Association between gut microbiota and locomotive syndrome risk in healthy Japanese adults: a cross-sectional study

Introduction

Japan was one of the first countries worldwide to face the challenges of a super-aging society, with an increasing life expectancy and a prolonged unhealthy period burdening the social security system1. An unhealthy period is defined as a period when a person requires nursing care and support, resulting in declined activity of daily life (ADL) and quality of life (QOL). Extending healthy life expectancy is a global health issue related to population aging. Despite efforts to extend healthy life expectancy through exercise, diet, and smoking cessation, which increased by 1.8–2.3 years from 2010 to 2019, the unhealthy period improved by only 0.4–0.6 years, suggesting that reducing unhealthy periods requires additional strategies1. Thus, preventing conditions requiring care and support, which are significant causes of unhealthy periods, is indispensable to resolving the discrepancy and reducing unhealthy periods.

Japan’s long-term care insurance system supports individuals requiring care based on their mental and physical conditions. In 2022, 7.0 million people (19.0% of those aged >65 years) were certified under this system, with the actual number likely higher due to voluntary application1. Musculoskeletal dysfunction significantly contributes to this unhealthy period, accounting for approximately 25% of cases requiring long-term care. This proportion rises to 54.6% when including related conditions like cerebrovascular disease and frailty1. Therefore, preventing musculoskeletal dysfunction is crucial for maintaining ADL and QOL, thereby reducing the unhealthy period. The concept of locomotive syndrome was introduced by the Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) in 2007 to describe a condition of reduced mobility due to age-related impairment of locomotive organs1,2. Early detection and intervention for locomotive syndrome are crucial to prevent a reduction in mobility due to musculoskeletal dysfunction2.

Long-term care prevention strategies often include exercise and dietary interventions3. Exercise not only directly enhances physical function but also indirectly affects gut microbiome diversity4. Recent studies have emphasized the gut microbiome’s importance in various aspects of human health, extending beyond gastrointestinal diseases5,6. Several studies have reported potential benefits of modifying the gut microbiome environment in managing conditions such as diabetes, liver disease, and depression5,6,7,8. While research suggests that physical activity may benefit gut microbiome composition and contribute to healthy aging9, the exact biological mechanisms remain unclear. Moreover, the specific role of the gut microbiome in age-related musculoskeletal decline requires further investigation.

This study aims to investigate the association between gut microbiome composition and musculoskeletal function, focusing on the risk of locomotive syndrome in healthy population. We hypothesized that specific gut microbiota may be associated with locomotive syndrome, potentially offering new insights into the pathophysiology of the decline in musculoskeletal function. By clarifying this association, we believe the gut microbiome could serve as a tool for long-term care prevention. For instance, if the gut microbiome influences musculoskeletal function, changes in nutrient absorption due to altered gut microbiota might be a contributing factor. In this case, interventions to improve the gut microbiome environment could be effective. Conversely, if musculoskeletal dysfunction affects the gut microbiome, the resulting alterations might further impair musculoskeletal function.

Using microbiome analysis techniques and machine learning approaches, we aim to identify specific microbial taxa and functional pathways associated with locomotive syndrome. Our findings could provide a foundation for developing targeted interventions to prevent or mitigate locomotive syndrome, contributing to the extension of healthy life expectancy in aging populations. To achieve this goal, we performed a cross-sectional analysis using data from a cohort of healthy individuals in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the 577 participants with available 16S rRNA gut microbiota data, nutritional data were unavailable for three participants, and 5-question Geriatric Locomotive Function Scale (GLFS-5) scores were unavailable for six participants. Therefore, 568 participants (209 males [36.8%]) were included in the analysis. Table 1 presents the participants’ characteristics. The median age (inter-quartile range: IQR) was 58.5 (48.0–71.0) years, and the median (IQR) of GLFS-5 was 0.0 (0.0–3.0). In the GLFS-5 positive group (99/568 [17.4%]; 31 males [31.3%]), the median (IQR) age was 74.0 (71.0–78.0), and the median BMI was 22.6 kg/m2 (20.9–24.6). Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the complementary cumulative distribution function (CCDF) analysis of GLFS-5 scores. The 568 participants included in this study showed a slightly higher proportion of individuals with elevated GLFS-5 scores compared to the remaining cohort participants.

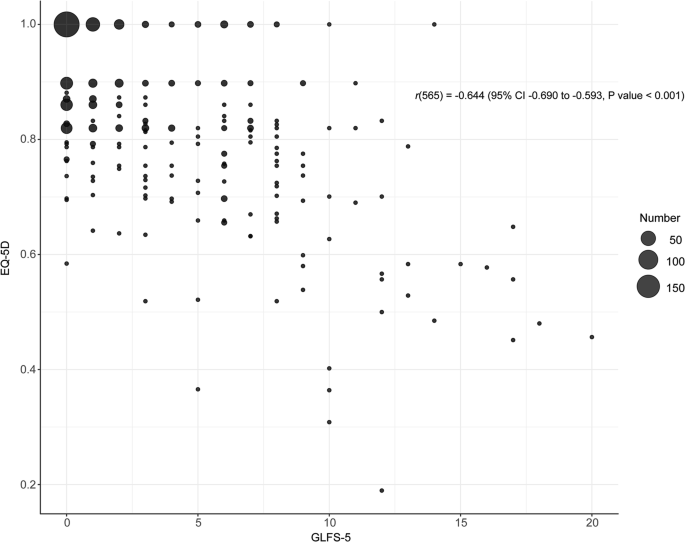

Association between GLFS-5 and EQ-5D

The association between GLFS-5 and EuroQoL 5-Dimension 5-Level (EQ-5D) is illustrated in Fig. 1. These two measures showed a correlation of r(565) = −0.644 (95% confidence interval −0.690 to −0.593, P < 0.001). The median EQ-5D scores (IQR) were 1.000 (0.860–1.000) for the GLFS-5 negative group, and 0.763 (0.656–0.832) for the GLFS-5 positive group, respectively (Table 1).

This bubble plot illustrates the association between GLFS-5 (x-axis) and EQ-5D (y-axis) scores. Each bubble represents a group of participants, with bubble size indicating the number of participants (see legend). Pearson’s correlation coefficient between GLFS-5 and EQ-5D was r(565) = −0.644 (95% CI: −0.690 to −0.593, P < 0.001), indicating a negative correlation. GLFS-5 5-question geriatric locomotive function scale, EQ-5D EuroQoL 5-Dimension 5-Level, CI confidence interval.

Gut microbiota composition and functional analysis

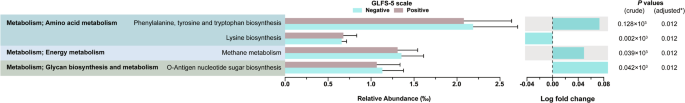

Table 2 presents the result of linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) analysis. LEfSe revealed an enrichment of Actinobacteria (LDA score = 7.02) and a depletion of several Firmicutes genera (e.g., Eubacterium xylanophilum group, LDA score = −4.71) associated with the presence of locomotive syndrome. Phylogenetic investigation of communities by reconstruction of unobserved states (PICRUSt2) analysis predicted several functional pathways related to metabolism, such as amino acid metabolism, although the log fold change (LogFC) for these pathways was all less than 1 in absolute value (Fig. 2).

The figure shows differential abundance of predicted metabolic pathways between GLFS-5 positive (locomotive syndrome) and negative groups. Results are filtered with adjusted P < 0.05 and absolute log fold change >0.04. Left panel displays relative abundance (‰) of pathways, with error bars indicating standard error. Right panel shows log fold change between groups. P values (crude and adjusted) are presented on the far right. GLFS-5 5-question geriatric locomotive function scale. *P values were adjusted using false discovery rate method.

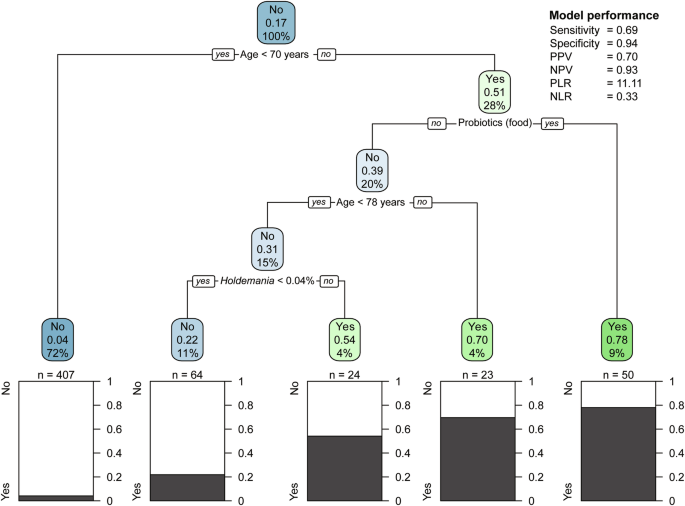

Classification tree analysis of locomotive syndrome risk factors

The results of the classification tree analysis are shown in Fig. 3. We used class to genus level operational taxonomic units (OTUs) belonging to Actinobacteria and Firmicutes as input for microbiota. Of the five terminal nodes, three were classified as GLFS-5 positive. The branching conditions were age, probiotic (food) intake, and the Holdemania genus. In the terminal node meeting the following conditions, 39/50 (78.0%) of the classified participants were positive for GLFS-5; age ≥ 70.0 years and probiotics (food) consumption. The median (IQR) GLFS-5 score for this node was 8.0 (6.5, 9.0) points. Table 3 presents the characteristics of the groups classified as GLFS-5 positive and negative. Of the 568 participants, 97/568 (17.1%) were classified into the GLFS-5 positive node, with 68/97 (70.1%) of these participants being positive for GLFS-5. Consequently, the classification tree analysis yielded a sensitivity of 0.69, specificity of 0.94, positive likelihood ratio of 11.1, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.3. Supplementary Fig. 2 illustrates the relative abundance of Holdemania genus according to age groups.

The tree shows branching based on age, probiotic food consumption, and relative abundance of Holdemania genus. Each node displays the predicted outcome (Yes/No for locomotive syndrome risk), the proportion of positive cases, and the percentage of total samples in that node. Terminal nodes show the distribution of actual outcomes. Statistical measures of the model’s performance are provided (right). PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value, PLR positive likelihood ratio, NLR negative likelihood ratio.

Characteristics of classification tree nodes

The terminal node associated with the microbiota was identified under the following conditions: age ≥ 70.0 and < 78 years, no probiotics (food) consumption, and a relative abundance of Holdemania genus ≥0.04%, as shown in node 1 in Table 4. This node exhibited the highest MVPA (median [IQR] 10.4 [8.0–18.1]) compared with other groups, including the negative terminal nodes (median [IQR] 8.7 [4.0–16.4]). In the terminal node, where participants consumed probiotics (food), 37/50 (74.0%) participants were also consuming natto, a proportion that was higher than that in the other groups.

Discussion

This study examined the association between locomotive syndrome (an indicator of musculoskeletal dysfunction) and the gut microbiota in healthy Japanese adults. Our findings suggest that an enrichment of Firmicutes, especially an increased relative abundance of Holdemania, was associated with positive screening results for locomotive syndrome under specific conditions.

The results of the classification tree analysis showed that participants with a relative abundance of Holdemania 0.04% or greater and aged between 69.5 and 77.5 years who did not consume probiotics foods were associated with an increased risk of locomotive syndrome (Fig. 3). Previous research has reported a negative association between the relative abundance of Holdemania and both an increase in skeletal muscle mass and a prolongation of one-leg standing time with eyes closed following exercise intervention10. The highest MVPA observed in the terminal node containing Holdemania is consistent with this evidence. Decreased skeletal muscle mass is an important factor in locomotive syndrome1. Taken together, these findings suggest that participants with a relative abundance of the Holdemania ≥ 0.04% may have lower skeletal muscle mass and consequently an increased risk of locomotive syndrome risk.

A previous study has suggested an association between frailty, which is related to a decline in musculoskeletal function in older adults, and the gut microbiome11. This study reported a negative association between frailty and the relative abundances of Corpobacillus and Veillonella. Holdemania and Corpobacillus belong to the common order Erysipelotrichales, with Veillonela in the common class Negativicutes. The concepts of frailty and locomotive syndrome share similarities, as frailty is a state in which age-related decline in motor and cognitive function impairs the vitality of the body and mind and is also affected by comorbid illness, but its decline can be reversed with appropriate intervention and care12. As Holdemania is classified in the same bacterial lineage as previously reported frailty-related microbiomes, our results suggest a potential involvement of the gut microbiome in locomotive syndrome and musculoskeletal function.

The conditions for the branching in the classification tree analysis other than the microbiota were age and probiotics (food). The association with age is consistent with existing evidence that age is a risk factor for locomotive syndrome1. A survey of the prevalence of locomotive syndrome in Japan revealed that the prevalence tended to increase sharply from the age of 70 years13. Specifically, the prevalence of locomotive syndrome was 8.4% for those in their 40 s, 9.2% for those in their 50 s, 8.3% for those in their 60 s, and 16.3% for those in their 70 s. The first branching condition in the results of the classification tree analysis is age 70 or older, which aligns with existing evidence. However, the positive association between probiotic (food) consumption frequency and the risk of locomotive syndrome contradicts existing evidence; in fact, consuming probiotic food is recommended to prevent osteoporosis14. We posit that this finding may be due to reverse causation, reflecting that participants who were aware of their reduced mobility may have been more careful in consuming probiotic foods to maintain or improve their musculoskeletal function or prevent the development of locomotive syndrome. The observation that the EQ-5D scores were higher in the GLFS-5 positive group further supports this interpretation. The same reasoning could explain the high number of participants in this group taking natto.

Our LEfSe analysis revealed several notable associations between gut microbiota composition and locomotive syndrome risk. Notably, we observed an enrichment of Actinobacteriota phylum in individuals with higher locomotive syndrome risk. Actinobacteriota is known to be associated with various health outcomes, including metabolic disorders and inflammatory conditions15. The enrichment of this phylum may suggest a potential link between certain metabolic processes and musculoskeletal health. Conversely, we observed a depletion of several Firmicutes genera, including members of the Lachnospiraceae family such as the Eubacterium xylanophilum group. Lachnospiraceae are known for their ability to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which have been implicated in various beneficial health effects, including anti-inflammatory properties15,16. The depletion of these bacteria in individuals with higher locomotive syndrome risk might indicate a potential reduction in SCFA production, which could contribute to increased inflammation and potentially impact musculoskeletal health. This finding aligns with our previous discussion on age as a known risk factor for musculoskeletal decline, as the age-related decrease in Lachnospiraceae abundance is consistent with its association with locomotive syndrome17. These findings complement our earlier observations regarding the association between Holdemania abundance and locomotive syndrome risk. Holdemania, like many of the depleted Firmicutes genera identified in our LEfSe analysis, belongs to the order Erysipelotrichales. This consistency in our findings strengthens the potential link between changes in Firmicutes composition, particularly within the Erysipelotrichales order, and locomotive syndrome risk.

We were unable to identify differentially abundant functional pathway in our PICRUSt2 analysis, including those involved in amino acid metabolism and energy metabolism, with clinically meaningful differences ( | LogFC | > 1). Consequently, we were unable to explore potential relationships between specific microbial metabolic functions and dietary factors that might influence locomotive syndrome risk. However, despite these limitations in our functional analysis, our approach utilizing classification tree analysis enabled us to assess non-linear associations and interactions between variables18,19, leading to the identification of Holdemania as a potential biomarker for locomotive syndrome risk.

The association between Holdemania abundance and locomotive syndrome risk, particularly in the context of age and probiotic consumption, suggests a potential avenue for targeted interventions. Although we were unable to establish direct functional links, the consistent association of Firmicutes-related changes (including Holdemania) with locomotive syndrome risk points to the possibility that dietary interventions aimed at modulating these bacterial populations might be beneficial20. Future research should focus on understanding the specific metabolic functions of these bacteria and how they might be influenced by diet or probiotic supplementation to potentially mitigate locomotive syndrome risk.

This study had several limitations. First, we were unable to directly analyze the association between the gut microbiota and skeletal muscle mass due to a lack of data. Second, because this was a cross-sectional study, causal relationships could not be inferred. Further evaluations using longitudinal or interventional studies are necessary. Third, the assessment of locomotive syndrome was conducted using the GLFS-5, a self-administered questionnaire, which may not accurately reflect the actual degree of musculoskeletal function due to its self-reported nature. Additionally, people with early musculoskeletal dysfunction may be unaware of their potential risk, which could lead to misclassification. Future studies should include objective physical performance measures such as gait speed and balance tests. Fourth, the association between Holdemania and locomotive syndrome was observed under specific branching conditions; thus, this study could not assess independent effects. Other limitations include selection bias resulting from using data from a genomic cohort study of healthy individuals. In our study, the prevalence of locomotive syndrome was 17.4%, substantially lower than the 34.1% prevalence reported for adults aged 60 years and older in Japan, suggesting that individuals who already had reduced musculoskeletal function at a certain level were not included. However, as the study aimed to elucidate evidence for primary or secondary prevention, the analyzed population was similar to the population to which we aimed to generalize the results21. Furthermore, CCDF analysis showed that the participants included in the current analysis slightly overrepresented higher-risk individuals. However, this may have enhanced our ability to detect associations between gut microbiota and GLFS-5.

In conclusion, classification tree analysis revealed an association between Holdemania and locomotive syndrome, which reflects musculoskeletal function. Future research, including prospective studies that can clarify causal relationships, is necessary to further elucidate the role of the gut microbiome in musculoskeletal health and locomotive syndrome. Such studies could potentially inform the development of preventive interventions utilizing gut microbiome information to reduce the risk of locomotive syndrome and extend healthy life expectancy.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This study employed a cross-sectional design, utilizing data from the Kanagawa “ME-BYO” Prospective Cohort Study (the ME-BYO cohort). The ME-BYO cohort is a collaborative institution of the Japan Multi-Institutional Collaborative Cohort (J-MICC) Study. Details of the J-MICC Study and its association with the ME-BYO cohort have been described elsewhere22,23. Briefly, the J-MICC Study was conducted by 13 research institutions located in 12 prefectures of Japan under a standardized protocol. The baseline survey of the ME-BYO cohort started in 2016 and was ongoing as of 2024. The eligibility criteria for the ME-BYO cohort were living or working in Kanagawa Prefecture and being aged 18–95 years. Among the 3409 participants enrolled by the end of March 2022, we used data from 577 participants for whom gut microbiota data were available. To assess the representativeness of our study sample, we conducted a CCDF analysis of the GLFS-5 scores to compare the distribution of GLFS-5 scores between the selected 577 participants and the remaining cohort participants. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All research procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Kanagawa Cancer Center (Approval No. 28KEN-36).

Measurements

An examiner performed anthropometric measurements, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated from height and weight. Lifestyle and health condition data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire. We used the age at the time of recruitment. Daily nutritional intake was evaluated using a validated food frequency questionnaire24,25. To account for individual differences in total energy intake, we adjusted nutrient intakes using the residual method. We selected the following nutrients for analysis that are known to be beneficial to the human gut microbiota: omega-3-unsaturated fatty acids (n3PUFA), omega-6-unsaturated fatty acids (n6PUFA), saturated fatty acids (SFA), soluble dietary fiber (SDF), and insoluble dietary fiber (IDF)26,27,28; these nutrients facilitate the metabolism of beneficial bacteria and promote their proliferation26,27,28. Nutrients associated with the musculoskeletal system include total energy intake, protein, folate, vitamins (A, B1, B2, E, and D), and calcium29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Alcohol intake (g/day) was also assessed. Smoking status was assessed as currently smoking, coded as 1, and other answers, such as quit or never smoked, as 0. Daily physical activity was evaluated based on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire in metabolic equivalents hours per day (METs-h/day), and activities higher than 3.0 METs were classified as moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA)37. To account for potential confounding factors affecting gut microbiota composition, we assessed participants’ exposure to factors known to influence gut microbiota. Participants were considered exposed to antibiotics if they had taken such medications within the past two weeks. Exposure to probiotics was evaluated in two categories1: probiotic medications taken within the past two weeks, and2 probiotic-rich foods consumed more than three times in the last week. These probiotic-rich foods included fermented products such as yogurt containing Lactobacillus and natto (fermented soybean) containing Bacillus subtilis natto. All these factors were included in our analysis as potential confounding variables due to their known effects on gut microbiota. Postmenopausal females and all males were treated as participants without menstruation. Medical histories of stroke, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and malignant tumors were also incorporated into the analysis.

Assessment of musculoskeletal function

To evaluate locomotive syndrome, we used GLFS-5, a short-form version of the 25-item original questionnaire38,39. The GLFS-5 is a 5-item questionnaire that uses a 5-point Likert scale, with a final score ranging from 0 to 20 points, where a higher score indicates a higher risk and a cut-off value of 6 points indicates the presence of locomotive syndrome. The GLFS-5 data were also collected from the baseline questionnaire of the ME-BYO cohort. Additionally, to facilitate international comparison, we analyzed the relationship between GLFS-5 and EQ-5D, a widely used measure of health-related QOL, which was used in the validation paper of GLFS-2538. EQ-5D-5L assesses health-related QOL in five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression), with five levels (no, slight, moderate, severe, and extreme problems)40,41. The score ranges from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates full health. We performed correlation analysis between GLFS-5 and EQ-5D scores, and compared EQ-5D scores between groups classified by the GLFS-5 cut-off score (≥6).

Gut microbiota data

At enrollment, we distributed the fecal specimen collection kits, which were brush-type kits containing guanidine thiocyanate solution (Techno Suruga Laboratory, Shizuoka, Japan), and instructed the participants to return the kits via post mail to the laboratory. The methods used to obtain microbiota data have been described elsewhere42,43,44. Short-amplicon 16S rRNA gene sequencing targeting the V1–V2 region was performed using the 27 F forward and 338 R reverse primers and clustered by gene-specific taxonomic classification based on the QIIME2 pipeline (version 2020.8)44. After clustering, the sequences were classified for taxonomic assignment using the robust taxonomy simplifier for SILVA (arts-SILVA), which was originally developed from the 16S rRNA taxonomy dataset based on SILVA 13845. Data at the phylum to genus taxonomy level were used, and the relative abundances of 1121 OTUs were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

LEfSe was used to detect microbiota that are associated (P < 0.06 × 103 [0.05/1121 OUTs] and LDA score > 0.2) with the presence of locomotive syndrome using the lefser function in lefser package. To analyze the functionality of the gut microbiome, we conducted PICRUSt2 and visualized the results using the pathway_errorbar function in the ggpicrust2 package. P values were adjusted using the false discovery rate, and LogFC was calculated to quantify differences between groups. The result of PICRUSt2 analysis was filtered by adjusted P < 0.05. In addition, we employed decision tree analysis, a method particularly suited for exploring complex, non-linear relationships in biological data. This approach allows for the identification of key variables and their interactions without assuming a predetermined model structure, making it ideal for investigating the potentially intricate associations between gut microbiome composition and locomotive syndrome risk. We used results of the LEfSe analysis as an initial screening step to identify relevant phyla for further investigation: we focused on the OTUs from class to genus level that belonged to phyla that showed evidence for an association.

This method is used in clinical evaluations, such as disease prediction and screening46,47. The advantage of classification tree analysis is that no distribution assumption is required, and nonlinear associations can be handled, as it is a nonparametric procedure18,19. The analysis was not affected by outliers, collinearities, heteroscedasticity, or distributional error structures that affect parametric procedures18. Furthermore, the classification structure obtained from the analysis is explicit and easy to interpret. Since the microbiota data we used were relative abundances, excess zero values were included; thus, we adopted classification tree analysis. Classification tree analysis was performed using the ‘rpart’ function of the rpart package48. The predictive variable was the GLFS-5, and age, sex, BMI, lifestyle factors described in the measurement section above, and the gut microbiota were used as inputs. We set the minimum terminal node size to 20 observations and performed cost-complexity pruning (CP). We obtained the CP parameter by five-fold cross-validation with ten times repeat using the train function in the caret package and set it to 0.0249. All analyses were performed using the R software (version 4.2.1 and 4.4.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)50.

Responses