The Tol Pal system integrates maintenance of the three layered cell envelope

Cell envelope structure in Gram-negative bacteria

The cell envelope of Gram-negative bacteria is a major barrier to antibiotic penetration. This complex structure comprises an asymmetric proteolipid outer membrane (OM), an underlying peptidoglycan (PG), and a cytoplasmic membrane. The multi-layered architecture of the cell envelope impedes antibiotic efficacy through several mechanisms; alteration of outer membrane protein (OMP) composition to hinder cellular entry, activation of efflux pumps to export antibiotics, modification of OM lipids to modulate permeability, and enzymatic inactivation via chemical modification1,2,3. Furthermore, antibiotic targets within the envelope can be modified to evade recognition, and their expression levels can be downregulated to diminish antibiotic efficacy. The robustness of the envelope is highlighted by four of the six leading pathogens contributing to the 1.27 million deaths associated with antibiotic resistance in 2019, being Gram-negative bacteria4. This underscores the urgent need to combat the growing resistance of Gram-negative bacteria, given that in 30 years it could be the leading cause of mortality worldwide5.

At the cell surface, the OM acts as a permeability barrier for antibiotics and small molecules. The functionality of the OM is intimately linked to its structural stability through a complex network of proteolipid interactions6. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is the major lipid class within the outer leaflet of the OM and is tightly packed with proteins that together block the entry of macromolecules. LPS is built from a heterogeneous polysaccharide O-antigen linked to core oligosaccharide and a lipid A moiety7. Many pathogenic species encode pathways for homo- and heteropolymeric O-antigen, which allows cells to modulate their virulence and pathogenicity8,9. Divalent cations crosslink LPS molecules to create a mesh that reduces the transit of small molecules up to 100-fold compared to a phospholipid bilayer10. The passage of small hydrophilic molecules through the OM is regulated by membrane-embedded porins11,12. In E. coli, OM porins form non-specific porous channels that have a permeability cut off of 700 Da11. This permeability cut off is even further reduced to 200 Da in pathogenic Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) and Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) whose porins are substrate specific13,14,15. The permeability and integrity of the OM is thus determined by the relative expression levels of embedded outer membrane proteins (OMPs), which constitute 1.5% of the E. coli genome16. This abundance of OMPs allows for function-specific turnover in response to environmental changes, enabling bacteria to adapt for survival17,18,19. The dynamic and robust nature of the OM poses a significant challenge to the development of effective antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria.

Beneath the OM, the PG affords structural stability to the envelope, protecting against turgor pressure and maintaining cell shape20,21. Synthesis and remodelling of the PG is essential during cell elongation and division20. Dynamic multiprotein complexes regulate PG growth in response to environmental changes and cell cycle. Defects in PG synthesis or remodelling often result in cell lysis. Thus, proteins involved in these processes such as PG synthases are targeted by beta-lactam antibiotics and other classes of antimicrobial agents22,23,24. Direct tethers between the OM and the PG provide additional support to cell envelope structure, safeguarding the distance between the two outer most layers. Tethers are often facilitated by lipoproteins that are anchored within the OM by N-terminally linked lipids and extend through the periplasmic space to bind PG (Fig. 1A). Braun’s lipoprotein (Lpp) is the most abundant lipoprotein forming covalent links to PG in E.coli25,26,27,28. In other Gram-negative species such as α-proteobacteria, integral OM proteins form covalent crosslinks to PG via a conserved N-terminal alanyl-aspartyl motif29,30. Non-covalent interactions are delivered through the OmpA family of proteins that differ from lipoproteins by forming beta-barrels that embed within OM and extend to bind to PG, thereby enhancing envelope stability28,31,32,33. Alterations in OM-tethering systems is proposed to drive loss of the OM during the evolution of monoderm bacteria from diderms34.

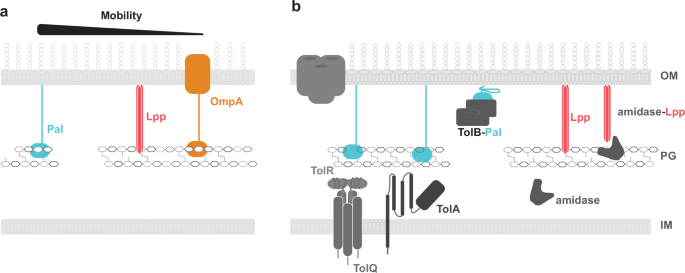

a E. coli OM is connected to PG by covalently bound lipoprotein, Lpp, and two non-covalently bound proteins lipoprotein Pal and OmpA, that both contain a OmpA-like PG binding domain,. The relative mobility of the lipoproteins, which allows them to be redistributed around the cell, is correspondingly illustrated above. b As a cell grows, divides, and responds to the changing environment, it requires constant remodelling of the OM-PG scaffold. In particular, modulations in the stabilising contacts afforded by lipoproteins. To redistribute Pal the other core proteins of Tol-Pal system form an envelope spanning complex to bind and mobilise PG-bound Pal, typically to the division site. For Lpp covalent crosslinks are removed from PG by Lpp-PG amidase.

Protein-facilitated connectivity within the cell envelope is also mediated by cytoplasmic membrane-anchored envelope spanning complexes. Coordination between the cytoplasmic membrane and OM is required to link processes at the energy-deficient cell surface to distal energy sources. These protein complexes spanning the periplasmic space can be stable or transient. Virulence factors, such as the type VI secretion machinery and structures such as the flagellum, form more stable connections that are coincident within both membranes35,36,37,38. In contrast, protein complexes that require energy for assembly, such as those involved in gliding motility, antibiotic efflux, LPS secretion, and nutrient import, are often transient39,40,41,42. The Tol-Pal system is a transient envelope spanning complex that is required for OM stabilisation during cell division43. This protein assembly harnesses energy from the proton motive force (PMF) across the cytoplasmic membrane to drive redistribution of lipoprotein Pal to the division site, which stabilises the OM during cell division through increased linkages to the PG.

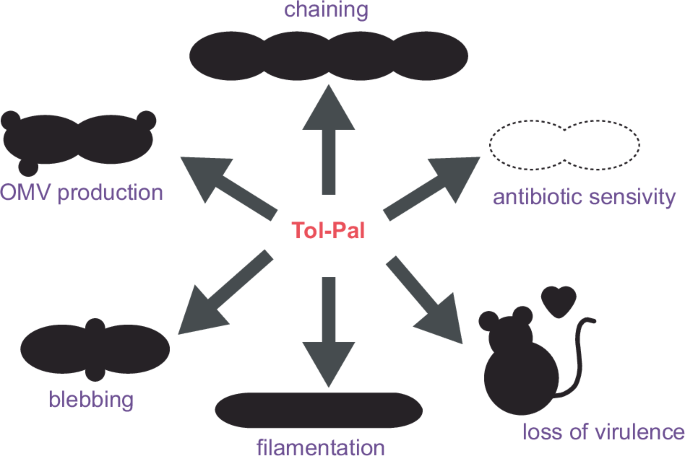

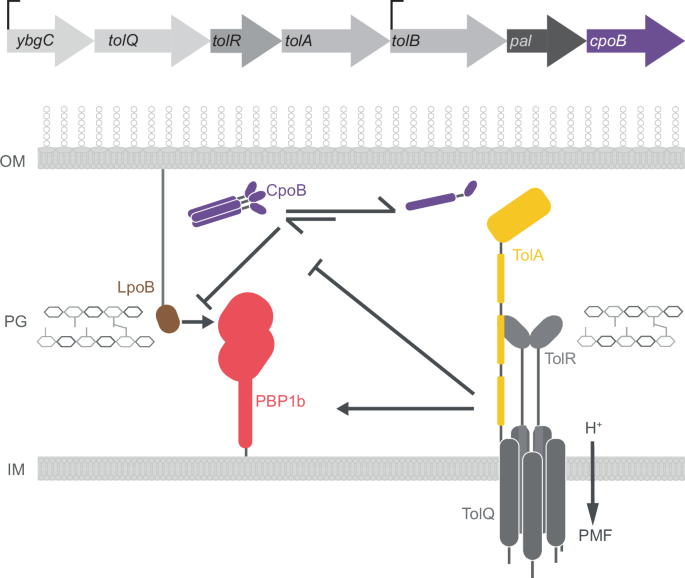

The persistence of Gram-negative bacteria inherently relies on maintenance of envelope integrity. Particularly during cell division where the envelope encounters increased force as it invaginates and separates. The Tol-Pal system plays an essential role in stabilisation of the envelope during division (discussed in detail in ref. 44). The tol-pal operon encodes seven proteins, with five including, TolQ, TolR, TolA, TolB, and Pal (Fig. 1B) being critical for function (Reviewed in ref. 45) and highly conserved across Gram-negative bacteria34,46,47. Deletion of core tol-pal gene/s results in defective membrane invagination, cell blebbing, increased release of OM vesicles, heightened sensitivity to detergents and drugs such as polymyxins, activation of cell stress responses, and alterations in LPS composition (Fig. 2)48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56. This review highlights the role of the Tol-Pal system in envelope stability and connectivity during division, that extends beyond mere stabilisation of the OM. Whilst much remains to be discovered about how Gram-negative bacteria coordinate the growth of cell envelope layers to ensure cell vitality, recent evidence points to the Tol-Pal system being a major player in this process. This makes the Tol-Pal system a novel target for the development of envelope destabilising drugs to combat the growing antibiotic resistance crisis.

Loss of Tol-Pal function results in pleiotropic phenotype resulting in lowered pathogen burden, heightened antibiotic sensitivity, and accelerated removal of bacteria by the immune system.

The contribution of outer membrane stability to envelope durability

It was long believed that the PG was the primary structural component of the bacterial envelope, providing resistance to mechanical stresses such as turgor pressure57,58. However, recent studies demonstrated the OM also contributes to envelope integrity59,60,61,62. Here, the unique proteolipid composition of the OM creates a robust network of interactions across the cell surface that is crucial for ensuring membrane stiffness and the rod shape of E. coli63,64. Perturbation in OM structure through increased LPS synthesis leads to enhanced envelope deformation, particularly during stretching and bending63. Similarly, alterations in OM composition can compensate for defects in the PG synthesis machinery, rescuing growth and shape64. These findings support a new dogma where cooperativity between the OM and PG of Gram-negative bacteria is essential for preserving the mechanical integrity of the entire cell envelope65. This phenomenon is further exemplified in A. baumannii. Here the loss of cell viability that is associated with lipooligosaccharide (LOS) deficiency in the OM, required a reduced amount or the absence of the PG synthase, penicillin binding protein (PBP) 1A66,67. This suggests that the interplay between the OM and PG layers is conserved across many Gram-negative bacteria. Although cooperativity between the OM and PG could provide a protective advantage by compensating for the loss of system function, A. baumannii with a defective Tol-Pal system still exhibits defects in cell shape and growth68. This reiterates the essential role of Tol-Pal system in maintaining envelope stability during cell division43,69.

The Tol-Pal system stabilises the OM by increasing the number of linkages to the underlying PG, via the lipoprotein Pal (Fig. 1A). Similarly, static links between OM and PG such as those afforded by Lpp and OmpA, have been shown to modulate the mechanical strength of the envelope and their loss leads to increased susceptibility to antibiotics32. The interactions between the OM and PG must be regulated (Fig. 1B) in response to the cell growth, with increased strain and mechanical force experienced as cells septate. For some lipoproteins, production is regulated in response to cell need. One such example is SlyB where expression is induced by the stress response accompanying loss of OM asymmetry70. In the case of lipoprotein Lpp, its tethering is regulated by the amidase, DpaA, which releases Lpp from the PG32,71,72,73,74,75. For Pal, it is the role of the remaining four core Tol-Pal system proteins to redirect Pal to the septum in dividing cells43. When this system fails destabilisation of the OM and alterations in PG composition occur44.

Connections between the OM and PG also serve as platforms for interactions with cytoplasmic membrane proteins, as is exemplified by the Tol-Pal system. In non-dividing cells, Pal is distributed around the periphery. As the cell begins to divide TolB diffuses within the periplasm, binds to Pal, disrupting its interaction with the PG and facilitating diffusion of the TolB-Pal complex towards the division site. The removal of TolB and subsequent deposition of Pal, requires the periplasmic effector protein, TolA43,45. TolA, through a single transmembrane helix (TolA I), associates with the motor complex of TolQ:TolR embedded within the cytoplasmic membrane45,76. The formation of this envelope-spanning complex is essential for converting energy from the PMF into torque, enabling the stripping of TolB from Pal45. Hence, the Tol-Pal system illustrates how cell envelope stability relies on the connectivity between all its three layers.

Mechanisms of envelope connectivity during cell proliferation

Classically, synthesis of the OM and PG have been studied independently. However, evidence increasingly supports a synergy between the two layers. Here multiprotein complexes involved in processes such as OMP insertion, sporulation, elongation, and division, are regulated through interactions with other envelope-localised molecules. The Tol-Pal system exemplifies this interconnection, whereby OM stabilisation is dependent on the presence of a functional PG binding domain in OM bound lipoprotein Pal, and the PMF-dependent assembly of the operative complex69. Emerging research has revealed that the Tol-Pal system also interacts with lipoprotein NlpD and closely related DipM. NlpD, which contains a LytM domain, necessary for amidase activation and PG remodelling, requires an energised Tol-Pal system for activation77. It was proposed that the function of Tol-Pal is to bring NlpD closer to the PG, thus allowing it to interact with amidases. However, the role of the Tol-Pal system in modulating PG synthesis via DipM remains to be established. In Caulobacter crescentus, the loss of the LtyM domain of the DipM endopeptidase results in OM blebbing and cell shape defects, like those observed for tol-pal mutants. These findings highlight the Tol-Pal system as critical for ensuring connectivity between the OM and PG, protecting against envelope instability associated with the tol phenotype78.

In addition to blebbing and shape defects, mutations in the Tol-Pal system frequently result in cell chaining79,80,81,82,83. This observation suggests that Tol-Pal has a specialised function in stabilising the OM at the division site to promote envelope constriction43,69. Intriguingly, recent research has uncovered that the chaining phenotype in tol-pal mutants is due to incomplete cleavage of the PG at the division site, underscoring the necessity of coordination between the OM and PG84. Although it is evident that the Tol-Pal system is crucial for efficient PG cleavage, the specific protein-protein interactions, and regulatory mechanisms involved remain to be elucidated. Remarkably, efficient division in the absence of a functional Tol-Pal system can be rescued by the over expression of glycan-cleaving lipoproteins84. This redundancy highlights the evolutionary importance of maintaining cell integrity, with bacteria developing multiple mechanisms to ensure envelope stability. Indeed, a recent study demonstrated that when the core PG insertion machinery is inhibited, PG cleaving enzymes can still maintain cell shape during elongation85. To achieve a comprehensive mechanistic understanding, further molecular details on the interactions and regulation of these systems is required.

While the Tol-Pal system is a major contributor to envelope connectivity, further interactions between envelope layers are also critical for envelope biogenesis. In E. coli, a network of OMPs decorate the cell surface and afford functionality to the envelope. The turnover of OMPs is essential for allowing bacteria to adapt to environmental changes. It was discovered that the insertion of OMPs via the Bam machinery is influenced by the composition of the underlying PG86. The reliance of OMP-insertion on the maturation state of PG enables cells to respond to both environmental conditions and growth requirements simultaneously19. Indeed in P. aeruginosa, it was shown that LpxC, a committed enzyme in LPS synthesis, is regulated by MurA, an enzyme dedicated to PG synthesis87. This demonstrates that biogenesis of the OM is intimately linked with the underlying PG, illustrating that bacteria have highly regulated mechanisms for coordinated formation of the cell envelope. Systems like the Tol-Pal complex, which interact with proteins across multiple layers, seemingly could have a role in indirectly regulating envelope biogenesis via these mechanisms88.

The role of envelope proteins in directing Tol-Pal to the septum

Proteins embedded within the cytoplasmic or outer membrane, or located in the periplasmic space, henceforth referred to as envelope proteins, constitute approximately one-third of the E. coli proteome89,90,91,92. These proteins form an extensive network of potential interactions and regulatory pathways. Numerous interactions have been identified between the protein machinery involved in elongation and division, and proteins in the OM, periplasm, and cytoskeleton93. Given the multifarious roles of the Tol-Pal system, it is not unexpected that this multi-protein complex serves as a scaffold, interacting with various envelope proteins. These transient interactions must be tightly controlled to meet cellular demands. One mechanism for achieving this is through the spatial and temporal localisation of Tol-Pal proteins during the cell cycle.

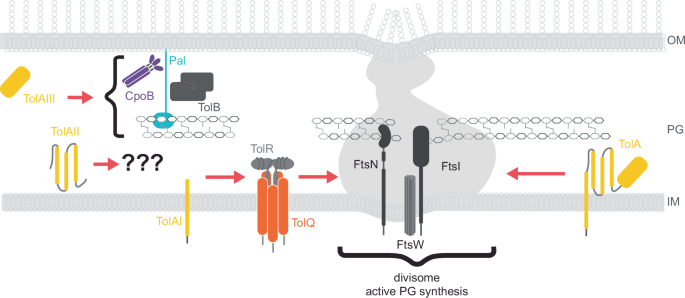

To ensure the OM is stabilised and remains connected to the PG during division, core Tol-Pal proteins are recruited to septa in pre-divisional cells. Recruitment of Pal to the septum requires the functionality of all five core Tol-Pal proteins69. Initially, TolB binds and mobilises Pal, and once at the septum, TolQ, TolR, and TolA are required to strip TolB from Pal43,45,69. Of the core Tol-Pal proteins, only TolA and TolQ are capable of independent redistribution to the septum (Fig. 3)83. The single transmembrane helix (TolA I) anchoring TolA in the cytoplasmic membrane can diffuse, and when associated with TolA domains II-III, localises to the division site (Fig. 3)83,94,95. TolA I alone is recruited to the divisome although unlike intact TolA retention becomes reliant on TolQ96,97. The periplasmic domain of TolA (TolA II) is also recruited to the septum and does so in the absence of TolA I or other Tol-Pal proteins (Fig. 3). This indicates that while TolA II does not require other Tol proteins for septal recruitment, interaction with other host factors is necessary96,97.

TolA and TolQ are recruited to the divisome separately, however both require FtsN and the presence of FtsI-driven PG synthesis for transport. Whilst TolA is generally intact within cells, it has been shown that TolA domains I, II, and III can be recruited to the divisome independent of each other. TolAI requires TolQ for recruitment, TolAII trafficking is facilitated by an unknown envelope partner/s, and TolAIII requires a combination of Tol-Pal proteins including CpoB, TolB, and Pal.

We speculate that, like TolA94, TolQ diffuses to the septum, in a process triggered by accessory proteins. In such a model, accessory proteins that are destined for the divisome, such as FstN83, associate with periplasmic regions of Tol-Pal proteins. This directs lateral movement through the fluid cytoplasmic membrane to the division site, via a mechanism similar to that observed for rhomboid proteases and the twin-arginine translocation system98,99. The localisation of dimeric TolR within the pentameric pore of TolQ76, explains the dependence of TolR on TolQ for trafficking to the septum. TolA can also aid TolR recruitment to the septum, although the biological relevance of TolA-TolR recruitment remains unclear76. Currently, no molecular mechanism for the interaction between TolR and TolA has been identified, However, in the homologous Ton system, the components ExbD and TonB, interact through a beta-strand motif within TonB domain II100. The prediction of a similar beta-strand within the analogous region of TolA II suggests that TolA and TolR may interact via a similar mechanism. The interconnectivity and functional redundancy in recruitment of Tol-Pal proteins to the division site highlight the internal spatial regulation of this system (Fig. 3).

The recruitment of TolQ and TolA to the division site via other proteins involved in envelope biogenesis introduces an additional layer of temporal regulation. One of the key proteins directing TolQ and TolA is FtsN, which associates with FtsWI at the divisome to ensure septal PG synthesis101. Indirect interactions between FtsN and TolQ/TolA facilitate their recruitment through piggybacking on FtsN divisome localisation (Fig. 3)97. Indeed the overexpression of TolQ, typically detrimental to cell fitness, can be mitigated by the concurrent overexpression of FtsN. This suggests a coordinated role for the septal recruitment of TolQ and sequestering of FtsN to align OM stabilisation with septal PG synthesis during division. Treatment with the beta-lactam aztreonam, which inhibits PG transpeptidase FstI, interferes with Tol-protein recruitment suggesting that FtsN stimulated PG synthesis is essential for spatial regulation of Tol-Pal97.

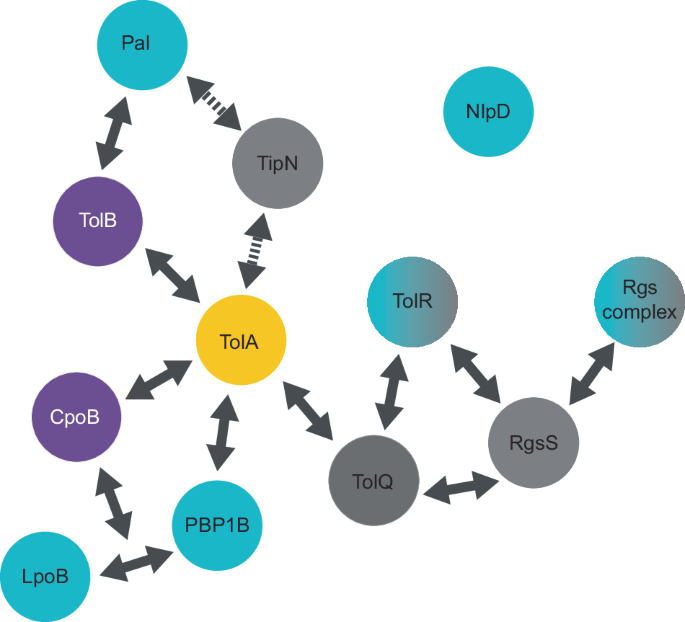

Further spatial regulation of Tol-Pal proteins has been observed in Caulobacter sp. where the cell pole marker protein TipN is maintained by interactions with TolA and Pal (Fig. 4). The recruitment of TipN to the new pole is essential for establishing the polarity axis in progeny cells, thereby preventing defects such as protein and organelle mislocalisation102. Additionally, interaction between TolA and Pal with TipN indirectly influences the positioning of the histidine kinase, PleC, which is essential for regulating polar differentiation103. This coordination is further exemplified by the interaction of TolQ and Pal with polar growth factors, specifically rhizobial growth and septation (Rgs) proteins. In Sinorhizobium meliloti, Rgs proteins localise with TolQ and Pal, directing them to the growing cell pole during elongation and to the septum in pre-divisional cells104. Notably, one such Rgs protein, RgsS, is a putative FtsN-like protein, suggesting that spatial and temporal regulation of the Tol-Pal system by the divisome and elongasome are likely conserved functions. The association of Tol-Pal proteins with systems that prevent division defects highlights the sophisticated mechanisms coordinating the temporal regulation of cell division proteins in bacterial cells.

Confirmed protein-protein interactions of the Tol-Pal system with division-related proteins are indicated by arrows. Dashed arrows represent interactions that have not been shown to be direct. Interactions involved in Tol-Pal regulation of PG synthesis are shown in blue, interactions with cytoplasmic membrane proteins are in grey, and periplasmic interactions are in purple. TolA (yellow) remains the central regulator of many interactions for both PG synthesis and division. How NlpD interacts with the system is yet to be understood.

Auxiliary Tol-Pal protein induced regulation of PG synthesis

Recruitment of Tol-Pal proteins to the septum facilitates regulation of PG synthesis through interactions with PG synthases (Figs. 4 and 5). PG synthase activity is tightly regulated across the envelope by protein complexes localised to the cytoplasmic membrane, such as the elongasome and divisome and by cytoskeletal proteins and lipoproteins that are associated with the OM20,105,106,107. In E. coli, it has been demonstrated that the activity of one of the major bifunctional PG synthases, PBP1B, is modulated by Tol-Pal proteins, TolA and CpoB (Figs. 4 and 5)108,109. CpoB, an accessory protein encoded within the Tol-Pal operon (Fig. 5), does not exhibit the classical Tol-Pal phenotype when deleted indicating its role is likely regulatory rather than structural43,46. CpoB interacts with PBP1B when bound to its lipoprotein activator, LpoB. This inhibits the hyper-activation of the transpeptidase domain. In contrast, TolA interacts with PBP1B to enhance synthase activity108. Beyond the direct modulation of PG synthase activity, the Tol-Pal system may also contribute to the spatial regulation of PG synthesis. The interactions between the envelope-spanning Tol-Pal system with PBPs and associated lipoprotein activators, might facilitate localisation of the PG synthase to breaks within the PG, thus aiding directed divisome and elongasome assembly110.

The Tol-Pal operon encoding seven proteins is shown with CpoB, the last protein in the sequence highlighted in purple. TolA and CpoB both modulate the activity of PBP1B, an auxiliary PG synthetase in the septum of dividing cells. Both the lipoprotein, LpoB, and TolA increase PBP1B activity, while CpoB inhibits LpoB-driven hyperactivation. Whilst TolA modulates CpoB oligomeric state, it is not known which state CpoB adopts when interacting with LpoB-PBP1B.

CpoB may act as a master regulator beyond its direct inhibition of PBP1B since it also interacts with TolA111. Although the biological role of the TolA-CpoB interaction is not fully understood, functional studies show that TolA modulates the oligomeric status of CpoB, leading to dissociation of CpoB trimers into monomers (Fig. 5). Additionally, CpoB in combination with TolB and Pal is necessary for localisation of the C-terminal domain of TolA (TolA III) to the septum (Fig. 3)97. Thus, it is possible that the oligomeric state of CpoB influences its choice of and affinity for binding partners. This would allow for fine-tuned regulation of the interactions between CpoB, PBP1B, and other Tol-Pal proteins (Fig. 5). By modulating the affinity of Tol-Pal proteins with other envelope proteins in this way CpoB could facilitate precise control over complex formation and regulation in response to cell cycle as well as the local binding partner distribution. Integrating CpoB as a regulatory component into this intricate network governing PG synthesis and cell division builds a bigger picture for Tol-Pal-directed coordination of envelope biogenesis.

The Tol-Pal system as a novel target for antibiotic development

Concomitant with their discovery as factors granting cells “tolerance” to colicins, tol mutants were described as sensitive to EDTA, sodium deoxycholate, and a series of dyes52,112,113,114. Even though it was counterintuitive at the time, it was suggested that these genes are important for the stability of the cell envelope. Over the years the Tol-Pal system has been implicated in variety of functions from OM lipid balance to nutrient transport, all involving homeostasis of the bacterial envelope (Fig. 2)55,56,115,116. Related to these roles, the loss of the Tol-Pal system sensitises cells to numerous detergents and antibiotics, like polymyxin B, tetracycline, novobiocin, vancomycin, chloramphenicol, and a large variety of beta-lactam antibiotics53,117,118,119,120. While it should be noted that variation exists in the antibiotic sensitivity amongst species and strains, due to differences in their envelope structure and composition and lack of standardisation in methods used in the studies, general increased sensitivity to beta-lactams seems to be constant across species68,79,117. From the beginning, the tol phenotype was connected to leakage of periplasmic contents. This led to a belief that in tol deletions the OM is highly permeable and allows for an influx of higher concentrations of compounds. However, the basis of tol-associated drug sensitivity may be more complex than simple loss of the OM stability, concomitant with the many roles this system has in cell envelope stability.

Whilst OM permeability is increased in tol mutants, there was no corresponding increase in the level of beta-lactam antibiotics bound to PBPs110,117. This makes involvement of the Tol-Pal system in PG remodelling of particular interest for antibiotic development. In antibiotic screens, tol mutants are sensitive to beta-lactams targeting both the elongasome and divisome machinery, however the effect on the elongasome seems to be modest in comparison110,120. This is consistent with Tol-Pal’s major role being connected to cell division43,48,83,84,119,121,122. Cell division is an intricate process involving 50+ proteins, tightly spatiotemporally regulated. At the septum, PG is synthesised by two complexes, FtsIW which forms a leading edge, and PBP1B-LpoB which is thought to backfill and reinforce the division site123. Treatment of tol mutants with antibiotics, like aztreonam or cephalexin which target cell division-associated PG synthases, leads to increased cell lysis. Of particular interest is aztreonam which in combination with avibactam has proved to be particularly effective against metallo-β-lactamase producing Gram-negative bacteria124,125,126. The combination developed by Pfizer under the name EMBLAVEO was approved by the European Commission for use against serious infections caused by the Gram-negative bacteria in April 2024.

Increased sensitivity of tol-pal mutants to divisome affecting antibiotics appears to stem from the loss of control over PBP1B activity. Aztreonam does not affect PBP1B localisation to the septum nor its interactions with PBP3/FtsI127. However, LpoB recruitment to the septum is diminished, decreasing the activity of PBP1B108,109,127. The loss of energised action by TolA would further alter PBP1B activity, directly, or indirectly by loss of CpoB regulation. However, the molecular details of how Tol-Pal provides resistance against beta-lactam antibiotics is still not well understood.

Interestingly, cell lysis following treatment with PG synthase-targeting antibiotics is reduced by overexpression of the cell division inhibitor, SulA110. This inter-layer coordination is further observed in tolA or pal mutants where growth defects are aggravated in cells that also lack cell division machinery, lipoprotein lpoB or PBP1B108,110. It was suggested that the loss of the PBP1B-LpoB interaction is akin to losing the OM-PG linkage that is supported by Tol-Pal. In such an interconnected system cell viability persists despite the failure of one subsystem, as the remaining operational subsystem can assume the stabilisation function. However, the failure of two subsystems results in a significant collapse of the OM. This compensation is also observed when Pal accumulation at the septum is lost but can be substituted for by Lpp enrichment128. Similarly, widening of periplasmic space by increasing the length of Lpp is permissible only if all other OM-PG links are intact, including PBP1A-LpoA and PBP1B-LpoB pairs129. More complex mechanisms start to emerge with discovery of regulatory roles for TolA and CpoB in PG synthesis and with the advent of studies trying to understand mechanistic details of antibiotics targeting these systems.

Despite our limited understanding of the molecular mechanisms driving tol-pal associated antibiotic sensitivity, the system makes for an attractive drug target. Loss of Tol-Pal function not only increases permeability to compounds that are normally excluded by the OM but would also allow for decreased dosage of last resort antibiotics like polymyxin B. Tol-Pal system mutants, which exhibit diminished pathogen virulence, have further potential as vaccine candidates. This potential extends to mutant Tol-Pal proteins and outer membrane vesicles produced by mutant strains (discussed in detail in ref. 130).

Concluding insights

The construction and maintenance of the cell envelope in Gram-negative bacteria is critical for survival and replication. Emerging evidence highlights that the essential coordination between the different layers of the cell envelope contributes to the pathogenicity of these bacteria65. To this end this review focused on the role of the Tol-Pal system in ensuring the stability of the OM and its linkage to overall envelope integrity. The Tol-Pal system comprises several proteins that are guided to the septa in dividing cells by divisome proteins. This interaction provides spatial and temporal regulation of Tol-Pal-mediated envelope stabilisation. Although many specific interactions responsible for the recruitment of individual Tol proteins have been identified (Fig. 3), the collaborative function of these envelope proteins within the crowded cellular environment remains unclear. Additionally, it is yet to be determined whether the Tol-Pal system i) continues to interact with the divisome once at the division site and ii) influences divisome protein composition.

New insights into the key role of the Tol-Pal system in facilitating envelope connectivity and regulating PG synthesis suggest that interactions with elongasome components also warrant further investigation. Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing interactions of the Tol-Pal system with divisome and elongasome proteins is essential for targeting these interactions for antibiotic development. The role of the Tol-Pal system in regulating PG synthesis presents a promising avenue for enhancing the efficacy of current antibiotics, such as beta-lactams, which target PG synthesis machinery. However, the complex interplay between the Tol-Pal system and envelope machinery is challenging to unravel due to functional redundancy and subsystem compensation for loss of function.

The mechanisms underlying the reduced fitness associated with Tol-defective cells are not fully understood. A deeper understanding of the roles for each Tol-Pal component in generation of the Tol-Pal phenotype is necessary to exploit this system as an antimicrobial target. Specifically, the mechanisms behind distinctive blebbing, cell chaining, and outer membrane vesicle production resulting from system malfunction require elucidation. We propose that targeting TolA is a promising route because it acts as a hub for interactions with other envelope proteins (Fig. 4). Moreover, the relationship between increased outer membrane permeability due to Tol-Pal dysfunction and antibiotic effectiveness requires further investigation to understand why increased permeability does not always correlate with higher antibiotic binding to PG targets.

Overall, the role of the Tol-Pal system extends beyond OM maintenance, safeguarding connectivity between the three layers of the Gram-negative cell envelope.

Responses