The Biodiversity Credit Market needs rigorous baseline, monitoring, and validation practices

Introduction

Globally, biodiversity faces significant threats1 and efforts to protect and conserve it are critically underfunded2. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework adopted at COP15 in December 2022 stimulated activity around biodiversity financing, including the possibility of a Biodiversity Credit Market (BCM)3. The BCM could offer a novel solution for incentivizing the conservation and restoration of natural habitats through a voluntary trading system of credits, but discussions of this nascent market overwhelmingly focus on regulatory frameworks and market demand4. A robust regulatory framework is necessary to prevent issues like double counting and other potential abuses that undermine credibility. Equally important is the willingness of businesses and governments to purchase biodiversity credits. Unfortunately, much less attention has been given to biodiversity in the Biodiversity Credit Market. This initiative could benefit biodiversity, but each project’s claims must be credible, and implementing cutting-edge biodiversity science in the project design and monitoring phases is paramount.

Although the BCM could enhance conservation funding, currently it shares similarities with existing carbon credit and biodiversity offset markets, and these initiatives have faced challenges such as inaccurate baselines, inadequate monitoring, and transparency issues5. To avoid these pitfalls, I describe three strategies to enhance the effectiveness of the BCM: 1) accurately define the project’s baseline by including control sites to ensure projects demonstrate additionality and permanence and contribute genuine long-term biodiversity benefits, 2) implement a robust monitoring strategy that encompasses a significant spectrum of regional biodiversity to provide a comprehensive impact assessment, and 3) establish a transparent and economically feasible verification process for project claims, enhancing accountability and trust (Table 1). These changes are essential for the BCM to successfully contribute to global biodiversity conservation.

Calculating a biodiversity baseline for conservation and restoration projects can be tricky

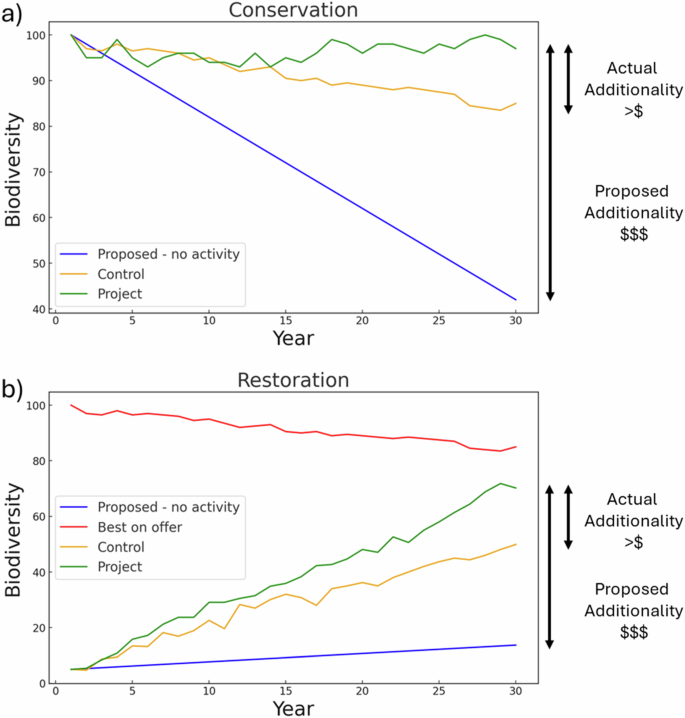

The purpose of the baseline is to define what would be the long-term trajectory of biodiversity if no new action is taken (Fig. 1). This is necessary to determine the additionality or the net positive impact of a project. In other words, how have a project’s activities increased biodiversity above a counterfactual of no activity6?

a In a conservation project, the one-time projected baseline predicts an approximate loss of 60% of the biodiversity in 30 years due to deforestation, and thus claims a large additionality by protecting a threatened area. But if a control, properly matched to the drivers of change in the project, had been monitored where no conservation actions were taken (i.e. counterfactual) and there was much less deforestation and loss of biodiversity, the project should claim much less additionality. b In a restoration project, the one-time projected baseline predicts a small increase in biodiversity recovery (proposed – no activity) during the first 30 years of the project, and thus claims large additionality because the restoration activities of the project (project) greatly increased forest cover and biodiversity. But if a well-matched control had been monitored where no restoration actions was taken (i.e. counterfactual), they would have documented significant biodiversity recovery due to secondary succession, thus greatly reducing the actual additionality that could be claimed by the project. The trajectory of the Best on offer (i.e. intact reference site) is included as a reference for deciding the proportion of biodiversity recovery.

Historically, carbon offset projects often proposed baselines that overestimate future gains, undermining the credibility of their additionality claims5. For instance, forest conservation projects might predict high rates of future deforestation to amplify the perceived impact of their conservation efforts, awarding them carbon credits for carbon that deforestation would have released. These baseline predictions (i.e. ex ante) are seldom validated or adjusted during the life of a project, resulting in credits being allocated when they should not5. Similarly, forest restoration projects might overstate their impact by setting a low baseline of no natural recovery, disregarding the potential for natural regeneration. During the first 20 years of secondary succession, biomass recovery in tropical ecosystems can increase by ~5 mg/ha/yr7. If a project does not include adequate monitoring of counterfactuals, then a substantial portion of forest recovery, hence carbon sequestration, may occur independently of the project’ activities, suggesting that fewer credits should be allocated (Fig. 1).

The failures in establishing accurate baselines for carbon sequestration projects highlight potential difficulties in setting reliable baselines for biodiversity projects. Biodiversity’s complexity, with its diverse components and definitions, poses greater challenges compared to the relatively well-documented carbon cycle. Even if we simplify this task by excluding bacteria, virus, fungi, and genetic variation within a species and focus solely on “observable biodiversity” (e.g. plants, vertebrates, and invertebrates), the population dynamics of fauna can still fluctuate dramatically, even in well-protected sites8. A major driver of these fluctuations is variation in weather patterns (e.g., El Niño Southern Oscillation)9, and this variability is rarely incorporated in a project baseline. Instead of relying on a static theoretical baseline, the BCM should monitor control sites in both degraded and relatively pristine habitats (i.e., best-on-offer) that are well-matched with the project site10,11 to establish dynamic baselines that accurately reflect the responses of biodiversity to ecological changes, climate fluctuations, and anthropogenic impacts.

For example, if a BCM conservation project assumes that an intact forest will be deforested by 60% during the next 30 years (Fig. 1a), at a minimum the land use patterns in adjacent properties and the region should be monitored, to ensure that there was no leakage effect (e.g. logging and biodiversity loss is halted in the project area, but these activities shift to another area). An important challenge for documenting leakage is determining at what spatial and temporal scales monitoring should be implemented.

Similarly, controls or counterfactuals should be monitored in restoration projects, because just as biomass can recover rapidly during secondary succession, so can fauna12. Furthermore, while conservation activities generally increase the biodiversity of a site, this is not always the case6, but if controls are not established and monitored at the same intensity of the project site it is impossible to determine if a BCM project has had a desired net positive impact. Finally, to ensure the longevity of conservation benefits, it is essential that biodiversity credit standards incorporate permanence, requiring projects to last for at least 30 to 50 years, if not longer.

What biodiversity should be monitored?

The unit of measure for credit in the carbon market is one metric ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e), which represents greenhouse gases that have been removed from the atmosphere or prevented from being emitted. In contrast, defining a single unit of measure for the Biodiversity Credit Market (BCM) is challenging due to the multifaceted nature of biodiversity. If the primary goal of the BCM is to incentivize the preservation and restoration of biodiversity, then the components of biodiversity monitored, as well as the monitoring techniques and sampling designs should capture the complexity of ecosystems by monitoring habitats, and the population dynamics of the flora and fauna.

Habitat diversity or the presence of unique or threatened habitats has been the biodiversity measures used by some of the initial BCM projects. For example, in the UK, habitat, hedgerows, and watercourses are used as a proxy for biodiversity13. An advantage of this approach is that monitoring and validation can often be carried out with aerial imagery (e.g. satellites or drones) reducing costs. A disadvantage of this approach is that there is no direct measure of individual species, which are a major component of biodiversity. This is concerning due to the well-documented “empty forest” phenomenon, where habitat or forest cover does not necessarily indicate the presence of healthy flora and fauna communities within14,15. Since the objective of the BCM is to benefit biodiversity, measures of individual species, specifically the trajectories of population dynamics, must be included in the baseline and monitoring components of all BCM projects.

Measuring the change in habitat is an important component, but it is not sufficient. Today, it is not unreasonable to monitor multiple species of plants and animals, along with habitat cover and land use change. The tools for monitoring multiple components of biodiversity continue to improve, providing an opportunity to use cutting-edge science to accurately document the impacts of each BCM project.

Aerial imagery from satellites and drones can provide detailed information about habitat cover and land use change and they can also provide detailed information of vegetation parameters16. For example, LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology can provide detailed three-dimensional information about forest structure, tree height, and forest biomass, and hyperspectral imagery captures detailed spectral signatures that can be used to identify plant species. Furthermore, drone technology along with AI identification algorithms promise to reduce the costs of monitoring forest species composition, even in tropical forests, to as low as US$1/ha17.

In terms of monitoring the biodiversity of the fauna, a large proportion can be captured using a combination of camera traps, acoustic monitoring, and environmental DNA (eDNA). Camera traps provide non-invasive means of monitoring the presence and population trends of terrestrial mammals and large ground birds18,19. Passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) compliments camera traps by monitoring vocalizing species, which include birds, amphibians, insects, and arboreal mammals (e.g. primates)20. Environmental DNA can corroborate the results of camera traps and PAM and include a wide range of aquatic and terrestrial vertebrates, invertebrates, and microorganisms, making it a versatile tool for assessing biodiversity across a diversity of ecosystems21. The advantage of these methodologies is that much of data collection, analyses, and presentation of the results can be automated with the assistance of artificial intelligence algorithms22, thereby reducing costs, and increasing transparency if all data, analyses, and trends are made publicly available.

How should project claims be validated?

An independent third party must verify a project’s biodiversity conservation or enhancement claims. In theory, this should reduce exaggerated claims, but unfortunately, this has not been the case in the carbon market5. Presently, each project contracts the verification party, which could lead to a conflict of interest. One solution would be for a verification panel to be part of a new regional or country-level institution responsible for the initial project approval, certification, and credit registry. The roles of these institutions would be: (1) determine the minimum biodiversity measures required for the project, (2) determine the appropriate monitoring design and methodology, (3) define the minimum area and time (i.e. permanence) of a project, (4) define the conditions that are needed to determine additionality and the assigning of biodiversity credits, (5) provide a project oversight and verification panel consisting of biodiversity experts to advise during the project and review the annual reports, and (6) insure transparency by making all project information, data, reports, and evaluations publicly available on an immutable blockchain ledger.

The verification process should still be paid for by each project, possibly based on the size and complexity of the project, but the standards and crediting institution would assign the verification panel. The evaluation process should be rules-based to reduce bias in decision-making and assure consistency and transparency. For example, in a restoration project, the aggregate biodiversity measure of a project would be compared with a degraded habitat baseline to determine the net positive gains or additionality. The additionality would then be compared with the best-on-offer biodiversity to calculate the proportion of biodiversity enhancement23 and the number of credits that should be allocated. Furthermore, the process should be scalable to evaluate many projects relatively cheaply so that other regions or countries could adopt it with minor modifications.

Let’s get it right

During the last 20 years, biodiversity monitoring has greatly improved due to advances in technology and artificial intelligence. We now can monitor components of biodiversity in real-time (e.g. acoustics) and others at the regional scale (e.g. land use change). eDNA provides an unprecedented capability for monitoring biodiversity, including elusive or rare species that were previously challenging to detect. These advances must be included in the protocols for documenting the impacts of BCM projects. However documenting change in biodiversity in the project site is not sufficient. All projects need to be compared to dynamic baselines based on counterfactuals sites (i.e. no action) and with best-on-offer sites within the region to ensure that the project has provided net positive gains in biodiversity. Additional monitoring will increase project costs, but it will also increase the credibility and reliability of the BCM. Furthermore, a truly independent evaluation procedure, along with publicly accessible documentation using a blockchain ledger can provide transparency.

The conservation of global biodiversity is at a pivotal moment. By adopting a unified global standard for the biodiversity credit market, we can create a clear, consistent framework that benefits all stakeholders. By integrating the latest advances in conservation science and establishing cohesive standards and protocols, we have the opportunity to attract private finance and make meaningful progress toward our urgent conservation goals.

Responses