Cell senescence in cardiometabolic diseases

Characteristics of senescent cells

Identification of senescent cells

To date, not a single, specific marker for cell senescence exists. As such, we need to use a combination of markers to identify senescent cells. Besides the original observation by Hayflick that the progressive loss of telomeres leads to a permanent cell cycle arrest, cellular senescence can be triggered by various forms of DNA damage, including double-strand breaks (DSB) at global or telomeric DNA, inflicted by several inducers such as oxidative stress, radiation or chemotherapeutics1. As such, cell senescence can be classified into three subtypes: replicative senescence (due to telomere shortening), oncogene-induced senescence (e.g. induced by oncogene activation) and stress-induced senescence (e.g. induced by oxidative stress, chemotherapeutics)1. The irreversible growth arrest is regulated by the activation of cell cycle inhibitors, such as the tumor suppressor protein p53, and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p16INK4a and p21Cip16. Both p16 and p53/p21 can be involved in various forms of cell senescence. SAβG, short for senescence-associated beta-galactosidase, is another marker of cell senescence that is often (exclusively) used to identify senescent cells1, yet a word of caution is needed when using SAβG in vitro and in vivo. So far, SAβG has been found to be a reliable marker for the detection of senescent endothelial cells7 and smooth muscle cells8, but it may show false-positive staining in cells with a high lysosomal content9. For example, it was found that bone-marrow-derived macrophages after 7 days in culture show 96% SAβG+ whilst being highly proliferative, making SAβG an unsuitable marker for macrophage senescence10. This means that one needs to be cautious when applying SAβG staining on macrophage-rich tissues such as atherosclerotic plaques, hearts with cardiomyopathies (e.g. myocarditis) and adipose tissue. Two independent studies found that bone-marrow-derived macrophages also express high levels of p16 upon differentiation, even when they are proliferative9,10, indicating that both SAβG and p16 are not suitable to identify macrophage senescence. Along these lines, not a single SASP factor has been discovered yet that exclusively labels senescent cells. Indeed, all traditional SASP factors (e.g. IL6, TNFα) can be expressed by activated macrophages, other leukocytes or other (dying) cells that are not senescent. To date, it is not known how many senescent cells are present in any given tissue, yet the frequency is estimated to be quite low. Nevertheless, the majority of in vivo studies only uses SAβG as a senescence marker, and reports SAβG activity ranging from a few percentages11 to more than 20%12 in atherosclerotic tissues. In a rat model of diastolic heart failure, 20% of immune cells in the heart were found positive for SAβG compared to 10% of endothelial cells13. Hence, the lack of having a clear estimation of the number of senescent cells in the aged or diseased tissue makes it more difficult to determine the true impact of cell senescence on aging and disease.

Autocrine and paracrine effects of senescent cells

Senescent cells have significant autocrine and paracrine effects, which are crucial for understanding its impact on the surrounding cellular environment. Senescent cells often reinforce their own senescent state through autocrine signaling through the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL6) and growth inhibitors that act on receptors on the same senescent cell (reviewed in ref. 14). These signals can further maintain the cell cycle arrest, promote inflammation, and remodel the extracellular matrix14. Senescent cells can also have paracrine effects through the secretion of factors that promote inflammation, DNA damage or proliferation of neighboring cells15,16. In some cases, the SASP can induce a senescent state in healthy neighboring cells, a phenomenon termed ‘paracrine’ or ‘bystander’ or ‘secondary’ senescence17. This further leads to SASP amplification, creating an environment of chronic inflammation, driving a positive feedback loop of senescent cell accumulation18. Besides being released as soluble factors, the SASP can also be packed in extracellular vesicles (EV) such as exosomes. These EV contain proteins, lipids and nucleic acids (e.g. miRNA) and may play a central role in paracrine senescent signaling16,19. Indeed, it has been shown that senescent cells often secrete a greater number of EV compared to non-senescent cells20. The concept of cell senescence spreading implies that even a small number of senescent cells can have a destructive and pathological impact on healthy tissue. Indeed, the chronic SASP is presumed to be responsible for the age-related decline in tissue function by causing a low grade of chronic inflammation21. Of course, it must be noted that paracrine signaling of senescent cells is not always detrimental. In case of tissue repair and regeneration, the SASP can attract immune cells and fibroblasts to the site of tissue damage, aiding in the repair process4. Overall, it has been viewed that a transient SASP, in acute conditions (e.g. wound healing) in particular, is beneficial, whereas a chronic SASP is considered detrimental. The transient SASP consists of anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic factors that promote senescent cell clearance and tissue homeostasis and plays an important role in tissue repair, regeneration, development and tumor suppression4. In contrast, the chronic SASP comprises pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic factors that impair senescent cell clearance, thereby promoting tissue dysfunction, age-related diseases and tumor progression4. The opposing effects of transient vs. persistent SASP is further demonstrated upon cardiac injury. In mouse models of cardiac hypertrophy and heart infarction, cardiac myofibroblasts undergo senescence, resulting in less fibrosis in the short-term and improved heart function22,23. However, after cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury, the long-term oxidative stress-induced senescence in cardiomyocytes and interstitial cells promotes fibrosis and inflammation, and impairs heart function24. Hence, the balance between beneficial and detrimental effects of cell senescence very much depends on the context and the extent of senescent cell accumulation. Indeed, timely clearance of senescent cells is essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis in which the SASP plays a critical role25. Through the secretion of chemokines (e.g. CCL2), the SASP promotes the recruitment of macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, neutrophils and cytotoxic T lymphocytes, which will eliminate the senescent cells25. However, senescent cells can also interact with immune cells to avoid elimination. For example, senescent cells may express high levels of ‘don’t eat me signals’ (e.g. CD47) that impair efferocytosis by macrophages26. NK-mediated senescent cell clearance is mediated through interaction between the NKG2D receptor and its ligands expressed on the senescent cell. In some cases, senescent cancer cells can escape NK-mediated killing by increased shedding of NKG2D-ligands coordinated by matrix metalloproteinases27. Senescent dermal fibroblasts evade immune cell clearance by expressing the non-classical MHC molecule HLA-E, which interacts with the inhibitory receptor NKG2A expressed on NK and CD8+ T cells28. Overall, the immune system plays a crucial role in orchestrating the balance between elimination/clearance and accumulation of senescent cells, however, this system fails when immune cells themselves become senescent, termed ‘immunosenescence’ (vide infra).

Metabolic reprogramming in senescent cells

A key feature of senescent cells is their high metabolic activity. Senescent cells often undergo metabolic changes with a marked shift in substrate utilization for energy, likely to support their SASP production29. More than 30 years ago, it was shown that human fibroblasts undergoing replicative senescence gradually adopt a more glycolytic state30. Several other, more recent reports have corroborated these findings using more sophisticated techniques such as metabolomics or measures of mitochondrial oxygen flux and extracellular acidification. These papers describe a switch from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis during replicative senescence31,32, resulting in a reduced energetic state mirrored by reduced ATP levels33. Metabolic profiling of the extracellular metabolites of senescent cells showed overlap with aging and disease body fluid metabolomes31. Whether the metabolic switch is a driver or merely a consequence of cell senescence is less clear. It is possible that the low energetic state triggers cell senescence through activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK acts as a bioenergetic sensor and is activated when AMP:ATP and ADP:ATP ratios are increased. AMPK can induce a cell cycle arrest, and thus cell senescence by controlling p53, p21 and p1634. AMPK in turn may activate a metabolic switch to fatty acid oxidation (FAO) or may promote mitochondrial biogenesis or glucose uptake to compensate for the lower energetic state35. Indeed, other studies reported an increase in FAO and fatty acid synthesis in senescent cells. In oncogene-induced senescence, FAO is required for the secretion of pro-inflammatory SASP factors36. During replicative senescence in myoblasts, several acyl-carnitines, which serve as carriers to transport long-chain fatty acids into the mitochondria for β-oxidation, were increased, suggesting that senescent cells rely heavily on FAO37. Another study found increased levels of fatty acid synthase (FASN) in senescent mouse hepatic stellate cells and human primary fibroblasts, where inhibition of FASN prevented cell senescence and the development of a pro-inflammatory SASP38. Proteomic analysis of therapy-induced senescent cells revealed a signature of enhanced lipid metabolism including proteins involved in lipid binding, biosynthesis, degradation and storage39. Senescent cells also show accumulation of ceramide, lipid droplets and free cytosolic poly unsaturated fatty acids (PUFA’s) (reviewed in ref. 29). Free PUFA’s can be converted into oxygenated signaling molecules called oxylipins which can function as lipid-based SASP. Overall, there is increasing evidence that these lipid species play additional roles in cell senescence by acting as signaling molecules beyond their role in energy homeostasis. Furthermore, it is tempting to speculate that senescent cells may cause metabolic reprogramming in other neighboring cells through paracrine signaling, but this has not yet been investigated.

Metabolic inducers of cell senescence

Oxidative stress

Oxidative stress, either caused by overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and/or deficiency of antioxidant defenses, has been postulated as one of the primary causes of cell senescence (Fig. 1)40. ROS typically generates DNA damage such as DSB or single-strand DNA base modifications which triggers a DNA damage response (DDR)41. The DDR leads to activation of p53/p21 and a cell cycle arrest via ATM signaling pathway but may also directly induce p16. In general, most of this DNA damage is repaired and the cell can re-enter the cell cycle, however some of the DNA damage persists and will trigger premature senescence or SIPS. Nevertheless, exposure to chronic oxidative stress can also accelerate replicative senescence42. Indeed, oxidants can induce DSB at telomeric DNA, leading to telomere dysfunction while antioxidative interventions are able to reduce telomere shortening and extend replicative lifespan43. It is well-accepted that both ROS levels and oxidative damage accumulate with age and are interconnected processes that play a crucial role in age-related diseases. The age-related increase in ROS production, together with a decline in DNA repair capacity, contribute to the age-associated accumulation of DNA damage, but whether changes in antioxidant defense systems play a significant role herein remain less clear41. Indeed, although deficiencies in antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutases have been shown to induce cell senescence44,45, the studies on changes in antioxidant expression in various tissues in relation to aging is very inconsistent (reviewed in ref. 41). Besides damage to DNA, ROS can also contribute to oxidative modifications to other cellular components such as (mitochondrial) proteins and lipids. When lipids are being oxidized by free radicals, they become a major source of ROS themselves as lipid peroxides. Also lipid peroxidation increases with age and may contribute to cell senescence by exacerbating oxidative stress and promoting cellular and mitochondrial dysfunction46. The majority of ROS is produced in the mitochondria as reactive byproducts of the electron transport chain (ETC) and so it is speculated that cellular senescence is caused by an increased ROS production as result of a damaged ETC47. Notwithstanding, in some cases, ROS can be generated by NAPDH oxidases (NOX). For example, the NADPH oxidase NOX4 has been shown to induce senescence in endothelial cells48 and plays a role in oncogene-induced senescence49, suggesting that ROS can induce cell senescence independently of mitochondria. It is important to note that mitochondrial ROS produced by senescent cells can have both autocrine and paracrine effects. Mitochondrial ROS produced by senescent cells contribute to the maintenance of cellular senescence by constantly generating DNA damage, creating a positive feedback loop50. Senescent cells can also induce a DDR or telomeric damage in neighboring cells via ROS signaling51,52. Moreover, ROS can promote the generation of a SASP, either directly by activating NF-κB51, which is a major regulator of the SASP, or indirectly by inducing a ROS-dependent DDR.

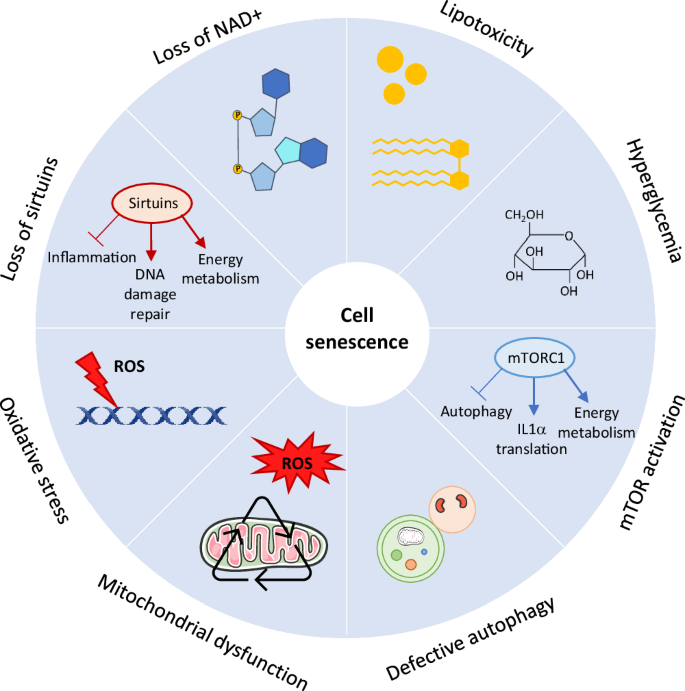

Metabolic stressors such as lipotoxicity, hyperglycemia and loss of NAD+ induce cell senescence. Loss of NAD results in reduced sirtuin activity. Sirtuins have a lot of anti-senescent effects as they promote DNA damage repair, control energy metabolism and have anti-inflammatory actions. Oxidative stress (i.e. accumulation of ROS) promotes cell senescence mostly by inducing DNA damage. Mitochondrial dysfunction accelerates senescence as a result of increased ROS generation and accumulation of oxidative mitochondrial DNA damage. In some cases, MiDAS occurs, independently of ROS, caused by a decrease in the NAD+/NADH ratio. Defective autophagy, and also defective mitophagy, can lead to cell senescence. mTOR activation promotes cell senescence by controling the SASP and mitochondrial energy metabolism whereas mTOR inhibition delays many aspects of cell senescence, which could depend on autophagy activation. mTOR mammalian target of rapamycin, NAD nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, ROS reactive oxygen species.

Mitochondrial dysfunction

As stated above, mitochondria are a major source of cellular oxidants and have been implicated in aging and age-related pathologies. Hence, it is assumed that mitochondrial dysfunction accelerates senescence as result of increased ROS generation and the concomitant accumulation of oxidative mtDNA damage (Fig. 1)53. Work by Wiley et al. defined a new form of mitochondrial dysfunction-induced cell senescence, termed MiDAS, based on a distinct senescent phenotype and secretome34. Interestingly, MiDAS displayed a modified SASP which lacked the interleukin-1 (IL-1)–NF-κB arm and was not caused by accumulation of DNA damage or oxidative stress. Instead, MiDAS was caused by a decrease in the NAD+/NADH ratio, leading to activation of AMPK, which in turn activates p53. The authors found that the growth arrest and the distinct secretome of MiDAS were p53-dependent. Moreover, the secretome of MiDAS suppresses pre-adipocyte differentiation but promotes keratinocyte differentiation, illustrating the paracrine effects of senescent cells34. Although the MiDAS phenotype was conserved in a progeroid mouse model, it is unclear how much it contributes to normal aging. During senescence, mitochondria also undergo several changes in terms of function, structure, and dynamics54. Senescent cells show increased mitochondrial mass, mitochondrial protein leak and a decreased mitochondrial membrane potential as well as decreased ATP/ADP and NAD+/NADH ratios. The mitochondria also become hyperfused and elongated, and produce large amounts of ROS and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)54. Whether the changes in mitochondrial phenotype is related to the apoptotic resistance of senescent cells is unclear. Moreover, mitophagy, the process of selective autophagic degradation of dysfunctional/damaged mitochondria, is often decreased in senescent cells, and several studies suggest that defects in mitophagy may accelerate cellular senescence (reviewed in ref. 55). The increase in mitochondrial mass in senescent cells could be the result of the impaired mitophagy but could also be explained by increased mitochondrial biogenesis56. In the aged heart, mitochondria display both morphological (e.g. swollen mitochondria, broken cristae) and functional (e.g. reduced electron transport, oxidative phosphorylation and mitophagy) changes, contributing to reduced ATP production and increased production of ROS (reviewed in ref. 57). These changes further amplify oxidative stress, inflammation, mtDNA damage, cell death and cell senescence, facilitating pathological changes in the heart (e.g. cardiac hypertrophy, cardiac dysfunction)58. Overall, mitochondrial dysfunction plays an important role in cellular senescence, not only by inducing the onset of cell senescence and production of ROS but also in the generation of the SASP, maintenance of the growth arrest and potentially the apoptotic resistance.

Hyperglycemia

Exposure to high glucose has been shown to induce cell senescence in various cell types including endothelial cells59, smooth muscle cells60 and fibroblasts61, and has been implicated in diabetes62 (Fig. 1). The underlying mechanisms are less clear but may involve ROS, nitric oxide (NO) and the arginine/arginase pathway. For example, high glucose-induced cell senescence in retinal endothelial cells is associated with reduced NO, increased oxidative stress and elevated arginase-1 expression and activity63. Inhibition of arginase, blockade of NOX2 or treatment with an NO donor, all prevented cell senescence. The same group further showed that inhibition of arginase, either genetically or pharmacologically, protects against retinal endothelial cell senescence in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice63. Accumulation of senescent endothelial cells were also found in the retinal vasculature of diabetic db/db mice64. In HUVECs, NO antagonizes senescence and increases telomerase activity while inhibition of NO by L-NAME accelerates high glucose-induced senescence65. Supplementation with arginine, a NO boosting substance and substrate of arginase-1, suppresses endothelial senescence under high glucose65. High glucose also induces senescence in fibroblasts, while glucose restriction extends replicative lifespan61. Because diabetic hyperglycemia has been shown to decrease NAD+/NADH ratios, it is plausible that high glucose levels causes MiDAS. Moreover, senescent cells accumulate in the kidneys of patients with diabetic retinopathy, and hyperglycemia has been shown to induce cellular senescence in proximal tubules in the early stage of diabetic nephropathy via a SGLT2- and p21-dependent pathway. Although not investigated in this study, it is possible that high glucose exerts its pro-senescent effects through the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Indeed, treatment of tubular epithelial cells with exogenous AGEs induces senescence which was dependent on the receptor of AGE (RAGE) and activation of ER-stress dependent p2166 and p1667 signaling. Despite the increasing links between diabetes and cell senescence, more research is needed to elucidate whether and how hyperglycemia controls the SASP, MiDAS and/or paracrine senescence.

Lipotoxicity

Lipotoxicity is caused by the accumulation of lipids, mostly fatty acids, in non-adipose cells or cellular compartments that are not capable of metabolizing or storing an excess of lipids. In the presence of ROS, excess lipids are converted into reactive lipid peroxides and oxidized lipids which promote cellular and mitochondrial dysfunction by having toxic effects on the mitochondrial DNA or proteins, or by evoking ER-stress68. Fatty acids and phospholipids are particularly sensitive to lipid peroxidation, which are known to play a role in inflammation, ER-stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, all of which can induce cell senescence (Fig. 1). Oxidation of cardiolipin for example, which is the major phospholipid in mitochondria and highly prone to lipid oxidation, leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and generation of lipid peroxides that further exacerbate oxidative stress and promote senescence46. Knockout of the enzyme that promotes cardiolipin peroxidation, prevented cell senescence and preserved mitochondrial function46. As mentioned above, lipid species can also act as signaling molecules. For example, the sphingolipids ceramide and sphingosine, have been shown to promote senescence whereas sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) had opposing effects (reviewed in ref. 69). Mechanistically, ceramide activates ceramide-activated protein phosphatases, which in turn upregulate p21, leading to a cell cycle arrest69. Much less is known however about the mechanisms by which S1P inhibits senescence. There is accumulating evidence that sphingolipids, especially ceramide, is implicated in insulin resistance and adipose tissue inflammation69. The free saturated fatty acid palmitate has been shown to induce cell senescence in human endothelial cells70 and smooth muscle cells8 which was accompanied by reduced expression of sirtuin 1 and sirtuin 6 (vide infra), respectively. Palmitic acid also induces Toll-like receptor 4 activation in macrophages, which in turn triggers senescence in vascular smooth muscle cells71. Moreover, palmitate induces pancreatic β-cell dysfunction (i.e. apoptosis and ER-stress) associated with reduced sirtuin 6 expression72 but whether this also involved cell senescence was not investigated. Overall, there is accumulating evidence that lipotoxicity induces cell senescence, but also senescence itself can make cells more vulnerable to lipotoxicity.

Endogenous regulators of cell senescence

NAD

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is one of the main energy-sensing metabolites and functions as an important co-factor in hundreds of redox reactions in all major metabolic pathways. NAD+ levels decline in multiple organs with age and low levels of NAD+ are associated with metabolic disorders73 and cell senescence74 (Fig. 1). In mice, NAD+ biosynthesis was found to be severely compromised in metabolic organs by high-fat feeding73. As such, boosting the NAD+ pool is an attractive approach to restore the energic imbalance associated with metabolic syndrome (MetS). For example, administration of the NAD precursor nicotinamide mononucleotide improves glucose intolerance and lipid profiles in high-fat diet-induced type II diabetes (T2D) mice73. The NAD precursor nicotinamide riboside has been shown to prevent high-fat diet-induced obesity75 and to oppose streptozotocin-induced diabetes in mice76. It is still unclear why NAD+ levels decline with age, though the NADase enzyme CD38, is seen as the major culprit, as its levels increase with aging77. For example, whole body CD38 deficiency attenuates angiotensin II-induced vascular remodeling and senescence78, and alleviates diabetic cardiomyopathy via activating NAD+/SIRT3/FOXO3a signaling pathways79. The CD38 inhibitor, 78c, ameliorates metabolic dysfunction in chronically aged mice by reversing age-related tissue NAD+ decline80.

Sirtuins

There is a considerable amount of evidence that the drop in intracellular NAD+ levels accelerates metabolic dysfunction and cellular senescence, in part through reducing sirtuin activity81. Sirtuins are a family of NAD+-dependent deac(et)ylase enzymes known for their role in longevity and aging82. Sirtuins regulate various important cellular processes such as cell metabolism, inflammation, cell senescence, DNA damage repair and inflammation (Fig. 1). In total, there are seven different members of the mammalian sirtuin family which share a highly conserved NAD+-binding and catalytic core domain, but differ in terms of their cellular localization, enzymatic function and substrate specificity (reviewed in ref. 82). Their need for the energy metabolite NAD+ as co-factor in the enzymatic reactions makes them key players of cellular metabolism83. Also sirtuin levels and/or activity decline with age, which can be exacerbated by cardiometabolic complications84. Hence, activation of sirtuins slows down important processes of aging, and elicits anti-senescence and anti-inflammatory effects in cardiometabolic diseases84. For example, SIRT1 and SIRT6 both protect against cell senescence in endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells in cardiovascular diseases by regulating DNA damage repair and anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory pathways (reviewed in ref. 82). They also regulate glucose metabolism84, and thus low levels of these sirtuins may underlie the metabolic changes in senescent cells. Although SIRT1 and SIRT6 have been most intensively studied in the context of cell senescence, the mitochondrial sirtuins (SIRT3, SIRT4, SIRT5) may play a crucial role in senescence-mediated metabolic dysfunction because of their importance in controlling mitochondrial homeostasis and energy metabolism.

mTOR

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is an evolutionary conserved serine–threonine kinase that senses nutrient and growth factors signals to direct cellular responses such as cell growth, apoptosis and inflammation85. There is a growing body of evidence that mTOR signaling influences longevity and aging. Inhibition of mTOR with the drug rapamycin is currently the only pharmacological treatment known to increase lifespan in different species, including mice86. Of note, the lifespan-enhancing effects of mTOR inhibitors are only linked to mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) inhibition, not mTORC2, but the mechanisms through which this occurs remains unclear. mTORC1 is involved in the regulation of many typical ‘aging hallmark’ pathways including cell senescence and autophagy87 (Fig. 1), and rapamycin has been shown to delay senescence in many cell types88,89, which in some cases are dependent on autophagy (vide infra)90,91. One way by which mTORC1 regulates cell senescence is by promoting the SASP. For example, mTOR promotes translation of IL1α which is blunted by rapamycin92. mTOR also controls the SASP by differentially regulating the translation of MAPKAPK2 which leads to improved mRNA stability of many SASP components93. Rapamycin also impairs cell-autonomous effects by regulating the cell cycle arrest in an Nrf2-dependent manner, but Nrf2 was not required for the production of the SASP94. Moreover, it has been postulated that mTOR may regulate the metabolic changes associated with cell senescence. mTORC1 controls cellular energy metabolism by increasing glycolytic flux and limiting oxidative phosphorylation85. At the same time, mTORC1 promotes mitochondrial function and stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis through PGC1α95, which could potentially explain the increase in mitochondrial mass in senescent cells.

Autophagy

Autophagy is a process in which long-lived proteins and organelles are degraded via lysosomes96. It plays an important role in protein quality control, cellular homeostasis and metabolism but its activity decreases with age96. There are several lines of evidence that basal autophagy prevents cell senescence by facilitating the removal of protein aggregates and dysfunctional mitochondria, and by promoting stemness (Fig. 1)97. Indeed, loss of autophagy has been shown to induce cell senescence in numerous cell types including endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells (reviewed in ref. 98). Also the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria due to reduced mitophagy may accelerate cellular senescence (reviewed in ref. 55). Conversely, stimulation of autophagy by mTOR inhibition suppresses senescence90,91. The inverse relationship between autophagy and cell senescence makes sense if you consider both pathways as stress response mechanisms. However, there are cases where autophagy is activated during cell senescence, in particular in oncogene-induced cell senescence99. It has been suggested that autophagy is activated in the senescent cell to maintain its autonomous and cell non-autonomous functions (reviewed in ref. 97). For example, autophagy is activated during human fibroblast senescence where it promotes the SASP through mTOR signaling99,100. Hence, although it is widely accepted that autophagy plays a protective role in aging and age-related disorders, in some cases autophagy functions as a effector mechanism in senescence99.

Cell senescence in cardiometabolic diseases

Atherosclerosis

There is a large body of evidence that cell senescence promotes the onset and progression of cardiovascular diseases including atherosclerosis (Fig. 2)101. The latter is defined as the presence of atherosclerotic plaques in the larger arteries and is responsible for nearly 30% of all deaths worldwide102. Senescent cells accumulate in atherosclerotic plaques which are found deleterious at all stages of the plaque12. Markers of cell senescence have been identified in endothelial cells103 and vascular smooth muscle cells8 in atherosclerotic plaques in experimental mice and in the vessel wall of patients with atherosclerosis. Senescence also occurs in (foamy) macrophages very early in disease12, yet macrophage senescence is more difficult to quantify because of the false positivity for both SABG and p16 markers. Previous work from Roos et al. showed that treatment with the senolytics dasatinib + quercetin (D + Q) alleviates vasomotor dysfunction and reduces senescence burden in the media of atherosclerotic mice104. D + Q therapy also reduces intimal calcification but not plaque size. Moreover, the senolytic drug ABT-263 (i.e. Bcl-2 inhibitor Navitoclax), reduces atherosclerotic plaque burden and improves features of plaque instability in mice12. Similar findings were obtained in a mouse model where senescent cells were genetically removed using a p16-driven suicide gene. Removal of p16+ cells reduced the expression of SASP factors, even in pre-existing plaques of mice that were switched to a low-fat diet12. Nevertheless, a more recent study found very variable effects of senolysis on atherosclerosis using the same genetic and pharmacological approaches10. Using bone-marrow transplantation, the authors selectively ablated bone-marrow-derived or vessel wall derived p16+ cells, or both, in atherosclerotic mice, and found no change in atherosclerosis. Instead, depletion of all p16+ cells led to increased expression of inflammatory markers (e.g. TNFα, IL18). Because p16 can also be expressed in proliferating macrophages10, the authors argue that the increased inflammation is attributed to defective clearance of dying p16+ cells by efferocytosis due to a reduced number of tissue macrophages, combined with an increased influx of circulating p16+ monocytes/macrophages10. Treatment with the senolytic drug ABT-263 reduced atherosclerosis and serum IL6 levels but other serum cytokines were unchanged. Surprisingly, no effect of ABT-263 on the expression of p16 or a range of SASP cytokine mRNAs in the vessel wall was seen, suggesting that some of the effects of ABT-263 may not be through senolysis10. Importantly, ABT-263 reduces total leukocyte, lymphocyte and platelet counts. The latter can be explained by the inhibition of Bcl-XL which platelets require for their survival. These findings suggest that ABT-263 may reduce atherosclerosis by reducing leukocytes rather than through senolysis. Indeed, ABT-263 has been shown to have strong anti-inflammatory effects that are independent of cell senescence105. A more recent study found that treatment of advanced atherosclerotic mice with ABT-263 even reduces features of plaque stability and increases mortality106, questioning the therapeutical potential of ABT-263 in atherosclerosis.

Summary of the beneficial effects (+) or side effects (−) of the senolytic drugs D + Q and ABT-263 in cardiometabolic diseases. Senolytics reduce the senescent cell burden and improve disease outcome in multiple diseases such as atherosclerosis, HFpEF, MetS, DCM and age-related cardiac remodeling. However, in some cases, immunosuppressive side effects of senolytic drugs have been described (e.g. leukocytopenia, thrombocytopenia) which challenges their translation to the clinic. BNP brain natriuretic peptide, CPC cardiac progenitor cells, DCM diabetic cardiomyopathy, D + Q dasatinib + quercetin, HFpEF heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, MetS metabolic syndrome.

HFpEF

Heart failure is a major global health care problem affecting 24 million people worldwide107. More than half of the heart failure patients develop HFpEF or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. HFpEF is also called diastolic heart failure and results from stiffening of the heart that prevent proper filling, leading to increased filling pressures, fluid retention and shortness of breath108. Metabolic comorbidities such as obesity and hypertension significantly increase the risk of developing heart failure109. This HFpEF phenotype has been defined as cardiometabolic HFpEF, a syndrome in which obesity-induced inflammation and dysregulation of immune cell responses leads to structural and functional cardiac impairment109. Also aging is an important risk factor for HFpEF110, but surprisingly limited research has been done on cell senescence in HFpEF. So far, only two studies exist and mostly focus on endothelial cell senescence (Fig. 2). Gevaert et al. showed that senescence-accelerated prone (SAMP) mice develop diastolic dysfunction which was associated with aortic endothelial cell inflammation and senescence111. However, the mice only developed HFpEF when put on a high-fat diet with 1% salt in their drinking water, suggesting that cell senescence on its own may not drive HFpEF, but may accelerate disease when additional metabolic stressors are present. Aortic vascular smooth muscle cells did not show increased senescence compared to SAMP mice on normal diet111, and also the endothelial cells and mural cells of the coronary microvasculature were not investigated. A more recent study examined cell senescence in the ZSF1 rat, a cardiometabolic model of HFpEF characterized by endothelial cell dysfunction and systemic inflammation13. The ZSF1 rats showed accumulation of senescent endothelial cells and immune cells in both the circulation and the heart when diastolic dysfunction was present. As such, it is still unclear whether senescent cells play a causal role in the development of HFpEF. Fibroblasts did not show increased markers of senescence, and whether cardiomyocytes or mural cells of the micro- and microvasculature undergo senescence was not revealed. Furthermore, the frequency of circulating senescent leukocytes correlated with clinical markers of disease severity in HFpEF patients. Treatment with ABT-263 reduced senescent cell burden, decreased circulating B-type natriuretic peptide levels, and reduced cardiac fibrosis and inflammation (i.e. reduced expression of inflammatory cytokines and reduced macrophage infiltration in the heart) in the rats. Nonetheless, ABT-263 did not affect cardiac function. Because ABT-263 also decreases the number of circulating myeloid cells, it remains to be proven that senolytic therapy (without inhibiting inflammation) has a positive effect on HFpEF.

Metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) has become the latest new health tread to the (westernized) world112. A close link exists between MetS and cardiovascular disease (CVD), the latter being the main cause of death in diabetic patients. Indeed, besides an increased risk of heart failure and diabetic cardiomyopathy, diabetic patients have a fourfold increased risk of developing atherosclerosis113. How cell senescence contributes to MetS is not yet fully understood. It has been shown that pancreatic β-cell senescence promotes T2D; high-fat diet-induced diabetic mice develop β-cell senescence which negatively correlates with insulin release114. Removal of senescent β-cells, either by depletion of p16+ cells or by treatment with ABT-263, improves glucose metabolism, and β-cell function and identity. Beneficial effects of senolysis were observed in an aging model as well as in a model of insulin resistance induced by high-fat diet (Fig. 2)115. Diabetes can also be driven by senescent cells in the adipose tissue of obese mice, which promote insulin resistance116. Indeed, removal of obesity-induced senescent cells from adipose tissue, either using the p16 suicide gene or the senolytic cocktail of D + Q, improves glucose tolerance, enhances insulin sensitivity, and lowers circulating inflammatory mediators, alleviating overall obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction116. D + Q treatment also reduces macrophage and T cell homing to abdominal adipose tissue in obese mice, suggesting that senolytics can reduce adipose tissue macrophage accumulation that is often associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome116. Moreover, microalbuminuria, renal podocyte function, and cardiac diastolic function improved with D + Q, indicating that senolytic therapy also improves diabetes-related complications116. In old mice, D + Q has been shown to attenuate adipose tissue senescence and inflammation, and ameliorate metabolic function such as glucose tolerance associated with lower hepatic gluconeogenesis117. The promising results in preclinical studies led to the first in-human trials with D + Q showing reduced senescence cell burden in adipose tissue of diabetic kidney disease patients118.

Diabetic cardiomyopathy

Diabetes is an important risk factor for CVD and is associated with changes in cardiac structure, function and metabolism, resulting in a specific cardiac phenotype called ‘diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM)’, a condition that can further evolve into heart failure119. In diabetic hearts, cardiomyocytes become more relied on fatty acids as a substrate for oxidation, which in combination with insulin resistance and reduced glucose uptake, results in altered mitochondrial energetics120. Besides changes in cell metabolism, also myocardial inflammation is thought to be a key process in DCM development. The persistent exposure to lipid and sugar excess (i.e. lipo/glucotoxicity) leads to a chronic state of low-grade inflammation, also called ‘meta-inflammation’, associated by a dysregulation of both innate and adaptive immune responses121. The relationship between T2D and cardiac senescence is very complex, and it is currently unclear whether these metabolic/inflammatory stressors contribute to cardiomyocyte senescence. The accumulation of senescent cardiomyocytes in turn may lead to cardiac dysfunction122. It has been suggested that altered mitochondrial metabolism and concomitant increase in ROS production is a pivotal inducer of myocardial senescence123. Indeed, diabetes has been shown to promote cardiac stem cell aging and heart failure due to increased ROS generation124. Cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) isolated from T2D patients show increased senescence and ROS production compared to cells from non-T2D donors125. Senescent CPCs also accumulated in a T2D mouse model and were associated with cardiac pathological remodeling125. Treatment with D + Q efficiently eliminated the senescent cells, rescued the CPC function which improved cardiac function (Fig. 2)125. This study demonstrates that T2D inhibits CPCs’ regenerative potential through the induction of cellular senescence independently of aging. Overall, we speculate that cardiac senescence is triggered both by exposure to local and systemic metabolic stressors and exposure to pro-inflammatory cells during DCM which may exacerbate any underlying cardiac dysfunction resulting from insulin resistance.

Age-related cardiac remodeling

Of all known risk factors, old age is the most important risk factor for CVD126. Accumulation of senescent cells increases with age5, but so does the incidence of heart disease. In the aged murine heart, cell senescence primarily occurs in the cardiomyocyte population122. Cardiomyocytes are particularly prone to accumulate damage due to their limited proliferation capacity. It was long thought that postmitotic cardiomyocytes cannot undergo senescence (because they do not show telomere shortening) but this concept has been refuted several years ago. Instead, during aging, cardiomyocytes undergo stress-induced senescence, associated with persistent (telomeric) DNA damage but independent of telomere length, and can be driven by mitochondrial dysfunction122. Senescent cardiomyocytes develop a non-canonical SASP phenotype which promotes myofibroblast differentiation into fibroblasts and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, all negatively affecting myocardial function122. The senescent cardiomyocyte is also characterized by a metabolic imbalance with a decline in FAO and increased dependence on glucose metabolism127. Cardiac fibrosis is an important aspect of age-associated cardiomyopathy, but the role of fibroblast senescence herein is quite controversial, and mostly depends on the animal model (infarction vs. non-infarction) used (reviewed in ref. 128). Genetic or pharmacological (i.e. ABT-623) clearance of senescent cells in aged mice reduces cardiomyocyte senescence and alleviates the detrimental effects on cardiac aging, including myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis (Fig. 2)122. Also treatment with D + Q improves cardiac function and carotid vascular reactivity already 5 days after a single dose in aged mice129. Moreover, elimination of senescent cells using ABT-263 improves myocardial remodeling and diastolic function as well as overall survival following myocardial infarction130. When senescent cardiomyocytes accumulate with age, they would further compromise cardiac function, promote chronic inflammation, and eventually lead to cardiomyocyte loss and impaired cardiac function. Indeed, 50% of CPCs isolated from human subjects >70 years old were found senescent, and thus unable to replicate or restore cardiac function following transplantation into the infarcted heart131. Through their SASP, aged-senescent CPCs induce paracrine senescence in healthy CPCs which was abrogated by treatment with D + Q. In vivo, D + Q treatment or removal of p16+ cells, activate resident CPCs and increase the number of proliferating cardiomyocytes in the aged heart, suggesting that senolytic therapy may alleviate cardiac deterioration with aging and restore the regenerative capacity of the heart131.

Therapeutic interventions to target cell senescence

Senolytics

Researchers are actively exploring ways to manipulate cellular senescence to mitigate its negative effects. One approach is to remove senescent cells using so-called senolytic drugs (Fig. 3). These drugs eliminate senescent cells by selectively inducing apoptosis. This is based on the observation that many senescent cells upregulate one or more anti-apoptotic pathways129. Senolytic therapy has shown promise in reducing age-related pathologies in various preclinical models and are currently being tested in many clinical trials in different diseases (reviewed in ref. 132). The most widely used senolytics are those that target the Bcl-2 family members such as ABT-263, also known as Navitoclax. ABT-263 induces apoptosis in senescent cells in vitro and in vivo by inhibiting the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and Bcl-W129. ABT-263 successfully reduces senescent cell burden in atherosclerotic plaques, in aged hearts and upon HFpEF in rodents (Fig. 2). Other popular senolytics are dasatinib (D) and quercetin (Q), which have a rather mild senolytic activity but in combination (D + Q) have been proven highly effective in removing senescent cells in various cell types and in vivo. Dasatinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor and has many receptor targets including ephrins. Inhibition of ephrin promotes apoptosis in senescent cells by acting on Bcl-XL, PI3K, p21 and plasminogen activator inhibitors (PAIs)129. Quercetin is a naturally occurring flavonoid and acts on many pro-survival proteins including PI3K and PAIs. However, the sensitivity for D and Q might be cell type-dependent. For example, D, but not Q, favors apoptosis of senescent human fat progenitor cells while Q preferentially induces apoptosis in human endothelial cells and bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells129. D + Q successfully reduces senescent cell burden in adipose tissues of mice with MetS and DCM (Fig. 2). Moreover, a recent study from Islam et al. showed that D + Q attenuates adipose tissue inflammation by alleviating immune cell recruitment, and ameliorates systemic metabolic function (e.g. glucose tolerance, plasma cholesterol levels) in aged mice117. D + Q are also the first senolytics used in clinical trials for reducing senescent cell burden in adipose tissue of diabetic kidney disease patients118. Fisetin, another flavonoid, has recently been shown to ameliorate endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness in old mice by reducing cell senescence133, and is currently being tested in a clinical trial for peripheral artery disease (NCT06399809).

There are four possible strategies to eliminate senescent cells: (1) Senolytics. These drugs kill senescent cells by selectively inducing apoptosis. (2) Senostatics. These drugs do not remove senescent cells but will limit the detrimental effects of senescent cells by inhibiting the SASP by targeting the signaling pathways (e.g. NF-kB, JAK–STAT, mTOR, p38 MAPK) involved in SASP production or release. (3) Senescence bypass or reprogramming. The aim here is to bypass the irreversible growth arrest (e.g. by expressing ∆133p53α isoform of p53) without evoking genetic instability, or to promote reprogramming by expression of the reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc. (4) Immunosurveillance. Immune cell-mediated senescent cell clearance can be promoted using vaccines or CAR T (or NK CAR) cell therapy against senescence-specific antigens, or by triggering NK-mediated ADCC. ADCC antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, CAR T cell chimeric antigen receptor T cell, NK natural killer cells, SASP senescence-associated secretory phenotype.

Despite these promising results, some questions concerning the long-term effects and safety of senolytic therapy remain largely unanswered. For example, the use of ABT-263 in humans is limited due to its dose-dependent platelet toxicity134. However, He et al. tried to solve this issue using proteolysis-targeting chimera technology to convert ABT-263 into PZ15227. Compared to ABT263, PZ15227 is less toxic to platelets, but at least as potent against senescent cells135. Similar strategies might be useful to improve the safety profile of other senolytic agents. Up till now, mostly D + Q, Q alone or fisetin, have been used in clinical trials because of their short half-lives, rapid elimination, and good safety profile (reviewed in ref. 132). Q for example, is currently being tested in a phase II clinical trial in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery136. Compared to the flavonoids which are well-tolerated, there are few cases where D was reported to exert cardiotoxic effects137. The underlying mechanism is largely unknown but may involve changes in the mitochondrial membrane potential. Moreover, more than 40% of patients that receive D treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia, develop thrombocytopenia138. It is unclear why, but D is thought to act on some key kinases involved in platelet homeostasis. Other remaining question concerns the dosing. It has been suggested that senolytic therapy can be administrated intermittently, e.g. once a month, and would be as effective as continuous treatment to reduce senescence burden139. This is based on the observation that only 30% of the senescent cells need to be removed to have beneficial effects in preclinical studies and that it takes several weeks for senescent cells to reaccumulate after senolytic treatment118,139. One benefit of this ‘hit-and-run’ approach is that it would severely reduce the risk of side effects. A more targeted approach to reduce systemic effects is currently under development, such as senolytic vaccination against senescent epitopes140. It is also important to note that senolytic drugs may ameliorate disease through effects that are independent of senolysis, for example by suppressing inflammation (e.g. ABT-263) or reducing ROS (e.g. flavonoids).

Senostatics

Because the SASP is thought to drive senescence-mediated tissue damage and age-related pathologies, therapies that reduce the SASP rather than eliminating senescent cells are being actively explored. These drugs are called senostatics, or senomorphics, and inhibit the SASP by targeting the signaling pathways (e.g. NF-κB, JAK–STAT, mTOR, p38 MAPK) involved in the production or release of the SASP (reviewed in ref. 141) (Fig. 3). Senostatic therapy has a few advantages over senolytic therapy. One advantage is that these drugs do not kill the senescent cells (which could trigger impaired efferocytosis or apoptosis-induced cytokine release), instead, they will lower the impact on the micro-environment by inhibiting the autocrine and paracrine effects of the SASP. In this way, senostatic therapy will halt senescent cell accumulation and spreading. Because these drugs do not remove senescent cells, including those that are beneficial in some cases (e.g. wound healing), one could argue that senostatic drugs are safer to use compared to senolytics. Nevertheless, many senostatic drugs have off-target effects, and suppress the immune system, which can increase the risk for infections. As such, they are less popular and have not been tested yet in clinical trials as anti-senescence therapy. Most well-studied senostatics are rapamycin, metformin and resveratrol. Rapamycin treatment has been shown to increase lifespan and health span in middle-aged mice142. The senostatic and anti-aging effects of rapamycin are largely related to its inhibition of mTOR signaling. Another potential mechanism of action involves inhibition of IL1α translation92. However, several side effects for rapamycin have been reported such as impaired glucose tolerance and hyperlipidemia, nephrotoxicity, impaired wound healing and susceptibility to infections143. Metformin is the most common treatment for T2D and has potential as a treatment for CVD irrespective of the diabetes status144. In fact, metformin is now being tested for its anti-aging effects in a large clinical trial called TAME (Targeting Aging by Metformin)145. Metformin downregulates the expression of several senescence and SASP factors in various cell types such as endothelial cells, fibroblasts and adipocytes146,147,148 and increases lifespan and health span in different organisms including mice149. The mechanisms of actions include inhibition of NF-κB activation147 and activation of AMPK148 but may also involve SIRT1 activation, down-regulation of insulin/IGF-1 signaling, inhibition of mTOR, attenuation of oxidative damage, improvement of mitochondrial function and stimulation of autophagy. The pleiotropic effects of metformin make it difficult to dissect how much of its therapeutic effect depends on its anti-senescence properties. Resveratrol has been known for its antioxidative and anti-aging properties for decades. For example, it prevents cellular senescence of endothelial progenitor cells by increasing telomerase activity through the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway150 and suppresses age-induced cytokine secretion and mitochondrial ROS production by inhibiting NF-κB and upregulating Nrf2 pathways in vascular smooth muscle cells from aged non-human primates151. Resveratrol also protects endothelial cells from cell senescence via SIRT1 activation152, augmenting mitochondrial biogenesis153 or upregulation of autophagy154. Nevertheless, resveratrol failed to increase lifespan in a number of studies in flies and mice (reviewed in ref. 155). It is been suggested that resveratrol needs an extra ‘metabolic hit’ as it only extends lifespan of mice on a high-fat, but not on a standard, diet155. Besides resveratrol, many other natural products, mostly polyphenols, exert antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, and thus may have the potential to suppress senescence (reviewed in ref. 141). Other senostatics include small molecule inhibitors that block pro-inflammatory signaling molecules such as NF-κB, p38 MAPK or JAK–STAT (reviewed in ref. 141). The JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib for example, known as an anti-cancer drug, has been shown to suppress the SASP, to reduce systemic inflammation and frailty, and to improve metabolic function in old mice156. Also the statins, the first choice of treatment for patients with hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis, have been reported to exert anti-senescent effects. For example, statins inhibit endothelial cell senescence in an Akt-dependent manner by upregulating endothelial nitric oxide synthase, SIRT1, and the antioxidant enzyme catalase157. Statins also protect against telomere shortening in blood peripheral mononuclear cells by increasing telomerase activity158 and accelerate DNA damage repair in vascular smooth muscle cells159, thereby delaying cell senescence. Many of these drugs have pleiotropic effects and exert its therapeutic effect independent of senescence. As such, there is a need for new, more specific anti-SASP therapies.

Senescent cell bypassing and reprogramming

Bypassing the growth arrest in senescent cells can be achieved by influencing the expression of cell cycle regulators (e.g. CDK4/6) or tumor suppressor genes (e.g. p53)160 but the danger of this approach lies in promoting uncontrolled growth (Fig. 3). Inactivation of p53 promotes self-renewal of human-induced pluripotent stems cells by inhibiting cellular senescence, but at the same time also inhibits the elimination of damaged cells and impairs genome stability by blocking apoptosis and DNA damage repair, respectively161. However, selective inhibition of p53 activity by overexpressing the ∆133p53α isoform only promotes self-renewal without impairing genome stability161. Upon T cell replicative senescence, overexpression of ∆133p53α rescues the senescent phenotype of CD8+ T cells and restores cell proliferation162. Another emerging approach is the in vivo partial reprogramming by expression of the reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc (also known as Yamanaka factors). Short-term cyclic expression of these factors partially rescues the degeneration of vascular smooth muscle cells and bradycardia in a premature aging mouse model associated with overall improvement of cellular and physiological hallmarks of aging and prolongation of lifespan163. Compared to short-term reprogramming, long-term reprogramming promotes tissue rejuvenation in physiologically aged mice and was found to be more effective in delaying the aging phenotype164.

Immunosurveillance

With aging, there is an increased dysfunction of both innate and adaptive immune responses, defined as ‘immunosenescence’. To date, it is not completely clear whether aging-induced immune cell dysfunction permits senescent cell accumulation because their capacity to clear senescent cells is exceeded or because their clearance function is impaired due to inhibitory factors released by senescence cells. Indeed, the ability to respond to antigens and to phagocytose cell is impaired in aged immune cells25. Hence, therapies that enhance the immune cell-mediated clearance of senescent cells could reduce senescent cell burden and associated diseases25. Such immunotherapies include (1) vaccines against senescent epitopes to facilitate elimination of senescent cells by eliciting an immune cell response, (2) chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy directed against senescence-specific surface antigens, or (3) use of antibodies targeting senescence cells for removal by NK cells (Fig. 3). All these techniques require the identification of a senescence-specific protein on the cell surface that is lowly expressed on healthy tissue or does not play a critical role in normal physiology. For example, Suda et al. identified glycoprotein nonmetastatic melanoma protein B (GPNMB) to be enriched on the cell surface of senescent endothelial cells165. Treating mice with a peptide vaccine against GPNMB improves normal and pathological phenotypes associated with aging, and extends the lifespan of male progeroid mice165. The vaccine reduces atherosclerotic plaque burden and metabolic dysfunction such as glucose intolerance in mouse models of obesity and atherosclerosis. The senolytic effects are likely mediated by antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC)-dependent elimination of GPNMB+ cells, although other mechanisms might also be involved. Yoshida et al. developed a CD153 targeting vaccine shown to prevent the accumulation of CD153+ senescent T cells in visceral adipose tissue in mice on a high-fat diet, which was associated with improved glucose tolerance166. The vaccine prevents senescent cell accumulation by inducing apoptosis through complement-dependent cytotoxicity166. CAR T cell therapy uses autologous cells of the patient that are being genetically modified ex vivo to target a specific antigen when infused back into the patient. Amor et al. recently identified the urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) as a broad cell surface protein marker on senescent cells and demonstrated that uPAR-specific CAR T cells efficiently ablates senescent cells in a lung cancer and liver fibrosis model167. Anti-uPAR CAR T cell therapy also improves exercise capacity during physiological aging, and it ameliorates metabolic dysfunction in mice on a high-fat diet168. One advantage of CAR-T cells is their ability to induce a sustained response after a short-term treatment. Since NK cells are the natural killers of senescent cells, using NK cells might be another efficient strategy to eliminate senescent cells. One advantage of NK-CAR cells over CAR-T cells is that NK cells retain their ability to recognize target cells through their native receptors, in case the senescent cell downregulates the CAR target antigen. Another approach involves NK-mediated ADCC. For example, senescent human fibroblasts express high levels of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) on their surface, and can be killed by NK using anti-DPP4 antibodies through ADCC169. Overall, these techniques offer a promising strategy to combat age-related diseases by targeting senescence-specific antigens and inducing immune responses but their efficacy in human clinical trials still need to be proven.

Future perspectives

Senolytics have been postulated as the ‘holy grail’ against age-related disorders. The list of preclinical studies showing beneficial effects with senolytics is long, yet concerns remain in terms of dosing, specificity and safety in humans. Indeed, many senolytics exert off-target effects—often independent of their senolytic action—and the immunosuppressive actions of some senolytics might evoke an increased risk of infections. Moreover, elimination of all senescent cells is not always beneficial and could even be dangerous in cases where they are needed such as during wound healing. For example, elimination of senescent endothelial cells using ABT-263 has been shown to worsen pulmonary hypertension in mice170 and genetic removal of p16-expressing liver sinusoidal endothelial cells induces liver fibrosis171. It also remains unclear what happens with the senescent cells that are dead. Are they cleared properly from the tissue by efferocytosis and is there a risk for apoptosis-induced cytokine release? Furthermore, it should be noted that not all senescent cells are resistant to apoptosis, and so then another approach is required. In this case, senostatics could be a more suitable strategy. However, most currently available senostatics exert many (off-target) effects independently of senescence. Hence, there is a need for new, more specific anti-SASP therapies. When developing senostatics, the varying composition and dynamics of the SASP should be considered. Also selectivity and specificity is crucial to avoid targeting non-senescence SASP-like factors. Senostatics should preferentially target the persistent and tissue-destructive SASP which might have a higher therapeutic potential but less off-target effects. Besides the use of senolytics and senostatics, we should also explore other possibilities to eliminate senescent cells, for example, by promoting immune cell-mediated senescent cell clearance or inducing senescent cell reprogramming. The identification of specific senescent cell surface proteins will facilitate the development of strategies to enhance their clearance. Vaccine-based and CAR T cell therapies against senescence-specific antigens are good examples of such innovative anti-senescence approaches140. However, these techniques are challenged by the fact that immune cells themselves also undergo senescence with age, which impairs their ability to respond to antigens and to phagocytose cells25. Indeed, immunosenescence may limit vaccine response and T-cell memory in older individuals172. Another interesting approach to promote rejuvenation is based on the concept of removing circulating factors from the blood that promote ‘inflammaging’ (reviewed in ref. 173). This new strategy is called plasma dilution whereby half of old human blood is replaced by (5%) albumin to dilute age-increased systemic factors. This technique has been shown to ameliorate oxidative DNA damage and cell senescence, to promote a more youthful profile of myeloid/lymphoid markers in circulating cells and a global shift to a younger systemic proteome174. Efforts are underway to translate these findings into new anti-aging therapies. Overall, the exciting results from preclinical studies with both the classical senolytics and newly developed anti-senescence (immune)therapies pave the way for future drug research into more specific and safer anti-senescent drugs and translation into therapy for human disease.

Conclusion

Cell senescence is a multifaceted biological process that has extensive implications for both normal physiological functions and age-related (cardiometabolic) diseases. Although there is a growing body of evidence that cell senescence promotes the onset and/or progression of many cardiometabolic diseases, much is still unknown. For example, the frequency of senescent cells in diseased tissue is not known, largely due to the fact that we lack a specific (in vivo) marker for cell senescence. Understanding the paracrine effects of cell senescence is essential for grasping the broader implications of senescent cell spreading in disease, and how metabolic stressors affect the SASP and paracrine senescence is largely unknown. Moreover, the role of cell senescence in HFpEF and diabetic cardiomyopathy, in contrast to atherosclerosis, is little investigated. It is presumed that the pathological impact of cell senescence is (at least partly) caused by the chronic and pro-inflammatory nature of the SASP, yet this remains to be fully proven. A deeper understanding of cell senescence will lead to innovative strategies for treating age-related cardiometabolic diseases and promoting healthy aging. With age, the number of senescent cells in a person’s body increases, but to date it is unclear whether this is due to an increase in senescent cell generation and/or whether it reflects the reduced ability of the aged immune system to clear these cells. Knowing this will further help us define effective anti-senescence strategies.

Responses