Developing a framework for tracking antimicrobial resistance gene movement in a persistent environmental reservoir

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance has become one of the greatest human health threats. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales are key examples of this threat, having spread rapidly worldwide across niches, making them difficult to track and monitor, and being associated with multidrug resistance and poor clinical outcomes with invasive infection1,2. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacterales is mainly conferred by hydrolyzing enzymes encoded by carbapenemase genes, which are often carried on mobile genetic elements (MGEs), allowing these to be rapidly shared between bacterial strains and species. This horizontal gene transfer, especially between environmental organisms and clinical pathogens, is driving much of the carbapenemase crisis, but genomic analysis tools have been limited in tracking and quantifying the dissemination dynamics of these important genes3,4.

In recent years, hospital wastewater plumbing has been identified as a major reservoir for antibiotic-resistant pathogens to evolve, with sink drains frequently implicated in the spread of hospital-acquired infections, and disease outbreaks1,5,6,7. Water system biofilms in sink drains and traps are a unique ecosystem for nosocomial pathogens, where survival and proliferation are often facilitated by the selective pressure exerted by the disposal of antibiotics and the use of disinfectants8,9,10. The complex microbial diversity of this environment provides opportunities for AMR gene movement and sharing between bacteria via horizontal gene transfer of transposons and conjugative plasmids11,12.

In 2007, with the introduction of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing organisms (KPCO) to our hospital, we had previously described complex blaKPC transmission dynamics within patients through transposon and plasmid sharing across 62 unique bacterial strains from the first 181 patients known to be affected13. As wastewater premise plumbing represented a major KPCO reservoir and a plausible contributor to transmission14, we implemented environmental surveillance in 2013 to detect KPCO in sink drains, sink p-trap water, as well as toilet/hopper lids and water, in intensive care units across our institution.

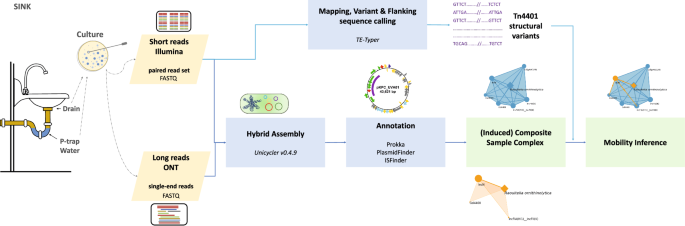

In this report, we present our findings from all longitudinal KPCO isolates from drain swabs and p-trap water collected from six sinks in four different medical ICU rooms over five years. Using both long- and short-read whole genome sequencing to generate complete hybrid assemblies with circularized chromosome and plasmid sequences, we successfully reconstructed their full-length sequences. These circularized sequences were annotated using bioinformatics tools to investigate their genetic content and relatedness. The information was then integrated into a mathematical framework called the “Composite-Sample Complex”, which captures the co-occurrence of chromosomal and plasmid contigs and enables us to deduce gene mobility and directionality patterns from a collection of isolates (Fig.1).

Long and short reads sequenced from isolated DNA extracts are hybrid assembled to reconstruct circularized plasmids and chromosomes. All circularized elements are then annotated using bioinformatics tools. This information is integrated into the Composite Sample Complex framework for mobility inference. The inferred mobility patterns are subsequently validated by checking the consistency of variants and flanking sequences.

Results

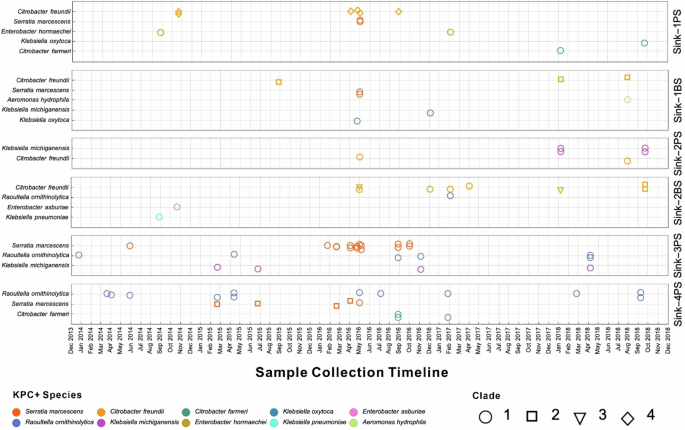

Drain swabs and P-trap water were sampled contemporaneously across six sinks in four ICU rooms at least three times annually within the five-year study period (286 sampling instances) with a KPCO-positivity rate of 20-40% for all rooms across all samplings. The longitudinal sampling resulted in 86 KPCO isolates across six sinks (51 drain/35 P-trap) from four rooms (See Supplementary Table 1). Eighty-two of the KPCO isolates (95%) were successfully assembled and included in the analysis (Fig. 3). The four excluded isolates were left out for the following reasons: (1) not viable from frozen stock, (2) no longer blaKPC PCR positive on subculture so presumed loss of plasmid in passage and (3) two isolates failed sequencing.

Distribution of species and strains

Ten unique blaKPC-positive species were identified in the drains and P-traps. Serratia marcescens was the most frequently isolated species, accounting for 24/82 sequenced isolates (29%), and Citrobacter freundii and Raoultella ornithinolytica the next most common, with 19 isolates each (23%) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figure). Across all species, we identified 14 distinct clades (based on a threshold to define a clade of >400 SNVs) including four C. freundii clades and two S. marcescens clades (Fig. 2). Given how genetically distinct clades were from each other, blaKPC presence across species/clades was most consistent with multiple horizontal transfer events15,16.

Composition of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) positive species (outer circle) and unique clades within species (inner circle) for the environmental samples collected from all units (Left), and in each respective sink (Right).

We observed distinct species/clade compositions in the unique sinks across different units. Four of the ten species were exclusively confined to one of the sinks, namely Enterobacter hormaechei in Sink-1PS, Aeromonas hydrophila in Sink-1BS, and Enterobacter asburiae and K. pneumoniae in Sink-2BS (Fig. 2).

The remaining six species were shared across multiple locations, but certain clades were specific to particular sinks (e.g. S. marcescens clade 2 in Sink-4PS, C. freundii clade 4 in Sink-1PS, and C. freundii clade 3 in Sink-2BS). Additionally, species/clade composition within some sinks either changed over time as well as observing several clades persisting for the five-year duration in a single sink (Fig. 3). These findings suggest that KPCO dynamics within sinks vary substantially from sink-to-sink with each sink fixture undergoing distinct evolutionary processes with some degree of independence.

Isolates are plotted according to collection date (horizontal axis) and sampling location (vertical axis, indicated by box on the right). Each isolate is represented as a data point, differentiated by color to indicate the species and by shape to denote specific strains.

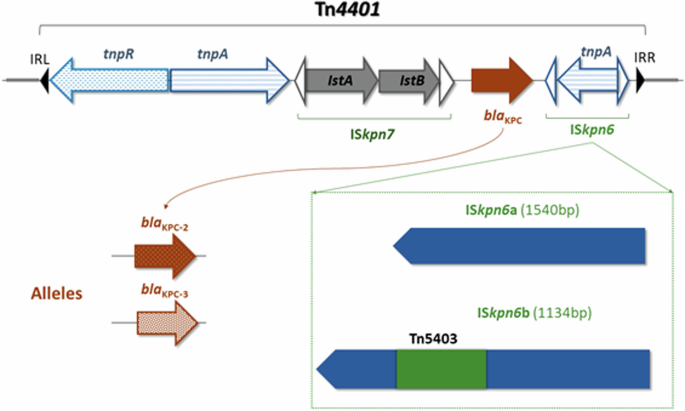

Complex, nested variation in the genetic context of bla

KPC

To assess the dynamics of horizontal transfer of blaKPC within environmental isolates, we examined variation in blaKPC and its genetic environment. blaKPC is typically carried in a highly conserved replicative 10 kb transposon, Tn440117, which can also be mobilized as part of a complex nested, Russian doll-like system by plasmids and other mobile genetic elements such as insertion sequences and other transposons3. Within Tn4401, ISKpn7 is typically located upstream of blaKPC with the same orientation, while ISKpn6 is positioned downstream of blaKPC in the opposite orientation (Fig. 4). Both ISKpn6 and ISKpn7 can function as mobile genetic elements18,19.

Arrows indicate the location and orientation of each gene within Tn4401, with blaKPC flanked by ISKpn6 and ISKpn7. The left panel summarizes the variations of blaKPC-2 and blaKPC-3. The right panel shows two isoforms of the ISKpn6: ISKpn6a and ISKpn6b. ISKpn6a closely aligns with the wild-type ISKpn6 sequence in the ISFinder database. In contrast, ISKpn6b features a unique insertion of Tn5403 at nucleotide position 406 of ISKpn6.

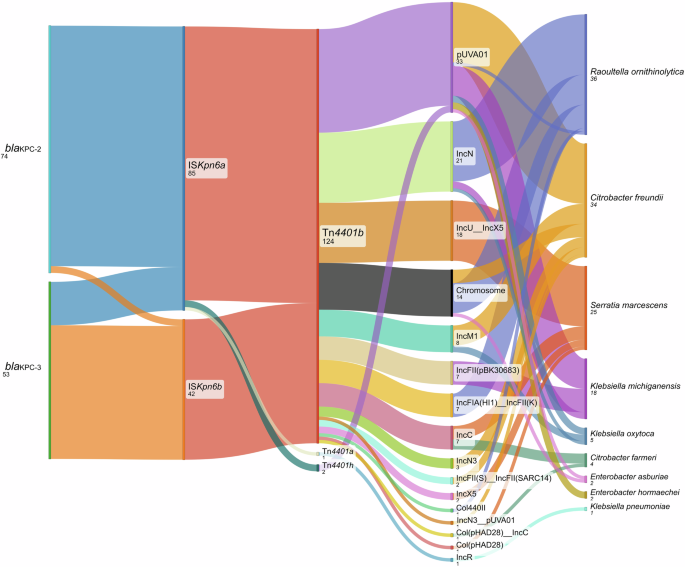

In this study, two blaKPC alleles were identified in three known Tn4401 variants, with additional variation observed in the insertion sequence, downstream of blaKPC (i.e. ISKpn6). These composite transposons were seen across 113 different plasmids, some of which were shared across species/clades (Fig. 4). Overall, with the many varied genetic contexts of blaKPC within this data set demonstrates a complex history of gene mobilization across species and plasmids at several trackable genetic levels; allele, Tn4401 structural variant with and without Tn5403 insertion, replicon typed plasmid and species (Fig. 5).

The layers we considered (from left to right) were the blaKPC gene, the ISKpn6 insertion sequence downstream of blaKPC, the transposon Tn4401, associated plasmids, and the host species. Vertical bars represent the distribution of variations at each level. Bands represent the association between two adjacent levels.

The distribution of the two blaKPC alleles identified (blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3; differ by one SNV) could not clearly be attributed to any single factor such as unit/sink location, species/clade, or mutation given the different wider genetic contexts (Supplementary Table 2). None of the 82 isolates carried both blaKPC-2 and blaKPC-3 simultaneously, as observed previously20. Different isolates of the same clade did however harbor different blaKPC alleles. For example, one clade of K. michiganensis had blaKPC-2 on the pUVA01 and IncFII(pBK30683) plasmids in one isolate sampled from Sink-3PS, and blaKPC-3 on the pUVA01 and IncN plasmids in two other isolates from the same sink.

The robust association between the blaKPC gene and ISKpn6/ISKpn7 within Tn4401 is well-documented in the literature18,21,22. Among the 82 isolates, we identified two structural isoforms of ISKpn6: ISKpn6a and ISKpn6b. The genomic characterization of these two isoforms revealed more intricate rearrangement structures within our collection ISKpn6a closely aligns with the wild-type ISKpn6 sequence in the ISFinder database. In contrast, ISKpn6b exhibits a novel insertion of Tn5403 at nucleotide position 406 of ISKpn6 (Fig. 3). ISKpn6a was the most prevalent isoform in environmental samples, found in 62 isolates across all 10 bacterial species, 14 clades, and 12 of the plasmid Inc types. It was observed in all 6 units Dec 2013-Sep 2014. In contrast, ISKpn6b was confined mainly to specific species (R. ornithinolytica, K. oxytoca, K. michiganensis), and plasmid Inc types (IncFIA(HI1)__IncFII(K), IncN, IncM1, Col440II), predominantly observed in units Sink-4PS and Sink-3PS, and from Mar 2014 to Sep 2018. The average copy number of blaKPC when associated with ISKpn6b was noted to be significantly higher than when associated with ISKpn6a (1.39, stdev [0.57] versus 1.82 [stdev: 0.59]; p = 0.003, Wilcoxon rank sum test). This observation is consistent with the hypothesis that Tn5403 enhances the transposition capability of blaKPC, as has been demonstrated in vitro23.

As blaKPC is always contained within Tn4401 in our dataset, we identified structural variation, single-nucleotide variation (SNV), and flanking sequences of Tn4401 across the environmental samples to track and validate the mobilization events of blaKPC. The Tn4401 isoforms all differ in the region upstream of the blaKPC24. Among 82 isolates, there were three structural variants of Tn4401, namely, Tn4401b, Tn4401a, and Tn4401h in 79 (96.3%), 1 (1.2%), 2 (2.4%) isolates, respectively. All structural variants carried blaKPC, but they exhibited different deletions in the promoter region upstream of blaKPC as previously described24. Tn4401b was the most prevalent variant, being found in 8/10 species, widely spreading across all sampled sinks.

Using replicon typing as a crude metric of plasmid diversity, there were 113 blaKPC-carrying plasmids across 15 distinct known replicon types [as well as the non-typeable but characterized plasmid pKPC_UVA01 (repA_CP013325)]16,25. The top 3 Inc types associated with blaKPC carriage were pKPC_UVA01 (in 33 samples), IncN (in 21 samples), and hybrid IncU__IncX5 (in 18 samples). These major KPC-carrying Inc types were shared across different units supporting the concept that blaKPC was acquired by the plasmid outside of a specific study sink, with pKPC_UVA01, IncN, and IncU__IncX5 observed in 5, 4, and 4 sinks, respectively. The IncU/IncX KPC hybrid plasmid was only identified in one clade of S. marcescens (across multiple sinks), suggesting vertical transmission and persistence of a blaKPC plasmid within this S. marcescens clade over time. In contrast, pKPC_UVA01 was shared across 5 species, and in 25/33 of isolates blaKPC had more than one genetic context consistent with blaKPC dissemination via horizontal gene transfer through transposition and plasmid transfer in this genetic context.

Given the diversity of genetic contexts for blaKPC that were observed, we applied our framework to characterize the putative mobilization events that contributed to this complex diversity.

Characterizing bla

KPC transfers by building a composite-sample complex model

To capture the complex dynamics of blaKPC movement and evolution within a relatively stable environmental source we took a novel approach. We treated each isolate as a collection of co-occurring circularized genomic elements (either chromosomes or replicon type labeled plasmids), and as an evolutionary snapshot where the genomic element could be a source or a target of blaKPC. We then developed a mathematical framework of plasmid chromosome co-occurrence called the “Composite-Sample Complex” (CSC) (See Method Section and Supplementary Fig. 4). This framework enables us to deduce gene mobility and directionality patterns from a collection of isolates. The primary principles are that only one plasmid replicon type or chromosome can exist in any instance and, blaKPC can be integrated into or from any genomic context. Each CSC constitutes the union of all isolates in the collection which is being investigated (e.g. within a single clade, or a single sink), the vertices are the individually labeled plasmids/chromosome, vertex weights are determined by the number of isolates that contain that specific element in the collection, and the weight of the number of vertices with blaKPC indicates origin versus source. By integrating replicon typing information and treating all closed genomic elements within a bacterial cell as a potential target for resistance integration, the Composite-Sample Complex ensures reliable identification of these mobility patterns. Moreover, this framework assists in accurately pinpointing the source and target of gene mobility.

Transposition: plasmid to chromosome

We observed the integration of blaKPC into the chromosome in C. freundii (in 4 samples), R.ornithinolytica (in 9 samples), and E. asburiae (in 1 sample). Interestingly, while C. freundii and R. ornithinolytica were shared across different units, the genomic KPC-carrying integration site in the chromosomes was specific to each sink, with C. freundii found in Sink-1PS and R. ornithinolytica in Sink-4PS, suggesting that these integrations into chromosome took place in sink specific environment. This is an important biological validation as chromosomes, by definition, will not mobilize into another species or strain like a mobile plasmid. The CSC is then further supported in the finding that the genomic context of chromosomal integration is unique to the specific sink.

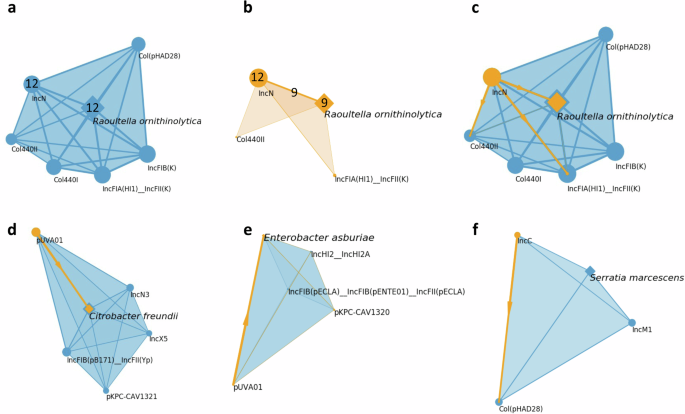

We can successfully hypothesize the source of blaKPC transposition for each of these integrations, as depicted in Fig. 6. To elucidate our approach, we use the KPC integration into the R. ornithinolytica chromosome in unit Sink-4PS as an illustrative example of the model. Within unit Sink-4PS, 9 out of 12R. ornithinolytica isolates harbor blaKPC in their chromosomes, all of which are associated with KPC-carrying IncN plasmids (Fig. 6a, b). Even among the remaining R. ornithinolytica isolates lacking blaKPC in their chromosomes, they still possess KPC-carrying IncN plasmids. Furthermore, no other KPC-carrying plasmid displays such a high degree of co-occurrence with KPC-carrying R. ornithinolytica chromosomes. Hence, we posit that the IncN type is the origin of KPC transposition into R. ornithinolytica chromosomes (Fig. 6c).

The size of the vertices and the width of the edges are proportional to their weights. (a-c) KPC mobility pattern within Raoultella ornithinolytica from Sink-4PS. These figures represent a composite analysis of all twelve isolates of R. ornithinolytica obtained from Sink-4PS. a CSC derived from the composite sample, numbers associated with IncN and R. ornithinolytica encode the number of occurrences of IncN plasmids and R. ornithinolytica chromosome. b KPC-induced CSC derived from same the composite sample with numbers denoting the frequency of IncN plasmids and R. ornithinolytica chromosomes that are KPC-carrying. The number on the edge between IncN and R. ornithinolytica indicates the count of their co-occurrences. c the inferred mobility patterns of KPC from the composite sample are shown. In addition to the IncN to R. ornithinolytica pattern, we also identify IncN to Col440II and IncN to IncFIA(HI1)_incFII(K) mobility patterns from the same composite sample. d The CSC of all Citrobacter freundii from Sink-1PS, we identified pKPC_UVA01 to C. freundii chromosome KPC mobility pattern from this CSC. e The CSC of all Enterobacter asburiae isolates from Sink-2BS, we identified pKPC_UVA01 to E. asburiae chromosome KPC mobility pattern from this CSC. f The CSC of all Serratia marcescens isolates from Sink-4PS, we identified IncC to Col(pHAD28) KPC mobility pattern from this CSC.

To validate the hypothesized transposition pattern, we examined the variations of blaKPC and its surrounding genetic elements in both the source and target. We then checked for consistency between them (Table 1). Specifically, the co-occurring IncN plasmids and R. ornithinolytica chromosomes both possess blaKPC-3, which is flanked by ISKpn6b and further surrounded by Tn4401b. This arrangement is in agreement with the notion that the IncN plasmid type serves as the origin of KPC transposition onto the chromosomes of R. ornithinolytica. Additionally, we examined the 5 bp flanking sequence of Tn4401. The variations in the flanking sequence of Tn4401 indicate that the mobilization of the KPC occurred through the transposition of Tn4401, see Table 1 line 1. We further validated that the blaKPC/Tn4401 integration occurred at the same genomic location on their chromosomes across all the 9R. ornithinolytica isolates.

Using a methodology analogous to our earlier approach, we analyzed the CSCs and KPC-induced CSCs constructed from isolates of the same bacterial clade from a particular sink across all possible strain-sink combinations. We successfully identified two other KPC plasmid-chromosome transposition pathways: from pKPC_UVA01 to C. freundii in unit Sink-1PS (Fig. 6d), and from pKPC_UVA01 to E. asburiae in unit Sink-2BS (Fig. 6e). Again, these transposition pathways are supported by subsequent validation (Table 1) from the genomic context. Notably, all identified KPC plasmid to chromosome transposition patterns are sink-specific, consistent with transpositions within the specific sink drain/ptrap, highlighting that this mobilization is potentially occurring while in the environment.

Transposition: plasmid to plasmid

In addition to chromosomal transposition events, we identified plasmid-plasmid transposition pathways of blaKPC. Three distinct pathways were observed in unit Sink-4PS: IncN to Col440II, IncN to IncFIA(HI1)__IncFII(K) in R. ornithinolytica (Fig. 6c), and IncC to Col(pHAD28) in S. marcescens (Fig. 6f). The co-occurring IncN and Col440II plasmids, as well as the IncN and IncFIA(HI1)/IncFII(K) plasmids, consistently carry blaKPC-3, which is flanked by ISKpn6b in a Tn4401b isoform. Meanwhile, the co-occurring IncC and Col(pHAD28) plasmids all carry blaKPC-3 with ISKpn6a wild type.

These findings provide insights into the distinct plasmid-to-plasmid transposition pathways, utilizing the genetic consistency of blaKPC and associated mutations within each pathway to provide additional validation support to the model. The observed transposition events contribute to the understanding of blaKPC dynamics within the specific environment of unit Sink-4PS, emphasizing the diversity of plasmid types involved in the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance genes. The results were derived from the evaluation of the CSC and then validated with complete closed genomic data and emphasized the ongoing real-world evolution of strains in the environment over time with a focus on a single gene as a proof of concept.

Conjugation

To understand potential transfer of genetic material between bacterial strains within sinks, we investigate the CSC and the KPC-induced CSC constructed from all the isolates collected from each individual sink (Supplementary Fig. 3). Through our construction, replicon types situated at the junction of the CSC may indicate the presence of conjugative plasmids, given these replicon types are shared among multiple species. We observed that pKPC_UVA01 appears at the junction of the composite sample complex in 4 out of 6 sinks. This observation aligns with prior findings, which suggest that pKPC_UVA01 is highly conjugative and plays a pivotal role in the outbreak of KPC dissemination within our hospital16. Notably, C. freundii is the only species common to these four rooms, and nearly all C. freundii isolates carry pKPC_UVA01. Consequently, we hypothesize that C. freundii serves as the source of pKPC_UVA01 conjugation.

Another plasmid, Col(pHAD28), could also be considered highly conjugative by this model but also consideration needs to be given for this plasmid being stably carried by many isolates before introduction of blaKPC. It has been previously observed that a Col(pHAD28) type plasmid p3223 being shared across many species of Gammaproteobacteria in both UVA hospital isolate collection and NCBI’s global collection, and could have synergistic relationships with large KPC-carrying plasmids26. Our initial screening suggests that the majority of the Col(pHAD28) plasmids in our environmental isolates have identical or similar length with p3223, supporting the hypothesis that they are related via conjugation. However, we do observe length variation in some of the S. marcescens and K. michiganensis isolates, suggesting they are undergoing frequent rearrangements. Following a similar line of reasoning, we see that S. marcescens is the likely source of Col(pHAD28) conjugation.

Discussion

Due to frequent rearrangements, plasmids diverge from the conventional tree-like evolution possible with single nucleotide variants accumulating at random in a genome which allow for Bayesian inferences of evolutionary pathways. Consequently, global alignment-based methods and traditional phylogenetic inference are unsuitable for studying plasmid evolution27. Current methods that investigate transposition primarily focus on identifying similar subsequences that exhibit a certain degree of co-occurrence on different plasmid contigs. However, even with the identification of conserved patterns, it remains insufficient to reconstruct the transposition pathway. Here we use a relatively stable environmental niche over a five-year period to carefully observe some of the complex evolution occurring within bacterial strains all sharing a tractable genetic element (i.e. blaKPC) to describe some of the complexity and as a first step to building a new approach evolution driven by mobile genetic elements. The method uses the co-occurrence of a collection of plasmids with a chromosome in an isolate as an evolutionary snap shot of potential targets and donors of blaKPC. We then label the elements which have blaKPC and use probability within which to make inferences about the directionality and movement of a specific gene within or across bacterial strains over time. This approach recognizes that a collection of plasmids and a specific bacterial chromosome is not randomly assembled but maintained as a collection of circularized genomic contents by vertical bacterial replication in which gene mobility can occur or be introduced. Although this model may be imperfect and require validation to be definitive, it could be scalable and used for hypothesis building around the origin and directionality of mobile genetic elements and their associated genes.

As described in the first portion of the manuscript, there is so much diversity in the genomic context of this single gene in a single built environment that manually lining up 82 isolates, and the hundreds of plasmids can feel like a challenging and confusing effort on which little biologic speculation about directionality can be established. Using this hypothesis-building tool, we have been able to organize the plasmids to estimate mobility and then confirm with additional data and metadata (sink location, species). In this effort, we have successfully discerned sink-specific KPC mobility patterns within and across clades, including integrating blaKPC into chromosomes. Based on the data, this likely occurred within the sink wastewater environment in more than one case. Integration into the chromosome is a hypothesized method for maintaining important genes within a bacterial cell28, and here we demonstrate this occurrence and the natural environment for the mobility to occur. Finding these real-world instances can provide additional clues to validate the location and setting where this antimicrobial resistance evolution is taking place.

Aside from successfully applying a novel approach to the antimicrobial resistance movement, there are several additional biological findings. Tn5403 was identified in K. pneumoniae as a ‘helper element’ enabling mobilization of non-conjugative plasmids via cointegrate formation23,29 and demonstrating real-world validation of increased mobility associated with another transposon which had demonstrated this in a laboratory model23. This further supports our approach to trying to build a model which can detect enhanced movement and evolutionary history as critical in understanding antimicrobial resistance gene dissemination. Interestingly, the isolates that predominately demonstrated this mobility were centered in one unit over the other, and generally, what we have found is that the predominating KPC-producing species found in the premise plumbing and in patients does vary by unit, although the etiology of the variation is not completely clear30,31. We have previously examined factors which drive KPC-producing organisms to be found in our drain and p-trap and found that the drain or p-trap being previously positive was the strongest factor but that new patient seeding occurred about 6% of the time32. Another major factor driving sink positivity was tube feeding, which aligns well with our finding in the sink lab that protein-containing nutrients increase positivity and may support replication and heavier growth and that infrequent use may be contributory at the drain level but that antimicrobials or several other clinical factors were not significant33. The drivers of variation in this environmental data set do not appear to be related to patient characteristics as these were both medical ICUs throughout the period with similar hand hygiene rates, soap, environmental services practices and staffing between the units during this period. One striking difference between the units is that Sink-4PS and Sink-3PS, where the Tn5403 activity was highest, were established in 1981 and were likely seeded by patients earlier34 as Sinks 1 and 2 were in a newer adjacent hospital tower which opened in 2012 well after patients with KPC had been admitted to our hospital in 2007 so potentially seeding newer plumbing but at a later time point. Although there is still so much that remains unknown about drivers that promote resistance gene mobilization decreasing carbapenemase-producing organisms in the drains and thereby further limiting evolutionary opportunities within the drains would be to avoid nutrient disposal, use the sink frequently and avoid newly seeding the drains with new patient strains although these can be challenging to implement practically in a hospital32,35. Additionally, future research should aim to integrate gene movement with some of these factors to understand the infection control and clinical drivers of resistance gene mobilization.

As long-read sequencing becomes widely available and easily accessible in both research and clinical settings, there is an anticipation that the ability to assemble mobile genetic elements within their true genomic context will rapidly expand as the context of mobile elements is often not available with short-read data. However, we still need new approaches to assess and track the movement of those elements within and between bacterial cells to understand the evolutionary processes. Here, we have taken a spatiotemporally confined fully sequenced longitudinal collection of multi-species bacterial isolates that harbor the same carbapenemase gene from a persistently colonized environmental reservoir to look first at blaKPC gene mobility within and across strains combining scientific and genetic principals to create an informed mathematical model for hypothesis generation and testing. Our CSC model employs simplicial complexes, which extend the concepts of networks and hypergraphs to model higher-order relationships in real-world data sets36. This sophisticated mathematical framework, as the foundation of topological data analysis37,38, has been successfully applied in fields such as network science, computational biology39,40, medical imaging41 and biomedicine42, demonstrating its utility and effectiveness. Here, we tested and validated this novel approach which we believe could be deployed more widely to understand antimicrobial resistance evolution as it has first been vetted on this smaller well curated data set.

There are several limitations to the approach and there will need to be an assessment of its future scalability to larger data sets. First, replicon typing serves as an informative means to classify plasmids, as two different plasmids containing the same replicon are incompatible in the same cell. However, relying solely on replicon typing to infer evolutionary closeness can be misleading, as two evolutionarily independent plasmids which have long been carried by unique strains may still share the same type. In the future, we could integrate additional plasmid markers to better define distinct plasmids especially when applying the CSC across strains and species. The conjugative nature of plasmids further complicates tracking gene mobility on plasmids through replicon typing, as demonstrated that we were unable to completely work out the mechanisms of movement for Col(pHAD28) (i.e. frequent co-mobilization with other plasmids versus long term carriage by many strains versus source of blaKPC transmission between cells). Lastly, we have not aligned the temporal nature of the isolates to further support the evolution over time as this was not possible. In some cases, structures that would be the source were identified in isolates later than isolates with target structures. We anticipate that while events such as transposition may be occurring in the sink drain, there is likely a mixed population, which will result and without sequencing multiple colonies from each isolation this mixed population may be overlooked43.

In conclusion, we report a targeted genomic characterization of KPCOs isolated from our hospital’s wastewater plumbing environment over a five-year sampling frame to understand resistance gene sharing using a novel method. The evolutionary tools we currently have to describe mobile genetic elements among bacteria remain limited, we were able to demonstrate plausible KPC gene movement within and across clades with a data set paired with a novel mathematical approach. We believe this type of approach could be more widely used to understand the importance of bacterial gene sharing and evolution driven by mobile genetic elements in many future contexts.

Methods

Sampling methodology and approach

As a part of an on-going surveillance of premise plumbing sources at our institution, we collected samples from wastewater sites of sink plumbing environment (drain swabs and p-trap water) from six sinks in four medical intensive care rooms across two units between Dec-2013 and Dec-2018. The four rooms were selected based on their persistent colonization over time, room occupancy of clinically similar patients, Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU) sink status and lack of physical intervention to exchange plumbing within the timeframe. In particular, from an infection control perspective, there was no significant difference in the species identified among patients in the selected units. Rooms with Sinks- 1PS, 1BS, 2PS, and 2BS were situated in MICU which opened in 2012 and rooms with Sinks- 3PS and 4PS were in another MICU which opened in 1981 (Supplementary Data Table 1 and Supplementary Data Fig. 1). All sinks had similar designs with oval uniform Corian® (DuPont) bowl with an overflow.

All collected samples were processed to capture KPC-positive isolates, as previously described14. All isolates shown to be phenotypically positive for carbapenemase production44, were subjected to real-time PCR to detect blaKPC.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS)

All viable confirmed blaKPC positive isolates underwent short-read sequencing on Illumina HiSeq2000 instrument as previously described44. Long read sequencing was performed on the MinION platform using the Spot On MK1 R9 version flowcells (Oxford Nanopore, Oxford, UK). Library preparation was done using the native barcoding kit (EXP-NBD104) and ligation sequencing kit (SQK-LSK109), following the manufacturer’s protocol (Native barcoding genomic DNA protocol).

Bioinformatics analysis

Illumina WGS data analysis

The quality controls steps for raw Illumina short-reads included adapter removal using Trim Galore (v0.6.4; parameters: –length 35 –stringency 5)45, followed by trimming the low-quality tails using Trimmomatic (v0.39; parameters: TRAILING:20 SLIDINGWINDOW: 4:20 MINLEN:70)46. Species identification was performed by calculating the genomic distances of the read sets against a collection of complete assemblies in NCBI’s RefSeq database using MASH47(v2.1). The closest matched reference genome for each species was used to perform alignment using bwa mem48 and variant calling using freebayes v1.2.049, as implemented in SNIPPY50 (v4.6.0). Within each species, pairwise whole-genome single-nucleotide variant (wgSNV) distances were calculated, and maximum-likelihood phylogenies for each species were built on the SNV-site alignments using IQ-TREE (v2.1.3; substitution model: GTR + ASC)51,52, followed by joint ancestral reconstruction with pyjar53,54 (v1.0). Cluster of isolates within 25 wgSNVs of each other were considered to be clonal based on short read data. The multilocus sequence typing based on (usually) seven house-keeping genes was performed on de-novo assembled contigs generated using SPAdes55,56,57 (v3.15.4).

De-novo hybrid assembly

Using the high-quality Illumina read sets as a reference, the raw Nanopore long-reads were quality filtered using Filtlong (v0.2.0) for higher quality subset of long reads58. Fully resolved bacterial assemblies were reconstructed from the high-quality long and short read data using the hybrid-assembly approach implemented in Unicycler (V0.4.9)59. The assemblies were annotated using Prokka60 (v1.14.6). Replicon-based incompatibility group typing was performed using PlasmidFinder61 (v2.1), against the Enterobacteriaceae database accessed: Feb 2020(parameters: -mincov 0.50 –threshold 0.80). Acquired antimicrobial resistance genes were screened using NCBI’s AMRFinder tool v3.6.762, which relies on a curated AMR protein database and a collection of hidden Markov models (parameters: –ident_min 0.90 –coverage_min 0.50). Identification of insertion sequences was performed using ABRicate v0.8.1163, against the ISFinder database (accessed: Feb 2020) (parameters: –mincov 50 –minid 80)64.

Targeted transposon evaluation

We performed a targeted evaluation of transposons, which play pivotal roles in the mobilization of blaKPC27. Tn4401 has been reported to have at least six isoforms (designated as a, b, c, d, e, and i). These isoforms are characterized by distinct deletions, predominantly found upstream of blaKPC24,65. To delve into the intricacies of Tn4401, we applied the TETyper tool (v1.1) to short-read sequencing data, to detect and characterize single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and deletions within Tn4401, enabling us to track specific isoforms of the transposon as well as to understand the genetic contexts they inhabit flanking inverted repeats which are the 5-bp TSD generated with Tn4401 insertion into a new genetic context as a marker of movement66.

We also consider another transposon, Tn5403, which has been shown to integrate into Tn4401 downstream of blaKPC on multiple occasions in epidemiologically unique settings29,66,67,68. Tn5403 is a 3,663 bp Tn3-family transposon that mobilizes via replicative transposition with 5 bp TSD23. To identify the genetic variations of Tn5403, we perform the Smith–Waterman local alignment algorithm69 to all assembly sequences, with reference sequences retrieved from the TnCentral database66,69.

The composite-sample complex

The Composite-Sample Complex represents a mathematical framework for integrating the information obtained from replicon typing and the associated closed plasmids and chromosomal contigs to conceptualize evolutionary events of blaKPC of transposition events.

Given a collection of isolates (C={{S}_{1},,ldots ,{S}_{m}}), the Composite-Sample Complex ((Xleft(Cright),,{w}_{C})), where (Xleft(Cright)) is a simplicial complex and ({w}_{C}) is a collection of simplex weights, is constructed as follows (see Supplementary Fig. 4 for an illustrative example):

-

1.

Contigs labels: For each isolate, (S), label each contig with its species name (chromosome) or replicon type (plasmid). Since each isolate contains only 1 chromosome contig and distinct plasmid contigs that cannot share the same replicon type due to incompatibility. This contig labeling is effectively an injective mapping to a collective set of species names and replicon types sorted by hybrid closed genomic data from each isolate. Consequently, an isolate is represented as a set of contig labels of plasmids and chromosome, (S={{a}_{1},,ldots ,{a}_{n}}). In this framework it is possible for labels to be shared across different isolates (e.g. IncN plasmid in multiple isolates) but does not necessarily infer that they are the same plasmid across the collection.

-

2.

Initialize with 0-Simplices (Vertex Set): the 0-simplices constitute the union of all isolates in the collection (C), each represented as a set of labels. The weight of a specific vertex, (a), denoted as ({w}_{C}(a)), equals the number of isolates in (C) that contain a specific contig (a).

-

3.

Step up in dimension: higher-dimensional simplices and their weights are constructed analogously. A (k)-simplex, (sigma ={{a}_{1},,ldots ,{a}_{k+1}}), is part of (Xleft(Cright)) if there exists at least one isolate, (S{prime}), in (C), where (sigma) is a subset of (S{prime}). The weight of (sigma), ({w}_{C}left(sigma right)) represents the number of isolates where ({a}_{1},,ldots ,{a}_{k+1}) occur together. This expression is used to quantify the co-occurrence of certain elements within a given set of isolates.

The KPC induced composite-sample complex

Here we construct a model to understand the movement of a gene via transposition within an isolate and a collection of isolates using frequency of the contig with and without the gene to assign a weight (w). Suppose we are given a Composite-Sample Complex ((Xleft(Cright),,{w}_{C})) and gene ({KPC}), the Induced Composite-Sample Complex (({X}^{{KPC}}left(Cright),,{w}_{C}^{{KPC}})) is constructed as follows (see Supplementary Fig. 4 for an illustrative example):

For any simplex (isolate) (sigma ={{a}_{1},,ldots ,{a}_{k+1}}) in X(C), the ({KPC})-induced weight, ({w}_{C}^{{KPC}}left(sigma right)) counts the number of isolates where ({a}_{1},,ldots ,{a}_{k+1}) co-occur, and each ({a}_{i}) in the isolate carries ({KPC}). The induced complex, ({X}^{{KPC}}left(Cright)) contains all simplices (sigma), such that ({w}_{C}^{{KPC}}left(sigma right) > 0).

This construction allows for the examination of relationships and co-occurrences specific to contigs carrying the ({KPC}) gene.

Inferring KPC mobilization

The key idea is to consider both: the Composite-sample complex and the ({KPC})-induced composite-sample complex. This provides the contextual framework for analyzing transposition events associated with g. Given a CS complex ((Xleft(Cright),,{w}_{C})) and two contig labels (A) and (B), we introduce the following criterion (#):

-

1.

Target deficiency: ({w}_{C}^{{KPC}}left(left[Bright]right) ,< ,{w}_{C}(left[Bright])). Indicates that not all contigs (B) carry KPC.

-

2.

High degree of co-occurrence: ({w}_{C}^{{KPC}}left(left[A,Bright]right)=,{w}_{C}^{{KPC}}left(left[Bright]right)). Every time we observe (B) carrying KPC, we also observe (A) carrying KPC in the same isolate.

-

3.

Source redundancy: ({w}_{C}^{{KPC}}left(left[A,Bright]right) ,< ,{w}_{C}^{{KPC}}left(left[Aright]right)). KPC-carrying (A) does not always co-occur with KPC-carrying (B).

Suppose for a pair ((A,B)), the criterion (#) holds, then we alert to a potential transposition event mobilizing KPC from (A) to (B) in the composite sample (C). The comparison of these complexes enables us to systematically and efficiently formulate testable hypotheses, which will subsequently undergo validation through the examination of nucleotide and structural variations of blaKPC genetic environments.

Validation of KPC mobilization

We applied our method on UVA environmental data to infer KPC mobility patterns. To bolster the credibility of the hypothesized mobilization event, a thorough validation process is essential which was done on this longitudinal environmental data set. This validation involves cross-checking the structural and nucleotide variations of KPC itself and the genomic environment of KPC between different contigs, reinforcing the reliability of the inferred gene mobility patterns.

The validation includes verifying the consistency of blaKPC and ISKpn6 variants between the source and target contigs. Additionally, because of the strong association between blaKPC and Tn4401, the TETyper results for Tn4401 can be utilized to validate the KPC mobility patterns that we deduced from the composite-sample complex. Moreover, by combining these two approaches, we can systematically reconstruct the relationship between variant-flanking sequence combinations and plasmids/chromosomes contigs, thereby gaining deeper insights into the transposition events.

Responses