A historical perspective on the multifunctional outer membrane channel protein TolC in Escherichia coli

Introduction

TolC is a versatile outer membrane channel in Escherichia coli named for its role in providing “tolerance” to colicin E1—a pore-forming E. coli toxin1. Colicin-tolerant (tol) mutants of E. coli were first reported in 19642. By 1967, three classes—tol II, tol III, and tol VIII—were identified, with tol VIII mutants exhibiting tolerance specifically to colicin E1 while still adsorbing the molecule on the cell surface1. At this point, it was noted that the tol VIII mutants were sensitized to various antimicrobial agents, dyes, and detergents, which was attributed to increased uptake due to alterations in permeability1. The mutations associated with the tol VIII phenotype were mapped to a region between str and his1, and this location was later denoted the tolC locus in 19713. The product of tolC was identified as a 54 kDa protein in 19824, and in the following year, it was determined that TolC is synthesized with an N-terminal signal sequence that is post-translationally cleaved to yield a 52 kDa protein5. The nucleotide and amino acid sequences of tolC were determined in 19836, and shortly after, TolC was identified as an outer membrane protein7. During this time, it was acknowledged that tolC mutations were also associated with alterations in bacteriophage sensitivity8 and reductions in the outer membrane protein OmpF9,10. Thus, tolC gained a reputation for its importance in E. coli outer membrane structure and function, in addition to antimicrobial resistance, and it was noted that the tolC mutant phenotype was pleiotropic in nature.

In the 1990s, TolC was found to have multiple roles, including the secretion of hemolysin11, colicin V12, STB enterotoxin13, and the antibacterial peptide microcin J2514. Conversely, during this time, TolC was also shown to be essential for the uptake of colicin E115. It wasn’t until nearly 30 years after the identification of tolC that the product of this gene was hypothesized to be a component of the AcrAB efflux machinery and likely other efflux systems in E. coli, explaining why tolC mutants are hypersensitive to a broad spectrum of antimicrobial agents16 and why TolC is essential for the multiple-antibiotic-resistance (Mar) phenotype16,17.

The first high-resolution crystal structure of TolC was reported in 2000, revealing a fold distinct from other outer membrane proteins in E. coli18. Three TolC protomers were demonstrated to assemble, forming a 140 Å-long ‘channel tunnel’ spanning the outer membrane and the periplasm, with the proximal end being sealed with coiled helices, suggesting that protein-protein interactions open the channel18. It was recognized that ‘outer membrane factors’ such as TolC enable transport across the two membranes of Gram-negative bacteria, a process that also requires a cytoplasmic membrane export system or translocase/efflux pump, providing substrate specificity and energy, coupled with a membrane fusion protein18,19,20. In 2004, the AcrAB efflux pump and fusion protein were shown to form a strong interaction with TolC21. This finding was further substantiated in 2014 when electron cryo-microscopy (cryo-EM) revealed the AcrAB-TolC structure22 and in situ structures were determined by electron cryo-tomography23,24, solidifying the role of TolC in antimicrobial drug efflux. Concurrently, it was increasingly recognized that TolC likely exports endogenously produced substrates such as the siderophore enterobactin25, indole26, and porphyrins27, underscoring its broader role in cellular homeostasis and metabolism. Thus, TolC has been associated with a multitude of cellular functions in E. coli, highlighting its versatility and importance in bacterial physiology.

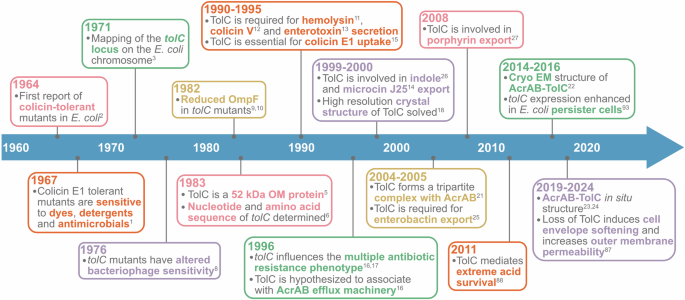

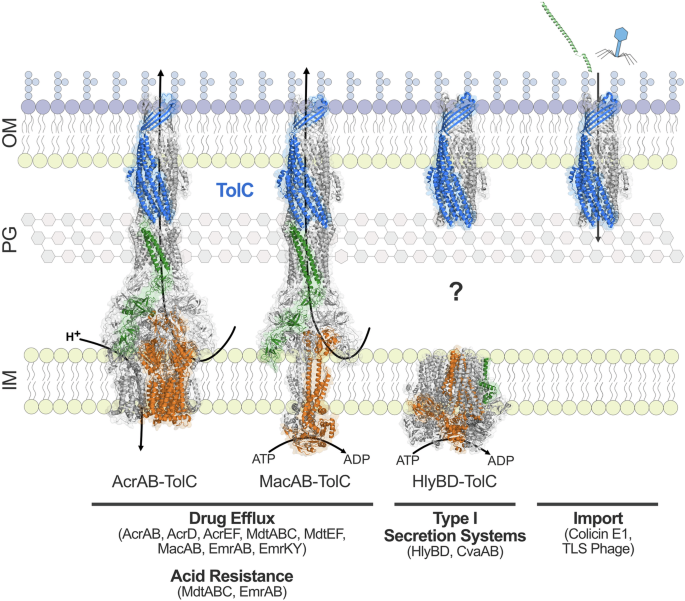

This review commemorates the 60th anniversary of the discovery of colicin-tolerant E. coli mutants—and the identification of TolC—by presenting key discoveries that highlight its multifunctional role in antimicrobial resistance, metabolism, membrane integrity, and host survival (summarized in Fig. 1). While previous reviews have offered excellent insights into the structure and function of TolC28,29, we provide updates from the past decade and highlight areas that remain incompletely understood. Although TolC has been the primary focus of research over the years due to its well-established role in multidrug efflux and other important processes, the E. coli genome encodes several other homologous outer membrane channel proteins that remain poorly characterized. Here, we demonstrate that these homologous proteins are highly conserved across the E. coli species, suggesting their potential importance in cellular physiology or stress responses.

Significant discoveries in TolC research that underscore the multifunctional role of this outer membrane protein.

Structure and assembly of TolC

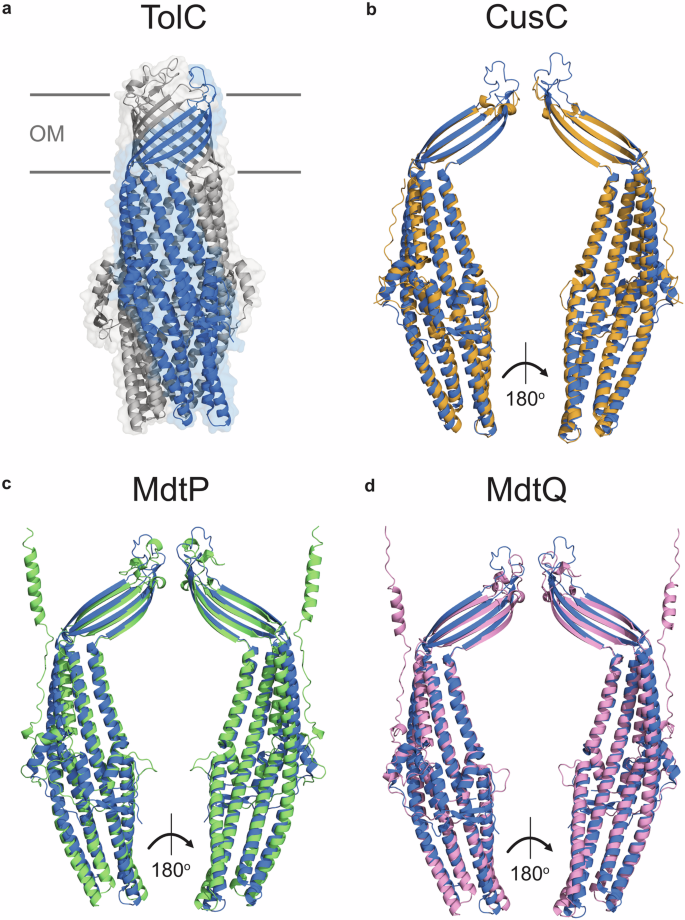

Nearly 25 years ago, the αβ-barrel structure of TolC was determined, showing that this protein forms an extended homotrimer projecting into the periplasm (Fig. 2a)18. This architecture is structurally unique among E. coli outer membrane proteins (OMPs), which are generally oligomeric, with each monomer forming an individual β-barrel monomer18. The upper portion of TolC is a 12-stranded β-barrel formed by four β-strands from each protomer18. The β-barrel of trimeric autotransporters in E. coli are assembled in a similar manner30, but this class of proteins lacks the unusual α-helical barrel composed of two long and four short α-helices from each TolC promoter that extends from the β-barrel into the periplasm18. Most OMPs form multimeric channel complexes, yet TolC forms a single cone-shaped channel with a large internal cavity volume of ~43,000 Å3 18. An internal diameter of ~20 Å is maintained for roughly ~100 Å of the protein18,31, and the radius reduces to ~2 Å towards the periplasmic end of the protein where the α-helices wind around each other to form a coiled-coil that seals the channel18,32. The closed periplasmic end of TolC is maintained by strong inter-protomer salt bridge interactions and intra-monomer hydrogen bonds33.

a Ribbon diagram of TolC (PDB code: 1EK9). TolC is assembled from three protomers; chain A is coloured blue, and chains B and C are coloured grey. b Ribbon diagram of the CusC protomer (PDB code: 4K7R, shown in orange) superimposed on chain A of TolC (PDB code: 1EK9, shown in blue). Z-score of the protein pair: 28.1, root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the alpha carbon atoms: 2.1 Å, amino acid sequence identity: 17%. c Ribbon diagram of the MdtP protomer (AlphaFold code: AF-P32714-F1-v4, shown in green) superimposed on chain A of TolC (PDB code: 1EK9, shown in blue). Z-score of the protein pair: 24.8, RMSD of the alpha carbon atoms: 3.4 Å, amino acid sequence identity: 15%. d Ribbon diagram of the MdtQ protomer (AlphaFold Code: AF-Q8X659-F1-v4, shown in pink) superimposed on TolC (PDB code: 1EK9, shown in blue). Z-score of the protein pair: 26.0, RMSD of the alpha carbon atoms: 3.4 Å, amino acid sequence identity: 12%. Structure superpositions and Z-scores were generated using DALI Pairwise structure comparison and visualization using PyMOL. Z-scores ascribe statistical significance to the similarity between two protein structures, with scores over 20 indicating the structures are homologous. OM outer membrane.

While the structure of TolC is well-characterized, how the protein folds and is assembled in the outer membrane needs to be better understood. Nearly all OMPs adopt topologically homogeneous β-barrel structures34, and while their folding mechanisms are not fully understood, the translocation and assembly module (TAM) and the β-barrel assembly machinery (BAM) complex (BamABCDE) function synergistically for OMP assembly in the outer membrane35,36,37,38. The biogenesis of TolC is similar to that of other OMPs; it is synthesized in the cytoplasm with an N-terminal signal peptide that facilitates the translocation of unfolded TolC into the periplasm through the Sec translocon39,40. Most OMPs remain unfolded in the periplasm and require periplasmic chaperones to traverse the periplasm before interacting with the BAM complex for assembly and insertion into the outer membrane41. Evolutionary studies indicate that TolC is unrelated to other β-barrel OMPs, having evolved from periplasmic efflux pump adaptor proteins and convergence on the β-barrel fold34. However, others have demonstrated that outer membrane β-barrels in Gram-negative bacteria—including TolC—share a common origin and evolved from a single, ancestral ββ hairpin42.

Despite this, TolC is structurally distinct from other proteins assembled by the BAM complex or the TAM and appears to follow a unique assembly pathway that does not rely on known chaperones43. TolC folding involves two intermediates, where the primarily α-helical TolC monomer first folds, and then the trimer assembles in the periplasm before being inserted into the outer membrane40. The TAM complex organizes and inserts the TolC β-barrel into the outer membrane44. The role of the BAM complex is less well understood. While this protein complex is associated with TolC biogenesis45, the mechanism proceeds independently of the BamA periplasmic polypeptide transport-associated (POTRA) 1 domain involved in assembling most OMPs41. Several TolC homologs in other bacterial species, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa OprM, are lipoproteins46 transported to the outer membrane with assistance from the Lol machinery47. The E. coli LolCDE is interchangeable with the P. aeruginosa LolCDE complex and can transport OprM to the outer membrane47; however, TolC lacks the characteristics of lipoproteins, including lipidation.

While the precise mechanism of TolC biogenesis is not fully understood, the data suggests that the α-helical barrel likely assembles within the periplasm, avoiding the need for chaperone assistance to traverse this region40. The transmembrane domain of TolC is then assembled and inserted into the outer membrane by the TAM and BAM complexes through a poorly understood mechanism38,44.

While recent studies have provided more profound insight into the TolC biogenesis and assembly pathway, future research should elucidate the detailed molecular mechanisms, including the specific interactions and sequence of events involved in the assembly of its α-helical barrel and transmembrane domain, as well as any potential accessory factors that may contribute to its efficient integration and folding.

Other outer membrane channel proteins in E. coli

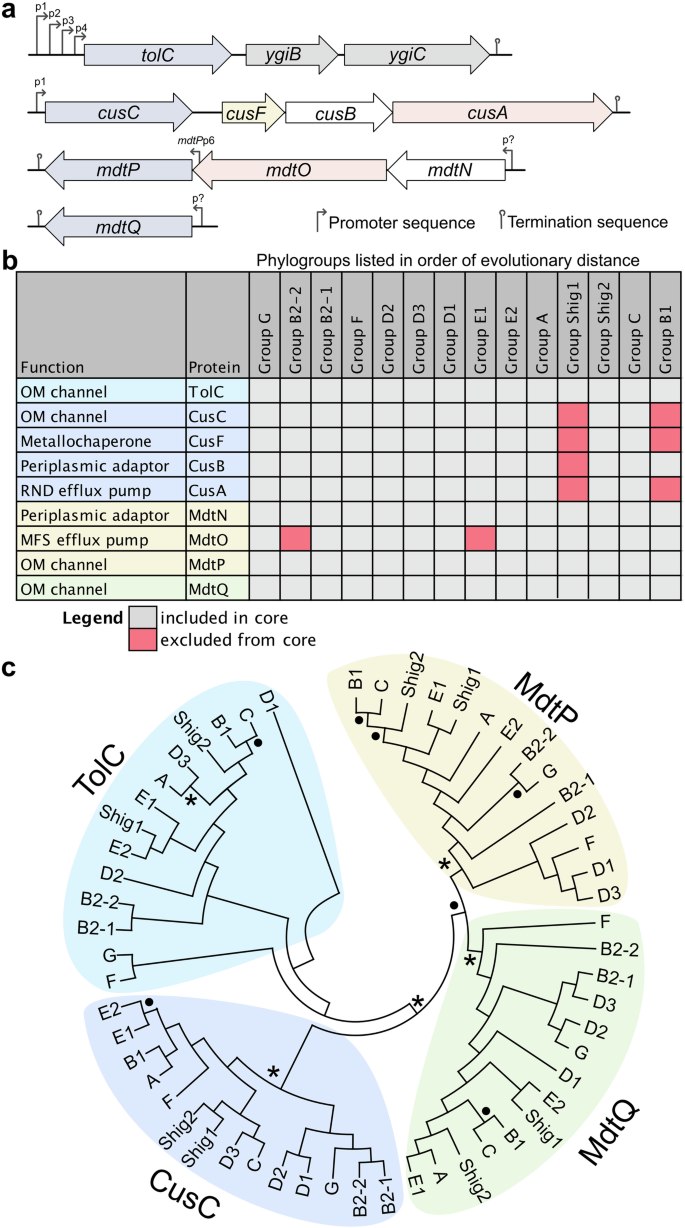

Although TolC has been extensively studied, E. coli encodes three additional less well-studied homologous outer membrane channel proteins, also known as outer membrane factors: CusC (formerly YlcB), MdtP (formerly YjcP), and MdtQ (formerly YohG) (Fig. 2)48. The cusC and mdtP genes are encoded within operons, whereas mdtQ is encoded independently (Fig. 3a). The cusC and mdtP operons also contain genes encoding proteins that either assemble or are likely to assemble with these outer membrane channels (Fig. 3a). cusC is part of the CusCFAB cation efflux system, which plays a critical role in the extrusion of copper and silver ions49,50. The function of MdtP and MdtQ have not been elucidated; however, mdtP is encoded in an operon with a putative periplasmic adaptor protein (MdtN) and an inner membrane major facilitator superfamily efflux pump (MdtO)51. Null mutants of mdtP and mdtQ in E. coli display increased susceptibility to puromycin, acriflavine, and tetraphenylarsonium chloride, indicating they may be involved in transport48. Intriguingly, tolC is expressed in an operon with two genes of unknown function52: ygiB and ygiC (Fig. 3a). While YgiB is predicted to be an OM lipoprotein52, the AlphaFold predicted structure (AF-P0ADT2-F1-v4) displays low confidence, and the function of this protein remains unknown. YgiC is homologous with the C-terminal domain of E. coli GspS, which exhibits glutathionylspermidine (GSP) synthetase and GSP amidase activities52. Based on sequence similarity with GspS, it is predicted that YgiC is a GSP synthetase, yet the enzyme lacks this activity53. YgiC has since been shown to possess peptide-spermidine ligase activity, associating the enzyme with polyamine metabolism, yet the physiological substrate remains unknown54. Deleting these genes does not affect the localization, folding, or activity of TolC52; however, they are associated with the severe growth defects exhibited by tolC mutants in minimum medium with glucose supplied as the carbon source52.

a Schematic representation of operons harbouring outer membrane channel protein-encoding genes (blue). Efflux pump-encoding genes are colored red, periplasmic adaptor proteins are white, and chaperons are yellow. Predicted promoters are labelled. The promoters controlling expression of the mdtNOP operon and mdtQ have not been experimentally confirmed. A second promoter is thought to control mdtP expression, which requires experimental validation. b Heat map demonstrating the conservation of outer membrane channels and their cognate efflux pumps within the core genome. Phylogroups are listed in order of increasing distance from the common ancestor. Notable phylogroup sources include poultry/bird fecal isolates (G/F), nonhuman mammalian isolates (D2), human UPEC isolates (D1/D3), commensal laboratory strains (A), and aquatic isolates (B1). A lowered cutoff threshold (E < 1.0e-10) identified homologs of mdtO in the B2-2 and E1 core genomes. Core genome data were provided by Abram et al. for the 14 phylogroups, which were searched using BLASTP (cutoff threshold E < 1.0e − 50) to assess the conservation of each outer membrane channel (n = 4) and the corresponding tripartite efflux systems. c The phylogenetic relationship of the outer membrane channels was assessed using circular cladograms of the 14 medoid strains determined by Abram et al. The medoid genome assemblies were acquired from NCBI, and the nucleotide sequences for the corresponding efflux pumps were extracted in Geneious and exported in FASTA format. FASTA files were aligned in MEGA X, and unrooted maximum-likelihood trees were generated using a rapid bootstrap analysis of 100 replicates. Asterisks represent bootstrap values of 100, and black circles represent bootstrap values of 80 to 99. Abbreviations: OM, outer membrane; RND, resistance-nodulation-cell division; MFS, major facilitator superfamily.

While the CusC, MdtP, and MdtQ channel proteins exhibit low (<20%, Fig. 2) amino acid sequence similarity to TolC, their known or predicted structures are homologous to TolC, as determined using the distance matrix alignment (DALI) pairwise structure comparison server (Fig. 2)55,56. The structure of CusC has been determined57, and superposition with TolC demonstrates that the proteins are highly similar, with an alpha-carbon position root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 2.1 Å (Fig. 2b). The structures of MdtP and MdtQ have not yet been determined, yet the superposition of their predicted structures with that of TolC reveals that they are similar to TolC (Fig. 2c, d), which requires experimental validation.

Given the poorly understood functions of TolC homologs in E. coli, we assessed the conservation of these outer membrane factors and their associated efflux systems within the core genome of E. coli (Fig. 3b). There are 14 distinct E. coli phylogroups, each exhibiting unique patterns of gene conservation58. Similar to our previous analysis of E. coli efflux pump-encoding gene conservation59, we performed BLASTP searches against the core genome of each phylogroup58, revealing that the outer membrane channel proteins are highly conserved while the conservation of their cognate efflux systems is more variable (Fig. 3). mdtQ is conserved in the core genome of E. coli despite its annotation as a pseudogene60. The conservation of these efflux-associated outer membrane channels indicates they have been maintained throughout evolution despite the genetic diversity of E. coli. The phylogenetic relationship of these outer membrane channels was also assessed using unrooted maximum likelihood trees of medoid strains (i.e., a representative strain that is the genetic center of each phylogroup) (Fig. 3c), as defined by Abram et al.58. This analysis demonstrates that TolC is most similar to the CusC cation outer membrane channel61 and that MdtQ and MdtP are divergent and may have distinct functions.

Future research should investigate the roles of these poorly characterized outer membrane channels to understand their contributions to bacterial physiology and adaptation, focusing on environmental stress resistance, antimicrobial efflux, and virulence. Additionally, the physiological roles of YgiB and YgiC should be explored, which are encoded alongside tolC in the same operon, with particular attention to their involvement in TolC-associated pathways and polyamine metabolism and their significance in E. coli physiology.

The regulation of tolC expression

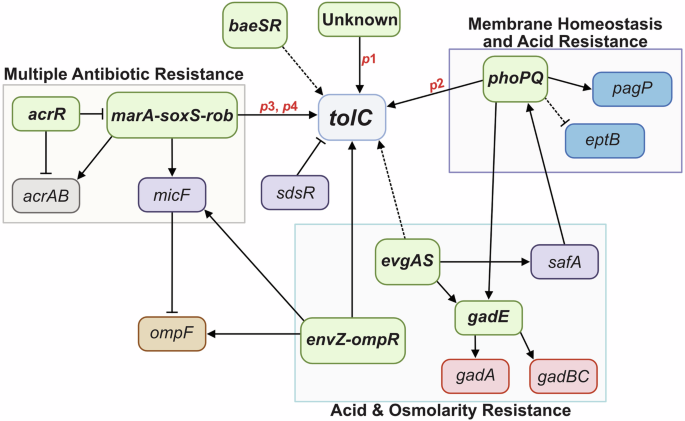

Each E. coli cell is estimated to contain approximately 1500 copies of the TolC protein21, with these numbers increasing in response to environmental stimuli. The tolC expression regulatory network is complex, with the identification of four tolC promoters (p1, p2, p3, and p4) (Fig. 4)62. Similar to the genes encoding the AcrAB efflux system, tolC is a member of the marA, soxS, and rob (marA/soxS/rob) transcriptional regulon, which is upregulated in response to environmental stressors such as superoxide stress, heavy metals, bile salts, and antibiotics63,64. MarA, SoxS, and Rob bind to a 19 bp DNA sequence called the marbox, located in the promoters of target genes65. The majority of MarA residues that interact with the marbox are conserved in SoxS and Rob as well, enabling these regulators to activate a similar set of target genes66,67. This includes tolC, where the marbox is positioned between the p2 and p3 promoters68. When MarA, SoxS, or Rob bind to this marbox, they activate tolC expression from the p3 and p4 promoters64,68.

Promoters are shown in red, two-component systems/transcriptional regulators in green, efflux pumps in grey, porins in brown, outer membrane asymmetry factors in blue, acid resistance factors in pink, and other factors of the regulatory network in purple. Boxes group together two-component systems/transcription regulators that share physiological functions with TolC and are activated by similar environmental stimuli. Solid lines represent direct regulation, and dashed lines represent indirect regulation. Arrows represent activation, and bars represent repression.

The p1 and p2 promoters are located upstream of the marbox and are controlled by other transcriptional regulons. The regulation of p1 remains unknown, and p2 is regulated by the two-component systems PhoPQ and EvgAS69. PhoPQ is activated under low levels of divalent cations such as Mg2+ 70, activating genes associated with cell envelope stress, including divalent cation homeostasis, acid resistance (e.g., gadE71), antimicrobial peptide resistance, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) modification (e.g., pagP and eptB72,73). EvgAS regulates the expression of genes involved in acid resistance, including gadE74, and indirectly controls tolC expression by activating PhoPQ via the regulatory protein SafA, which increases PhoP phosphorylation75. PhoP binds upstream of tolC p1, increasing expression69,76. Other less well-understood two-component systems linked to tolC expression include EnvZ-OmpR, which is implicated in upregulating tolC in response to high environmental osmolarity77,78 and BaeSR, which indirectly enhances tolC expression79.

Since TolC is involved in the uptake of colicin E1 and is also a cell surface receptor for certain bacteriophages, there are several instances where the downregulation of tolC expression could be beneficial. At present, no direct transcriptional repressors of tolC have been reported; however, AcrR—the acriflavine resistance regulator—is a global repressor of the marA/soxS/rob regulon, and thus indirectly represses tolC80, in addition to directly repressing the acrAB efflux pump-encoding genes81. Additionally, the small regulatory RNA (sRNA) SdsR, or RyeB, abundantly expressed during the stationary phase, is a post-transcriptional repressor of tolC82.

In summary, tolC expression is governed by a complex network of regulators, with some acting directly on one of the four tolC promoters and others acting indirectly. Figure 4 provides a schematic overview of our current understanding of tolC regulation. Although an OmpR binding site is upstream of p177, the specific regulators controlling expression from this promoter remain unidentified, highlighting that undiscovered factors or conditions may modulate activity. Future research should explore environmental cues that trigger p1 activation, providing a more comprehensive view of the regulatory landscape of tolC.

The diverse functions of TolC

The complex regulatory network governing tolC expression reflects the multifunctional nature of this outer membrane channel, enabling adaptation and survival of E. coli in different environmental conditions. TolC is implicated in a wide range of physiological functions, which we expand upon below, and the inactivation of tolC is associated with pleiotropic phenotypes. It is well established that TolC is a fundamental component of the efflux machinery and is thus an essential antimicrobial resistance factor (Fig. 5)16,83. The protein is also a component of type I secretion systems11, enabling delivery of virulence factors, functions as a receptor for bacteriophage TLS84, and is exploited for entry of the colicin E1 toxin85,86 (Fig. 5). However, several tolC mutant phenotypes remain poorly understood, such as decreased membrane integrity9,10,87, altered cell envelope mechanics87, and reduced acid survival88. Insights from analyzing tolC regulatory pathways suggest that some of these phenotypes may result from the activation of two-component systems and transcriptional regulators, and thus their target genes, in response to the inactivation of tolC (Fig. 4).

TolC (blue) forms a tripartite complex with eight drug efflux pumps to mediate antimicrobial resistance and two drug efflux pumps to mediate acid resistance in E. coli. The structures of AcrAB-TolC (PDB code: 5V5S) and MacAB-TolC (PDB code: 5NIL) have been determined. TolC (PDB code: 6WXH) also complexes with type I secretion systems in E. coli, including HlyBD (PDB code: 8DCK). The question mark signifies the unresolved mechanism by which TolC assembles with HlyBD in the periplasm, as the structure of this complex remains undetermined. TolC is also exploited by colicin E1 (shown in green, PDB code: 6WXH) and TLS bacteriophage for entry into the cell. Inner membrane pumps are shown in orange, periplasmic adaptor proteins are shown in green, and the outer membrane channel TolC is shown in blue. Transport is driven by either the proton motive force or ATP hydrolysis. Abbreviations: OM, outer membrane; PG, peptidoglycan; IM, inner membrane.

Antimicrobial resistance

Arguably, the most prominent role of this outer membrane channel protein is intrinsic antimicrobial resistance through the formation of tripartite complexes with resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND), ATP-binding cassette (ABC), and major facilitator superfamily (MFS) efflux pumps in E. coli89 (Fig. 5). These multicomponent complexes collectively provide broad-spectrum resistance to antimicrobial agents83,90. Additionally, as a component of the efflux machinery, TolC indirectly facilitates the acquisition of horizontally acquired resistance mechanisms in the presence of growth inhibitors, which may play a role in the dissemination of drug resistance91 and contributes to persister cell formation in E. coli in the presence of antimicrobial agents92.

TolC is considered non-selective, with antimicrobial substrate specificity originating from the efflux pumps and their periplasmic adaptor proteins93,94. However, the internal surface of the periplasmic end of TolC’s α-helical barrel is electronegative, which may hinder the transport of specific substrates through the channel18, and several residues in the α-helical barrel are associated with substrate specificity93. TolC forms cell envelope-spanning complexes with at least eight different efflux pumps and their corresponding periplasmic adaptor proteins in E. coli: AcrAB, AcrAD, AcrEF, MdtABC, MdtEF, MacAB, EmrAB, and EmrKY88 (Fig. 5). Structures of TolC in complex with AcrAB22,23,24, MacAB95, and EmrAB96 have provided valuable insights into its association with these pumps, but without corresponding structures for the remaining complexes, the molecular mechanisms of TolC’s interactions with a broader array of pumps remain speculative. This gap underscores the need for further structural studies to clarify how TolC facilitates multidrug resistance across diverse efflux systems.

TolC adopts an open conformation to facilitate the efflux of substrates across the outer membrane; when the protein is not in a complex with inner membrane components, the closed periplasmic end of TolC impedes small molecules from entering its channel and thus must be opened for transport33. The in situ structure of AcrAB-TolC reveals that the peptidoglycan layer interfaces between AcrA and TolC24. The β-barrel opening of TolC at the outer leaflet of the outer membrane is more than 10 Å wide, facilitating the easy passage of substrates24. The AcrA periplasmic adaptor protein, anchored to the inner membrane, makes extensive contact with the AcrB efflux pump and contacts the peptidoglycan and TolC, communicating AcrB conformational changes to the outer membrane channel24. To open TolC, conformational changes in AcrB, induced by drug binding, are relayed to TolC through the interface of TolC and AcrA, which leads to the twisting of AcrA and the opening of the channel24. The small protein AcrZ also interacts with AcrB in the inner membrane influencing substrate specificity97.

The factors driving the assembly of these tripartite complexes are intricate and still need to be fully understood. TolC exhibits differing affinities for the periplasmic adaptor proteins, which are dynamic interactions impacted by oligomerization and pH98. Given that TolC can assemble membrane-spanning complexes with a variety of structurally distinct inner membrane efflux pumps, their periplasmic adaptor proteins, and type I secretion systems, future research should examine the environmental signals and mechanisms driving the recruitment and formation of these multi-component complexes. This investigation may reveal whether these assemblies have unifying structural or functional features or if TolC exhibits flexibility in its interactions with different inner membrane components.

TolC-mediated export of endogenously produced physiological substrates

In addition to exporting exogenous antimicrobial compounds as a defense strategy, TolC also facilitates the extrusion of several endogenously produced compounds, including virulence factors, as described in the section below. During microbial competition, TolC facilitates the efflux of antimicrobial peptides such as colicin V12 and microcin J2514. TolC associates with the ABC transporter CvaAB to export colicin V12,99 and the ABC transporter YojHI to export microcin J25100. TolC is also involved in the export of metabolites in conjunction with inner membrane drug efflux pumps59. We have demonstrated that the E. coli drug efflux network is highly conserved in E. coli, indicating that these proteins contribute to important physiological functions59. Perhaps the most well-known example is enterobactin, a high-affinity siderophore synthesized and secreted by E. coli for environmental iron acquisition101. The large size of enterobactin restricts it from diffusing through porins, indicating that a transporter is required for transport across the outer membrane25. The inactivation of tolC impairs E. coli growth under iron-limiting conditions25, which is attributed to the periplasmic accumulation of enterobactin that TolC ordinarily exports with assistance from inner membrane efflux pumps101,102. TolC is also linked to the export of several other metabolites, including porphyrins27 and reactive nitrogen species103. Untargeted metabolomics supports a role for TolC in central metabolism104,105, and future studies should experimentally validate the export of identified metabolites. Further details pertaining to the drug efflux pump-mediated export of metabolites can be found in our review article on the physiological roles and conservation of E. coli drug efflux pumps59.

TolC and cell envelope integrity

TolC has long been associated with cell envelope integrity and function in E. coli. Early studies demonstrated that tolC mutants exhibit reduced levels of the outer membrane protein OmpF9,10, which is now known to be due to upregulation of the mar-sox-rob regulon, and particularly Rob, the primary regulator involved in increased MicF expression in tolC mutants106. MicF is a small regulatory RNA that binds upstream of ompF mRNAs, inhibiting translation106. Since several antibiotics enter the cell through porins such as OmpF (reviewed in107), the cell may respond to loss-of-efflux by reducing the uptake of toxic compounds. Another early observation was that tolC mutants exhibited heightened sensitivity to various antimicrobial agents, initially attributed to increased outer membrane permeability1. Although it is now understood that the primary role of TolC in antimicrobial resistance involves its participation in drug efflux systems, inactivating tolC leads to pleiotropic effects on the cell beyond drug efflux alone. While we acknowledge that several phenotypes, particularly growth defects, are evident in an iron-limited minimal medium, we have demonstrated that the inactivation of tolC induces cell surface structural changes and a reduction in cell envelope mechanics under nutrient-rich conditions87. A decrease in cell envelope mechanical strength and surface morphological changes indicate outer membrane defects in tolC deficient strains since this structure is the major contributor to E. coli stiffness and strength108. Supporting defects in outer membrane composition, we also demonstrated that the inactivation of tolC sensitized E. coli to perturbations in LPS transport, and we identified a synthetic sick interaction between tolC and msbA, the gene encoding the translocase essential for transporting LPS across the inner membrane87. Synthetic sick interactions occur when the combination of two genetic or chemical perturbations leads to greater fitness defects than either perturbation alone109. These interactions highlight the intricate relationships between genes and can provide insights into cellular pathways and mechanisms.

We hypothesize that tolC mutants exhibit changes in the lipid composition of the cell envelope, including alterations to the LPS structure, as well as potential disruptions to the asymmetric organization of the outer membrane. Indeed, tolC mutants are resistant to the LPS-specific phage U3110, and there are anecdotal references to alterations in the properties of LPS in tolC mutants111. For example, tolC mutants exhibit many of the characteristics of ‘deep-rough mutants’ associated with changes to the core oligosaccharide region of LPS111. The LPS core, particularly the heptose (Hep) core region, is critical for outer membrane stability112, with the phosphoryl moieties enabling divalent cross-linking of adjacent LPS molecules113. TolC was proposed to play a role in the maturation-assembly of LPS by converting the inner core HepI pyrophosphorylethanolamine (2-aminoethanol; PPEtN, or PPEA) to phosphate after the export of LPS111. Blockage of the HepI-phosphate in a tolC mutant could explain the decreases in membrane integrity and cell envelope mechanics87 since the HepI phosphate contributes to membrane stability112. However, the data supporting a role for TolC in the conversion of HepI-PPEtN remains unavailable, with existing references relying on unpublished data111. Additionally, MacA, the periplasmic adaptor protein of the MacAB-TolC efflux pump, binds rough LPS with high affinity; however, it has not been demonstrated that LPS is transported by this efflux assembly114.

In summary, while several lines of evidence link TolC to cell envelope integrity and LPS in E. coli, much remains to be understood about the precise mechanisms underlying these associations. We note that tolC regulators also control genes associated with outer membrane symmetry, and we hypothesize that some of the phenotypes may be regulatory in response to the loss of tolC (Fig. 4).

Virulence, pathogenicity, and host interactions

A unifying feature of TolC’s diverse functions is its critical role in host survival. This multi-functional outer membrane protein is essential for the efflux of antimicrobial compounds used to treat infections and for enabling bacterial cells to adapt to hostile environments within the host. As a critical component of the type I secretion system (T1SS) (Fig. 5), TolC enables the secretion of virulence factors that enhance the ability of pathogenic E. coli strains to colonize, invade, and persist within host tissues. Hemolytic E. coli activity was first described in 1960, which was later attributed to the cytolytic α-hemolysin (HlyA) T1SS comprised of HlyB, HlyD, and TolC (reviewed in115). Akin to the tripartite drug efflux machinery, this secretion system spans the entire cell envelope and features an inner membrane ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter (HlyB), periplasmic adaptor protein (HlyD), and outer membrane factor (TolC). To date, the structure of an assembled T1SS has not been reported, hindered by the transient nature of these systems116, and should be the focus of future research to expand our understanding of TolC’s role in the secretion process, revealing how TolC interacts with other inner membrane transporters and periplasmic adaptor proteins, and shedding light on the molecular mechanisms underlying substrate translocation across the bacterial envelope. Additionally, the mechanisms underlying T1SS assembly are not well understood, yet the interaction of the substrate with the inner membrane transporter is considered to trigger assembly, with conformational changes in the periplasmic adaptor protein recruiting TolC117.

As a component of T1SSs, TolC has a clear role in virulence, secreting different toxins like HlyA and heat-stable (ST) enterotoxins, which are responsible for extraintestinal and diarrheal E. coli diseases, respectively11,118,119. In addition to cytotoxicity, HlyA alters the host’s inflammatory responses, suppressing cytokine production in epithelial cells in vitro120 and stimulating interleukin-1β release from cultured human monocytes121. By mediating the export of HlyA, TolC is associated with modulating the innate immune response during infections. This has been further demonstrated by reduced expression of interleukin-1β mRNA in epithelial cells incubated with extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) lacking tolC122.

Mutants of Enteroaggregative E. coli lacking tolC also show reduced aggregative adherence123, and ExPEC tolC mutants demonstrate attenuated epithelial cell invasion in vitro122. TolC-associated adhesion and invasion have also been demonstrated in Salmonella enterica, with tolC null mutants displaying reduced adhesion to epithelial cells and an impaired ability to invade macrophages124,125. TolC has also been linked to biofilm production in several species of Enterobacteriaceae, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, S. enterica Typhimurium, and E. coli123,126,127. The exact role of TolC in bacterial aggregation, adherence, and biofilm formation remains to be determined but likely involves the efflux abilities of this protein, as several inner membrane pumps that associate with TolC have also been associated with E. coli biofilm formation128. TolC and its associated efflux systems have also been shown to influence the formation of E. coli persister cells, enabling survival following exposure to environmental stressors such as antimicrobials92, leading to recurrent infections129.

TolC is also implicated in acid resistance, a critical adaptive mechanism that enables E. coli to survive the host’s gastrointestinal tract, particularly during the transition through the stomach, where gastric acid poses a significant barrier to bacterial survival. E. coli can survive at pH 2.0 for hours due to acid resistance mechanisms130. Several studies demonstrate that the fitness of tolC-deficient E. coli strains is impaired under acidic conditions, including during extreme acid survival88,90, the latter of which is associated with the glutamate-dependent (Gad) acid resistance system. The genes encoding the glutamate decarboxylase system (GadA, GadB) are not expressed in tolC mutants under acid conditions88. TolC-mediated survival under acidic conditions is associated with the efflux pumps EmrB and MdtB, which form complexes with this outer membrane channel88. Acidic environments also stimulate the recruitment of TolC into efflux assemblies98. Finally, the two-component EvgAS system, which upregulates tolC (Fig. 4), also upregulates the Gad system (reviewed in131). Thus, tolC plays an important role in E. coli acid survival, a phenomenon vital for the bacterium’s life cycle; however, the underlying mechanisms associated with tolC-dependent acid resistance remain poorly understood.

In summary, the multifunctional nature of TolC promotes E. coli virulence and survival under diverse environmental stressors in the host122,124, making it a critical factor for bacterial adaptability and a potential target for novel antimicrobial strategies.

Concluding remarks

TolC has emerged as an important contributor to E. coli physiology, with myriad functions attributed to this versatile outer membrane channel. From its role in multidrug resistance, membrane integrity, acid survival, and function in T1SSs, TolC has proven to be a remarkably multifaceted protein. Yet, despite decades of research, many functions remain understudied. While the structure of TolC within the diderm environment is well characterized, the processes governing its folding and insertion into the outer membrane still need to be fully understood. Additionally, while we now have increased insight into how this outer membrane channel complexes with several inner membrane efflux pumps and their periplasmic adaptor proteins, the molecular details associated with its interaction with other efflux systems and T1SSs remain unknown, in addition to the environmental cues stimulating recruitment and assembly into these complexes. Several studies associate TolC with E. coli membrane integrity and LPS composition in E. coli, yet further research is needed to elucidate the specific mechanisms underlying these associations. TolC also makes multifaceted contributions to virulence-associated processes in E. coli, mediating survival against various environmental host stressors. As a result, it is expected that E. coli strains lacking tolC would show reduced survival within the host environment. However, this hypothesis requires further experimental validation and investigation into the molecular mechanisms underpinning tolC-associated acid survival.

Responses