The role of inhibitory and excitatory neurometabolites in age-related differences in action selection

Introduction

As the world population consists of an increasing proportion of older adults, understanding the processes of aging has become important from a socioeconomic perspective. Reports from the World Health Organization show that 1 in 6 people is more than 60 years old1. Aging leads to both musculoskeletal transformations and neurodegenerative alterations in the central (CNS) and peripheral nervous systems. These neural modifications have been associated with a decline in cognitive2,3 as well as motor functions4,5,6,7,8. To enhance the quality of life for older adults, a comprehensive investigation of the underlying neural mechanisms of aging in relation to motor performance is essential. Here, we focus on the effect of aging on the neurochemical processes involved in action selection.

Action selection refers to the process of selecting one out of several possible options and requires a mechanism to allocate the available neural resources efficiently based on goals and priorities9. It consists of a cognitive component that is related to the central processing of motor planning and effector selection, as well as a motor component referring to the execution of the task10,11. Together, these two components make “action selection” a prominent and vital capability in daily life.

To address and further decompose action (effector) selection, numerous reaction time tasks have been designed12,13,14,15. In such experiments, participants are requested to react to simple or complex stimuli as fast and accurately as possible. When participants react to a single, repeated stimulus, the resulting reaction time (RT) is termed simple reaction time (SRT). When they need to select an action from several possible options, the resulting RT is called choice reaction time (CRT). The SRT encompasses primarily the motor component of the task with minimal central processing since the to-be-performed task is already preselected. In contrast, CRT incorporates both motor and central processing components, as participants first need to recognize the stimulus, select the movement, and then execute the appropriate response. The difference between these two measures (i.e., CRT – SRT) provides a measure termed net reaction time (NRT), which predominantly reflects the central processing component of the task16,17.

To investigate aging-related deteriorations in action selection, Boisgontier et al.10 designed a multi-limb RT task in which the reaction times from the two hands and two feet were recorded in response to multiple visual cues. They reported that older participants were significantly slower than their younger counterparts. Moreover, age-related gray matter atrophy in the basal ganglia, specifically caudate and nucleus accumbens, was linked to longer NRT in older adults17. Inspired by this study, Rasooli et al.11 used the same task and found that age-related white matter deterioration in the prefronto-striatal structural connectivity was associated with longer NRT in older adults. More specifically, deterioration of white matter connections from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and frontal pole to the basal ganglia mediated the age-related decline in reaction time. However, while the impact of age-related deterioration of gray and white matter on action selection has been examined in detail, the role of the brain’s neurometabolites remains to be investigated.

The advent of magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) has made it possible to noninvasively measure concentrations of brain neurometabolites, such as γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate (Glu), which serve as the major inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters in the human brain, respectively. These and other metabolites play vital roles in human behavior, including motor function. While some studies have focused on the static levels of neurometabolites in motor performance and motor learning18,19, more recent studies have looked into the dynamic modulations of the MRS-assessed concentration of GABA and/or Glu during or following motor performance and learning (see further).

Concerning action selection performance, to the best of our knowledge, only one study has addressed the potential role of (the dynamics of) neurometabolites in this ability. More specifically, Maes et al.20 used a multidigit selection task in a sample of young and older adults and reported a transient decrease in the SM1 GABA concentration during action selection performance as compared to baseline. However, other brain areas also play an important role because action selection requires suppression as well as activation of distinct effectors. Given the role of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) in motor inhibition21,22, this area may be critical in the central processing component of action selection. Furthermore, because aging is associated with changes in the concentration of neurometabolites23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, the impact of age on the dynamics of neurometabolites in the presence of increased action selection demands needs to be examined.

It is also expected that the learning capacity in action selection is associated to neurometabolic mechanisms. To this regard, some studies have shed light on neurometabolic changes associated to different types of motor learning. For instance, decreases in the SM1 GABA levels were observed following training of force-tracking33, serial reaction time34, and juggling35 tasks. Such decreases in GABA are proposed to promote neural plasticity. However, Maruyama et al.36 reported that training of a sequential finger-tapping task resulted in an increase in the SM1 Glu concentration while no significant learning-induced changes in the concentration of SM1 GABA were observed. These findings appear to support the hypothesis that task-related modulation of the excitation-inhibition balance plays a key role in cortical long-term potentiation-like-plasticity37 and motor learning38,39. Nonetheless, null findings regarding neurometabolic changes in a serial reaction time task and motor sequence learning have also been reported40,41, possibly due to methodological differences across studies.

Compared to GABA, less attention has been devoted to Glu. Of note, since isolated measurement of Glu level is less reliable using the standard MEGA-PRESS MRS sequence at the 3 T, Glu + glutamine (Glx) is measured instead42. Numerous studies have reported that Glx concentrations are linked to motor performance. A higher concentration of Glx has been shown to result in greater cortical excitability, potentially facilitating motor performance and learning43. Specifically, Schaller et al.44 reported a task-induced increase in Glx level in the SM1 using a finger-tapping task. Furthermore, age-related reductions in the striatal Glx levels have been associated with poorer performance in a Grooved pegboard task25. Therefore, metabolic dynamic changes in both, GABA and Glx, may be relevant in action selection performance and learning and age-associated differences.

In the present study, our primary goal was to investigate task-induced modulations in GABA and Glx as a result of action selection performance and to examine their association with the different components of action selection (motor and central processing). Use was made of a multidigit reaction time task in young and older adults and the neurometabolic levels from two volumes of interest (VOIs, namely SM1 and dlPFC) were acquired during the resting state as well as during the performance of the SRT and CRT tasks. As a secondary goal, we aimed to explore the association between GABA and Glx modulations and the short-term motor learning capacity observed in relation to action selection.

From the behavioral perspective, we anticipated that older adults would exhibit a slower action selection performance as compared to young adults. From the neural perspective at group level, we hypothesized an increased excitatory tone in SM1 during the SRT task as compared to baseline (induced by a decrease in GABA and/or an increase in Glx), as well as an increased excitatory tone in SM1 and dlPFC during the CRT task (equally induced by a decrease in GABA and/or an increase in Glx) as compared to baseline. In terms of associations between the individual level of neurometabolites and behavioral measures, we postulated that in the SM1 area, a greater task-induced decrease in inhibition and/or a greater increase in excitation would be correlated with faster reaction times in the SRT (measuring the motor component) as well as greater motor learning in the SRT27,33,34,35,36. Regarding the dlPFC region, considering its role in attentional selection45, motor inhibition21, executive control22 and its prominent contribution to the initial phase of motor learning46,47, we expected that a greater increase in the excitatory tone (as indexed by increased Glx and/or by decreased GABA) would be associated with better (shorter) CRT (motor and central processing) and NRT (central processing) measures and their learning-induced improvement. Finally, we hypothesized the age-related differences in metabolic modulation to be associated to motor performance and learning. In summary, a task-induced increase in excitatory tone was predicted to promote task performance and learning.

Results

Behavioral task performance

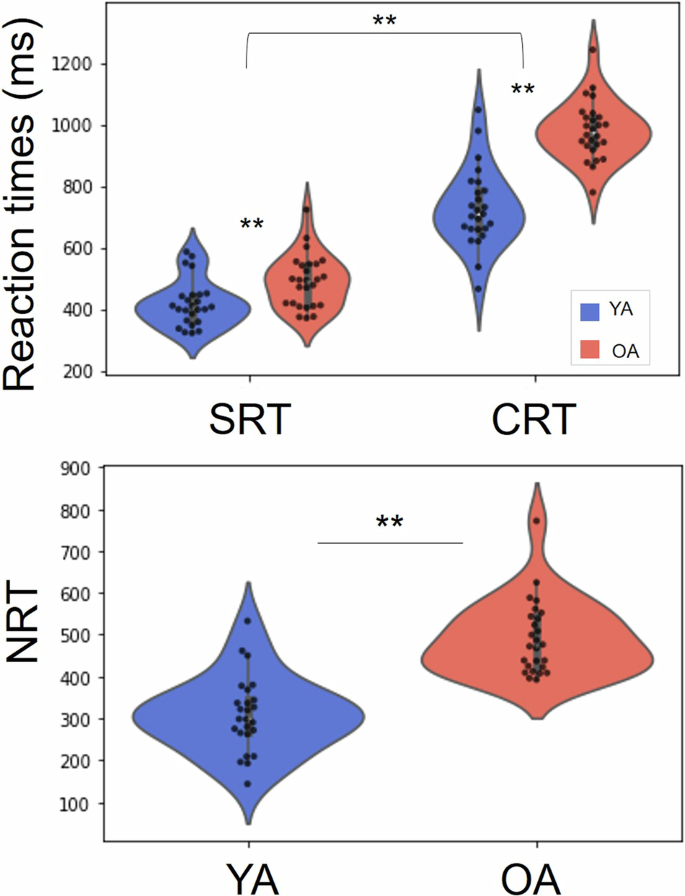

Results of the 2 × 2 mixed model ANOVA test, examining the impact of Age group (YA vs OA) and Stimulus condition (SRT vs CRT) on reaction time revealed an effect of Age (F(1,49) = 60.35, p = <0.001, ƞp2 = .55), with YA reacting faster than OA in all conditions. The same analysis also revealed an effect of Condition (F(1,49) = 852.66, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = .95), with participants reacting faster in the SRT as compared to the CRT condition. Finally the interaction effect (Age × Condition) was also significant (F(1,49) = 33.66, p < 0.001, ƞp2 = .41) with the age difference being more pronounced during the CRT condition (Fig. 1).

Older adults took longer to execute the movements from the Simple (SRT) and Choice (CRT) Reaction Time tasks, with this difference being more pronounced in the CRT (top panel). Likewise, older individuals had a longer central processing time, measured by the Net Reaction Time (NRT). Significant differences are marked with **(p < .0.01).

Control analyses showed that SRT, CRT and NRT were not significantly different according to the order in which they were measured across individuals (SRT SM1: F(3,47) = 0.88, p = 0.45, ƞp2 = 0.05; SRT dlPFC: F(3,47) = .79, p = .51, ƞp2 = 0.05; CRT SM1: F(3,47) = .88, p = .46, ƞp2 = .05; CRT dlPFC: F(3,47) = .06 p = .97, ƞp2 = .004; NRT SM1: F(3,47) = .48, p = .69, ƞp2 = .03; NRT dlPFC: F(3,47) = .48, p = .69, ƞp2 = .03).

Resting-state (baseline) concentrations of neurometabolites

GABA concentrations

Results of the 2 × 2 [Age group (YA vs OA) x VOI (SM1 vs dlPFC)] mixed model ANOVA revealed significant main effects of Age group (F(1,49) = 23.316, p < .001, ƞp2 = .234) and VOI (F(1,49) = 22.387, p < .001, ƞp2 = .141), indicating that the overall GABA concentrations were higher in YA as compared with OA, and GABA concentration was higher in the SM1 as compared with the dlPFC VOI (Young GABA M1: mean = 2.88, sd = .21; Old GABA M1: mean = 2.57, sd = .31; Young GABA dlPFC: mean = 2.65, sd = .21; Old GABA dlPFC: mean = 2.39, sd = .31).

Glx concentrations

Results of the 2 × 2 [Age group (YA vs OA) × VOI (SM1 vs dlPFC)] mixed model ANOVA demonstrated significant main effects of Age group (F(1,49) = 37.909, p < .001, ƞp2 = .328) and VOI (F(1,49) = 137.804, p < .001, ƞp2 = .510), indicating that Glx concentrations were higher in YA as compared with OA, and higher in the dlPFC as compared with the SM1 VOI (Young Glx M1: mean=7.92, sd = .45; Old Glx M1: mean = 7.16, sd = .56; Young Glx dlPFC: mean = 9.11, sd = .56; Old Glx dlPFC: mean = 8.29, sd = .71).

Modulations of neurometabolites

GABA modulation

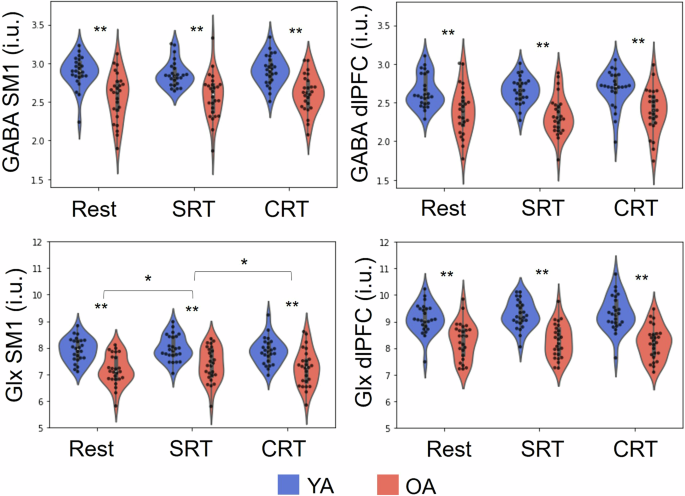

Results of the 2 × 3 × 2 [Age group (YA vs OA) × Task (Resting state, SRT, and CRT) × VOI (SM1 vs dlPFC)] mixed model ANOVA on the concentrations of GABA showed significant main effects of Age group (F(1,49) = 35.271, p < .001, ƞp2 = .275) and VOI (F(1,49) = 60.849, p < .001, ƞp2 = .171), indicating that concentrations of GABA were higher in YA as compared to OA in all of the task conditions, and were higher in the SM1 as compared with the dlPFC voxel (Fig. 2). However, the main effect of Task (F(2,98) = 1.978, p = .150, ƞp2 = .006) and the interaction effects of Task × Age group (F(2,98) = .128, p = .857, ƞp2 < .001), and Age group × Task × Voxel (F(2,98) = .561, p = .559, ƞp2 = .002) were not significant. These findings indicated that changes in the GABA concentrations in response to the task execution were not significantly different between tasks (Fig. 2).

GABA and Glx concentrations in the SM1 and dlPFC voxels of interest as measured during resting state, SRT task performance, and CRT task performance in young (YA) and older adults (OA). SRT: simple reaction time, CRT: choice reaction time, SM1: sensorimotor cortex, dlPFC: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, i.u.: institutional units. Significant differences are marked with a *(p < .05) and **(p < .01).

Glx modulation

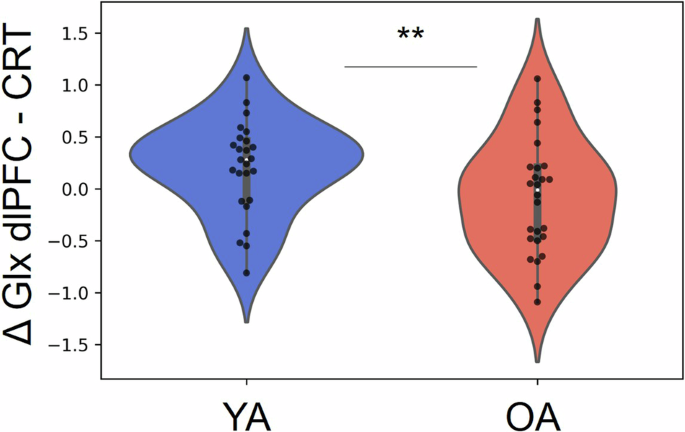

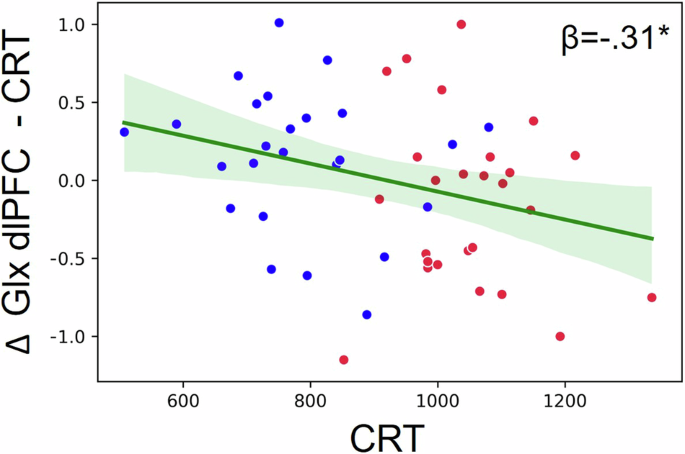

Results of the 2 × 3 × 2 [Age group (YA vs OA) × Task (Resting state, during-SRT, and during-CRT) × VOI (SM1 vs dlPFC)] mixed model ANOVA indicated significant main effects of Age group (F(1,49) = 41.444, p < .001, ƞp2 = .334) and VOI (F(1,49) = 204.192, p < .001, ƞp2 = .493). Thus, concentrations of Glx were higher in YA as compared to OA and were higher in the dlPFC as compared to the SM1. However, while the main effect of Task (F(2,98) = 2.839, p = .066, ƞp2 = .005) and the interaction effect of Age group × Task (F(2,98) = .471, p = .617, ƞp2 = .001) were not significant, the interaction effect of Age group × Task × Voxel (F(2,98) = 3.167, p = .05, ƞp2 = .006) was significant. In the SM1 voxel, a significant main effect of Task was observed (F(2,98) = 4.137, p = .022, ƞp2 = .013). Posthoc analyses indicated significantly higher levels of SM1 Glx during the SRT as compared to the Rest condition (t = -2.96, gl = 50, p = .005, d = -.41) and also as compared to the CRT condition (t = 2.43, gl = 50, p = .02, d = .33). However, the SM1 Glx levels during the CRT did not significantly differ from baseline levels (t = -.09, gl = 50, p = .92, d = -.01). The interaction effect of Age group × Task was not significant (F(2,98) = .972, p = .376, ƞp2 = .003). In the dlPFC voxel, results of the post-hoc analysis revealed neither a significant main effect of Task (F(2,98) = .541, p = .578, ƞp2 = .002) nor an interaction effect of Age group × Task (F(2,98) = 2.406, p = .097, ƞp2 = . 009). In sum, Glx concentrations were higher in younger adults as compared to older adults, were higher in the dlPFC as compared to the SM1 and were higher during the SRT condition as compared to Rest and CRT in the SM1 voxel (Fig. 2). Complementary analyses examining whether there were differences in the absolute metabolic modulations (magnitude of task-induced changes) between young and older adults, revealed no significant differences (Table S1), except for the modulation of Glx in the dlPFC during the CRT in reference to baseline (t = -2.001, p = .05, d = -.56), with the young adults showing an average metabolic increase (mean = .21, sd = 45) and older adults showing on average a decrease (mean = -.08, sd = .55; Fig. 3).

Younger individuals showed on average an increase in Glx from the dlPFC during CRT (as compared to baseline) which significantly differed from the modulation observed in older adults, who showed on average a slight decrease.

Brain-behavior associations

Modulation in neurometabolites predicting task performance

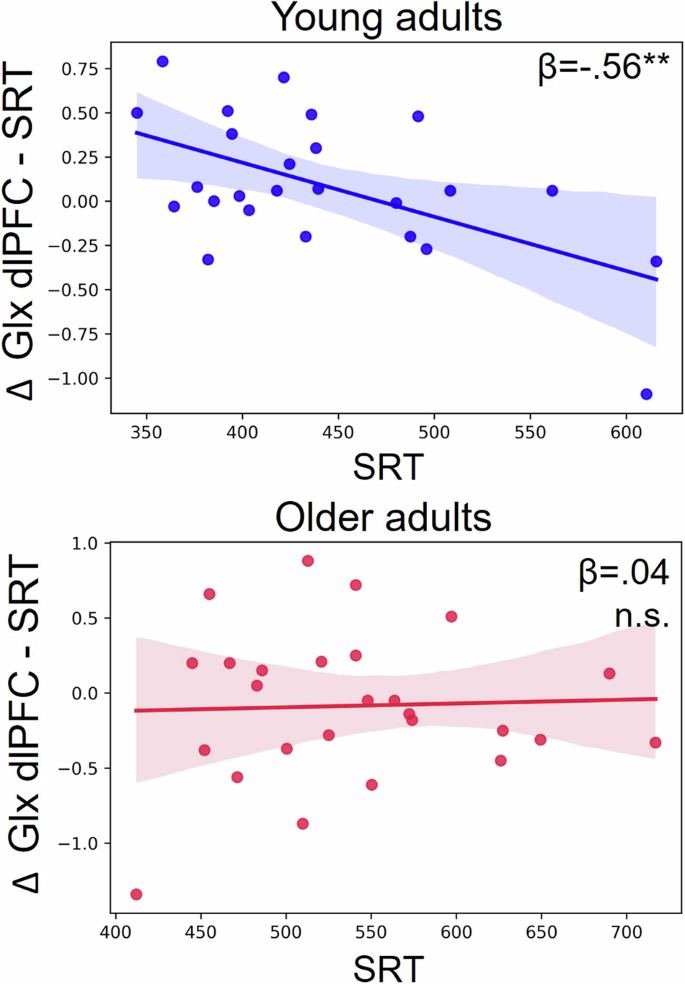

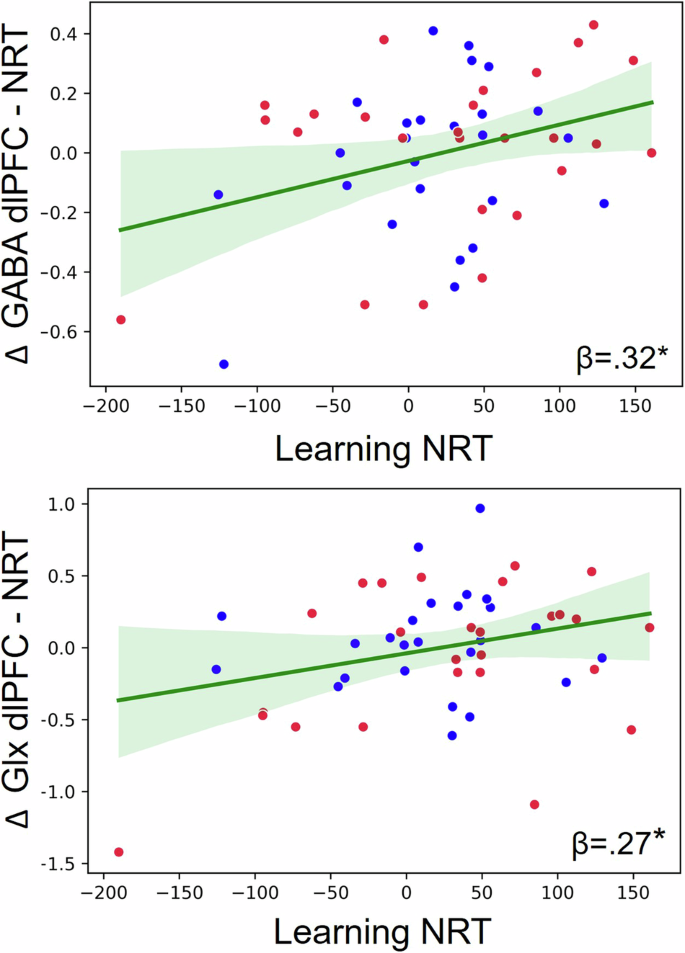

Multiple linear regression analyses predicting behavioral indices based on metabolic modulations (task-induced changes in GABA and Glx) and their interaction with age showed that the Glx modulation in the dlPFC during the SRT task (with baseline as reference) and its interaction with age predicted the SRT performance (R2 = .16, F = 4.78, p = .01; Table 1). When testing the predicting value of Glx modulation in dlPFC in independent analyses per age group, this variable was a significant predictor in young individuals, indicating that an increase in Glx was related to a faster performance (R2 = .32, F = 10.75, p = .003; LI: -170.61, LS: -38.61; Table 1; Fig. 4), but no significant effect was observed in older individuals (R2 = .002, F = .04, p = .84; Table 1; Fig. 4). The Glx modulation during the CRT (with baseline as reference) in the dlPFC predicted the CRT performance in the full sample, once more with an increase in Glx indicating a faster performance (R2 = .07, F = 5.07, p = .03; CI:[-198.29, -11.27]; Table 1; Fig. 5). However, given that young and older adults differed in the dlPFC Glx modulation during the CRT (with baseline as reference), we tested whether the association between this variable and CRT performance was explained by age, which was actually the case (r = -.16, p = .28). The modulation of GABA and Glx in SM1 and the modulation of GABA in the dlPFC did not have any predictive value in these models.

The modulation of Glx in the dlPFC during the SRT condition (task-induced changes in Glx during the SRT as compared to baseline) predicted the performance in young individuals (an increase in Glx related to a faster performance; top panel) but not in older individuals (bottom panel).

The modulation of Glx in the dlPFC during the CRT condition (task-induced changes in Glx during the CRT compared to baseline) predicted the CRT performance in the full sample (an increase in Glx related to a faster performance). However, this association was mediated by Age group (see text). Blue dots represent young individuals and red dots represent older individuals.

Finally, there were no significant predictors for the NRT performance (R2 = .09, F = .56, p = .81; Table 1).

Modulation in neurometabolites predicting motor learning

The multiple linear regression analyses to predict the degree of motor learning in SRT and CRT (with baseline as reference) through metabolic modulations did not show any significant predictors (SRT: R2 = .18, F = 1.21, p = .32; CRT: R2 = .02, F = 1.11, p = .37; Table 2). However, the Glx and GABA NRT modulation (metabolic change during the CRT in reference to the SRT) in the dlPFC were significant predictors of the NRT learning in the full sample. Both, an increase in GABA and an increase in Glx in the dlPFC related to an improvement in the NRT measure (i.e. shorter central processing time) (R2 = .18, F = 5.45, p = .007; Δ GABA dlPFC (CRT-SRT) CI:[15.28, 158.62]; Δ Glx dlPFC (CRT-SRT) CI:[1.62, 89.96]; Table 2; Fig. 6).

The modulation of Glx and GABA in the dlPFC for the NRT component (task-induced metabolic changes during the CRT in reference to the SRT) predicted a behavioral improvement in the NRT component (central processing) in the full sample. Blue dots represent young individuals and red dots represent older individuals.

Discussion

We investigated the role of inhibitory and excitatory mechanisms in the motor and central processing components of action selection in young and older adults. We hypothesized an increased excitatory tone in SM1 associated to the execution of the motor component (SRT) and increased excitatory tone in dlPFC associated to the involvement of the central component (CRT and NRT). Whereas we observed an increase in Glx from SM1 in the full sample during the SRT in reference to baseline in the full sample, we did not observe significant differences in the metabolic activity in the dlPFC during the performance of the CRT in reference to baseline nor in reference to the SRT.

In terms of the association between individual neurometabolite modulations and action selection performance, we did not observe any associations between behavior and metabolic modulation in the SM1. In contrast, we observed that an increase of Glx in the dlPFC during SRT (in reference to baseline) related to a faster SRT performance in young adults and that an increase of Glx in dlPFC during CRT (in reference to baseline) related to a faster performance in action selection with a choice component (CRT) in the full sample. Last, we observed in the full sample that an increase in GABA and Glx in the dlPFC predicted a reduction in the central processing time (NRT learning). These findings deepen our understanding of the neurometabolic modulation mechanisms during action selection.

In regard to the behavioral analyses, our findings consistently revealed that older adults exhibited slower response times as compared to young adults across the different action selection components. This finding is in line with the previous evidence reporting a significant age-related decline in action selection performance for larger limb segments (than the finger responses used in the present task)10,11.

In relation to baseline neurometabolite levels, in both regions, the dlPFC and SM1, a lower concentration of GABA and Glx was observed in the older adults as compared to young adults. These findings align with a substantial body of literature reporting a decline in GABA and Glx concentrations associated with the aging process23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,48,49. Age-related declines in the number of GABAergic interneurons50,51 and a reduction in the glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), which is the enzyme responsible for GABA production52, have been proposed as the possible biological mechanisms underlying the observations of age-related decline in the MRS-assessed GABA concentrations32.

According to our hypothesis, we observed an increased excitatory tone in SM1 associated to the execution of the motor component (SRT) in reference to baseline, through the increase of Glx. This observation was observed in the full sample. Maes et al.20 showed a decrease in GABA in the same region as a result of motor performance. In contrast to the SRT execution, Maes et al.20 observed this finding during an action selection task that involves a motor and central processing component. Moreover, whereas in the current study individuals exerted continuous pressure on their fingers prior to selective release in the current study, individuals needed to press down the fingers to execute the required movement in the study of Maes et al.20. As the difference in the exertion of pressure may induce changes in the excitatory tone53, this could partially explain the differences between both results. Nonetheless, Schaller et al.44 observed an increase in glutamate during a finger to thumb tapping task (which required minimal central processing and minimal pressure exertion). Therefore, we are tempted to conclude that the pressure exertion by the fingers may not have been sufficient to explain the difference between the findings of Maes et al.20 and ours.

Surprisingly, Glx levels in the SM1 were lower during the CRT task as compared to the SRT (and were similar to those observed during baseline). In contrast to the SRT task, which required the continuous release of the same finger(s) from trial to trial, the CRT task required continuous motor reconfiguration across the different trials during the block, which may result in a diminished excitability as compared to the SRT.

Given the role of dlPFC in motor inhibition and executive control21,22, we had hypothesized an increased excitatory tone associated to the execution of the central processing component in reference to baseline and to the execution of the motor component alone in this region. However, no significant task-induced neurometabolic modulations were identified in the dlPFC region at the group level. One possible cause could be that the MRS voxel size might include other subregions besides the dlPFC. In addition, it has been reported that the activation of the dlPFC in relation to motor cognition, is mostly consistent during motor imagery and inconsistent during motor execution, which may indicate that this region is active when the mental load is high54. It may be possible that the cognitive demand in the CRT task was not high enough to induce measurable metabolic changes in this region through the current methods at the group level. It is also important to note that null findings regarding metabolic changes across behavioral conditions (at the group level) are not uncommon and that individual differences may play a major role, as shown by frequent associations between metabolic modulation and behavioral performance as shown in previous studies36,40,41,48 and in the current one.

Whereas there were absolute metabolic modulations in SM1 (Glx change among conditions within the full sample), individual neurometabolic modulations in SM1 did not predict behavioral performance in the motor component of action selection (SRT), contrary to what we had hypothesized.

In contrast, we observed that an increase of Glx in the dlPFC during the execution of the motor component of action selection (without the choice component and in reference to baseline) was related to a faster execution in young adults. An increase in Glx in the dlPFC reveals an increased excitability, which may enhance neural activity in the dlPFC. Although there was no choice required during the SRT, it is possible that the motor coordination still engaged a minimal degree of executive control. Whereas there were no absolute metabolic changes in the dlPFC among conditions at the group level, the present findings revealed that individual differences in the metabolic modulation of this region relates to the performance level on the motor component of action selection in young adults. The effect of Glx modulation in the dlPFC on motor behavior (no choice) observed only in young adults may indicate that such modulation in young individuals -possibly by having higher default Glx availability- has the potential to boost performance speed.

Although we observed that an increase of Glx in the dlPFC during action selection with the choice component (in reference to baseline) related to a faster performance in the full sample, this finding was mediated by age, with younger individuals having a higher increase in Glx in the dlPFC during the CRT (in reference to baseline) than older adults. Therefore, whereas younger adults have a higher increase of Glx in the dlPFC during action selection, this does not seem to directly relate to the level of performance.

Contrary to what we had hypothesized, the metabolic modulation in the dlPFC was not related to measures associated with the central processing time. It may be possible that the metabolic differences between the SRT and CRT conditions (reflecting NRT modulation) were not sufficient to detect a modulation specific to the central processing component of task execution. In addition, it is important to note that we only measured the metabolites in the left hemisphere while the central processing component may solicit neural activity in both hemispheres (particularly for bimanual responses) and, in turn, may be the result of the metabolic dynamics among both hemispheres (involving metabolic transcallosal activity).

Even when no metabolic modulation predicted the level of performance in the central processing component, metabolic modulation in GABA and Glx predicted the improvement of performance in this component (i.e. short-term learning). Specifically, in the full sample an increase in GABA and Glx in the dlPFC during action selection with a choice component (in reference to motor behavior without a choice component) predicted a reduction of the central processing time (NRT), this is, in the time that the individual takes to select, plan and coordinate the motor behavior. As mentioned earlier, the dlPFC is an important region in motor inhibition21,22, and is also involved in motor sequence learning55 and learning other types of tasks56,57. To our knowledge only two studies have reported an association between individual differences in metabolic modulation and motor learning. These studies reported an improved performance in motor sequence learning associated to a decrease in GABA in the SM136,41. Our study differs in two major points: a) we observed the metabolic modulation-behavioral performance association in the dlPFC, and b) our motor task did not imply motor sequence learning but finger coordination learning instead. Other studies have associated an increase in GABA in different brain regions after audiomotor learning58, visual overlearning59, visual discrimination learning60 and conflict resolution through a Stroop task61. Based on these observations, Li et al.62 have proposed the GABA increase for better neural distinctiveness hypothesis, which proposes that an increase in GABA favors the discrimination of subtle perceptual differences and possibly supports building distinct perceptual neural representations. In the context of this study, GABA would be supporting the discrimination and the neural representation of the finger movement compositions.

Although a simultaneous increase of Glx and GABA related to central processing learning may seem counterintuitive at first glance, different factors can possibly account for this finding. It may be possible that action selection learning benefits from a continuous interplay of GABA and Glx, which are modulated at different timepoints and even on different neural populations across the sensoriomotor cortex covered within the measured voxel, but, given the low temporal resolution of MRS, only an average increase in both GABA and Glx is observed. Whereas Glx may be keeping those neural populations active, GABA would be favoring their selective activation on the temporal and spatial (regarding the selection and execution of different fingers) domains, supporting motor discrimination and a consequent improvement in coordination. Future event-related fMRS designs could test these hypotheses.

In sum, we examined the neurometabolic modulations associated to the performance and learning of action selection. Specifically, we investigated GABA and Glx modulations in SM1 and dlPFC associated to the motor and central processing components of action selection.

When examining absolute metabolic modulations among conditions (group level), we observed a metabolic modulation of Glx in the SM1 in the full sample, but we did not observe absolute modulations in GABA (from either region) or Glx from the dlPFC. In contrast, when looking at individual differences in modulation and their relation with behavior, we observed that a task-induced increase in Glx in the dlPFC related to a faster performance in SRT (young adults). Moreover, metabolic modulations in GABA and Glx in the dlPFC predicted a training-induced reduction in the central processing time in the full sample, indicating the importance of metabolic modulation in dlPFC in action selection learning.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate neurometabolic modulations related to the performance and learning of different components of action selection. Our findings showed distinct metabolic modulations in the execution and learning of different components of action selection and underscore the impact of aging on action selection performance and their associated dynamic neurochemical mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Participants

Fifty-four healthy adults, including 26 young participants (mean ± SD: 26 ± 4.07, age range: 18-35) and 28 older participants (mean ± SD: 70.24 ± 3.99, age range: 60-80) with normal or corrected-to-normal vision were recruited. Participants were recruited through advertisement posters in the university, social centers and an e-mail list of participants from previous studies. All the participants were right-handed, according to the Edinburgh Handedness questionnaire63 (Oldfield, 1971), and reported no history of psychiatric and/or neuromuscular impairments. Older participants were subjected to the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) to scan for mild cognitive impairment (MCI). All participants scored above the cutoff point (24)64, indicating no MCI. Beck’s Depression Inventory was used to assess the individuals’ level of depression65. Moreover, participants’ alertness during the session was assessed using the Stanford Sleepiness Scale (SSS66) at the start of each session. One older and one younger participant were not able to complete the whole experiment because of personal reasons, and one older participant was excluded because of the inability to perform the task properly. In the end, the groups consisted of: young adults (YA), n = 25, 13 female, age: 26.93 ± 4.78; older adults (OA), n = 26, 10 female, age: 70.45 ± 4.05). The age groups did not differ with respect to sex (χ²(1) = 0.47592, p = 0.4903).

The study was approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee of KU Leuven (study number S58333) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. All participants provided written informed consent before the start of the study and received financial compensation for participating.

Multidigit reaction time task

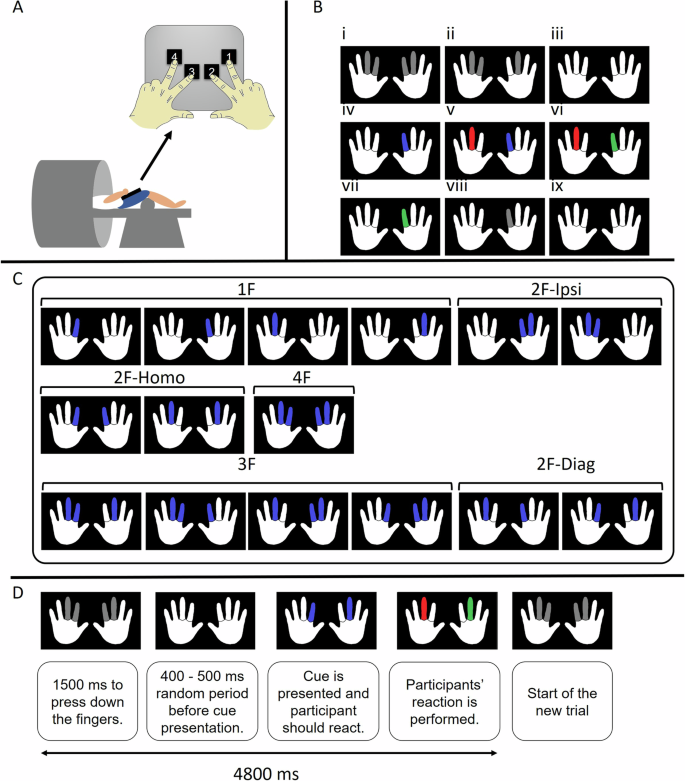

Experimental setup

We developed an action selection task to evaluate the selectivity of unimanual/bimanual motor responses20. The task was performed on a specialized MR-compatible keyboard with four keys corresponding to two index fingers and two middle fingers (Fig. 7A). During the MRI session, participants were in a supine position with a cushion underneath the knees such that the task apparatus could be placed on their lap (Fig. 7A). The apparatus was positioned such that participants flexed their elbows at ∼135°, allowing the upper arms to rest on the MRI table. If needed, cushions were provided underneath the upper arms or apparatus to ensure maximal comfort. The participants were instructed to keep all four buttons pressed and, upon the intention of reacting with a specific finger, release the corresponding button. The task was shown with an LCD projector (NEC PA500U, 1920 × 1200 pixels) onto a mirror positioned in front of the participant’s eyes.

A Participants were positioned supine in the MR scanner and the task apparatus was placed on their lap. The task apparatus was a specialized MR-compatible keyboard with four keys corresponding to two index fingers and two middle fingers. B Exemplar multidigit reaction time task trial procedure. i, At the beginning of each trial, when the buttons are not pressed with the corresponding fingers, all the cues are gray. ii, The cues turn white as soon as the corresponding buttons are pressed. iii, The setup is ready for a trial when all the buttons are pressed with their corresponding fingers. Participants have 1500 ms for this preparation, otherwise, the trial is considered “aborted”. iv, After a randomly varying jitter time ranging from 400 to 500 ms, the stimuli are presented as blue finger(s), indicating the fingers that should be released as quickly and correctly as possible. v, If the participant releases incorrect finger(s), the corresponding cue(s) turn(s) red. vi, If the participant lifts the correct finger(s), the corresponding cue(s) turn(s) green. vii, A trial is not validated until the response is fully correct, that is, without any red cue on the screen. viii, As soon as the trial is validated, the green finger(s) turn back to gray. ix, Participants need to reposition all fingers and press the buttons to start a new trial. C Different stimulus modes and clusters: the 15 possible modes are grouped into 6 clusters (1 F, 2F-Homo, 2F-Ipsi, 2F-Diag, 3 F, and 4 F) based on the number of fingers to be recruited (1, 2, 3, or 4) and the coupling/decoupling interactions involved. D Timing and general procedures of each trial. In the SRT run, the participants had to execute the same movement in runs of 10 consecutive trials (no choice required). In the CRT run, the trials were presented in a pseudo-randomized order, thus, participants had to execute a different movement on each trial (choice required).

Task description

Participants were instructed to place each finger on the corresponding button and press it (Fig. 7B) and only lift specific fingers of the left and/or right hand, as cued on the screen. Two white hands corresponding to the left and right hands were presented on a black background, and the middle and index fingers were presented in gray color. Each trial started with a 1500 ms interval during which participants were instructed to press all four fingers and keep them pressed, waiting for the cues. Upon pressing the proper button, the corresponding gray cues turned white. In case not all the keys were pressed during the aforementioned period, the trial was aborted. Once all four buttons were pressed simultaneously and the 1500-ms interval was over, a cue appeared after a random jitter of 400–500 ms. The purpose of this jitter was to avoid the prediction of cue presentation time by the participants. Subsequently, a subset of the finger cues appeared on the screen in which the to-be-moved fingers turned blue. In response to this stimulus, participants needed to release contact with the corresponding button(s) as quickly and as correctly as possible by lifting the cued finger(s). Upon lifting the correct finger(s), the corresponding cue(s) turned green, and upon lifting the wrong one(s), the corresponding cue(s) turned red. A trial was only validated when the response was fully correct (i.e., without any red cues on the screen) within 4800 ms from the start of the trial. Afterward, all the cues turned back to gray. Then, the participant repositioned all fingers and pressed the buttons to start a new trial. If the participants did not react within 4800 ms from the start of the trial, the trial was considered aborted. Reaction time was measured as the elapsed time from the appearance of the cue to the lifting of all of the cued fingers. Details of the trial procedure are presented in Fig. 7D.

All the 15 possible stimulus modes were tested: 4 single-finger conditions, 6 two-finger conditions, 4 three-finger conditions, and 1 four-finger condition (Fig. 7C). We merged these subtests to finally obtain a single measure per participant for SRT, CRT and NRT.

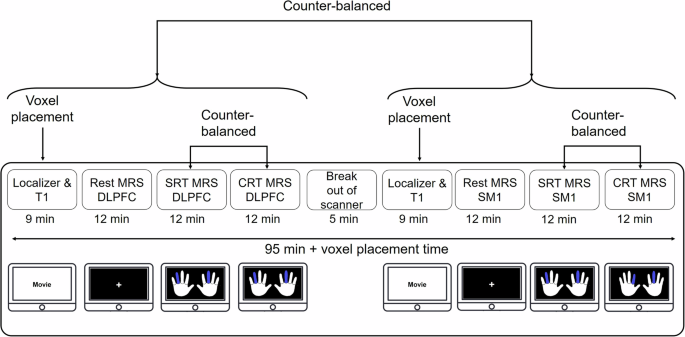

Experimental design

Participants followed a one-day, two-block program that was conducted in the MRI scanner, with a 5-minute break between the two blocks. Each block was composed of three sub-blocks, including a resting state sub-block, a simple reaction time (SRT) sub-block, and a choice reaction time (CRT) sub-block. During the resting state sub-block, participants were presented with a fixation cross on the screen and were instructed to stay relaxed and fixate on the fixation cross to eliminate eye movements. The SRT sub-block was composed of 10-trial runs of each of the 15 stimulus modes (150 trials). The stimulus modes were presented in a pseudo-randomized order. Before each run of the SRT, participants were presented with the figure that showed the cue for the next 10 consecutive trials (predictive: no choice required). The CRT sub-block also consisted of 150 trials (10 trials for each of the 15 stimulus modes). However, these trials were not presented as trial runs but were all presented in a pseudo-randomized order, this is, with a different cue on each trial (nonpredictive: choice required). The order of the SRT and CRT sub-blocks was counterbalanced across the participants in each age group. Accordingly, half of the participants performed SRT before CRT, while the reverse order was administered for the remaining participants. During each block, MRS data were acquired from one of the voxels of interest (VOI). Between the two blocks (one for each VOI) participants had a 5-minute break outside the scanner. To mitigate any potential effect of VOI scan order, a counterbalanced approach was implemented across participants in each age group. Consequently, for half of the participants, the MRS data were acquired from the SM1 VOI prior to the dlPFC VOI, while for the other half, the order was reversed (Fig. 8).

dlPFC: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, SM1: Sensorimotor cortex, SRT: simple reaction time, CRT: choice reaction time.

Behavioral data analysis

For error-free trials, the elapsed time between the onset of visual stimulus presentation and the time the participant released the corresponding fingers was obtained and defined as RT. Within each stimulus mode, trials with RT values more than 3 times scaled median absolute deviations67 were considered outliers and removed. This procedure resulted in removing 8.03 ± 1.38% of trials in YA and 7.59 ± 1% of trials in OA. The median value of the remaining trials in each stimulus mode was obtained and averaged.

To perform a comprehensive investigation of the behavioral data, the reaction times in the SRT, CRT, and the net RT (NRT) (index calculated by subtracting the SRT values from the CRT values), were reported: (a) SRT, as the representation of the motor component of action selection, (b) CRT, as the representation of the motor and the central processing components together, and (c) NRT, which provides a distinct measure of the central processing of action selection. Additionally, to assess motor learning for each component, we subtracted the reaction time in the second block from that of the first block for the SRT, CRT and NRT indices.

MR scanning

Neuroimaging data were acquired at the University Hospital Leuven using a 3 T Philips Achieva dStream MRI scanner equipped with a 32-channel receive-only head coil. For each participant, a high-resolution T1-weighted image was acquired using a chemical shift 3D turbo field echo (3DTFE; TE = 4.6 ms, TR = 9.7 ms, 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 voxel size, field of view (FOV) = 182 × 288 × 288 mm3, 182 sagittal slices, scan duration ~7 min) to capture the anatomical features of the brain. MRS data were acquired using the MEGA-PRESS sequence68,69 (TE = 68 ms, TR = 2 s, 2 kHz spectral width) using parameters similar to the previous studies of our group27,28,70. Notably, MRS requires the use of relatively large voxels to ensure an acceptable signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)71. Thus, considering the shape and dimensions of each region of interest, the voxel dimensions were set as 30 × 30 × 30 mm3 for the left SM1 and 40 × 25 × 25 mm3 for the left dlPFC voxel72. ON and OFF spectra were acquired in an interleaved fashion, corresponding to an editing pulse at 1.9 or 7.46 ppm, respectively. Prior to each MRS acquisition, an automatic shimming procedure was performed. For both VOIs, 16 unsuppressed water averages were acquired within the same VOI using identical acquisition parameters.

Because the edited MRS signal contains a significant contribution of macromolecules (GABA + macromolecules), the GABA measurement is usually referred to as a GABA+ measurement. However, for simplicity, we refer to it as GABA concentration. MRS VOIs were identified on a subject-to-subject basis using anatomical landmarks. The SM1 VOI was first placed over the hand knob of the left motor cortex. Afterward, it was rotated to stay parallel with the cortical surface in the coronal and sagittal plane73. For the dlPFC VOI, the center of the voxel was positioned in the axial slice above the superior margin of the lateral ventricles. In this slice, the VOI was placed at one-third of the anterior-to-posterior distance of the brain, centered in between the lateral and medial walls of each hemisphere74.

To obtain baseline levels of neurometabolites, MRS scans were collected during the resting state at the beginning of the scan session. Subsequently, the MRS data were acquired from the SM1 or dlPFC voxels during the performance of the SRT and CRT tasks. Subsequently, the participants rested for 5 minutes outside the scanner. Upon their return to the scanner, the same procedure was repeated to collect MRS scans from the remaining VOI (Fig. 8). The procedure was the same for both YA and OA groups.

MRS data analysis

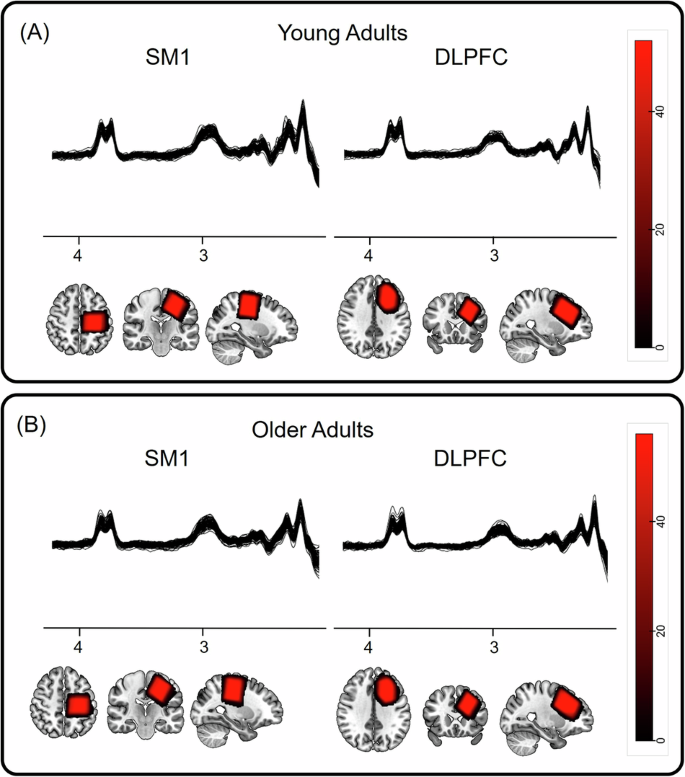

An overview of the acquired spectra at all three time points, as well as the overlap of the individual’s VOIs (transformed to MNI space), are presented in Fig. 9. The MRS data were analyzed using the Gannet analysis toolkit (version 3.3.1; https://markmikkelsen.github.io/Gannet-docs/)75. First, spectral registration was applied for frequency and phase correction76. Subsequently, the GABA and Glx signals were fitted between 4.2 and 2.8 ppm using a three-Gaussian function, and the water signal was fitted using a Gaussian–Lorentzian model. Next, considering that concentrations of GABA and Glx are negligible in CSF and assuming that they are twice as high in gray as compared to white matter, the concentrations were corrected for tissue fractions within each VOI77. To this end, MRS voxels were co-registered with the anatomical images that were used to position the VOIs correctly. The fractions of gray matter, white matter, and CSF within the VOIs were calculated by segmentation of the anatomical image using SPM12. In the last step, GABA and Glx concentrations were normalized to the average voxel composition of the whole group77. In agreement with previous work from our group and others27,29,70, water was used as the signal reference compound.

The MRS spectra obtained from the SM1 and dlPFC brain regions and the heatmap of the MRS VOI overlap across participants in standard MNI152 space (radiological view) in (A) young and (B) older adults.

The quality of the MRS data was assessed both qualitatively by visual inspection of the spectra for the presence of lipid contamination and quantitatively by inspecting the measures of SNR, frequency drift, and full-width half-maximum (FWHM). A detailed quantitative description of the quality of spectra can be found in Table S2. In addition, the spectra did not suffer from BOLD effects on the linewidth as a result of task performance, as indicated in Table S3.

To investigate the task-induced modulation in the neurometabolite concentrations, we calculated the change in metabolites according to three indices: a) the modulation during SRT, estimated by subtracting the resting state neurometabolite concentration from the neurometabolite concentration during the SRT; b) the modulation during CRT, estimated by subtracting the resting state neurometabolite concentration from the metabolite concentration during CRT; and c) the NRT modulation, estimated by subtracting the neurometabolite concentration during SRT from the metabolite concentration during CRT.

Statistical tests

Statistical analyses were carried out using R (version 4.1.2, R Core Team, 2021)78,79.

Behavioral data

In order to assess the effects of age (YA vs OA) and condition (SRT vs CRT), a mixed model ANOVA was conducted, with Condition as a within-subject factor and Group as a between-subjects factor. To control for the effect of order on behavioral measures (SRT and CRT) an ANOVA was performed.

Resting-state concentrations of neurometabolites

To investigate whether resting state levels of neurometabolites were different between VOIs and age groups, a 2 × 2 [Age group (Young vs Older adults) × VOI (SM1 and dlPFC)] repeated-measures ANOVA was designed, in which VOI was entered as a within-subject factor and “Age group” as a between-subject factor.

Modulation of neurometabolites

An ANOVA control analysis was performed to examine whether the order of measurement (according to the counterbalanced design) had an effect on the metabolites concentrations (Table S4). In addition, the descriptive statistics of baseline levels of GABA according to order and age group are presented in Table S5.

To investigate whether performing the tasks induced any significant changes in the concentration of neurometabolites and whether this effect was different between Age groups and VOIs, a 2 × 3 × 2 [Age group (Young vs Older adults) × Task (Resting state, during-SRT, and during-CRT) × VOI (SM1 vs dlPFC)] mixed-design ANOVA was conducted in which “VOI” and “Task” were within-subject factors and “Age group” was a between-subject factor.

Brain-behavior associations

We used multiple regression analyses to investigate the associations between concentrations of neurometabolites and behavioral measures. Therefore, separate multiple regression analyses were conducted to investigate different research questions. We employed a stepwise (backward) variable selection procedure, to identify the most predictive variables for inclusion in our regression models. To increase the interpretability of the results in the presence of interaction effects, the data were mean-centered before entering them in the multiple regression analyses

Predicting task performance based on task-induced modulations in the neurometabolite concentrations

We examined whether modulations in GABA and Glx in the SM1 and the dlPFC voxels during the SRT and CRT tasks (SRT and CRT modulation indices), and their interaction with age, were significant predictors of the respective behavioral index (SRT or CRT reaction times). In addition, we tested whether the NRT could be predicted by the NRT modulation in GABA and Glx in SM1 and dlPFC, and their interaction with age.

Predicting initial motor learning based on task-induced modulations in the neurometabolite concentrations

We estimated a motor learning index for SRT, CRT and NRT by subtracting the reaction times from block 2 (either SRT, CRT or estimated NRT) from reaction times in block 1. With this estimation, a higher index indicates an improvement in performance across time (reduction in reaction times). We explored whether these indices of motor learning capacity (for SRT, CRT and NRT) could be predicted by Age group, neurometabolite modulations in each VOI and/or their interaction.

For all statistical analyses, the level of significance was set at p < 0.05, two-sided. P-values of ANOVAs were corrected for sphericity using the Greenhouse-Geisser method when Mauchly’s test was significant. Partial eta squared (ƞp2) were reported to indicate small ( ≥ 0.01), medium ( ≥ 0.06), and large ( ≥ .14) effect sizes (Sink and Stroh, 2006).

Responses