Epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical impact of bacterial heteroresistance

Introduction

Bacterial heteroresistance refers to a phenomenon where variability of antibiotic susceptibility exhibit within an isogenic clonal population1,2,3,4. Unlike homogeneous resistance, where all bacterial cells within a strain exhibit uniform resistance to an antibiotic, heteroresistance involves the coexistence of susceptible and resistant subpopulations, a small portion of the subpopulation shows resistance2. In vitro susceptibility tests reveal that most bacterial subpopulations are sensitive to the antibiotic, so the overall minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) usually remains sensitive2,5. Compared to resistance, heteroresistance is poorly understood and underappreciated6.

Heteroresistance is clinically significant, as it complicates treatment strategies by introducing subpopulations that may evade standard antimicrobial therapies7,8. What’s more, bacteria with heteroresistance to an antibiotic can more easily evolve into full resistance following clinical treatment2,9,10. Resistant subpopulations in heteroresistant strains are not killed by the antibiotic and are accumulated, eventually leading the strain to develop full resistance. Therefore, heteroresistance is considered an intermediate stage in the progression from sensitivity to resistance2,9,10. Traditional methods for testing bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics typically assess the overall susceptibility of bacterial populations, and cannot accurately determine whether bacteria exhibit heteroresistance to these antibiotics due to the frequency of the resistant subpopulation is too low to be detected from a standard inoculum11,12. The gold standard for detecting heteroresistance is population analysis profiling (PAP). This method involves inoculating bacteria on agar plates with a gradient of antibiotic concentrations and observing colony growth to identify and quantify heteroresistant strains1. This method is not widely applicable in most clinical laboratories because it is time- and labor-consuming13,14. In some respects, bacterial heteroresistance to antibiotics is more concerning than resistance itself due to its hidden nature, making it difficult to detect, and its high likelihood of progressing to full resistance.

In recent years, there has been increasing research on bacterial heteroresistance to antibiotics, particularly concerning clinically significant pathogens such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Acinetobacter baumannii et al. The heteroresistance of these pathogens to last-resort antibiotics, such as polymyxins, tigecycline, ceftazidime-avibactam, and vancomycin have garnered significant attention3,7,10,15,16,17,18,19. Since the comprehensive review on heteroresistance in 20192, to our knowledge, few equally comprehensive studies on heteroresistance have been published. To summarize the recent research findings on the heteroresistance of clinically important pathogens to critical antibiotics, this article consolidates information on their epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical impact.

Epidemiology of bacterial heteroresistance

The true prevalence of heteroresistance is uncertain: it is likely underestimated due to the lack of uniform definition and the variability of methods used to detect heteroresistance, and most studies rely on existing collections of multidrug-resistant isolates, leading to sampling bias. These all hamper comparison among studies. However, most studies published after 2019 refer to the definition and standard detection methods for heteroresistance outlined by Andersson et al.2. We presented a table summarizing data from research papers published after 2019 that utilized the PAP method for screening and followed Andersson et al.‘s definition of heteroresistance (referred to as the resistant subpopulation, typically ranging from 10−7 to 10−5) in this study (Table 1).

Overall, the prevalence of heteroresistance varies among different bacterial species and different antibiotics, and the frequency of antibiotic use also impacts the rate of heteroresistance. Heterogeneous vancomycin intermediate S. aureus (hVISA) is the only type of heteroresistance with a standardized detection assay recommended by EUCAST following the protocol described by Wootton et al.13. Since 2019, the majority of hVISA cases reported have been concentrated in Asia. The rates of heteroresistance in India, Malaysia, and Japan were 12.4, 2.19, and 5.10%, respectively20,21,22. hVISA is present at rates of 10.0% in China, showing a significantly higher isolation rate compared to global levels23. Nevertheless, the heteroresistance prevalence of vancomycin in clinical isolates of S. aureus from South Korea is 20%24. A study reported that among 40 clinical sources of S. aureus against six antibiotics, 69.2% showed heteroresistance to gentamicin, and the heteroresistance prevalence to oxacillin, daptomycin, and teicoplanin were 27, 25.6, and 15.4%, respectively. In contrast, no heteroresistance was found for linezolid and vancomycin25.

The prevalence of heteroresistance to multidrug-resistant gram-negative species is mainly reported in polymyxins (including polymyxin B and colistin), beta-lactams (including carbapenems, ceftazidime/avibactam), tigecycline and fosfomycin. These studies addressed a wide range of countries and performed different screening methods. Several studies reported that carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) exhibited a heteroresistance prevalence of ~50 to 75% to polymyxins10,26,27,28. Luo et al. emphasized that heteroresistance to polymyxin B was confirmed in the vast majority of patients (39/42,92%) before complete resistance was detected, indicating that heteroresistance may represent a transitional stage in the evolution of bacteria from sensitive to resistant10. In recent years, there has been a paucity of studies investigating colistin heteroresistance in E. coli. Two recent research studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of heteroresistance to colistin in E. coli is relatively low, with less than 5% of the population exhibiting heteroresistance26,29. It was found that 93% (15/16) of A. baumannii were heteroresistance to polymyxin and could evolve to resistance under antibiotic pressure30. Furthermore, two studies conducted in Brazil and the United States reported heteroresistance prevalence in A. baumannii of 100 and 89%, respectively31,32. However, recent studies suggest that this rate is now less than 50%29. These data are in sharp contrast with E. coli data, in which polymyxins heteroresistance seems rare (<5%).

Heteroresistance to carbapenems has also been widely studied and reported from different countries. In Spain, 18 strains of VIM-producing bacteria were examined, and it was found that 16.7% of them exhibited heteroresistance to carbapenems33. In six CRKP isolates, heteroresistance to meropenem was investigated, and it was found that all of them demonstrated positive results34. Considerable research has been conducted on the heteroresistance of E. coli to carbapenems. However, the results of these studies have been found to vary considerably. A selection of hospital isolates from Sweden, the USA, and China, was specifically chosen for investigation into the heteroresistance patterns of E. coli to imipenem, ertapenem, and meropenem15,29,35. The prevalence of heteroresistance exhibited considerable variation across these countries: Imipenem showed 0, 25, and 25% heteroresistance in Sweden, the USA, and China, respectively. Ertapenem heteroresistance prevalence were 27.3, 35, and 17.2%, and meropenem heteroresistance prevalence were 0, 30, and 3.9% for the same countries in order15,29,35. It has been reported that all eight screened A. baumannii susceptible to carbapenems exhibited colony growth within the inhibitory circle, suggesting the existence of a heteroresistance subpopulation36. However, it has also been reported that the heteroresistance prevalence of A. baumannii to imipenem and meropenem were at 20 and 0%, respectively29.

Heteroresistance to ceftazidime-avibactam was reported in China. 11.55% ceftazidime/avibactam-susceptible KPC-KP isolates exhibited ceftazidime/avibactam heteroresistance, with the primary mechanism being the presence of KPC mutant subpopulations37. Heteroresistance to tigecycline has been reported at varying rates in small epidemiological studies involving hundreds of isolates: up to 56% in A. baumannii (data from South Korea)38, 20% in E. cloacae (data from China)39, and 7.8% in K. pneumoniae (data from China)40. Fosfomycin heteroresistance is frequently observed in Enterobacterales, with prevalence estimated at ~10%5,41.

Mechanisms underlying bacterial heteroresistance

The emergence of bacterial heteroresistance is the result of the combined action of multiple genetic mechanisms, leading to phenotypic differences in resistance among different subpopulations within the bacterial community5,42,43. In-depth research on these mechanisms helps to understand the development of resistance and provides theoretical support for the clinical management of strains with heteroresistance.

Genetic mechanisms

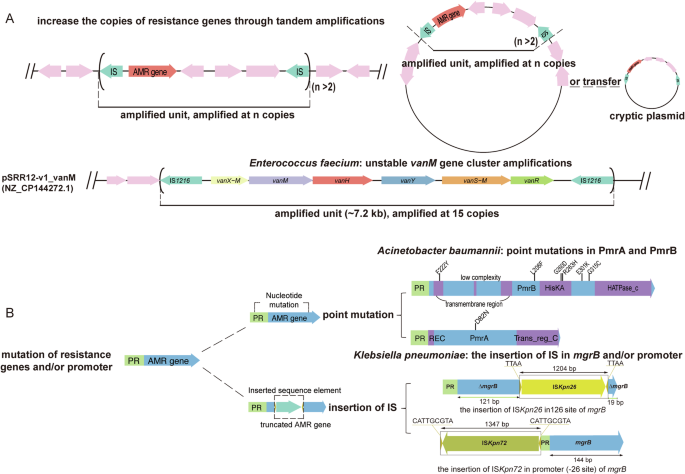

The widely recognized and accepted molecular mechanisms of heteroresistance are gene-dosage dependence and point mutations and/or mutations in genes associated with antimicrobial mechanisms2,29(Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1). Gene-dosage dependence: the copies of resistance genes or their regulators are altered through tandem amplification and/or changes in plasmid copy number, leading to an increase in resistance gene copies17,43,44,45. Tandem gene amplification often occurs in bacterial genomes, including plasmids and chromosomes, especially in regions flanked by insertion sequences, transposase genes, and ribosomal RNA operons through unequal crossing over19,29,44,46. However, these repeat sequences can lead to deletion and rearrangement via host homologous recombination19,29,44,46. Additionally, replication of amplified regions increases the risk of replication fork stalling or breakage, causing rapid gene loss43. The frequent amplification and high loss rate of these genes make such resistant subpopulations unstable and transient, leading to unstable heteroresistance in bacteria.

A Gene-dosage dependence: the number of copies of resistance genes or their regulators is altered by tandem amplification and/or changes in plasmid copy number, which leads to an increase in resistance gene copies. B Point mutations and/or mutations in genes associated with antimicrobial mechanisms. This figure was created by gggenes 0.5.1. and Adobe illustrator was performed to combine the figures.

Heteroresistance generated by tandem amplification

The tandem amplification of resistance genes is common in Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Salmonella spp., A. baumannii, and E. cloacae, and it may be the main cause of their heteroresistance29,43,44,45,47. For instance, in a combination test involving 41 Gram-negative bacteria strains and 28 antimicrobial agents (766 combinations), 27.4% exhibited heteroresistance, of which only 12% (4/34) showed stable heterogeneity, while the MIC of the remaining resistant subpopulations either completely or partially reverted to the level of sensitive subpopulations29. Research on bacterial heteroresistance to polymyxin B has indicated that an increased copy number of the pmrD gene contributes to heteroresistance in Salmonella spp44. In E. coli, IS1-mediated spontaneous and transient amplification of the arn operon increases its resistance frequency to polymyxin B by 10–100 times47. It is reported that comparative genomics of resistant and sensitive subpopulations of K. pneumoniae with heteroresistance to piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP) revealed that the resistant subpopulation had increased copy numbers of blaTEM-1, blaOXA-1, blaCTX-M-15, and blaSHV-33 due to tandem repeat regions provided by mobile genetic elements (MGEs), as well as an increase in the plasmid copy numbers45. Another study reported heteroresistance to cefiderocol in K. pneumoniae, due to an increased copy number of blaSHV-12, which manifests resistance to cefiderocol18. Furthermore, the unstable heteroresistance observed in E. coli towards the novel globomycin analog G0790, which targets the type II signal peptidase LspA, is attributed to an elevated copy number of the lspA gene, resulting in increased expression of the LspA protein48. Nicoloff et al. reported that the heteroresistance of K. pneumoniae to amikacin, tobramycin, ertapenem, tigecycline, and ceftazidime/avibactam have shown that 92% (77/83) of spontaneously mutated isolates resistant to antibiotics exhibit an increase in gene copy number, with 51% (39/77) showing gene copy number increase as the sole resistance mechanism43. Furthermore, they discovered three primary drivers of gene-dosage-dependent heteroresistance for several antibiotic classes: tandem amplification, increased plasmid copy number, and transposition of resistance genes onto cryptic plasmids43. Heteroresistance has also been reported in Gram-positive bacteria, where the tandem amplification of the vanM gene cluster on the plasmid in Enterococcus faecium leads to vancomycin HR19.

Heteroresistance generated by mutation

Point mutations and/or mutations in genes associated with antimicrobial mechanisms is another important genetic mechanism for heteroresistance. Heteroresistance occurs when point mutations occur in relevant genes associated with different subpopulations, resulting in subpopulation differences in susceptibility to specific antibiotics. These mutations can affect a variety of mechanisms, such as altered target proteins, altered mechanisms of antibiotic uptake or efflux, and enzyme-mediated antibiotic degradation3,38,49,50,51. Mutations in the genes that encode penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), including pbp1A, can reduce the antibiotic binding affinity, thereby conferring resistance to amoxicillin. A study reported that sensitive and resistant subpopulations of Helicobacter pylori with varying MICs of amoxicillin were detected in a single patient, where replacing pbp1A in the sensitive isolate with pbp1A containing two point mutations increased the MIC from 0.06 to 2 mg/L3. The inactivation, disruption, and deletion of mgrB, have been determined to be the key factors in mediating colistin resistance. In K. pneumoniae with heteroresistance to colistin, the active expression of IS903B of the IS5 family and the insertion, or even deletion of mgrB have been reported52. The upregulation of pmrA/pmrB is potentially triggered by mutations in either pmrA or pmrB, is implicated in colistin resistance via lipid A modification. It has been reported that functional domain amino acid alterations in PmrB or PmrA in subpopulations of A. baumannii heteroresistance to colistin53. The resistant subpopulation of K. pneumoniae DA76126 with heteroresistance to TZP was found to have an insertion of the promoter region of blaSHV-11 by IS1380 (ISEcp1) in comparison to the original colony genome, which may lead to the upregulation of the β-lactamase gene expression that mediates heteroresistance to TZP45. Furthermore, tigecycline resistance in subpopulations of A. baumannii might be owing to the overexpression of the AdeABC efflux pump through the insertion of ISaba1 in adeS38,54. Compared to Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria such as S. aureus have fewer resistance genes and lack direct repeat sequences, making tandem amplification of genes difficult to occur, and are mostly found to be high-frequency point mutations in core genes on chromosomes leading to heteroresistance17,25. Events such as gene and plasmid copy number increases due to tandem amplification, point mutations, and disruption of gene function due to active insertion of MGEs into the interior of genes and promoters are not singular occurrences, but can often occur in the same resistant subpopulation43.

Stability mechanisms

Evolution to resistance in bacteria could bring fitness costs, while fitness costs influence the growth rate, allotment of energy and resources, metabolism, regulation of genes, and virulence55,56,57. Tandem amplification leading to increased gene and plasmid copies is often accompanied by severe fitness costs43. The interrelated gene inserted by IS conferred the overexpression of the corresponding protein which probably made for the unstable heteroresistance38. Once the antibiotic pressure is removed, the bacteria are serially cultured in the antibiotic-free medium, and the mechanisms of unstable resistance mutations and fitness costs drive subpopulations to revert to susceptible4,58. However, resistance subpopulations caused by point mutations, which have smaller fitness costs, are relatively stable59. Additionally, the stability of bacterial heteroresistance varies due to fitness costs, the presence of IS, and antibiotic selection pressure. The higher the fitness cost, the more unstable the resulting resistant subpopulations2,43. Resistant subpopulations from stable heteroresistance have lower fitness costs (≤7%), and bacteria do not need additional compensation for growth in the absence of selective pressure29. Except for the fitness costs and the selective antibiotic pressure, the antibiotic susceptibility of subpopulations could revert by additional insertion of IS sequence and point mutation in some genes38. Research has reported that with the continuous stimulation of antibiotic selection pressure over 60 generations, stable subpopulations with low fitness costs may evolve from unstable subpopulations caused by tandem amplification46.

Theoretical models of heteroresistance

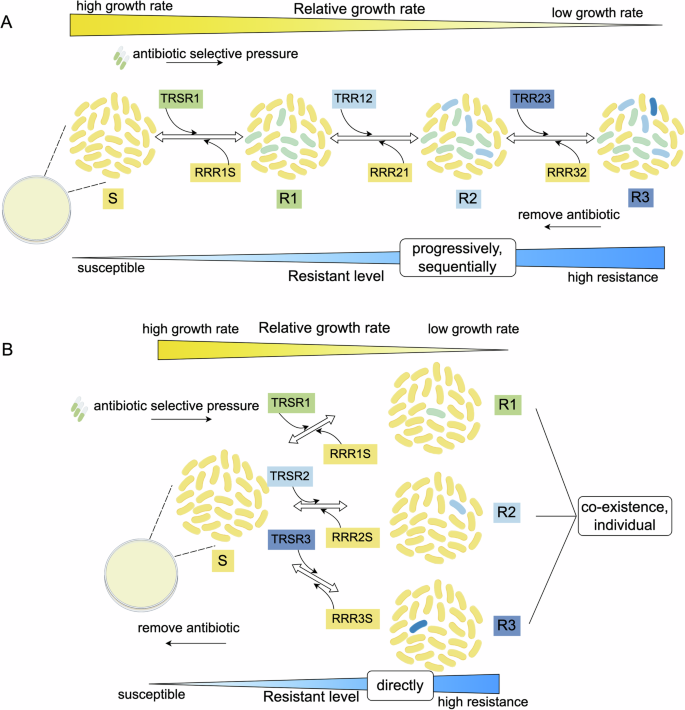

Notably, there have been breakthroughs in theoretical studies on the evolution of heteroresistance. There are two theoretical models of HR state as reported by Nicloff et al. progressive heteroresistance and non-progressive heteroresistance models4. Transitions between bacterial states in theoretical models are influenced by multiple factors such as transition rate, antibiotic concentration, growth rate of bacteria, fitness cost, environmental factors, and genetic factors. Increased levels of resistance and slowed growth rate are reflected in the model (Fig. 2).

A Progressive model of heteroresistance. In the progressive model: under antibiotic selective pressure, bacteria in the susceptible state (S) undergo sequential mutations to resistant states (R1, R2, and R3) through gene-dosage dependence mechanism and/or spontaneous mutation. It depicts a progressive escalation in antibiotic resistance and shows high MIC (minimal inhibition concentration). When the antibiotic was removed, reversion to a low resistant state follows a sequential order and reflects a stepwise loss of fitness cost. B Non-progressive model of heteroresistance in bacteria. In the non-progressive model: under antibiotic selective pressure, bacteria in the susceptible state (S) directly and stochastically transition to different resistant states (R1, R2, or R3), and the three transitions could occur simultaneously. Resistant states can revert to the susceptible state independently, indicating swift adaptive changes. TR: assumed transition rate of two contiguous states that low resistant state to high resistant state. RR: assumed reversion rate of two contiguous states from high resistant state to low resistant state. This figure was created by Figdraw (www.figdraw.com).

In the progressive model, each state of diminished susceptibility sequentially generates the subpopulation with a higher resistance level. The subpopulations that have acquired higher levels of resistance grew at a lower rate compared with the sensitive population than in the previous state and thus decreased in number successively. The subpopulation with the highest resistant level of R3 is present only in the runs with the highest transition rates (for example, values equivalent to 10−2 and 10−3 per cell per hour) (Fig. 2). It was reported that mutations progressively increase the so-called “mutation selection window”60, that is to say, the range of antibiotic concentrations within which resistant mutants are selectively amplified. How this resistance accumulates is similar to that described in the progressive model. In the non-progressive model, a susceptible population directly generates populations with different resistance levels. When confronted with antibiotics, a non-progressive heteroresistant population will respond to the antibiotics more consistently and rapidly than a progressive heteroresistant population (Fig. 2). These two models are theoretical and need further experiments to demonstrate.

Clinical implications and impact

The emergence of bacteria heteroresistance has made clinical treatment challenging. Patients may face reduced treatment efficacy, adverse reactions, and limited options for effective antimicrobial therapy, leading to potential worsening of clinical outcomes and increased risk of mortality. However, the conclusion that heteroresistance has a negative impact on anti-infective treatment remains controversial2,5,6,7,35,50,61,62. We must emphasize that patients infected with these heteroresistance bacteria in hospitals often have underlying conditions and compromised immune systems, which inherently negatively impact treatment outcomes. Therefore, whether heteroresistance directly affects patient treatment outcomes requires extensive case studies and rigorous controlled research.

Some studies reported that heteroresistance bacteria will worsen clinical treatment outcomes. For example, a 41-year-old male patient infected with hVISA experienced recurrent episodes and, despite long-term treatment, the infection showed resistance to medication, leading to treatment failure63. The hVISA strain was also isolated in a patient with persistent bacteremia in Argentina who developed a fatal case of infective endocarditis with brain abscess seven days after receiving vancomycin treatment64. In a clinical case of treatment failure involving heteroresistance A. baumannii in Iran, the A. baumannii strain exhibited heteroresistance to colistin and eventually progressed to complete resistance during the course of treatment65. Studies also have found no correlation between heteroresistance and clinical treatment failure. It has been shown that the results of hVISA bacteremia are similar to those of fully sensitive isolates, suggesting that the hVISA phenotype is not associated with clinical outcomes66,67. In our previous study, we explored the clinical relevance of heteroresistance to polymyxin B in CRKP. We discovered that a significant proportion of previously undetected polymyxins heteroresistance were present prior to exposure to polymyxin B. Furthermore, a substantial portion of these PHR strains evolved into fully resistance following treatment with polymyxin B10.

The mice infection model was employed to investigate whether heteroresistance has an impact on clinical treatment outcomes. In the United States, a case reported that colistin heteroresistance CRKP demonstrated active growth of subpopulations even at high antibiotic concentrations of up to 100 µg/mL, ultimately resulting in treatment failure in a mouse mode68. Studies conducted by Band et al. revealed that colistin heteroresistant E. coli exhibited an increased frequency of resistant subpopulations in mice due to innate immune defenses when exposed to colistin-free conditions, leading to subsequent treatment failure with colistin69. Furthermore, studies have indicated that over time, heteroresistance to glycopeptides in S. aureus increases in the absence of antibiotic treatment70. Meanwhile, a hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae isolates evaluated by an in vivo murine infection model was found to be highly virulent and heteroresistance to colistin71. In addition, a rabbit endocarditis model has also been used to demonstrate the association between treatment failure with vancomycin and two hVISA isolates72. A series of animal studies have shown that the presence of small resistant subpopulations (10−2–10−6) often leads to treatment failure2.

Heteroresistance carries the risk of evolving into resistance, which is a significant factor affecting treatment efficacy, and thus indirectly impacts the effectiveness of treatment. As reported in our previous study, heteroresistant strains were found to exist prior to antibiotic exposure, and a significant portion of them evolved into complete resistance after receiving corresponding antibiotic treatment, which may lead to clinical treatment failure10. Using combination therapy with antibiotics seems to be a more suitable strategy than monotherapy to prevent the occurrence and evolution of resistant subpopulations to full resistance9,28,73,74. The risk of treatment failure in heteroresistance is probabilistic, just as in stable resistance, and is influenced by other factors such as the host immune system, differences in the site of infection, chronic infection course, the total density of infecting bacteria, and local antibiotic concentrations.

Conclusions and future prospects

The development of faster, more sensitive and accurate diagnostic methods is urgently needed. The combination of microscopy and microfluidic techniques allows the detection of heteroresistance by determining the individual growth rates of millions of single cells, such as the employment of single-cell sequencing and Raman spectroscopy techniques75,76. However, these methods still have a long way to go before they can be truly applied in clinical settings.

Only with a clear understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying heteroresistance can we devise strategies to overcome them. Future research is needed to elucidate the molecular basis of heteroresistance communication and its role in resistance spreading. This knowledge will enable the development of effective inhibitors targeting key pathways, potentially leading to reducing therapeutic failures. Currently, although more and more researchers are focusing on heteroresistance, it remains an emerging field that requires further clarification.

Responses