AAV8-P301L tau expression confers age-related disruptions in sleep quantity and timing

Introduction

Tauopathies are a class of more than 20 neurodegenerative diseases characterized by the abnormal aggregation of the protein tau, which forms intraneuronal deposits and causes neuronal death1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Cognitive decline is the primary clinical symptom among tauopathies, and the clinical presentations can be notably heterogenous, highlighted by the differences between Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and frontotemporal dementias associated with chromosome 17 (FTD)8,9,10. However, time-of-day dependent sleep disturbances are reported in cases of both AD and FTD10,11,12,13,14,15. As sleep is essential for maintaining brain health, this commonality highlights the need to understand 24-h sleep rhythms in response to progressive neuropathological tau deposition.

Sleep symptoms in patients with tauopathy indicate that sleep timing is disrupted and inefficient, which causes daytime sleepiness, notably in the transition from morning to afternoon10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Sleep disturbances can diverge between patients with AD and FTD, and may present more severely in FTD10,13,14. To further study tauopathy-induced sleep disturbances, sleep has been characterized in the rTg4510 and PS19 tauopathy murine models, which carry distinct FTD-associated tau mutations and have neuronal dysfunction18,19,20. Sleep analysis using both electroencephalogram (EEGs) and the noninvasive PiezoSleep Mouse Behavioral Tracking System reveal clear age-related sleep disturbances in quantity and timing in response to the respective FTD-associated mutant tau overexpression and neuropathology21,22,23,24.

To support the growing body of literature on sleep disturbances in primary tauopathy and highlight the time-of-day specific changes in sleep, we assessed 24-h sleep behavior in AAV8-P301L tau expressing male and female mice. We discovered that AAV8-P301L tau expressing mice of both sexes have altered sleep timing and quantity after tau deposition appears in the model, aligning with other tauopathy murine models. Using a longitudinal experimental design approach we discovered that sleep timing architecture is strikingly altered with age in AAV8-P301L mice compared to controls, particularly at the onset of the active phase. The time-of-day specificity in our findings implicates inclusion of circadian-based assessments for pathological tau-induced sleep symptoms, and emphasizes the need for circadian considerations in tauopathy research.

Results

AAV8-P301L tau delivery results in loss of sleep during typical sleeping hours

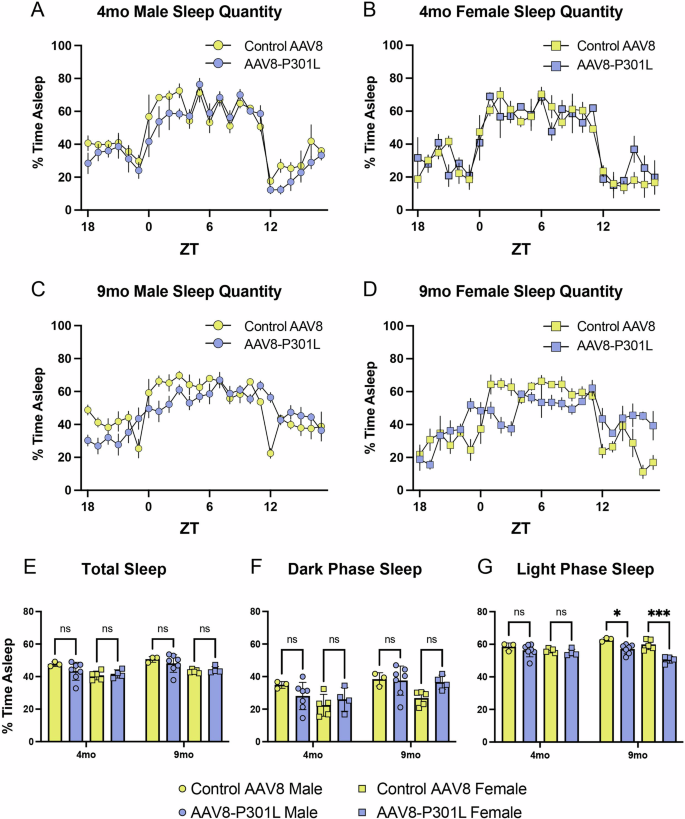

We have previously validated the tauopathy in the same AAV8-P301L mice used in this study25 and additionally confirm here that the AAV8-P301L mice express human tau in the brain (Supplementary Fig. 1). We also show histologically that the human tau is expressed in a widespread manner (Supplementary Fig. 2). Using these mice, we measured the percentage of every hour spent sleeping in AAV8-P301L tau expressing mice and their sex-and-age matched controls at 4 months (Fig. 1A, B) and then repeated the measures in the same cohort of mice at 9 months (Fig. 1C, D) of age. This longitudinal design allows for robust assessment of changes in gross sleep architecture throughout the day. Male and female AAV8-P301L tau expressing mice have normal gross sleep architecture at 4 months compared to sex-matched controls (Fig. 1A, B). Assessment again at 9 months of age, identified that the AAV8-P301L mice of both sexes had significantly different sleep timing and quantity compared to their sex-matched controls (Fig. 1C, D).

General sleep architecture is maintained in 4 month old male (A) and female (B) AAV8-P301L mice compared to their respective sex-matched controls. Sleep timing and quantity is altered at 9 months in AAV8-P301L mice (C, D). Average time sleeping throughout the entire day (E) or exclusively in the dark/active phase (F) is not significantly different. Sleep quantity is significantly reduced in 9 month old AAV8-P301L tau mice of both sexes compared to sex-matched controls in the light/rest phase (G). N = 4 female AAV8-P301L mice, N = 7 male AAV8-P301L mice, N = 5 female control AAV8 mice, N = 3 male control AAV8 mice; 2-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

When assessing the average percentage of time spent sleeping over the course of the entire 24-h day, no significant changes were apparent between AAV8-P301L and control AAV8 mice of either sex, at both 4 and 9 months of age (Fig. 1E). To determine if sleep quantity changes were specific to the time of day, we also assessed the average percentage of time spent sleeping in the 12-h active phase of the day (lights off) and the 12-h rest phase of the day (lights on). The percentage of time spent sleeping in the dark/active phase of the day was not significantly different between AAV8-P301L and control AAV8 mice at both 4 and 9 months (Fig. 1F). Interestingly, the percentage of time spent sleeping during the light/rest phase of the day was significantly reduced in the AAV8-P301L tau mice of both sexes at 9 months (Fig. 1G). This finding indicates that progression of the P301L tau pathology at 9 months of age is directly associated with reduced time spent sleeping in the normal rest phase.

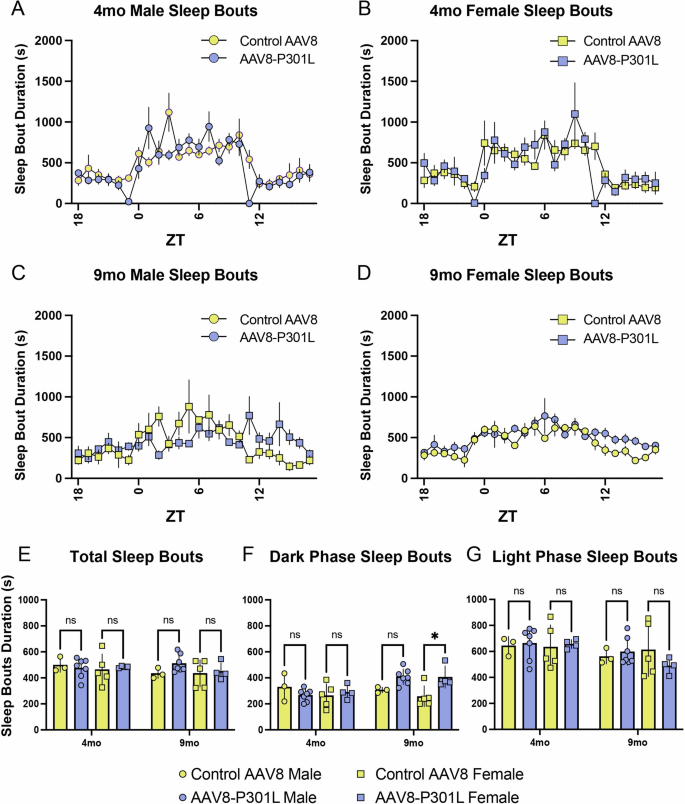

Female AAV8-P301L tau expressing mice have longer sleep bouts during normal wake hours

To further appreciate differences in sleep architecture in AAV8-P301L tau expressing mice, we analyzed the temporal pattern of sleep bout durations. Since mice sleep in a polycyclic manner and can experience more than 40 sleep episodes per hour, it is important to note that this data represents the duration of the sleep bouts and not the number of sleep bouts. We found that daily bout lengths in male and female AAV8-P301L tau expressing mice are generally maintained at both 4 (Fig. 2A, B) and 9 months (Fig. 2C, D) of age compared to sex-matched controls. We then assessed the average sleep bout duration from the entire 24-h day, the 12-h active phase (lights off), and the 12-h rest phase (lights on), to determine time of day specificity as we did with the percentage of time spent sleeping (Fig. 1). We did not find changes in average sleep bout durations over the 24-h day or in the light phase in AAV8-P301L tau expressing mice at either 4 or 9 months (Fig. 2E, G). Although unaltered in males at both ages and in females at 4 months of age, AAV8-P301L females had significantly longer sleep bouts at 9 months (Fig. 2F). This sex difference may indicate that clinical sleep symptoms diverge between sexes.

Daily sleep bout durations in 4 month (A, B) and 9 month (C, D) old AAV8-P301L tau and control AAV8 mice. Average sleep bout durations throughout the entire day (E) and in the light/rest phase (G) were not significantly altered, but sleep bout durations were significantly increased in the dark/active phase of 9mo AAV8-P301L tau expressing female mice (F). N = 4 female AAV8-P301L mice, N = 7 male AAV8-P301L mice, N = 5 female control AAV8 mice, N = 3 male control AAV8 mice; 2-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, *p < 0.05.

These findings suggest that the significant decrease in average sleep quantity during the light phase in 9-month-old AAV8-P301L mice of both sexes (Fig. 1G) is not explained by shorter sleep bouts in the light phase, and may instead be due to altered frequency of shorter or longer sleep bouts. To further examine how sleep bouts contribute to the average sleep time, we analyzed the frequency distribution of sleep bouts of varying durations.

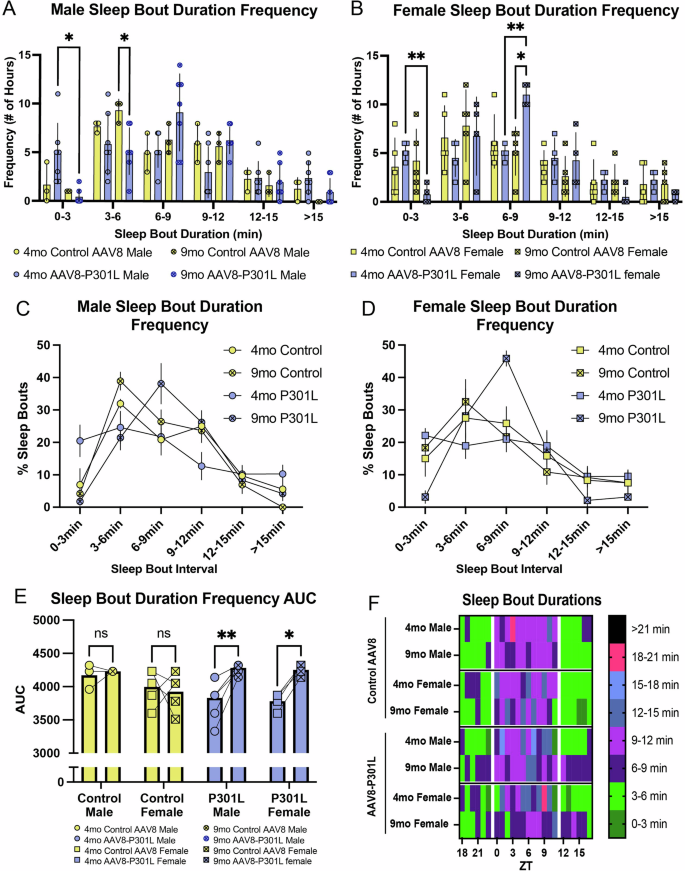

Sleep bout durations change frequency in AAV8-P301L tau expressing mice

The frequencies of specified sleep bout durations were evaluated to further describe the altered sleep architecture in AAV8-P301L tau expressing mice. We evaluated the frequency of sleep bout durations in 3-minute bins of 4 and 9 month old AAV8-P301L and control AAV8 male (Fig. 3A) and female (Fig. 3B) mice. We discovered that AAV8-P301L males, but not females, experience significantly fewer sleep bouts lasting 3–6 min at 9 months of age compared to their respective sex-matched 9-month-old control AAV8 mice (Fig. 3A, B), indicating another sex-specific divergence in tauopathy sleep symptoms. However, 9-month-old AAV8-P301L females experienced significantly more sleep bouts lasting 6–9 min compared to their age and sex-matched control AAV8 mice (Fig. 3B). This was also significantly greater than the bout frequency of 6–9 min sleep bouts from the same AAV8-P301L females 5 months prior, at 4 months of age (Fig. 3B). Another age-related changes was that the frequency of 0–3 min lasting sleep bouts significantly decreased from 4 to 9 months in both AAV8-P301L male and females (Fig. 3A, B).

The number of hours with mean sleep bout durations ranging from 0–3 min is significantly reduced as AAV8-P301L tau expressing mice of both sexes age from 4 to 9 months (A, B). Sleep bouts ranging from 3–6 min lose frequency in AAV8-P301L males (A). Female AAV8-P301L tau mice experience significantly more sleep bouts ranging from 6–9 min (B). Group mean sleep bout duration histograms (C, D) and sleep bout duration compositions (area under the curve of the sleep bout duration histogram for individual mice) are significantly altered in AAV8-P301L mice as they age from 4 to 9 months (E). Summary of sleep bout findings (F). N = 4 female AAV8-P301L mice, N = 7 male AAV8-P301L mice, N = 5 female control AAV8 mice, N = 3 male control AAV8 mice. A-B; 2-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. D; 2-Way ANOVA with Šidák multiple comparison test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

We then assessed the percentage of sleep bouts in each 3-minute binned duration for a given group to determine how much representation each sleep bout duration had over the 24-h day. The duration frequency curves for both male and female mice (Fig. 3C, D) indicate an increased frequency of 6–9 min sleep bouts in AAV8-P301L mice at 9 months of age. Figures 3C, D represent the duration frequencies of the group, but this analysis was done on individual mice to acquire the area under the curve (AUC). The 9-month AAV8-P301L mice had larger AUC values as they aged from 4–9 months (Fig. 3E), indicating that their sleep bout duration composition was 1) distinct and 2) showed preference for one bin of sleep bout length (notably 6–9 min) as they aged. The AUC values of AAV8-P301L mice from 4 to 9 months also suggest that their sleep timing distinctly changes with age compared to controls. Figure 3F summarizes the sleep bout distinctions and emphasizes that the age-related changes in sleep bout durations observed in AAV8-P301L mice notably deviate from age-related changes in controls. Since the age-related sleep bout changes in AAV8-P301L mice were divergent from controls, we were motivated to further analyze how tauopathy progressively impacts sleep symptoms in the same mouse with age.

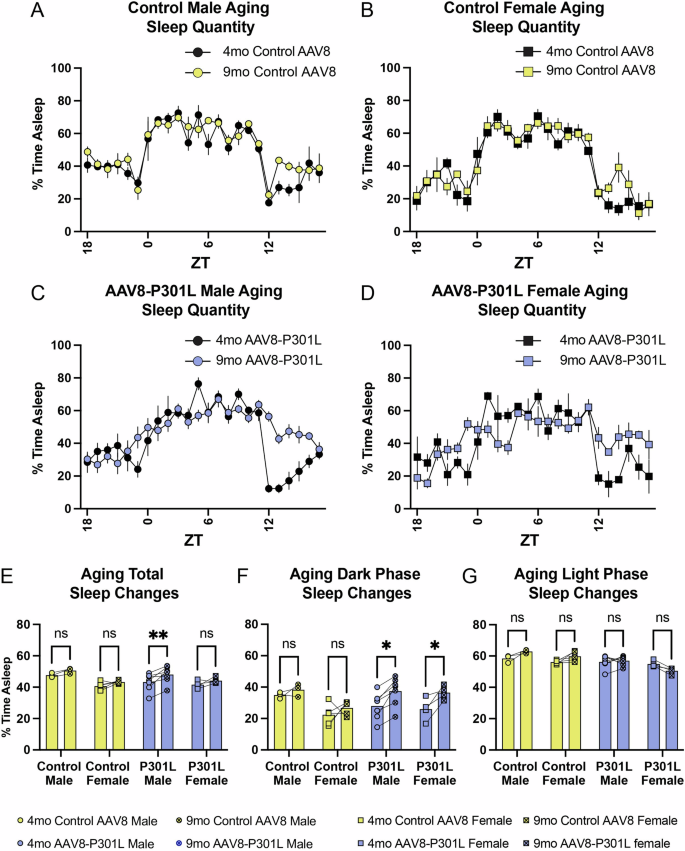

Persistent AAV8-P301L expression with age gives rise to increases in sleep during the typical wake phase and is exacerbated at the onset of the wake phase

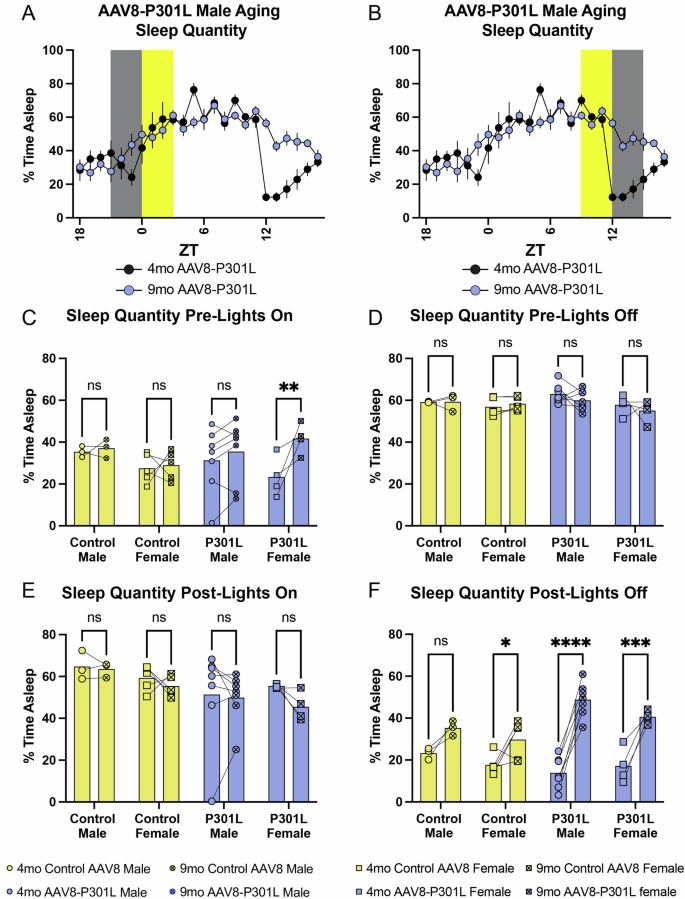

The age-related changes observed in sleep bout duration frequency motivated an analysis of the age-related changes in the average percentage of time spent asleep. General sleep architecture is maintained in control AAV8 mice as they aged from 4 to 9 months (Fig. 4A, B). This consistency was not apparent in the AAV8-P301L tau expressing mice of both sexes with age (Fig. 4C, D). The average percentage of time spent sleeping over the entire 24 h day was not different in control AAV8 mice as they aged from 4 to 9 months, as expected (Fig. 4E). This was significantly increased in AAV8-P301L males but not in AAV8-P301L females (Fig. 4E), representing another divergent sex-specific sleep disturbance with tauopathy. Again, we analyzed the average percentage of time spent sleeping in the 12-h active phase of the day (lights off) and the 12-h rest phase of the day (lights on) to determine time of day specificity to age-related changes in tauopathy. The average percentage of time asleep was significantly increased in AAV8-P301L mice of both sexes in the dark/active phase as they aged from 4 to 9 months (Fig. 4F), indicating increased sleep during typical murine wake hours. Sleep quantity was unchanged with age in the light/rest phase (Fig. 4G).

AAV8-P301L tau mice show clear and exacerbated alterations in sleep quantity after a 5 month aging period compared to control AAV8 mice (A–D). AAV8-P301L males sleep significantly more from 4 to 9 months throughout the entire day (E). AAV8-P301L mice of both sexes sleep significantly more during the dark/active phase as they age, without significant changes in the light/rest phase (F, G). N = 4 female AAV8-P301L mice, N = 7 male AAV8-P301L mice, N = 5 female control AAV8 mice, N = 3 male control AAV8 mice; 2-Way ANOVA with Šidák multiple comparison test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

The increased sleep quantity with age in AAV8-P301L mice of both sexes during typical wake hours (dark phase) was also relative to the zeitgeber (light) transition. The distinctions from 4 to 9 months in average time spent sleeping per hour in AAV8-P301L mice were visually clear in the line graph of their general sleep architecture (Fig. 4C, D). Figures 5A, B are representative sleep tracings that indicate the windows of time (3-h windows) surrounding the transition from lights off-to-on (Fig. 5A) and lights-on-to-off (Fig. 5B). We assessed sleep quantity between control AAV8 and AAV8-P301L mice of the same age and did not find significant changes in these time frames (Supplemental Fig. 3). Therefore, we continued to assess the same mice as they aged from 4 to 9 months. During the 3-h of the dark phase leading up to the lights turning on, no changes were observed in control mice of both sexes as they aged from 4 to 9 months. While we did not observe age-related changes in AAV8-P301L males during this 3-h window, the female AAV8-P301L tau expressing mice slept significantly more in the 3 h leading up to the light/rest phase as they aged (Fig. 5C). We did not observe any age-related changes in average time spent sleeping in either control AAV8 or AAV8-P301L mice of either sex in the 3-h following the lights turning on (Fig. 5E) or in the final 3-h of the light phase leading into the dark phase (Fig. 5D). However, during the first 3-h after the lights turned off (beginning of the dark phase), we found notable changes in average time spent sleeping (Fig. 5F). We observed a nonsignificant increase in male control AAV8 mice and a significant age related increase in female control AAV8 mice during the first 3-h of the dark phase. The 9-month-old control males slept ~1.5x more during the dark phase onset compared to their sleep quantities at 4 months. The control AAV8 females slept ~1.6x more at 9 months compared to what they slept at 4 months of age. We observed a notable significant increase in AAV8-P301L mice of both sexes during the first 3-h of the dark phase. The AAV8-P301L males slept ~3.5x more on average during the 3-h dark phase onset at 9 months compared to how long they slept at 4 months of age. The females slept ~2.3x more at 9 months compared to their average time spent sleeping at 4 months (Fig. 5F).

Representative indications of the 3-h windows pre-and-post the rest and active phases (A, B). AAV8-P301L tau expressing females sleep more at the onset of the light/rest phase with age (C), but no significant changes occur in the first 3 h of the light/rest phase (E) or the last 3 h of the light/rest phase with age (D). AAV8-P301L mice of both sexes sleep significantly more with age at the onset of the dark/active phase (~2.36x more in females and ~3.51x more in males from 4 to 9 months). Control AAV8 females slept significantly more with age to a lesser extent (~1.68x more) but comparable to the statistically insignificant increase in males (~1.51x more) (F). N = 4 female AAV8-P301L mice, N = 7 male AAV8-P301L mice, N = 5 female control AAV8 mice, N = 3 male control AAV8 mice; 2-Way ANOVA with Šidák multiple comparison test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Discussion

We assessed sleep quantity and timing longitudinally at two ages in the AAV8-P301L tauopathy model and identified sleep disturbances at 9 months of age. Our findings align with reported sleep disturbances in patients with frontotemporal dementias10,11,12,14,17 and preclinical transgenic tauopathy murine models21,22,24,26. In addition to elucidating changes in sleep architecture with tauopathy, this study also included assessment of sex-specific changes in sleep phenotypes AAV8-P301L mice. We discovered sex-specific disturbances in sleep quantity and timing, suggesting sex can influence tauopathy sleep symptoms. For example, we see baseline insignificant mean differences between sexes in our 9-month-old controls at the sleep-wake transition, which may underlie why males have a larger sleep quantity increase during their sleep-wake transition (Fig. 5F) when AAV8-P301L tau is introduced. This should be explored further, as sex-specificity in tauopathy sleep disturbances could have a considerable translational impact.

These data also reveal that P301L tau deposition influences age-related changes in sleep timing distinctly from the normal changes observed in control mice. We show that from 4-to-9 months, which captures pathological neuronal tau aggregate accumulation in the model at 6 months1, the AAV8-P301L tauopathy mice sleep remarkably more at the onset of the active phase. This finding suggests that the 3-h window at the onset of the dark/wake phase is robustly sensitive to tauopathy-related changes in sleep behaviors in both sexes. The exacerbated increase in sleep quantity during this specific time frame may serve as a translational indicator for neuronal tau deposition with age.

Compared to their sex-matched controls, AAV8-P301L mice sleep less during the light/rest phase at 9 months of age (Fig. 1G) and may sleep more at the onset of the dark/wake phase as they age (Fig. 5F) in order to compensate. AAV8-P301L mice also have longer average sleep bouts during the light-to-dark transition (Fig. 2C, D), but it is unclear if our findings represent an increased need for sleep manifested by the biological promotion for sleep, or an inability to efficiently transition into wake. Therefore, additional studies to elucidate the biological bases of this finding are warranted. This may be due to changes in either wake or sleep-promoting neurotransmitter generation and the expression of their respective receptors. Since cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) level of the wake-initiating neuropeptide orexin-A is associated with CSF phosphorylated tau in cognitively normal elderly individuals27, tau deposits may impact this relationship. The persistence and distribution of orexin may also be altered in the AAV8-P301L model and underlie the inability to properly transition into the wake-phase. Decreased orexin-1 receptor gene expression has been reported in the rTg4510 mouse model28. It is known that the two orexin receptor subtypes are widely expressed29,30, particularly in the hippocampus, where tau deposition is persistent in the AAV8-P301L model1,25. Notably, activation of orexin neurons are controlled by the suprachiasmatic nucleus clock (SCN)30,31,32, which may underlie specific time-of-day changes in sleep behaviors and inability to transition into wake phases.

Beyond circadian-controlled activation of orexin neurons, the core circadian clock is also impacted in murine tauopathy models. The PS19 model, which has dysregulated sleep timing and quantity with age21,24, has increased expression of core clock genes Bmal1 and Per2 in the SCN at ZT1433, which is within the 3-h onset of the dark phase. Although the models are distinct, this aligns with the exacerbated increased average time spent asleep in the AAV8-P301L mice as they age (Fig. 5F). In addition to the SCN, altered expression of Bmal1 and Per2 are apparent in the hippocampus as well. ZT14 was also the peak time for soluble tau protein detection in the hippocampus of PS19 mice33. Another model with circadian perturbations is the rTg4510 model, which has its own altered sleep phenotypes22,28. These mice have longer free running periods in the total darkness, supporting a disrupted central circadian clock34. rTg4510 mice had altered Per1 protein levels in the hypothalamus compared to non-transgenic controls, but normal Bmal1 protein levels. The Bmal1 and Per2 temporally regulated protein levels were both altered in the hippocampus. Importantly, pathological tau deposition was noted in both hypothalamic and hippocampal brain regions34.

Lastly, our findings may indicate an altered homeostatic sleep drive in AAV8-P301L mice as they age. Since the AAV8-P301L mice sleep more during the onset of the dark/active phase with age, they may be displaying a compensatory need for sleep, especially since sleep deprivation increases tau deposition24,26,35. The normal physiological sleep-wake cycle regulates interstitial fluid (ISF) and CSF levels of tau23, and increasing sleep time may be a mechanism for mitigating tau accumulation. During wake phases, ISF and CSF tau levels are increased23. Since the tauopathy increases circulating tau levels, exacerbated increases in circulating tau may serve as a cue to promote sleep in order to limit or accommodate normal increases in ISF and CSF tau during the wake period. This posited assessment could serve as a means to curtail tau secretion (and limit circulating tau levels) during the wake phase by slowly transitioning into wake. However, the increase in circulating tau levels during the wake phase may represent periods of enhanced tau clearance from the neuron, and reduced time awake could pathologically limit tau clearance and contribute to intraneuronal tau deposition. This would align with reduced levels of insoluble tau (representing tau deposits) during the wake phase in the hippocampus of PS19 mice33. If so, homeostatic tau clearance during the wake phase may be finite, since sleep deprivation (i.e., increased wake time) can increase levels of intraneuronal pathological phosphorylated tau in the brain23,26.

The AAV8-P301L tauopathy model shows sleep deficits in timing and quantity with age. The findings at unique transition periods of the day merits additional circadian studies to further elucidate the neurobiology underlying sleep dysfunction in the AAV8-P301L model. Changes in neurotransmitter/receptor expression, tau secretion, core clock gene expression, and clock-controlled genes should be established in the AAV8-P301L model to further emphasize how circadian biology influences tau pathogenesis. Additionally, this time-of-day specificity in sleep behavior should be further explored in a larger context, such as in Alzheimer’s disease. Beyond neuronal tau deposition, translational indicators of additional neuropathologies may be revealed by emphasizing circadian medicine in neurodegenerative diseases.

Methods

Mice

All animal studies were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use and Committee. The use of recombinant DNA was approved by University of Florida Environmental Health and Safety Office. The C57BL/6 J mice used in this study (N = 4 female AAV8-P301L mice, N = 7 male AAV8-P301L mice, N = 5 female control AAV8 mice, N = 3 male control AAV8 mice) were used in a prior publication, where the tau pathology was thoroughly validated25. No physical anomalies were detected in the mice used for this study. All animals were maintained in 12-h light/dark cycles with ad libitum access to food and water. Mice were anesthetized within an isofluorane induction chamber and euthanized by decapitation for tissue harvest.

AAV injections

Recombinant Adeno-associated virus (AAV) containing P301L tau was produced and injected bilaterally into the ventricles of all neonatal mice (PND 0) with an intracerebroventricular injection as previously described52. AAV8-P301L mice were treated with a construct expressing P301L-tau under the control of the human synapsin promoter was packaged in adeno-associated virus of capsid serotype 8. Control AAV8 mice consisted of mice injected with either an empty AAV8 vector or with an AAV8 capsid carrying a yellow fluorescent protein construct under the control of the human synapsin promoter. All animals were bilaterally injected with 2 μL (1 × 1013 viral genomes) of AAV8 in each hemisphere for a total of 4 μL per mouse, therefore every mouse was treated with viral particles. As these mice were used in a previously published study, the tauopathy-associated neuropathology was previously validated in these mice25.

Sleep measurements

The piezo sleep cage system (Signal Solutions, Lexington, KY) was used in this study to noninvasively measure probability of sleep as previously described. The piezo sleep cage system used in this study allows for the longitudinal monitoring of sleep and wake states and the quantification of minutes spent sleeping per hour of the day over multiple days. Sleep was characterized as previously described36. The high throughput piezo sleep cage system outputs of interest in this study were the total, light, and dark phase sleep durations, sleep bout durations, and sleep bout quantities.

The piezo cage system at the University of Florida is maintained in light-controlled boxes, and therefore hourly sleep probability is presented as related to the zeitgeber time. The AAV8-P301L and AAV8 control mice generated in this study were placed in the piezo cages at 4 months of age and data was recorded for 4 days. The sample sizes were decided based on preliminary experiments performed using 10-month-old AAV8-P301L mice (N = 4) from a previous cohort and N = 3 wildtype C57BL6/J (un-injected) mice, where we found changes in light phase sleep and used this as the basis for our power analysis that indicated N = 3 as a minimum sample size where alpha=0.05 and significant differences can be detected with 80% power. The first day was excluded to account for mouse acclimation behavior. The remarkably consistent sleep data from each mouse is averaged over 3 days. Mice were then placed into the piezo cages again after being aged to 9 months with the same recording and analysis paradigm. As mouse sleep is polycyclic sleep quantity data from the piezo system is presented as percent of the hour spent asleep and sleep bout data from the piezo system is presented as hourly sleep bout mean duration. No mice were placed into sleep cages, and their respective acquired data were excluded from the study.

Biochemical fractionation of mouse brains and western blotting

Cortical tissues were acquired, homogenized, and used for western blotting as previously described25.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9 software was used to perform statistical tests. Results are reported as means ± standard error of the means. A two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests was used to compare AAV8-P301L tau-expressing mice and their respective age and sex-matched controls. A two-way ANOVA with Šidák multiple comparison test was used to measure the 5-month aging effect within each group to independently account for matched values of the same mice at 4 and 9 months. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Responses