The role of Klotho and sirtuins in sleep-related cardiovascular diseases: a review study

Introduction

Humans usually spend a third of their lives sleeping. During infancy and childhood, more time is spent sleeping. Although the amount of time adults spend sleeping is different, it eventually reaches the pattern of 7 to 8 h per day1. In 2015, the National Sleep Foundation recommended 7 to 9 h of sleep for young people and adults and 7 to 8 h for the elderly2.

Lifestyle changes have reduced average sleep duration and sleep patterns among different societies. Based on the data published by the National Sleep Foundation there has been a significant decrease in the average sleep duration of Americans in the last 100 years3. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), there are various forms of sleep disorders, such as insomnia, hypersomnia, narcolepsy, sleep disorders related to the respiratory system diseases, and other physical diseases, disorders related to the circadian rhythm, and disorders related to substance abuse4.

Decreased sleep duration is associated with increased fatigue and excessive sleepiness during the day. Sleep disorders are also related to cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), diabetes, cognitive decline, and metabolic syndrome5,6,7. Short and long sleep duration cause atherosclerosis, high blood pressure, and other CVDs8,9. In addition, poor sleep quality is associated with a wide range of adverse health outcomes and subsequent economic burden1. Chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH) and discontinuous sleep at night, which occur as a result of reversible periods of partial or complete collapse of the upper airways, cause a decrease in oxygen saturation of tissue or arterial blood in different periods10. Hypoxia causes hemodynamic disturbance, changes in gene expression, increased cell adhesion, endothelial and mitochondrial dysfunction, and activation of pro-inflammatory factors such as Nf-κB and activator protein 1. Activation of pro-inflammatory factors increases downstream inflammatory mediators and causes oxidative stress, cytokines dysregulation, systematic inflammation, thrombotic factors activation, increased blood coagulation, sympathetic system dysfunction, reduction of nitric oxide (NO) production, and endothelial dysfunction11,12. Dysfunction of the endothelium and vasoconstriction eventually lead to atherosclerosis and vascular aging5. Therefore, the risk of death due to heart attacks, heart failure, atherosclerosis, and hypertension increases in these patients13,14.

The Klotho protein is a multifunctional and age-dependent protein whose expression decreases with age15,16. Klotho expression decreases in age-related diseases such as metabolic syndrome, cancer, and CVDs17,18,19,20,21. Deficiency in this protein causes heart aging22. It has been shown that sleep disorders are more prevalent and frequent in the elderly23,24 and the possibility of CVDs is significant in people over 60 years old who have longer sleep duration25. Similar to Klotho, insufficient or poor quality of sleep also leads to the acceleration of the aging process26. Therefore, it is possible that CVDs caused by sleep disorders are related to changes in the Klotho protein. Various studies have shown that sirtuins, class III histone deacetylases, interact with Klotho protein at the levels of gene expression, protein, and function27. In addition, reduction of sirtuin content or activity is one of the hallmarks of age-related diseases, including chronic CVDs, renal and metabolic diseases, diabetes, some malignancies, and infections28,29,30. Various studies have shown that the regulation of sirtuins is disrupted in sleep disorders31,32,33. This article reviews the role of Klotho and sirtuins in relation to sleep disorders and sleep disorder-related CVDs. The inclusion criteria were the keywords of different types of sleep disorders and CVDs, Klotho, SIRT1-7, and sirtuins. All human and experimental studies indexed in PubMed, Scopus, Embase، Science Direct, Web of Sciences, and Google Scholar by the end of 2023 were included. There were no restrictions on the time of publication and the type of studies design. To avoid losing any relevant articles, references from articles were also reviewed.

Sleep disorders and cardiovascular diseases

The recent guidelines for cardiovascular prevention released by the American College of Cardiology/the American Heart Association (2019) state that counseling on sleep and sleep hygiene (along with advice on physical activity) should be provided to prevent CVDs32.

The relationship between sleep disorders and CVDs has been reported in several review studies12,13,14,33,34,35. The disturbance in quantity and quality of sleep increases the risk of CVDs independently of other risk factors36. A cohort study conducted recently in Shanghai, China, with a follow-up of 5.1 years on 33,883 people aged 20 to 74 years, reported that the prevalence of CVDs in people over 50 years of age is related to increased sleep duration26. A meta-analysis study has also shown that increased sleep duration is related to the prevalence of CVDs9. In another study, it was shown that insufficient sleep, delayed sleep onset, sleep problems, and daytime sleepiness are positively related to various types of CVDs37

High blood pressure is one of the known risk factors for CVDs including coronary heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, and vascular dementia and related disabilities36. Various studies have indicated a link between sleep duration and hypertension risk. Hypertension is more prevalent among people who suffer from sleep disorders38,39. The risk of hypertension in people who have a short sleep period is estimated at 21%40. The reason for increased blood pressure as a result of shortened sleep is the reduction of slow-wave sleep, the restorative stage of sleep. It has been shown that sleep apnea is also associated with hypertension. About 50% of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients have hypertension, 30% of hypertensive patients also have OSA and about 65% to 80% of patients with resistant hypertension suffer from OSA41,42.

OSA is a common respiratory disorder that affects almost one billion people in the world and in some countries, it has a 50% prevalence43. OSA is recognized as an independent risk factor for many CVDs, including coronary artery disease (CAD), stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (HF), and hypertension44,45. In some people, blood pressure doesn’t have a nocturnal dipper pattern. This phenomenon may appear in people who have normal or high daily blood pressure. Compared to dippers, the risk of CVDs is higher than in non-dippers46,47. Therefore, the risk of CVDs may be increased in people whose sleep disorder prevents their blood pressure decreases at night48. It has been shown that changes in the severity of OSA are one of the important risk factors for uncontrolled hypertension49.

Despite differences in the studied population, many studies have shown that those with shorter sleep duration (typically less than 5 or 6 h per night) are more likely to develop coronary heart disease and die from it compared to those with normal sleep duration (6–8 h per night on average). Studies have shown an average 48% increased risk9,50.

In a rat model, it was shown that 72 h of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep deprivation leads to a significant increase in systolic and mean arterial pressure and a significant increase in the QTc interval51,52. Other studies have also reported prolongation of the QT interval following sleep disturbances53,54. OSA is known to cause several types of arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation (AF). OSA can independently induce structural changes and remodeling in the right atrium, which predisposes patients to AF55.

According to the findings of the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) cohort study, there is a direct relationship between the duration of sleep (5 h or less) and the risk of coronary artery calcification and heart attack risk factors; this relationship is stronger in women56. In rats, chronic insomnia causes a decrease in the ejection fraction and fraction shortening of the heart, and an increase in fibrosis, heart hypertrophy, and atherosclerosis57. A persistent increase in oxidative stress in patients with OSA may explain the increased risk of CVDs. Insomnia58 and excessive sleep duration are involved in the risk of inflammatory and infectious diseases, which in turn increase all-cause mortality59.

Klotho, sleep disorders, and cardiovascular diseases

Klotho, a β-glycosidase-like protein, is an anti-aging protein whose level naturally decreases with normal human aging60. Klotho has a short transmembrane domain and two long extracellular segments with similar sequences61. Three types of membrane Klotho have been identified: α-Klotho, β-Klotho, and γ-Klotho. Although they have similarities, they are functionally distinct62. The extracellular parts of α-Klotho are segregated by A disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10 (ADAM10) and ADAM17 and enter the blood circulation as soluble Klotho (S-Klotho)63. There is a strong correlation between α-Klotho gene expression and the secreted form of plasma protein64. S-Klotho affects tissues and cells that do not express the Klotho gene themselves62. α-Klotho expression has been found mainly in distal convoluted tubule cells in mice, rats, and humans15 and to a lesser extent in proximal tubule epithelial cells65 and the parathyroid gland66. α-Klotho expression has been detected in other tissues of rodents and humans, including the pituitary gland, pancreas, ovaries, testes, placenta, and brain choroid plexus15. Klotho has also been reported in the rat aorta67 and in human arteries68. S-Klotho is produced mainly in the kidneys and to a lesser extent in the brain, skeletal muscles, bladder, aorta, gonads, and thyroid15. It has been found that S-Klotho has endocrine, autocrine, and paracrine activity56. S-Klotho exerts its effects by binding to its receptor or as an enzyme acting on the glycoprotein receptors on the cell surface or different enzymes in different tissues and organs65,69,70.

Membrane Klotho together with fibroblast growth factors receptors (FGFRs) forms a common receptor (unit) for many fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and plays an essential role in the activation of their receptors71,72,73. α-Klotho and S-Klotho deficiency is associated with aging-related disorders such as CVDs74, type 2 diabetes75, and chronic kidney disease72,76,77. A strong relationship between S-Klotho and all-cause mortality has also been reported78. The level of Klotho in the heart and serum, and the serum level of ADAM-17 enzyme decreased in rats with myocardial infarction79. Exercise along with hind limb blood flow restriction increases Klotho expression in the heart tissue of old rats and improves heart function80,81. It has been reported that in pre-hypertensive people, the S-Klotho level decreases, but in people with hypertension it returns to normal levels82.

The relationship between sleep and Klotho levels has been investigated in various studies. The results of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that S-Klotho levels decrease with longer sleep duration. There is a non-linear relationship between sleep duration and serum Klotho levels so when sleep duration exceeds 7.5 h, a decreasing trend in S-Klotho level is observed. In this study, it was also shown that the highest levels of S-Klotho were observed in people whose sleep duration was 5.5 h. In these people, S-Klotho levels had a negative correlation with smoking, high blood pressure, CVDs, and heart attacks83. In an animal model, it was shown that tobacco consumption reduces the levels of SIRT1, SIRT3, and Klotho in the heart and changes the structure and function of the heart81.

There are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the Klotho gene and the level of Klotho expression depends on the different alleles of the Klotho gene. People whose Klotho levels were lower due to SNPs had symptoms of hypoxia, OSA, and hypertension. In these people, the telomere length was shorter than normal. Researchers concluded that the reduction of Klotho can be a reason for sleep disorders in these people (Table 1)84

A study on sedentary middle-aged people reported an inverse relationship between S-Klotho plasma level with components of global Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score (higher scores indicate poorer sleep quality) after adjusted with factors including age, total fat mass percentage, fat mass index, and lean mass index85.

Since the reduction of S-klotho, α-Klotho, and β-Klotho is one of the reasons for the advancement of atherosclerosis21,86, their reduction in blood can be the explanation for the advancement of atherogenic lesions, the proliferation of smooth muscle cells, and the formation of atherosclerotic plaques caused by hypoxia in people with respiratory apnea. Intermittent hypoxia as a result of intermittent sleep apnea has been shown to promote atherogenic lesions87,88.

There are conflicting findings about Klotho changes in sleep disorders. In one study it has been shown that S-Klotho levels increase with sleep disorders89. Also, α-Klotho and FGF-23 levels in Korean firefighters who were shift workers were higher than those of traditional day workers, which could be due to compensatory mechanisms to deal with inflammatory factors released as a result of reduced sleep quality90. It is possible that the type of sleep disorder, the time of Klotho measurement, and the duration of sleep deprivation have important effects on the Klotho levels in the serum.

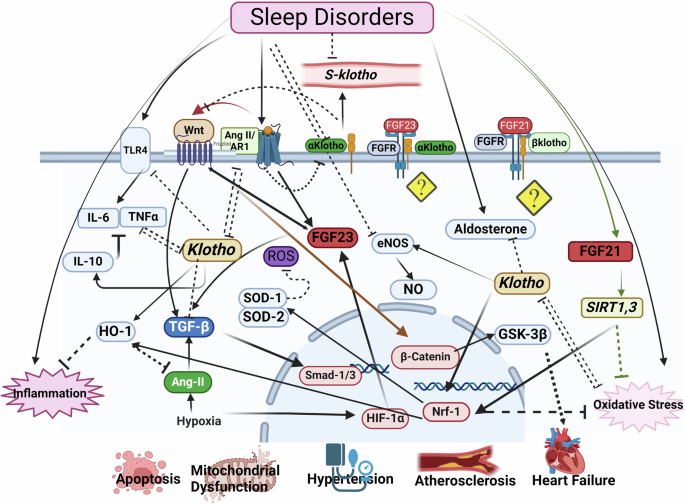

Sleep disturbance is associated with the increased risk of inflammatory diseases and increased all-cause mortality, possibly due to the activation of inflammatory mechanisms. A meta-analysis showed that sleep disturbance and long sleep duration, but not short sleep duration, are associated with increased markers of systemic inflammation91. However, experimental studies have shown that even a small decrease in sleep duration activates inflammatory transcriptional signals91, which leads to an abnormal toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) mediated increase in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) by monocytes92,93. A large sample size study with a five-year follow-up showed that insomnia and short sleep duration were associated with increased systemic inflammation as indicated by increased plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) and IL-694. Inflammatory factors including TNF-α decrease Klotho expression94,95. On the other hand, Klotho reduces the expression of pro-inflammatory factors and increases the expression of anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-1096. IL-10 inhibits the expression of many pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α97. In addition, Klotho down-regulates TLR4 through a deglycosylation process98. Inflammation is the cause of many CVDs, including hypertension and atherosclerosis. The formation and progression of atherosclerosis and the thinning and separation of the atherosclerotic plaque cup and, as a result, the process of thrombus formation are caused by inflammatory processes that are reversely correlated with klotho levels (Fig. 1)99.

The bioRender tool Utilized for the creating the figure. Ang-II: Angiotensin-II, eNOS: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase, FGF-23: Fibroblast growth factors-23, FGFR-21: fibroblast growth factors -21, GSK-3β: Glycogen synthase kinase-3, HIF-1α: Hypoxia-Inducible Factor, HO-1: Heme oxygenase-1, NO: Nitric oxide, Nrf-2: Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, SOD1: Superoxide dismutase 1, SOD2: Superoxide dismutase 2, TLR-4: Toll-like receptor 4, TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress are closely related to hypoxia in OSA patients100. The amount of ROS in the heart of rats that have chronic sleep deprivation (CSD) increases, and this increase is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. The levels of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) and superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) decrease and the level of malondialdehyde (MDA) increases in these rats. The levels of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf-2) proteins associated with mitochondrial quality also decrease in the heart tissue of CSD rats101. HO-1 is an Nrf-2-regulated gene that plays an important role in the prevention of vascular inflammation102. Klotho deficiency causes cardiac aging through disruption of the Nrf-2 pathway22. Many studies have shown a two-way interaction between oxidative stress and Klotho103,104 (Fig. 1).

One of the other signaling pathways through which Klotho may improve the function of the cardiovascular system is nitric oxide (NO). NO is involved in several biological functions, including the regulation of vascular tone and inflammation105. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and NO play a key role in the regulation of vascular tone, and disruption in their production leads to atherosclerosis for any reason, including hypertension and diabetes106. Circulating NO levels decrease in subjects with OSA, suggesting that NO is one of the mediators involved in the regulation of vascular homeostasis in OSA107. On the other hand, s-Klotho is suggested as a cardiovascular system “protector” by means of endothelium-derived NO production108.

Dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is one of the most important causes of CVDs, including hypertension and heart failure109,110. Deleterious changes in this system have been reported in old animals; increasing the level of serum angiotensin 2 (Ang II) and angiotensin type 1 receptor (AR1) in the heart and aorta of old rats109. An increase in the serum levels of Ang II along with an increase in the expression of its type 1 receptor cause cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling, and the growth of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) by activating the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway111,112 and accelerate the aging process of the heart through the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway and Klotho inhibition113. There is a mutual relationship between Klotho and RAS, meaning that Klotho reduces the expression of RAS components such as the production of renal angiotensinogen, renin, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), AR1, and response to Ang II. On the other hand, Ang II reduces the expression of Klotho114,115, potentially creating a vicious cycle that increases the severity of target organ damage.

Klotho modulates blood pressure by interfering with the Ang II signaling pathways, and Klotho deficiency is thought to underlie salt-sensitive hypertension. Klotho gene polymorphism is related to salt-sensitive hypertension in humans116. Klotho administration inhibited salt-induced hypertension in old mice and in young Klotho-knockout heterozygous mice117. On the other hand, it has been shown that the amount of Ang II in hypertensive people who simultaneously suffer from respiratory apnea is higher than in normal; and this increase has a direct relationship with the severity of OSA118. The reduction of Klotho can cause cardiovascular complications with the increase in aldosterone levels. Blocking Klotho leads to increased aldosterone production and subsequent hypertension in rats119. On the other hand, hyperaldosteronism has been observed in OSA120. Klotho inhibits some of the effects of Ang II, including cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and cardiac dysfunction, through suppression of the transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) signaling pathway. Klotho also inhibits cardiomyocyte fibrosis and hypertrophy induced by TGF-β1 and Ang II in the culture medium121.

Three members of the FGF family, FGF-23, FGF-21, and FGF-19, act as endocrine FGF and need Klotho to bind to their receptors. FGF-23 requires α-Klotho to bind to its target receptors FGFR1c, FGFR3c, and FGFR469,71.

A study conducted on the data of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) cohort study, showed that the level of cFGF-23 was higher in people with severe sleep disorder compared to the control group, but the level of iFGF-23 did not change; which indicates that sleep disorder causes disturbance in FGF-23 transcription122. When UMR-106 cells grow in an oxygen-free environment, the FGF-23 transcription increases122. This increase is in line with the increase in hypoxia-inducible Factor (HIF-1α) protein expression, suggesting that there is a significant increase in FGF-23 mRNA expression in response to cellular hypoxia123. Periodic hypoxia can also directly stimulate HIF-1α expression and FGF-23 transcription in the bone124,125. In narcolepsy patients, the level of FGF-23 and Klotho in the cerebrospinal fluid increases and decreases, respectively126 (Fig. 1).

Experimental data show the negative effects of FGF-23 on cardiac myocytes through the activation of the FGFR-4127. The relationship between the increase in FGF-23 levels in the serum of patients suffering from heart failure with reduced or preserved EF and patients with chronic congestive failure has been reported, and this increase coincides with a significant decrease in plasma Klotho128,129. FGF-23 leads to pathological cardiac remodeling by activating pathways such as TGFβ. Ang II also leads to fibrosis by increasing the expression of FGF-23 in cardiac cells130.

Studies have shown a change in the level of S-Klotho, not the membrane forms of Klotho, in sleep disorders. Although the level of S-Klotho is a mirror of the level of α-Klotho expression, the change in the level of S-Klotho can be due to the change in the enzymes activity that separate the extracellular part of membrane Klotho, releasing S-Klotho as a result79. On the other hand, it has been shown that S-Klotho reduces the effects of FGF-23 by forming the heterodimer with FGFR1C-4131. So, the reduction of S-Klotho and the increase of FGF-23 in sleep disorders may lead to cardiovascular damage. Increased FGF-23/Klotho ratio that occurs in the early stages of CKD is associated with CVDS, especially left ventricular hypertrophy and vascular calcification131,132. More studies are needed to determine the level and function of membrane Klotho, and the enzymes (ADAM10, and ADAM17) that separate the extracellular part of the α-Klotho in sleep disorders and periodic hypoxias caused by respiratory apnea.

An acute decrease in sleep duration leads to an increase in circulating levels of FGF-21 in healthy young men133. FGF-21 and FGF-19 require β-Klotho to function. Various studies have shown the protective role of FGF-21 against various damages, including diabetic cardiomyopathy and heart failure134. FGF-21 also reduces oxidative stress and protects the heart against oxidant agents by activating the SIRT1 signaling pathway135,136. Serum levels of FGF-21 are greatly increased in subjects with OSA, and there is an independent relationship between the levels of circulating FGF-21 and the risk of OSA. People whose FGF-21 levels were in the highest quarter were almost three times more likely to develop OSA than people who were in the lowest quarter137. Although FGF-21 has increased, its effect probably depends on the expression level of its specific receptors as well as β-Klotho. However, the change in the expression of β-Klotho in sleep disorders, its role, and the inhibitory or stimulating effect of S-Klotho on the β-Klotho/FGF-21 signaling pathway have not been studied so far. It is possible that this increase is the result of decreased sensitivity to FGF-21. In diet–obesity rats, the increase in the FGF-21 level is possibly due to the decreased sensitivity to FGF-21138. Higher levels of FGF-21 were detected in patients with coronary heart diseases and were associated with unfavorable lipid profiles such as increased triglycerides and decreased apolipoprotein A1 levels139. Incubation of cardiac endothelial cells with oxidized low-density lipoprotein increases FGF-21 expression and induces apoptosis of endothelial cells140. After adjustment with multiple variables, increased serum FGF-21 levels were associated with hypertension. Elevated FGF-21 levels were also associated with higher systolic blood pressure in type 2 diabetic patients141.

FGF-21 may have a protective role against stress in sleep disorders. Sleep disorders such as increased NREM sleep duration and decreased wakefulness after exposure to social stress are greater in FGF-21 deficient rats than in the control group142. Deletion of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα), an upstream factor of FGF-21, alters sleep quality as well as plasma levels of ketone bodies in rats143.

FGF-19 is another member of the circulating FGF family. FGF-19, called FGF-15 in rats, is secreted from the intestine. During feeding, it acts on the liver to suppress bile acid synthesis and induce insulin-like metabolic responses144. Based on existing knowledge, there is no study showing its changes in sleep disorders.

The Wnt signaling pathway, which is related to circadian rhythm, is regulated by Klotho and FGF-23145. Klotho inhibits oxidative stress through the Wnt signaling pathway103. The Wnt signaling pathway is involved in many cardiovascular pathological processes such as endothelial dysfunction, vascular calcification, atherosclerosis, cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy, myocardial infarction, and arrhythmia145. FGF-23 mediates left ventricular hypertrophy through the Wnt signaling pathway. Inhibition of Wnt signaling has been shown to improve cardiac function146. Although there is little evidence for direct interaction of FGF-23 or Klotho with Wnt, the extracellular domain of Klotho binds to multiple Wnt ligands and inhibits their ability to activate Wnt signaling.

Klotho also inhibits the hypertrophic effects of Ang II by suppressing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and decreasing AR1 expression147. In addition, TGF-β, a key profibrotic cytokine in the development of cardiac fibrosis, acts through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by increasing the amount of Wnt protein and deactivating the GSK3β pathway. Activated Wnt/β-catenin, in turn, stabilizes the TGF-β/Smad response148. These studies show a close relationship between the activation of Klotho, TGF-β, and Wnt signaling in the development of fibrosis. The atherosclerosis process is also associated with the activation of the Wnt signaling pathway. There is a positive correlation between the severity of the atherosclerotic lesion and the serum level of Wnt5a149. There is a reciprocal relationship between Klotho, FGF-23, and Wnt signaling. Thus, disruption of the Wnt signaling pathway affects the levels of FGF-23 and Klotho and vice versa. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) which consists of two isotypes, GSK-3α and GSK3-β, is a serine/threonine kinase involved in the regulation of glycogen synthase. Abnormal expression of GSK-3β is associated with heart diseases (Fig. 1)150. GSK-3β is phosphorylated and inhibited by the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway151.

Sirtuins, sleep disorders, and cardiovascular diseases

The sirtuin family, known as silencing information regulator 2 (Sir2) proteins, belongs to class III nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent histone deacetylases. Seven sirtuins (SIRT1 to SIRT7) are known in humans and other animals. Each isoform is localized in different parts of the cell. SIRT1, SIRT6, and SIRT7 are mainly located in the nucleus, SIRT2 is exclusively in the cytoplasm, and SIRT3, SIRT4, and SIRT5 are mitochondrial sirtuins152. SIRTs are known as major cellular regulators and depending on different biological processes, they have different substrates, including histones and non-histone proteins, transcription factors, and enzymes152. SIRTs play a role in regulating the main functions of the cell, including glucose and lipid metabolism, mitochondrial biogenesis, DNA repair, oxidative stress, apoptosis, inflammation, and ultimately delaying cellular aging and increasing lifespan in organisms153,154.

The potential role of sirtuins in the pathology of various CVDs such as heart failure, cardiac hypertrophy, and endothelial dysfunction has been clarified155,156,157,158. SIRT1 deficiency increases inflammation and oxidative stress, impairs NO production and autophagy, and causes vascular aging and atherosclerosis152. Under stress conditions, SIRT1 migrates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Its migration is essential for the activation of SOD and its protective effects, which in turn enhances cellular resistance to oxidative stress. The inhibition of SIRT1 activity increases the probability of cardiac cell death159. SIRT1 expression in the heart increases in hypertension and ischemic conditions and during exercise while it decreases in reperfusion injury160,161,162. SIRT1, SIRT3, and SIRT6 have a protective effect on cardiac fibrosis by regulating the activity of the Smad family transcription factor and TGF-β gene expression163. However, the effect of SIRT1 on cardiac hypertrophy is contradictory, it appears that its effect depends to a large extent on its expression and activity154.

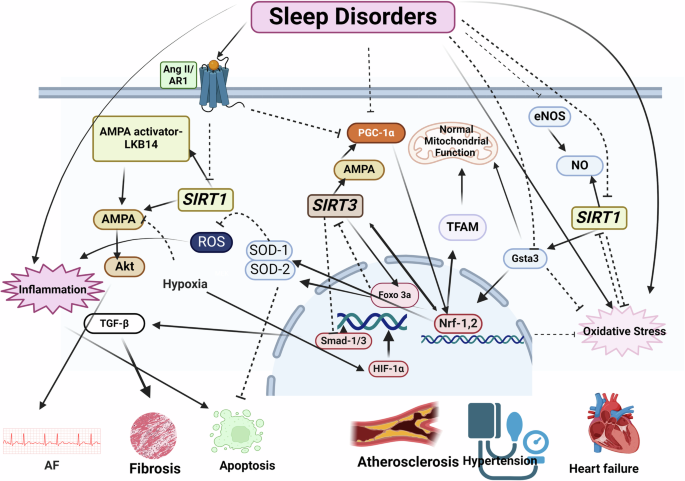

It has been shown that in people with sleep apnea, the activity and the level of SIRT1 and the amount of NO metabolites are lower than normal, and the decrease in SIRT1 is directly related to the decrease in blood oxygen levels164. SIRTs, like Klotho, can prevent the harmful effects of sleep on the cardiovascular system by regulating oxidative stress154,159,165. Oxidative stress in sleep disorders can be a factor in the reduction of SIRT1 production. In a study conducted with RNA-seq analysis, it was shown that the expression of various genes changes in the heart of experimentally sleep-deprived rats. These animals’ hearts were hypertrophied and fibrosed and their function was reduced due to sleep deprivation. Among these genes, the genes involved in nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism and the metabolic pathways whose disruption causes damage to mitochondrial function were significantly changed. The mRNA and protein expression of SIRT1 and glutathione s-transferase A3 (Gsta3) were greatly reduced. ROS production was increased and the mitochondrial function was changed in the hearts of these rats. Antioxidant administration increases the expression of SIRT1, Gsta3, and Nrf-2101. Gsta3 expression is dependent on SIRT1 and increased Gsta3 expression reduces oxidative stress166. Nrf-2 is a redox-sensitive transcription factor that activates the transcription of antioxidant, cytoprotective, and anti-inflammatory genes167. SIRT1 mediates antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cell protection effects by regulating Nrf-2 expression168. Phosphorylation of AMPK and AKT, which are essential pathways for regulating cellular metabolism, is decreased in long-term sleep-deprived hearts compared to control hearts. Hypoxia inactivates the SIRT1-AMPK pathway, which leads to the regulation of metabolic imbalances under hypoxic conditions and helps cells utilize glucose and survive in adverse conditions169. The intermittent hypoxia that occurs in OSA can eventually cause CVDs by disrupting the use of glucose and fatty acids. Decreased activity of SIRT1 and AMPK has been reported in the atrium of dogs with chronic OSA. SIRT1 activates AMPK by deacetylating AMPK and activating the AMPK activator LKB14. Due to the decreased activity of the SIRT1- AMPK signaling pathway in these animals, AF is seen along with metabolic, structural, and neurological reconstruction (Fig. 2)170.

The bioRender tool Utilized for creating the figure. Akt: Protein kinase B, AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase, Ang-II: Angiotensin-II, eNOS: Endothelial nitric oxide synthase, FOXO3a: Forkhead box transcription factors, Gsta3: Glutathione s-transferase A3 HIF-1α: Hypoxia-Inducible Factor, IL-6: Interleukin 6, NO: Nitric oxide, Nrf-2: Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, PCG-1α: Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ-1α, SIRT-1: Sirtuin-1, SIRT3: Sirtuin-3, SOD1: Superoxide dismutase 1, SOD2: Superoxide dismutase 2, TAFM: Mitochondrial transcription factor A, TGF-β: Transforming growth factor-β.

The results of a human study showed that in patients with OSA, the telomere length of white blood cells was shorter than normal and the level of SIRT1 protein decreased. Three months of treatment with a mandibular advancement device (MAD) returned SIRT1 levels to normal levels171. SIRT1 prevents telomere shortening, vascular aging, and CVDs by increasing the production of endothelial NO172. Telomere shortening is an indicator of aging, thus periods of hypoxia lead to premature aging of cells by reducing telomere length.

In another study, it was shown that chronic hypoxia in rats decreases SIRT1 in the heart. In these animals, the AR1 inhibitor increases SIRT1 levels. Considering that the level of Ang II increases in sleep disorders, one of the ways to reduce the expression of SIRT1 can be mediated by Ang II173.

SIRT3, which is one of the important sirtuins in CVDs, is presented in mitochondria174,175. In the aorta of rats with CIH, a decrease in SIRT3 expression has been observed176, which can be one of the causes of hypertension in people with sleep disorders. Decreased SIRT3 in hypertension causes endothelial dysfunction, vascular hypertrophy, vascular inflammation, and end-organ damage. Excessive expression of SIRT3 prevents oxidative stress154 and reduces blood pressure in hypertensive rats induced by Ang II and deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt174. SIRT3 level in the arteries of people with primary hypertension is lower compared to people with normal blood pressure; and similar to rats whose SIRT3 has been knocked down177, it is associated with manifestations in vascular metabolic pathways and inflammation. The decrease in SIRT3 level in response to the increase of HIF-1α causes metabolic and phenotypic changes in blood vessels174.

It has been shown that 8 weeks of CIH causes heart tissue disorder, but this disorder is different in the hearts of young rats compared to old ones. In young rats, heart remodeling is accompanied with an increase in the amount of collagen in the interstitial and perivascular areas. However, the dysfunction of mitochondria is more obvious in old rats. In the hearts of young rats under CIH conditions, the expression of SOD-2, SIRT1, SIRT3, mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-γ-1α (PCG-1α), and Nrf-1 and -2 increases. Activation of these signaling pathways maintains the integrity and normal function of mitochondria. However, the fibrosis caused by hypoxia causes premature aging of the heart in these rats31. Increased SIRT3 expression activates the forkhead box transcription factors (FOXO3a)-SOD2 pathway and neutralizes ROS produced by mitochondria during the process of intermittent periods of hypoxia in the heart through deacetylation and activation of FOXO3a177,178. SIRT3 maintains mitochondrial structure and function by activating the AMPK/PGC-1α signaling pathway and maintaining mitochondrial membrane potential. Nrf-1 and TFAM expression changes along with the change in SIRT3 expression31. As an upstream molecule of TFAM, Nrf-1 activation can increase TFAM expression and mediate functions such as transcription, maintenance, replication, and repair of mitochondrial DNA179. Another study also showed that the SIRT3-AMPK-PGC-1-α pathway is involved in the regulation of Nrf-1 and its downstream TFAM180. It has also been seen in humans that there are more obvious changes in the weight of the left ventricle in people under 65 years old who have OSA than in people over 65 years old181 (Fig. 2).

PGC-1α dysregulation is also involved in sleep disorders. There is an association between primary insomnia and PGC-1α polymorphism. The GG PGC-1α allele may be associated with insomnia in individuals with and without psychiatric diagnoses182. PGC-1α is a peroxisome proliferator PPARα-activated receptor-γ activator, which is the main regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. The level of mitochondria regulates mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and glucose metabolism, reduces oxidative stress damage by eliminating excess ROS and inducing antioxidant enzyme expression, and ultimately maintains mitochondrial function. PGC-1α stimulates several nuclear transcription factors, including Nrf-1, Nrf-2, and estrogen receptor α (ERR-α). PGC-1α regulates TFAM expression by interacting with Nrf-1 and Nrf-2. TFAM and mitochondrial RNA polymerase then work together to bind to specific promoters and increase the transcription of mtDNA genes183. Prolonged exposure to hypoxia significantly decreases the expression of both PPARα and PGC-1α. Therefore, the expression of its target genes is affected. Loss of PGC-1α in knockout rats leads to significant defects in cardiac mitochondria and energy production mechanisms and makes the animals prone to heart failure183. In old rats, exercise increases the expression of PGC-1α, which improves the function of the heart and skeletal muscles by improving the function of mitochondria80,184 (Fig. 2).

PGC-1α expression in different parts of the heart can be affected by oxygen levels in various ways. The responses of left and right ventricles to hypoxia are different. Hypoxia significantly decreases PGC-1α protein and mRNA levels in both left and right ventricles in rats185. However, another study showed that in rats exposed to hypoxia for 4 weeks, the expression of PGC-1α in the left ventricle did not change, but it decreased significantly in the right ventricle186.

The level of Ang II can mediate the effects of sleep disorder on the PGC-1α signaling pathway. Ang II reduces the expression and function of PGC-1α in vascular smooth muscle cells through transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms and increases oxidative stress, migration, proliferation, and cellular aging187.

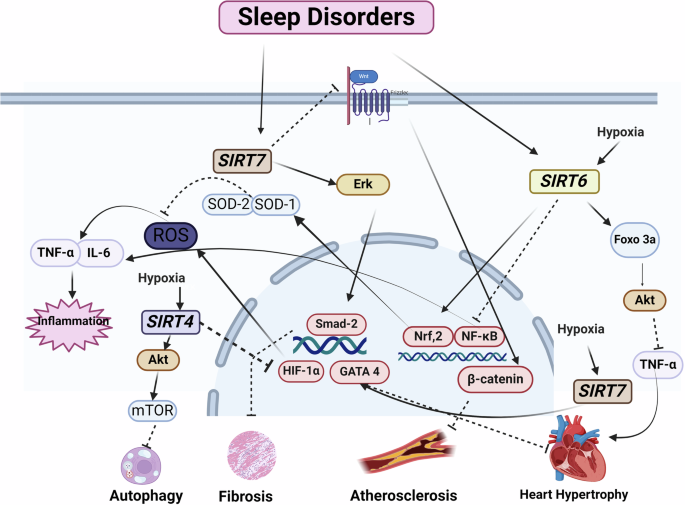

CIH increases the expression of SIRT4, SIRT6, and SIRT7 in the heart of young rats176. The increased expression may indicate compensatory responses against hypoxia. It is possible that SIRT4 reduces the accumulation of ROS by inhibiting HIF-1α, which is an important mechanism underlying the activity of SIRT4 in regulating oxidative stress188. Laboratory studies have shown that hypoxia can increase HIF-1α levels, which activates hypoxia-responsive genes and disrupts the circadian rhythm. HIF-1α is chronically increased in OSA patients. A human study showed that OSA patients had higher levels of HIF-1α than the control group189. Evidence has shown that increasing the expression of HIF-1α by stimulating the production of ROS in response to the CIH caused by repeated apnea is one of the mechanisms of hypertension189. HIF-1α protein level increased in the heart and abdominal aorta of rats after CIH190 (Fig. 3).

The bioRender tool Utilized for creating the figure. Akt: Protein kinase B, FOXO3a: Forkhead box transcription factors, HIF-1α: Hypoxia-Inducible Factor, ROS: Reactive oxygen species, TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor alpha.

SIRT4 overexpression inhibits both ROS production and autophagy by activating the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Therefore, another protective mechanism can be through this path191. There are conflicting findings with regards to the importance and role of SIRT4 in CVDs. SIRT4 has adverse effects on cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. For example, an in vivo study has shown that overexpression of SIRT4 exacerbates Ang II-induced cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting SOD activity. SIRT4 knockout reduces cardiac fibrosis in response to Ang II192.

Evidence suggests that SIRT7 has a protective effect on cardiac hypertrophy, but its effect on cardiac fibrosis is inconsistent. SIRT7 ameliorates stress-induced cardiac hypertrophy by deacetylating GATA4193. Increased expression and phosphorylation of SIRT7 are involved in the development of cardiac fibrosis through the activation of Smad2 and ERK signaling pathways194. Lastly, it has been reported that SIRT7 prevents the progression of atherosclerosis by inhibiting the proliferation and migration of VSMC through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway195.

The expression of SIRT6 increases in the heart of young rats exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia176. SIRT6 reduces inflammatory responses by suppressing the expression of pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF-α through the NF-κB pathway. For example, SIRT1 and SIRT6 both inhibit vascular inflammation induced by TNF-α activation through the regulation of ROS and protein kinase B (Akt) signaling pathways196. SIRT6, like SIRT1 and SIRT2, can activate Nrf-2 and regulate antioxidant gene expression through it, combating oxidative stress damage. SIRT6 reduces hypertrophy in rats by promoting the expression of the FoxO3 transcription factor and through the Akt pathway. SIRT6 also prevents cardiac hypertrophy by reducing NF-κB activity154.

Despite the importance of SIRT4, SIRT6, and SIRT7 in the physiopathology of CVDs, studies on their role in sleep disorders are limited and need further investigation.

Several studies have shown the interaction between Klotho and sirtuins at the levels of gene expression, translation, and activity regulation27. The first study in this field showed that the activity and level of SIRT1 were decreased in Klotho knockout rats; in these animals, vascular remodeling and blood pressure in response to Ang II are increased. There is a direct relationship between the serum levels of Klotho and SIRT1 in people with prehypertension and hypertension82,197. In addition, in rats suffering from heart attack, the levels of Klotho and SIRT1 decreased along with each other, and exercise increased both of them79. Therefore, it is possible that the changes in sleep disorders in each simultaneously aggravate the other one’s harmful effects (Fig. 3).

As shown in Table 1, studies relating changes in the expression and level of klotho protein are limited in sleep disorders. Most studies have proved an inverse relationship between Klotho and sirtuins with sleep disorders. However, the association of different types of sleep disorders and severity of sleep disorder with Klotho and sirtuins has not been studied. The relationship between changes of Klotho and sirtuin levels with sleep disorders in gender was not recognized. Although the aim of this study was the association between changes in klotho and sirtuins with sleep disorders-related CVDs and possible signaling pathways, studies that directly investigated this link are limited.

Conclusion

Sleep disorders, especially intermittent hypoxia as a result of respiratory apnea, lead to changes in the serum and tissue levels of Klotho and sirtuins, including SIRT1 and SIRT3. The relationship between sleep disorders and changes in Klotho and sirtuins levels is bidirectional. The response of the cardiovascular system to hypoxia is influenced by age. OSA is more common in the elderly, and Klotho, a longevity-related protein, is decreased in the elderly and people with sleep disorders; therefore, sleep disorders are likely to be associated with the aging process and age-related diseases such as CVDs through disruption of the Klotho signaling pathway. The reduction of sirtuin activity, which is one of the obvious symptoms of age-related diseases, is also related to CVDs caused by sleep disorders. Considering the interaction between Klotho and sirtuins and their common signaling pathways, ultimately, the reduction of Klotho and sirtuins advance the process of CVDs by disrupting common pathways such as NO production, oxidative stress regulation, control of mitochondrial function, and inflammation. The increase of Ang II, which decreases the expression of Klotho, SIRT1, and SIRT3, is one of the important mediators in sleep disorders and one of the main mediators of CVDs. PGC-1 dysregulation in sleep disorders through disturbance of mitochondria quality control mediated the CVDs. Most of the findings have shown the protective importance of S-Klotho, but the role of membrane Klotho (α, β, and γ-Klotho), which are an essential part in transmitting the message of FGFs, is unknown. However, changes in the expression of FGF-21 and FGF-23, which are mediators of CVDs, have been reported in sleep disorders.

Responses