Characterization of senescence and nuclear reorganization in aging gingival cells

Introdcution

Aging is characterized by the progressive decline in tissue and organ function over time, and this process also impairs gingival wound healing1. Degenerative and hyperplastic pathologies associated with aging are, at least in part, linked by a common biological mechanism: cellular senescence, a cellular stress response2. Cellular senescence plays a crucial role in regulating physiological and homeostatic processes, especially during embryonic development and wound healing. However, it can also become pathological, contributing to aging, various diseases, and metabolic disorders3.

Senescent cells (SnCs) were initially identified as a distinct form of stable cell cycle arrest that serves as a protective mechanism against cancer4. These cells exhibit notable morphological changes, such as acquiring a characteristic flattened and enlarged shape, increased senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-βGal) activity, reduced replicative capacity, and the expression of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). SASP is primarily marked by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the accumulation of transcriptionally inactive heterochromatic structures, known as senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF)5. SAHF contains several molecular markers, including hypoacetylated histones, histone H3 methylation at lysine 9 (H3K9me3), heterochromatin-associated protein 1 (HP1), and the histone variant macroH2A6. These heterochromatic structures repress the expression of genes that promote proliferation, thereby enforcing the cessation of the cell cycle6.

SnCs interact with their environment by secreting cytokines and growth factors. Through SASP, they initiate immune-mediated clearance by macrophages, NK cells, and T-cells. SASP is characterized by elevated levels of cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-6, MIF, IL-1α, and IL-1β, which function as pro-inflammatory mediators7. Additionally, chemokines like CXCL-1, CXCL-8, CXCL-5, and CXCL-4 act as neutrophil chemoattractants, while CCL-3, CCL-4, CXCL-12, and CCL-2 are key chemokines that regulate migration and infiltration of monocytes/macrophages8. CCL2 (monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, MCP-1) has been described as the primary chemokine responsible for monocyte recruitment in vivo9,10 and IL-8, CXCL-12, and CCL-3 attract T cells. Notably, CCL-2 and CCL-3 are also involved in attracting NK cells7.

Accumulating evidence suggests that SnCs build up in tissues as aging progresses, contributing to age-related pathologies11. While numerous instances of senescence have been observed at sites of age-related disease, it remains unclear whether these cells cause the disease or are simply a result of the pathology. In certain cases, the loss of proliferative capacity in competent cells may lead to conditions such as glaucoma, cataracts, diabetic pancreatic dysfunction, and osteoarthritis. Inflammation driven by SASP might play a causal role in diseases such as atherosclerosis, diabetic adipose tissue dysfunction, and cancer11. However, there is limited knowledge about the accumulation of SnCs in human gingival tissues during aging. The processes of chromatin rearrangement and SAHF formation during aging are poorly understood, as is the role of immune surveillance in monitoring cellular senescence during chronological aging. Moreover, it remains to be seen whether the accumulation of senescent cells during aging could contribute to the increased prevalence of oral diseases observed in older individuals.

Results

SnCs accumulate in human gingival tissue with chronological aging

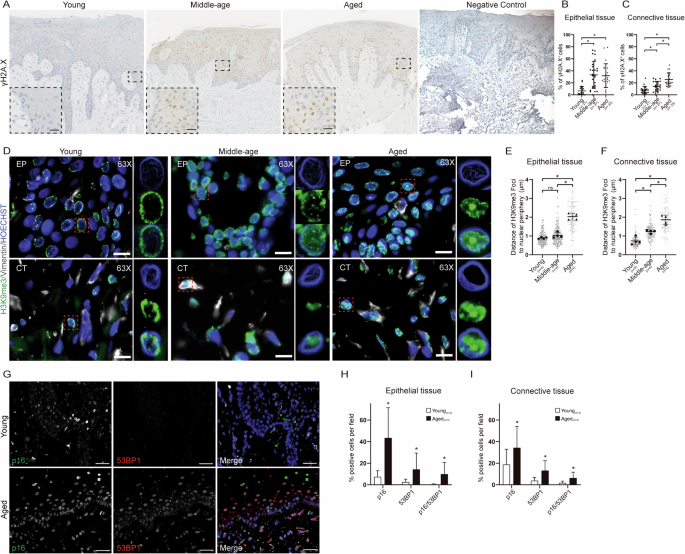

Persistent DNA damage is a key trigger of cellular senescence, identifiable by the presence of markers such as γH2A.X and 53BP112. In this study, we utilized γH2A.X as a marker to detect SnCs in healthy gingival samples ranging from 16 to 72 years of age. Our analysis revealed a significant increase in the number of SnCs in gingival samples from healthy aged donors compared to younger ones (Fig. 1A). Specifically, the percentage of SnCs in epithelial tissue increased from 6.6% ± 1.5 in the young to 31.9% ± 7.2 in the aged (Fig. 1B) and human gingival connective tissue increased from 7.9% ± 1.8 in young individuals to 25.5% ± 5.7 in older individuals (Fig. 1C). These findings are consistent with observations in other mammals, such as aged baboons, where approximately 15% of total fibroblasts in skin biopsies are senescent cells13, and in old mice, where an average of 10% senescent cells are found in organs such as the liver, pancreas, lung, and skin14.

A Immunohistochemistry of γH2AX in gingival tissue during aging. B Quantification of γH2A.X- positive cell in epithelial tissue. C Quantification of γH2A.X-positive cell in connective tissue (young n = 21, 15,616 cells; middle-age n = 27, 11,593 cells; aged n = 23, 17,723 cells). D Immunostaining in gingival tissue during aging for H3K9me3 (green), and nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). Magnification 63× and the inset of epithelial and connective tissue 63× (young n = 4, 194 cells; middle-age n = 4; 156 cells; aged n = 4, 113 cells). Scale bar 10 μm. E Quantification of distance of H3K9me3 foci to nuclear periphery in epithelial tissue (young n = 4, 194 cells, aged n = 4, 113 cells). F Quantification of the distance of H3K9me3 foci to the nuclear periphery in connective tissue (young n = 4, 100 cells, aged n = 4,100 cells). G Immunostaining in gingival tissue during aging for p16INK4a (green) and 53BP1 (red) and nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bar = 20 μm. H Quantification in epithelial tissue of p16ink4a positive cells, 53BP1 positive cells, and double-positive cells (young n = 3, 2319 cells; aged n = 3, 2576 cells). I Quantification in connective tissue of p16ink4a positive cells, 53BP1 positive cells and double positive cells (young n = 3, 1696 cells; aged n = 3, 748 cells). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences to the young group.

We also employed H3K9me3, a marker for heterochromatin enriched in senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF), to compare young and aged epithelial tissues. While both young and aged epithelial tissues expressed H3K9me3 (Fig. 1D), the distance of H3K9me3 foci from the nuclear periphery was significantly different between young and aged tissues. In young epithelial cells, the foci were closer to the nuclear periphery compared to aged epithelial cells (0.890 ± 0.024 µm versus 2.004 ± 0.059 µm) (Fig. 1E) and in connective cells the foci were closer to the nuclear periphery compared to aged epithelial cells 0.732 ± 0.033 versus 1.860 ± 0.055 (Fig. 1F). Additionally, we analyzed the expression of p16INK4a, a cell cycle regulator associated with aging and senescence and 53BP1. We observed an increase in p16INK4a expression during gingival aging (Fig. 1G). Graphs show the quantification of p16INK4a, 53BP1, and double-positive cells for both proteins in epithelial and connective tissue. We found that both aged healthy gingival epithelial and connective tissue exhibit significantly higher numbers of p16INK4a-positive cells, 53BP1-positive cells, and double-positive cells for p16INK4a and 53BP1 compared to young gingival tissue. There are more than sixfold increases in the epithelium and more than twofold increases in connective tissue compared to young gingiva (Fig. 1H, I).

Nuclear reorganization and senescence markers in HGF during aging

We examined the primary cells within connective tissue and identified distinct nuclear phenotypes in fibroblasts from six aged individuals compared to those from six younger individuals (Fig. 2A). Given the distinct nuclear phenotypes observed in Fig. 2A, we further evaluated nuclear morphology by measuring nuclear perimeter, area, and form factor15. Our analysis revealed a statistically significant increase in both the perimeter (Fig. 2B) and area of the nucleus in HGF from aged donors compared to young donors (Fig. 2C). Additionally, the form factor was significantly reduced in HGF from aged individuals, indicating a more lobulated nuclear shape (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, we observed an age-related increase in the number of nuclear invaginations, as detected by Lamin B1, within the nuclear interior (Fig. 2E, F). Also, statistical differences in Lamin B1 MFI were observed between fibroblasts from young and aged individuals showing average values of 5.070 from 3 young donors and 4.537 from 3 aged donors (Fig. 2G).

A Nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue) from HGF from six young donors and six aged donors Magnification 63×. Scale bar = 5 μm. B Quantification of nuclear area. C Quantification of nuclear perimeter. D Quantification of form factor (young n = 6, 1856 cells; aged n = 6, 1696 cells). E Representative images from an immunofluorescence of Lamin B1 from HGF young donor fibroblast (18 years old) and a nucleus in an aged fibroblast (60 years old). F Quantification of nuclear Lamin B1 invaginations (young n = 4, 122 cells; aged n = 4, 129 cells. G Quantification MFI of Lamin B1 (young n = 4, 99 cells; aged n = 4, 111 cells). H Quantification of positive cells for SA-βGal of HGF from 6 young and 6 aged individuals. I Immunofluorescence of γH2A.X and Hoechst from nucleus from young and aged donor fibroblast. J Quantification of 0 foci, 1–3 foci and over 4 foci of γH2A.X. K Immunofluorescence of 53BP1 and Hoechst from nucleus from young and aged donor fibroblast. L Quantification of over 3 foci of 53BP1 young n = 6, 264 cells; aged n = 6, 200 cells. M Immunofluorescence of pP38 from young and aged donor fibroblast. N Quantification of pP38 normalized by nuclear area in HGF from young and aged donors (young n = 5, 263 cells; aged n = 5, 177 cells). O Deming regression of pP38 (Y180/Y182) and Form factor showing x-intercept of 0.893 versus 0.821 p ≤ 0.0001, and similar slope p = 0.9754. P ROC curve with area under the curve for pP38 (Y180/Y182) and Form factor (young n = 5, 263 cells; aged n = 5, 177 cells). All assays were performed in quadruplicate. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences.

To assess the presence of SnCs in HGF across different age groups, we analyzed SA-β-Gal activity (Fig. 2H) and the expression of γH2A.X (Fig. 2I, J), and 53BP1 from over 3 foci (Fig. 2K, L). Quantification of γH2A.X-positive cells showed significant differences between HGF from young and aged individuals in 0 foci and more than 4 foci (Fig. 2J). Additionally, a quantification of over 3 foci of 53BP1 revealed statistical differences between the young and aged HGF populations (Fig. 2I).

p38 is a subfamily of MAPKs involved in stress-activated protein kinases, which play a critical role in various cellular processes16. p38 also plays a crucial role in cellular senescence and the regulation of the SASP17. Our analysis of phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) in HGF demonstrated an age-associated increase, with a higher number of p38 foci in aged fibroblasts (Fig. 2M, N).

Deming regression analysis between phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) and form factor revealed that a decrease in form factor was associated with increased p38 phosphorylation (Fig. 2N). Although the slopes were similar, the x-intercepts differed: 0.893 versus 0.821. This suggests that, although aged cells had higher baseline p38 phosphorylation, the rate of increase remained the same with changes in cell area and perimeter. Combining p-p38 foci with form factor as a predictor of aging yielded a positive predictive power of 79.3% and a negative predictive power of 74.2%, with an AUC of 0.83 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.7864–0.8739; p ≤ 0.0001; Tjur’s R2 of 0.304, Hosmer–Lemeshow p = 0.0034) (Fig. 2O).

Detection of Lysotracker presence in PBMCs and HGF during aging

Our data indicate that SnCs accumulate in human gingival tissue as individuals age (Fig. 1). To investigate the underlying mechanisms, we conducted a co-culture experiment involving PBMCs, which include lymphocytes (T and B cells), natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells and monocytes with HGF. PBMCs from young individuals were pre-incubated with LysoTracker, a dye that stains lysosomal granules such as acidic granules perforin and granzymes—key components of the cytotoxic process responsible for eliminating SnCs. We obtained an average of 35.88% of positive LysoTracker in our young PBMCs (MFI over 0.7605), where it has been described that 30% of T cells are cytotoxic and between 5 and 15% are NK cells18,19. These pre-treated PBMCs were then co-cultured with HGF from both young and aged donors for four hours. The 4 hour timepoint was empirically chosen because no major cell lysis occurred yet. By immunofluorescence imaging, we quantified the number of cells positive for 53BP1 and LysoTracker. We found a lower number of double positive HGF in the co-culture assays using fibroblasts from aged donors compared to those from young donors (44.4% versus 17.4%) (Fig. 3A, B), suggesting a reduced transfer of LysoTracker from PBMCs to fibroblasts from aged donors.

A Immunofluorescence from a co-culture of 4 h of HGF from young and aged individuals with young PBMCs loaded with LysoTracker and using anti 53BP1. Arrowheads indicates PMBC. B Quantification of the percentage of double positive 53BP1/LysoTracker cells (young n = 3, 109 cells; aged n = 3, 140 cells. C immunoblot of lysate from HGF of young and aged individuals using anti CD112, MICA/B and as a control β-Tubulin. D Quantification of relative expression of CD112 (n = 5). E Quantification of relative expression of MICA/B (n = 5). F Immunostaining in gingival tissue during aging for MICA/B (green), CD112 (red) and Hoechst (blue) (young n = 3, aged n = 3) scale 20 μm. G Proteome profiler from conditioned media from HGF from young and aged individuals. H Quantification of pixel intensity of the proteome profiler array (n = 4).

We further evaluated the expression by western blot of two major ligands for the NK cell-activating receptor, MHC class I-chain-related protein A (MICA), an activator of the natural killer receptor NKG2D, and CD112 (Nectin-2), a ligand for DNAM-1, both of which play roles in the immunosurveillance of abnormal cells20. Western blot analysis revealed that gingival fibroblasts from young donors exhibited higher levels of these ligands compared to fibroblasts from aged donors (Fig. 3C–E). This observation, along with the increase in senescent cell percentage, suggests a decline in the expression of ligands that activate NK cells, such as MICA/B and CD112, in aged fibroblasts that correlate with the decrease observed in the presence of Lysotracker in HGF transferred from PBMCs (Fig. 3A, B). Additionally, we analyzed the expression of MICA/B and CD112 in gingival tissue by immunohistochemistry, showing expression the CD112 mainly in the connective tissue and not in the epithelial tissue (Fig. 3F).

Next, we analyzed the secretome using a cytokine proteome profiler array on 24-h conditioned media from HGF of both young and aged donors. The results showed decreased levels of CCL2, IL-6, and CXCL2, but increased levels of IL-8 in fibroblasts from aged donors compared to those from young donors. This suggests that the ability of fibroblasts to attract immune cells may vary with age, potentially influencing the immune response and the clearance of SnCs (Fig. 3G, H).

Immune recruitment by SnCs in HGF from young and aged individuals

To quantify the recruitment of PBMCs by SnCs, HGF were co cultured in a ratio 1:10 of PBMCs for 4 h. By immunofluorescence we evaluate the senescence using 53BP1 and Hoechst to stain DNA for cell types. We quantify the numbers of PBMCs closeness of 15 μm of positive 53BP1 HGF (Fig. 4A, B).

A Immunofluorescence of 53BP1 and Hoechst from a co-culture of 4 h of HGF from young and aged individuals with PBMCs (young n = 4, 109 cells; aged n = 4, 140 cells) from four independent experiments using the same PBMC donors for young and aged HGF. B Quantification of PBMC recruited to over 3 foci of 53BP1 positive cell. C Frames from Single-cell recruitment measurements by time-lapse for 60 min. Arrowheads indicates PMBC closeness to 15 μm, dashed line delimited perimeter. D Quantification of the arrival of the first immune cells to a senescent HGF (first recruitment time) (young n = 3, 10 cells; aged n = 3, 10 cells). Statistical differences from Mann–Whitney test. E Quantification of kinetics priming in minutes (young n = 3, 10 cells; aged n = 3, 10 cells). Statistical differences from Mann–Whitney test. F Representative Graph of tracking number of recruited cells by a senescent HGF from young and aged donor. G Graph from 20 videos of recruited PBMCs (young n = 3, 10 cells; aged n = 3, 10 cells). Statistical differences from two-way ANOVA (p = 0.0001). Scale bar = 10 μm.

To analyze different parameters of the recruitment of PBMCs by senescent cells, we conducted time-lapse imaging over 60 min, focusing on senescent fibroblasts incubated with PBMCs. The PBMCs were pre-labeled with Hoechst dye, and senescent HGF were detected using CellEvent Senescence Green. After one hour of imaging and individual cell recruitment counts, we analyzed the data, marking PBMCs recruitment events by SnCs along the time axis (Fig. 4C). Our findings indicated that senescent cells from young donors recruited PBMCs more rapidly and in greater numbers than those from aged donors (Fig. 4B). We also measured the time to the first recruitment event (t1), defined as the interval between the start of the experiment and the first recruitment of a PBMC by a SnCs. SnCs from young donors-initiated recruitment 6.83 times faster than those from aged donors (Fig. 4D).

Additionally, we assessed the kinetic priming, or the time interval between successive recruitment events. We observed that SnCs from young individuals had a much shorter interval between recruitments (2.49 min) compared to SnCs from aged donors (9.90 min) (Fig. 4E). Finally, we quantified the overall kinetics of recruitment by recording the number of PBMCs recruited by SnCs over time, showing quantification of PBMCs recruited by time in one representative video for each condition (HGF from 18 years old and 73 years old) (Fig. 4F) and as supplementary figure, we incorporated the video of this representative graph showing the first frame the presence of CellEvent and then the blue channel to evaluate PBMC recruitment (Supplementary Video 1), and providing a time-resolved analysis of recruitment in both young and aged senescent HGF from 20 independent experiments (Fig. 4G).

Discussion

Cellular senescence is often regarded as a “guardian” of tissue homeostasis, acting as a mechanism to eliminate damaged cells through the immune system. In this study, we observed the accumulation of SnCs during gingival aging, characterized by increased levels of γH2A.X, 53BP1 and p16INK4a, as well as a greater distance of H3K9me3 from the nuclear periphery, suggestive of SAHF formation. Furthermore, HGF from older individuals exhibited larger nuclear areas and perimeters, heightened DNA damage responses, increased activation of p38, and a reduced capacity to recruit immune cells. This was accompanied by the modulation of the ligands MICA/B and CD112.

The percentage of SnCs in gingival tissue during aging observed in Fig. 1 are in strong agreement with previous research by Chandra et al. 21, which showed that heterochromatin in growing WI-38 cells is located at the nuclear periphery, while in senescent WI-38 cells, there is a loss of Lamin-dependent local interactions in heterochromatin. Also, it suggests that it is important to study middle-aged subjects during the early manifestations of tissue changes associated with aging, where we had the most dispersion of data. This data is according to nonlinear dynamics during aging using PBMCs22.

Previous studies have characterized the senescence induction in HGF23 and human periodontal ligament cells (HPDL)24, but these studies have mainly focused on replicative senescence models. In our research, we aimed to use HGF from different age ranges to assess senescence as a parallel model of study that reflects what happens in human aged gingival tissue, where we reported an increased accumulation of senescent cells. Consistent with our findings, Ikegami et al. 24 and Rattanaprukskul et al. 25 also report an increase in the abundance of p16-positive cells in aged gingiva in murine and human models, respectively.

Previous studies have shown that the accumulation of senescent osteocytes exacerbates inflammation in aged mice26. Our findings also revealed more nuclear envelope invaginations in fibroblasts from aged donors compared to those from younger donors, indicating potential genomic reorganization during aging. Similar nuclear changes have been observed in premature aging models, such as cells from patients with Nestor-Guillermo Progeria Syndrome (NGPS), where an increased number of invaginations was reported27.

The host’s innate and adaptive immune surveillance systems, including macrophages, NK cells, and T cells, can eliminate SnCs. In the context of vascular leukocyte trafficking, firm adhesion is typically guided by CCL2 and CCL5, as well as by CXC motif chemokines such as CXCL1, CXCL4, and CXCL528. Interestingly, our data showed decreased levels of CCL2 in the conditioned media from aged fibroblasts, correlating with their reduced recruitment capacity. However, it has been reported that systemic CCL2 levels increase with age29. Additionally, factors secreted by senescent cells, such as IL-8, GROα, IL-6, and IGFBP-7, can reinforce the senescent phenotype, potentially exacerbating cellular senescence during aging. Our data indicated that conditioned media from HGF of aged donors contained higher levels of IL-8 compared to that from younger donors, which aligns with the observed accumulation of senescent cells during aging. Interestingly, in line with our findings, IL-8 mRNA expression was found to be elevated in older donors compared to younger donors in human gingival samples25. Notably, IL-8 mediates the inflammatory response by attracting neutrophils, basophils, and T cells30, although neutrophils and basophils were not part of the PBMCs used in our study. Further experiments will be necessary to quantify neutrophil recruitment.

Immune surveillance of damaged, infected, or transformed cells is primarily mediated by NK cells and lymphocytes through the activation of NKG2D and DNAM-1 stimulatory receptors20,31. While much of the research on SnCs clearance has focused on NKG2D receptor activation via ULBP and MIC family ligands32 or HLA-E33, tumor cell elimination involves activation of both NKG2D and DNAM-1 receptor axes. Our study found that senescent HGF from aged donors significantly recruit slowly and fewer PMBC compared to SnCs from young donors, as demonstrated by time-lapse analysis of co-cultures (Fig. 4) and also presents a decrease in relative levels of CD112 and MICA/B (Fig. 3). This may represent a novel mechanism of immune evasion by senescent cells. Moreover, our findings suggest a correlation between double-stranded DNA damage, ATR activation, and Nectin-2 expression on the cell surface, as previously observed in tumor models20. In senescent gingival fibroblasts from aged donors, we observed an increased number of 53BP1 foci, active p38 foci, nuclear morphological changes, and reduced Nectin-2 expression compared to senescent fibroblasts from younger donors. Consequently, these SnCs exhibited decreased transfer of Lysotracker by immune cells.

This relationship may highlight a potential mechanism for the accumulation of senescent cells with aging and could be considered a target for interventions aimed at enhancing the successful elimination of these cells, thereby mitigating the detrimental effects associated with cellular senescence.

The clearance of SnCs by the host immune system has been reported in models of malignant transformation, where SASP factors secreted by senescent tumor cells stimulate the proliferation of surrounding cancer cells34. Additionally, the elimination of p16INK4a-positive senescent cells has been shown to delay age-related disorders in tissues such as the kidney, heart, and adipose tissue35. Future studies should explore how the removal of senescent cells in aged gingival tissue could reduce sterile inflammation and potentially prevent the development of periodontal disease.

Materials and methods

Explants were obtained from healthy gingiva surrounding third molars or during crown lengthening surgery. Periodontal examination demonstrated sites with probing depth <4 mm, no loss of attachment and no bleeding on probing. Tissues were obtained from 82 individuals with no severe underlying diseases and classified as young (15–25 years old), middle age (30–48 years old) and aged (50–73 years old), with the informed consent of the patients29. The Ethical Committee, Universidad de Chile approved the protocol (002-2022) for tissue obtainment. Patients did not report preexisting medical or drug histories in the last 6 months and no smokers were included1. All experiments were performed using Human Gingival Fibroblast (HGF) expanded between passages three and eight. (n = 26 young, n = 30 middle-age, and n = 26 aged). HGF were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone Laboratories Inc., Logan, UT) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 as described in Caceres et al.1. For each set of experiments, we used at least HGF from different three donors not pooled. Furthermore, the study was conformed to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Immunohistochemistry

The tissue samples were rinsed in PBS and fixed in 4% w/v fresh paraformaldehyde pH 7.4 for 24 h, then subsequently dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Then 3 μm sections were treated according to Villalobos et al.36. The samples were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-phospho histone H2A.X (Ser139) (Millipore #05-636) for chromogenic stained or Histone H3 Trimethyl Lys 9 (Novusbio #6F12-H4) 1/100, 53BP1 (Novusbio #NB100-304), Nectin-2/CD112 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology #sc-373715) 1/50, MICA/B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology #sc-137242) 1/50, p16 (Invitrogen #MA5-17142) 1/100, for immunofluorescence stained (IHC-F). For negative control sections, primary antibody was replaced by blocking solution. After three washes for 10 min each, primary antibodies were detected by incubation in anti-mouse/rabbit IgG RTU biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA, catalog #BP-1400) for 30 min at room temperature. Secondary antibody labeling was amplified using the ABC Peroxidase Standard Staining Kit (Thermo Scientific catalog #32020) for 30 min at room temperature. After three washes with PBS, the immunolabeling signal was detected with DAB Peroxidase substrate (Vector Laboratories catalog #SK-4100). Mayer’s hemalum solution (Merck catalog #109249) was used for nuclear counterstaining. Images were acquired using a Nanozoomer -XR digital slide scanner C12000 (Hamamatsu Photonics KK, Hammamatu City, Japan).

For IHC-F, the primary antibodies were detected by incubation in an anti-secondary isotype-specific conjugate with Alexa Fluor at room temperature. Then, sections were treated according to Villalobos et al.36.

Immunofluorescence

HGF from young or aged individuals were plated on 12 mm coverslip, fixed in fixative solution [4% w/v formaldehyde (freshly prepared from paraformaldehyde, Sigma-Aldrich catalog #158127) in DPBS, pH 7.4, cells were blocked with blocking solution containing 4% w/v nonfat dry milk in DPBS, 0.1%Triton X100 during one hour, and incubated with respective primary antibody incubated with either anti-phospho histone H2A.X (Ser139) (Millipore #05-636) 1/500, or 1/500, 53BP1 (Novusbio #NB100-304), phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) (R&D#MAB8691) 1/500, Lamin B1 (Invitrogen #PA5-19468) 1/500.

Detection of senescence associated beta-galactosidase (SA-βGal)

HGF from young and aged individuals were washed in PBS and fixed with 2% w/v paraformaldehyde and 0.2% v/v glutaraldehyde for 5 min. Then, the cells were processed according to Fernandez et al.37.

Immunoblot

Gingival fibroblasts were lysed followed by size fractionation on SDS–PAGE, transferred and 2 h or overnight incubation with primary antibodies: Anti-Human MICA/B (RyD Systems catalog #MAB13001) [1/1000], Anti-Human Nectin-2/CD112 (RyD Systems catalog #MAB2229) [1/1000], and Anti-beta Tubulin (Thermo Fisher Scientific catalog #PA5-16863) [1/5000]. After 3 washes with 0.1% v/vTweeen-20/TBS, the membranes were incubated with the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h. After 3 washes for 10 minutes each with 0.1% v/v Tween-20/TBS, immunoblots were visualized by Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific catalog #34080). The images were acquired with a MiniHD9 imager (Uvitec Ltd., Cambridge, UK) and quantified using the Nine-Alliance software (Uvitec Ltd.).

Cytokine array

Conditioned media from 24 h cultured young HGF and aged HGF were analyzed using Proteome profiler human cytokine array kit (R&D systems #ARY005B) according to manufacture protocol29.

Co-culture of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with human gingival fibroblasts (HGF) and recruitment assay

PBMCs were isolated from 5 mL of fresh blood from young donors (18–25 years old) through Ficoll-Paque (Cytiva #17544202) density gradient centrifugation, according to manufacture protocol, obtaining an average of 1.5 × 106 PBMCs per mL of blood. For the co-culture assay, 10,000 HGF from young and aged donors seeded onto fibronectin-coated surfaces (5 μg/mL) were incubated with PBMCs at a ratio of 1:10 in-serum-free DMEM at 37 °C for 4 h with 5% CO2. Prior to co-culture, PBMCs were treated with 200 nM LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Invitrogen #L7528) for one hour, then washed three times with PBS and stained with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific #62249) 1/5000 for 5 min. Co-cultured cells were washed once with PBS and fixed for immunofluorescence to detect 53BP1. We quantified double-positive HGF for 53BP1 with more than three nuclear foci and LysoTracker over 0.843 ± 0.148 MFI. Each co-culture assay was conducted using the same PBMCs donor against HGFs from young and aged individuals.

To perform the recruitment assay, HGFs from young and aged were treated with the CellEvent Senescence Green Detection Kit (Invitrogen #C10851) for 30 min and stained with Hoechst for 5 min. Then, PBMCs previously stained with Hoechst, as was already described, were added to the HGFs at a ratio of 1:10 in 50 μL of serum-free DMEM. Imaging was conducted using an AxioObserver 7 microscope equipped with a motorized stage and a Neofluar 20×/0.5 objective. We analyzed over one hour of imaging with time-lapse recordings captured every 5 s to determine the initial recruitment time (t1 min) of PBMCs to SnCs within a 15 μm proximity. The kinetics of priming were assessed by calculating the time required for the second cell to arrive (in minutes)38. The location and timing of recruitment events were manually identified.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least four times, using HGF from different donors on separate occasions. Data are presented as means ± SD and were analyzed for statistically significant differences using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test (for non-parametrical data distribution), and ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test for more than two group comparisons. To assess the association between variables and account for potential errors in variable distribution, a Deming regression analysis was performed on the quantitative results. Finally, a multiple logistic regression analysis was performed using form factor and the number of p-p38 foci as independent quantitative variables, with aging treated as a dichotomized outcome variable. Discrimination of aging was analyzed with Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and described using the area under the curve (AUC) with a 95% confidence interval (CI)39. Sensitivity and specificity for aging discrimination were also reported. In all analyses, a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data was analyzed using the GraphPad Prism software, version 10.1 (La Jolla, CA, USA).

Responses