Decoding senescence of aging single cells at the nexus of biomaterials, microfluidics, and spatial omics

Introduction

Advances in medicine and healthcare have enabled humans to live longer, with most people living past the age of 60. The World Health Organization estimates that by 2030, one in six people alive will be over the age of 601. However, medicine and healthcare have yet to address the problems that occur with advanced age, such as cataracts, hearing loss, dementia, cardiovascular issues, and other geriatric syndromes. More worrisome, several diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, osteoarthritis, and cancer, increase in prevalence as people age1. Similarly, aging brings about changes in the immune system, and this impacts the body’s ability to fight foreign pathogens2. Thus, there is a critical need for understanding the mechanisms underlying aging at a cellular level and how these changes play a role in disease progression.

To establish the biological fingerprints of aging, it is important to distinguish biological measurements of aging from the conventional chronological age. While chronological aging is the conventional method for communicating a person’s age, it fails to account for individual factors: individual’s genetics and lifestyle choices1,3. Additionally, chronological age fails to capture an individual’s functional abilities and susceptibility to age-related diseases. Rather, a more functional metric to assess age is to look at either physiological age or biological age4,5. Physiological age refers to a functional decline in capacity or health state and is harder to delineate6. On a similar note, biological age refers to an accumulation of changes in cells and tissues over time and has been shown to be related to health outcomes7,8. However, while several established aging biomarkers have been studied, there is no definitive method for measuring biological age.9

Cellular senescence

Part of general biological aging is cells undergoing senescence, the process of cell cycle arrest that does not allow cells to divide and grow, to become senescent cells. Senescent cells are part of several natural, healthy biological processes, such as embryonic development, regeneration, cell fate reprogramming, wound healing, and tumor suppression10,11,12,13,14,15. However, senescent cells are postulated to play a role in aging and disease progression, particularly age-related diseases16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Thus, measuring senescence and senescent cells is necessary as a part of evaluating biological age34,35,36,37,38.

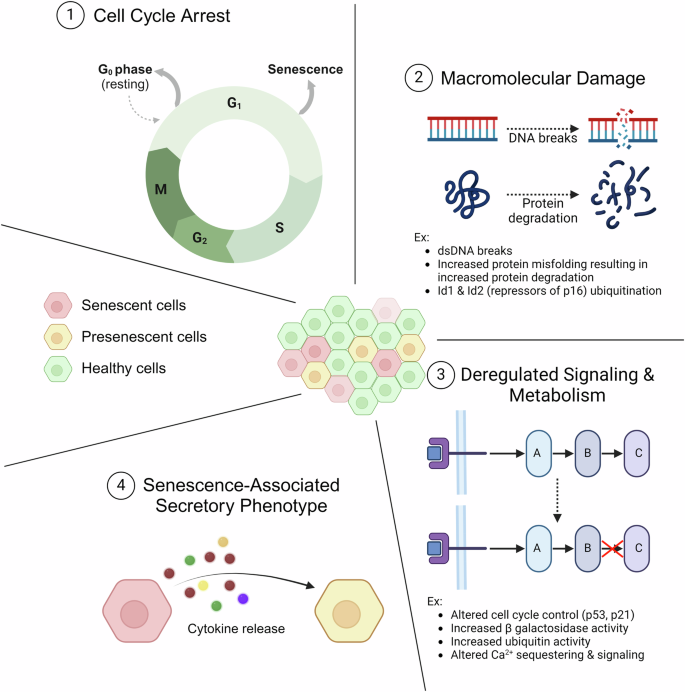

While the defining characteristic of cellular senescence is the cessation of cell division, other characteristics of these cells are macromolecular damage, dysregulated signaling and metabolism, and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), a new age-associated definition of cell types secreting signaling molecules to the tissue environment (Fig. 1)10,39. The macromolecular damage mostly occurs in double-stranded DNA breaks and protein denaturation as a result of misfolded proteins40,41,42,43. In addition, protein degradation can impact cell signaling pathways, such as in the case of the degradation of Id1 and Id2, known repressors of p1644. Additionally, both macromolecular damage and dysregulated signaling & metabolism contribute to cell cycle cessation, as they are part of the regulation methods used by cells when transitioning between cell cycle phases. Other examples of altered signaling and metabolism include increased β galactosidase activity, increased ubiquitination activity, and altered calcium sequestering & sequencing45,46,47,48. Furthermore, the idea of “presenescent” cells has also been discussed, with those cells distinguished from senescent cells via differences in gene expression, cell functionality, and ability to recover “normal” phenotypes49,50,51.

1 Senescence is most aptly defined by the cells’ exiting the normal cell cycle. Unlike cells entering a quiescent state (G0), senescence is characterized by an inability to reenter the normal cell cycle. 2 Another characteristic of senescent cells is macromolecular damage, notably double-stranded breaks in DNA and degradation of proteins. 3 A third characteristic of senescent cells is deregulated signaling and metabolism. Both deregulated signaling & metabolism and macromolecular damage contribute to cell cycle cessation, as they are part of the regulation methods used by cells when transitioning between cell cycle phases. 4 The final noted characteristic is the senescence-associated secretory phenotype, which results in a shift in the secretory profile of the cells. The cells release cytokines and other compounds that are intended to result in immune activation but can also lead to secondary senescence, where nearby cells are converted to senescent cells. Created with Biorender.com.

SASP—senescence-associated secretory phenotype

Of note, SASP factors released include inflammatory and stromal regulators52. These allow for senescent cells to communicate with and alter nearby cells with various effects. One of these effects is that neighboring cells are altered via paracrine signaling to become senescent cells as well53,54. Nearby stromal cells are modified which results in altered organ architecture & infrastructure55,56,57. The extracellular matrix is changed which causes alteration in the properties of the cellular microenvironment58,59. Another effect is that SASP results in immune cell activation60.

The first of these effects results in the exacerbation of the senescence state and the correspondence of morphological changes. The second effect is another example of the morphological changes but at the level of the tissue/organ rather than a specific cluster of cells. However, the next two effects point to specific ideas that can be exploited as avenues for designing experiments to understand and treat cellular senescence and, thus, some age-related ailments.

The third noted effect is the alteration of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and cellular microenvironment. Some examples of changes include increased crosslinking, increased fragmentation (caused by proteolysis), rearranged fiber alignment, and protein aggregation61,62. The effect of these changes is altered stiffness and altered viscoelastic properties (storage & loss modulus, viscosity, etc.)61,63,64. These changes influence cellular mechanotransduction and promote a divergence from the normal cellular state (normal meaning cells in the context of a “healthy” extracellular matrix). While conventional approaches suggest that a simple alteration of the extracellular matrix to a healthier state can restore natural cell function, cells demonstrate “mechanical memory.” This idea, mechanical memory, has been studied for a while and is used to describe the phenomenon of cells behaving as if in a prior microenvironment when introduced into a new one65,66,67. Thus, it is crucial to establish a biological mechanism by which aging alters the extracellular matrix, which in turn, causes major changes in cells.

Immune activation from cellular senescence

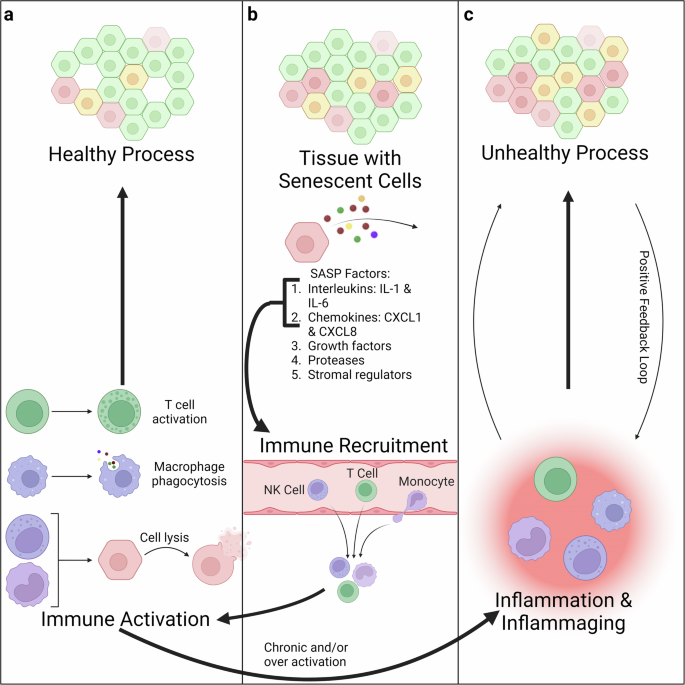

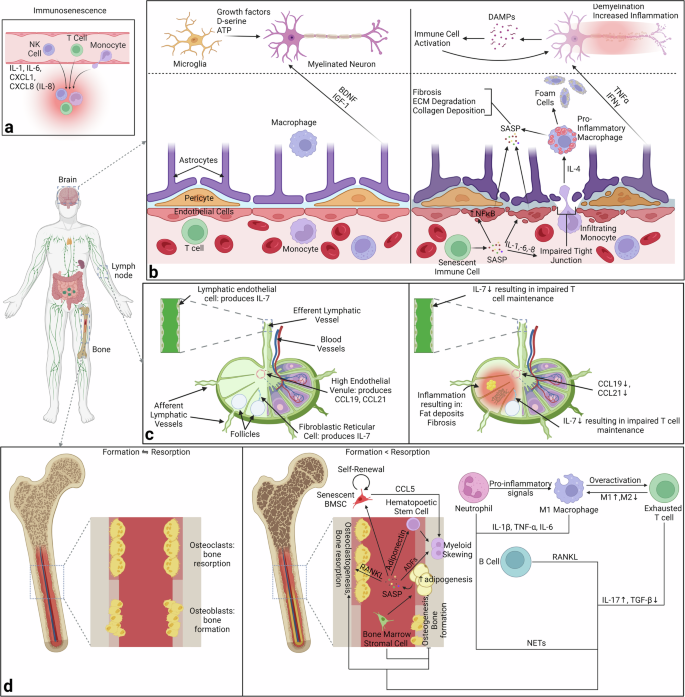

Another important effect of cellular senescence is the activation of immune cells. This phenomenon is one of the natural mechanisms the body uses to identify senescent cells and can slow the progression of age-related diseases (Fig. 2a)13,14,68,69,70. However, it can also result in aberrant immune cell response and overactivation of the immune system, leading to chronic inflammation71,72,73. This is an example of “inflammaging,” a broad term for the interplay between immune cells and inflammation that underlies several aging processes (Fig. 2b)74,75,76. In particular, inflammaging is characterized by persistent infiltration by immune cells (primarily from the innate immune system) and elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines75,77. Inflammaging can result in further “reprogramming” of these immune cells, exacerbating this cycle and creating a positive feedback loop (Fig. 2c)76,78,79. Thus, inflammaging is another biological pathway to understand better and to figure out its role in aging and the progression of age-related diseases.

a One of the biological bases for having cells adopt a senescent state is to create a distinct secretory profile that can recruit immune cells. In the healthy process, this results in immune activation and killing of the senescent cells. b Among the SASP factors, there are interleukins and chemokines which recruit the immune system to the tissue with senescent cells. c However, in the unhealthy process, this immune activation can become chronic or over-activated, resulting in inflammation and inflammaging. In this process, the inflammation results in further senescence, which results in further inflammation thereby forming a positive feedback loop. Created with Biorender.com.

In addition to inflammaging, several other changes occur in the immune system as a part of aging, collectively termed immunosenescence. Immunosenescence can also be defined as the progressive decline in immune function as a person ages and is characterized by a variety of changes75,80,81. There is altered signaling, particularly with the T-cell receptor and B-cell receptor82. This includes an altered response to damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)83. Anatomically, the thymus undergoes involution, where functional thymus tissue is replaced with adipose tissue84,85. This results in a lower number of naïve T cells and decreased T-cell receptor diversity86. Furthermore, the drop in naïve T cells results in a higher proportion of memory T-cells, contributing to increased immune activation87.

Most notably, there are changes to several different types of immune cells as a part of immunosenescence75,76. Neutrophils have a reduced response to chemotactic signals88. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells have a delayed and altered stimulation response89. Monocytes skew away from classical monocytes (CD14 + + CD16-)90. Dendritic cells have impaired recruitment91. Natural Killer cells have longer lifespans92. Finally, B & T cells can be senescent93,94.

B & T cell senescence is of particular note, as they are the two main lymphocytes and are involved in the adaptive immune response, particularly the creation of targeted antibodies. More work has been done establishing T cell senescence. In particular, it has been shown that T cell senescence can be characterized by some loss of both innate and adaptive immunity and a depletion of both naïve and effector T cells95,96. In the presence of infections or diseases like cancer, T cell senescence can result in T cell exhaustion95,97. Additionally, it has been shown that T cells can undergo replicative senescence (“natural” aging senescence) but also demonstrate premature senescence. The main mechanism for premature senescence is signaling from Treg cells to other T cells (effector, CD4, and CD8)98.

At the cellular level, pathway alterations and specific biomarkers have been identified in aged T cells. CD28 is among the most noted T cell markers, as it is necessary for T cell activation by antigens, as well as a costimulatory molecule for memory T cells99,100,101,102. While CD28- T cells are characteristic of T cell exhaustion, it has been shown that CD28- T cells can still proliferate in certain conditions and therefore are not senescent103,104,105,106. Other changes must also occur. One such change is the threshold calibration of the T-cell receptor (TCR). One of the central controllers of this process is miR-181a, which is a microRNA that controls the expression of several phosphatases that are part of modulating the TCR response threshold107,108. While the loss of miRNA-181a is initially useful to control autoimmune response, it eventually devolves into lower responses to antigens. In addition to this T-cell-specific change, other more general changes also occur, such as mitochondrial ROS leakage, DNA damage, increased homeostatic cytokines, and altered JAK-STAT pathway signaling97,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116. These changes could also contribute to T cell senescence.

As previously noted, there is less work published about B cell senescence. Prior work has established a specific subset of B cells called late memory B cells (LM B cells) that are characterized as IgD- and CD27- and are more prevalent in elderly populations117,118,119. These cells are more prone to senescence, as demonstrated by their high expression of p16INK4, a known senescence marker120,121. Also, it has been shown that IL-7 can induce senescence in B cells122. Finally, it has been shown that aging is associated with a decline in B cell lymphopoiesis123. One known mechanism for this is through the production of TNFα from aged B cells since TNFα suppresses new B cell formation124.

The biological changes brought about by cellular senescence and immunosenescence demonstrate a need for an approach that combines 3 distinct fields: biomaterials to modulate the extracellular microenvironment in accordance with the modifications brought about by aging, microfluidics to assess the kinetics of cellular senescence, particularly SASP, in vitro, and spatial omics to find markers indicative of the various biological pathways in tissues underlying these phenomena.

Biomaterials dissect the dynamics of aged and young cells

Typical experimental designs, involving cell culture, often overlook cellular aging and its impact on the extracellular matrix74. Biological aging involves substantial changes in the extracellular matrix, such as thinning of the basement membrane due to increased matrix metalloprotease activity, increased fibronectin synthesis, increased degradation, increased enzyme activity, altered glycosylation, and inflammation, which are all associated with the presence of senescent cells74. These changes result in altered mechanotransduction, causing cellular functional and morphological changes. These modifications are especially important when considering that cells possess a “mechanical memory” regarding their previous microenvironment, underscoring the importance of replicating this dynamic feature.

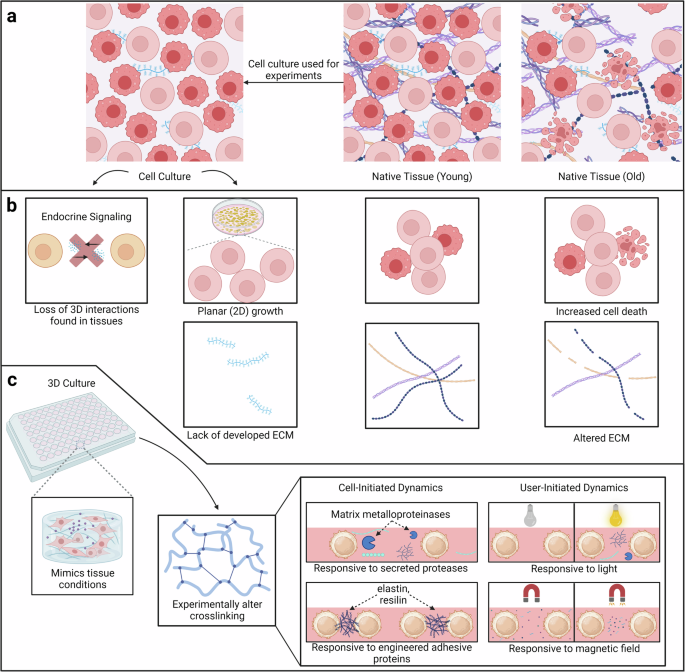

Another significant drawback of conventional experimentation, particularly in cell culture systems, is the lack of tissue complexity. These systems typically involve isolated cells growing in a two-dimensional (2D) environment, which fails to capture the three-dimensional (3D) interactions and architecture found in original tissue samples (Fig. 3a)74,125,126. This limitation can lead to results that do not accurately represent the physiological and structural aspects of tissues in the human body. This, consequently, can hinder our understanding of complex biological processes, including cell-cell interactions, signaling, and aging.

a In comparison to native tissue, cell culture lacks 3D interactions. These interactions are crucial when studying aging and senescence. b In particular, cell culture lacks endocrine signaling, layered growth, and developed extracellular matrix compared to native tissue. Additionally, there is a change in the composition of the extracellular matrix and microenvironment as age increases. Two notable changes are increased cell death and altered ECM. c Responsive biomaterials are a good alternative to cell culture, as they allow for 3D interactions while also being able to model both young and old extracellular microenvironments. There are two major classes of responsive biomaterials, both of which modulate their mechanical properties via altering crosslinking. Cell-initiated biomaterials respond to cellular stimuli such as secreted proteases or ECM components. In this case, the biomaterials often have peptide-based crosslinkers. The other class is user-initiated biomaterials, and there are two subtypes: light and magnetic field responsive. Created with Biorender.com.

One more significant drawback of conventional experimentation is the difference in the microenvironment compared to the natural environment in the human body125. Cells in their native microenvironment typically receive signals from neighboring cells (paracrine signaling), the extracellular matrix, and various soluble factors (Fig. 3b)127. In vitro culture may still have some preserved paracrine signaling, but it is harder to mimic endocrine signaling from other tissues with the soluble factors introduced via the media. Given that these signals are slower processes but lasting longer, they are a critical part of understanding tissue dynamics128.

Additionally, cell culture protocol generally dictates constant detachment and reattachment during passages. This means that the extracellular matrix (ECM) does not have time to form properly and influence cells’ characteristics129. This results in a lack of organ architecture compounding the issue highlighted in the prior paragraph. Such discontinuities can have implications for research related to aging that is strongly influenced by the interactions with the local microenvironment and extracellular matrix74,130.

Altogether, the ECM undergoes drastic dysregulation over time and communicates this with the cells; this change must be mimicked experimentally. It has been shown that altered stiffness can result in increased senescent cells, and senescent cells respond to altered mechanical cues from the extracellular microenvironment131. Given that biomaterials can be synthesized to have tunable mechanical properties that mimic the dynamism of native tissue, biomaterials provide an avenue for understanding the mechanical memory and aging of cells. Biomaterials can be inherently dynamic or have tunable properties74. Specifically, there are 2 broad groups of biomaterials: cell-responsive biomaterials (inherently dynamic) that respond to cellular stimuli and user-initiated biomaterials (tunable) that respond to user-initiated stimuli (Fig. 3c).

Cell-responsive biomaterials

Cell-responsive biomaterials, often referred to as inherently dynamic biomaterials, possess a remarkable ability to respond to cellular stimuli, much like native ECM. Much like how the ECM can be remodeled by enzymes secreted from cells, this class of biomaterials responds similarly to these cellular stimuli. These biomaterials’ ability to respond to the enzymes and undergo proteolysis is crucial for proper cell migration, cell-cell contact, and force transduction132,133,134. Cell-responsive biomaterials enable the cells to directly impact their microenvironment, and this approach offers a unique opportunity to delve into cell responsiveness and explore the viscoelastic character of tissues via altered crosslinking135. Mimicking the dynamic communication between cells and their extracellular microenvironment provides valuable insights into how cells respond to changes in their mechanical environment, shedding light on the processes associated with aging-related alterations within the body. In other words, the hallmark of this class of biomaterials is their responsiveness to proteolytic remodeling, much like how the ECM changes due to aging and the presence of senescent cells.

However, there is a critical difference between cell-responsive biomaterials and native ECM. While some of these biomaterials are composed of some natural proteins, they are not “fully” natural systems. Systems that are composed of fully natural components, like Matrigel, degrade quickly, so they have an extremely limited experimental window to measure their mechanical properties129. Rather, cell-responsive biomaterials can utilize mostly synthetic materials and incorporate proteins by multiple strategies. One way is through peptide-based crosslinkers. Depending on the specific sequence of the peptide used, the biomaterial responds to different enzymes, and therefore different cellular stimuli136,137. Another method is through engineered proteins, which contain amino acid motifs from naturally occurring proteins (for example, elastin and resilin), parts of cell adhesion molecules, and proteolytically degradable sequences138. This allows the materials to act like native ECM with the added advantage of controlling cell and ECM network architecture139. Thus, these biomaterials are based on natural ECM but have slight changes to accommodate experimental constraints.

User-Tunable Biomaterials

The other major class of responsive biomaterials is user-initiated/tunable biomaterials. Instead of capturing the gradual changes the ECM undergoes, this class of biomaterials will model specific states during the aging process. Thus, these biomaterials are better suited to comparing set time points in the aging process, such as comparing an adolescent with an adult, as they have a specific set of mechanical states they can adopt74. For example, tissue generally becomes stiffer as we age, so a material that modulates from a soft state to a stiff state can be used to compare “young” versus “old” extracellular matrix.

Of note, there are several mechanisms used to control user-initiated biomaterials. The most common is light-sensitive chemistry. This capability allows researchers to exert fine-grained control over the cellular environment by modulating the biomaterial’s properties through light exposure. For instance, it manipulates the mechanical properties of the biomaterial, triggers the release of bioactive molecules, or even induces changes in cellular behavior, all using light-related chemistries140. Most of the time, light-sensitive biomaterials have modulatory stiffness properties, since the light can initiate a reaction that changes the crosslinking pattern of the material141. However, this process often is not enough to modulate the stiffness across larger areas. Instead, secondary crosslinking is photo-initiated142,143,144. This can involve the use of free radicals, potentially damaging to cells, reacting via free radical polymerization or cycloaddition reactions, a safer alternative145,146,147,148. Another consideration for the light-sensitive biomaterials is the wavelength of light safest for cell viability. Near-infrared (IR) light is lower energy and less likely to scatter, making it useful for cell work with light-sensitive scaffolds149.

An alternative scheme is to use magnetic fields enabling tunable biomaterials for user-initiated biomaterials. Magnetic fields can be applied to these materials to induce changes in their mechanical properties, or to guide the movement of magnetic nanoparticles incorporated into the biomaterial. The latter is of particular interest, as the nanoparticles can be used to limit the movement of the polymer subunits, thereby increasing the stiffness of the biomaterial150,151. This approach opens possibilities for studying cellular responses under dynamic mechanical conditions or for directing cell migration within the culture environment. However, the main advantage of this subclass over the light-sensitive biomaterials is their ability to transition between 2 states corresponding to the magnetic field being “on” and “off.” The particular benefit is reversible stiffness. User-initiated biomaterials can also include those that respond to “biological” stimuli, akin to cell-responsive materials. However, the major difference is that the biologically active stimulus is not secreted by the cells but rather introduced by the user. Bacterial enzymes are a common approach for this method152. Overall, user-initiated biomaterials are a modular approach to further dissect the role of mechanical memory in cells and distinguish the structure of the ECM during different time points in aging.

The current state of tunable biomaterials

Currently, it has been well-established that age-related changes in the extracellular matrix play a role in the progression of diseases like fibrosis in the heart & lungs and cartilage degeneration in the spine & joints153,154,155,156. These findings have prompted further studies that look at how the extracellular matrix regulates the functionality of cells, with prior work highlighting the regulatory functions of the mechanical and signaling properties of ECM59,157,158. This has led to an emerging field of designing biomaterials that induce predetermined changes in cells and tissues159,160. These biomaterials can also be “smart”/ “sensitive” in that they dynamically respond to an external stimulus such as pH or a specific secreted biomarker161.

Specific to aging, biomaterials designed to include senolytic drugs have been postulated as an avenue for the removal of harmful aging cells concurrently with the repair of the tissue, with one such example being done using quercetin to improve bone health in aged rats162,163. As a final note, there have been other treatments aimed at reducing superficial symptoms of aging, such as wrinkles. Dermal fillers address this issue by correcting the volume loss that occurs in the extracellular matrix as aging occurs156,164,165. Thus, dermal fillers are another example of biomaterials being used to reverse extracellular matrix changes as an anti-aging approach.

The future of tunable biomaterials—3-D organoids

As a complementary direction, designing biomaterials that can mimic the dynamic properties of human tissues provides an avenue for the design of synthetic organs termed organoids. Organoids are three-dimensional, miniature structures that mimic the architecture and functionality of organs166. These systems serve as models for studying organ development, disease progression, and drug responses in a laboratory environment166,167. The applications of organoids range from understanding basic cellular processes to personalized medicine166,167,168. In the context of aging, organoids offer a unique opportunity to explore the properties of human tissues over time. By designing biomaterials that can replicate the mechanical changes associated with aging and incorporating them into the organoid structure, researchers can study how the extracellular matrix evolves with age167. This approach allows for the observation of cellular responses under dynamic mechanical conditions, providing insights into the mechanical memory of cells during different stages of aging65,74. Furthermore, the stiffness achieved by user-initiated biomaterials, such as those responsive to magnetic fields, can offer an avenue for investigating how changes in mechanical cues influence cellular behavior during the aging process150,151,169. The use of biomaterials in conjunction with organoids holds great promise in tackling the complexities of aging and may contribute to the development of interventions to promote healthy aging.

Microfluidics enable recapitulation of aging on a chip

Animal models are another common experimental tool. Mice and rats are used frequently, given their similarities to humans. However, when studying aging, the short lifespan of mice and rats compared to humans presents a challenge; it becomes necessary to “map” the lifespan of the mice or other test organisms to the lifespan of a human for proper interpretation of experimental results. Additionally, genetic homogeneity and survival selection skew are additional concerns with animal studies. All these issues can be addressed using microfluidic devices; microfluidic devices can be used for “aging on chip” models.

Prior aging microfluidic devices

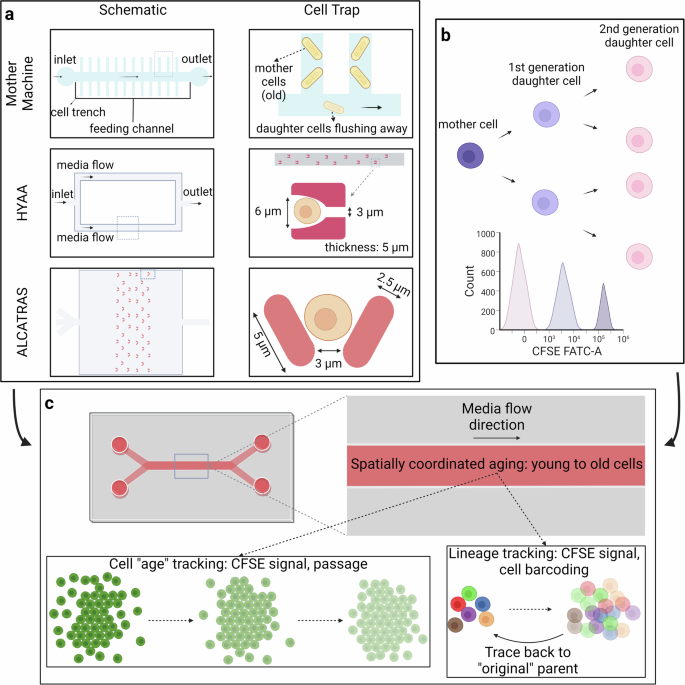

Microfluidic devices have already been used for aging studies in yeast and single-cell bacteria systems. Several systems have been published, notably: ALCATRAS (A Long-term Culturing And TRApping System), HYAA (high-throughput yeast aging analysis), and the mother machine (Fig. 4a)170,171,172. By adapting some of the underlying principles in these designs, it can be possible to create an “aging on chip” model with human cells.

a There are several existing microfluidic devices for studying aging in unicellular organisms such as yeast. The three noted ones are the Mother Machine, HYAA, and ALCATRAS, both with their overall design and the design of single-cell traps. b The use of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) allows for rudimentary “age” tracing. c Taking elements from these 3 existing aging microfluidic devices designed for yeast, along with cell generation tracking, the goal is to create a device that can track and separate cells based on lineage. Created with Biorender.com.

The first of these principles is the use of size as a mechanism for population control. Much like the HYAA and ALCATRAS, the use of traps is an effective way to “wash away” daughter cells170,171. These traps are designed to have an opening that is slightly larger than the cell, so the cells can easily fit in. The back wall is designed to have a slight gap, so the media can easily flow out of the trap, and there is minimal pressure buildup at the back wall. The overall size is just a little bigger than the size of a single cell, so the daughter cell has no place to stay. As media flows in a direction from the bigger side to the smaller side, daughter cells germinated from all directions are pushed out of the trap and float away. This enables the trapped cells to undergo the aging process uninterrupted and accurate measurements for the duration of the experiment170. Using this type of trap, the original cells would stay in the traps without being affected by overpopulation, and the aging process of each cell can be observed using a microscope and fluorescence imaging.

Microfluidic aging device for mammalian cells

The size and density of the trap should be determined based on the chosen cell’s size. Different microfluidic devices should be designed and fabricated if more cell lines with various sizes are used. Just in the case of human immune cells, the diameter can vary from 8 microns, as with B and T cells, to 20+ microns, as with monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells173,174,175,176.

Another principle that could be adopted is the use of multiple channels. This can allow not only observations of the aging process but also how senescent cells and the chemicals they secrete can affect surrounding cells and tissues. This idea allows for SASP factors secreted by the cells in the middle to diffuse into two other channels, while the media to nourish the 3 chambers is distinct177. In other words, there is a way to experimentally isolate the effects of SASP and conduct studies to “rescue” cells from SASP effects.

The fabrication of these microfluidic devices will utilize traditional lithography techniques and epoxy resins, much like most other microfluidic devices178. As detailed above, the trap design must be tailored to the cell size. Given that this device will be fabricated, it is possible to enhance the design to communicate age more clearly. One such way is to mimic the “rings” seen in trees as they age. Copying this idea, the microfluidic device could be in a “spiral” shape, so the cells grow inward. This would make it, so the outermost cells are the oldest, while the innermost cells are the youngest. Thus, there would be an association between the physical distance from the start of the channel and the relative age of the cells.

However, one important distinction between mammalian cells and unicellular organisms is the “stickiness” of the cells. Unlike unicellular organisms, which do not form firm attachments between adjacent cells, mammalian cells form membrane attachments to facilitate a variety of functions such as small molecule diffusion and barrier formation179. In a microfluidic device, this would manifest as cells clustering around the traps. Thus, the traps themselves would not be effective tools to measure “cell age.”

Rather, to properly track cells from each generation and ensure the cells we are observing are from the original generation, a cell tracker is necessary. There are several requirements for potential cell trackers: they must label cells with a fluorescent dye that can be easily observed under the microscope, the dye cannot be toxic to cells and the health & viability of cells cannot be decreased due to the cell tracker. Compared with several other cell tracking technologies, such as GFP or beta-galactosidase through viral infection or single-cell sequencing, the CellTraceTM CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit from ThermoFisher can satisfy these requirements and be used to track different generations of cells (Fig. 4b)180,181. This type of dye can easily diffuse across the cell membrane and form a covalent bind within the cells. The difference between cells within the same generation is negligible in terms of fluorescence. However, the dye will be diluted as cells divide, so researchers can distinguish cells from different generations by looking for different peaks on the flow cytometry histogram. Thus, this dye can give information that is similar to passage information. Another technique recently proposed called baseMEMOIR utilizes cell barcoding with FISH imaging to reconstruct cell lineage trees182.

This tracking dye, while useful, has one major issue for tracing cell age – it does not keep track of lineage. In other words, there is no way to be able to correctly identify which cells are the mother and daughter cells of the current cell. Cell barcoding solves this, as cells are “tagged” with specific nucleic acid sequences that are copied as cells divide183. This enables lineage tracking, as daughter cells have the same sequence as the mother cell (Fig. 4c). Combining the CFSE staining with passage information and cell barcoding will enable an “aging-on-chip” microfluidic model.

Spatial omics unravel senescence signatures in tissues and single cells

Complementary to biomaterials and microfluidics, it is equally crucial to establish a mechanism for quantifying senescence, thereby giving one way to better approximate biological age. One approach is to understand whether cellular changes are universal or tissue specific. Work has established that organs can age at different rates within the same individual, and accelerated organ aging can increase the risk for age-related diseases associated with that organ184. Additionally, understanding the relative location of these changes within cells is important, necessitating the use of spatial omics. This can also enable the construction of biological networks, enabling better models of aging185. Prior work has established clear biological patterns that distinguish senescent cells from normal, growing cells, such as differences in gene expression, chromatin content, and epigenetic factors17,54. Additionally, organelles undergo changes54. Collectively, these changes can result in the cells demonstrating the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which results in the cell altering its secretions to promote senescence in its neighbors and inflammation in tissues53,186. SASP can further exacerbate senescence-related conditions such as homeostasis loss and secondary senescence but can also result in an immune response54,69.

However, it is also noted that senescence has some important physiological functions, so it is important to also distinguish between “healthy” and “unhealthy” senescence11,187,188. Spatial omics provides an opportunity to do so, as well as distinguish universal vs tissue-specific senescence. There are many resources already existing dedicated to spatial omics analysis of aging/senescence (ex: SenNet Consortium, SenMayo)54,189. Additionally, by utilizing machine learning with these omic data sets, it may be possible to identify new biomarkers of aging and senescence as well as create aging clocks based on various data sets190,191.

Given that senescence and aging can be observed at the systemic, cellular, or molecular level and each yields valuable information, different imaging techniques based on magnification level must be used to assess senescence and aging54,192. For low-plex imaging, histochemistry, immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) are conventional strategies for spatial analysis. For high-plex imaging, spatial proteomics, and spatial transcriptomics are relatively novel and emerging strategies for multidimensional mapping of aging cells and their cell-cell communication. Additionally, super-resolution microscopy can be used to resolve finer subcellular structures and cell-cell junctions. Other post-processing techniques are used to segment the nucleus and cell cytosol in spatial data. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) allows for cell type deconvolution, tensor analysis, three-dimensional (3D)/multi-modal analysis, and deep learning methods. Of note, deep learning methods can enable finely sampled tissue mapping54.

Prior work has demonstrated that senescent cells conglomerate in microdomains and have slight differences in gene expression in various organs193. These studies provide a springboard in the quest for reversing senescence. Combining these facts with the prior discussed techniques (FISH, spatial proteomics, etc.), it is possible to evaluate the effectiveness of senolytics and senomorphics drugs aiming to stop or reverse senescence193.

Spatial omics provides a comprehensive picture of cellular senescence. Conventionally, in vitro cellular aging can be tracked with live cell imaging or fluorescent dyes in which the signal is proportional to cell division. Although general omics methods have been used to study age-related physiology and disease, spatial techniques can provide clues as to how cells age in a continuous spatial pattern69. For example, senescence has been linked to 3D changes in chromatin structure, meaning that senescence induces epigenetic changes as well194. Nuclear envelope changes and improper nuclear filament development cause changes in heterochromatin structure and thus transcription, especially upregulation of SASP. Whether this irreversible cell cycle arrest is contagious to other cells can be further investigated using spatial omics to track signaling across cell boundaries.

Spatial multiplex methods provide a more comprehensive picture of senescence54. For example, single-molecule RNA FISH methods can detect senescence-associated transcriptomic changes. Multiplex immunofluorescence or other protein detection methods (for instance, Nanostring GeoMx and CosMx platforms, along with 10x Xenium) capture the transcriptional and translational landscape of SASP at the single-cell level. One could also measure chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) and metabolomics to enhance understanding of SASP. ATAC-seq is a method that could be used to assess the formation of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF) that result in many changes characteristic of senescent cells, including that cell proliferation genes are silenced195,196. Another option for high-throughput senescence imaging is the Fully-Automated Senescence Test (FAST), which utilizes β-galactosidase activity, a known senescence marker, 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) to measure proliferation arrest and increased nuclear area to quickly assess senescence at the single cell level197. Furthermore, since single-cell senescence also impacts neighboring cells, it is imperative to study such phenomenon with spatial technologies, thus elucidating potential “hotspots” of senescence.

The senescence process behaves differently among cells of a tissue and tissues of an organism. To improve understanding of single-cell senescence, one must combine multiplexed molecular profiling methods, as stated above, and perturb time-series data to attain a complete picture. Perturbations in culture may also provide more control over senescence levels that could be confirmed by spatial omics. Many factors are known to affect aging and could be utilized in this manner. For example, gene deletions have been shown to prolong aging in yeast models198. Environmental factors such as diet and hypoxia can modulate and extend aging199. In the laboratory, cell passages can be used as representative of aging200. Additionally, the cancer drug doxorubicin has been implemented on breast cancer cell lines to induce senescence201. Furthermore, transcriptomics confirmed SASP marker (e.g. β-galactosidase) expression, metabolic upregulation (pentose phosphate, TCA cycle), and fatty acid synthesis downregulation to reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and repair DNA damage201. Thus, transcriptomics signatures are paramount to elucidating underlying biological mechanisms of senescence, while spatial transcriptomics yields neighborhoods of senescent cells in tissues.

In the brain, for example, aging has been spatially characterized at the single-cell level202. RNA sequencing and MERFISH technologies enabled single-cell profiling of the entire mouse brain (Fig. 5a). Specifically, in young compared to old mice, aging causes cell fate and transcriptomic differences in cells other than neurons (Fig. 5b). Additionally, there appeared to be immune hotspots in white matter areas of the brain. The aging of non-neuronal cells seemed to transcriptionally resemble innate inflammatory signals, suggesting some disturbance of homeostasis. On the other hand, neuronal cells exhibited signs of neurodegeneration and oxidative stress with age. Particularly, microglia and astrocytes exhibited spatially coordinated immune hotbeds in the white matter as strong signs of age (Fig. 5c). However, this immune activation was compared with prototypical immune activation induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Although many pro-inflammatory cytokines were found in both LPS and aging groups, oligodendrocyte inflammation was especially profound in aging over LPS. Therefore, the results suggest that aging-related degeneration could induce an inflammatory state that is further encouraged by other signaling factors (Fig. 5d).

a Prior research works have generally followed the pipeline shown above. Samples are collected from various age groups and characterized at the single-cell level for their gene expression. b This gene expression is analyzed and plots are generated for the different cell types, regions, and age points, as well as summarized together. c Furthermore, analysis can be done spatially based on the phenotypes of the cells; neighborhood networks can be created that show how differences in the assessed age of the cell and their location result in differences in the composition of the nearest neighboring cells. d Finally, these results can be combined to create a metric to measure age state at the single cell level, as well as map different phenomena throughout the various age groups (inflammation shown in the figure above). Created with Biorender.com.

Interdisciplinary search for multifaceted and multi-organ senescence

Reiterating, senescent cells are most notably characterized by 2 qualities: irreversible cell cycle arrest and a characteristic messaging secretome called SASP. Unlike other arrested cellular states like quiescence in which cells exit the cell cycle and go to a G0 “quiet” phase, senescence is a state where cells arrest in mainly the G1 phase but sometimes the G2 phase and remain alive for extended periods203. Due to this, senescent cells are also referred to as “zombie cells”204.

Given these characteristics, senescence does have some biological usefulness in the prevention of diseases and ailments when there is a need to prevent cell growth/proliferation or to introduce long-living cells. However, the long-term persistence of senescent cells in tissue releases more and more SASP and will trigger pro-inflammatory factors, leading to chronic inflammation and damage. In the coming sections, the role of senescence in the progression of certain diseases will be presented, both in terms of prevention/protection and progression.

Biological basis for senescence

Briefly, before the discussion of senescence and its relationship with various ailments and diseases, it is important to understand the biological basis for senescence. Senescence starts with the dysregulation of multiple stressors and conditions. This can usually be triggered by SASP secretions from surrounding cells, ROS from the immune system, DNA damage, or many other factors. The activation of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors blocks the action of CDK/cyclin complexes, preventing the phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (Rb)72. This unphosphorylated Rb remains bound to the transcription factor E2F, preventing cells from entering the S phase. This allows for senescent cells to keep growing without proliferation, indicated by the increase in cell size, lysosome level, and metabolic activity72. The increased activity of senescent cells results in the secretion of SASP, which creates a positive feedback loop and can induce secondary senescence to the neighboring cells via soluble factors and/or extracellular vesicles.

From a different perspective, the Information Theory of Aging postulates that aging is primarily driven by the loss of youthful epigenetics, resulting in the loss of cellular identity, and the recovery of this can result in age reversal205,206,207. Thus, it is important to highlight some of the notable epigenetic changes as a part of senescence and aging. One of the most studied epigenetic changes for aging is altered DNA methylation patterns. These changes have been the major focus of several age-measuring assays208,209,210. However, cost and time were major constraints for the widespread commercial use of these techniques. Recently, a new method called TIME-seq has been developed that addresses these constraints, supporting the notion that a quantitative metric to evaluate biological age may be commercially available soon211.

Specific to senescence, the most notable of the epigenetic changes is the formation of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF), which aid in the “silencing” of genes involved in cellular proliferation196,212,213. Some of the noted changes as a part of SAHF are increased histone methylation and decreased histone acetylation212,214. There is some evidence linking decreased histone acetylation with senescence215. On a related note, there is a belief that global DNA hypomethylation may be a characteristic of replicative senescence, a phenomenon observed as a part of aging216,217. Another epigenetic change related to aging and senescence involves the telomeres; these regions are noted for having CpG islands that are easily methylated, which “close” the DNA218,219. In doing so, this DNA is unable to be repaired, and the DNA Damage Response (DDR) could be activated. However, experiments involving the deletion of Gadd45a, a DDR factor, demonstrate that the ability to repair DNA in the telomere region could delay aging219,220. Given that similar epigenetic alterations have been linked to several diseases, this furthers the idea of linking aging and disease progression via senescence206.

A mechanism has been discovered for senescent cells to escape from apoptosis and also shield themselves from their pro-apoptotic SASPs, and it is called senescent cell anti-apoptotic pathway (SCAP)221. In the past decade, senolytics have been found to target SCAP, force the cells to enter the apoptotic process, and thus be eliminated by the immune system. Different branches of the senolytics have been developed to target different SCAP nodes. Senescent cells are much more sensitive to the disturbance of certain SCAP nodes than others, and different types of senescent cells use different SCAPs or even a combination of different SCAPs. Thus, more branches of the senolytics are in development to enable more accurate and effective targeting of senescent cells222. This will be further discussed in a later section.

Biomarkers of senescence

Before transitioning to discuss the role of senescence in certain diseases, it is important to note specific biomarkers of senescence, including some of the secreted biomolecules as a part of the SASP (Table 1). Among the markers for senescence, many relate to cell cycle regulation, including many of the p53 control pathway223,224. While many of the identified markers are higher in senescent cells, some notable markers are lower: E2F1, LaminB1, Ki67, anti-SAHF markers (H3K9, H3K4me3), and DNA repair markers (RPA, RAD50, RAD51)224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231. Given that the defining characteristic of senescence is the cessation of the cell cycle, it makes sense that genes related to proliferation, DNA repair, and nuclear envelope stability would be less expressed.

Additionally, given the role of the cell cycle in senescence and cancer, several markers for cancers have also been used as senescent markers15,223,232,233,234,235,236,237,238. Similarly, several of the SASP biomolecules are involved in the recruitment and activation of the immune system51,239. Other components of SASP include growth factors, proteases, ROS, PGE2, nitrous oxide, and extracellular matrix components. These markers are important to note, as they are involved in disease progression. However, Table 1 is mainly comprised of “universal” markers for senescence rather than organ- or disease-specific markers.

Senescence’s role in organ aging

For immune cells, the thymus is the organ most affected by age. It is known that the thymus undergoes involution as humans age, where functional thymus tissue is replaced with adipose tissue. This change is the biggest characteristic that defines an aged thymus. Furthermore, this process has been implicated in the accumulation of senescent T cells240,241. Additionally, it has been shown that senescence is linked with thymic involution242.

Another organ system that shows a similar pattern is the bones. The most common age-related change is the loss of density in the bone. This change has been linked with senescence, particularly the p53 pathway, given that p53 has been linked to osteoblast apoptosis243,244,245,246. Another change in bone induced by aging is the increase in adipose tissue in the bone marrow, corresponding to a decrease in hematopoietic tissue. This change has also been linked with senescence, with prior work linking altered p21 activity with this change247,248.

The brain is another of those organs for which age-related decline is noted. In a way, dementia can be viewed as an indication of age-related brain failure, given that dementia is the decline of general cognitive abilities and increases with age249,250,251. Thus, establishing mechanisms by which the brain ages could lead to insights into the progression of dementia and eventually predictors of dementia risk. Prior studies have shown the links between senescence and aging in the brain252,253,254,255. To further emphasize this, a case study has been included in the supplementary that demonstrates the link between senescence and aging in mice brain tissue. This case study demonstrated that senescence does indeed increase in aged brains, thereby supporting the notion that senescence can be used as a metric for measuring biological age.

Senescence’s role in cancer

One of the most prevalent diseases that increases in prevalence as humans age is cancer. Senescent cells play an important role in cancer prevention. When the length of the telomere has reached a critical level, the DNA damage response (DDR) is activated, which leads to cellular senescence to prevent further cell division and stop proliferation238,256. However, the DDR can be triggered by the activation of mutation in oncogenes or the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. The further activation of the senescence program prevents those affected cells from uncontrolled cell division, forcing them to stay on the G1 stage of the cell cycle and thus inhibiting tumor formation. The melanocytic nevi on the skin surface helps to illustrate this protective role of senescence when it comes to the environmental oncogenic pressure exerted by UV radiation72. Thus, senescence can act as a barrier to cancer proliferation and metastasis256. This has been observed in other cancer pathways, such as those involving cyclin-dependent kinases and specific markers such as BCL-2, p53, HER2, and MYC15,232,238,257,258,259. However, there is evidence that shows senescence can also lead to cancer, underscoring the complexity of the relationship260,261,262,263.

Senescence’s role in wound healing

Another biological phenomenon where senescence is necessary for a healthy response is wound healing. One of the stages of wound healing is inflammation as a part of clearing out damaged tissue264. Part of this includes the recruitment of immune cells, which senescent cells can aid in. Macrophages are the main immune cells involved in wound healing265. However, specific to wound healing, senescence is used to create long-lasting cells that secrete wound-healing signaling molecules. Senescence fibroblasts and endothelial cells produce several signaling molecules, chief among these molecules is platelet-derived growth factor alpha polypeptide A (PDGF-A)11,264. Additionally, these senescent fibroblasts promote wound closer by inducing the conversion of non-senescent fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, which can then contract and close the wound. When myofibroblasts become senescent, they begin degrading ECM as a method of controlling fibrosis264,266,267. In other words, senescent myofibroblasts help prevent an overabundance of scar tissue building up.

As detailed above, PDGF-A is the main signaling molecule for wound healing. It is involved in positive autocrine feedback and inducing the production of other growth factors11. However, work is being done to establish other molecules that are crucial for senescence’s involvement in wound healing. Iron has been shown to accumulate in senescent cells, possibly altering their metabolism, and to promote fibrosis268. Additionally, lipids are being explored as senescent signaling molecules involved in wound healing269,270. Given that lipid synthesis is dysregulated and wound healing is impaired as people age, there may be an underlying connection between the two. It has been established that some bioactive lipids are some of the SASP components271,272,273. Another specific example is the matricellular protein CCN1, which induces senescence in fibroblasts by binding to integrin α6β1 and can also induce the expression of antifibrotic genes via the p16INK4a/pRb pathway274. This molecule also highlights that a major part of senescence in wound healing is the regulation of fibrosis.

The control of fibrosis is an avenue for understanding scarless wound healing, which can be seen as an extension of the role of aging in wound healing275,276. It already exists biologically, as fetuses demonstrate scarless tissue regeneration. The major consensus is that fetuses are insulated from most environmental pathogens (amniotic fluid is a sterile environment), resulting in an ability to ignore the quick restoration of barrier functions276,277. In contrast, born organisms must contend with external environmental pathogens, which means that the quick restoration of barrier functions is a crucial part of wound healing278,279. This phenomenon is further emphasized by wound healing in the absence of neutrophils280. Thus, immune cells may contribute to fibrosis regulation in wound healing. However, fibrosis is not the only controlling factor in this, as demonstrated by the decrease in fibrosis in older populations277,281. Instead, cellular interactions with ECM via integrins may play a role282. This means that understanding how the different cell populations (fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, senescence fibroblasts, senescence myofibroblasts, etc.) spatially orient and interact with each other and the extracellular matrix is necessary to fully understand the biology of wound healing and possibly enable therapies for scarless wound healing283.

Senescence’s role in Alzheimer’s

While the previous sections detailed positive aspects of senescence, senescence can also negatively impact tissue and organs. One such example is the brain and the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Unlike other organs, the brain is somewhat isolated via the blood-brain barrier. This barrier is intended to provide a physical separation and regulate the flow of ions and other chemical solutes to the brain. More importantly, this barrier also prevents the spread of toxins, pathogens, inflammation, injury, and disease284. Thus, when functioning properly, the blood-brain barrier should prevent the “spread” of senescence to the brain. However, one of the effects of SASP is to disrupt the tight junctions that form this membrane. This disruption is also seen in several neurodegenerative orders285. Combined with the fact that disease prevalence increases with age, an emerging area of research is the role of senescence in neurodegenerative disorders254,286,287.

To understand how senescence is “transmitted” across the blood-brain barrier, it is important to first understand the roles of the 3 cells involved in the barrier. The first of these cells are the endothelial cells that normally compose blood vessels. For the blood-brain barrier, these cells contain tight junctions to ensure that there is no passage between the cells; rather, the passage must occur through the cells288. The next type of cells are pericytes, which are responsible for ensuring the continued maintenance of the blood-brain barrier289,290. The final type of cells are astrocytes, which are responsible for secreting factors that promote association between the various cells of the blood-brain barrier and the formation of tight junctions291. Thus, to disrupt the blood-brain barrier, one of these cells needs to be affected.

Most of the time, this disruption results from inflammatory signals, which mainly come from activated immune cells (Fig. 6a). In fact, part of SASP with immune cells is the release of inflammatory signals. One of the effects of SASP from immune cells is the increased activation of the NFκB pathway in the endothelial cells of the blood vessels292,293,294. Additionally, secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 results in the loosening of the tight junctions and the loss of the blood-brain barrier293,295. This allows for monocytes to infiltrate the brain and secrete IL-4; IL-4 results in the conversion of the microglia, resident macrophages, into pro-inflammatory macrophages286,293,296. These pro-inflammatory microglia enable the “crossing” of SASP from the blood to the brain (Fig. 6b).

a Specific immune cells are recruited from the bloodstream to certain tissues via chemokines. b In the brain, SASP “penetrates” the blood-brain barrier via the conversion of endothelial cells lining the barrier. In addition, IL-6 and IL-8 loosen the tight junctions of the barrier, enabling immune cells to enter and activate brain-resident macrophages. This allows for inflammaging in the brain. c In lymph nodes, there is a decrease in the production of IL-7, CCL19, and CCL21 resulting in impaired T cell maintenance and organization in the lymph node. d Finally, in the bone, there is a shift from equal bone formation and resorption to increased resorption & decreased formation. Additionally, there is a shift towards adipogenesis and altered cell profiles within the bone. Created with Biorender.com.

These pro-inflammatory macrophages, along with the altered endothelial cells, contribute to SASP in the brain, which results in fibrosis, ECM degradation, and collagen deposition287,293,297,298,299. Additionally, the macrophages can become lipid-laden and transform into foam cells293,299. Senescent astrocytes switch from BDNF and IGF-1 production, which stimulate healthy neuronal growth, to TNFα and IFNγ production, which trigger demyelination and inflammation of neurons253,287,293,300. The resulting DAMPs trigger further immune activation, trigger further neuronal inflammation, and create a positive feedback loop.

With all of this in mind, consider the role of senescence in the progression of Alzheimer’s. The defining pathological marker for Alzheimer’s is the accumulation of Aβ peptide amyloid plaques, but no definitive link with senescence has been established253,301,302,303,304,305. Currently, it has been noted that aged microglia lose their ability to phagocytose Aβ fibrils and then undergo replicative senescence306,307. Instead, changes due to senescence have been observed in specific cell types. Most prominently, there is a progressive loss of neuronal stem cells that can be attributed to the loss of neural progenitor proliferation due to senescence308,309,310,311. Furthermore, there is evidence of senescent neural stem cells in Alzheimer’s312. The other prominent cell line affected are astrocytes. They demonstrate an inflammatory and neurotoxic state and contribute to neuroinflammation313,314,315.

Senescence’s role in osteoporosis

Another example of senescence negatively impacting an organ and disease progression is osteo-degenerative diseases like osteoporosis. Given that the bone marrow is a primary lymphoid organ, it is also important to note the contribution of immune cells towards osteoporosis and bone aging. Before getting directly to the bone marrow, first consider how aging influences lymph nodes, the major secondary lymphoid organ. The major immune cells in lymph nodes are T cells. High endothelial venules in the lymph nodes produce CCL19 and CCL21, which are needed for the positioning of T cells and dendritic cells in lymph nodes316. Additionally, IL-7 is produced by fibroblastic reticular cells and lymphatic endothelial cells, which is necessary for mature T cell homeostasis and survival317,318,319. As a part of aging, the production of all 3 of these molecules is reduced, resulting in impaired T cell maintenance (Fig. 6c)317,320. T cells are part of a positive feedback loop that exacerbates some of the changes brought about by senescence, meaning that lymph node dysregulation could be contributing to this issue.

The major cell in this case is the macrophage321. These cells are influenced towards their M1 state (inflammatory state) by the over-accumulation of apoptotic neutrophils and NETs (neutrophil extracellular traps)322. This skewing, combined with macrophage overactivation, results in excessive T cell activation and T cell exhaustion321. These T cells further contribute to the macrophage skewing, creating yet another positive feedback loop. Additionally, B cells can infiltrate the bone. These 4 immune cells can then each promote bone resorption and inhibit bone formation via different mechanisms: 1) inflammatory macrophages secrete IL-1β, TNF-α &IL-6, 2) NETs from neutrophils, 3) the affected T cells have increased IL-17 secretions & decreased TBF-β secretions and 4) B cells secrete RANKL321,323,324,325,326,327,328,329.

Before delving into osteoporosis and the role senescence plays in bone resident cells, it is important to briefly highlight one of the key mechanisms in bone homeostasis – the balance of activity between osteoblasts, which promote bone formation, and osteoclasts, which promote bone breakdown (resorption). They are regulated by WNT signaling and RANK/RANKL signaling respectively. Crucially, communication between the two occurs via osteoprotegerin, which is secreted by osteoblasts to inhibit osteoclast activity330,331. Bone remodeling is a sequence that involves both cells: activation of osteoclasts to breakdown damaged/old bone, resorption of bone, reversal whereby osteoblasts are activated & osteoclasts inactivated, and formation of new bone332,333.

During aging, there are two major changes in relation to bones. First, bone marrow becomes replaced with adipose tissue334,335. This results in a lower pool of bone marrow stem cells, particularly mesenchymal stem cells, which are crucial for osteoblast generation. Second, the loss of hormonal signaling results in an altered balance between the activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts336,337. Collectively, both changes result in bone loss and possibly osteoporosis. It has been shown that aging mainly inhibits osteoblast activity by promoting adipogenesis and decreased WNT signaling338,339,340.

Senescence contributes to the inhibition of osteoblast activity but also impacts other cell types. The major cell propagating senescence in bone is the adipocytes (Fig. 6d)341,342. These adipocytes are influenced by bone marrow stem cells. Bone marrow cells aid in the change from osteoblastogenesis to adipogenesis, as well as increase the activity of the adipocytes341. Once this occurs, the adipocytes secrete a variety of molecules called adipose derived factors, each influencing another set of cells342,343. Adipsin secretion creates a positive feedback loop by priming the initial bone marrow stem cells towards adipogenesis344. RANKL secretion increases osteoclastogenesis, while adiponectin secretion causes skewing in myeloid hematopoietic stem cells345,346,347,348. Lastly, the SASP secretions result in a conversion of normal bone marrow stem cells to senescent ones349.

Drugs targeting senescence

Given how many diseases are linked to senescence, some treatments target senescence. Broadly, two main classes of drugs target senescent cells: senolytics, which kill senescent cells, and senomorphics, which modify senescent cells69. Senolytics are drugs that target and kill senescent cells350. Senomorphics are drugs that suppress markers of senescence, particularly the SASP351. Some senolytics and senomorphics are shown in Table 2. Among the drugs in Table 2, there are a few notable ones. Dasatinib and Quercetin were the first senolytics discovered and are still the most popular ones222. Quercetin targets the BCL-2 family members and p53 and p21 SCAP nodes while Dasatinib targets the tyrosine kinase of SCAP (senescent cell anti-apoptotic pathway)221. Also, Nutlin3a is part of the senolytics family but has been noted to cause senescence as well352.

More generally, senolytics and senomorphics can be classified into broad categories based on their mechanism of action351. One of the main classes of senolytics is Bcl-2 family member inhibitors353,354,355. Another class targets HSP90 (heat shock protein 90)356,357. The major class of senolytics is p53 pathway targeting compounds; there are several subclasses including FOXO4-p53 inhibitors, MDM2/p53 inhibitors, and USP7 inhibitors358,359,360,361,362,363,364,365. Additionally, there are some natural products and analogs that are senolytics366,367,368,369,370,371,372,373. Similarly, for senomorphics, one of the main classes is NFκB inhibitors374,375,376,377. Other classes include p38MAPK inhibitors, JAK/STAT inhibitors, and ATM inhibitors234,378,379,380,381,382. There are also some natural products and analogs that are senomorphics383,384,385,386. However, there are more notable, and therefore standalone, senomorphics such as rapamycin, metformin, resveratrol, and aspirin387,388,389,390.

An emerging approach with senolytics is the use of galactose-modified senolytics pro-drugs that target senescent cells due to their elevated lysosomal β-galactosidase activity391,392,393,394. More generally, there are concerted efforts to link drugs to specific pathways that are modulated as a part of senescence, as detailed in the prior paragraph351. Another emerging approach is specific to cancer senescent cells. Metal complexes are being researched as a way to induce senescence in cancer cells to limit the growth of the tumor, and then senolytics can be used to kill these cells, along with the rest of the cancerous cells395. These two approaches once again highlight the “balancing act” that is senescence; it is a biologically useful phenomenon but can be detrimental if not properly regulated.

Anti-aging treatments

With the emphasis on staying young today, there are several “anti-aging” products and regimens sold and available to try. However, many of the popular treatments, particularly anti-wrinkle skin care treatments, treat the symptoms rather than the underlying causes. In other words, they do not address cellular issues brought about by aging, such as senescence. A summary of some of the most used “anti-aging” remedies/treatments are listed in Table 3. The first major class of treatments listed are related to skin care, particularly wrinkle prevention. As previously mentioned, these are not true anti-aging treatments as they focus only on treating a symptom. Similarly, the procedures of Botox, dermabrasion, and dermal fillers address the same symptom rather than the underlying issue396,397,398. However, it should be noted that Botox is being looked at for the treatment of other ailments, suggesting it could be used for other age-related issues399,400. Instead, there are vitamins/supplements and lifestyle choices that have been linked to slowing the progression of aging.

Many vitamins and supplements exist in natural sources. For example, curcumin can be found in turmeric, crocin in saffron, theanine in green tea, resveratrol in berries, vitamin C in citrus fruits, vitamin E in nuts & fish, and rhodiola & astragalus as themselves. Others can be taken via supplements such as collagen, Coenzyme Q10, NAD+ precursors like vitamin B3, and α-ketoglutarate. Each of these supplements generally targets a few organ systems rather than the body as a whole. Similarly, there are lifestyle choices that can help slow the progression of aging. Some dietary approaches include caloric restriction, plant-based diet, and intermittent fasting. Exercise has also been linked to slowing aging down, as well as stress management. Exercise has been linked with reducing circulating SASP factors and reduced senescence in some cellular populations401,402,403,404.

Currently, there has been increased interest in the idea of plasma transfusion from younger donors, a procedure known as plasmapheresis. This method has been shown to help slow the decline of neurogenesis & cognitive function, lower oxidative stress & inflammation, improve skin aging, and reduce the risk of age-related diseases405,406,407,408. While the exact mechanisms by which this method helps combat aging are unknown, it is known that younger plasma can dilute systemic “age-promoting” factors that reset some signaling pathways back toward their “youthful” state409,410. This idea could be extended to senescence as postulating that plasmapheresis clears out harmful SASP factors circulating in the bloodstream.

Altogether, aging is an area of great interest given its increasing burden on healthcare. As we age, several changes occur in the body, necessitating a multi-faceted approach to studying aging. By combining the dynamic capabilities of biomaterials, the design architecture of microfluidics, and the single-cell analysis provided by spatial omics, a clearer assessment of aging can be made. This can open avenues for treatments and preventive care for both general anti-aging and slowing the progression of age-related diseases.

Responses