Innovative perspectives on the discovery of small molecule antibiotics

Introduction

Antibacterial-resistant infections represent a pressing global health concern due to their increasing prevalence and the limited effectiveness of treatment options. Globally, antibacterial resistance is associated with 4.95 million deaths per year1, a figure predicted to escalate to 10 million by 20502. The challenge is especially formidable for Gram-negative bacterial infections as Gram-negative cell envelopes are characterized by low permeability and high drug efflux3, which decreases drug accumulation and renders many antibiotics ineffective4. Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) outlined a priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria based on a multi-criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) that included mortality, incidence, health burden, resistance trend, transmissibility, preventability, treatability, and success prospects of current antibacterial pipelines5. Using the MCDA analysis, the WHO classified the pathogens into critical, high, and medium categories. Not surprisingly, the top three bacteria prioritized as critically in need of new antibiotic therapies belong to the Gram-negative group.

The urgent demand for new antibiotics is not matched by a constant supply of new antibiotics, as antibiotic discovery is incredibly challenging6,7,8. After the golden era of antibiotic discovery in the 1950s and the synthesis of more potent derivatives in the 1970s, antibiotic development programs became increasingly risky for pharmaceutical companies because of their low-profit prospects9. One reason is that antibiotics have a limited lifespan due to the natural evolution of resistance, shortening the time to generate investment returns9. Consequently, previous decades have seen a continuous decline in new antibiotic approvals, with only 13 new drugs approved between 2017 and 202310. In an effort to guide the discovery of antibiotics that can provide effective treatments for resistant infections, the WHO has set four critical innovation criteria for the development of new antibiotics: novelty regarding chemical class, molecular target, mode of action (MoA), and lack of cross-resistance with current antibiotics10. So far, only two of the 13 newly approved antibiotics have met at least one of the WHO innovation standards.

To fulfill the WHO criteria, one could consider cutting-edge alternatives to classic antibiotics, such as biologics, including bacteriophages and monoclonal antibodies11. However, these innovative approaches will require different regulatory and marketing strategies for approval. Instead, innovation applied to small-molecule antibiotics, chemically defined active compounds of natural or synthetic origin, and molecular weights of approximately 400 to 1200 Daltons7,12, can benefit from accumulated knowledge and lessons learned from previously exploited approaches, shortening the pathway to success. To explore this idea in more detail, here we focus on innovation applied to the challenges of discovering and developing “traditional” small-molecule antibiotics. We will first summarize approaches used to discover small-molecule antibiotics in the last two decades, highlighting their challenges. Then, using the innovation criteria established by the WHO, we will highlight approaches that successfully find drugs that meet the innovation criteria. Finally, we will discuss whether this combined innovation is receiving enough attention and how it can address the antibiotic discovery shortage.

An overview of how antibacterial compounds are discovered

Compounds with antibiotic potential obtained from natural sources or chemical synthesis can be revealed by screening against whole bacterial cells or bacterial targets. To test large numbers of compounds, high-throughput screens (HTS) are usually employed13. For natural products, Mother Nature has provided soil fungi and bacteria with chemical weapons that can be extracted and screened for bacterial growth inhibition (whole-cell screening). Historically, based on the “Waksman Platform”14,15, this strategy fueled the golden age of antibiotic discovery and led to the identification of most antibiotics still in use today16. On the other hand, whole-cell screening of synthetic small-molecule libraries is another widely used method that involves testing defined chemical compounds directly on live bacterial cells to identify those with whole-cell antimicrobial activity17.

An alternative to whole-cell screening approaches is target-based screening, which emphasizes the importance of target identification for antibiotic discovery. As such, many antibiotic discovery programs shifted to target-based approaches, which identify compounds that inhibit purified bacterial targets (i.e., essential proteins or enzymes) in vitro17. However, these in vitro active compounds often lack whole-cell activity, especially in Gram-negative bacteria, which have an additional outer membrane that can prevent compound entry18. The “Lipinski Rule of Five” (Ro5), used to filter compounds based on solubility and permeability19,20, cannot be used to identify compounds that may penetrate Gram-negative bacterial membranes19,21. Indeed, while many drugs conform to the Ro5, various antibiotics, such as tetracyclines and rifampicin, lie outside these guidelines22,23, highlighting the distinct property space occupied by antibacterial agents compared to other drug classes.

Despite the value of HTS for synthetic small-molecule antibiotic discovery, these approaches yield active compounds (hits) at rates lower than 0.1%17,24,25. Similarly, the discovery rate of natural antibiotic molecules is very low as the same compounds are often rediscovered or discarded due to undesirable properties. Whether from natural sources or chemically synthesized, active compounds (hits) are logically followed by the subsequent process, lead generation or “hit-to-lead.” Lead generation involves the synthesis of hit analogs (hit expansion) by medicinal chemistry and structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies. These steps are conducted iteratively with toxicity assays in eukaryotic cells to improve the functional properties of the newly synthesized compounds26. Other key steps include identifying the binding target, MoA, and in vitro absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) assays. Hits that pass these filters are considered leads26, but only 5% of the initial hits are converted to leads27. The subsequent steps, lead optimization and preclinical development with in vivo animal models to advance leads into antibiotic candidates, also have a high attrition rate12. Overall, the success rate of small-molecule antibiotic discovery can be as low as 10−6, as estimated from the historical number of actinomycetes natural products that resulted in clinically useful antibiotics7. Clearly, these widely implemented approaches that have been successful to some extent in the past necessitate innovative solutions to alleviate the current limited supply of effective antibiotics.

Learning from the past to accelerate the future

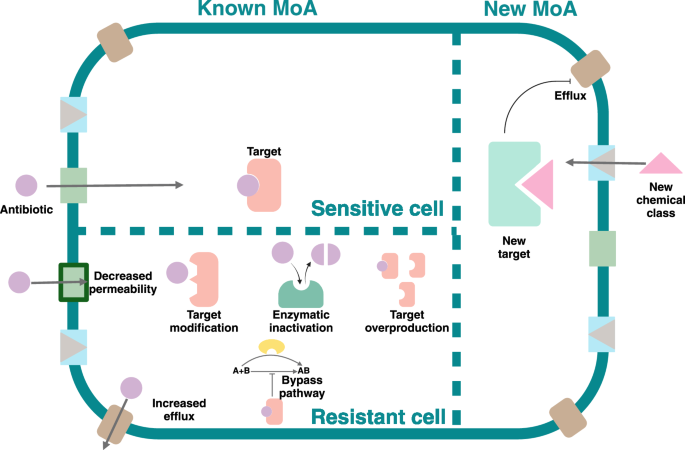

In the analysis of innovative approaches that can speed antibiotic discovery, we emphasize the interconnection between three innovation criteria established by the WHO: new targets, new classes, and new MoAs, as all are intended to reduce the likelihood of cross-resistance, which is the fourth criteria established by the WHO (Fig. 1). A novel target will most likely act on a previously unexploited biological vulnerability in pathogens, with a lower chance of encountering a previous resistance mechanism. Similarly, a new chemical class introduces a unique molecular structure, which reduces the possibility of being exposed to mechanisms of resistance developed against other antibiotic classes. Moreover, a new MoA enables targeting distinct biochemical processes, further lowering the risk of overlapping resistance pathways. Together, these factors can synergistically contribute to the absence of cross-resistance, ensuring effectiveness against MDR pathogens. Therefore, the four innovative criteria established by the WHO are directed to drive antibiotic discovery that effectively addresses current antibiotic resistance mechanisms. While the WHO report evaluates innovation in approved antibiotic drugs, we use the innovation concept applied to early antibiotic discovery, mainly fulfilled by the academic sector. We define innovation as an original approach or solution that has the potential to address the unmet need for more and more effective antibiotics”.

Created in https://BioRender.com.

Innovation 1: novel chemical classes of antibiotics

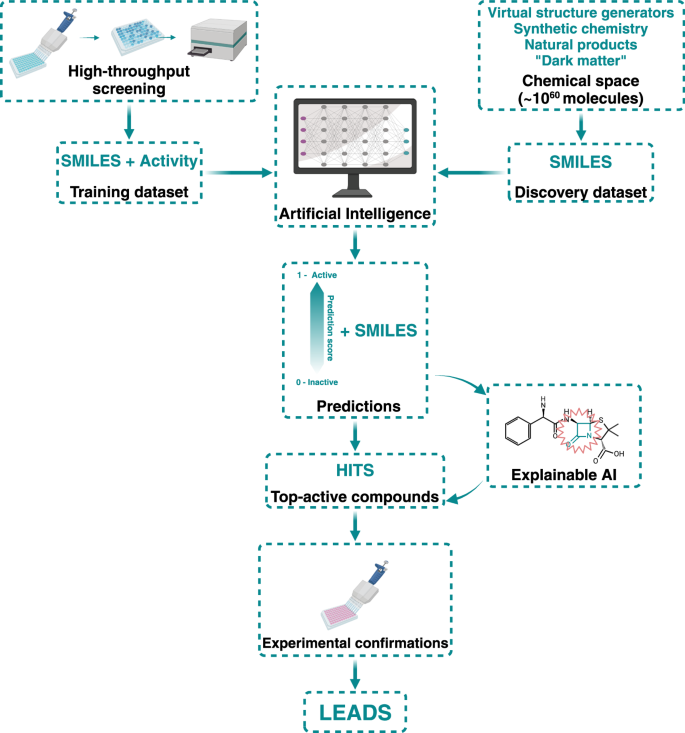

The scarcity of novel classes of antibiotics is being alleviated by the expansion of chemical space—the realm of all possible chemical compounds—driven by advancements in virtual structure generation, synthetic chemistry, and natural product discoveries. Although millions of chemical compounds have been employed in HTS campaigns looking for antibacterial molecules, these numbers do not compare with the current chemical space available for drug discovery. Thanks to explorations of “dark matter“28,29, combinatorial chemistry progress30, purchasable small molecule libraries31 and building blocks32, the number of chemical compounds that could be screened is estimated to be approximately 1060, suggesting that more antibacterials could be discovered if the complete chemical space is screened. While the costs and resources necessary for experimentally addressing the therapeutical potential of the current chemical space make this effort unfeasible, the latest artificial intelligence (AI)33,34 developments can leverage the wealth of data generated by previous HTS approaches, as these datasets can train AI models to predict antibacterial activity in vast virtual small molecule libraries. As more compounds are virtually screened for activity, the hit rate is expected to increase if the experimental (wet) screen is performed on compounds predicted to be active by the AI models35 (Fig. 2).

Machine learning uses the information gathered by HTS as training datasets to predict activity in larger and more complex datasets in the ever-expanding chemical space. These predictions are then experimentally tested to find leads and feedback into the process’s training step. xAI is also used to analyze the hits’ structure and gather valuable information about their probable MoA. Created in https://BioRender.com.

Machine learning, a type of AI, is well-suited for predicting the biological activities of small molecules34. Machine learning works by creating predictive models from data. In supervised machine learning, drug screen datasets used for training the computational models are either binarized (e.g., active vs. non-active) or given continuous labels (e.g., IC50 values) according to their experimentally confirmed biological activity. Then, the labels are linked to small molecules to build predictive models that can infer activity from chemical structure. Machine learning can also find hidden patterns in unlabeled datasets, which can be performed with unsupervised approaches33,36.

Deep learning is a subfield of machine learning in which neural networks are used to model complex unstructured datasets, such as representations of chemical structures. Deep learning uses neural networks to recognize distinct patterns in complex datasets and detect patterns automatically. To describe the small molecule’s chemical structure in a machine-readable notation, SMILES (simplified molecular-input line-entry system) strings can be used to train an algorithm to “learn” to identify features responsible for biological activity. In addition, graph convolutional networks (GCNs)37 can also describe molecules with graphs where nodes and edges represent atomic (atomic number, formal charge, chirality, etc.) and bonding (bond type, conjugation, ring membership, etc.) information, respectively. This information is passed along the graph’s edges from node to node to generate computationally usable molecule-level representations. This type of GCN is called directed-message passing neural network (D-MPNN)38, and its utilization has been a breakthrough in predicting bioactivity from chemical structures.

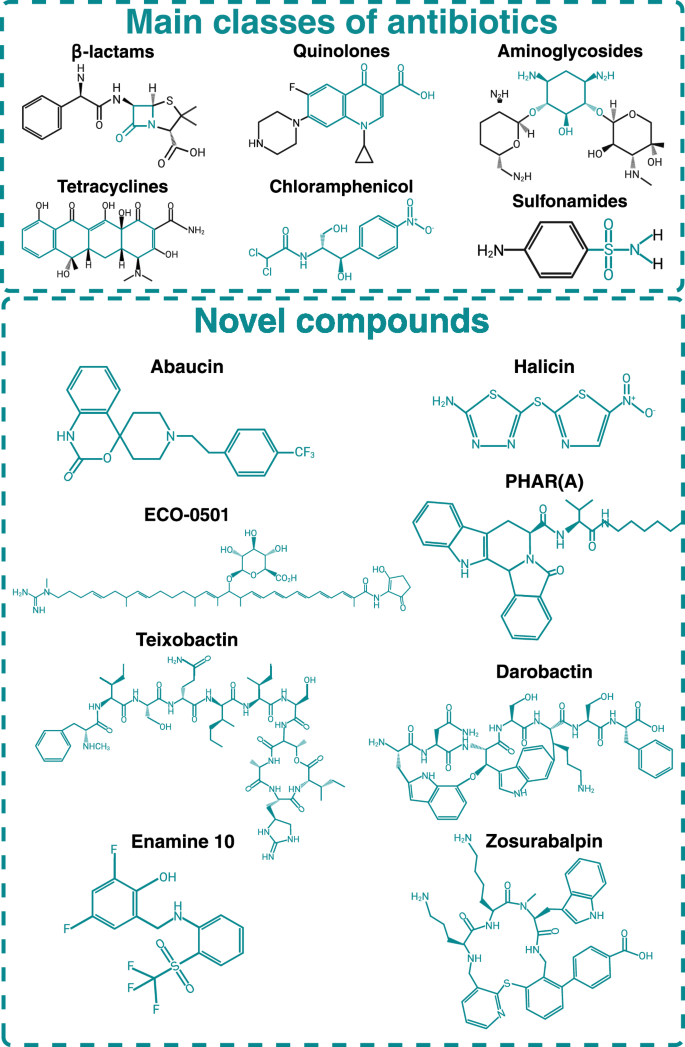

The JJ Collins laboratory was the first group that established D-MPNN-based deep learning models to predict antibacterial activity in small molecules and discovered Halicin39. Structurally distinct from existing antibiotics (Fig. 3), Halicin is active against a broad spectrum of pathogens, including multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii, and its unique chemical structure likely contributes to the absence of pre-existing resistance. Building on this success, Liu et al. rediscovered RS102895, a selective antagonist of the CCR2 receptor, as abaucin (Fig. 3), an antimicrobial molecule with a narrow spectrum of action against A. baumannii40. Similarly, after in silico screening of the ZINC library of natural products with a deep learning model trained on an HTS against Burkholderia cenocepacia, Rahman et al.35 identified PHAR261659 and its stereoisomer STL529920, later named PHAR(A) (Fig. 3), as bacterial growth inhibitors of a novel class. These examples demonstrate the potential of AI models for identifying chemical structures that can expand the chemical classes of antibiotics. While it is premature to anticipate if halicin, RS102895 or PHAR(A) will become novel antibiotic drugs, AI-driven in silico screens followed by experimental validations can open explorations of new chemical space that may lead, in the future, to the approval of antibiotics of novel chemical classes.

The bluish-green color shows the conserved structure between a specific class. The presence of novel chemical motifs in new molecules helps them avoid established mechanisms of bacterial resistance. Created in https://BioRender.com.

While current AI-driven models for property prediction show promise41, the black-box nature of the neural networks challenges the understanding of AI-related predictions. An emerging field of AI, explainable AI (xAI), provides predictions and offers insights into the reasoning behind those predictions. For example, MEGAN (a multi-explanation graph attention network)42 can help understand which chemical properties or substructures are most significant in the model’s predictions helping to identify substructures relevant for bioactivity. In addition, generative models like SyntheMol are capable of computationally generating structurally novel, synthesizable molecules with antibiotic activity43. This shift toward generative modeling empowered tools was employed by Wong et al. to discover two structurally novel antibiotic molecules against Staphylococcus aureus44. Moreover, xAI has also proved valuable for pre-filtering compounds with undesirable properties, such as colloidal aggregation45. In summary, AI approaches are expected to inform many physicochemical properties in small molecules if training datasets are available or generated. Similarly to exploring the vast chemical space, exploring microbial genomes and growing previously uncultured microbes can render natural products of novel classes. By capturing, prioritizing, and expressing biosynthetic gene clusters, Libis et al. identified ECO-050146 a small molecule related to conkatamycin47 (Fig. 3). Focusing on unculturable microbes, Ling et al. screened extracts from 10,000 isolates for bioactive compounds against S. aureus. This effort yielded teixobactin, a metabolite from Eleftheria terrae (Fig. 3). Teixobactin is active in vivo and has been shown to inhibit cell wall synthesis by interacting with precursors of cell wall biosynthesis, lipid II, and lipid III29. Although teixobactin was largely inactive against Gram-negative pathogens, it displayed exceptionally potent activity against Gram-positives, including S. aureus, Clostridioides difficile, and Bacillus anthracis29.

The examples presented here illustrate the prospects of an emerging era of antibiotic discovery based on new chemical classes. The increasing wealth of chemical space available and AI-driven HTS approaches have been demonstrated to increase the previously discouraging hit rates, reducing the likelihood of finding non-specific interactions, aggregating hits, and bringing more small molecules as starting points of antibiotic drug discovery. In parallel, the power of metagenomic and genomic explorations looking for novel biosynthetic gene clusters can address the issue of dereplication as the starting point for natural product discovery is shifting from phenotypic screening of extracts to the explorations of novel genetic elements in microbial genomes and metagenomes.

Innovation 2: new targets

Expanding antibiotic targets is crucial for addressing the growing challenge of antimicrobial resistance. By targeting bacterial processes that are essential for their survival but distinct from humans, researchers can develop antibiotics that remain effective even against MDR strains. While rational and systematic, the target-based approach for antibiotic discovery has suffered notable shortcomings, particularly when focusing on in vitro assays to find active compounds against a purified target. This limitation arises because identifying and inhibiting a target in vitro does not guarantee that the compound will effectively traverse the complex bacterial cell envelope or evade efflux pumps in a live infection environment. For Gram-negative bacteria, in particular, the outer membrane serves as a remarkable barrier, reducing the permeability of many molecules and facilitating efflux. Despite these challenges, recent progress in structural biology and genomics offers a promising pathway to overcome past limitations, enhancing target-based antibiotic discovery48.

One way to overcome the formidable barrier of the Gram-negative cell wall is to target outer membrane molecular components. The essential outer membrane protein BamA49, which is part of the Gram-negative β-barrel assembly machinery (BAM), is one example recently explored as an antibacterial target due to its cellular location and conservation across Gram-negative bacteria. Several inhibitors targeting BamA have been identified50, highlighting the druggability of this target despite the lack of a catalytic center. The discovery of darobactin (Fig. 3), a natural peptide produced by bacterial symbionts of nematodes51 and the generation of darobactin-resistant mutants of bamA led to the further structural analysis to identify the lateral gate of BamA as the binding pocket by of darobactin52. Indeed, darobactin binding blocks the interaction between BamA and the β-signal binding site, a conserved C-terminal motif in the β-barrel outer membrane proteins interacting with BamA. Other BamA-interacting small molecules have been discovered that target BamA. By screening a peptide library against the Escherichia coli purified BamA and the intact BAM complex, followed by minimal inhibitory concentration assays (MIC), Sun et al. identified two peptides. With a MIC of 5.3 µg/mL, PTB1-1 binds the extracellular leaflet region of the outer membrane, interacting with multiple extracellular loops of BamA in its close state. PTB2, instead, is an open-state inhibitor of BamA, which binds within the central lumen of the BamA β-barrel. PTB2 has an MIC of 4 µg/mL against E. coli but is not active against other ESKAPE pathogens. Overall, BamA-inhibitor interphases are defined by backbone interactions, which suggest that more than one point mutation may be necessary to disrupt the binding and confer resistance. Indeed, darobactin mutant strains were isolated at a low frequency (8 × 10−9) and presented more than one point mutation51. However, single BamA mutations (E435K and A499V) conferred increased E. coli resistance to the antimicrobial peptide by 2-fold53. While these mutations changed amino acids located in an extracellular loop of BamA, it is unclear if those amino acids were involved in backbone interactions, highlighting the need for more structural investigations of BamA in complex with inhibitory small molecules to validate this promising new target further.

Novel antibacterial targets can also be uncovered with their inhibitory, cell envelope-penetrating compounds by systematically perturbing bacterial genes and screening for chemical susceptibilities. Guided by this principle, Johnson et al. employed a chemical-genetic approach in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)54 to identify a novel bioactive molecule, BRD-8000, targeting the efflux pump EfpA. Subsequent chemical optimization produced BRD-8000.3, a potent compound effective against non-replicating, drug-tolerant Mtb—a critical challenge in tuberculosis treatment55. Additionally, BRD-9327, another compound discovered in this study, works synergistically with BRD-8000.3, offering the potential for combination therapies against Mtb. These findings underscore the potential of chemogenetic profiling in uncovering novel antibiotic scaffolds and MoAs. Chemical-genetic approaches can be followed by the latest developments in structural biology to explore the novel targets further. Using Cryo-EM, Li et al. further explored EfpA of Mtb as a new target for antibiotic discovery56. They presented the cryo-EM structures of EfpA in complex with lipids or the efflux pump inhibitor BRD-8000.3. Besides EfpA increasing resistance to multiple drugs, its transmembrane location and its essential role as a lipid transporter make this protein an enticing drug target. However, it should be noted that efforts to develop efflux pump inhibitors against EfpA should consider the risk of off-target effects observed in other compounds with similar function57.

Chemical genetics can find novel targets at the genome level with transcriptomics or knockdowns that represent the essential genome of a bacterium. For example, PerSpecTM compared transcriptional profiles of P. aeruginosa cells exposed to antibiotics with those of target knockdowns. Performing comparative functional profiling, PerSpecTM identified the targets of three antipseudomonal compounds: PA-0918, PA-69180, and PA-5750. In another effort, Rahman et al. created CIMPLE-seq, a rationally designed CRISPRi library of essential genes, which they employed to characterize the MoA of PHAR(A), a compound with a novel chemical scaffold and growth inhibitory activity against ESKAPE pathogens35. The effort led to the identification of PHAR(A) as an inhibitor of the peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase (Pth)58, a highly conserved bacterial essential protein required for recycling peptidyl-tRNAs during protein synthesis56,59. As PHAR(A) is the first small molecule found to inhibit Pth, further studies are needed to validate Pth as an antibacterial target.

Identifying bacterial essential molecular components and compounds that can inhibit their function does not automatically classify the bacterial molecular component as a “target.” Target identification should be based on several characteristics beyond essentiality and conservation across microbial genomes. Further prioritization should include absence in humans, metabolic role, and druggability. Such rankings can be achieved through specialized platforms like Target-Pathogen60,61. Upon selection of a suitable target with Target-Pathogen, virtual (in silico) drug screening can follow to identify small molecules that will likely bind the target62. Virtual drug screening is based on quantitative SAR, which models the correlation between the molecular descriptors of a compound and its biological activity63. In silico drug screens rely on (1) target structural information, including the location of the binding site on the target biomolecule, and (2) chemical descriptions of the compounds, which are numeric representations of the compounds’ molecular properties derived from their 3D structures64. For example, Post et al. employed a target-based design to improve the activity of Promysalin, which targets the P. aeruginosa succinate dehydrogenase (Sdh)65. Finally, target-centered approaches to antibiotic discovery can be significantly enhanced by leveraging a detailed understanding of the rules governing cell envelope penetration in bacteria. Recognizing these unique needs, the Hergenrother group analyzed 180 diverse small molecules to identify the physicochemical properties that facilitate cellular entry and successfully transformed antibiotics previously effective only against Gram-positive bacteria to achieve broader bioactivity against Gram-negative pathogens66,67,68. By elucidating the physicochemical properties that enable small molecules to penetrate these barriers—such as size, polarity, charge, and lipophilicity—one can envision the design of antibiotics that are potent against specific targets and capable of reaching them within the bacterial cell. By combining this knowledge with HTS against targets and rational optimization based on cell envelope penetration rules, target-centered approaches can overcome historical limitations, paving the way for the discovery of effective, cell-permeable antibiotics.

Innovation 3: new MoA

Introducing antibiotics with a new MoA is crucial for prolonging the effectiveness of the antibiotic arsenal. A novel MoA can bypass existing resistance mechanisms, making it harder for bacteria to survive and proliferate. This is particularly important in slowing down the emergence of resistance, thus extending the useful life of new antibiotics. One key example is SCH-79797, an antibiotic discovered using an unbiased, whole-cell screening strategy using a mutant E. coli lptD4213 with a compromised outer membrane. The screening yielded SCH-79797, a human PAR-1 antagonist69, as the most potent bioactive. SCH-79797 is composed of a pyrroloquinazolinediamine group linked to an isopropylbenzene moiety. Growth inhibitory property characterization of SCH-79797 demonstrated potent antibiotic activity against several clinically significant Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens. In-depth characterization of chemical moieties revealed that SCH-79797 kills via a dual mechanism; the pyrroloquinazolinediamine moiety targets folate metabolism, whereas the isopropylbenzene group disrupts membrane integrity70. Another notable example is zosurabalpin (Fig. 3), which targets carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii through a target that no previously FDA-approved drugs hit71. Zosurabalpin disrupts the transport of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) by inhibiting the LptB2FGC protein complex72, an essential system responsible for delivering LPS to the bacterial surface to construct the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. By blocking this process, zosurabalpin causes LPS to accumulate to toxic levels inside the cell, ultimately resulting in bacterial death.

While peptidoglycan and steps of peptidoglycan metabolism73 have been largely targeted with small molecules for antibiotic action74, new MoAs can be found in compounds directed to different and unexplored steps in peptidoglycan synthesis and turnover. Two such examples are corbomycin75 and clovibactim76. Corbomycin is a glycopeptide purified from Streptomyces sp. WAC01529 after identifying its biosynthetic gene cluster by an elegant phylogeny-guided approach that looked for divergent biosynthetic genes together with distinct self-resistance genes75. Once purified, corbomycin demonstrated MICs from 0.5 to 4 µg/mL against Gram-positive bacteria, including methicillin and daptomycin-resistant S. aureus. Similarly to other glycopeptides, the group determined that corbomycin targets peptidoglycan metabolism. However, they demonstrated that the affected step was downstream transglycosylation by measuring peptidoglycan intermediates. Other indications of a new MoA were the lack of synergy with other cell wall and membrane-active compounds and distinct phenotypes of corbomycin-exposed Bacillus subtilis cells. While resistance development was low (frequency of resistance less than 10−9), mutations in evolved B. subtilis-resistant strains were identified in a broad range of autolysin and autolysin regulation genes after exposure to the compound. Finally, corbomycin was found to bind the peptidoglycan in a dose-dependent manner. These results suggest that corbomycin binds peptidoglycan, impeding the action of autolysins and consequently inhibiting growth75.

Clovibactin was also discovered by innovative cultivation of microbes that were missed from standard methods76. Purified from the β-proteobacterium E. terrae cultures, clovibactin’s structure resembles that of teixobactin29. Clovibactin exhibits strong bactericidal activity against Gram-positive bacteria and a very low spontaneous resistance frequency (less than 10−10). By following the incorporation of labeled precursors, Shukla et al. found that clovibactin specifically interfered with the incorporation of radiolabeled N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) into the cell wall. To narrow down the steps within the cell wall biosynthesis pathway, the group used a two-component system-based reporter known to respond to antibiotics targeting lipid II biosynthesis. Further testing activities with purified enzymes and substrates in the lipid II biosynthesis pathway showed that clovibactin’s primary target is inhibited steps that used undecaprenyl-pyrophosphate-containing molecules lipid I and lipid II or undecaprenyl-pyrophosphate, suggesting that its MoA was through undecaprenyl-pyrophosphate binding and not enzymatic inhibition. Using state-of-the-art solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, the group could investigate the three-dimensional structure and dynamics of the interaction near-native conditions to show that clovibactin binds through an unusual hydrophobic interphase or a “cage” binding motif that makes the compound extremely robust to resistance development76. Confocal and atomic force microscopy further demonstrated that clovibactin assembles in supramolecular structures that enable stable binding of lipid II and other cell wall precursors blocking cell wall synthesis.

Finally, new MoAs can happen when novel chemical scaffolds are directed to novel targets. A prime example is Debio-1452-NH3, derived from the antibiotic deoxynybomycin through a machine learning-guided approach. While deoxynybomycin exerts antibiotic activity by inhibiting DNA gyrase in Gram-positive bacteria67, Debio-1452-NH3 targets the enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (FabI), a crucial enzyme in fatty acid elongation. The authors employed predictive models to enhance the compound’s permeability, broadening its bioactivity spectrum. While the original deoxynybomycin was active only against Gram-positive bacteria66, Debio-1452-NH3 demonstrated potent antibiotic activity against a wide range of Gram-negative pathogens. Furthermore, it effectively rescued mouse models from lethal infections caused by ESKAPE pathogens77.

Innovation 4: absence of cross-resistance

New antibiotics can be rationally re-designed for modifications that avoid emerging resistance to the previous drug. These new generations of existing classes of antibiotics address the immediate and crucial need to overcome clinical resistance. A remarkable example is cefiderocol, a siderophore of cephalosporin that uses the bacterial iron uptake system to enter cells, bypassing common resistance mechanisms and demonstrating low cross-resistance with other β-lactams78,79,80,81. Also, plazomicin, a next-generation aminoglycoside derived from sisomicin, incorporates synthetic modifications that allow it to bind a different site of the bacterial ribosome compared to older aminoglycosides82. These chemical alterations enable plazomicin to bypass nearly all clinically relevant resistance mechanisms, primarily those mediated by aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes83. Plazomicin is effective against clinically relevant drug-resistant bacteria, including Enterobacteriaceae, P. aeruginosa, and methicillin-resistant S. aureus84,85. While cefiderocol and plazomicin received approval from the US agency Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections86, Achaeogen, the drug development company behind plazomicin, went bankrupt87, highlighting the current paradox in antibacterial drug development9,88 when antibiotics are reserved for the most severe cases to prevent the rise of new antibiotic resistance. We conclude that decreasing the chance of rapid selection of new resistance mechanisms seems as important as avoiding cross-resistance with current antibiotics. The development of such resistance mechanisms can be minimized by seeking compounds that have multiple effects, targeting more than one molecular element or combining single-target antibiotics that have additive or synergistic mechanisms. While beyond the scope of this review, the polypharmacology approach to antibiotic discovery is promising and has been described extensively elsewhere89.

Beyond early discovery

Innovative approaches in early antibiotic discovery have the potential to expand the repertoire of promising candidate antibiotics, creating new opportunities for drug development. However, the path to clinical investigations, regulatory approvals, and commercialization remains filled with significant challenges. Developing new antibiotics is an expensive endeavor, with research and development (R&D) costs often exceeding $1 billion90. Unlike drugs for chronic conditions, antibiotics are typically prescribed for short-term treatments, making them less profitable. As a result, many pharmaceutical companies have shifted their focus to more lucrative therapeutic areas, such as oncology, leading to a decrease in new antibiotic development. Between 2010 and 2014, the FDA approved only 6 new antibiotics, a sharp contrast to the 19 approvals between 1980 and 198491. By the end of 2019, the number of active Investigational New Drug (IND) applications had fallen to an 11-year low, with the number of antibacterial INDs initiated between 2010 and 2019 being the lowest in the past three decades92. This stagnation has worsened the global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis, underscoring the urgent need for innovation in antibiotic development.

Efforts to address these challenges have concentrated on reducing the financial risks associated with antibiotic development, particularly market and reimbursement/competition risks. Market risk arises from the low profitability of antibiotics, which are used sparingly to preserve their efficacy, while reimbursement issues stem from price controls and competition from cheaper generics. Legislative measures like the Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Act have sought to incentivize development by extending market exclusivity, expediting FDA approvals, and waiving fees93. While these measures have led to some incremental innovations, they have largely failed to produce novel antibiotic classes94. The 21st Century Cures Act introduced the Limited Population Antibacterial Drug (LPAD) pathway to streamline antibiotic approvals targeting small, high-risk populations95. While this approach reduces clinical trial costs, its narrow scope limits broader applicability, and smaller trials will have less statistical power to identify efficacy and safety issues.

Countries are experimenting with innovative approaches to address these challenges on a global scale. The United Kingdom (UK) became the first country to implement a fully delinked pull incentive through a pilot subscription model96. Under this program, the UK pays pharmaceutical companies (Pfizer and Shionogi) a fixed annual fee of £10 million for 3 to 10 years for access to two antibiotics, ceftazidime with avibactam and cefiderocol, respectively97. Payments are based on the value of the drugs to the healthcare system rather than their sales volume. This model guarantees developers a stable revenue stream, ensuring access to these antibiotics while aiming to make R&D in this sector more attractive. Although the model holds promise for encouraging innovation, it is too early to assess its long-term impact on antibiotic R&D.

The success of the UK model has sparked similar global initiatives. Since 2022, G7 nations, including Japan, Canada, the United Kingdom, the European Union (EU), and the United States, have been implementing various strategies to combat AMR. For example, the UK is considering scaling up its subscription model, while Japan has introduced a revenue guarantee program for novel antibiotics starting in 202398. Germany has proposed revised pricing and reimbursement laws (ALBVVG) for reserve antibiotics99 and pledged €50 million to the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP)100. The US has committed up to $300 million for CARB-X101, and Canada has pledged support for SECURE, a collaborative initiative by GARDP and WHO102. France has launched a national strategy to combat antibiotic resistance, emphasizing innovative R&D and improved drug evaluation principles103, while Italy has introduced its second National Action Plan on AMR104.

In the US, the Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions to End Upsurging Resistance (PASTEUR) Act represents another effort to address market and reimbursement risks105. Reintroduced to Congress in April 2023, the Act proposes subscription-based contracts between the federal government and pharmaceutical companies. These contracts would provide predictable, upfront payments for antibiotics that address critical public health needs, irrespective of their usage levels. By decoupling revenue from sales volume, the PASTEUR Act aims to make antibiotic development financially viable, even for drugs used sparingly. However, like the UK model, it does not address the scientific challenges of antibiotic discovery, such as identifying novel compounds, high failure rates in clinical trials, and limited knowledge of resistance mechanisms (Table 1).

The financial challenges of antibiotic discovery are crucial, but the scientific difficulties are equally significant. Over the past two decades, the AMR field has steadily lost vital research talent due to the retirement of experienced scientists, many of whom have not been replaced due to limited opportunities in the sector106. This “brain drain” has led to a growing knowledge gap, with young scientists increasingly reluctant to enter infectious disease research due to the lack of incentives107. Addressing this gap requires sustained investment in education and training to revitalize the field. However, even with policy interventions like pull incentives to attract private investment, the loss of expertise and infrastructure in the AMR field could hinder progress for years to come, leaving the world with few researchers capable of delivering the necessary innovations to combat the problem.

To tackle the scientific risks associated with antibiotic development, substantial investments in early-stage research are needed, along with fostering academic-industry collaborations and supporting initiatives focused on novel antibiotics. Non-profit organizations, such as the Pew Charitable Trust’s SPARK (Shared Platform for Antibiotic Research and Knowledge)108, work to bridge the gap between academia and industry by creating shared knowledge platforms109. Collaborative frameworks like the Transatlantic Task Force on Antimicrobial Resistance (TATFAR)110 have streamlined regulatory requirements for clinical trials. Yet, disparities in funding and prioritization among nations continue to hinder global progress.

The AMR crisis calls for a multifaceted response that balances financial incentives with scientific innovation. Legislative measures such as the GAIN93 and Cures Acts95, the PASTEUR Act105, and the UK subscription model96 represent significant advancements, but their success depends on effective implementation, global coordination, and sustained commitment. The transformative breakthrough of penicillin reminds us that meaningful progress in this field requires bold, innovative solutions, not just incremental steps. A coordinated effort among governments, industry, and academia is crucial to revitalizing the antibiotic pipeline and ensuring that antibiotics remain a cornerstone of modern medicine.

Conclusion

Guided by the innovation criteria established by the WHO, we underscore how recent advances in predictive biology are transforming the early antibiotic discovery field. These advances enable a synergistic integration of past efforts by combining the broad exploratory potential of HTS campaigns with the precision and specificity of structure-based drug design. We predict this dual approach will enhance the identification of promising compounds and streamline their optimization, bridging the gap between large-scale discovery and targeted innovation. The global effort to combat antimicrobial resistance, innovation in early antibiotic discovery, and cooperation to address regulatory and commercialization issues must continue to provide sustainable solutions to address the growing threat of MDR pathogens and secure the future of effective antibiotics.

Responses