Emerging antimicrobial therapies for Gram-negative infections in human clinical use

An increasing need for novel therapeutics

Antimicrobial bacterial resistance poses an increasing threat to public health and modern medicine practices to treat infection. In 2019, over 6 million deaths were associated with antibiotic-resistant bacteria1 and is predicted to increase to over 10 million deaths annually by 20502. In 2021, six species of bacteria caused over 100,000 deaths due to multi-drug resistance (MDR), four of which are Gram-negative including Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa3. Additionally, nine out of fifteen species in the 2024 World Health Organization (WHO) bacterial priority pathogens list are Gram-negative4. Such bacteria are especially problematic as they are intrinsically resistant to many antibiotics due to their outer membrane that can act as a physical barrier preventing cell entry and targeting of intracellular components for killing2. Additionally, many Gram-negative bacteria are quickly acquiring resistance to last-line antibiotics including carbapenems, third-generation cephalosporin, and fluoroquinolones. It is predicted that the development of new antimicrobials for specifically Gram-negative infections will avert 11.1 million deaths by 20502.

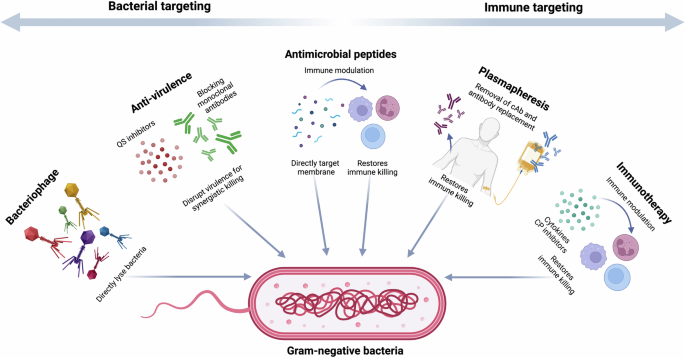

There has been a significant decrease in antibiotic discovery due to the inherent challenges in identifying or designing molecules with suitable pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles, coupled with the speed at which bacterial resistance can develop. These challenges are worsened by the lack of an economically viable pathway for the development of these drugs leading to many large pharmaceutical companies de-investing in antibiotic development5. In light of these issues, many novel antimicrobial therapies have been proposed that can be used in conjunction with existing standard care (Fig. 1). These include methods that directly target the bacteria, including, phage therapy (PT), phage-derived products, anti-virulence therapies, and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). Other potential therapies focus on re-activating or manipulating the host immune system to fight disease. This includes plasmapheresis therapy, immunotherapy, and the use of monoclonal antibodies.

QS quorum sensing, cAb cloaking antibodies, CP check point inhibitors. Created in BioRender. Ledger, E. (2025) https://BioRender.com/a99q275.

Many of these therapies have been shown to be efficacious against different Gram-negative bacteria in preclinical studies. However, the transition from laboratory results to use in the clinic can be a long and arduous process, with many promising therapies failing when trialed in human cohorts. Thus, to explore which of these therapies is most likely to be the next immediate step in treatment for MDR Gram-negative infections, this review focuses specifically on those treatments that have in-human data. This data is taken from therapies that are either (1) in clinical trials or (2) shown to be efficacious in treating infection through case studies of compassionate use.

Bacteriophage therapy

Bacteriophage (phage) therapy (PT) already has a wealth of clinical evidence of efficacy against MDR Gram-negative infections. As early as 1919, Felix d’Herelle successfully treated children suffering from bacterial dysentery with phage6. However, the introduction of broad-spectrum antibiotics lessened researchers’ interest in phage therapeutics, postponing the development of PT for clinical use. The emergence of MDR has reignited interest in PT due to its highly effective bactericidal properties. It also has other clinical benefits; PT can be highly specific to a single infecting species, avoids host microbiome disruptions, and has the potential to minimize the future emergence of MDR. Today, PT has been applied in clinical use, particularly in Eastern Europe. However, lack of clinical support and difficult regulations for therapies used in humans, hinder the establishment of PT as a widespread antimicrobial therapy against bacterial infections.

Models of phage therapy

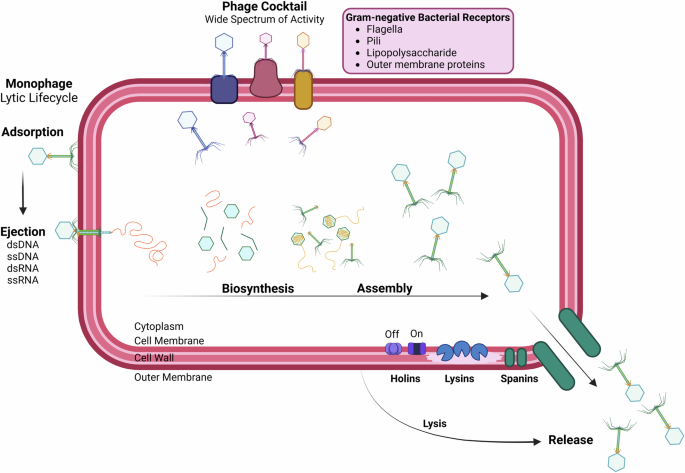

Bacteriophages are viruses that use bacteria as their host and are found in every explored biome, with an estimated overall abundance of 1031 7. Phages have a small genome but large genomic diversity and are divided into two types: lytic (virulent), and lysogenic (temperate) phages, with only lytic phages currently used in treatment of infection8. Bacteriophages are structurally diverse, but the most common morphology represented (in public databases) is dsDNA and connected to a tail (Caudovirales)7. Tail fibers, tail spikes, and tail tips promote the recognition of host cells for adsorption. Following recognition and adsorption, the phage genome is ejected into the host cytoplasm. The strictly lytic phage then utilizes host proteins to synthesize structural and enzymatic phage proteins. Cell lysis is induced by the activity of endolysins degrading peptidoglycan, and progeny phage is released9 (Fig. 2).

Phage adsorbs to the bacterial surface via receptors and ejects genetic material into the bacterial cell. Phage enzymes and structural components are synthesized by utilizing the host cells’ own metabolic machinery. Synthesized components assemble, and phage enzymes degrade the bacterial cell membrane. Lysis is induced when intact phages are released from the host cell for reinfection. Created in BioRender. Hickson, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/y11g164.

To treat bacterial infection using phage, a high concentration of either a single or a cocktail of multiple phages is given to the patient through various means depending on the site of the infection (Fig. 3). There are two predominant models of phage development for therapeutic use. First, phage cocktails can be formulated on demand based on the susceptibility of the patient’s specific isolate. In this model, clinical isolates are screened against phage banks, a collection of pre-characterized and usually locally isolated phages. There are many of these large phage-banks around the world, however, these processes are not broadly available and regulatory pathways are much less defined10. A successful regulatory model for on-demand PT has been implemented in Belgium, the Magistral Phage system with no case-by-case approval required allows for the production and use of personalized phage medicines11.

Created in BioRender. Hickson, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/x60i493.

The second model for development is traditional fixed-composition phage products designed to treat a specific pathogen or conditions12, allowing a clearer regulatory pathway. However, due to the static nature of the product, fixed-composition products cannot adapt to the emergence of new strains that circulate in patient populations12. In Russia and Georgia, phage cocktails are already available as over-the-counter drugs for treatment. Two half-year updated cocktails, Pyo and Intesti Bacteriophage, are available for treatment against bacterial infections13. Currently, the FDA has not approved any phage product for clinical use.

Bacteriophage therapy in compassionate use

Most clinical evidence regarding PT has stemmed from personalized therapy in cases for expanded access (or compassionate use). PT can offer an antimicrobial option when all other treatment options are exhausted and has been described as efficacious in a wide variety of infections including urinary tract infections (UTIs)14, rhinosinusitis15, skin and soft-tissue infections16, and acute respiratory infections. It has also been efficacious in biofilm-associated infections such as osteomyelitis17, cardiac device infection18, and respiratory infections in the setting of cystic fibrosis (CF)19. A wide variety of Gram-negatives have been successfully targeted including E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and A. baumannii, however overwhelmingly most case studies have been described against P. aeruginosa (Table 1). P. aeruginosa extensively produces biofilm, a challenge for current antimicrobial therapies. Synergistic bactericides have been investigated to combat problematic infections, such as using various compounds that can destroy extracellular polymeric substances and increase the permeability of biofilm. As suggested for OMKO1 phage that targets outer membrane porin M, can replicate within bacteria present in biofilm. As phage OMKO1 replicates, the biofilm is disrupted, and therapeutic concentrations of antibiotics can better reach target bacteria. Bacterial cells resistant to phage OMKO1 infection are expected to be more susceptible to antibiotics in the disrupted biofilm9.

Primarily, PT is administered intravenously but other common routes of administration in patients include systemic injection (e.g., intradermal, intramuscular, and subcutaneous), oral, and direct administration (e.g., topical, inhalation, and bladder irrigation)19. Administration route is often determined by site of infection, e.g., inhalation for respiratory infections and topical for burn wounds.

Despite the plethora of successful case studies published, confirming efficacy remains challenging due to heterogeneity in the administration, concentration of phage, number of phages (i.e., single versus cocktail), and duration of the therapy across studies. Publication bias should also be considered with reports of unfavorable outcomes being less likely to be published than those with favorable outcomes. Indeed, a recent retrospective study of 100 consecutive PT cases revealed that clinical improvement and eradication of the targeted bacteria were reported in only 77.2% and 61.3% of infections, respectively20. They also identified the importance of concurrent antibiotics for improved outcomes of the therapy. Thus, quality randomized controlled trials are vital to determine the efficacy and best practices for PT in the future.

Phage therapy in clinical trials

Well-designed clinical trials are vital to establish the efficacy of PT in human infection. This process is now well underway, with over a dozen commercial phage/ phage cocktails against Gram-negative bacteria for human use currently in phase I–III trials (Table 2). Many of the phase I and II trials focus on safety and tolerability, with few published results so far. Trials are for a variety of species, with P. aeruginosa again dominating. Multiple diseases are also being investigated, including lung infections, UTIs, irritable bowel diseases, and chronic wounds. Challenges for clinical use include safety (during lysis bacterial endotoxins and exotoxins are released), the narrow lytic spectrum of phages limits the clinical application (can be circumvented by combining phages in cocktails), and duration of efficacy as the immune system can produce phage-neutralizing antibodies, and bacteria can gain resistance to phage21. Problems that can arise from clinical trials of PT were highlighted by PhagoBurn, the first major trial under modern medicinal product regulatory standards in the EU. The manufacture of one batch of investigational products (12 and 13 phage cocktails against P. aeruginosa and E. coli, respectively) took 20 months to produce, costing the majority of the trial budget11. Cocktails could not be applied simultaneously for purpose of the study, thus patient recruitment was impaired due to common co-infections by these species. In the future, implementation of standardized practices would greatly benefit the advancement of PT research, such as the use of phage susceptibility testing, route of administration for infection types, or accessible databases for more efficient collection of PT data.

Future of phage-based therapies

Other antimicrobial therapies are being investigated in tandem with PT. A common therapy, fecal microbial transplant, involves the transplantation of fecal bacteria and other microbes from a healthy individual and is an effective treatment for Clostridioides difficile, a Gram-positive infection22. Interestingly, a clinical trial in early phase 1, is investigating the transference of fecal phage for enhanced gastrointestinal tract maturation in preterm infants (NCT05272579). Viruses and proteins are transferred from healthy term infants to preterm infants to enhance gastrointestinal tract maturation, with the long-term goal being to develop a safe and effective treatment to prevent the severe gut disease called necrotizing enterocolitis. The use of probiotics with bacteriophage is under investigation to improve urinary and vaginal health. PreforPro® product combines prebiotic (Bifidobacterium lactis)) and phage cocktail targeting E. coli (LH01-Myoviridae, LL5-Siphoviridae, T4D-Myoviridae, and LL12-Myoviridae23). Both prebiotics and phages have been investigated for their potential to modify the gut microbiota and clinical trials are currently underway to determine efficacy in human health (NCT05590195).

Thus, the application of PT has shown efficacy as an antimicrobial against MDR Gram-negative bacteria in human clinical settings. However, determining the limits to the efficacy of PT and standardization of practices is vital for its widespread adoption. Improvements, including combination therapies, engineered phage and development of phage products (e.g., lysins) are currently well underway24,25. Despite downsides such as the development of phage-neutralizing antibodies, risk of antibiotic resistance transference, and potential toxicity, it remains one of the most promising and immediate antimicrobial therapy avenues to combat MDR Gram-negative infections.

Antimicrobial peptides

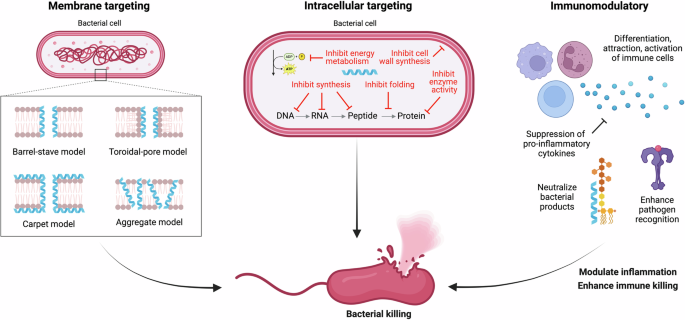

AMPs are naturally occurring small oligopeptides comprised of 10–50 amino acids that are involved in the innate defense of many living organisms, including humans, animals, and plants26. These peptides have rapidly gained interest as an alternative therapeutic to treat infection due to their broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity toward a wide range of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. Unlike antibiotics that mainly target intracellular processes, AMPs are considered less likely to induce resistance as they primarily act by directly disrupting cellular membranes26. There are four key structures of AMPs, including α-helical, β-sheet, extended, and cyclic that are composed largely of hydrophobic amino acids and positively charged residues27. This cationic and amphipathic nature of AMPs allows them to bind to negatively charged cell wall components and membranes leading to the formation of pores cumulating in microbial death26 (Fig. 4). However, some AMPs can act intracellularly to directly degrade nucleic acids, and interfere with protein synthesis, enzyme activity and metabolism affecting bacterial growth, biofilm formation and survival26 (Fig. 4). Additionally, peptides originating from vertebrates such as defensins and cathelicidins can exert immunomodulatory effects by activating, inhibiting and or recruiting immune cells offering broader infection control in humans (Fig. 4)26.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are often hydrophobic and positively charged, allowing them to interact with negatively charged bacterial membranes to form pores by multiple proposed models and lead to direct bacterial killing. AMPs can also target multiple intracellular processes such as transcription, translation and protein synthesis, enzyme function, energy production, cell division, and more resulting in direct bacterial death. Alternatively, these peptides can also modulate the immune system by recruiting and activating immune cells, neutralizing pathogen products, enhancing pathogen recognition, and killing cumulating in the resolution of inflammation and clearance of infection. Created in BioRender. Ledger, E. (2025) https://BioRender.com/c13i387.

The antimicrobial peptide database (APD3) currently contains over 4000 AMPs, including largely naturally occurring AMPs and over 300 synthetic peptides designed and created to improve AMP activity, stability, and production costs28. Of these peptides, 84% are characterized to target Gram-positive and or Gram-negative bacteria28. There are currently ten AMPs commercially available to treat bacterial infections; however, only three peptides are active towards Gram-negative bacteria27. Colistin (Polymyxin E) and Polymyxin B show potent membranolytic activity toward Gram-negative pathogens; however, are only clinically utilized as a last resort treatment due to their severe nephrotoxicity at antimicrobial relevant levels29. Gramicidin D has some activity towards Gram-negative bacteria; however, is primarily used in topical treatments for Gram-positive infections and cannot be utilized systemically due to toxicity29. The limited clinical use of available AMPs highlights the gap in the market and the requirement for novel non-toxic compounds that can treat key resistant Gram-negative priority pathogens.

AMPs in clinical trials

In contrast to PT, other than the peptides mentioned above, there are no published cases of novel AMPs being used for compassionate use. There are, however, approximately 15 broad-spectrum antibacterial AMPs currently undergoing clinical trials in humans to treat infections and disease processes often caused by Gram-negative bacteria (Table 3). PL-5 is a synthetically designed α-helical AMP with proposed membranolytic activity and is one of the most recent peptides to commence phase III trials as a topical spray for wound infections. Previous phase II trials reported that PL-5 spray was safe and was more effective at reducing skin infection rating scale scores and bacterial clearance was comparable to an active antibiotic drug control30. An additional phase II trial reported PL-5 to improve recovery speed of diabetic foot wounds31, however, the effectiveness of PL-5 for more serious wound infections is yet to be determined. The pore-forming peptide melimine derived from melittin is currently in phase III trials for the prevention of keratitis infection with extended-wear contact lenses. In phase II trials, contact lenses coated in mel4, a shorter derivative of melamine reduced the incidences of corneal infection; however, it did not reach statistical significance32. Phase III trials will continue to evaluate the efficacy of melimine or mel4 for prophylactic treatment, however, whether these peptides could be used to treat active infection remains unclear.

There are multiple peptides entering phase II or III trials that act by modulating the immune system to treat infection and related disease processes rather than acting to kill pathogens directly (Table 3). The peptide p2TA (Reltecimod, AB103) blocks antigen and endotoxin-mediated activation of T cells by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and thereby inhibits subsequent Th1 cytokine induction and tissue damage33. In a phase III trial, intravenous administration was proven safe and resulted in the improved resolution of organ dysfunction and hospital discharge status in necrotizing soft tissue infections33. Preliminary data from a phase III trial of another innate defense regulator reported that intravenous treatment with disquietude (SGX942) resulted in a 56% reduction in the duration of severe infected oral mucositis in patients receiving chemoradiation, however statistical significance was not reached. Additionally, the hormone-derived anti-inflammatory EA-230 peptide attenuated the systemic inflammatory response in an induced human endotoxemia model in a phase II clinical trial34. Whilst more recent trials are investigating the use of these AMPs in other inflammatory disease settings34, these peptides that have favorable safety profiles have the potential to aid in the resolution of MDR infections by modulating and enhancing immune responses.

One of the most extensively studied AMPs due to its diverse biological functions is the human cathelicidin LL-37, currently in phase II trials. LL-37 has been shown to directly form membranolytic pores, neutralize lipopolysaccharide (LPS), inhibit biofilm formation, and modulate immune responses including immune cell attraction35. Topical treatment enhanced the healing rate of diabetic foot ulcers; however, did not decrease the bacterial wound burden nor key IL-1α and TNF- α inflammatory markers in a phase II trial36. It was proposed that bacterial resistance, production of LL-37 degrading proteases by pathogens such as P. aeruginosa, and pre-existing complex biofilms may have limited the antimicrobial effect of the compound in such infections36. Further shorter derivatives with improved properties continue to be evaluated in vitro to enhance the therapeutic scope of LL-3735. OP-145 (P60.4Ac), a LL-37 derivative has completed phase II trials where ototopical drops showed a 47% treatment success for chronic infections of the middle ear, however no phase III trials have been proposed37.

There are six broad-spectrum AMPs that target bacterial membranes entering phase I clinical trials to assess their safety and tolerability in humans (Table 3). This includes the first AMP suppository PL-18 aimed to treat bacterial vaginosis, and tilapia piscidin 4 (TP4), melittin, omiganan (MX-226), and pexiganan (MSI-78) for topical treatment of soft tissue infections. Additionally, intravenous treatment with the cationic peptide WLBU2 (PLG0206) was proven to be safe and well-tolerated and projected for treatment of multiple microbial infections38. There are additional AMPs, including Exeporfinium chloride (XF-73), Lytixar (LTX-109), PAC113 (Nal-P-113), and hLF1-11 that are in trials for the treatment of Gram-positive infections however have broad antibacterial activity and the potential to be utilized for Gram-negative infections if proven safe and effective27,39.

Multiple AMPs have failed upon reaching phase II and III clinical trials due to safety concerns or lack of efficacy in humans (Table 3). The AMP Murepavadin (POL7080) demonstrated potent and specific activity towards P. aeruginosa in vitro; however, intravenous treatment in a phase III trial to treat P. aeruginosa pneumonia was terminated due to severe adverse events such as renal failure39. Another bacterial pore-forming protegrin-1 derivate, Iseganan (IB-367) failed to improve patient outcomes upon inhalation to treat ventilator-associated pneumonia40, and mouth washes failed to improve infection-related oral complications of radiation therapy41. Oral administration of a broad immunomodulatory AMP talactoferrin (TLF, rhLF) was associated with lower rates of nosocomial infections in treated infants in phase II trials42, however Phase III trials to treat severe sepsis were terminated due to increased mortality in treatment groups43. Pexiganan (MSI-78) was proved safe for the topical treatment of diabetic foot ulcer wounds; however, it refused FDA approval due to no additional benefit compared to conventional antibiotics44. Additionally, AMPs Omiganan (MX-226), Opebacan (rBPI21, neuprex), and XOMA-629 showed favorable safety profiles however failed to show clear efficacy in treating infection45. Omiganan (MX-226) and pexiganan (MSI-78) are recommencing phase I trials for the safety of topical treatments for soft tissue infections, however, the fate of these peptides for clinical use remains uncertain.

Future of AMP therapies

To date, few AMPs have made it to phase III trials in humans, highlighting the many chemical and biological challenges remaining for the clinical development of AMPs especially for Gram-negative bacteria. AMPs in current trials are mainly utilized as localized treatments, and failures in intravenous administration emphasize that toxicity remains a large limitation for the clinical utilization of these peptides. Various strategies are being investigated to overcome toxicity, such as peptide design aimed to exclude toxic structures28, encapsulating peptides in nanocarriers to reduce local toxicity46, and using AMP and antibiotic combinations to synergistically kill microbes and reduce the dosage of toxic peptides required29. Other difficulties with AMP efficacy and stability in vivo may be overcome through chemical modifications such as cyclization, PEGylation, branching, and d-amino acid substitution to improve biostability and lipidation to improve membrane interactions29.

AMP prediction and design remain especially challenging for Gram-negative bacteria where vast variations in LPS, such as lipid A charge and membrane lipid composition can impact peptide binding and activity between species47. Infections treated by peptides in current trials are often also dominated by Gram-positive pathogens, therefore the clinical efficacy of these broad-spectrum AMPs for strictly Gram-negative infections remains under characterized. While AMPs are proposed to be less likely to develop resistance due to their multifaceted targets compared to antibiotics, there are increasing reports of antimicrobial resistance to AMPs such as colistin by E. coli, Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumonia, and other Gram-negative bacteria48. Many of these pathogens can intrinsically carry the mcr gene that encodes a phosphoethanolamine transferase capable of modifying lipid A composition, thereby inhibiting colistin binding and activity49. However, there are up to 11 plasmids that can facilitate the horizontal gene transfer of the mcr-1 gene allowing the acquisition of colistin resistance48,50. Other mechanisms of resistance include AMP degradation by pathogen proteases36,51, efflux of intracellular targeting AMPs52, and cell surface alterations such as capsule synthesis lipid A acylation among others that could limit AMP efficacy51. Therefore, antimicrobial resistance has the potential to persist with the use of AMPs. One way forward to reduce resistance development may be the use of AMPs in combination therapy with other compounds or therapies.

The current utilization of combination therapy in humans is limited to the clinically approved AMPs colistin and polymyxin B in conjunction with antibiotics such as rifampicin, carbapenem, meropenem, tigecycline, and more. Many case studies or series have shown favorable clinical outcomes of colistin combination therapy to treat Gram-negatives such as A. baumannii53,54,55,56. However, a meta-analysis of 32 observational studies and randomized controlled trials highlighted that intravenous colistin combination therapy was not associated with lower mortality compared to colistin monotherapy to treat MDR Gram-negative infections57. In a recent trial of 464 participants, colistin in combination with meropenem was not superior to colistin monotherapy to treat Pneumonia and bloodstream infections with MDR A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacterales58. Additionally, a meta-analysis of polymyxin B revealed no difference in combination versus monotherapy to treat infection59. Despite this, many studies have demonstrated promising synergism of novel AMPs in combination with antibiotics to kill MDR Gram-negative pathogens in vitro and in vivo animal models60.

There continues to be a vast array of AMPs in vitro development, and over ten are currently in pre-clinical development with the potential to treat Gram-negative infections27,29,39,61. Whilst AMP development remains significantly challenging, advancements in the understanding of peptide function, development of AMP designing tools, chemical modifications and combination therapies may accelerate the efficacy of these potent peptides for treatment of MDR pathogens.

Therapies with limited in-human use data

Plasmapheresis therapy

In contrast to PT and AMPs, plasmapheresis therapy focuses on re-activating the immune system to eradicate infecting bacteria, regardless of their MDR status. Many bacterial infections can manipulate the host immune system to their own benefit promoting survival rather than their eradication. Plasmapheresis therapy is aimed at overcoming the phenomenon of antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of infection, where antibodies paradoxically promote disease, rather than protect against it62. ADE is best described against viral pathogens such as Dengue, where induction of specific antibodies can lead to an increase in viral load, replication, and inflammation, exacerbating disease. ADE has also been demonstrated against Gram-negative bacterial infections, albeit with a different mechanism of action62. In bacterial infections, antibodies specific for the O-antigen component of LPS have been shown to protect Gram-negative bacteria from killing by the complement system (i.e., serum killing). These ‘cloaking antibodies’ when in high titer and affinity, block complement-proteins inserting into the bacterial membrane and subsequent lysis63. Cloaking antibodies (cAbs) have been described in a wide array of Gram-negative infections including E. coli, P. aeruginosa, Burkholderia, Neisseria, Salmonella, and others64,65.

Importantly, cAbs have been shown to be associated with worse disease. In both E. coli urosepsis and P. aeruginosa bloodstream infections, cAbs have been found to be prevalent (20–35% of patients) and protect their otherwise serum-sensitive isolates from complement killing in the blood66,67. In patients with chronic lung infections of P. aeruginosa those with cAbs had significantly worse lung function68. In those post-lung transplants, the presence of cAbs was associated with worse outcomes in both mortality and chronic lung allograft dysfunction69.

As the removal of cAbs had been shown to restore the complement killing of bacteria in vitro70, plasmapheresis was proposed as a novel salvage therapy to treat MDR P. aeruginosa infection. This therapy, which separates the plasma from blood cells followed by supplemental IVIg, has been used on three patients to remove cAbs. In all cases, this led to patients’ sputum becoming P. aeruginosa negative and clinical improvement71,72. Two patients had further rounds of plasmapheresis after cAb titers re-increased leading to a similar reduction in bacterial load and increase in health. This treatment has only been used for compassionate use thus far, and many questions remain about its efficacy. Like PT above, efficacy is hard to determine without high-quality clinical trials, due to the concurrent use of antibiotics, supplementation with IVIg, and variable settings in these case studies. However, the high prevalence of cAbs in some infections, its prevalence across multiple Gram-negative species, and the fact that plasmapheresis is already used clinically for other conditions means that the treatment may be useful in the future.

Anti-virulence therapies

Anti-virulence therapies, in contrast to antibiotics, focus on counteracting, changing regulation of, or inhibiting aspects of bacterial virulence without necessarily leading to the killing of the bacteria. By targeting virulence, it can prevent the bacteria from causing severe disease or in many cases, make them more susceptible to existing antibiotics. Excellent reviews of the benefits of anti-virulence therapies exist, highlighting their success in a variety of pre-clinical models73. However, despite the many different proposed therapies only a handful have been used in cases of human infection.

Many anti-virulence therapies aim to inhibit or reverse biofilm production by targeting the signaling system that regulates these phenotypes; quorum sensing (QS). Azithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic with a broad but shallow bactericidal range, that is also found to decrease QS in P. aeruginosa infections, as well as reduce inflammation74. A trial of a sub-inhibitory concentration of azithromycin in patients with chronic P. aeruginosa infection found it associated with improvements in health outcomes, including fewer exacerbation events. A further trial investigated the use of azithromycin to prevent P. aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). Although a significant reduction in VAP was not reached, it did significantly prevent VAP in those patients at high risk of rhamnolipid-dependent VAP75. Other macrolides have been shown to improve outcomes in patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infections, however whether this is due to anti-virulence, or anti-inflammatory properties is unknown76,77. Finally, garlic has also been investigated to determine if it can improve health in patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infections, due to its QS inhibition properties. This small trial, however, did not find any difference in test and placebo groups78.

A further anti-virulence strategy that has progressed to clinical trials focuses on blocking the action of the P. aeruginosa Type 3 Secretion System (T3SS), vital for the pathogenicity of this species. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that target the needle tip protein of the T3SS, PcrV, are proposed to form a blockade of the secretion mechanism. Two mAbs that target this tip protein have gone to clinical trials, KB001-A and MED13902. KB001-A has been in phase I and II trials for VAP and chronic lung infections but did not achieve sufficient efficacy to proceed to phase III79,80. MED13902, which is a bi-specific antibody that also targets an anti-biofilm target Psl81, performed well in phase I trials82 but again did not reach efficacy levels in phase II83. Despite these setbacks, the tolerability and good pharmacokinetics/ pharmacodynamics of mAbs make them an ideal candidate for anti-virulence strategies in the future.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is the treatment of disease by the activation or suppression of the immune system. Immunotherapy has been successfully used to treat many cancers through reversal of immunosuppression. Enticingly, many bacterial infections share the same immunosuppression characteristics as cancer, suggesting that immunotherapies such as checkpoint inhibition, modulation of cytokines, or cellular therapies could be useful for fighting infection84. A case study reporting successful clearance of the fungal infection mucormycosis by a combination of nivolumab and IFN-y on a compassionate basis highlights that immunotherapy may be useful against infection85. Pre-clinical data is now beginning to emerge for various immunotherapies such as PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor treatment for P. aeruginosa and Haemophilus pylori infections or targeting IL-20 in K. pneumoniae86. However, the only use of immunotherapy in trials associated with potential Gram-negative infections is those investigating outcomes of sepsis87,88,89,90,91. These are primarily focused on safety and tolerability, with none focusing on the effect of bacterial infection. Despite the lack of clinical data, the widespread use of many immunotherapies in cancer therapy may make regulatory approval easier depending on the outcomes of clinical trials.

Conclusion

This review has highlighted emerging non-antibiotic therapies that are currently used compassionately or undergoing clinical trials to treat problematic Gram-negative infections. PT is rapidly gaining clinical validation for the targeted treatment of MDR bacteria in a diverse range of infection types. AMPs offer more broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity; however, are often more efficacious towards Gram-positive dominated infections and restricted to localized treatment due to systemic toxicity. There are multiple emerging peptides, compounds, monoclonal antibodies, as well as plasmapheresis therapy that can modulate, restore and or enhance immune responses. These therapies offer broad infection control that are less likely to induce microbial resistance, however, cases of treatment in humans are limited and lack thorough clinical validation to date.

Considering problematic MDR infections, PT is an effective antimicrobial therapy with the potential to overcome AMR, however advancements to improve the broad-spectrum activity of PT are required. Thus, PT, followed by AMPs are likely to be the next wave of antimicrobials used to treat Gram-negative bacteria. This review has also highlighted that most of these therapies will likely not replace antibiotics, and rather be used in conjunction with current standard care.

Responses