Bridging the gap: examining circadian biology and fatigue alongside work schedules

Introduction

The introduction of artificial electric lighting in the 19th century and the restructuring of working times has progressively led to a departure from our usual 24-hour cycles, which respond to the alternating light-dark environment. Society is increasingly dependent on 24-hour, seven-days-a-week operations (the so-called “24/7 society”) that necessarily require either or both night- or rotating-shifts work. Many industries and services rely on a continuous workforce, including energy production, product manufacturing, transportation, health care, and law enforcement1.

In addition to the adverse effects of long working hours, exposure to nighttime light, and psychosocial factors, the health consequences of shiftwork must first be understood in terms of a fundamental desynchronization between the circadian rhythm of the endogenous biological clock and external synchronizers, the primary one being sunlight. The short-term consequences of shiftwork and nocturnal work are related to an increase in errors at home or in the workplace, leading to an increased risk of incidents and accidents. Some studies conducted in organizations in the United States, France, and the United Kingdom show that the number of workplace accidents related to sleep-related problems can vary from 10 to 30% of the total2. Furthermore, it has been shown that 17 h of continuous wakefulness has the same effect on the level of reaction as having a blood alcohol level above 0.5 g/l, the legal limit for non-professional drivers in many countries3. In the long term, it increases the risk of suffering from various chronic, complex and multifactorial diseases, including cardiovascular, metabolic, neurodegenerative, oncological, immune and mental pathologies, among others4.

It has been estimated that approximately 20% of the workforce in industrialized countries is employed in a job requiring rotating shifts work. Although the actual prevalence of clinically significant sleep disorders and excessive daytime sleepiness is unknown, it is estimated to affect between 2 and 5% of the general population. Studies have found a higher prevalence of sleep disorders in shift workers compared to non-shift workers5,6. Moreover, the prevalence of shiftwork disorder among rotating and night shift workers has been estimated to be between 10 and 38%. However, these figures do not include early morning or split-shift workers, who may be considered as at-risk groups as well7.

Companies working in the energy sector must operate continuously 24 h a day, 365 days a year, leading workers to the development of fatigue, a complex physiological state characterized by decreased attention and reduced mental and physical performance, and often accompanied by drowsiness, which can frequently trigger incidents and/or accidents8. Additionally, oil companies typically organize their operations using specific schedules, commonly employing 12-hour shifts that rotate between night and day. The second edition of the “Recommended Practice 755: Fatigue Risk Management Systems for Personnel in the Refining and Petrochemical Industries” (RP755) developed by the American Petroleum Institute (API) allowed work sets of up to 92 h with rest breaks of 34 h for 12 h shifts during normal operations9. This not only entails long working hours but also specific shift conditions. Studies in the petrochemical industry, which utilized subjective sleep measures, demonstrated both reduced sleep duration and quality among workers on 12-hour shift schedules8,10; while better sleep quality and cognitive performance were observed among individuals that worked for seven consecutive nights compared to those who worked four consecutive night shifts11. In the manufacturing industry, sleep deprivation was found to affect workers on 12-hour shifts and permanent night shifts, with reduced sleep quality particularly noted in the latter group12, consistent with findings from other studies13. Additionally, fast rotation shifts among nurses were associated with higher rates of shift work disorder14 and a greater impairment of perceptual and motor ability at the end of a night shift15.

All of these studies highlight the need for research in naturalistic settings to address how to improve the organization of night and shift schedules16. Our study combines objective and subjective data from workers in the logistics chain of an oil company in Argentina in a naturalistic environment, with the aim of evaluating the relationship between the specific design of work shifts and sleep patterns, perceived fatigue, circadian disruption, and psycho-affective variables. We compared two rotating-shift work schedules, the “2 x 2 x 4” fast rotating shift, and the “4 x 4 x 4” shift, with a non-rotating “fixed 12 h” schedule. To our knowledge, these specific shifts have not been analyzed in the petrochemical industry, which has rather focused on broader categories of shift work (e.g., seven days/seven nights, fixed-day, or fixed-night). Our analysis provides valuable insights for the design of safer and healthier work schedules, with the potential to enhance worker well-being and overall productivity.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

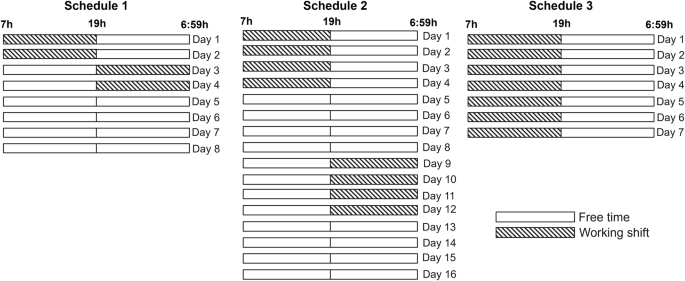

This was an observational, analytical, and cross-sectional exploratory study conducted between March 2021 and September 2023. It was conducted in a sample of 44 male shift-workers from an oil company in Argentina, who performed their work in three different schedules, which are detailed in Fig. 1. The three work schedules differ in the distribution of 12 h extended work shifts and free days. In the “2 x 2 x 4” schedule, workers completed two days of 12 h of daytime shifts followed by two consecutive 12 h night shifts, followed by four work-free days. In the “4 x 4 x 4” schedule, workers alternated four consecutive 12 h daytime shifts and four consecutive 12 h night shifts, flanked by four work-free days. Last, in the “fixed 12 h” schedule, workers did continuous 12 h diurnal work shifts during 40 days, without rest days between and after the 40 days of work. In this schedule, workers accumulate worked weekends as “extra workdays,” which can be taken later as days off. This schedule corresponded with the periods in which the plants were shut down for maintenance. All the schedules involved residential work.

Schedule 1: “2 x 2 x 4” schedule alternated two 12 h diurnal work shifts, two 12 h nocturnal work shifts and four free-days. Schedule 2: “4 x 4 x 4” schedule alternated four 12 h diurnal work shifts, four free-days, four 12 h nocturnal work shifts and four free-days. Schedule 3: “Fixed 12 h” schedule consisted of 12 h diurnal extended work shifts without resting days.

All subjects received detailed information about the procedures and gave written informed consent to participate before the study. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments and was approved by the review board of the Universidad Nacional de Quilmes.

Questionnaires

Questionnaires were completed by participants on an online platform developed for this study. Demographic data, and work, fatigue, alertness and performance characteristics were collected. Overweight was defined as BMI ≥ 25, and obesity as BMI ≥ 30. Participants reported the distance to work from their homes, and whether they had a secondary job. They also were asked about coffee and mate consumption. Mate is a traditional South American caffeinated beverage made from steeping dried leaves of the yerba mate plant in hot water.

Insomnia was evaluated through the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). It consists of seven items that inquire about the severity of sleep onset, sleep maintenance, early morning awakenings, sleep dissatisfaction, interference with daily functioning, noticeability of impairment attributed to sleep difficulties, and distress caused by sleep problems. Each item is rated on a scale from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater severity. The total score ranges from 0 to 28, with higher scores indicating more severe insomnia. Scores are interpreted as follows: no insomnia (0–7); sub-threshold insomnia (8–14); moderate insomnia (15–21); and severe insomnia (22–28)17.

Sleep apnea was assessed using the STOP-BANG index. It comprises eight yes-or-no questions, targeting the following risk factors associated with sleep apnea: tiredness, observed apnea, high blood pressure, elevated BMI, age, neck circumference, and gender. The total score ranges from 0 to 8, with a low risk indicated by scores of 0–2, intermediate risk by scores of 3–4, and high risk by scores of 5 or higher18.

The Spanish validated version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) was used to measure daytime somnolence. An ESS score between 11 and 14 indicates mild daytime sleepiness, a score between 15 and 17 indicates moderate daytime sleepiness, while a score higher than 18 indicates excessive daytime sleepiness symptoms19.

Participants also completed the number of days in which they experienced significant tiredness in the last month and the impact of fatigue in their usual activities in the last year. In addition, they reported their levels of alertness during their work tasks at the beginning, middle or end of the shift, both for during diurnal and nocturnal shifts, over the past month. Responses were recorded using an ad-hoc designed five-point Likert scale (from “not at all”, “poorly”, “somewhat”, “fairly”, and “very” rested and alert).

Psycho-affective variables were studied using Spanish validated versions of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). The BAI is a screening measure of frequency and intensity of anxiety symptoms that contains 21 items on a 4-point Likert scale, with 0 representing ‘not at all’ and 3 being ‘severely’. Scores of 0–7 are considered “minimal anxiety”; 8–15 are “mild anxiety”; 16–25 are “moderate anxiety”; and 26–63 are “severe anxiety”20. The BDI-II21 is a widely used self-report questionnaire to evaluate depression symptoms, that contains 21 items with a 4‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely). The inventory classifies symptom severity in four categories: minimal (0–13 pts), mild (14–19 pts), moderate (20–28 pts) or severe (29–63 pts) depression22.

Actimetry and temperature recordings

The sleep-wake cycle was studied using the ActTrust wrist accelerometers (Condor Instruments, Sao Paulo, Brazil), a previously validated device23,24. Participants were asked to wear the devices in the nondominant wrist and to complete sleep logs during at least 15 consecutive days. Sleep logs helped us to visually identify “in bed” episodes in actigraphic recordings. Actigraphy data was analyzed using ActStudio software (Condor Instruments, Sao Paulo, Brazil). The first sleep period after a nocturnal working day was considered as the main sleep period of that day. Other sleep periods starting between 8AM and 7PM and ending before 9PM were considered as naps. The following variables were reported: mean nocturnal sleep between diurnal workdays, mean diurnal sleep after nocturnal workdays, mean nocturnal sleep on free-days, mean total nap duration and mean duration of naps between nocturnal shifts.

Midtime of sleep during free days was computed as a proxy for estimating workers’ chronotype25,26. For this calculation, we exclusively utilized sleep data from the final two days of the free period since we assume that at that point the sleep debt has already been recovered. Additionally, we computed midsleep times for the nights between diurnal workdays using data from all three nights in between working shifts. As the “fixed 12 hour” schedule did not have free days during the studied period, the midtime of sleep was only calculated for the other two schedules.

The sleep regularity index (SRI) was calculated through the formula described by Philips et al. SRI was only calculated for participants with at least eight complete consecutive days of sleep recordings27,28. The index represents a measure of the probability (not the probability itself) of a participant being in the same sleep or wake state at two time-points 24 h apart, and can take values that vary from −100 to 100: a person who falls asleep and wakes up precisely at the same times every day will have an SRI of 100; a person who can be asleep or awake randomly throughout days will score 0; finally, in an infrequent albeit possible scenario for our participants, continuous periods of wakefulness (or, theoretically, of sleep as well) of over 24 h could generate negative SRI values28.

The wrist temperature signal was acquired using the Condor actigraphic devices, with sampling conducted every minute. Values below 25 °C were considered as NA. A maximum of 20% missing values and 6 h contiguous missing values were tolerated. Missing values were substituted using linear interpolation. A 60 min filter was then applied to the dataset. Finally, a cosinor model featuring a 24 h main rhythm and a 12 h harmonic was applied to the data. We reported the amplitude of each rhythm and the rhythm strength (percentage of the total variance explained by the model)29,30.

Data analysis

Numerical variables in the descriptive analysis are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as percentage and frequencies (%). For categorical values, differences between groups were assessed using chi-square. For numerical variables, with exception of midtime of sleep during free days, differences between groups were compared by means of a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post-hoc test. For midtime of sleep during free days, differences between “2 x 2 x 4” and “4 x 4 x 4” schedules were assessed using an independent samples t-test.

Finally, for “2 x 2 x 4” and “4 x 4 x 4” schedules we used a mixed-effects linear model to evaluate sleep variations within and between schedules, including sleep duration or midsleep as dependent variables, subject as a random factor and schedule, time of day and type of day as fixed factors.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics and habits are shown in Table 1. The sample consisted of 44 male shift-workers: 18 under the “2 x 2 x 4” scheme, 15 under the “4 x 4 x 4” scheme and 11 under the “fixed 12 h” scheme (Fig. 1). Groups did not differ significantly in age, the frequency of overweight, obesity, physical activity, or caffeinated drinks consumption.

Workers under “4 x 4 x 4” schedule had longer commute times compared to workers under “2 x 2 x 4” and “fixed 12 h” schedules (commute times main effect: p < 0.001; post-hoc test: p < 0.001 for “4 x 4 x 4” schedule vs. “2 x 2 x 4” schedule and p < 0.001 for “4 x 4 x 4” schedule vs. “fixed 12 h” schedule). Additionally, a higher percentage of workers on “4 x 4 x 4” schedule reported holding a secondary job (p = 0.008) (Table 1).

Sleep characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 2. The mean duration of nocturnal sleep on workdays was 5 h:42 m for workers under the “2 x 2 x 4” schedule, 5 h:10 m for those under the “4 x 4 x 4” schedule, and 6 h:19 m for those under the “fixed 12 h” schedule. We found a significant main effect difference in nocturnal sleep between the analyzed schedules (p = 0.003). Specifically, nocturnal sleep duration for workers under the “4 x 4 x 4” schedule was more than an hour shorter than for workers under the “fixed 12 h” schedule (post-hoc test: p = 0.002) (Table 2).

We did not find differences in diurnal sleep after nocturnal shifts between participants under the “2 x 2 x 4” and the “4 x 4 x 4” schedules (“fixed 12 h” schedule does not include nocturnal workdays). Regarding sleep during free days, workers under the “4 x 4 x 4” schedule slept 30 min less than those under the “2 x 2 x 4” schedule (p = 0.041). We found that 73% of workers in the “2 x 2 x 4” schedule and 67% under the “4 x 4 x 4” schedule took naps before and between nocturnal workdays (p = ns), and we did not find differences in nap duration between schedules (Table 2).

Nocturnal sleep midsleep times on free days was similar between “2 x 2 x 4” and “4 x 4 x 4” schedules. We found significant differences for midsleep on diurnal workdays (p = 0.001). Particularly, midsleep for “4 x 4 x 4” schedule was significantly earlier than for “fixed 12 h” schedule (post-hoc test: p < 0.001). Regarding sleep regularity, we also found a significant main effect difference (p < 0.001). We determined a significantly lower SRI for workers under the “2 x 2 x 4” schedule compared to “4 x 4 x 4” and “fixed 12 h” schedules, and for workers under the “4 x 4 x 4” schedule compared to the “fixed 12 h” schedule (post-hoc test: p < 0.001 for all contrasts) (Table 2).

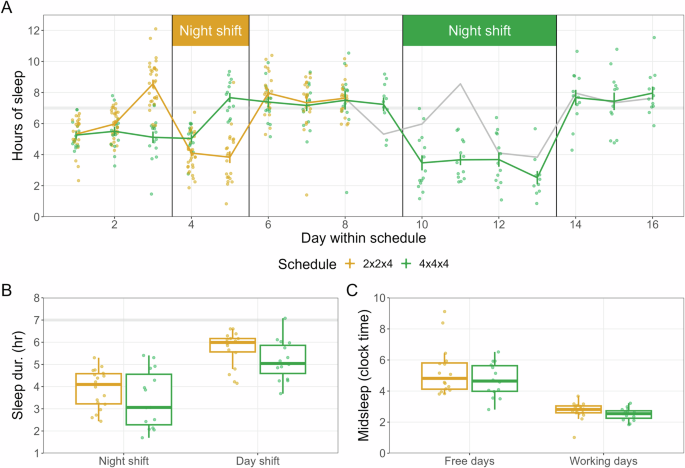

Figure 2A shows sleep duration across the “2 x 2 x 4” and “4 x 4 x 4” schedules. Sleep duration during the day after nocturnal work shifts was significantly shorter than sleep during the night between diurnal shifts for both schedules (Fig. 2B, “time of day” effect: p < 0.001). Also, midsleep was earlier on diurnal working days compared to free days for both schedules (Fig. 2C, “type of day” effect: p < 0.001).

A Mean ± SEM of sleep hours across different days within the schedule. For both schedules, day 1 represents the initial diurnal work shift. B Box plot comparing sleep hours between nocturnal and diurnal work shifts for both schedules (mixed-effects repeated measures linear model: “time of day” effect: p < 0.001). C Box plot of the midpoint of sleep (midsleep) during free days and diurnal work shifts for both schedules (mixed-effects repeated measures linear model: “type of day” effect: p < 0.001).

Finally, we did not find differences in diurnal sleepiness or sleep apnea risk between the schedules. However, we found significant differences on the Insomnia Severity Index (p = 0.017). Notably, workers under the “2 x 2 x 4” schedule showed higher scores than those under the “4 x 4 x 4” one (post-hoc test: p = 0.024) (Table 2).

Table 3 shows the results of the circadian temperature rhythm analysis. Sample sizes decreased for all groups due to the acceptance criteria for maximum NA values, which did not significantly differ between groups. Significant differences were observed for the 12 h amplitude of the temperature rhythm (p = 0.030; post-hoc: “fixed 12 h” > “2 x 2 x 4”, p = 0.023) and the percentage of variance explained by the model (p = 0.005; post-hoc: “fixed 12 h” > “2 x 2 x 4”, p = 0.004). For these two variables, the “4 x 4 x 4” schedule presented intermediate values between the “fixed 12 h” and “2 x 2 x 4” schedules (Table 3).

Fatigue impact, alertness and wellbeing are presented in Table 4. We found significant differences in the reported number of workdays with significant tiredness in the last month (p = 0.022). Workers under the “fixed 12 h” schedule reported a higher number of workdays with significant tiredness in the last month compared to those under the “4 x 4 x 4” schedule (post-hoc test: p = 0.019). However, it is important to note that the ‘fixed 12 h’ schedule involves more workdays per month compared to the other schedules. This resulted in the disappearance of significant differences when adjusting for the number of days worked, suggesting a potential correlation between increased workload and fatigue (data not shown). Additionally, when comparing the reported number of workdays with significant tiredness in the last month between the “2 x 2 x 4” and “4 x 4 x 4” schedules, the former reported a significantly higher number than the latter (p = 0.034). Workers under the “4 x 4 x 4” schedule reported being less negatively impacted by fatigue in their ability to learn new tasks (p = 0.009) and overall job satisfaction (p = 0.009) compared to workers under the “2 x 2 x 4” and “fixed 12 h” schedules; and in their relationships with coworkers (p = 0.017) compared to workers under the “fixed 12 h” schedule (Table 4).

We did not find differences between schedules in the reported levels of alertness in the middle of diurnal workdays, but workers under the “2x2x4” schedule reported lower levels of alertness in the middle of nocturnal work shifts compared to those under the “4x4x4” schedule (p = 0.028) (Table 4).

Finally, we noted significant differences in the Beck Depression Index scores (p = 0.005). Particularly, we found higher scores for depression symptoms for workers under the “2x2x4” and “fixed 12 h” schedules compared to those under the “4x4x4” schedule (p = 0.037 for “2x2x4” schedule vs. “4 x 4 x 4” schedule and p = 0.006 for “fixed 12 h” schedule vs. “4 x 4 x 4” schedule), while anxiety levels were similar (Table 4).

Discussion

The scheduling of shiftwork depends on several factors, including productivity, costs, and workers’ wellbeing. Indeed, shiftwork has emerged as one of the key translational opportunities for circadian research, together with a chronobiological approach to health issues. Among the different variables that can be optimized is the number of days under nocturnal or diurnal tasks and the rest periods between them. This is a complex issue that should take into account several variables, balancing productivity, presenteeism, accident and incident rates, health and the impact on the social life of workers31. Since there is a clear link between shift duration, sleep, and health outcomes32, and the effects of continuous sleep deprivation and irregularity is cumulative33, a correct decision in terms of the schedule might have long-lasting consequences. Indeed, many other variables contribute to both productivity and wellbeing during shiftwork, including environmental factors (i.e., illumination, feeding schedules, etc.), individual characteristics such as chronotype and even commuting time and distance, and the nature of the work being performed, as well as stress and inherent working hazards. Since shiftwork also affects mood vulnerability29,34, it is not surprising that such routine impacts both co-workers and their family relationships.

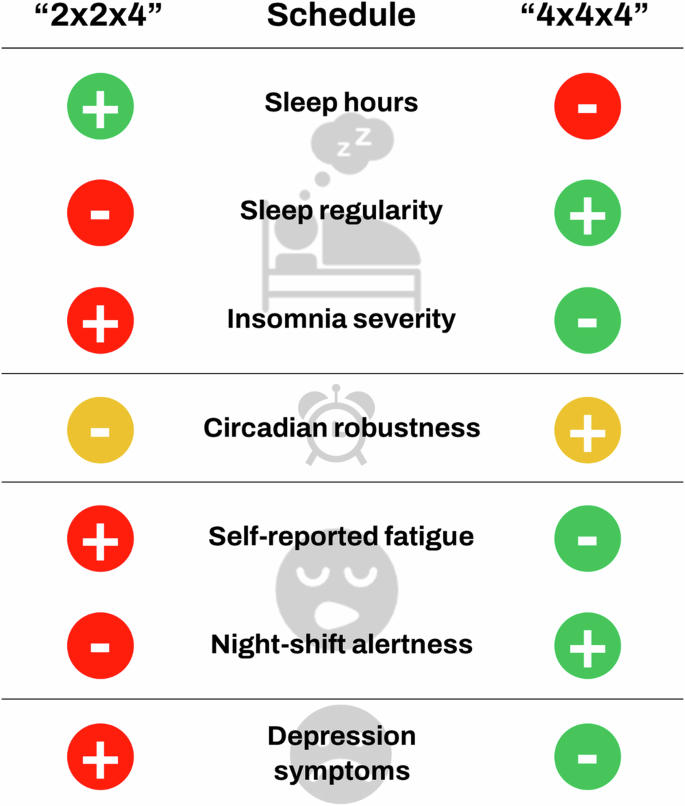

Here we examined, combining objective and subjective measurements, the effect of three different working schedules on the sleep-wake cycle, temperature rhythm and perceived performance of workers in the logistics branch of one of the biggest oil companies in South America. In all cases, the duration of sleep during the resting period was significantly less than the recommended 7 h of nocturnal sleep10. The “2 x 2 x 4” schedule showed increased nocturnal sleep time after diurnal work, decreased sleep regularity and a dampened circadian temperature rhythm. Additionally, this shift exhibited higher levels of insomnia, increased fatigue impact, lower alertness levels, and heightened symptoms of depression (Fig. 3).

The “2 x 2 x 4” schedule showed increased nocturnal sleep time after diurnal work, decreased sleep regularity and higher levels of insomnia. Additionally, this shift exhibited increased fatigue impact, lower alertness levels during the night shift, and heightened symptoms of depression. The “2 x 2 x 4” schedule exhibited lower circadian robustness only when compared to the “fixed 12 h schedule”. However, the “4x4x4” schedule did not significantly differentiate from either of the other groups.

Participants in our study only worked 12 h shifts. There is much discussion regarding their advantage over 8 h shifts; including an increased sleep opportunity during rest days. However, some reports state that this schedule might decrease alertness35 and deteriorate domestic life36. While there is a clear consensus in the fact that any shiftwork schedule will result in circadian and sleep disruption, especially at the extremes of very long or very short types of rotation, there is no clear effect of switching between 8- and 12 h shifts37. Since oil industry must rely on 24/7 activities, the most usual schedule in companies around the world involves 12 h shifts for 2 or 4 consecutive days (in contrast to the previously implemented 8-h shifts system, with less frequent rotation). However, long work hours are associated with short sleep duration, sleep disruption, and decreased alertness35,38,39. The impact of shiftwork schedules in the oil industry on the domestic and social life of workers has also been highlighted elsewhere40.

The disruption of sleep patterns and circadian temperature rhythms observed in workers under the “2 x 2 x 4” scheme may probably be attributed to the shorter duration of shifts. Sleep regularity, a measure of the consistency of day-to-day variability in sleep–wake timing,has recently received much attention, in terms of its importance for health, safety and productivity. One might expect that alternating between four days of nocturnal sleep and four days of diurnal sleep would negatively impact sleep regularity more than alternating between six days of diurnal sleep and two days of nocturnal sleep. However, our findings indicate the opposite. It is known that fluctuations in both environmental and behavioral factors associated with variability in sleep timing can induce circadian disruption41 and, in turn, sleep disturbances4. In this regard, the increased sleep duration observed in this group could be explained as a compensatory mechanism for the disruption of circadian rhythms. While extending sleep on non-work days is a common human pattern to counter sleep deficiency on work days41, this practice may not be sufficient in the “2 x 2 x 4” schedule, resulting in additional sleep during work days. Indeed, in a previous study involving long-haul bus drivers working with a two-up operations system, we reported that workers under high fatigue risk working schedules showed increased sleep duration during the trips on the bus30.

The results obtained from the circadian analysis of temperature reinforce what has been discussed so far. The “2 x 2 x 4” schedule exhibited lower circadian robustness compared to the “fixed 12 hour” schedule, while the “4 x 4 x 4” schedule showed intermediate values, without significantly differentiating from the other groups. Taken together, this reveals a greater circadian disruption in the “2 x 2 x 4” schedule compared to the “4 x 4 x 4” one. These results are also consistent with the disruption of the expression of the circadian rhythm of wrist temperature by shift-work reported by our group in drivers exposed to high-risk working schedules30 and by others41,42,43.

In our work, we observed that workers from the “2 x 2 x 4” schedule reported a higher number of days with significant tiredness in the last month, a greater negative impact of fatigue on their daily activities, and more depression symptoms. Also, these workers reported lower levels of alertness in the middle of night shifts than workers from the “4 x 4 x 4” schedule. This aligns with the circadian disruption observed in this group, known to potentially result in sleep disturbances, sleep medication consumption, persistent fatigue and mood disorders, and/or burn out, which could compromise safety and health. In fact, a report from the 1990s44 investigated oil refinery workers during their night shift, finding significant changes in endocrine rhythms, with a lower amplitude for cortisol and higher peaks for melatonin. It is also well-known that the number of years spent on shiftwork in this industry further affects sleep, health, and productivity45,46. More recently, studies have demonstrated that impaired sleep quality and shorter sleep duration in oil activity shift workers are associated with increased fatigue-related incidents8.

We also considered chronotype, which might affect the outcome of shift workers, with certain advantages for late-types47. In our case, we did not find significant differences in midsleep on free days between Schedules “2 x 2 x 4” and “4 x 4 x 4”. The midpoint of sleep on free days for “2 x 2 x 4” schedule was at 05:22 am, while for “4 x 4 x 4” schedule it was at 04:50 am, both corresponding to slightly late chronotypes48; however, it should be noted that the Argentinian is a particularly late culture. Since the alignment of individual chronotype with working hours might reduce circadian disruption49, more data is needed to assess the impact of this variable on performance and wellness in this particular industry.

This study has some limitations that must be taken into account. There are several confounding factors that should be considered, and were not addressed here, to fully understand the impact of shift work design on sleep, alertness and fatigue. Among these are the nature of tasks performed, the environmental conditions both at work and at home, and the types of jobs. Moreover, since all the subjective measures were retrospective, it is possible that worker recall after some time may have been less reliable.

According to the guiding principles of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society (2021)50, the duration of working shifts is linked to adverse performance, safety, and health outcomes, and several countermeasures are proposed to overcome such adverse consequences. The first of these measures is to “schedule interventions to maximize daily sleep opportunity, consistently align work with the biological drive for wakefulness and increase time for recovery after extended duties or multiple shifts.” Common sense dictates that working four consecutive nights would be worse for worker’s rest, circadian rhythms and wellbeing than shifting between two diurnal and two nocturnal workdays. However, our study directly compared three different shiftwork schedules for the oil industry, finding that a “2 x 2 x 4” shift work schedule showed decreased sleep regularity and a dampened circadian temperature rhythm, associated with higher levels of insomnia, increased fatigue impact, lower alertness levels, and heightened symptoms of depression. These findings underscore the complex interactions between shift schedules and worker health outcomes. We believe that our results contribute to a further understanding of the optimal working conditions that our 24/7 society demands to achieve improved outcomes in health, wellness, and productivity, representing a clear case for translational circadian research. By understanding the specific impacts of different schedules on sleep patterns and psychological health, employers can tailor shift rotations to mitigate negative effects. Future research should explore targeted interventions or adjustments to shift schedules aimed at further optimizing worker wellbeing and operational effectiveness.

Responses