Bifidobacterium longum NSP001-derived extracellular vesicles ameliorate ulcerative colitis by modulating T cell responses in gut microbiota-(in)dependent manners

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic, immune-mediated, and nonspecific inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which mainly involves complex interactions between genetic, environmental, microbiota, and immune responses1. Currently, the main clinical options are immunosuppressants, aminosalicylic acid, and glucocorticoid drugs2. However, long-term treatment of such drugs can lead to drug resistance, potential toxicity, and a reduction in the immune resistance of patients. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop an advanced treatment strategy. Most probiotics can be taken orally through the gastrointestinal tract into the colon to support host intestinal health and have been shown to improve colon inflammation3. Researchers have explored how probiotics improve UC through animal models4,5. For example, Lactobacillus intestinalis increased colon retinoic acid metabolism, which relayed its signals by suppressing SAA1/2 production, and consequently restraining Th17 cells to alleviate UC4. Limosilactobacillus reuteri improved intestinal inflammation by improving gut microbiota dysbiosis, protecting the intestinal mucosal barrier, and modulating the immune response5.

However, it is well known that in healthy individuals, the intestinal commensal bacteria located in the outer mucus layer cannot penetrate the highly compacted inner mucus layer and interact with the intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) or lamina propria immune cells directly. In this scenario, a key issue is how the crosstalk between commensal bacteria and the host is established. Recent research indicates that bacterial extracellular vesicles (bEVs) are crucial in mediating communication between microbiota and hosts, including inhibiting pathogens, enhancing intestinal barrier integrity, and regulating immune responses6. The particle size of bEVs is 20–400 nm and contains lipopolysaccharides, peptidoglycans, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids6,7,8. Intestinal commensal bacteria-derived bEVs, released into the gut lumen, can pass through the inner mucus layer and enter the intestinal epithelial cells or immune cells9. Intestinal commensal bacteria such as Clostridium butyricum, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Akkermansia muciniphila-derived bEVs have been found to alleviate UC mice by ameliorating intestinal barrier damage, inhibiting pro-inflammatory factor production, and modulating host immune responses10,11,12.

Bifidobacterium longum, as one of the dominant bacteria in the intestinal tract, has been widely added to probiotic health products due to its good anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities13. B. longum improved intestinal immunopathology during colitis in RAG1 knockout mice14. Our previous study has shown that B. longum NSP001 could ameliorate dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced UC in mice by decreasing intestinal permeability, inhibiting the overproduction of interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and up-regulating the levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)15. Nevertheless, the mechanisms by which B. longum NSP001 regulates the intestinal mucosal barrier, and immune responses still need to be fully understood. Therefore, This study aims to determine whether the ameliorative effects of B. longum NSP001 on UC are mediated by released bEVs.

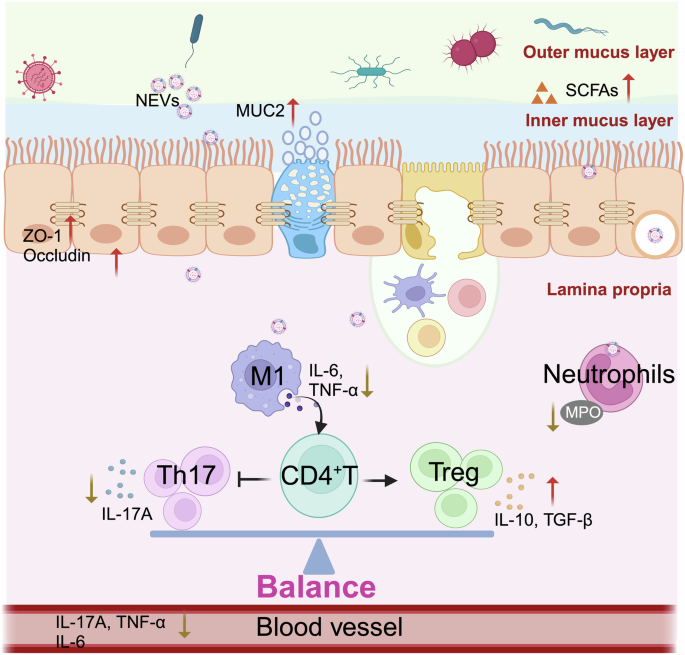

Here, our study showed that NEVs could ameliorate colonic inflammation by improving the intestinal barrier, inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and modulating the differentiation of immune cells. Interestingly, in pseudo-germ-free mice, the alleviating effect of NEVs treatment is not dependent on regulating gut microbiota. Our results indicate that B. longum NSP001 improves UC through the secretion of bEVs. These findings suggest intestinal commensal-derived nanovesicles can prevent and alleviate colonic inflammation, which may be used as a new nanotherapeutic biologic agent.

Results

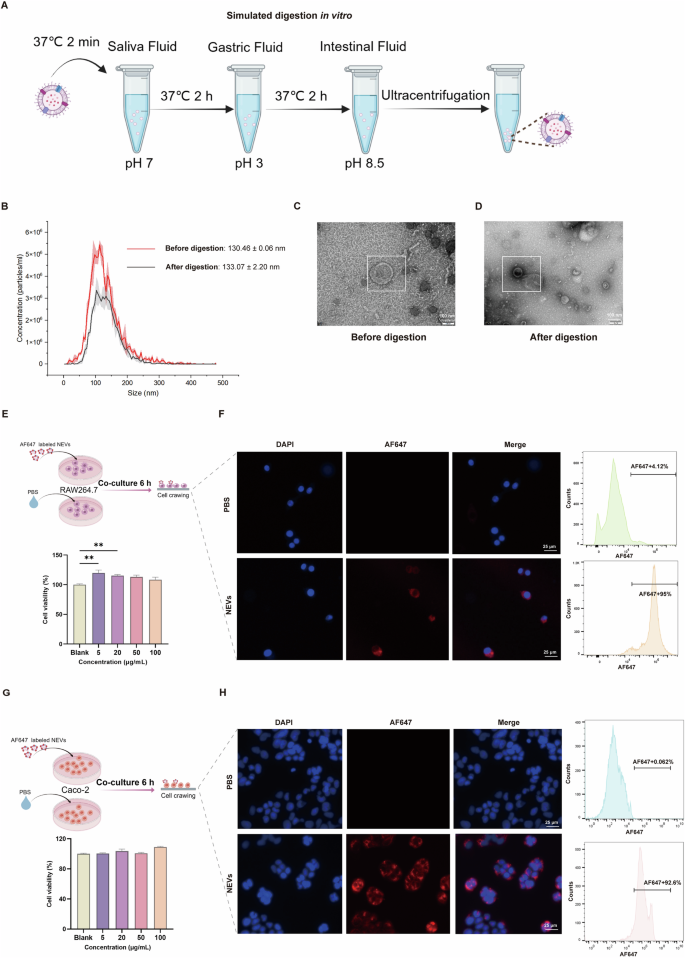

NEVs have favorable biocompatibility

NEVs were obtained through ultracentrifugation following the experimental procedure depicted in Fig. S1A. The morphology and size distribution of NEVs were characterized using TEM and Zetaview, respectively. NEVs exhibited a typical bilayer membrane structure with an average particle size of approximately 130 nm (Supplementary Fig. 1B, C). The stability of nanoformulations in the gastrointestinal environment is a key indicator of their biocompatibility. First, we used the in vitro digestive system to simulate the gastrointestinal environment and evaluate the resistance of NEVs to various digestive fluids (Fig. 1A). The various digestive fluids did not affect the morphology and particle size of NEVs, and no significant number of membrane fragments were observed (Fig. 1B–D). Then, the effect of NEVs on cell viability and the efficiency of being internalized by RAW264.7 and Caco-2 cells were evaluated. We observed that NEVs at concentrations ranging from 5 to 100 μg/mL did not affect the vitality of RAW264.7 and Caco-2 cells by the CCK-8 assay (Fig. 1E, G). This suggested that NEVs exhibit excellent biocompatibility, and the concentration from 5 to 100 μg/mL is guaranteed non-biotoxic concentrations for subsequent cellular experiments. Next, we illustrated the biosafety of NEVs by cellular uptake assays. Inverted fluorescence microscopy images validated that the AF647-labeled NEVs (red fluorescence signals) were successfully internalized by RAW264.7 and Caco-2 cells after co-incubation (Fig. 1F, H). Furthermore, flow cytometry analysis showed that the internalization efficiency of AF647-labeled NEVs by RAW264.7 and Caco-2 cells was 95% and 92.6%, respectively (Fig. 1F, H).

A Schematic diagram of in vitro simulated digestion. In this in vitro simulation of the digestive system, saliva fluid (alpha amylase), gastric fluid (pepsin), and intestinal fluid (pancreatic enzymes and bile acids) are used to profile oral-gastrointestinal digestive conditions. B Plot of particle size before and after digestion of NEVs. C, D Transmission electron microscopy of NEVs before and after digestion, scale bar: 100 nm. E, G The effects of different concentrations of NEVs on the viability of RAW264.7 or Caco-2 cells, n = 6 (The cell experiment diagrams were created with Figdraw). F, H Schematic diagram of NEVs internalization by RAW264.7 or Caco-2 cells. The cell nucleus was stained by DAPI (Blue), and NEVs were labeled by lipophilic carbocyanine dye, AF647 (Red), n = 3, scale bar: 25 μm. NEVs: B. longum NSP001 extracellular vesicles.

In vivo distribution of NEVs

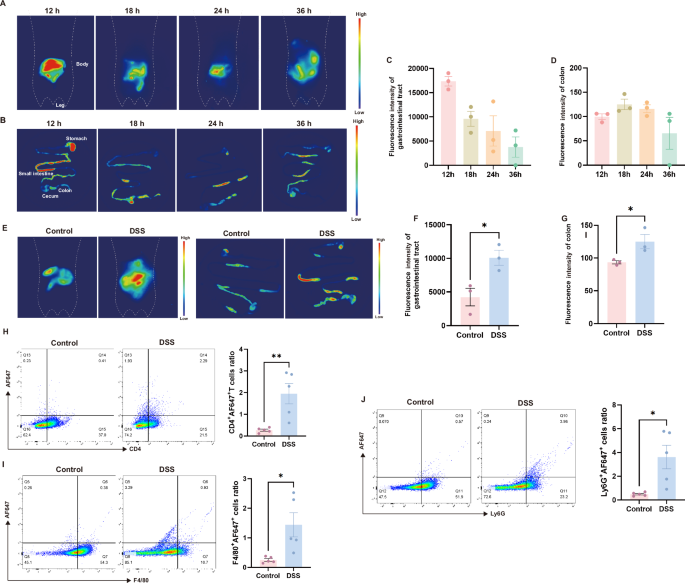

To investigate the in vivo distribution of NEVs, we gavaged AF647-labeled NEVs to mice and performed living imaging experiments. The labeling efficiency of AF647 NEVs was 49.8% (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). The gastrointestinal tract and other organs (heart, liver, lung, spleen, and kidney) were obtained for imaging by the wide-field imaging system. Results showed that the AF647 signaling gradually weakened after gavage for 12 h in the gastrointestinal tract (Fig. 2A–C). The fluorescence intensity of NEVs in the colon was the highest at 18 h (Fig. 2D). The results of colon cryosection at 18 h also showed that NEVs remained in the colon (Supplementary Fig. 3A). In contrast, there was no conspicuous fluorescence of AF647 signals in other organs (Supplementary Fig. 3B).

A Representative images of whole-body live imaging in mice at different time points (n = 3). B Representative fluorescent images of the mouse gastrointestinal tract at different time points (n = 3). C, D Quantitative fluorescence statistics of mouse gastrointestinal tract and colon at different time points (n = 3). E Whole-body and gastrointestinal tract fluorescence images of normal and DSS-induced colitis mice at 18 h (n = 3). F, G Gastrointestinal tract and colon fluorescence quantitative data plots of normal and DSS-induced colitis mice at 18 h (n = 3). H–J FACS was used to determine the population of cells to uptake AF647-labeled NEVs (n = 5). Data were shown as means ± SEM. Significance was assessed using Student’s t-test, giving P values: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. NEVs B. longum NSP001 extracellular vesicles, DSS dextran sulfate sodium, FACS fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Another living imaging experiment was conducted to observe the targeting ability of NEVs. After oral administration of AF647-labeled NEVs for 18 h, the fluorescence intensity in the gastrointestinal tract and the colon was 2.4-fold and 1.4-fold higher in DSS-induced colitis mice than in normal mice, respectively (Fig. 2E–G). The results suggest that NEVs can selectively accumulate in the inflamed lesion sites, which may be an important basis for their anti-inflammatory effects. Additionally, we conducted in vitro experiments to confirm the targeting function of NEVs on inflammatory cells. There was a significant increase in cellular fluorescence intensity following LPS stimulation compared to the untreated group (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Next, we investigated the uptake of NEVs by intestinal immune cells under colon inflammation induced by DSS after gavage for 18 h. The T cells (CD4+) population of AF647-positive cells was 2% in DSS-induced colitis mice, which was 7.5-fold higher than in normal mice (Fig. 2H). For the neutrophils (Ly6G+), this proportion was 3.6% in colitis mice, which was 7.4-fold higher than in normal mice (Fig. 2J). The macrophages (F4/80+) ratio of AF647-positive cells was 1.4% in colitis mice, which was 5.6-fold higher than in normal mice (Fig. 2I). This increase may be due to enhanced activation of immune cells in the lamina propria of the colon, along with increased permeability of the intestinal barrier, resulting in more NEVs entering the lamina propria and being internalized by uptake by resident immune cells16,17.

NEVs alleviate DSS-induced colitis severity

We first explored the in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of NEVs using the LPS-induced RAW264.7 cell inflammation model (Supplementary Fig. 5A). The results showed that NEVs inhibited the production of M1-type macrophages and the secretion of the related pro-inflammatory cytokines IL6 and TNF-α, suggesting that NEVs have good anti-inflammatory activity in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 5B–F).

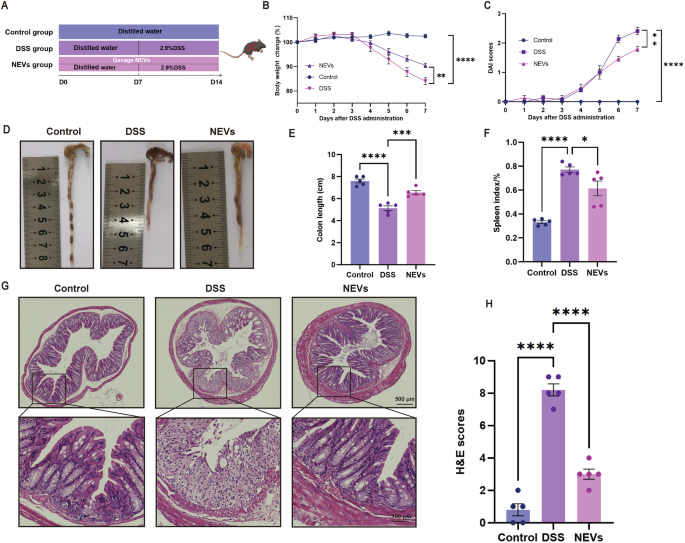

Further, we investigated the effects of NEVs on DSS-induced colitis mice, as shown in Fig. 3A. NEVs treatment significantly prevented DSS-induced colitis mice from lower body weight, higher disease activity index (DAI), and shorter colon length (Fig. 3B–E). The development of colitis causes a systemic inflammatory response, leading to splenomegaly18. NEVs treatment reversed the increase of spleen index induced by DSS in mice (Fig. 3F). Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining showed that the control mice had intact colon with well-arranged epithelial cells. In contrast, the colonic epithelial cells of the DSS-treated group were disorganized or even lost, with apparent inflammatory cell infiltration in the lamina propria and submucosa and missing crypt structures (Fig. 3G, H). Treatment with NEVs effectively improved the pathological morphology of the colon in DSS-induced colitis mice and prevented the migration of inflammatory cells (Fig. 3G, H).

A Schematic diagram of the animal experimental program (n = 5). B Changes in body weight (n = 5). C Disease activity index (DAI) scores (n = 5). D Representative images of colon length (n = 5). E Quantification of colon length (n = 5). F Spleen index, spleen index % = spleen mass/mouse body weight × 100% (n = 5). G Representative images of HE staining (n = 5), scale bar: 500 μm and 100 μm. H HE staining score (n = 5). Data were shown as means ± SEM. Significance was assessed using the one-way or two-way ANOVA test, giving P values: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. NEVs B. longum NSP001 extracellular vesicles, DSS dextran sulfate sodium, FACS fluorescence-activated cell sorting, HE hematoxylin-eosin.

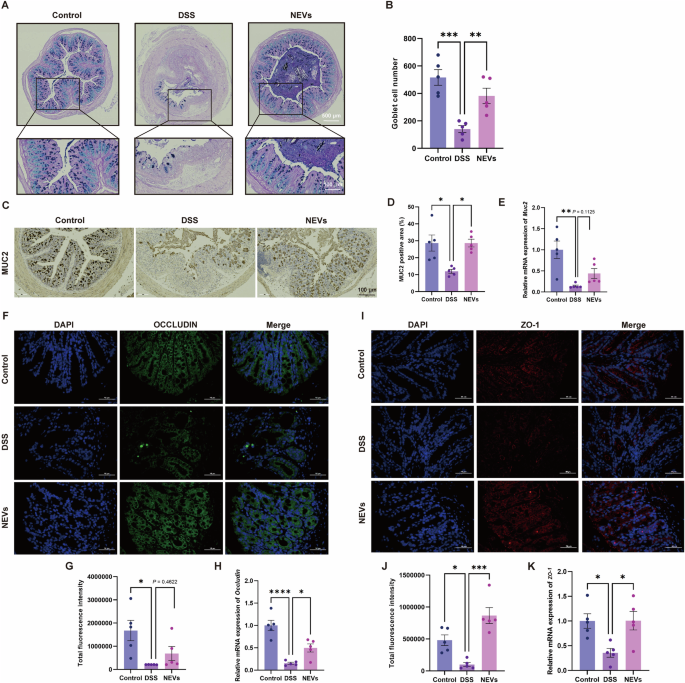

NEVs ameliorate intestinal barrier disruption in DSS-induced colitis mice

Goblet cells and secreted Mucin 2 (MUC2) play an important role in maintaining the intestinal mucosal barrier in UC19. Alcian blue periodic acid-schiff (AB-PAS) staining results showed that goblet cells were abundant and well-arranged in the control group (Fig. 4A, B). NEVs treatment significantly reversed the reduction of goblet cell numbers in DSS-induced colitis mice (Fig. 4A, B). DSS treatment significantly inhibited the protein expression of MUC2 in the colon, while gavage of NEVs promoted the production of MUC2 (Fig. 4C, D). The mRNA results showed that NEVs increased the level of Muc2 expression, but there was no statistical difference (Fig. 4E).

A Representative image of AB-PAS staining (n = 5), scale bar: 100 μm. B The number of goblet cells counted for the colon (n = 5). C Representative images of MUC2 immunohistochemistry (n = 5), scale bar: 100 μm. F, I Representative images of colonic ZO-1 and OCCLUDIN measured by immunofluorescence (n = 5), scale bar: 50 μm. D, G, J Quantification of MUC2, ZO-1, and OCCLUDIN (n = 5). E, H, K The mRNA expression levels of Muc2, Zo-1, and Occludin in the colon (n = 5). Data were shown as means ± SEM. Significance was assessed using the one-way ANOVA test, giving P values: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. NEVs B. longum NSP001 extracellular vesicles, DSS dextran sulfate sodium, AB-PAS alcian blue periodic acid-schiff.

Tight junction proteins (ZO-1 and OCCLUDIN) are the indicators of the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier and paracellular permeability. As shown in Fig. 4F–K, NEVs treatment significantly restored the levels of ZO-1 and OCCLUDIN in DSS-induced colitis mice, bringing their protein levels near those in the control group. Also, we observed a tendency at the gene level that was consistent with the protein level (Fig. 4F–K). Together, all these findings demonstrated that NEVs exhibited effective recovery of the intestinal barrier function.

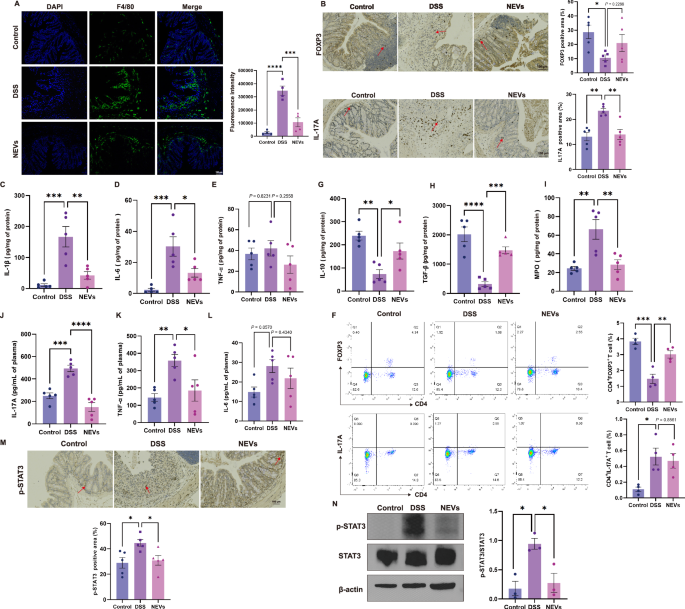

NEVs ameliorate colitis associated with immune modulation

Damage to the intestinal barrier causes abnormal activation of immune cells such as macrophages and T cells20. Immunofluorescence results showed that the number of macrophages in DSS-induced colitis mice decreased after NEVs gavage (Fig. 5A). Then we measured the levels of M1-related pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6. As expected, these pro-inflammatory cytokines markedly increased in mice fed on DSS (Fig. 5C–E). Upon NEVs treatment, DSS-induced elevation of cytokines was suppressed (Fig. 5C–E). The mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines had a similar trend to the protein results (Supplementary Fig. 6A–C). These results indicated that NEVs treatment significantly inhibited macrophage infiltration and the production of M1-related inflammatory cytokines.

A Representative image and semi-quantitative statistical chart of macrophage proportion in the colon by immunofluorescence detection (n = 4), scale bar: 100 μm. B Immunohistochemical detection of the ratio and quantitative statistical graph of Th17 and Treg cells in the colon (n = 5), scale bar: 100 μm. F The proportion of Tregs and Th17 in the spleen (n = 4). C–E, G–I Levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TGF-β, TNF-α, and MPO in the colon (n = 5). J–L Levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-17A, IL-6, and TNF-α in plasma (n = 5). M Immunohistochemical detection of the ratio of p-STAT3 in the colon (n = 5), scale bar: 100 μm. N Protein expression levels of p-STAT3 and STAT3 in the colon (n = 3). Data were shown as means ± SEM. Significance was assessed using the one-way ANOVA test, giving P values: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. NEVs B. longum NSP001 extracellular vesicles, DSS dextran sulfate sodium, MPO myeloperoxidase.

Next, to assess the impact of NEVs on the differentiation of Th17 and Treg cells, we analyzed the proportion of these cell types in both the spleen and colon. Immunohistochemistry results revealed a significant increase in the population of Th17 cells and a notable reduction in the proportion of Tregs in the DSS-treated group (Fig. 5B). Following the administration of NEVs, there was a decrease in the number of Th17 cells and an increase in Tregs frequency (Fig. 5B). NEVs treatment promoted Tregs-related anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β expression levels in DSS-induced colitis mice (Fig. 5G, H). To confirm this observation, we also measured the gene expression related to Il-17a, Il-10, and Tgf-β, which had a similar trend to the protein results (Supplementary Fig. 6E–G). These findings indicate that NEVs can inhibit the generation of Th17 cells in the colon while promoting the differentiation of Treg cells. We also detected the proportion of Th17 and Tregs in the spleen. NEVs treatment significantly promoted the generation of Tregs in the spleen but had no significant impact on the generation of Th17 cells (Fig. 5F).

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity is a key indicator of neutrophil infiltration in acute inflammation. We examined MPO activity in the colon (Fig. 5I). The NEVs-treated group suppressed DSS-induced elevations of MPO activity in the mice colon, indicating that NEVs effectively prevent neutrophil infiltration.

In addition, colitis can increase pro-inflammatory cytokines in plasma21. Therefore, we measured the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-17A, TNF-β, and IL-6 in plasma (Fig. 5J–L). After NEVs treatment, there was a downward trend in all three pro-inflammatory cytokines in plasma (Fig. 5J–L). This indicates that oral administration of NEVs can improve systemic inflammation induced by DSS in mice.

Previous studies have shown that IL-6 can activate the cytoplasmic transcription factor STAT3. Phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3) enters the nucleus and binds to target genes, activating transcription and producing pro-inflammatory cytokines22,23. Therefore, we investigated whether NEVs can inhibit the phosphorylation of STAT3 and thus suppress the production of related pro-inflammatory cytokines in a DSS-induced colitis model. The proportion of p-STAT3-positive cells in the colon of DSS-treated group mice significantly increased (P < 0.05). However, after treatment with NEVs, the number of p-STAT3-positive cells reduced considerably (Fig. 5M). To further confirm the finding, we conducted a western immunoblot analysis to detect the expression of relevant proteins. The results showed that after NEVs treatment, the p-STAT3 level in the colon decreased significantly, and the ratio of p-STAT3/STAT3 was lower than that in the DSS-treated group (Fig. 5N).

These results demonstrate that oral administration of NEVs can regulate immune dysregulation in DSS-induced colitis mice by influencing the differentiation of immune cells to restore immune function. Specifically, NEVs reduced the number of macrophages and Th17 cells while increasing the number of anti-inflammatory Treg cells.

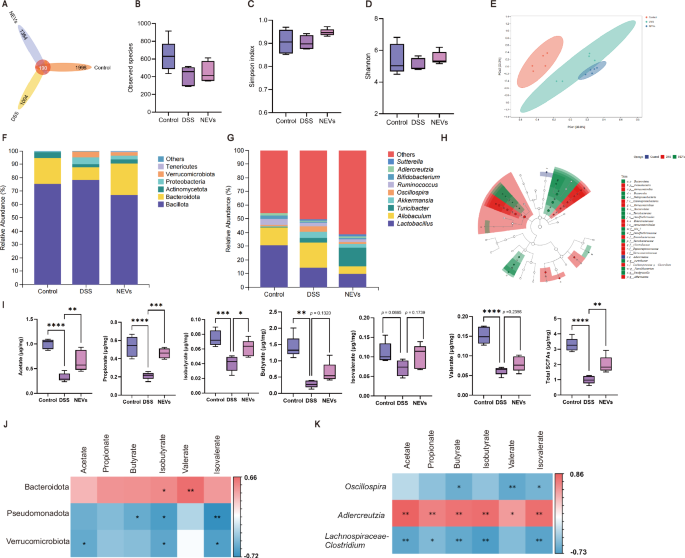

NEVs modulate gut microbiota composition and SCFAs production in DSS-induced colitis mice

Gut microbiota can influence host immune tolerance responses and intestinal homeostasis, and intestinal microecological disorder is a critical pathogenetic factor in colitis24. Therefore, we analyzed the gut microbiota of mice. There was no sharp increase in the rarefaction curves, indicating that the sample sequencing depth was sufficient for data analysis (Supplementary Fig. 7A). The Venn diagram showed that a total of 4366 ASVs were identified in the three groups of fecal samples, with 1004 OTUs in the DSS-treated group being different from the control group (Fig. 6A). There was no statistically significant difference in α-diversity among the three groups (Fig. 6B–D). Then, β-diversity analysis was presented on PCoA plot to assess the degree of similarity between microbial communities. The results showed separation among groups, indicating that the DSS treatment affected the gut microbiota composition and oral administration of NEVs could alter the gut microbiota composition of mice to some extent (Fig. 6E).

A Venn plot. B–D α-diversity, evaluated by B observed species, C Simpson, and D Shannon index. E β-diversity, PCoA plot (n = 5). F relative abundance at the phylum level (n = 5). G relative abundance at the genus level. H Cladogram from LEfSe analysis: rings represent different classification levels (n = 5) (LDA > 3.5). I SCFAs content. From left to right, they are acetate, propionate, isobutyrate, butyrate, isovalerate, valerate, and total SCFAs (n = 5). J Association analysis between the abundance of gut microbiota at the phylum level and SCFAs (n = 5). K Association analysis between the abundance of gut microbiota at the genus level and SCFAs (n = 5). Data were shown as means ± SEM. Significance was assessed using the one-way ANOVA test, giving P values: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. NEVs B. longum NSP001 extracellular vesicles, DSS dextran sulfate sodium, PCoA principal coordinate analysis, SCFAs short-chain fatty acids.

Subsequently, we determined the relative abundance of the gut microbiota at different classification levels. The top six microbial communities ranked at the phylum level are shown in Fig. 6F. Compared with the control group, the structure of the gut microbiota of mice in the DSS-treated group was significantly altered, which was mainly characterized by an increase in the abundance of Bacillota, Pseudomonadota, and Verrucomicrobiota and a decrease in the abundance of Bacteroidota. However, the proportions of Bacteroidota significantly increased after NEVs treatment (Supplementary Fig. 7B), and the abundance of Bacillota decreased.

The top ten microbial communities ranked at the genus level are shown in Fig. 6G. Compared to the control group, the abundance of Allobaculum and Oscillospira increased, and the abundance of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium decreased in the intestinal tract of the DSS-induced colitis mice. However, the abundance of Allobaculum decreased, and the abundance of Turicibacter increased after the oral administration of NEVs. In addition, the relative abundance of important taxa was assessed using linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe). Based on linear discriminant analysis (LDA) > 3.5, the results showed that only one type of differentially abundant taxon, Adlercreutzia, was present in the control group, and 12 dominant microbial communities were identified in both the DSS and NEVs-treated groups, with an increase in the abundance of Pseudomonas and Verrucomicrobiaceae in the DSS-treated group (Fig. 6H, Supplementary Fig. 7C).

In addition, SCFAs, metabolites of the gut microbiota, play an essential physiological role in colitis by promoting the formation of tight junction proteins and mucins, inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and regulating the differentiation of intestinal intrinsic immune cells18,25. Therefore, we measured the levels of SCFAs in the cecum contents of mice in each group (Fig. 6I). The levels of SCFAs in DSS-induced colitis mice were significantly lower than in control mice. In contrast, the levels of SCFAs in the intestinal tract of the mice increased by the gavage of NEVs. Specifically, the levels of acetate, propionate, and isobutyrate increased considerably, and the levels of butyrate, valerate, and isovalerate increased slightly but were not statistically distinguishable. We performed Spearman analysis further to show the relationship between gut microbiota and SCFAs. At the phylum level, Bacteroidota showed a significant positive correlation with the production of isobutyrate and valerate. In contrast, Pseudomonadota and Verrucomicrobiota showed a negative correlation with the production of SCFAs (Fig. 6J). At the genus level, Adlercreutzia significantly positively correlated with SCFAs, and Oscillospira and Lachnospiraceae-Clostridium negatively correlated with the production of SCFAs (Fig. 6K). These results demonstrated that NEVs could alleviate colitis in mice by influencing the gut microbiota composition and its metabolites.

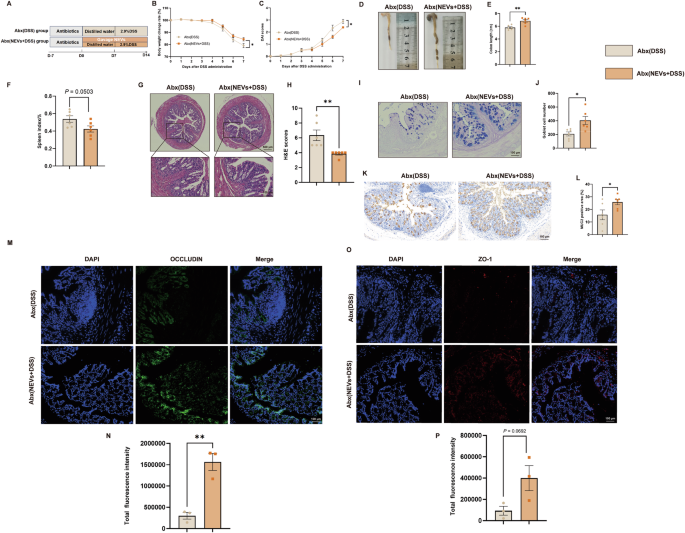

NEVs improve inflammation in DSS-induced colitis mice in the depletion of gut microbiota

We next used pseudo-germ-free mice to investigate whether the beneficial effects of NEVs on DSS-induced colitis in mice depend on the gut microbiota. The depletion efficiency of gut microbiota in mice was 98% (Supplementary Fig. 8). Surprisingly, NEVs treatment still prevented weight loss, DAI rise, spleen index rise, and colon length shorting in DSS-induced colitis mice (Fig. 7A–F). This indicates that even without gut microbiota, NEVs can still improve colitis (Fig. 7A–F). The HE results showed that the colon in the Abx (NEVs+DSS) group was more intact than in the Abx (DSS) group (Fig. 7G, H). The AB-PAS staining results indicated that the number of goblet cells in the colon of the Abx (NEVs + DSS) group was significantly higher than that in the Abx (DSS) group (Fig. 7I, J). Immunohistochemical detection of MUC2 expression revealed that MUC2 levels in the colon of the Abx (DSS) group were significantly lower than those in the Abx (NEVs+DSS) group (Fig. 7K, L). Immunofluorescence detection of ZO-1 and OCCLUDIN showed an increase in tight junction protein expression after NEVs administration (Fig. 7M–P). These results suggest that NEVs can improve intestinal barrier damage even in mice with depleted gut microbiota.

A Schematic diagram. B Changes in body weight (n = 6). C DAI scores (n = 6). D, E Representative images of colon length and quantification of colon length (n = 6). F Spleen index (n = 6). G, H Representative images of HE staining and score (n = 6). I, J Representative images of AB-PAS staining and the number of goblet cells counted for the colon (n = 6), scale bar: 100 μm. K, L Representative images of MUC2 immunohistochemistry (n = 6), scale bar: 100 μm. M–P Representative images of ZO-1 and OCCLUDIN measured by immunofluorescence (n = 3), scale bar: 100 μm. Data were shown as means ± SEM. Significance was assessed using Student’s t-test, giving P values: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. NEVs B. longum NSP001 extracellular vesicles, DSS dextran sulfate sodium, HE hematoxylin–eosin, AB-PAS alcian blue periodic acid-Schiff.

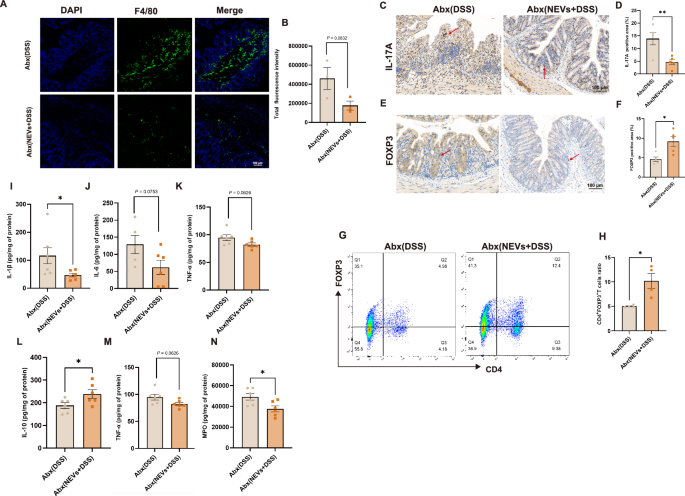

NEVs regulate the differentiation of immune cells in the depletion of gut microbiota

Metabolites of gut microbiota, such as butyrate and deoxycholate, have been shown to regulate immune cell differentiation directly. Butyrate promotes the differentiation of CD4+ T cells toward Treg cells and decreases the proportion of Th17 cells by activating the PPARγ receptor26. The immunofluorescence results showed that the number of macrophages was higher in the Abx (DSS) group than in the Abx (NEVs+DSS) group (Fig. 8A, B). Colon immunohistochemistry results showed an increase in the number of Treg cells and a decrease in the number of Th17 cells in the Abx (NEVs+DSS) group compared to the Abx (DSS) group (Fig. 8C–F). Flow analysis showed that NEVs significantly promoted Tregs cell production in the spleen (Fig. 8G, H). Similarly, in the gut microbiota depletion group, we measured cytokine levels. The levels of IL-6, MPO, IL-1β, and TNF-αdecreased, and the levels of IL-10 and TGF-βincreased in the Abx (NEVs+DSS) group compared to the Abx (DSS) group (Fig. 8I–N). These results suggest that NEVs can influence immune cell differentiation and the secretion of relevant inflammatory cytokines, even without gut microbiota.

A, B Representative image of macrophage proportion in the colon by immunofluorescence detection (n = 3), scar bar: 100 μm. C–F Immunohistochemical detection of the ratio of Th17 and Tregs in the colon (n = 4), scale bar: 100 μm. G, H The proportion of Tregs in the spleen was determined by flow cytometry (n = 4). I–N Detection of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, TGF-β, and MPO production in the colon (n = 6). Data were shown as means ± SEM. Significance was assessed using Student’s t-test, giving P values: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. NEVs B. longum NSP001 extracellular vesicles, DSS dextran sulfate sodium, MPO myeloperoxidase.

Discussion

This study is the first to investigate the therapeutic effects of B. longum NSP001-derived bEVs on intestinal inflammation associated with UC. Probiotics, and B. longum in particular, are known for their health benefits, including inflammation regulation, immune modulation, and promoting gut health27. However, their potential role in managing UC-associated intestinal inflammation remains unclear. Our results demonstrated that bEVs derived from B. longum NSP001 can alleviate intestinal inflammation in mice via ameliorating intestinal barrier damage, modulating immune cell differentiation, and promoting the production of SCFAs. Excitingly, we demonstrated that the anti-inflammatory effects of NEVs are independent of gut microbiota through pseudo-germ-free animal experiments. These findings support the hypothesis that intestinal bacterial-derived bEVs can cross the sterile inner mucus layer and interact directly with host resident immune cells, triggering downstream responses and physiological effects in the host body28.

Firstly, we investigated the oral stability and in vivo distribution of NEVs. Using the in vitro simulated digestive system to imitate the gastrointestinal environment29, we demonstrated no significant changes in the size and morphology of NEVs after exposure to harsh oral–gastric–intestinal digestion conditions. Nevertheless, the differences in the composition and bioactivity of NEVs before and after digestion must be further investigated. Accordingly, orally administered AF647-labeled NEVs were observed in the intestine. Further research showed that AF647-labeled NEVs were more taken up by T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells in DSS-induced colitis mice than in normal mice. The result showed that more immune cells were activated in the intestines of DSS-induced colonic disease. The results suggested that NEVs appear to accumulate in the inflamed colon selectively, consistent with previous findings that Escherichia coli 1917-derived OMVs could target and enrich at sites of colonic inflammation in IBD mice30.

The anti-inflammatory effect of bEVs isolated from probiotics has been recently reported in various in vitro studies31,32. Accordingly, we showed that bEVs derived from B. longum NSP001 exerted similar anti-inflammatory activity toward macrophages. NEVs could inhibit the differentiation of macrophages into the M1 type and suppress the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, which was in line with a previous study33. Next, we investigated whether NEVs could improve colon inflammation in DSS-induced colitis mice. UC is closely associated with impaired intestinal barrier function. The integrity of the intestinal barrier primarily involves the mucin secreted by goblet cells and the tight junction proteins between epithelial cells34. Previous research has demonstrated that DSS induces a substantial reduction in goblet cells and downregulation of tight junction proteins in the intestines of mice, which leads to an increase in intestinal permeability18. This allows various bacteria-derived endotoxins (or LPS) to enter the bloodstream through the intestinal mucosa, triggering an inflammatory response in the host. Our research indicates that the administration of NEVs significantly improved the reduction of goblet cells and MUC2 in DSS-induced colitis mice while increasing the expression of ZO-1 and OCCLUDIN. This suggests that NEVs play a role in repairing damaged intestinal barriers and alleviating UC.

Intestinal barrier disruption allows pathogens and other antigens to enter the mucosal layer, activating the host’s immune mechanisms35,36. Both innate and adaptive immune cells play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of UC37. Neutrophils and macrophages, as part of the first line of defense of the innate immune system, are essential for maintaining intestinal homeostasis. Excessive activation of neutrophils and macrophages in the intestines of IBD patients can further exacerbate the inflammatory response. Evidence suggests that overactivated neutrophils release ROS and MPO, exacerbating colon damage and accelerating the apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells37. Furthermore, excessive accumulation of ROS, LPS, and GM-CSF can induce macrophages to differentiate into pro-inflammatory M1 type, leading to the release of large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, thereby worsening the progression of colon inflammation. In our study, we observed a significant increase in the expression of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, and MPO in the colon and an increase in the proportion of macrophages following DSS administration. However, oral NEVs treatment reversed these changes and alleviated acute inflammatory injury.

Macrophages phagocytose pathogens and present antigens to T cells, thereby activating the immune response of T cells. Based on the expression of cell surface molecules, T cells are divided into CD8+ T cells (cytotoxic T cells) and CD4+ T cells. CD4 T cells were further categorized as Th and Tregs. Th17 cells primarily secrete IL-17A, a major pathogenic factor in various autoimmune diseases such as IBD and psoriasis. In contrast, Tregs predominantly secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β and are considered specialized inhibitory cytokines for various immune responses and inflammation. Th17/Treg cells are usually balanced and work together to maintain intestinal immune homeostasis. Still, once the balance is disturbed, especially with an excessive increase in Th17 cells, it contributes to the worsening of IBD38. Previous studies have demonstrated that the proportion of Th17 cells and IL-17A in the peripheral blood of IBD patients is significantly elevated, while the proportion of Treg cells and IL-10 has decreased39. In this study, it was observed that in UC mice, there is an increase in the proportion of Th17 cells and expression levels of IL-17A in the colon, along with a decrease in the proportion of Treg cells and expression levels of IL-10 and TGF-β. These findings align with those reported by Liu et al. 40 NEVs treatment significantly inhibited the increase of Th17 cells and the decrease of the Treg cell ratio in colons. This suggests that NEVs may potentially influence CD4+T cell differentiation to restore Th17/Treg balance, thereby alleviating UC.

Gut microbiota and its metabolites can influence intestinal immune homeostasis and thus play an essential role in the occurrence and development of UC41. Our results showed that the gavage of NEVs affected the composition of gut microbiota and promoted the production of SCFAs. Specifically, NEVs treatment reversed the decrease in the abundance of Bacteroidota phylum in DSS-induced colitis mice. Further analysis showed that Adlercreutzia was positively associated with the production of SCFAs. Previous study has demonstrated that Adlercreutzia has antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities, which is significantly reduced in patients with IBD42.

To investigate whether the alleviation of UC by NEVs was dependent on the modulation of gut microbiota, we depleted the gut microbiota of mice using quadruple antibiotics, and the epigenetic indexes showed that the administration of NEVs still alleviated DSS-induced colitis and still modulated the differentiation of immune cells and the production of relevant inflammatory cytokines. Interestingly, our findings contrast with those of Liang et al.43 Through antibiotic clearance experiments, they concluded that C. butyricum-derived CMVs affect macrophage polarization in a microbiota-dependent manner. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory effects of C. butyricum-derived CMVs on colitis disappear with the loss of gut microbiota43. However, much literature on probiotic EVs indicates that bEVs can directly interact with cells. F. prausnitzii CMVs could significantly increase the expression of tight junction protein-related genes (ZO-1, OCCLUDIN, ANGPTL4, PPARs) in Caco-2 cells10. E. coli Nissle 1917-derived OMVs can be internalized by RAW264.7 cells, which subsequently promote the secretion of the anti-inflammatory factor IL-10 in RAW264.7 cells and increase the antibacterial activity of macrophages, indicating that bEVs can regulate the host immune response31. CMVs derived from B. longum, C. butyricum, and Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 can all stimulate innate immune responses in RAW264.7 and dendritic cells44. Lactobacillus-derived CMVs can inhibit the rise of NO and pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) in the LPS-induced RAW264.7 cell model and have favorable immune regulatory effects45.

Therefore, we hypothesize that orally administered probiotic-derived bEVs, due to their nanoscale size and good bio-permeability, may be able to penetrate the intestinal mucosal layer and directly interact with the IEC or immune cells. Subsequently, it may play a role in improving intestinal barrier damage and maintaining immune cell balance. Moreover, this improvement effect could persist even in the case of depletion of the gut microbiota. Indeed, further experiments are needed to conduct in-depth research on the specific substances that play an anti-inflammatory role in NEVs and the mechanisms by which NEVs rely to enter host cells.

In conclusion, we present a natural and non-toxic nano-vesicle that can alleviate DSS-induced colitis by suppressing pro-inflammation secretion, regulating T-cell differentiation, and possessing the generation of SCFAs (Fig. 9). This nano-system, exemplified by NEVs, may become a novel postbiotic agent for clinical application in the prevention and treatment of UC.

Bifidobacterium longum-derived extracellular vesicles (NEVs) ameliorate DSS-induced colonic injury by enhancing tight junction protein expression, promoting SCFAs production, regulating gut microbiota composition, and regulating T cell differentiation. Created with biorender.

Methods

Extraction of NEVs

B. longum NSP001 was obtained from the State Key Laboratory of Food Science and Resources, Nanchang University, and cultured in MRS Broth medium (Haibo, China) under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 36 h. The bacterial culture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min, and the obtained supernatant was filtered (0.22 μm) to remove bacterial debris and other impurities. The filtrate was ultracentrifuged into spheres in an ultrahigh-speed centrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) at 150,000g at 4 °C for 2 h. The pellet was then re-suspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Solarbio, China). The microspheres were resuspended in PBS, and the protein concentration of NEVs was quantified using a BCA assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) and stored in portions at −80 °C.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis

TEM was used to observe the morphological characteristics of NEVs46. Briefly, 20 μL of NEVs solution was pipetted and added dropwise onto a copper grid, and the excess solution was blotted out with filter paper and left for 1 min. An equal amount of 2% phosphotungstic acid (SPI-Chem, USA) was added dropwise and left for 3 minutes, and the remaining liquid was removed by filter paper. After drying, it was imaged under a TEM (JEOL, JEM1400, Japan).

Zetaview analysis

To detect the diameter and particle number of NEVs, nanoparticle tracking analysis was performed using a Zetaview PMX120 (Particle Metrix, Germany). The instrument was calibrated using polystyrene particles (110 nm) before measurement. Samples were diluted using 1× PBS during measurements, and 11 different cell locations were recorded. The data collected for each sample was analyzed using Zetaview 8.04.02 software.

Cell viability and cellular uptake assay

The Caco-2 and RAW264.7 cells were cultured on the 96-well plates for 6 h in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Solarbio, China) supplemented with 20% or 10% FBS (Gibco, Australia) and 1% penicillin (Solarbio, China) and streptomycin at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide. After cells adhered to the wall, the supernatant was aspirated, and cells were incubated with the addition of NEVs-containing medium at 200, 50, and 10 μg/mL concentrations. After being cocultured for 24 h, the medium was replaced with DMEM medium with 10% cell counting kit-8 (Dojindo, Japan), and the reaction was carried out at 37 °C for 30 minutes. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using an enzyme meter.

The cells were cultured in 24-well plates lined with cell crawls and incubated for 6 h. The experimental group was AF647-labeled NEVs, and the control group was the AF647 plus PBS group, which was co-cultured with the cells for 6 h. The supernatant was aspirated, and cells were washed three times using PBS. Paraformaldehyde (4%, Biosharp, China) was added to fix cells for 15 min, and then cells were rewashed three times using PBS. Antifade mounting medium with DAPI (Beyotime, China) was added to the slide, and the cell crawler was covered in the solution for 20 minutes. Inverted fluorescence microscopy was used to observe the cellular uptake (Nikon Eclipse Ti-SR, Nikon Co., Japan).

Macrophage polarization analysis

RAW264.7 cells (1 × 106 cells/mL) were cultured in 12-well plates and treated with 1 μg/mL LPS (LPS group), 20 μg/mL NEVs (low-NEVs-treated group), or 50 μg/mL NEVs (high-NEVs-treated group), while the control group received no treatment. The cells were stimulated for 18 h. After incubation, the cell culture supernatants were collected and stored at −20 °C to measure inflammatory cytokines, and the cells from each well were collected for cytometry or Q-PCR. Specifically, the antibody for flow cytometry was CD86 (BD Pharmingen, USA). PBS was used to clean cells and as a flow buffer.

Stability of NEVs in the simulated digestive system in vitro

Simulated saliva, gastric, and intestinal fluids were prepared following the method of Zhang et al.47. The resulting NEVs digest was first centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 20 minutes to remove impurities, then centrifuged at 150,000g for 2 h to concentrate. Zetaview and TEM were used to observe the changes in morphology and particle size of NEVs before and after digestion.

Animal models

All animal experiments were performed under the Guidelines for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and were approved by the Experimental Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanchang University, number IACUC-20221030001. Male C57BL/6J mice, 6 weeks of age and weighing around 20 g, were purchased from Charles River (Beijing, China). All mice were fed in a constant temperature and humidity (12/12 h) alternating light and dark environment for 7 days and then randomly divided into control, model, and NEVs-treated groups (n = 5). The model group was given 0.2 mL of PBS, and NEVs were given 0.2 mL of 150 μg/mL NEVs solution for 14 days, and 2.9% (w/v) DSS (molecular weight: 36,000–50,000, MP Biochemical) was added to the drinking water from day 7 to 14 for the DSS and NEV groups. Mice body weight and feces were recorded and scored daily during DSS treatment. Each mouse was scored according to the parameters (Supplementary Table 1), and the average of the three items was taken as the DAI index of the mice48. On day 14, the mice were sacrificed. Blood from the eyeballs was collected in the anticoagulant tube, and cecal contents and colons were collected. The lengths of the colons were measured; the spleens were weighed; plasma, colon, colon contents, and cecal contents were stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

Biodistribution of NEVs

AF647-labeled NEVs were administered orally to DSS-induced colitis mice. The distribution of NEVs in vivo was captured and imaged at different time points using a wide-field imaging system (Bios-WFM, KAYJA-OPTICS, China). The mice were immediately dissected, and the gastrointestinal tract, heart, liver, lungs, spleen, and kidneys were removed for in vivo imaging.

Gut microbiota depletion

After 7 days of mouse domestication, feces were collected and stored at −20 °C. Mice were gavaged daily with 0.2 mL of a quadruple antibiotic mixture: vancomycin (50 mg/kg, Sigma), metronidazole (100 mg/kg, Sigma), kanamycin (100 mg/kg, Sigma), and ampicillin (100 mg/kg, Sigma) for 7 days, and feces were collected on day 749. Gut microbial depletion was confirmed by assessing total fecal DNA in mice before and after antibiotic administration. Subsequently, mice were randomly divided into the antibiotic+DSS-treated group (Abx + DSS) and the antibiotic + NEVs + DSS-treated group (Abx + NEVs + DSS), with 5 mice in each group. For 14 days, the Abx (DSS) group was given 0.2 mL of PBS, the Abx (NEVs + DSS) mice were given a PBS solution containing 30 μg of NEVs, and 2.9% DSS water was given for the last 7 days.

Isolation of spleen cells and colon lamina propria (LP) cells

It was added to a 6-well plate with 2 mL of ACK lysis buffer (Elabscience, Chian), and spleens were ground with a 5 mL syringe soft-tip plug on a 70 μm cell strainer. The cell strainer was rinsed with 5 mL of pre-cooled PBS, and the cell suspension was collected in a 15-mL centrifuge tube at 1200 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was poured off, and 3 mL of PBS was added at 1200 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was poured off, and the splenocytes were resuspended in 2 mL of PBS for cell counting. Dilute the single-cell suspension to the appropriate concentration.

After 18 h of oral administration of AF647-labeled NEVs to mice, a 0.5 cm section of the colon was collected. The intestine was then longitudinally opened and rinsed in pre-cooled PBS. The colon was incubated in 5 mM EDTA (Solarbio, China) and 2 mM dithiothreitol (Solarbio, China) for 20 min at 37 °C to remove the intestinal epithelial sheets. The remaining tissue was placed in a 6-well plate containing 3 mL of digestion solution [collagenase IV (0.2 mg/mL) and deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I; 0.05 mg/mL) in RPMI 1640 (Solarbio, China) with 10% FBS] and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. Digested tissue solution was passed through a 70-μm cell filter, and the filtrate was centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 min. The cells were resuspended in PBS for flow cytometry analysis17.

Flow cytometric analysis

For mouse splenocytes, CD4 as a surface marker, IL-17A, and Foxp3 as intramembrane and intranuclear staining cytokines, respectively, were required for the fixation and permeabilization of single-cell suspensions using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, USA). F4/80 and Ly6G were surface markers for mouse colon LP cells. Flow data were analyzed using FlowJo 10.9.0 software.

Histopathology analysis

Colons fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde were paraffin-embedded and sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm and stained with H&E and AB/PAS. H&E sections were scored according to the criteria (Supplementary Table 2). The total histologic score was calculated as the sum of all index scores. Tissue antigens were repaired using the microwave, left to cool naturally, and washed by shaking on a decolorizing shaker. Immunostaining was performed with anti-Muc2, anti-p-STAT3, anti-Th17, and anti-Foxp3 primary antibodies (1:500; Servicebio, China), followed by incubation with secondary antibodies (HRP, Goat Anti-Mouse IgG, 1:200; Servicebio, China) and then DAB color rendering. Next, cell nuclei were restained using hematoxylin and then dehydrated and sealed.

Immunofluorescence staining

Paraffin-embedded tissues were dewaxed and then hydrated. Tissue antigens were repaired using the microwave, left to cool naturally, and washed by shaking on a decolorizing shaker. Immunostaining was performed with anti-ZO-1, F4/80, and anti-occludin primary antibodies (1:500; Servicebio, China), followed by incubation with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488, Goat Anti-Mouse IgG, 1:400; Servicebio, China) and then DAPI staining of cell nuclei. Images were acquired using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti-SR, Japan).

Extraction and real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis of mouse colon RNA

Total RNA was extracted according to the procedure of trizol, and the RNA was reverse transcribed and amplified by PCR using Takara cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit and qPCR reagent, respectively, and the sequences of RT-qPCR primers are shown in Supplementary Table 3. The gene expression levels were normalized using GAPDH, and the relative quantification of gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and cytokines microarray assay

Distal colons (30 mg) were homogenized in PBS. The tissue solution was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min, and the supernatant was stored at −80 °C. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, inflammatory cytokines within the colon were determined using a commercial Elisa kit purchased from Fcmacs (Nanjing, China) or the Luminex Bio-Plex system. Protein levels were normalized to total protein concentration, which was determined according to the kit instructions from Beyotime (Shanghai, China).

Western Blot analysis

Proteins (30 μg/lane) were separated by 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS/PAGE) (NCM Biotech, Suzhou, China) and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, United States). After blocking for 20 min by adding a rapid blocking solution (Epizyme, Shanghai, China), the PVDF membrane was incubated overnight at 4 °C with dilutions of primary antibodies (STAT3, p-STAT3, β-actin) (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, United States). Secondary antibodies against HRP-conjugated rabbit or mouse IgG (1:1000; Beyotime, Shanghai, China) were added for 2 hours at 37 °C. Under the condition of avoiding light, about 1 mL of BeyoECL Plus (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was added to the surface of the bands. The bands were placed under a chemiluminescent gel imaging system (Bio-Rad, United States) for exposure and development. Gray scale values of the target protein strips were analyzed using Image J software.

SCFAs quantitative analysis

As previously described, gas chromatography was used to detect cecal SCFAs50. About 100 mg of feces were weighed, and 10 times saline and steel beads were added. After homogenization for 1 min using a high-speed tissue grinder (Servicebio, Wuhan, China), the sample was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was passed through a 0.22 μm aqueous filter tip. Next, 0.7 mL of filtrate was pipetted into a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube, and 0.2 mL of 10% sulfuric acid was added for 1 min, then 0.4 mL of anhydrous ether was added and mixed and then left to stand for 2 min, then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 2 min. The supernatant was passed through a 0.22 μm organic filter tip. The SCFAs were quantified by gas chromatography, and the content of SCFAs in the sample was calculated by an external standard method.

Fecal genomic DNA extraction and 16S-rRNA sequencing

Bacterial DNA was extracted from mouse feces using an OMEGA Soil DNA Kit extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, USA). The quantity and quality of extracted DNAs were measured using a Nanodrop NC2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis, respectively. The V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using (338 F 5′-barcode-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′ and 806 R 5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-barcode-3′) PCR. After the individual quantification step, amplicons were pooled in equal amounts, and pair-end 2*250 bp sequencing was performed using the Illumina NovaSeq platform with NovaSeq 6000 SP Reagent Kit (500 cycles). Microbiome bioinformatics were performed with QIIME2 2022.11. The DADA2 plug-in was used for quality filtering, de-noising, splicing, and chimera removal. The sequences obtained above were merged according to 100% sequence similarity, and the characteristic sequence ASVs and abundance data tables were generated. The Greengenes reference (v13.8) database was used for assigning taxonomy.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9.5 was used for plotting and statistical analysis, and data were expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was analyzed using Student’s t-test between two groups and one-way or two-way ANOVA between three groups following Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test for post-hoc analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 represented different statistical significances, ns stands for not significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses