The impact of blood pressure lowering agents on the risk of worsening frailty among patients with diabetes mellitus: a cohort study

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is of substantial importance globally, causing excessive morbidity and mortality associated with poor glycemic control and diabetic complications. The estimated health expenditure related to DM exceeds 300 billion annually1, and DM is now the eighth largest source of disease burden worldwide according to the Global Burden of Disease registry2. Most adverse outcomes associated with DM result from complications including nephropathy, retinopathy, and vascular injuries. Frailty is an occult diabetes-related complication, which describes the multi-dimensional degeneration affecting one’s body, mind, and/or social condition associated with an increased susceptibility to harmful insults from external sources3. Among 123,172 adults with incident DM, Huang et al. discovered that 20.8% already had frailty, among whom 37% were of moderate to severe degree4. Mild frailty also increases the risk of type 2 DM5,6. DM therefore carries a bi-directional relationship with frailty from the epidemiological and pathobiological perspectives.

Risk factors for frailty range widely. A recent systematic review concluded that older age, female, lower body mass index (BMI), and specific morbidities (DM and cardiac disorders) increased the probability of developing frailty7. Modifiable risk factors for frailty also exist, including BMI, morbidity management status, higher blood pressure (BP), low-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride levels, all of which are findings with a high prevalence in patients with DM8,9. However, existing studies mostly examine frailty risk factors in older adults or those with other morbidities, less frequently in patients with DM, except for hypoglycemic episodes and poor glycemic control10. Hence, a research gap exists accordingly.

Apart from the insufficient understanding of frailty risk factors, even fewer studies address predisposing factors for frailty progression, or worsening frailty. A recent article emphasized the importance of unearthing why and how patients exhibit worsening frailty11. Multimorbidity can potentially drive frailty progression regardless of baseline frailty status, but unexplored factors remain. It is foreseeable that a large proportion of patients with DM will experience worsening frailty over time, and prompt mitigation measures are needed to ameliorate this trend. How we manage DM patients’ morbidities may influence the probability of frailty progression. A previous study demonstrated that differences in glycemic control strategies played a significant role in modifying the risk of worsening frailty12. Another recent study reveals inter-class differences existed with regard to the effect of BP-lowering agents on pre-frailty13, but their findings are indirect. Moreover, existing reports mostly utilize physical measurements as the outcome assessment tool instead of an index-cased one14. We hypothesized that BP-lowering agents might affect the risk of worsening frailty in patients with type 2 DM. We aimed to answer this question through assembling a retrospective DM cohort to examine whether BP-lowering agents influenced frailty trajectory, and whether class-specific influences existed.

Results

Study population characteristics

In total, 82,208 adults with DM were retrieved from the integrated medical database (iMD) of National Taiwan University Hospital, of whom 41,440 patients with type 2 DM without pre-specified exclusion criteria were identified for assembling the current study cohort (Fig. 1). Their mean age was 64.1 years (46.3% female), and the most common comorbidity was hypertension (62.6%), followed by hyperlipidemia (45.6%) and prior acute coronary syndrome (24.6%) (Table 1). Approximately one-fourth of the patients received angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) (28.0%), antiplatelet agents (24.4%), or antilipidemics (23.1%) at baseline. ARBs were the most common class of BP-lowering drugs used, followed by calcium channel blockers (CCBs) and β-blocker. For glucose-lowering regimens, patients most commonly received a combination of oral glucose-lowering drugs (oGLDs) (27.9%), followed by monotherapy with oGLDs (24.1%) and insulin (4.8%) (Table 1). The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) was low, and patients’ estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 74.2 ± 26.2 mL/min/1.73 m2. At baseline, fatigue was the most prevalent FRAIL item (12.4%) (Table 1).

DM, diabetes mellitus; NTUH, National Taiwan University Hospital.

Frailty test validity reassurance

We first evaluated the validity of our frailty assessment results, through examining the correlation between results of our modified FRAIL scale and those using multimorbidity frail index established by others15,16. Results of our FRAIL scale correlated significantly with those of another multimorbidity frail index (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table S1). Increasing numbers of positive FRAIL items paralleled higher scores of the multimorbidity frail index in our population, supporting the validity of our approach.

Comparison of baseline features between patients without and with outcomes

After a median 4.09 years of follow-up, 11,371 (27.4%) patients with DM developed worsening frailty. Those with worsening frailty had a more advanced age (p < 0.01), lower BMI (p < 0.01), and a significantly higher prevalence of nearly all comorbidities, except for cerebrovascular disease (p = 0.21), cancer (p = 0.82), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (p = 0.27), compared to those without (Table 1). Charlson comorbidity index and the total number of BP-lowering agent used were higher among patients with worsening frailty than those without. During follow-up, the proportion of patients receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or ARBs was 12.1% and 59.6%, respectively (Table 1). Patients with worsening frailty were more likely to receive most classes of BP-lowering agents (except β-blockers) and anti-platelet agents (p < 0.01) but less likely to receive anti-lipidemic agents (p < 0.01) and anti-inflammatory agents (p < 0.01) than those without. Patients with worsening frailty had significantly higher fasting glucose (p < 0.01), glycated hemoglobin (p < 0.01), total cholesterol (p < 0.01), and triglyceride (p < 0.01) levels but lower eGFR (p < 0.01) than those without worsening frailty (Table 1). Age at baseline was significantly higher among individual BP-lowering agent users than non-users (Table 2). There were no significant differences regarding Charlson comorbidity index between ACEI, ARB, and β-blocker users and non-users, while the index was higher among CCB, diuretic and α-blocker users than non-users (Table 2). All six BP-lowering agent class users had significantly higher total numbers of BP-lowering agent use compared to individual agent non-users (Table 2).

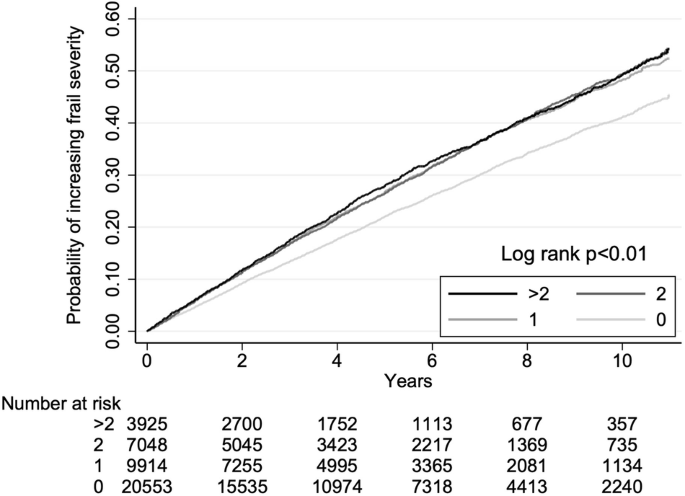

BP lowering agent counts and classes influence the risk of frailty worsening

Kaplan–Meier event-free analyses revealed that users of one, two, and more than two classes of BP-lowering agents had a significantly higher risk of worsening frailty than non-users (Fig. 2). Upon univariate analysis, Cox proportional regression showed that patients with DM had a significantly and stepwise higher risk of worsening frailty with increasing classes of BP-lowering agent use (hazard ratio (HR) for 1, 2, and >2 classes were 1.25, 1.27, and 1.29, respectively) (Table 3). After adjusting for demographic profiles, comorbidities, non-BP-lowering medications, and laboratory data, only those receiving monotherapy of BP-lowering agents had a significantly higher risk of worsening frailty than those without (HR 1.10, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.15), whereas those receiving ≧2 classes of agents did not (Model 2; Table 3). This suggests that the class of BP-lowering agents may alter the risk of frailty worsening.

Kaplan-Meier event-free curves according to blood pressure-lowering agent use status (0, none; 1, 2, and >2 classes of medication users).

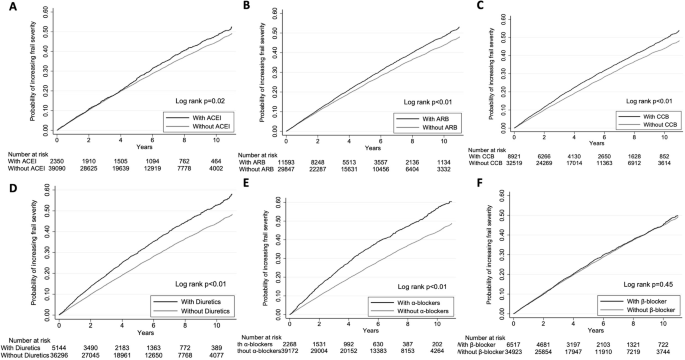

We then examined which class of BP-lowering agents influenced risk among these patients with type 2 DM. Kaplan–Meier event-free analyses showed that patients receiving ACEIs (Fig. 3A), ARBs (Fig. 3B), CCBs (Fig. 3C), diuretics (Fig. 3D) or α-blockers (Fig. 3E) had significantly higher risk of worsening frailty than those who did not. However, the risk did not differ between β-blocker users and non-users (Fig. 3F). Comparisons of clinical features between users and non-users are shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Tables (for ACEI, ARB, CCB, diuretic, α-blocker, and β-blocker, refer to Supplementary Tables S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, and S7, respectively). Univariate analysis disclosed ACEI (HR 1.09), ARB (HR 1.12), CCB (HR 1.16), diuretic (HR 1.33) and α-blocker (HR 1.46) users had a significantly higher risk than the respective non-users (Table 4). Cox proportional hazard regression analyses adjusting for demographic profiles, comorbidities, and non-BP-lowering medications revealed that only diuretic (HR 1.12, 95% CI 1.06–1.19) and α-blocker (HR 1.14, 95% CI 1.06–1.23) users had a significantly higher risk of worsening frailty than non-users, whereas the risk was significantly lower among β-blocker users (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88–0.98) (Model 1; Table 4). These associations remained unchanged after further adjustments for laboratory data (Model 2; Table 4). When mortality was considered a competing event, diuretic (HR 1.10, 95% CI 1.03–1.16) and α-blocker (HR 1.13, 95% CI 1.04–1.22) users still had a significantly higher risk of worsening frailty than non-users, whereas β-blocker users had a lower risk (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.87–0.97) (Table 4). After adjustment for Charlson comorbidity index and the total number of BP-lowering agents, the results remained essentially the same (Model 3; Table 4).

A, ACEI; B, ARB; C, CCB; D, diuretics; E, α-blocker; F, β-blocker. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses focused on influences of treatment durations showed that a longer duration of β-blocker use (HR 0.88 and 0.91 for users of 90–179 and ≥180 days, 95% CI 0.8–0.97 and 0.85–0.97, respectively) was independently associated with a lower risk of worsening frailty (Model 2; Table 5). Users of higher β-blocker dosage also exhibited a progressively lower risk of worsening frailty (HR 0.86 and 0.84 for 2nd and 3rd dosing quartiles users, 95% CI 0.77–0.95 and 0.77–0.93, respectively) (Model 2; Table 5). The longest duration of diuretic use (HR 1.10 for users of ≥180 days, 95% CI 1.03–1.18) and the highest dosing quartile diuretic users (HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.06–1.27) had a significantly higher risk of worsening frailty (Model 2; Table 5). The 3rd dosing quartile of α-blocker users also had significantly higher risk of worsening frailty than non-users (HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.04–1.38) (Model 2; Table 5). When the definition of BP-lowering agents use was limited to consecutive use within the time frame, diuretic (HR 1.12, 95% CI 1.06–1.19) and α-blocker (HR 1.14, 95% CI 1.06–1.23) users still had a significantly higher risk of worsening frailty than non-users, whereas β-blocker users remained at a lower risk (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88–0.98) (Supplementary Table S8).

Discussion

This study focused on the influence of BP-lowering agents on the risk of worsening frailty in a large group of patients with type 2 DM. After accounting for an extensive array of confounders, we showed that individual class of BP-lowering agents altered such risk; β-blockers use was associated with mildly decreased risk of worsening frailty by 8%, whereas diuretics and α-blockers use were associated with a significantly increased risk by 6% and 8%, respectively. A dose and duration relationship could be observed for β-blockers and diuretics, whereas that between α-blocker use and the risk of worsening frailty was less evident. Our findings revealed the potential effects of BP-lowering agents on an important yet underexplored endpoint in patients with DM. Therefore, it is prudent to carefully choose BP-lowering agents in this population, weighing the pros and cons of each class.

Existing literature has established the therapeutic effects of BP-lowering agents in reducing end-organ damage caused by hypertension. In the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) and its follow-up analyses, researchers showed that strict BP control resulted in decreased major cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality17, accompanied by cognitive benefits18 and potentially functional implications. Subsequently, it has been shown that the class of BP-lowering agents plays an instrumental role in modifying cardiovascular outcomes, independent of the degree of BP reduction19. Moreover, heterogeneity exists in the therapeutic effects of these medications. For example, in the SPRINT trial, ACEI, ARB, and thiazide-type diuretic use were associated with less myocardial infarction and heart failure events, respectively, whereas others did not20. Genetic proxies of CCB use were shown to increase the risk of intracranial aneurysms and subarachnoid hemorrhages among hypertensive patients, but other classes of BP-lowering agents did not21. A Cochrane meta-analysis concluded that each class of BP-lowering agent conferred diverse influences on the risk of different cardiovascular events22. However, current reports rarely examine the influences of BP-lowering agents on functional changes. Therefore, our findings enrich the literature by linking specific BP-lowering agent classes with softer outcomes such as worsening frailty.

We showed that β-blocker use independently correlated with a lower risk of worsening frailty (Table 4). β-blockers are an important class of pharmaceutics with indications of anti-hypertension, anti-arrhythmia, and heart failure management. Studies rarely link β-blocker use to altering the probability or the severity of geriatric phenotypes, especially frailty. It is plausible that β-blockers may influence the probability of worsening frailty, through improving cardiovascular fitness and attenuating the progression of heart failure or arrhythmia, both of which can be drivers for progressive frailty6. Such influence potentially becomes more obvious in patients with DM at higher cardiovascular risk. Moreover, a recent study analyzing the influences of medications on biologic aging showed that genetically proxied β-blocker administration exhibited beneficial effects on retarding aging23. BP-lowering agents also influence bone-related health outcomes in experimental and clinical studies24. Finally, prior reports supported that β-blocker use was associated with a significantly decreased fracture risk25, and osteoporosis with the associated fractures is a vital contributor to frailty development and progression26. This may result from their osteoclast-inhibitory activities through selective β-receptor blockade. Nonetheless, β-blocker use in patients with DM still carries the untoward effect of masking hypoglycemia. In light of these findings, our observation of the positive frailty trajectory-influencing effects from β-blocker should be weighed against its negative effects in other aspects, and it takes a wise physician to make an individualized choice when managing hypertensive patients with DM.

We also found that diuretics and potentially α-blockers might augment the risk of worsening frailty in patients with DM (Table 4). Although thiazide diuretics reduce cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients20, loop diuretics have not consistently demonstrated such benefits. In addition, loop diuretics may increase urinary calcium excretion, leading to higher parathyroid hormone secretion and accelerated negative bone mass balances24. Moreover, diuretics can trigger nocturia, impair sleep quality, cause hypovolemia, and predispose users to inadvertent fall episodes, a predecessor of subsequent frailty. Another plausible machinery responsible for diuretic-associated risk of worsening frailty can be the occult development of dysnatremia and dyskalemia, whose severity frequently parallels that of frailty27. In contrast, α-blockers carry the well-known adverse effect of orthostatic hypotension, which has recently been attributed as a component of “vascular frailty”28. Nonetheless, the influence exerted by α-blockers became less prominent during dose and duration analyses (Table 5); this might result from the lower number of observed outcomes in higher dose and longer duration users. Other plausible explanations for the adverse frailty progression-related effects were observed for these classes of BP-lowering agents.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. The number of cases in our cohort was large enough to permit adjustment for multiple confounders, including demographic profiles, physical parameters, comorbidities, medications, and laboratory panels. The dose- and duration-responsive relationship between the studied drugs and the outcomes supported the validity of the results. We used a standardized approach to identify frailty, the FRAIL scale, and ascertained medication usage based on criteria adopted previously12. Moreover, the results of our modified FRAIL scale showed an intimate correlation with findings using other frailty-assessing instruments (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, demographic features of our patients were similar to those of the general population in Taiwan, supporting the applicability of our findings. Varying the definitions of BP-lowering agent use in this study did not alter our findings. We also adjusted for non-hypertension indications for each class, such as β-blocker with heart failure and α-blocker with prostatic hyperplasia. Finally, we evaluated whether these six BP-lowering agents influenced baseline frailty status, which potentially influenced the associations between specific BP-lowering agent use and risk of worsening frailty. None of these agents exhibit independent correlation with baseline frailty (Supplementary Table S9), lending support to the validity of our findings. However, this study has some limitations. First, our study was retrospective in nature, and there might be other unmeasured factors that posed influences. Second, each frailty-identifying tool has its own sensitivity and specificity, and it is possible that some patients with worsening frailty were not identified. Second, our patients were ethnically homogeneous, and extrapolating our findings to patients with DM of other ethnicities may not be feasible. Thirdly, the prescription patterns of BP-lowering agents may differ between local physicians and those of other countries, as reported previously29. Nonetheless, we believe the effects remains consistent. Finally, there may be residual imbalances in frailty-modifying variables between patients with and without worsening frailty. Nonetheless, we believe that the size of our cohort negates this concern.

In conclusion, we investigated the effects of BP-lowering agents on the risk of frailty worsening in a large cohort of patients with type 2 DM. We discovered that β-blocker use was associated with lower worsening frailty risk, whereas diuretics or α-blocker users exhibited the contrary. This relationship was independent of age, sex, comorbidities, other medications, glycemic control, nutritional status, and renal function. Our findings suggest that to ameliorate the risk of worsening frailty in patients with DM, optimization of antihypertensive regimens will likely be helpful. It would also be prudent to weigh the advantages and disadvantages of initiating a specific class of BP-lowering agents in patients with DM, considering the effects of frailty.

Methods

Ethical statement

The protocol for this study, which belonged to a comprehensive study focusing on the epidemiology and distinct medication effects of patients with DM, was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Taiwan University Hospital. Informed consent was deemed unnecessary by the Institutional Review Board owing to the retrospective nature of this study and data anonymization prior to retrieval. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The procedure of this study

The iMD of National Taiwan University Hospital and its affiliated branches served as the substrate for this study. We retrospectively identified patients older than 40 years old with DM between 2008 and 2016 from the iMD, followed by application of the exclusion criteria. The diagnosis of DM was made based on the presence of at least one DM diagnosed by physicians in any clinical setting (outpatient, inpatient, or emergency care), having a fasting glucose level higher than 126 mg/dL, or a glycated hemoglobin level >6.5% according to the American Diabetes Association guidance30. Exclusion criteria included those with type 1 DM, those who did not receive follow-up, those with missing laboratory data, and those with established frailty, since further worsening of frailty is difficult to be determined in these frail patients. The remaining patients were included in the study cohort. The index date was defined according to the date when the DM diagnosis was satisfied. This approach was adopted to maximize the duration of follow-up and also to illustrate the local BP-lowering treatment patterns. Follow-up was discontinued after December 31st, 2017, death, or the development of pre-specified outcomes as described below.

We systematically recorded the patients’ demographic profiles (age, sex, and BMI), comorbidity status, concurrent medication regimens at baseline, and laboratory panel results within one year after the index date. Comorbidities were identified based on the presence of at least one diagnosis during outpatient visits, emergency visits, or hospitalization prior to the index date. We calculated Charlson comorbidity scale according to the above information. We recorded medications, including BP-lowering agents (details shown below), antilipidemic agents (statins, fibrates, and ezetimibe), antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants (unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin, and direct oral anticoagulants), GLDs (oral and parenteral drugs), and anti-inflammatory agents (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents and cyclo-oxygenase 2 inhibitors). Medication use was deemed positive if the patient received the index medication for at least 28 days within one year prior to the index date. According to prior reports12, this approach reassured the highest number of cases identified and the retention ratio of BP-lowering agents in the local population was fair31. Laboratory data, including glycemic profiles, lipid panels, and serum creatinine levels, were also documented. eGFR was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula.

Exposure variables

We focused on the effects of BP-lowering agents on patient outcomes. The class of BP-lowering agents examined in this study included ACEIs, ARBs, CCBs, diuretics, α-blockers, and β-blockers. The users were identified using the same set of medication use criteria outlined above. The patients were divided into users and non-users of each medication class, followed by a comparison.

Outcome determinations

The primary outcome of this study was the occurrence of worsening frailty, defined according to at least one FRAIL score increase from patients’ baseline status, as adopted in our prior study12. In brief, we operationalized frailty based on the FRAIL scale, a validated tool proposed by the International Association of Nutrition and Aging (IANA)32 to identifying frailty in populations including older adults and patients with various comorbidities, regardless of age, using clusters of international classification of disease (ICD) codes, physical, and procedural documentations. FRAIL scale has been recommended by the International Conference of Frailty and Sarcopenia Research (ICFSR) as an optimal frailty-diagnostic approach3. A prior meta-analysis endorsed the role of FRAIL scale in identifying frailty in patients with DM and its findings correlated with diabetic complications and mortality33. Previous studies further demonstrated that increases in FRAIL item counts were closely associated with greater frailty severities and aggravated health status in patients with DM and/or CKD34,35,36. At baseline, we also recorded patients’ frail assessment results, in the form of the prevalence of each FRAIL item.

Statistical analysis

We used mean values ± standard deviations and medians with interquartile values to describe normally and non-normally distributed continuous variables, respectively. Continuous variable distribution was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical variables were described as numbers and percentages. Comparisons between groups were performed using t tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, and chi-square tests, if appropriate. After follow-up, the patients were divided into those with and without worsening frailty over time. We compared the demographic profiles, baseline FRAIL item prevalence, comorbidity status, concurrent medications, and laboratory data between the two groups of patients, and between specific BP-lowering agent use or not. We constructed Kaplan–Meier event curves to depict the cumulative probability of outcomes according to the number of different BP-lowering agent classes and, later, the specific class of BP-lowering agents. The log-rank test was used to compare the probabilities between groups. We also compared the differences in clinical features between each class of users and non-users using the aforementioned statistical tests. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the risk of worsening frailty associated with the number of BP-lowering agent classes used, with or without adjustment for demographic profiles, baseline FRAIL item prevalence, comorbidity status, concurrent medications, and laboratory data. This was followed by analyses focusing on the influence of each class of BP-lowering agent. We used two strategies for confounder adjustment, first incorporating demographic profiles, comorbidity statuses, and concurrent medications (including other classes of BP-lowering agents) (Model 1), followed by the additional incorporation of laboratory data (Model 2) and comorbidity severity/hypertension severity (Model 3). We also performed competing risk analyses, with mortality as a competing event, in our cohort to elucidate the influences of individual BP-lowering agents.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to confirm the validity of the results. We focused on whether there were dose- and duration-dependent associations between specific BP-lowering agents and the risk of worsening frailty among the study patients. The same set of variables was adjusted for during the sensitivity analyses. In addition, we tightened the definition of BP-lowering agent use to at least 28 days of consecutive use within one year after the index date, and re-evaluated results. In all analyses, a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Responses