The role of Mediterranean diet in cancer incidence and mortality in the older adults

Introduction

Mediterranean diet (MD) is a dietary pattern inherently linked with the populations surrounding the Mediterranean Sea area. It is characterized by a high intake of vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts and whole grains, a moderate intake of poultry, fish, alcohol (mostly as red wine), and a low intake of red and processed meat, with olive oil as the primary fat source1. Mounting evidence suggests that greater adherence to MD is associated with reduced incidence of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), mental disorders, and cancer2,3,4,5. These anticancer properties have been linked to the anti-inflammatory and antilipidemic effects attributed to the MD’s composition, including an abundance of dietary phytochemicals and fibers6. According to the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF), high consumption of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low intake of red and processed meat might lower cancer risk.

Although the relationship between MD and cancer has been explored in several studies in recent years, scant attention has been paid to its implications for older adults. This gap in the literature is significant, considering the global demographic trends towards greater longevity and the corresponding rise in cancer prevalence among older adults. As the population ages, there is an associated need for effective strategies in this specific population, considering that cancer is the second leading cause of death globally7. It is estimated that over 90% of cancers are attributable to modifiable risk factors and suboptimal diet is responsible for about 5–10% of total cancer cases8. Integrating dietary and lifestyle modifications to reduce cancer risk and mortality in subjects at increased risk is mandatory and a variety of approaches and efforts will have to be devoted to promote proper lifestyles and dietary habits9,10.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to comprehensively assess the impact of adherence to the Mediterranean diet as a potential strategy against cancer risk and mortality within the older population, assessing whether higher adherence to MD correlates with a decreased incidence of cancer and with lower cancer-related mortality.

Results

Study selection and exclusion process

Overall, 1169 records were identified from database searching and after duplicates removal, 783 records were screened with title and abstract. 207 reports were assessed for eligibility by full text and, in the end, 17 reports from 17 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review and 16 in the meta-analysis. Full detailed retrieval process is presented in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1).

CENTRAL Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. n number.

The list of studies excluded by full text is available in Table S2. Notably, the majority of reports (n = 144) were excluded because the corresponding study included patients younger than 60 years old and a subgroup analysis for older patients was not available. Many of these reports (n = 104) were published after 2015. Median age was 59 years (IQR 52.5–62); 119 did not report an age cut-off while 24 reported a cut-off different from 60 years (without a corresponding analysis). Most reports included more than one cancer (n = 26), followed by breast (n = 22), colorectal (n = 18) and prostate cancer (n = 13). The main characteristics of reports excluded for this reason are reported in Table S3.

Studies characteristics

The main characteristics of included trials are presented in Table 1. In detail, of the 16 studies included, one was a phase III randomized clinical trial (RCT)11 and the other 15 were non randomized studies of intervention (NRSIs), respectively seven cohort studies and nine case control studies10,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. The total number of older adults included was not available, due to missing data from three studies20,21,24. Considering the available data, the number of older subjects was 25789. Fourteen studies reported outcomes for cancer incidence (one RCT and 13 NRSIs, of which five cohort studies and eight case-cohort studies). Three NRSIs reported outcomes for cancer mortality (one case-control study and two cohort studies). The mediterranean diet score (MDS) was used by 11 of the included NRSIs to evaluate MD adherence, while the other five used alternative scores like MEDILITE (one), rMED (one), aMED (two), aMEDr (one). The main differences between scores were related to a different evaluation on alcohol consumption and fatty intake6,27,28. Eleven studies evaluated MD adherence considering per one-point increase (OPI) in the scores (nine for incidence and two for mortality) and for five studies MD adherence was categorised by quantiles (four for incidence and one for mortality). Two studies (one for incidence and one for mortality) compared MD to other dietary patterns. Four studies evaluated gastrointestinal cancers (two gastric, one pancreatic cancer and one hepatocellular carcinoma). Two studies were focused on breast cancer, four on genitourinary cancers (two for bladder, one for prostate) and one on endometrial cancer. A study considered head and neck and one lung cancer. Five studies included only older populations, while data for other studies came from subgroup analyses. One study was included in the systematic review but not in the meta-analysis due to missing data.

Cancer incidence analysis

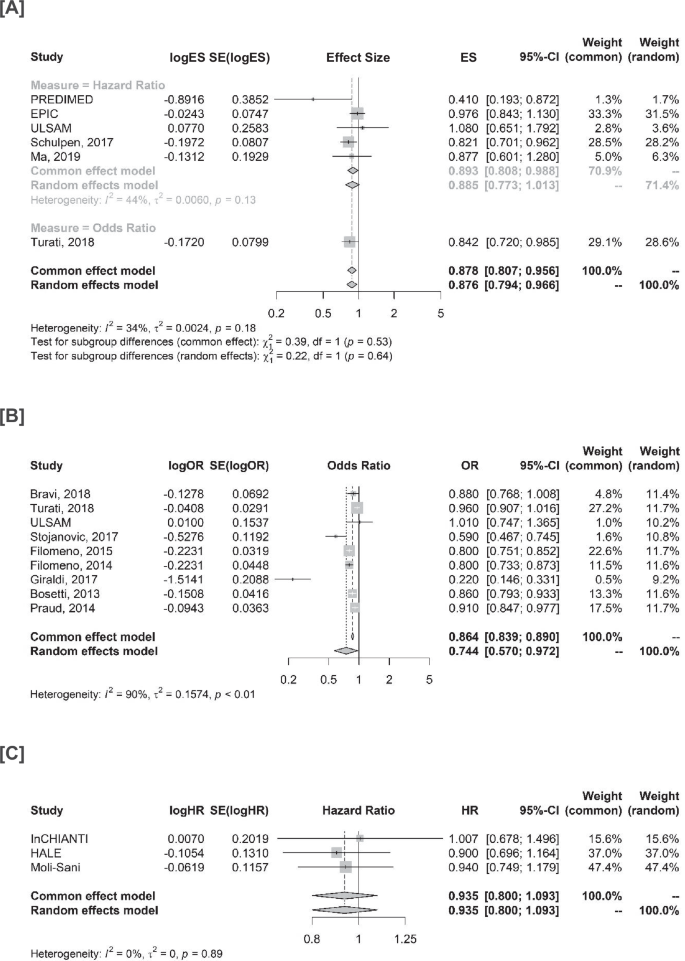

Pooled results from medium and high adherence are reported in Fig. S1. Regarding cancer incidence, the pooled hazard ratio (HR) for studies evaluating incidence as a time-to-event endpoint and considering adherence as quantiles was 0.885 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.773–1.013, I2 = 44%) (Fig. 2A). Results were consistent in our sensitivity analysis excluding the PREDIMED trial, which was the only RCT that randomized participants to MD without considering adherence (pooled HR 0.906, 95% CI 0.797–1.031) (Fig. S2A). In the exploratory combined analysis including also odd ratios (ORs), the pooled effect size was 0.876 (95% CI 0.794–0.966, I2 = 34%), suggesting a reduction in the incidence of cancer of 12%. Consistent results were observed in studies evaluating ORs as a OPI in cancer incidence (pooled OR 0.744, 95% CI 0.570–0.972, I2 = 90%) (Fig. 2B). Results were also consistent in our sensitivity analysis excluding the paper from Giraldi and colleagues (OR 0.851, 95% CI 0.786–0.920, I2 = 80%) (Fig. S3B).

A Studies evaluating cancer incidence and MD as categories. B Studies evaluating cancer incidence and MD as one-point increase. C Studies evaluating cancer mortality and MD as categories. ES effect size, SE standard error, CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, OR odds ratio.

Cancer mortality analysis

In terms of cancer mortality in older adults, our results did not indicate a clear protective effect, with a pooled HR of 0.935 (95% CI: 0.800–1.093, I2 = 0%) (Fig. 2C). Similar results were observed in the sensitivity analysis excluding the HALE trial (HR 0.956, 95% CI 0.785–1.164, I2 = 0%) (Fig. S2B).

Subgroup analyses

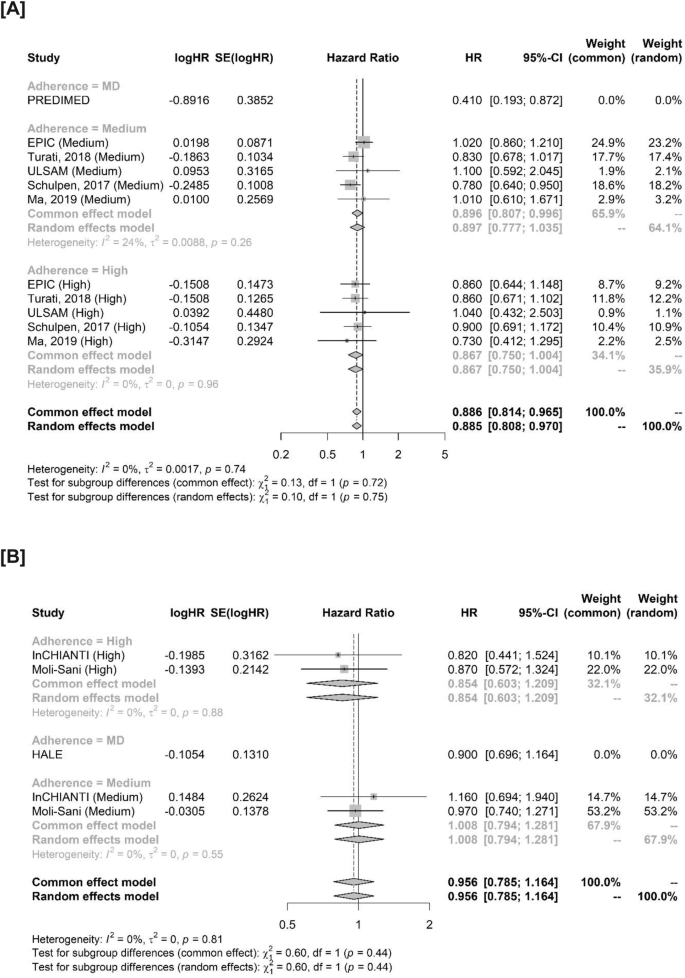

In our subgroup analysis for cancer and MD adherence, in terms of HRs no significant interaction (p = 0.75) was observed between subjects with medium adherence (HR 0.897, 95% CI 0.777–1.035) compared to those with high adherence (HR 0.867, 95% CI 0.750–1.004) (Figs. 3A and S4). As the assumption of linearity could not be confirmed, no discretization of OPI estimates was performed. In terms of cancer mortality, the pooled HR for medium adherence was 1.008 (95% CI 0.794–1.281), compared to 0.854 (95% CI 0.603–1.209), with no significant interaction (p = 0.44) (Fig. 3B). In all studies reporting HRs, MDS was available: therefore, no subgroup analyses were performed. No significant interaction was observed for ORs (p = 0.18) in terms of the score used: however, MEDILITE was used only in one study and results in the subgroup including only MDS were consistent with the primary analysis (OR 0.763, 95% CI 0.566–1.029) (Fig. S3A). Consistent results were also observed after removing the study by Giraldi et al. (OR 0.872, 0.820–0.928) (Fig. S3B). No significant interaction was found between case-control and cohort studies (p = 0.11) (Fig. S3C).

A Studies evaluating MD adherence for cancer incidence. B Studies evaluating MD adherence for cancer mortality. Studies not considering adherence (PREDIMED and HALE) are reported in the forest plot but were excluded from this analysis. HR hazard ratio, SE standard error, CI confidence interval, MD mediterranean diet.

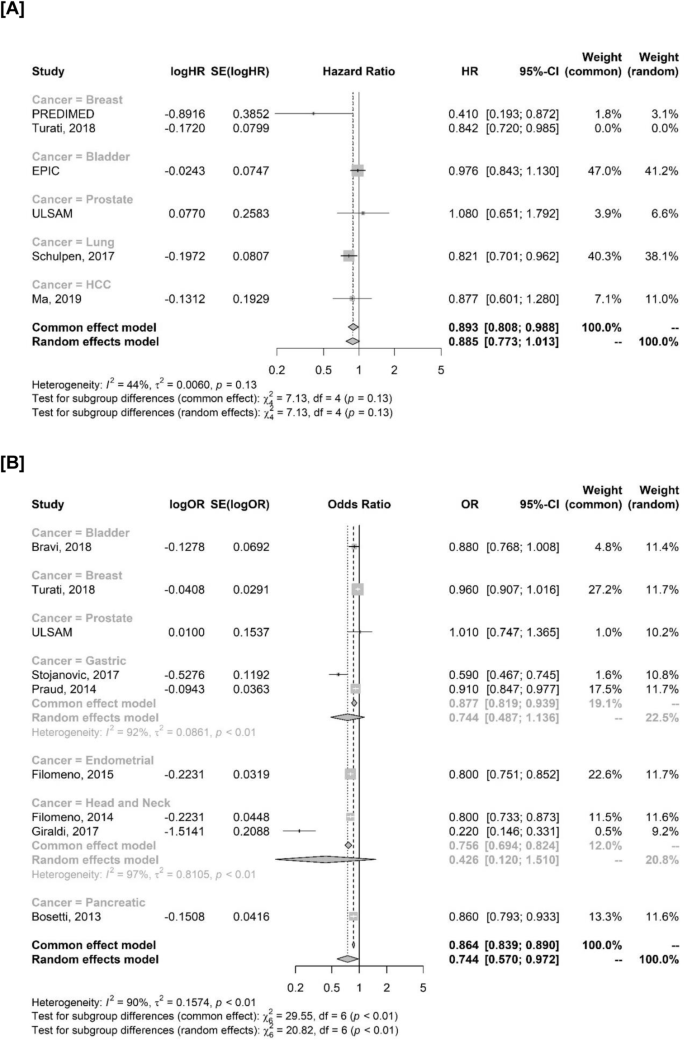

According to cancer type, no clear interaction was observed in terms of HR (p = 0.13). Breast cancer (HR 0.410, 95% CI 0.193–0.872) and lung cancer (0.821, 95% CI 0.701–0.962) reported the lowest HRs (Fig. 4A). A significant interaction was observed for ORs in OPI (p = 0.002), suggesting a potential differential effect according to cancer type. In detail, gastric (random effects model; OR 0.744, 95% CI 0.487–1.136), endometrial (OR 0.800, 95% CI 0.751–0.852), pancreatic (OR 0.860, 95% CI 0.793–0.933) and head and neck cancers (random effects model; OR 0.426, 95% CI 0.120–1.510) seemed to benefit the most from MD (Fig. 4B). Results were consistent in sensitivity analyses including only studies evaluating MD as OPI using MDS and after outlier removal (Fig S5A-B).

A Cancer incidence in studies evaluating HRs. The study by Turati et al., 2018 is reported but not included in the analysis since it evaluated ORs. B Cancer incidence in studies evaluating MD as OPI. OPI one-point increase. OR odds ratio, HR hazard ratio, SE standard error, CI confidence interval.

Quality assessment and risk of bias

In cohort studies, significant concern comes from the selection item (especially for ascertainment of exposure, and determination of the absence of the outcome of interest at baseline), as well as the outcome item (adequacy of the follow-up). Specifically, in some studies, the ascertainment of the exposure was not based on secure records. Additionally, in many studies, it was not possible to conclusively exclude that patients already had cancer at the time of enrollment. Moreover, not all subjects completed follow-up, with the possibility of attrition bias. In case-control studies, main sources of bias were found in the selection item (adequate case definition, selection and definition of controls) and outcome (ascertainment of exposure). In detail, potential sources of selection bias cannot be excluded, and ascertainment of exposure was generally not blinded and based on medical records. The only RCT included was considered as overall high risk of bias, as the results are based on few cases and came from a secondary analysis of a previous trial. The detailed risk of bias assessment is reported in Fig. S6.

According to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) scoring system, the global quality of evidence should be considered low both for cancer incidence and mortality. The main reasons for downgrading were risk of bias, indirectness, and imprecision. Sources of heterogeneity came from the different study designs, different tumors evaluated and different scores used in the assessment of MD adherence. The details are reported in Table S4.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis analysed current evidence to shed light on the association between the Mediterranean diet and cancer risk and mortality in older adults. Our results suggest that MD could play a role in the prevention of cancer incidence, with no apparent effect on cancer mortality. There was no sufficient evidence to indicate a differential impact of adherence in older subjects, while differential effect on different cancer types was confirmed.

Results of our analysis align with previous literature findings on the inverse association between the MD and cancer risk in the general population. MD has been reported to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease2,3, overall mortality2,10,29,30, and to play a favourable role in various cancers as well31,32,33,34,35. Findings from a recent meta-analysis regarding MD and cancer in the general population showed that MD might lower risk of colorectal, head and neck, respiratory, gastric, liver and bladder cancer and was inversely associated with mortality in the general population, and all-cause mortality among cancer survivors: no association was seen between adherence to MD and cancer mortality risk36. As in our analysis, one of the limitations stated by the authors was the low or very low certainty of evidence. Notably, consistently with our results, adherence to high-quality nutritional patterns, such as the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) or the alternate HEI was associated with approximately 15% reduction of the cancer risk37.

Some findings confirm that MD could also be inversely associated with cancer progression and aggressiveness in older patients, especially for prostate cancer (PC)38,39. In older prostate cancer patients (≥65 years) undergoing active surveillance, Gregg and colleagues38 reported an inverse association between MD adherence (assessed with MDs, categorized in tertiles as low, medium or high) and PC progression, with an HR of 0.86 (0.73–1.02). Similarly, the “Prostate cancer project” (PcaP) was an observational study that compared MD (assessed with the MDS) and the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH, assessed with the DASH score)39. In the older subgroup (≥65 years), high MD adherence showed an inverse association with PC aggressiveness, with an age-related effect: a moderate vs low adherence showed an OR of 0.70 (95% CI 0.47–1.04) and a high vs low adherence showed an OR of 0.43 (95% CI 0.25–0.75). The results of that study suggested that MD may reduce the odds of highly aggressive prostate cancer. This could be explained by two main hypotheses: first, dietary benefits that derive from MD may accumulate over time, and second, the effect of MD may be magnified as the risk of aggressive prostate cancer increases with age.

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the protective effect of MD on cancer risk. Considering its high content of flavonoids, omega-three fatty acids, and folic acid, MD can play a role in the inflammaging, hindering subclinical inflammation and thus slowing and retarding of cell senescence: these molecules interact synergistically in beneficially affecting several metabolic pathways, including the glycaemic control40. Moreover, there is evidence that MD anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties can impact telomere length: a recent meta-analysis found an association between MD adherence and shortening, which is associated with biological aging41.

In addition, mounting evidence confirms the inverse association between MD adherence and obesity, a known risk factor for some hormone-sensitive neoplasia: this is related to body weight reduction and to reduced risk of gaining weight over time with adherence to MD42.

In our subgroup analysis, when evaluating MD adherence, our findings do not suggest any differences between high or medium adherence in terms of cancer risk reduction. While these results should be taken with caution and considered only hypothesis-generating, they raise suggestion that in older age even small dietary changes can have an impact, so that strict adherence to nutritional regimes should not need to be chased at any cost. Notably, a differential effect emerged according to tumour type, and as expected, head and neck and gastrointestinal cancer seemed to achieve the most significant benefit from MD.

As growing attention is being paid to older subjects for anticancer treatments43, future and ongoing studies should concentrate on modifiable risk factors in terms of cancer prevention and survival outcomes in this population, hopefully with dedicated analyses. In general, our findings highlight how older population is often unrepresented or neglected in most studies: the majority of studies investigating the role of MD in subjects with or without cancer were excluded from our systematic review due to the absence of a dedicated age subgroup analysis. While this exclusion was necessary to maintain the focus on the older population, it resulted in a substantial reduction in the number of studies included in the meta-analysis. This study-level limitation, which inevitably translates into a limitation of our work due to the potential loss of information, results in an overall low quality of the evidence and underscores the important gap between the total number of studies and the absence of dedicated analysis for older adults. This is a matter of concern: while there is a need for dedicated RCTs both for MD and older adults, the attention paid to this specific population should be raised even in observational studies. Moreover, even if challenging, specific analyses need to be conducted distinctly considering “oldest old” subjects (≥85 years). It should be noted that defining a threshold for older age can be challenging, as chronological age alone may not adequately capture the concept of an “older subject”, which also depends on biological factors and functional impairments contributing to aging process. In this study, an age cut-off of 60 years was selected to balance biological relevance with the availability of current evidence. However, alternative age thresholds, such as 65 or 70 years, may be appropriate in different contexts and could be considered in future research.

While the lack of benefit observed in terms of cancer mortality could be due to the low number of studies included for this specific outcome (n = 3), this result was not unexpected. Whereas cancer remains one of the leading causes of death, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases become the main mortality determinants with the increase of age44. Age-specific cancers, such as prostate and breast cancer, due to therapeutic advantages, tend to have longer overall survivals, which can result in “dying with cancer” rather than “dying from cancer.” This unavoidably reduces the magnitude of the benefits of interventions, making it challenging to evaluate the effect of the MD without competing risk analyses. Although competing risk analysis is notoriously difficult to conduct, efforts should be made to integrate it into study designs to properly evaluate the interaction between MD, cancer and other age-related diseases. Additionally, the assessment of time-to-event outcomes requires studies with long follow-up periods to capture long-term effects. While overall survival and cancer mortality are traditionally prioritized as “hard” endpoints, in older populations other outcomes such as quality of life and functional status should also be considered.

Our study certainly carries some limitations. First, our analysis is based on study-level data, as individual patients’ data was unavailable. Consequently, the exact number of included subjects was unavailable due to missing data from three studies. While the total number of older adults was not specified in these studies, the corresponding measures of effect were available for inclusion in our analyses. Therefore, we conducted the analysis only for ORs and HRs, without considering absolute risk differences. We expect this missing data to primarily impact the knowledge of the total number of included subjects without significantly affecting the overall conclusions, as the uncertainty in the measurements is accounted for within the CIs and the corresponding standard errors (SEs). Furthermore, due to the low number of studies included for each of the three primary analyses, a formal assessment of publication bias was not possible. Most included studies were NRSIs, and only one was an RCT, with a prevalence of case-control studies. Therefore, our results are based on observational rather than experimental data, limiting the certainty of evidence regarding the causality relationship. While being a limitation, this reflects the current scenario: conducting RCTs in older patients is challenging for the evaluation of dietary patterns as it is for pharmacological interventions. While one of the main reasons can be found in the inability to maintain participants’ compliance during the long-term follow-up, older adults have specific issues to consider: several age-related changes (edentulism or dysphagia) can lead to changes in dietary habits and mitigate the effect of nutritional patterns. Moreover, age-related changes in metabolism and para-physiological hyporexia are something to consider since they can reduce the impact of MD45. Cognitive impairment, such as memory loss or dementia, can significantly hinder an older adult’s ability to remember dietary instructions or recognize the importance of following a specific diet. Dementia and cognitive impairment can also lead to recall-bias, especially when subjects have to complete a food frequency questionnaire. Physical limitations, including mobility issues or conditions like arthritis and social disability, including impairments in daily living activities, can lead to a loss of nutritional autonomy making food preparation and eating itself difficult, leading to reliance on caregivers.

Most included studies were heterogeneous in their design, and different scores for assessing MD adherence were used. While our sensitivity analyses showed consistency in the results, this reflects the need for standardization of MD assessment and reporting. Another point to consider is the lack of information about the quality of consumed alimentary products (treated or not with chemical agents, hormones, antibiotics, etc.), as the food transformation processes could modify the attended benefits of MD. This implies that results could be biased due to the presence of harmful substances, which are risk factors for cancer onset. Although MD recommends a low intake of meat, this could have a harmful impact on human health as it could be rich in hormones such as oestradiol (known class A1 carcinogen), progesterone (class 2B carcinogen), androgens (class 2 A carcinogens), and antibiotics that contribute increasing antibiotics resistance and might alter gut microbiota increasing cancer risk, especially for colorectal cancer46,47. As expected, the studies included were conducted among European countries. Even if some of them were conducted among northern Europe countries (such as the Netherlands), which are not considered MD culturally based countries, this hinders the generalizability of results. Despite such limitations, our analysis still retains a meaningful and updated level of evidence in older population.

In conclusion, results from our meta-analysis suggest a potential protective role of MD in cancer prevention in the older populations. The low number of included studies and the low certainty of evidence of this work considering the GRADE approach impose caution in the interpretation of our findings. While an age-differential effect in the magnitude of benefit cannot be excluded, our results are in line with current literature in the general population, supporting the implementation of MD as a healthy nutritional regimen in older adults. No apparent effect was observed in terms of cancer-related mortality, reflecting the difficulties in improving this outcome by dietary modifications in older patients. In the end, our work raises attention on the need for dedicated studies in the older adults, and highlights how efforts should be made in ongoing studies to evaluate the complex interaction between age and dietary habits.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews (MECIR) standards and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement. Study protocol was registered in the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), registration number CRD42024481152.

Search strategy and selection criteria

A literature search was conducted in PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Embase to look for studies published from database inception to March 08th, 2024. No language restrictions were applied in the selection process and non-English studies were considered if they met the inclusion criteria. We searched for terms regarding the Mediterranean diet (“Mediterranean diet”, both as a Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] term and as a keyword), cancer (such as Neoplasms [MeSH Terms] and “cancer”) and older adults (such as “Aged” [MeSH Terms], “elderly”, “older” or “geriatric”). The full search strategy for each database, detailing search terms and boolean operators, is reported in Table S1. Three investigators (GG, LM and RT) independently searched and identified relevant studies. Disagreements were resolved through consensus or referring to a fourth investigator (GFC). Selected studies and meta-analyses or reviews were also searched through the reference section for other potentially eligible reports.

Phase II-III RCTs and NRSIs, including observational cohort and case-control studies, were considered eligible if the study population was focused on or included older adults in a subgroup analysis. The age cut-off for inclusion was set at ≥60 years. No restrictions on cancer type were applied. Mediterranean diet was considered as reported by the authors, including studies evaluating MD versus other dietary patterns and studies assessing MD adherence (considered as categorical—low/medium/high—or continuous as a OPI in adherence scores). Details on how adherence was categorized are reported in Table 1. When available, the MDS was considered the reference score, but no restrictions were applied to studies reporting other scores. Studies reporting at least one between cancer incidence and cancer mortality were deemed eligible. Case reports, retrospectives, single-arm trials, reviews, meta-analyses and editorials were excluded.

Data analysis and data extraction

Data about the following information were extracted: title and trial/study name, first author, publication year, study design, total number of participants and of older subjects enrolled (where available), cancer type, cancer incidence and cancer mortality (ORs and HRs with respective 95% confidence intervals, CIs) and adherence to the MD (according to the score as assessed by the authors). If several reports from a single study were available, the most complete and updated report was considered. Missing data about the older population of included studies were requested to the corresponding authors via email (GFC). In the end, the analysis was based only on already available published data. Missing data were not imputed: when data on the outcome were missing, the study was not included in the corresponding analysis.

Primary outcomes were cancer incidence and cancer mortality. Cancer incidence was the number of newly diagnosed cases per population at risk over a time period, defined as cases/population or cases/person-years (HR and OR). Mortality endpoint was cancer-specific mortality reported as time-to-event outcome (HR). When reported, results from adjusted multivariable analyses were considered. Three authors (GG, LM, and RT) independently extracted the data from included studies. Divergences were resolved through discussion or referring to another author (GFC).

Statistical analysis

Using data from published reports, we extracted ORs for dichotomous outcomes and HRs for time-to-event outcomes, along with their respective 95% CIs. These values were then converted into their natural logarithms and the corresponding SEs were calculated. Inconsistency between studies was assessed with Cochran’s Q while Higgins I2 index was used to quantify heterogeneity. Pooled estimates were calculated using a random-effects model, which was a priori assumed to better account for study differences in design and score used. The SE for ORs and HRs was calculated and interpreted as an estimate of variance to weight each study. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. Pooled estimates of HRs and ORs with 95% CIs were calculated with the inverse variance method, using the restricted maximum-likelihood estimator for τ2 and the Q-profile method for τ and its CI. Regarding cancer incidence, quantiles comparisons and OPI comparisons were considered separately. Low adherence was used as the reference treatment and compared to medium/high adherence. If separate results were reported in a study, the estimates were grouped together using a fixed effect model before conducting the main analysis. ORs and HRs for cancer incidence were initially considered separately and then an exploratory analysis was conducted by pooling HRs and ORs, to provide a comprehensive estimate of treatment effect and allowing inclusion of a wider range of studies. This approach is particularly justified when event rates are low since both measures describe the likelihood of an event comparing two groups. Randomized controlled trials and NRSI were considered together for the primary analysis; we then conducted sensitivity analyses excluding RCTs and studies evaluating MD vs other dietary patterns. Subgroup analyses were performed according to MD adherence, MD score used and specific cancer to account.

Risk of bias, quality assessment and publication bias

The risk of bias for RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool (ROB 2.0) and the Newcastle Ottawa scale (NOS) for NRSIs. The risk of bias was assessed for each one of the specific domains of each tool and overall risk of bias was then attributed to each study. Three authors (GG, LM, and RT) performed the initial assessment, disagreements were resolved through consensus or referring to a fourth author (GFC). The quality of evidence was evaluated using the GRADE approach. The following items were evaluated to provide the overall certainty of evidence: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness and imprecision. Due to the low number of included studies (fewer than ten) in each of three main analyses (cancer incidence as categories, cancer incidence as a OPI and cancer mortality), a formal assessment of publication bias was not performed for any of the outcomes.

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.2 (package ‘meta’). All tests were two-tailed and statistical significance was set at p-value < 0.05.

The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and was final in deciding whether to submit it for publication.

Responses