Marine mammals as indicators of Anthropocene Ocean Health

Introduction

Few creatures capture the imagination and fascination of humans as do whales and dolphins (cetaceans). These animals can be used as good indicators of the health of our Ocean1,2 and Ocean Health, in turn, has implications for global health1. Evidence of the impacts of anthropogenic activities on whales and dolphins is increasing quickly and everywhere. Ocean noise from a variety of sources, such as shipping, oil and gas exploration, and recreational activities, has been documented as the number one pollution problem in the world’s Ocean today (refs. 3,4,5; Fig. 1). Other forms of pollution, such as plastic pollution, including microplastics6, marine debris7, pollutants originating from human and medical waste8,9, mining10, and those resulting from agricultural practices that end up in the Ocean via run-off11,12 are increasingly being documented to affect cetaceans. In addition, signs of disease13 and poor nutrition14 are becoming more prevalent as a result of habitat degradation and overfishing. Thus, global change includes not only anthropogenically driven climate change, but also increasing and unsustainable levels of pollution. However, our global Ocean is not only important for industry (as shipping highways, sources of fossil fuels and renewables), but its proper functioning is also paramount for food security and climate change mitigation. Thus it is clear that Ocean Health, as reflected by the health of whales and dolphins, is a key concern for our species’ survival on this planet.

One of the multiple areas of human-wildlife conflict in the Ocean:breaching humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) and ship. Photocredit: Brigitte Melly/Stephanie Plön.

Multiple, cumulative impacts on marine mammals

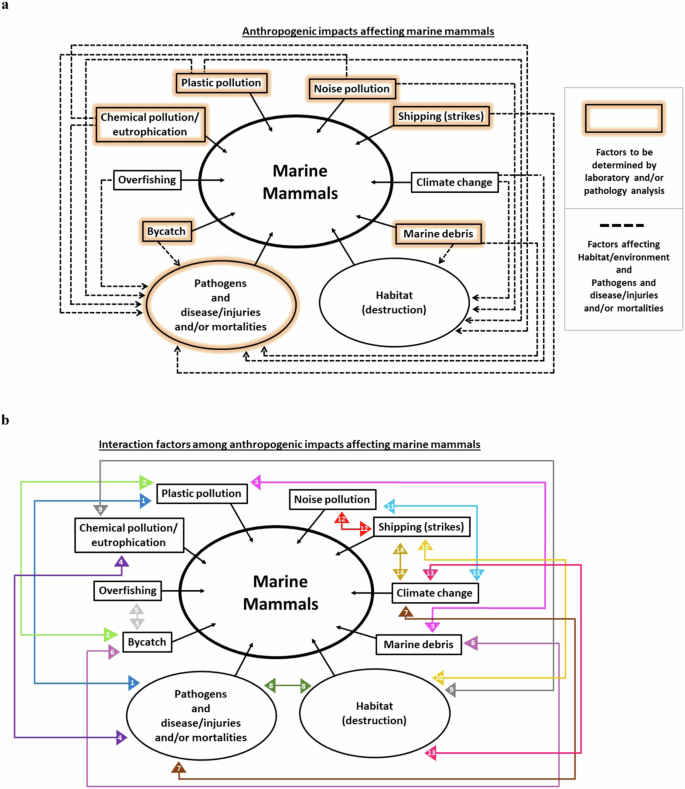

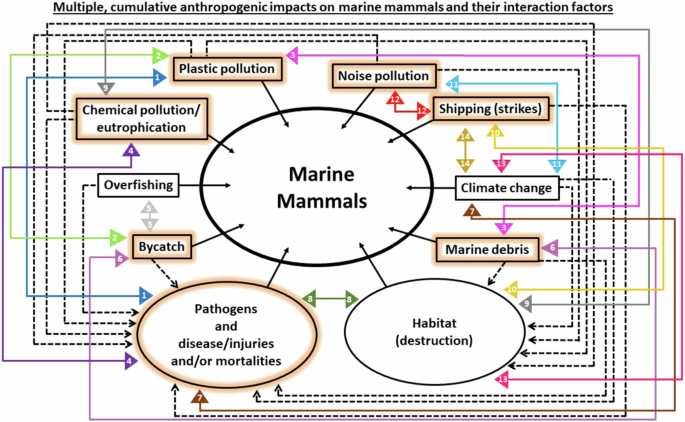

Anthropogenic impacts on marine mammals affect individuals and populations in two basic ways: either via an impact on the Ocean environment (environment/habitat) or via the overall health of individuals and populations (through pathogens & disease, injury and/or mortality) or both (Fig. 2a). Further interaction factors between the individual anthropogenic impacts may add to the overall impact (Fig. 2b). Thus, the overall health of the individual is an indicator of the effects of multiple stressors, and in turn effects on multiple individuals will influence the vital rates of the population, leading to population-level consequences15,16. Therefore, the health of an individual essentially reflects the cumulative effects of multiple stressors, and consequently, marine mammals can be viewed as indicators of the overall health of our Ocean2.

a shows the multitude of anthropogenic factors and b highlights their interaction factors, showing the overall complexity of the problem and highlighting its urgency. Orange boxes indicate impacts that require verification through laboratory analyses; dashed arrows show how the various anthropogenic factors impact either the habitat and/or the health of the animals. 1. Ingestion of plastic blocks the digestive tract, causing starvation123, and vulnerability to pathogens and disease. Microplastics accumulate in prey species, causing illness due to bacteria/viruses and pollutants124. 2. Plastic waste causes entanglements, leading to drag and resulting in higher energy expenditure and/or drowning and starvation, and physical trauma with amputation and infection125. 3. 40–80% of oceanic marine debris is made up of plastic126, affecting marine mammals in various ways (see 1 and 2 in the diagram). 4. Many chemical pollutants cause immunosuppression127, increasing susceptibility to pathogenic infections and diseases128,129,130. 5. Overfishing increases the probability of bycatch131 and results in a drop in population numbers132. 6. Marine debris leads to entanglement and entrapment133. 7. Climate change causes Ocean warming, resulting in new and dangerous pathogens & diseases, while intensifying the effects of present ones134, plus resulting in changed and/or lower prey availability, causing starvation and susceptibility to pathogens & disease130, and thus a decline in marine mammal populations135. 8. Decrease in available habitat causes populations/animals to cluster in smaller spaces, increasing the probability of pathogen and disease transfer135. 9. Agricultural chemicals contaminate rivers that flow into bays and estuaries, causing accumulation of toxins in coastal and near-shore species and eutrophication of coastal zones, with detrimental health effects12. 10. Increased shipping causes a decrease in marine mammal habitat and likely a higher probability of shipwrecks, further destroying habitat, for example, via resulting oil pollution136. 11. Melting Ocean ice cover increases available space for industrial activities, like shipping and oil drilling, increasing noise pollution in the Ocean137. 12. Increased shipping causes more Ocean noise, interfering with marine mammal hearing, communication, foraging and navigation4. 13. Climate change affects prey distribution and alters/destroys habitat130. 14. Increasing temperatures cause melting of polar ice caps, resulting in more shipping areas, particularly in the northern polar regions, increasing the likelihood of ship strikes138.

Multiple stressors can be additive, synergistic or antagonistic and predicting the effects of cumulative stressors is challenging due these interactions17, adding another level of complexity18. At present, there is a pressing need to quantify multiple, cumulative stressors on cetacean populations to inform policy about ‘allowable harm limits’19 or levels below ‘acceptable threshholds’20 to implement mitigation measures that alleviate these stressors21,22. Most of these multiple cumulative stressors coincide in coastal environments21 and marine mammal communities in enclosed seas, such as the Mediterranean, are particularly at risk as these areas show up as hotspots for almost all threat categories21. Cumulative effects disrupt ecological connectivity23, and the combined effects of multiple stressors can be amplified at the community level when stressors act on influential groups that act as ecosystem engineers18,20, such as cetaceans, having an effect on major Ocean ecosystems24.

Visualising the multiple, cumulative anthropogenic impacts (Fig. 2a) in combination with the various interaction factors (Fig. 2b) highlights the threat, complexity and urgency of this problem for the ongoing biodiversity crisis that also affects our Ocean (Fig. 3; ref. 25).

Combining Fig. 2a and b highlights the complexity of multiple, cumulative anthropogenic impacts and their interaction factors on marine mammals.

Cumulative impacts result in increasing complexity

Complexity, characterised by a high number and diversity of interacting components or elements26, arises in natural systems when multiple processes operate at different spatial and temporal scales-as is the case for Ocean systems and many of the processes within them (see Fig. 2). While research focused on single variables, such as increased sea surface temperature or an individual species (e.g. refs. 27,28), has contributed to our understanding of global change, such approaches often fail to address the otherwise complex nature of these systems and there is a risk that this may lead to overly conservative estimates of the scale and speed of onset of future impacts29.

Marine mammals as ‘indicators’

In this respect, marine mammals and other top marine predators (including certain species of predatory fish, seabirds and sea turtles) have been proposed as ecosystem sentinels based on their conspicuous nature and capacity to indicate or respond to changes in ecosystem structure and function that would otherwise be difficult to observe directly30,31. They are also often cited as sentinels for Ocean and human health, because they are long-lived, often feed at upper trophic levels, have fat stores that accumulate anthropogenic toxins, and are vulnerable to many of the same pathogens, toxins, and chemicals as humans30,32,33.

However, this original concept of marine mammals as ‘sentinels’ of Ocean Health32,34,35,36,37, providing an early warning of existing or emerging health hazards in the Ocean environment, is increasingly obsolete due to the rapid rate of disappearance of these ‘canaries of the mineshaft’2. Thus, we propose the use of the term ‘indicators’, highlighting the advanced state of change in the system in which they live. The indicator concept has been frequently associated with terrestrial systems, and indicator species are defined as those that can be used as ecological indicators of community types, habitat conditions, or environmental changes38,39,40. They are characterized by some or all of the following: (a) provide early warning of natural responses to environmental impacts41,42; (b) directly indicate the cause of change rather than simply the existence of change43; (c) provide continuous assessment over a wide range and intensity of stresses42; and (d) are cost-effective to measure and can be accurately estimated by all personnel (even non-specialists) involved in the monitoring44.

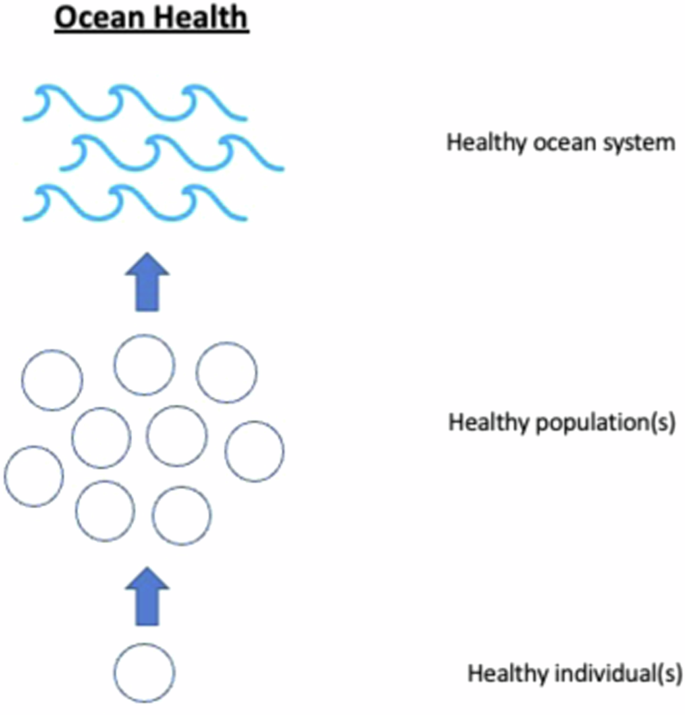

Marine mammals have the capacity to integrate and reflect complex ecosystem changes through their ecological and physiological responses45, thus making good indicators of changing Ocean conditions and overall Ocean Health2. The fact that we see rapidly deteriorating conditions in both individual and population health in marine mammals reflects the deteriorating conditions at lower trophic levels, indicative of ecosystem-level changes. Using marine mammals as indicators of Ocean Health reflects a more holistic approach to health, focusing on the individual as well as population-level health, including genetic diversity, population connectivity and size (ref. 2; Fig. 3). Recent publications have already started to adopt the concept of cetaceans as indicators of Ocean Health with respect to chemical pollution46 and marine litter47 (Fig. 4).

Scientists increasingly warn of an imperilled Ocean48 and the changes we are currently documenting globally provide an advanced warning of the multiple anthropogenic impacts marine mammals are exposed to, highlighting the urgency of the situation. As the health of the world’s Ocean dramatically declines, cetaceans are in trouble: of the 92 species, 12 subspecies and 28 subpopulations of cetaceans that have been identified and assessed to date, 26% are ‘threatened with extinction’ and 11% are ‘near threatened’ (combined: 37%; ref. 49).

What is Ocean Health?

Defining Ocean Health is not straightforward50,51. As Constanza52 already recognized, using the concept of ‘ecosystem health’ utilises the public understanding of human health, making the concept intuitively understood by most stakeholders, thereby assisting the process and opening the door to a multidisciplinary engagement that is of interest to economists, ecologists, philosophers, public policymakers, anthropologists, sociologists and others. In line with later definitions53, the ‘health’ of an ecosystem represents an aggregate of contributions from organisms, species and processes within a defined area rather than a single property. It can be viewed as an indicator that aggregates over components of the overall system or a non-localized emergent system property53. Thus, healthy ecosystems that can sustain ecosystem provisions for humans are vigorous, resilient to external pressures, and able to maintain themselves without human management. They contain organisms and populations that are free of stress-induced pathologies and a functional biodiversity that displays a diversity of responses to external pressures. All expected trophic levels are present and well interconnected, and there is good spatial connectivity amongst subsystems53. Monitoring at this level allows ‘detection of things going wrong’ against a background of system variability and recognises ‘health’ as an emergent property of complex systems53. Using this systemic approach, a healthy system is one that maintains its integrity and is resilient under pressure53. Thus, ecosystem or Ocean Health refers to patterns of system behaviour that are common to both organisms and ecosystems; ill health is recognized by a breakdown of this pattern53.

Ocean Health at the ecosystem level

Research into multiple anthropogenic stressors on marine ecosystems has shown that no area of the global Ocean is unaffected by human influence and that most of the Ocean (59% in 2019) is strongly affected by multiple drivers54,55. Several attempts have been made to define what Ocean Health could or should be51,56,57,58,59. Most widely known is the ‘Ocean Health Index’ (OHI), which provides a framework for an integrated assessment56,57 by evaluating how well marine systems sustainably deliver ten societal goals that people have for a healthy Ocean. The OHI is designed to represent the system’s health through a human lens, because communicating ecosystem health in terms of losses and gains in benefits that people value is seen as a powerful communication tool for managers and wider audiences57. Additional recent global reviews and analyses of river pollution through pharmaceuticals60, impacts from human sewage on coastal ecosystems61 and plastic pollution62 all paint a bleak picture. These analyses may assist in visualizing global threats to marine mammals21, but spatial approaches, like area-based management or marine protected areas (MPA’s; refs. 21,63), will make it difficult to mitigate some anthropogenic impacts on marine mammals, such as pollution of various kinds (including sound pollution), as these do not stop at spatial boundaries64. In fact, such global threats to environmental and human health may hinder the delivery of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals60. While detailed research on the interlinkages between marine mammal health and overall ecosystem health still warrants further investigation19, protected areas in the Ocean cannot be the full solution to managing marine defaunation24.

Ocean Health and public/human health

Having gone from individual animal health via population health to ecosystem health, it is clear that this narrative also has greater implications for life on our planet. In fact, how much Ocean Health affects humans is becoming increasingly evident, with recent studies drawing comparisons between bottlenose dolphins and human reference populations65. After all, these mammals are our equivalent in the Ocean, and what we do to it will affect us sooner or later. Thus, human health is intricately linked to Ocean Health66 and understanding Ocean and human health interactions is the focus of a growing interdisciplinary research field between the natural and social sciences67.

Although humans are exposed to a series of threats from the Ocean (e.g. extreme weather events, flooding, drowning, injury and property damage), disease transmission, and toxic substances are risks shared with marine mammals66. In contrast, a healthy Ocean helps foster healthy people through nutrition, new medical drugs and ‘blue’ spaces for recreation and leisure activities, thereby playing an important role for physical and mental health66—and nature has long been known to be a source of emotional and spiritual sustenance.

Increasingly, we realize our interdependence with the Ocean and our need to measure and assess Ocean Health. Concern over the observed state of global Ocean Health has led researchers to call for a global observing system that should act in parallel with public health systems50,68,69.

Our times of the Anthropocene-planetary boundaries and tipping points

At the planetary level, human domination of Earth’s ecosystems, including the Ocean, has been of concern for some time70,71. The ‘Anthropocene’72 has now been widely recognized as denoting a new geological event in which human activities have taken over global geophysical processes, in many ways outcompeting natural processes73,74. Starting with farming and deforestation, followed by the Industrial Revolution and the rapid burning of fossil fuels, humans have modified three-quarters of the ice-free land surface, altered the atmosphere, Ocean and climate, and in so doing have ushered in the Anthropocene75. The changes involved are of sufficient scale that it is now arguably the most important topic of our age-scientifically, socially and politically. It is the greatest and most urgent challenge humanity faces76.

In this respect, the Ocean is arguably most important in the functioning of the Earth System, because Earth is a blue planet—70% of its surface is covered by the Ocean, which contains between 50% and 80% of all life on Earth, provides 50% of the oxygen we breathe and absorbs 25% of CO2 emissions77,78. Over 90% of heat produced due to excessive, unsustainable emissions has to date been absorbed by the Ocean77,78. It also provides three billion people with nutrition, many of whom depend on seafood as a primary source of protein77. So the Ocean is really the life-support system of our planet, being irrevocably linked to our climate system79.

Warnings of a state shift in Earth’s biosphere, a ‘planetary-scale tipping point’ due to human influence, have been issued for some time80. At the planetary level, a framework of interlinked planetary boundaries associated with the planet’s biophysical processes (or subsystems) has been described to advise governance of the Earth system and meet the challenge of maintaining stable environmental conditions81; because they are interlinked, exceeding one will have implications for others in unpredictable ways, affecting the functioning of the Earth system81. Recent assessments indicate that four of the described nine planetary boundaries have now been exceeded82: climate, land-system and biogeochemical boundaries (namely excessive nutrients), and the genetic diversity component of the biosphere integrity (i.e., biodiversity loss; ref. 82).

Surprisingly little is known about the relationship between biodiversity and the functioning of the Earth System83, but there is considerable evidence that more diverse ecosystems are more resilient to variability and change and thus may be as important as a stable climate in sustaining the Earth System73. Thus as grave as climate change, but far less understood, is the erosion of ecosystem provisions over the past two centuries73. With the Ocean being the largest realm on the planet84, providing 99% of ‘livable’ space by volume84. Accordingly, it harbours the majority of global biodiversity, with more than 300,000 described species and hundreds of thousands yet to be discovered48. Marine ecosystem provisions give benefits to human communities, valued at about 20 trillion US$ per year in 199485. A powerful argument for understanding, evaluating and managing marine ecosystem health is the link from health and resilience to ecosystem function and provisions. Ecosystems and their provisions change naturally, but the rate of change has accelerated dramatically as a result of human activity in the ‘Anthropocene’75,86. Humanity is living off the Earth’s natural capital and utilises more than the ongoing productivity of Earth’s ecosystems can provide, which cannot be sustained indefinitely73. Biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse are considered one of the top five threats humanity will face in the next 10 years87.

Despite the fundamental role of the Ocean and its functioning for the planetary climate and societal well-being, research on planetary boundaries has so far focused predominantly on terrestrial systems and additional boundaries describing biophysical processes inherent in marine systems have been explored only recently70. As such, high-probability, high-impact tipping points in the Ocean’s physical, chemical, and biological systems may go unnoticed76. Approximately 98% of the global Ocean is already affected by multiple stressors57 and several studies have highlighted the changes already going on in our Ocean, such as warming, deoxygenation, and acidification. These cumulative effects may synergistically impact marine biota and state shifts of smaller-scale spatially bounded complex systems (such as a community within a given physiographic region) may overlap and interact with others. Such scenarios may propagate to cause a state shift of the entire global-scale system80,88. Ecosystems under anthropogenic pressure are at risk of losing resilience and, thus, of suffering regime shifts and loss of provisions53, which may well present the quiet tipping points in our Ocean. Biosphere tipping points can trigger abrupt carbon release back into the atmosphere, substantially undermining our life-support system even further and amplifying climate change89. In addition, exceeding tipping points in one system can increase the risk of crossing them in others90.

The rapidly deteriorating individual and population health of marine mammals indicative of deteriorating Ocean Health, may well hint at substantial changes at lower trophic levels. As resilience is the key component of system health, a loss of resilience in biological systems, such as the inability of marine mammal populations to recover to levels that can maintain the integrity of the Ocean system to provide the ecosystem provisions required for climate change mitigation, would be increasing the chances of a regime shift if they are not already occurring90,91,92.

Whales help change climate

The Earth’s history shows us the fragility of climate and ecosystems by means of abruptly occurring high extinction rates of prehistoric life in some eras93,94,95. Today, some baleen whales have declined by 90% and can be considered ‘ecologically extinct’, i.e., although the species in question are still present, they are not sufficiently abundant to fulfil their ecological roles25. Such defaunation can reduce cross-system connectivity, decrease ecosystem stability, and alter patterns of biogeochemical cycling96. And while many of the great whale populations are recovering to near pre-exploitation levels, we see other anthropogenic impacts on the increase (see Fig. 3).

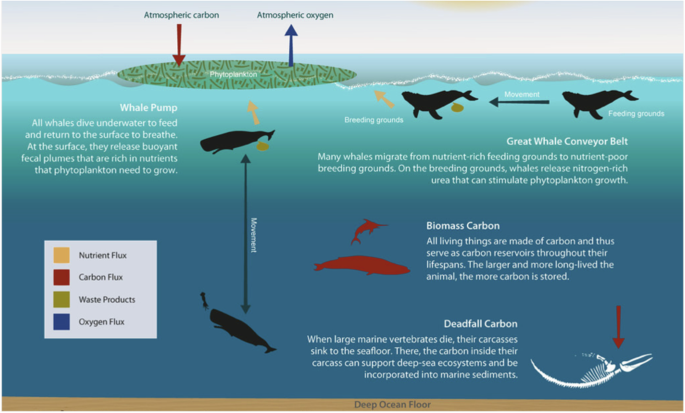

And yet, evidence is increasing that cetaceans play a substantial role in reducing CO2 in the atmosphere and can, infact, be considered ‘Ocean engineers’ due to the vertical cycling of carbon (‘whale pump’) and the horizontal transportation of carbon during the migration between their feeding and breeding grounds (known as the ‘great whale conveyor belt’; Fig. 5; refs. 97,98,99,100). It is estimated that the recovery of whale populations to a status before commercial whaling began would annually decrease carbon dioxide through a capture of about 1.7 billion tonnes from the atmosphere by binding through whale falls101.

Marine mammals as indicators of Ocean Health using a holistic approach to health.

The role of cetaceans as ocean engineers (reproduced with permission-https://www.grida.no/resources/12675; credit: Rob Barnes/Steven Lutz).

While scientists warn that more data are needed to determine the exact role of cetaceans in carbon sequestration102,103, it is increasingly recognized that healthy cetacean communities are vital to the functioning of marine ecosystems104,105. Emerging evidence suggests that other marine mammals, such as small cetaceans106 and sirenians107,108, also play important roles in maintaining Ocean Health. It has been noted that climate change may negatively impact the ecosystem services that whales and other marine mammals may provide109, still multiple, cumulative impacts from other anthropogenic sources remain unconsidered to date.

In this context, it is clear what the threat to Ocean Health, and thus climate, would be if more marine mammal populations were threatened or even disappearing from the Earth.

The next steps

In this respect, long-term ecological research is urgently needed to understand ecosystem complexity, identify natural variability, and disentangle it from anthropogenically-induced or accelerated impacts. Ecological systems usually operate at large temporal scales, which might be overlooked when analysing data collected over short periods of time. Thus, our ability to monitor changes and possibly disentangle anthropogenically caused changes from naturally occurring ones playing out at timescales exceeding human lifetimes requires multi-decadal, possibly even multi-centenary datasets. In addition, baselines need to be established to measure future impact, particularly from anthropogenic sources110; in this respect, marine mammals can provide a chronological record of past environmental conditions in the Ocean and thus past records of Ocean Health. Through hard and semi-hard structures, like whiskers (pinnipeds), teeth (pinnipeds, odontocetes and sirenians) and baleen plates and earplugs (mysticetes), environmental trends in pollution (both noise and chemical pollution: ref. 111), food resources112,113,114, climate115,116 and human activities117 can be traced. This provides information on multi-decadal changes and shifting baselines114 in the Ocean and can be used as environmental tracers. While the disentanglement of the complex contributing factors and their interactions is highly important for marine mammal science, it may take some time to scientifically quantify and describe the rapid changes we are observing in our daily work118. Unfortunately, this is time we may not have for some species and/or populations; in some situations, immediate action is required.

Increasingly, high levels of multiple anthropogenic impacts are being observed in stranded cetaceans and pinnipeds119,120, indicating the current dire state of Ocean Health121. However, rebuilding marine life and thus the restoration and nurturing of Ocean Health is possible122, and the time scales over which this could be achieved are between one and three decades. Possible roadblocks, such as a failure or delay in meeting commitments to reduce existing pressures, may result in a missed window of opportunity to change our current trajectory122.

Responses