Polybutadiene structural effects on dynamic wetting

Introduction

Ammonium perchlorate (AP) composite propellants are commonly used in both missile propulsion and launch systems due to their performance and storability1. Propellants contain as much as 88 wt% AP, polymeric binder (e.g., hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene or HTPB), and metal additives (e.g., Al) with other minor ingredients. The propellant formulation dictates the linear burning rate of the propellant and may be tailored during manufacturing by adjusting AP particle sizes. This burning rate and the exposed burning surface area of the propellant grain are primarily responsible for dictating the mass flow rate for a specific thrust profile. Simple grain geometries can be fabricated with traditional cast-cure approaches; however, more intricate designs required for high-thrust applications and in general to expand the mission design space are either impossible or cost-prohibitive using cast-cure approaches. As such, additive manufacturing (AM) techniques have been explored for solid rocket propellant applications2,3,4.

Previous AM techniques for propellants have typically focused on extrusion-based approaches. The disadvantages to these approaches are (a) that a filament must be manufactured with a specific formulation (e.g., AP sizes, weight fraction, etc.), which limits tailorability, (b) the extremely high viscosity due to the high solids loading that presents a technological challenge, and (c) the filament being printed is rated as an explosive itself. Powder bed, binder jetting (PBBJ) is another AM approach that has received attention with metal and ceramic composites5,6, but very limited attention for propellants. This technique initially deposits powder (e.g., AP) followed by the deposition of binder (or binder solution). In terms of solid propellant, PBBJ will enable spatial variation of AP particle size and binder composition (including minor additives) to further increase the design space. One challenge in developing this technology is the lack of understanding of how binders (and solutions containing binders) of interest (i.e., HTPB) will wet the powder, which in application will be a porous bed. This problem is inherently complex with binder able to spread along the surface, and penetrate the powder bed while potentially disrupting the powder. Simpler experiments are necessary to investigate each fundamental aspect of this more complex process.

Recent work7 quantified the static wetting of AP by commercially available HTPB variants. Improved static wetting is believed to assist in improving the mechanical properties of the final propellant. The deposition process for PBBJ is dynamic and thus, the hydrodynamics of how a deposited droplet reaches its equilibrium diameter must be understood. The extent of spreading in this context will be related to the spatial resolution in directions parallel to the surface (penetration dynamics into the powder bed are important for the vertical resolution for PBBJ manufactured propellants. Using already commercially available materials is beneficial for cost and allows direct comparison to current propellant formulations. From a scientific perspective, variations of HTPB prepolymers are available and these differences will affect rheological properties and have been shown to change wetting behavior7. Therefore, the effect that polymer structure has on the dynamic wetting process needs to be investigated. Aside from the practical aspects mentioned, investigating the different polymer structures will be able to inform the future development of polymer binders for desired wetting in binder jetting processes. We focus on an important subclass of binder solutions, those with low molecular weight binders at high concentrations, which enable the printing of viscous reactive pre-polymers that later undergo a curing process. These low molecular weight components enable lower viscosities and thus rapid jetting during printing, but their spreading dynamics are poorly understood even on solid surfaces, especially at high concentrations. Thus, our work provides an important advance in fundamental knowledge.

Dynamic wetting by droplets impacting surfaces has been extensively studied for inkjet printing, agriculture8, deicing, and forensic science9, among other applications. These experiments capture the physics of the binder deposition process and enable control over the hydrodynamics through changes to the droplet impact velocity/initial droplet height. The droplet mass, diameter, and velocity just prior to impact dictate the total energy of the system between kinetic and surface energy. The droplet starts to spread immediately after impact where the kinetic energy is transformed into a combination of surface energy (i.e., surface area increase) and viscous dissipation. This energy balance at the maximum spreading diameter is shown in Eq. (1) when all kinetic energy is consumed by viscous dissipation or transformed into surface energy,

where d is the diameter, U is the velocity, ρ is the droplet density, γ is the surface energy, ϕ is the energy dissipated through viscous effects, and C is a constant that accounts for the shape of the final droplet. The 0 and max subscripts indicate impact and final, respectively.

Materials with a non-negligible elastic component may store energy elastically, which is typically released later as the material relaxes. A maximum spreading diameter, dmax, often normalized by the initial diameter, d0, and reported as the non-dimensional spreading ratio (Smax = dmax/d0), is reached when the kinetic energy is zero. Capillary effects often cause the droplet to retract after the maximum value is reached. The droplet may retract with enough kinetic energy to rebound or repeat the spreading/retraction phase, oscillating around the equilibrium diameter/contact angle10. Polymers added to droplet solutions have been shown to prevent or reduce rebounding although at relatively low concentrations (i.e., less than 5 g/L) depending on the polymer size and structure8,11,12. For the propellant application, concentrations on the order of 10 wt% are anticipated and different polymers (e.g., polybutadienes commonly used in propellants) are expected to be used. Data for this combination of conditions are absent from the literature. The energy conservation approach has been used to develop correlations between the maximum spreading ratio and relevant non-dimensional quantities (e.g., Re and We). The magnitude of Re and We indicate different regimes that control the dynamic wetting process.

The maximum spreading ratio depends on the competition of forces described by We and Re (i.e., capillary vs inertial vs viscous). Low impact velocities lead to capillary forces dominating the spreading where the maximum spreading ratio scales with We0.5. As the impact velocity increases, the maximum spreading scales with Re0.2 where viscous effects become more important13. Others have developed more universal correlations that bridge the gap between capillary and viscous regimes including with rough surfaces14. Many studies have focused on Newtonian systems, but recent work15 has extended this universal model to include non-Newtonian fluids, Eq. (2), where the non-Newtonian Reynolds number is used.

where the max subscript refers to the maximum value and the 0 subscript refers to the final droplet size. Non-Newtonian fluids are inherently more complex, but in some instances9, shear-thinning droplets spread similarly to Newtonian systems due to very high shear rates where the infinite shear viscosity is reached.

Temporal dependence of the spreading process also provides insight into the dominant forces. Inertia dominates the spread immediately following impact and the spreading ratio scales as t0.5 16 although the exponent will decrease depending on the difference between the advancing and static equilibrium contact angles17. Tanner’s work18 indicated that for smaller Re flows and later in the spreading event the spreading scales as t0.1 and is dominated by viscous effects for Newtonian systems. Non-Newtonian systems, specifically power-law fluids, display a different temporal dependence that depends on the power-law exponent, n. Power law fluid droplet spreading ratios scale as:

where the exponent has also been shown as n/(3n + 5)19,20. Newtonian fluids have a value of n of 1, which results in a spreading exponent consistent with Tanner. Theoretical and experimental studies for shear-thinning droplets indicate that these droplets will spread slower than Newtonian droplets that have the same zero-shear viscosity. Shear thickening systems will spread at a faster rate21.

The extent of spreading (i.e., Smax) will dictate the spatial resolution (along the powder bed surface) for the manufacturing application and will depend on the polymer structure, weight fraction in the droplet, and impact velocity. The influence of these parameters on the final droplet size must be determined. In addition, the dynamics of spreading for HTPB variants, especially at greater weight fractions (>1 wt%), are not commonly reported. Commonly used HTPB variants are relatively low molecular weight materials (i.e., on the order of 1000 g/mol). The combination of low molecular weight and high concentrations is unique and not well-studied in terms of the deposition processes. This study uses HTPB due to its application importance but the physics involved extend to other low molecular weight, high concentration polymer systems. We focus on an important subclass of binder solutions, those with low molecular weight that are absent from the more general droplet impact literature. Further, droplet spreading dynamics are studied on a compact, not loose, powder bed to isolate the influence of binder structure from the additional complexities of wetting in the application.

Methods

This work investigates both the influence of polymer structure, as well as the consequence of imparted shear rates on the oxidizer wetting process. Analysis of the effect of polymer structure and mass loading on AP-HTPB wetting necessitated a test setup and methodology that would allow for the isolation of the two variables while observing the wetting process in real-time. Droplet impact testing with HTPB-n-dodecane solution allowed for variation in droplet impact velocity and estimated droplet shear rates by adjusting of initial starting height of the released droplets. n-Dodecane was utilized as a solvent to lower droplet viscosity as impact velocities available in the laboratory were insufficient to achieve measurable spreading in the pure viscoelastic HTPB pre-polymer. Toluene was initially used, however; n-dodecane was chosen due to its ability to dissolve the polymer and low vapor pressure in contrast to toluene’s higher vapor pressure. Since the goal of this work is to determine the role of commercial polymer structure and concentration on the spreading, the low vapor solvent reduced complexity as initial droplet energy would also be used in the evaporation process. The choice of n-dodecane simplifies the physics even though toluene may be a better choice in the application of PBBJ.

Droplet impact setup

The in-house built droplet impact testing setup seen in Fig. 1 generated droplet impact and spreading events for analysis. HTPB droplet solutions were loaded into a 3 mL stainless steel syringe (SYR-SS3, New Era Instruments). The syringe was cleaned with toluene and acetone prior to adding the solution. Droplets (1.67 ± 0.01 mm) were dispensed with a 32-gauge disposable syringe tip (SANANTS PN: 30-07-3225). The 1.67 mm droplet provided a Bond number of approximately 0.2. A Bond number less than unity indicated that capillary forces were greater than gravitational forces in the droplet. Droplets impacted the surfaces from heights of 50 mm, 266 mm, and 425 mm. These impact heights resulted in impact velocities of 0.90 ± 0.02 m/s, 2.11 ± 0.02 m/s, and 2.58 ± 0.03 m/s, respectively. After the release of the droplet from the syringe tip, droplets free-fell through a laser gate monitored by a computer-based oscilloscope (Picoscope 5442D 60 MHz, max sampling rate 1 GS/s). The Picoscope provided a signal to trigger the high-speed camera (Photron Mini AX100 540K) that started the recording process. The high-speed camera had a mounted close-focus objective lens (Infinity K2 with CF-2 or CF-3 objective) and was backlit with a white LED light (GLL 550 48-SMD LED Panel). The image frame rate was set to 4000 frames/s. Image files were then saved and exported to be processed via Matlab script.

Schematic of the droplet impact experiment used for the study (left) and representative sequence of droplet spreading (right).

A series of custom-created Matlab functions processed the image data gathered during droplet freefall and spreading. Complete details of the processing are described by Raissi22 but are briefly described here for completeness. Functions for cropping, thresholding, edge detection, droplet characteristic calculations (e.g., diameter), and plotting were for analysis. Each successive droplet image was analyzed for instantaneous contact line width and instantaneous height. A representative image sequence is shown in Fig. 1. Based on spreading data, 3-point forward, 3-point backward, and 2-point central difference methods were utilized to calculate contact line velocities. Using contact line expansion velocities and instantaneous height, order of magnitude estimations for shear rates are obtained via Eq. (4)23 where U is droplet contact line spreading velocity and h is the instantaneous droplet height. Order of magnitude estimates for shear rates varied with contact line spreading velocity. Chandra23 assumed that spreading velocity immediately after impact was equivalent to impact velocity. Higher initial impact heights led to higher impact velocities for droplets. It should be noted that this order of magnitude value was used as a semi-quantitative comparison tool but the shear rates near the contact line are likely much higher21. Values for contact line spreading ratio were plotted as a function of the dimensionless time scale ({t}*) via Eq. (5) where t is time.

Materials

The study used mixtures of seven pre-polymers diluted with n-dodecane (Alfa Aesar, 99%). Polymer concentrations of 1.85 wt%, 3.85 wt%, 10 wt%, and 30 wt%, impacted compacted AP power pellets (200 μm nominal, AMPAC and Firefox). Pure polymer droplets had minimal deformation during initial impact tests and would not be useful for this application. Therefore, pure polymer droplets were not tested. The polymer concentration was limited by the solubility in n-dodecane. Seven variants of HTPB (CRS Chemicals Lot PP19042401, Cray Valley, Lots PP18122602, KK16033003, KK15072705, KK17062003, KK17092712, CV18083002, CV18110701) were tested and a summary of properties is shown in Table 1. Values for pure HTPB density and surface tension with the exception of surface tension for LBH-P 2000, LBH-P 3000, and HLBH-P2000 were provided by Cray Valley Chemicals. Surface tension values for LBH-P 2000 and LBH-P 3000 were measured in previous work7. A surface tension value for HLBH-P-2000 was not readily available either from Cray Valley Chemicals or the work Ramirez7 performed. Similarities in surface tension values for H-LBHP 2000 and H-LBHP 3000 were not anticipated given the difference in formulations. All polymers except for HTLO are linear chains. The number in the title indicates the nominal average polymer molecular weight. The HLBH variants have a hydrogenated carbon backbone. The -P polymers have primary OH groups.

The 7 pre-polymers utilized in the study were diluted by mass to 1.85 wt%, 3.85 wt%, 10 wt%, and 30 wt% HTPB in n-dodecane. Droplets consisting of 30 wt% HTPB were the primary focus of the study given the high pre-polymer content is expected in real-world manufacturing environments. The solubility of the HTPB pre-polymer in n-dodecane was determined by ASTM Standard D 3132-84 for each solution. Pre-polymer and n-dodecane solutions were mechanically mixed and allowed to reach equilibrium over a period of 24 h. Solutions were then optically inspected using LED backlighting to check for variations in light refraction in the solution. Homogeneous light refraction was used to indicate successful mixing. Solubility limits for HTPB pre-polymers in n-dodecane were found to be between 30 wt% and 40 wt% dependent on the HTPB polymer utilized. Additional details are presented in Raissi22. The effect of variations of temperature and humidity in the lab environment on solubility is expected to be minimal given the laboratory temperature was on average 21.6 °C and humidity 65.0% ± 5%. Values for solution density and surface tension were calculated by component mass fraction from industry-provided data for n-dodecane and HTPB24.

As part of a rheological study (TA Discovery Series HR-2 Hybrid Rheometer, 25 °C), the polymer solutions were exposed to shear rates varying from 1 s−1 to 1000 s−1 with subsequent fluid viscosity values recorded. Values for infinite shear viscosity and power law fluid exponent, n, were derived from the shear rate-viscosity curves using a Carreau–Yasuda equation. Despite the higher concentration of polymer, the elastic moduli are still very low, close to the detection limits of the instrument, at the conditions tested, and thus are not reported. This result does not imply the lack of elasticity at shear rates greater than what was tested, which may be present during droplet spreading particularly near the interface. The density (788.3 ± 1.6 kg/m3) and surface tension (25.0 ± 0.4 mN/m) variation between each 30% HTPB solution was minimal. Viscous properties were dependent on the type and amount of prepolymer. Additional measurements for the zero-shear viscosity were obtained using a rheometer (TA Instruments DHR-3) with a double-gap cylinder geometry to compare concentration effects for the LBH-3000 and HTLO variants (i.e., one linear, one branched polymer). The measurements were taken at 25 °C using a shear rate sweep spanning at least two decades between 0.1 s−1 and 1000 s−1 depending on the solution viscosity for best resolution. The zero-shear viscosity values were found by averaging the plateau region as the shear rate approached zero.

Droplets impacted compressed AP powder pellets. The AP pellets were compressed using a 25 mm diameter stainless steel die (Precision Elements 25 mm Pellet Press Die Set) at 181 MPa of pressure for 5 min. Calculations for a representative sample of AP pellets yielded a value of 95.50% ± 2.50%. To limit the adsorption of moisture from ambient air, the pellets were stored in a 40 °C vacuum drying box (Model DZF- 6020 D201 901666) until use. Surface roughness values for the AP pellets were taken with a portable surface roughness tester (Mitutoyo SJ-210). The average profile roughness for the evaluated length was 0.81 ± 0.07 μm.

Results

All droplets exhibited similar qualitative behavior. The solution spreads until reaching the maximum diameter without any measurable retraction. At this point, the contact line appeared pinned with some oscillation in the contact angle presumably due to the formation of a shallow rim. No top–down views of the droplet were collected, making it challenging to observe the rim. No splashing was observed for the conditions reported. Lower concentrations of polymer and higher droplet heights did result in splashing. The threshold for splashing for 30 wt% polymer concentration droplets was 425 mm, but splashing thresholds for other polymer concentrations were not quantified since splashing was not the focus of this work. The final droplet diameter was examined in more detail.

Final spreading ratio trends

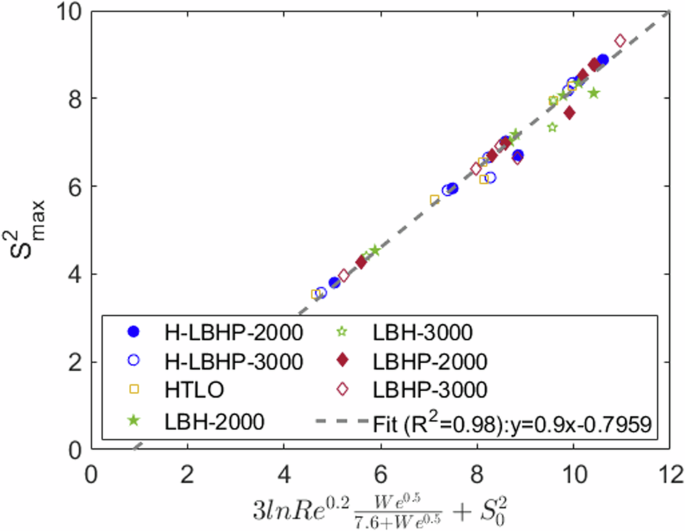

Recent work by Liu et al. provided an adjusted correlation of the maximum spreading ratio based on the non-Newtonian Reynolds number (Eq. (2))15. In that work, the maximum spreading ratio and the final spreading ratio after retraction were different, which differs from the current results. The plot shown in Fig. 2 compares the measured maximum spreading ratio to the correlation in Eq. (2). The correlation holds relatively well at spreading ratios less than 4 but shows an increase in deviation from the correlation above that spreading ratio. A similar plot with the Newtonian Re instead of the non-Newtonian Re, using the infinite shear viscosity is shown in Fig. 3. The results show that the correlation with a Newtonian Re is a better fit, even at high spreading ratios, as supported by the R2 of 0.88 and 0.98 for the non-Newtonian Re and Newtonian Re, respectively. This observation suggests that the non-Newtonian, specifically shear thinning, behavior is not dominating the spreading dynamics.

In the current study, the final (S0) and maximum (Smax) droplet spreading ratios have the same value.

In the current study, the final (S0) and maximum (Smax) droplet spreading ratios have the same value.

The Re scaling derived by Liu et al. for power-law fluids assumes that the power-law behavior is valid over the whole range of shear rates present during droplet spreading. The shear rate magnitudes (Eq. (4)) from image analysis suggest that the shear rate magnitude for the droplets studied here is greater than the shear rate at which infinite shear viscosities are reached. In fact, the shear rates near the droplet surface interface will likely far exceed this estimate21. These shear rates indicate that the droplet spreading occurs with fluid dynamic conditions that are outside the power law regime (i.e., with infinite shear viscosity). This finding agrees with previous work of blood simulants9, which showed that the infinite shear viscosity was reached during spreading and thus the spreading event was characterized by Newtonian-like behavior.

Temporal spreading dynamics

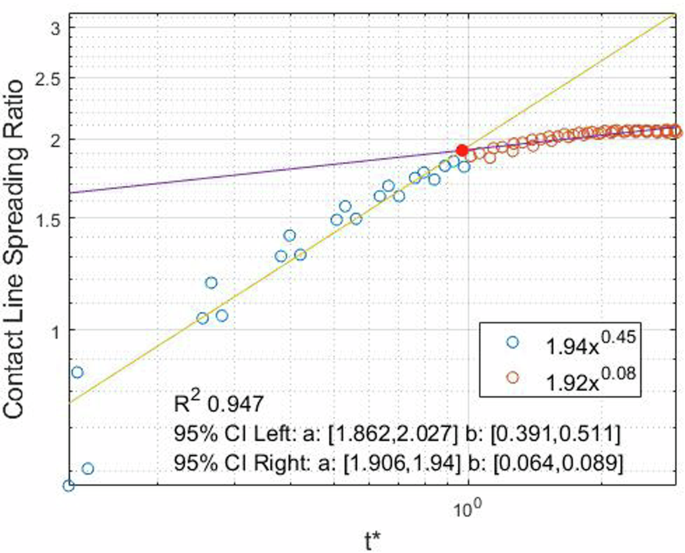

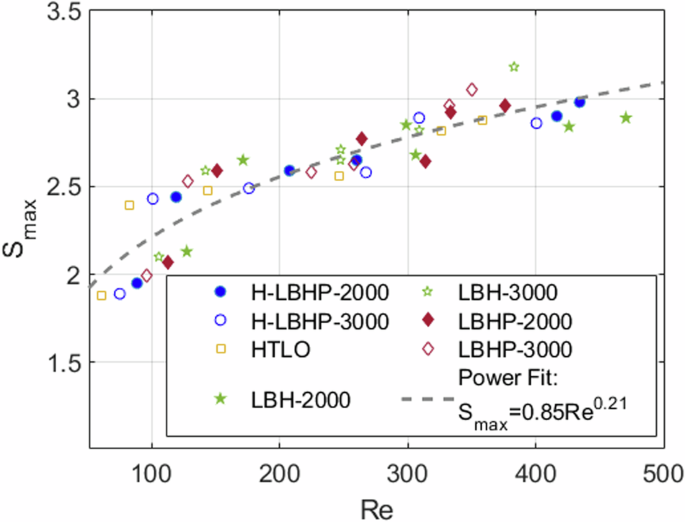

To justify the assumption that the spreading is dominated by Newtonian-like behavior due to reaching the infinite shear viscosity, we examined the temporal dependence of the spreading ratio for the seven HTPB formulations at 30 wt% in n-dodecane. We focused on the 30 wt% in this analysis because the behavior at low polymer concentrations is more likely to be dominated by the solvent and thus the higher concentrations are more at risk to deviate from Newtonian behavior. The spreading ratio as a function of time for a representative experiment is plotted in Fig. 4 and fit by two power functions: one from impact to time at which 90% of Smax is reached ({t}*_{90}) and the second from ({t}*_{90}) to ({t}*{=}{3}.) The spreading event was split into two regions to account for a change in the dominant processes. The Reynolds number for this study varied range from 50 to 500. These values suggest that inertia-dominated spreading will be important early in the spreading event. As spreading velocity slows down later in the event, the dominating processes will change. A power law fit of all maximum spreading data, Fig. 5, provides an exponent of 0.21 (R2 = 0.82). A similar R2 value was achieved when data were specifically fit to an exponent of 0.2. This value agrees very well with previous work13 and is evident of viscous-dominated spreading for later in the event. This insight justified the two-region analysis and suggests the differences in droplet spreading are due to viscosity differences for each polymer and concentration. A sharp cutoff time was not evident since realistically there will be some transition period. Since all droplet data indicated similar physics was present for all conditions, a consistent cutoff time (non-dimensional) was determined to avoid bias in the analysis. The ({t}*_{90}) value was determined through trial and error to achieve the best fits in each region and based upon consistency among all experiments. Furthermore, the spreading velocity decreased from the order of 1 m/s to the order of 0.1 m/s for most conditions near this time indicating a large decrease in droplet inertia and providing a physical justification for this value.

The transition point between inertia and viscous regimes was determined to occur near ({t}*) of 90% of the maximum spread.

Maximum spreading ratio as a function of Re and the corresponding power fit indicating viscous effects dominate over capillary forces.

The fit to data early in the event scales as approximately t0.5 as listed in Table 2. This temporal dependence is indicative of inertia-dominated spreading16. All HTPB solutions at each drop height exhibited similar temporal dependence in the early stage as indicated by the values in Table 2. The uncertainty is based upon sample-to-sample variation (at least two samples for each condition) for a 95% confidence interval. Only two exceptions deviated from that temporal dependence (i.e., outside of uncertainty bounds): 30 wt% LBH2000 at 50 mm (power law exponent of 0.42 ± 0.05) and 266 mm (0.87 ± 0.27). The 50 mm case may be due to the difference between early-time dynamic and equilibrium static contact angles. The difference at 266 mm is not clear, but given the large uncertainty value, it may be a goodness of fit issue.

The rate of spread decreases in the later time interval indicating that inertia is no longer dominating the event. As discussed previously, data in Fig. 5 indicated that viscous effects were important, and this observation agrees with the weaker time exponent in the late time regime. The specific temporal exponent for spreading diameter within the viscous spreading regime depends on the fluid rheology, specifically whether the material response is Newtonian (exponent equal to 0.1), shear-thinning (exponent less than 0.1), or shear thickening (exponent greater than 0.1) as indicated by Eq. (3). The actual temporal exponent for the shear thinning and thickening cases depends on the viscosity shear rate exponent for a power law fluid. A summary of the viscous temporal exponent data is listed in Table 2. For clarity, the viscous temporal exponent refers to the power fit exponent (i.e., the entire exponent in Eq. (3), not just n) for fitting the droplet spreading data over time. All 50 mm height data have a viscous temporal regime exponent less than 0.1, which indicates shear thinning behavior. However, the 266-mm and 425-mm droplet height viscous temporal regime fits are all near 0.1 within the 95% confidence interval (based upon sample-to-sample variation), which indicates Newtonian behavior.

These results suggest that the shear rates in the spreading flow at these higher impact velocities are greater than the shear rate at which the infinite shear viscosity is reached and the fluid is displaying Newtonian behavior at this point. It should be noted that the use of Newtonian in this context is specific to the conditions where the temporal exponent was 0.1 since other conditions exhibited non-Newtonian behavior. This result justifies the use of the infinite shear viscosity for the correlation shown in Fig. 3. As such, these droplets behave like Newtonian materials at the high shear rates reached at the end of spreading despite having shear-thinning effects at lower shear rates. This analysis is consistent with earlier discussions and the literature9.

Spreading ratio model

The Newtonian-like behavior suggests that the energy consumed from viscous dissipation will be proportional to the infinite shear viscosity as a first-order approximation since the flow is Newtonian. The flow in some regions of the droplet (i.e., away from the interface) will have lower shear rates where shear-thinning effects are present. The droplet energy from the moment just before impact (i.e., kinetic and surface energy) will be equal to the energy at maximum spreading (i.e., increase in surface energy) plus the viscous losses as shown in Eq. (1). Viscous dissipation for an incompressible, Newtonian fluid is proportional to the stress tensor (τ = μσ, where σ is the deviatoric stress tensor related to velocity gradients) and thus viscosity25. After writing Eq. (1) in terms of Smax:

The first term on the left is We/2 at impact. Solving for ({S}_{rm{max}}^{2}),

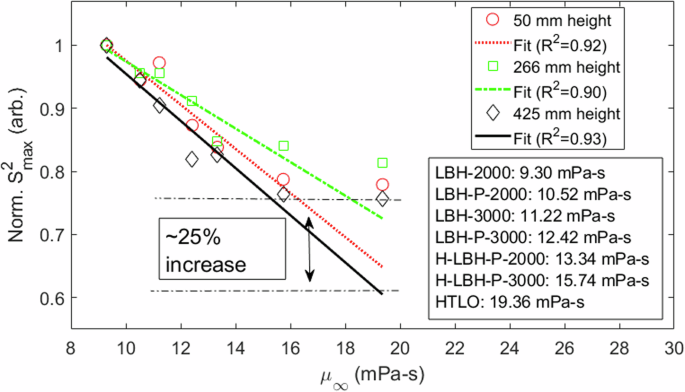

All droplets have the same initial diameter, very similar densities and surface energies, and pre-impact velocity (i.e., We) for a given initial height. The shape factor, C, may differ slightly for each spread droplet, but the differences will be small (i.e., assuming the shape is a spherical cap, C varied between approximately 0.78 and 0.84). The velocity profile and fluid element strain both realistically differ for each condition but will likely be on the same order of magnitude for a given impact velocity (i.e., droplet height). In other words, all 30 wt% droplets, regardless of polymer, will only differ in terms of the viscosity and ({S}_{rm{max}}^{2}) in Eq. (7) for a specific initial height. Therefore, one would expect a decrease in the final spreading ratio that corresponds to an increase in the infinite shear viscosity (and vice versa) from a first-order approximation. This analysis thus provides us with an excellent opportunity to evaluate how the polymer properties impact the droplet spreading through their impact on the infinite shear viscosity.

For the 30 wt% samples, the only difference in the solutions that will change the infinite shear viscosity is the polymer itself (molecular weight and branched vs linear architecture). Polymer molecular weight and degree of branching are known to change the viscosity of concentrated polymer solutions through their effects on entanglements in the polymer chains and friction between the polymer and solvent26,27. Fig. 6 shows the normalized spreading diameter squared (related to the change in surface energy as described above) against infinite shear viscosity for each drop height. The infinite shear viscosities correspond to the different polymer solutions, with the key shown in Fig. 6. The normalization is the ({S}_{rm{max}}^{2}) for each case divided by the ({S}_{rm{max}}^{2}) for the lowest viscosity solution (LBH 2000 polymer). A linear fit was applied for each droplet height, but the most viscous samples (HTLO polymer, the only branched sample) were not included in the fit. The inclusion of the HTLO droplet data greatly reduced the goodness of fit and will be discussed separately later. The remaining samples showed a high degree of correlation between the infinite shear viscosity and final surface area (R2 > 0.90), as expected based on Eq. (7). This result suggests that differences in spreading for the linear polymer-containing solutions whose infinite shear viscosities were less than 16 mPa-s are due to differences in the viscous dissipation.

The most viscous samples are HTLO. The viscosity vs shear rate curves are shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S1.

The most viscous HTLO-containing droplet impact tests do not follow the same trend for ({S}_{rm{max}}^{2}) dependence on the viscosity. This observation is likely due to the branched structure of the HTLO polymer, whereas all other polymers are linear. This property can alter the conformation of the polymer chain and how it stretches under flow. The data points for HTLO in Fig. 6 indicate that less energy than expected is consumed by viscous effects, which enables the droplet to spread further than if it followed the linear dependence on infinite shear viscosity of the other polymer solutions, increasing the final surface area. The 425 mm height data indicates that about 25% more surface area is formed than expected compared to the trend composed of the linear polymer only. The lowest difference is the 266 mm height, which showed an approximately 17% difference.

Discussion

There are likely two contributions to the enhanced spreading of the HTLO, which is branched, compared to the linear polymer solutions. The first is related to the adhesion and adsorption of the polymer onto the surface and the second is related to the behavior of the molecules during the extensional flow. Static contact angles are known to decrease with an increase in branches of a star polymer28. This observed behavior for star polymers, as well as branched and dendritic polymers, is the result of a lower entropic cost for adsorption onto the surface29. Linear polymers, especially under high shear in the flow, will need to be reoriented for the OH functional group at the end of the chain to adsorb to the surface. Branched polymers have many locations where the terminal hydroxyl groups can interact with the surface, leading to more favorable adsorption. Increased adsorption lowers the effective polymer concentration in the spreading fluid and thus decreases the bulk solution viscosity. Zero-shear viscosity measurements for both HTLO and LBH-2000 shown in Fig. 7 indicate that the viscosity decreases with decreasing concentration for the polymer solutions studied. This aspect leads to the droplet spreading behavior being more like a lower viscosity droplet over time and since the maximum spreading is also the final spreading ratio, this thermodynamic aspect is likely playing an important role. In this scenario, branched or star polymer structures may be more advantageous to increase spreading.

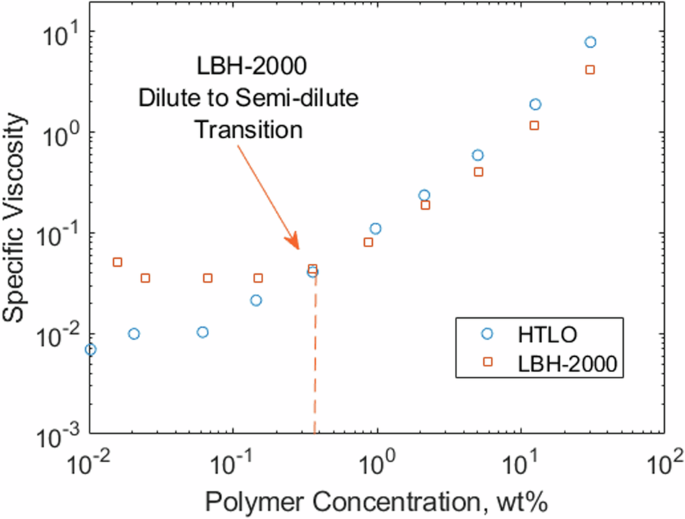

The slope break on the log–log plot for LBH-2000 indicates a transition from the dilute to the semi-dilute regime. No clear slope break was apparent for HTLO.

The other contributing factor is less clear as the behavior of polymers under extensional flow, such as that experienced during spreading, is still an active research area30,31. One potential explanation is that the linear polymer has a larger radius of gyration (Rg) than the branched polymer, especially as it can stretch more under flow. For a given molecular weight, a branched polymer is known to have a smaller hydrodynamic radius and larger molecular density than a linear polymer. The mean square radius of gyration can be estimated for linear (Eq. (8)), star (Eq. (9)), and hyperbranched (Eq. (10)) polymers based on their number of repeat units, N, and in a theta solvent and are shown below32.

with f being the number of branches or arms. Although we were unable to measure Rg for these polymers in n-dodecane, the viscosity vs concentration profiles are consistent with LBH-2000 behaving as a linear polymer and HTLO behaving as globular molecules. Fig. 7 shows the relative viscosity vs concentration for LBH-2000 up to 30 wt% and a clear transition between dilute and semi-dilute regimes is seen with the sharp change in slope at 0.37 wt%. For HTLO, on the other hand, there is no sharp transition, and it instead follows a continuous exponential trend. This concentration dependence relationship has been seen previously in globular materials that tend to associate, such as emulsions33 and monoclonal antibodies34. In both cases, the polymer solution does not reach a critical entanglement concentration, likely due to the small size of the molecules. These data indicate that the LBH-2000 is acting as a linear polymer and HTLO is acting as a globular molecule in solution.

Lu et al.32 simplified the complex hydrodynamic interactions occurring during the flow of polymers into two categories: (1) a drainage function, which describes how the solvent molecules move through the polymer, and (2) a drag function, which describes how the solvent molecules flow with the polymer. A branched polymer is denser than a linear polymer, so it is more difficult for the solvent to flow through the polymer, which can lead to higher friction working against liquid flow. However, most of the friction will come from solvent flowing on the surface of the polymer and, since branched polymers are smaller than linear polymers, there is likely to be less friction from solvent flow past the polymer molecule dissipating energy during flow. The drag function contribution to viscous dissipation will also be lower for the more globular branched polymer due to the smaller size, which leads to less solvent flowing with the polymer. With less energy lost to these hydrodynamic interactions, the branched polymer is able to spread further than expected. Although this aspect could be an explanation for how the molecular characteristics impact the flow, additional study is needed to definitively understand this complex phenomenon, especially given the high extensional flow during spreading.

It is clear that the branched polymer solution leads to a higher degree of spreading than expected based on the infinite viscosity trends seen for the linear polymer solutions. We suggest that this result is a combination of increased adsorption of branched polymers on the surface, a phenomenon that is well-understood in the literature28,29, and differences in hydrodynamic interactions between the more spread out linear polymer and denser globular branched HTLO, which is a less well-understood phenomenon. Future systematic studies of droplet spreading and extensional rheology for concentrated, unentangled polymers of different architectures could greatly increase our understanding of the mechanisms behind the behavior of different binders used during jetting.

In the context of binder jetting AM, these results present several important implications. The printing resolution will be determined by the final droplet diameter in addition to other parameters such as penetration depth that were not studied here. The variation in maximum spreading ratio did not change by more than about 5% between the different polymers used for a fixed wt% and droplet height. A decrease in polymer content for a specific polymer at 50 mm initial height resulted in the greatest change in spreading ratio. The difference between 3.85 wt% and 1.85 wt% changed on the order of 1% instead of approximately 30% as polymer content was decreased from 30 wt% to 10 wt%. The amount of polymer in each droplet will also likely affect the printing resolution in the vertical direction based on the amount of deposited material, pore geometry, etc. In general, lower molecular weight polymer droplets spread further, which is expected given the different infinite shear viscosities. The infinite shear viscosity for linear polymer chains was determined to be important in the overall dynamic wetting process for the materials studied. Branched polymers may enable better wetting as discussed here and in ref. 7 although the possible formation of associated globules may complicate modeling the deposition process. As the binder droplet penetrates the powder bed, the flow will likely be driven by capillary effects, which depend on pore shape and size. If branched polymers adsorb to the particles more readily, the viscosity of the flow will decrease. The carrier solvent may penetrate deeper in that case although future work is needed to determine these details. These aspects only consider the prepolymer without effects from curative, plasticizer, etc. As such, this work should be used to down-select initial polymer structure from a deposition perspective, particularly in directions along the powder bed. The droplet size studied had a Bond number small enough that gravitational effects would be small but are still larger than droplets used in practice. Previous work35 used millimeter-sized droplets to obtain preliminary data on binder-particle interaction. Much smaller droplets (micro to nano-scale) will be affected more by the surface roughness and particularly the porosity present in loose powder beds that are typical of PBBJ. Increased porosity and change in geometry will affect the amount of binder that penetrates the powder bed. The effective surface roughness will likely also influence the spreading dynamics. Therefore, the results presented in this work are more indicative of the fundamental spreading dynamics based on polymer structure rather than a guide for choosing specific parameters for PBBJ. Other factors may influence the final mechanical properties of the produced materials such as composite propellants, although it is believed that improved wetting will also help improve adhesion between the binder and particulate phases. Overall, here we develop important insights into the spreading behavior, which addresses one of the key phenomena in binder jetting and other applications of droplet impact and spreading. However, future studies on the inkjet-ability and curing of these low molecular weight polymer solutions will also be necessary to fully understand the process and enable improved binder material design.

Dynamic wetting of AP pellets by commercially available polybutadienes was studied. The relatively high polymer concentrations were observed to spread to a maximum without retraction and splashing for the conditions tested. The early spreading dynamics were controlled by inertia whereas later times were dominated by viscous effects as determined by known Reynolds number scaling. Shear thinning effects were only apparent for droplets from the 50 mm initial height. Increased impact kinetic energy created shear rates within the flow that led to conditions outside the shear-thinning regime and spread as expected for Newtonian fluids. This result indicated that published correlations for the maximum spreading diameter for non-Newtonian fluids should only be used when the shear rate magnitude for droplet spreading is within the shear rate range of non-Newtonian behavior. The effect of polymer structure on spreading for the polybutadienes tested was due to the solutions’ infinite shear viscosities and polymer chain interactions with the surface and other polymer chains in the flow. Specifically, the branched polymer droplets were able to spread up to 25% further, in terms of increase in surface energy used, than expected based upon analysis for linear polymers despite an increase in viscosity. This observation is due to a combination of a decreased conformal entropy penalty for surface adsorption and potential emulsion formation during spreading. These results have important implications in AM of high solids-loaded composite materials particularly in the choice and design of polymer structure.

Responses