupying the initially assigned site (FCC, HCP or FCC/HCP as seen in Supplementary Fig. 30a) but rather consists of a mixture of FCC and HCP. This means that at low enough coverage, in particular for x = 1, the initially assigned structure, whether being FCC, HCP or FCC/HCP, plays a minor role. Of more importance is the final relaxed structure and the degree of termination coverage. Based on this, detailed investigation of ml-M2CTx with non-ideal termination coverage will be focused on the 1-FCCAB structure.

Energy difference of various structures with respect to 1-FCCAB for a Ti2CBrx and b Ta2CSex as function of the termination coverage x. Pair distribution function for different structures of Ti2CBrx with c x = 2 and d x = 1. e Optimized in-plane lattice parameter a, f center-to-center spacing d0, and g defect formation energy (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) as a function of termination surface coverage x for M2CTx. Data retrieved for relaxed structures with initial 1-FCCAB stacking.

Figure 5e shows a steady decrease of lattice parameter a with decreasing termination coverage x. This becomes more pronounced with larger size of T. Of additional interest for ml-MXene is the evolution of the center-to-center distance d0 with decreasing x, shown in Fig. 5f. For Br- and I-based M2CTx, a clear increase in d0 is found with decreasing coverage, indicating a reduced interaction between the M2CTx sheets. For S- and Se-based M2CTx, we observe none to a small decrease in d0. Notable is that among S-based M2CTx, a distinct drop in d0 is observed at x = 1, as compared to x > 1, that can be correlated to a collapse of the double T-layers into one. This is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 31 for Ti2CSx. Such collapse can be observed for 1-FCCAB Ti2SC1.0, Zr2CS1.0 and Nb2CS1.0 in Fig. 5f and for 3-HCPAB Ta2CSe1.0 in Fig. 5b. The latter structure displays a significantly lower energy than 1-FCCAB, which indicates a more favored configuration due to the presence of a single T-layer. The consequences of such collapse will be discussed later in this work.

When decreasing the termination coverage, the unoccupied termination sites can be viewed as defects in the form of vacancies or vacant T sites. From this point of view, it is possible to estimate the vacancy/defect formation energy, (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}), as defined in Eq. (2). (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) gives information about the cost of creating T-vacancies when decreasing the coverage x. Figure 5f shows (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) for M2CTx (excluding structures with collapsed T-layers). (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) is largest for Zr2CClx, around +3.8 eV/defect, and from an energy point of view this MXene is the M2CTX with least tendency to deviate from being fully terminated (M2CT2). The MXene most prone for having a non-ideal termination overage is V2CIx with (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) close to zero for x ≤ 1.333. A clear trend is observed with decreasing (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) along the series S-Se-Te and Cl-Br-I, indicating higher tendency for more defects (empty termination sites). Another observation is that for T of large size, such as for Te and I, (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) decreases with decreasing x, i.e., the energy required for creating a defect is reduced for lower values of x. The opposite trend is observed for the smaller-sized S, Se, and Cl, where (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) increases with decreasing x. These trends can be correlated to the size of T and changes in center-to-center spacing d0 in Fig. 5.

Modeling single-sheet MXene with non-ideal termination coverage

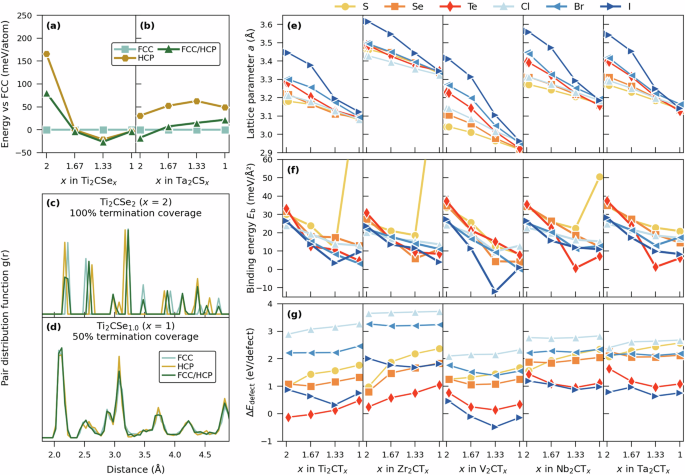

The SQS method38 was used to generate ss-M2CTx 6×6 supercells composed of 180 (x = 2) to 144 (x = 1) atoms for FCC, HCP, and FCC/HCP configurations. We have considered 100%, 83.3%, 66.7%, and 50% coverage, with T distributed in a disordered manner, corresponding to x = 2, 1.667, 1.333, and 1, respectively. Figure 6a, b shows the energy difference of the three configurations with respect to FCC for Ti2CSex and Ta2CSx as a function of the termination coverage x. Similar to ml-MXenes in Fig. 5a, b, the different configurations converge towards similar energies for a reduced termination coverage x, see for example, Ti2CSex at x = 1. Again, this is confirmed by Fig. 6c, d for Ti2CSex, where the pair distribution function at x = 2 (Fig. 6c) gives rise to different peaks for the three configurations, while for x = 1 (Fig. 6d) they overlap with each other. Supplementary Fig. 32 schematically demonstrates this evolution for Ti2CSex, from distinctly different FCC, HCP and FCC/HCP configurations at x = 2 to mixed terminations of FCC and HCP at x = 1, irrespective of the initially assigned site (FCC, HCP or FCC/HCP). Based on this, detailed investigation of ss-MXenes with non-ideal termination coverage is focused on results obtained using the FCC configuration.

Energy difference with respect to FCCAB for selected structures of a Ti2CSex and b Ta2CSx as function of the termination coverage x. Pair distribution function for different structures of Ti2CSex with c x = 2 and d x = 1. e In-plane lattice parameter a, f binding energy Eb for 1−FCCAB configuration of ml-M2CTx, g defect formation energy (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) as a function of termination surface coverage for ss-M2CTx. Data retrieved from relaxed ss-M2CTx structures with initial FCC configuration.

Since the ml-MXenes studied herein display weak van der Waals interaction between the M2CTx sheets, similar trends are observed for ss-M2CTx. A decrease in the in-plane lattice parameter a with decreasing surface coverage x, shown in Fig. 6e, is found for all ss-M2CTx. The decrease in a is also more pronounced for larger size of T In comparison, a larger T (such as I and Te) for ideal coverage has a larger impact on the M2C layer as compared to a small T (such as S and Cl), while for a reduced surface coverage, the impact from a larger T becomes less pronounced.

Figure 6f shows the binding energy Eb for ml-MXenes, composed of layers of ss-M2CTx, as function of termination coverage x, as defined in Eq. (1). Note that the ml-M2CTx counterpart in Eq. (1), i.e., E3D, is represented by corresponding 1-FCCAB, structure in Fig. 5. A decrease in Eb is observed for all ss-M2CTx with decreasing coverage x, which is an indication of a reduced interlayer interaction. At x = 1, Eb is around 10 meV/Å2 which is about 100–300% lower than for x = 2. This implies that deviating from fully terminated ml-MXenes (x = 2), and instead aiming for ml-M2CTx with x < 2, may facilitate easier conversion of ml-MXene into ss-MXene. The dilemma we are facing is that the binding energy, which is an indicator for potential of conversion from ml– to ss-MXene, can be made weaker with decreasing termination coverage. However, too small termination coverage may lead to collapsed T-layers (see x = 1 in Supplementary Fig. 31) that, in turn, leads to a substantial increase in Eb. This can be seen for Ti2CS1.0, Zr2CS1.0, and Nb2CS1.0 in Fig. 6f.

The defect formation energy, (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) as defined in Eq. (2), for ss-M2CTx in Fig. 6g display qualitatively and quantitatively similar trends as shown for ml-M2CTx in Fig. 5g. Within each set of ss-M2CTx sharing transition metal M, but with different termination T, (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) is always the largest for T = Cl whereas the lowest values are observed for T = Te when M = Ti and Zr, and for T = I when M = V, Nb, and Ta. The overall trend is that (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) decreases along the series S–Se–Te and Cl–Br–I.

Electronic properties of multilayer and single-sheet MXenes

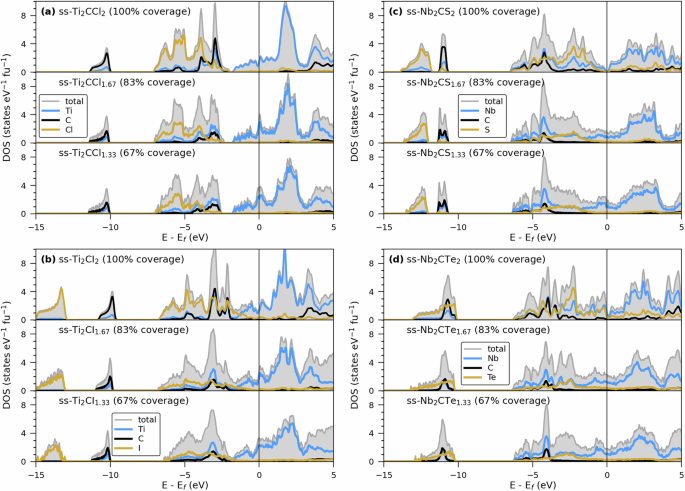

The weak van der Waals interaction between M2CTx sheets in ml-MXenes is also reflected in its electronic properties. This is demonstrated in Supplementary Figs. 33–36 where a comparison of the density of states (DOS) for ml– and ss-M2CTx for eight systems, Ti2CTx and Nb2CTx with T = S, Te, Cl, I, for full and 67% termination coverage is shown. The chosen terminations encompass light and small elements (S and Cl) as well as those of larger size and atomic number (Te and I). The DOS represents the lowest energy structure for each composition, as given in Figs. 3 and 4 for full termination coverage and 1-FCCAB (ml-MXene) or FCC (ss-MXene) for 67% termination coverage.). The DOS for a ml– and ss-MXene of the same composition, at 100% and 67% termination coverage, is more or less identical. This is observed both for small and light terminations (S or Cl) and for large and heavy termination species (Te and I), and further supports the presence of weak van der Waals interaction between singles sheets of M2CTx in ml-M2CTx. Additional DOS for ideal ml-MXenes in their lowest energy structure can be found in Supplementary Figs. 16–20. Based on observations in Supplementary Figs. 33–36, it is expected that the DOS for corresponding ss-MXenes should be quite similar for all herein investigated MXenes.

Of additional interest for this work is the change in the electronic properties when deviating from ideal coverage (100%) to non-ideal termination coverage (83 and 67%). Figure 7 shows DOS for four ss-MXene systems, Ti2CTx (T = Cl and I) and Nb2CTx (T = S and Te), where a clear increase in the states at and close to the Fermi level is found for x < 2 as compared to x = 2 (full coverage). It has previously been shown (for Ti-based MXene) that the degree of surface terminations can strongly influence the number of states at the Fermi level and thereby the MXenes’ electronic conductivity14. This implies that non-ideal termination coverage in chalcogen and halogen MXenes gives rise to an increased number of non-bonding metal states at the Fermi level due to a decrease in the number of M–T bonds. This, in turn, may give rise to an increased electrical conduction.

DOS for a Ti2CClx, b Ti2CIx, c Nb2CSx, and d Nb2CTex. Top panels represent full coverage (x = 2) while mid and bottom panels shows DOS for 83% (x = 1.667) and 67% (x = 1.333) surface termination coverage, respectively.

Oxygen incorporation in vacant termination sites

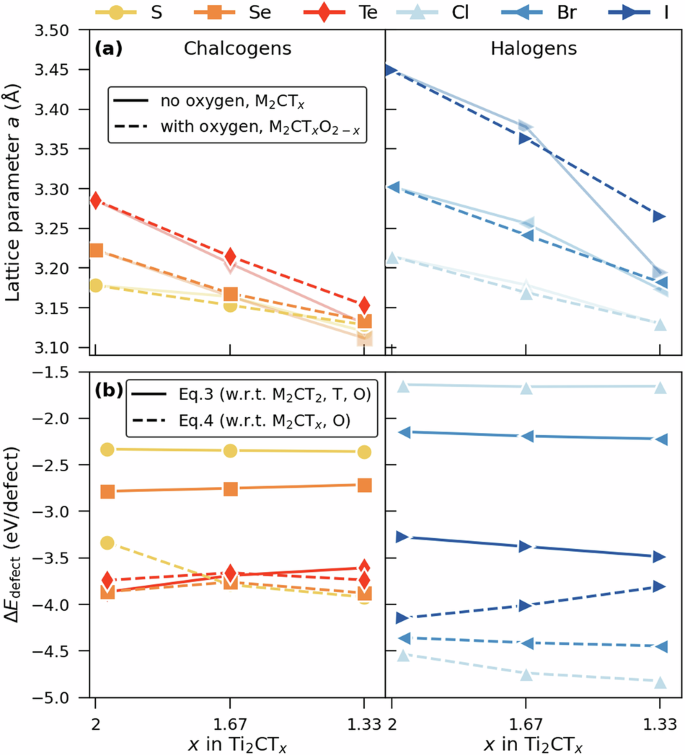

MXenes synthesized through a top-down or bottom-up approach may lead to a surface termination coverage diverging from the ideal case (x = 2). This is exemplified in Table 1 with multiple M2CTx reported with x < 2, and also indicated by the rather small defect formation energies shown in Figs. 5g and 6g for larger-sized termination species. The deviation from ideal surface termination coverage may lead to highly active vacant sites that may be populated by oxygen, depending on the synthesis conditions used or ambient conditions. This motivates initial theoretical evaluation of such scenario. Here we have focused on ss-Ti2CTxO2-x, motivated by the many Ti-based MXenes listed in Table 1. Note that for ss-Ti2CTxO2-x, the surface termination coverage is ideal, i.e., with oxygen populating all vacant termination sites, and being composed of a random mixture of T and oxygen.

Figure 8a shows the in-plane lattice parameter, a, for ss-Ti2CTxO2-x. For comparison, oxygen-free ss-Ti2CTx have been included as well. Both Ti2CTxO2−x and Ti2CTx show a decrease in a with increased oxygen concentration, becoming more pronounced with a larger T as indicated by a larger slope. The difference in a when comparing Ti2CTxO2−x and Ti2CTx, is, in general, small and can be related to the rather small size of oxygen (see Supplementary Fig. 8). Thus, having vacant T-sites or oxygen populating the same sites gives a similar impact from a structural perspective. Also noteworthy is that having the surface completely covered with a mixture of terminations T and oxygen does not give rise to a mixture of FCC and HCP site occupation as was observed in Fig. 6a–d. Instead, we observe that the initially assigned FCC site is maintained after relaxation. This effect is most pronounced for T = I at x = 1.33 with a decreasing more for the oxygen-free case due to a high-degree of FCC and HCP mixed sites as compared to the Ti2CI1.67O0.33 with only FCC sites for I and O.

a Lattice parameter a as function of surface termination coverage x for Ti2CTx and Ti2CTxO2−x. b Defect formation energy, (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}) calculated using Eqs. (3) and (4), as function of surface termination coverage x for Ti2CTxO2−x.

The cost (or gain) in energy from populating the vacant T sites with oxygen has been quantified through evaluation of the defect formation energy upon oxygen incorporation at vacant T sites for M2CTx. This has been calculated in two ways. Equation 3 where the ideal M2CT2 is used as reference and Eq. (4) where the reference is M2CTx. Furter details are given in Methods.

As a starting point, Fig. 8b shows negative values for (triangle {E}_{{rm{defect}}}), indicating that it is energetically favorable to replace terminations T with oxygen for Ti2CT2 (Eq. (3))as well as to add oxygen to Ti2CTx. Furthermore, the result from using Eq. (3) shows that it becomes energetically more favorable to replace T with oxygen along the series S–Se–Te and Cl–Br–I. Part of this may explained by the replacement of a larger-sized T with a smaller-sized oxygen, reducing the crowding among the surface terminations. This effect is less pronounced when oxygen is mixed with smaller-sized S and Cl. Using Eq. (4) instead, we compare Ti2CClxO2−x with Ti2CTx. Noteworthy are the opposite trends observed for halogen-terminated MXenes, where a comparison with respect to Ti2CT2 (Eq. (3)) is least favorable for Ti2CClxO2−x and most favorable for Ti2CIxO2−x whereas comparison with respect to Ti2CTx (Eq.(4)) is least favorable for Ti2CIxO2-x and most favorable for Ti2CClxO2−x. These trends can be related to the defect formation energies shown in Fig. 6g for Ti2CTx but also to the mixed terminations in Ti2CTx (Fig. 6a–d) when x < 2. Moreover, the difference between Eqs. (3) and (4) results in Eq. (2). As a consequence, the large difference observed for Ti2CClxO2−x when comparing usage of Eqs. (3)and (4) can be explained by the small-sized Cl that easily give rise to mixed terminations sites, as is demonstrated in Fig. 6b.

Mechanical properties for single-sheet MXene with ideal termination coverage

The sheet strength of ss-MXenes is important for determining their potential performance and reliability in practical applications. A large sheet strength can indicate that the MXene can withstand bending, stretching, and other mechanical deformations without losing its functionality. Here we choose to focus on the Young’s (E), shear (G), and bulk (B) modulus for ideal ss-M2CT2. Young’s modulus measures the stiffness of a material. A high Young’s modulus suggests that the material can sustain significant tensile loads without significant deformation, contributing to its overall strength. Shear modulus measures the material’s response to shear stress. Bulk modulus measures the material’s resistance to uniform compression. While bulk modulus is more relevant for 3D materials, it still provides insights into the compressibility of the material. For ss-MXenes, bulk modulus can indicate the behavior under isotropic stress conditions, which might be relevant in multilayer stacks. The combined effect of these moduli gives a comprehensive picture of the mechanical properties of ss-MXenes. A material with high values of Young’s modulus, shear modulus, and bulk modulus will generally have high sheet strength, meaning it can withstand various types of stress and maintain its structural integrity.

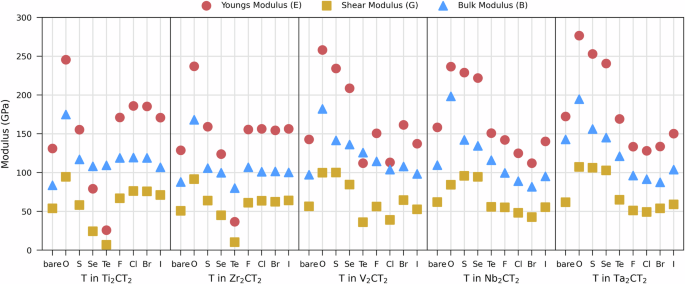

Figure 9 illustrate the trends and variations in mechanical properties based on the termination T and metal M for ss-M2CT2. Chalcogen terminations (O, S, Se, Te) are shown to generally decrease the modulus values from O to Te, with oxygen consistently providing the highest moduli. Halogen terminations (F, Cl, Br, I) similarly exhibit decreasing or constant trends from F to I, with fluorine showing high modulus values, close to oxygen. Among the metals, Ti and Ta compounds tend to exhibit higher modulus values across all terminations, indicating strong bonding and stiffness, while Zr and V compounds show relatively lower values. Note that bare ss-MXenes, while hypothetical, in general leads to low modulus comparable to those found for halogen terminations. More specifically, Young’s modulus spans from 26 GPa for Ti2CTe2 to 277 GPa for Ta2CO2, shear modulus from 7 GPa for Ti2CTe2 to 107 GPa for Ta2CO2, and bulk modulus from 80 GPa for Zr2CTe2 to 198 GPa for Nb2CO2. This can be compared with Young’s modulus for graphene (800–1000 GPa), transition metal chalcogenides (150–300 GPa), and hexagonal boron nitride (250–280 GPa)39. MXenes are hence significantly softer than graphene and have a stiffness almost comparable to transition metal chalcogenides and hexagonal boron nitride. It should be noted, however, that mechanical properties of 2D materials largely depend on the density of crystal defects, and are thus related to the preparation methods used39,40,41. Hence, future work on mechanical properties of MXenes should account for non-ideal composition, including, but not limited to, the surface termination coverage.

Calculated Young’s, shear, and bulk modulus for different terminations T and bare MXene across various metals M in ss-M2CT2.

MXenes are a class of versatile two-dimensional materials with a diverse range of compositions and properties, which hold promises for a wide range of potential applications. Their synthesis, whether through top-down or bottom-up approaches, significantly impacts their structure, morphology, and surface termination, which in turn affect their physical and chemical properties. Precise control over MXene composition and surface termination is crucial for tailoring their properties for specific use.

In summary, by employing DFT calculations, we systematically investigated the deviation from ideal surface termination coverage, focusing on both multilayer and single-sheet M2CTx MXenes with terminations from Groups 16 and 17 elements. The results demonstrate that non-ideal termination coverage leads to a mixture of termination sites and significant changes in stability and in structural and electronic properties. Key findings include that non-ideal termination coverage can lower the binding energy, which may facilitate easier conversion from multilayer to single-sheet MXenes. However, too low termination coverage may result in structural collapse leading to strong interlayer bonding that may hinder delamination. Additionally, trends of defect formation energy indicate that MXenes with a larger-sized termination are more prone to having non-ideal coverage, which impacts their electronic properties by increasing states at the Fermi level, potentially enhancing the conductivity. Moreover, the incorporation of oxygen into vacant termination sites was also found to be energetically favorable, providing further avenues to tailor MXene properties. We also show that for ideal termination coverage, x = 2, there is a significant variation in the Young’s, shear, and bulk moduli, that highlights the significant impact of the termination T and the metal M on the overall mechanical behavior of MXene.

The predicted properties of MXenes, particularly those related to non-ideal termination coverage and its impact on structural, electronic, and mechanical properties, could have several important implications for their possible applications. Having non-ideal termination coverage, leading to mixed termination sites, could create more active sites on the MXene surface, potentially enhancing their catalytic activity. This could be particularly beneficial for applications such as hydrogen evolution reactions (HER) or oxygen reduction reactions (ORR) where accessible active sites are critical. Moreover, incorporation of oxygen into vacant sites could be used to tailor the surface chemistry for chemical capture and conversion processes, potentially improving reaction rates and selectivity. For the same areas, an enhanced electrical conductivity for non-ideal termination coverage is also of interest for improving the MXene performance. Further, precise control over surface termination may allow for the design of MXenes with customized mechanical properties for use in flexible electronics or other applications where both mechanical resilience and tunable conductivity are required. Altogether, the results presented herein underline the importance of precise control over MXene synthesis and surface chemistry, suggesting that advancements in these areas will significantly expand the practical use of MXenes in various applications.

Methods

Computational details

All calculations were performed within the framework of density functional theory (DFT) as implemented in Vienna ab-initio software package (VASP) version 5.4.442,43,44 with the projector augmented wave (PAW) method45,46,47 and the planewave basis set expended to a kinetic energy cutoff of 520 eV. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional47 was used to describe the electron exchange-correlation effects. PBE potentials used are listed in Supplementary Table 1. We used a k-point sampling, with a density of 0.1 Å-148. Structures were fully relaxed in terms of volume, shape, and atomic positions. The convergence criterion for self-consistency of relaxed structures is an energy convergence of 10−7 eV/atom and force convergence of 0.01 eV Å–1. Since multilayer MXenes terminated with halogens and chalcogens may possess weak interlayer dispersion forces, or van der Waals interactions, these have been described using the DFT-D3 method of Grimme et al.32. For selected ml-MXenes, we used the functional developed by Hamada (rev-vdW-DF2)33,34 which offers a more rigorous, non-empirical approach to modeling van der Waals interactions but at a higher computational cost. In comparison, calculations without dispersion corrections were considered to assess the importance of dispersion forces for ml-MXenes. For calculations of delaminated single-sheet MXenes, the periodic image interactions were avoided by employing a vacuum layer of about 25 Å.

The binding energy Eb represents the energy difference when going from ml-MXene (3D) to ss-MXene (2D) and is defined as

where E2D and E3D refer to the calculated total energy of relaxed ss– and ml-MXenes per M2CTx formula unit, respectively, and A is the surface area of the corresponding ml-MXene. Note that the surface area A of ml– and ss-MXene are approximately the same.

To model non-ideal termination coverage in M2CTx, x < 2, the special quasi-random structure (SQS) method38 was used to generate supercells with T distributed in a disordered manner at various coverages. With the SQS method, correlation functions of a finite unit cell are compared to those of an infinite ideally random system, and SQS generated structures are considered to give a good approximation of a close to random arrangement

The defect formation energy (where the defect in this case is a vacant termination site) for M2CTx is calculated using

where ({E}_{{rm{supercell}}}left({{rm{M}}}_{2}{rm{C}}{{rm{T}}}_{x}right)) and ({E}_{{rm{supercell}}}left({{rm{M}}}_{2}{rm{C}}{{rm{T}}}_{2}right)) are the total energies of the supercell with non-ideal (x < 2) and ideal (x = 2) termination coverage, respectively, and the last term corresponds to the number of ({N}_{i}) termination species removed from the ideal supercell and ({mu }_{i}) is the chemical potential of species i. Here µi is represented by the calculated energy of termination i in their ground-state crystal structure.

In the case of oxygen occupying vacant termination sites, the defect formation energy has been calculated in two ways:

and

where ({E}_{{rm{supercell}}}left({{rm{M}}}_{2}{rm{C}}{{rm{T}}}_{x}{{rm{O}}}_{2-x}right)), ({E}_{{rm{supercell}}}left({{rm{M}}}_{2}{rm{C}}{{rm{T}}}_{2}right)), and ({E}_{{rm{supercell}}}left({{rm{M}}}_{2}{rm{C}}{{rm{T}}}_{x}right)) are the total energies of the supercells with and without oxygen at ideal (x = 2) and non-ideal (x < 2) termination coverages, respectively, ({mu }_{{rm{T}}}) and ({mu }_{{rm{O}}}) are the chemical potential of T and oxygen, and ({N}_{i}) represent the number of termination species removed (for T) and added (for O) in the M2CTxO2−x supercell.

Responses