Microbial solutions must be deployed against climate catastrophe

Microbes and the climate crisis

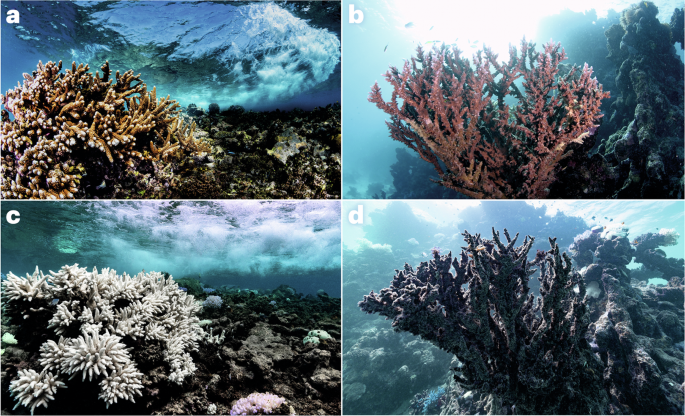

Microorganisms have a pivotal but often overlooked role in the climate system1,2,3 — they drive the biogeochemical cycles of our planet, are responsible for the emission, capture and transformation of greenhouse gases, and control the fate of carbon in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. From humans to corals, most organisms rely on a microbiome that assists with nutrient acquisition, defence against pathogens and other functions. Climate change can shift this host–microbiome relationship from beneficial to harmful4. For example, ongoing global coral bleaching events, where symbiotic host–microbiome relationships are replaced by dysbiotic (that is, pathogenic) interactions (Fig. 1), and the consequent mass mortality mean the extinction of these ‘rainforests of the sea’ may be witnessed in this lifetime5. Specifically, a decline of 70–90% in coral reefs is expected with a global temperature rise of 1.5 °C (ref. 6). Although this example highlights how the microbiome is inextricably linked to climate problems, there is a wealth of evidence that microbes and the microbiome have untapped potential as viable climate solutions (Table 1). However, despite the promise of these approaches, they have yet to be embraced or deployed at scale in a safe and coordinated way that integrates the necessary but also feasible risk assessment and ethical considerations7.

a–d Examples of the same healthy (a, b), bleached (c) and dead (d) corals before (a, b) and after (c, d) being affected by heatwaves caused by climate change. Photos by Morgan Bennett-Smith.

Mobilizing microbiome solutions to climate change

The multifaceted impacts of climate change on the environment, health and global economy demand a similar, if not more urgent and broad, mobilization of technologies as observed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic8,9. To facilitate the use of microbiome-based approaches and drawing from lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic9, we advocate for a decentralized yet globally coordinated strategy that cuts through bureaucratic red tape and considers local cultural and societal regulations, culture, expertise and needs. We are ready to work across sectors to deploy microbiome technologies at scale in the field.

We also propose that a global science-based climate task force comprising representatives from scientific societies and institutions should be formed to facilitate the deployment of these microbiome technologies. We volunteer ourselves to spearhead this, but we need your help too. Such a task force would provide stakeholders such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) committee and United Nations COP conference organizers, and global governments access to rigorous, rapid response solutions. Accompanied by an evidence-based framework, the task force will enable pilot tests to validate and scale up solutions, apply for dedicated funding, facilitate cross-sector collaboration and streamlined regulatory processes while ensuring rigorous safety and risk assessments. The effectiveness of this framework will be evaluated by key performance indicators, assessing the scope and impact of mitigation strategies on carbon reduction, ecosystem restoration and enhancement of resilience in affected communities, aiming to provide a diverse and adaptable response to the urgent climate challenges faced today. We must ensure that science is at the forefront of the global response to the climate crisis.

We encourage all relevant initiatives, governments and stakeholders to reach out to us at [email protected]. We are ready and willing to use our expertise, data, time and support for immediate action.

Responses