Exploring dopa decarboxylase as an ideal biomarker in Parkinson’s disease with focus on regulatory mechanisms, cofactor influences, and metabolic implications

Introduction

PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder after AD. The hallmarks of the disease encompass neuronal loss in the substantia nigra, resulting in striatal dopamine deficiency, and aggregates of alpha-synuclein. Additionally, multiple other cell types of the central and peripheral autonomic nervous systems are participated in PD. Despite the fact that the clinical diagnosis is based on the presence of bradykinesia and other cardinal motor symptoms, PD is accompanied by various non-motor symptoms that add to the overall burden1. PD is also associated by the degeneration of neurons producing other neurotransmitters such as serotonin, melatonin, and norepinephrine2.

It has been 86 years since we first knew about dopa decarboxylase (DDC), or as also commonly known aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD)3. The expression of DDC has been documented in various neuronal and non-neuronal tissues4. Several studies have reported an elevation of DDC in PD. For example, Paslawski et al. reported the elevation of DDC in the CSF of PD patients and suggested its usage as a biomarker for the disease5. Moreover, a recent study found that DDC levels were elevated not only in PD patients at the early stages but also in prodromal patients, using cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and urine samples. Interestingly, DDC could differentiate between PD and AD patients, as it was only elevated in PD6. Another recent study revealed that the levels of DDC in the CSF of PD patients increased as the DaT-SPECT striatal binding ratios (SBR) decreased7. Additionally, some researchers demonstrated that both CSF and plasma levels of DDC can accurately identify patients with Lewy body disease (LBD) and are correlated with poorer cognitive performance. They also discovered that DDC can detect preclinical stages of LBD in clinically unimpaired individuals and predict the progression to clinical LBD over a 3-year period in preclinical cases. Furthermore, DDC levels were found to be elevated in atypical Parkinsonian disorders but not in non-Parkinsonian neurodegenerative disorders8.

All these studies have reported the elevation of DDC in PD patients, both with and without LBD, and demonstrated that DDC can effectively discriminate between PD and other neurodegenerative disorders. Consequently, several researchers are now investigating this enzyme to determine whether it is the ideal biomarker for the early detection of PD. This interest follows a prolonged period during which DDC was considered unremarkable, potentially due to the erroneous and dogmatic viewpoint that this enzyme is non-specific and widely distributed, as well as its classification as a non-rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of dopamine9. In this review, we examine the literature to ascertain whether altered levels of DDC are exclusively correlated with PD and address the question: “Why is this elevation not reflected in increased levels of dopamine?”

Insights into DDC

The human DDC gene is located on chromosome 7 (7p12.1–7p12.3) and exists as a single copy. Several alternative splicing events within the 5’ untranslated regions (5’ UTR) result in the production of different neuronal and non-neuronal mRNA transcripts, all encoding the same protein. It is noteworthy that neuronal mRNA of DDC has been observed in non-neuronal tissues such as the kidney, placenta, leukocytes, and liver cells4. The human DDC protein is a 50 kDa protein that belongs to the aspartate aminotransferase family (fold type 1) of pyridoxal-5-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzymes. Its catalytically active form exists as a homodimer10,11.

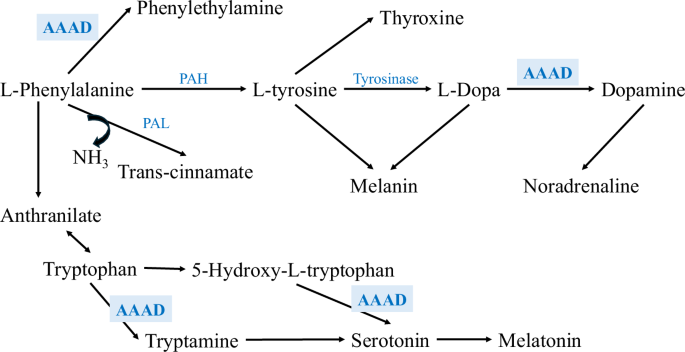

Apart from synthesizing catecholamines, DDC has been shown to be responsible for synthesizing serotonin and trace amines; thus, the name aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD) is more descriptive of this enzyme’s functions12. DDC can metabolize phenylalanine, L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA), tryptophan, and 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) into phenylethylamine, dopamine, tryptamine, and serotonin, respectively (Fig. 1)2,12. Therefore, any alteration in the activity of DDC will affect not only the production of dopamine but also the production of DDC’s other products.

A schematic representation of the dopamine synthesis pathway, starting with phenylalanine. Phenylalanine is converted to tyrosine by phenylalanine hydroxylase, followed by the production of L-DOPA via tyrosinase. Then, DDC catalyzes the decarboxylation of L-DOPA to produce dopamine2.

DDC is an ideal biomarker candidate for PD

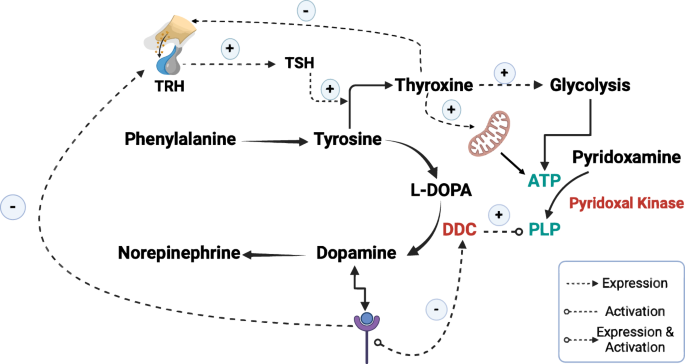

The regulation of DDC suggests its potential as an ideal biomarker for PD, given the disease’s hallmark dopamine deficiency from dopaminergic neuron loss13. Literature reveals two primary regulatory mechanisms for DDC. First, dopamine receptor antagonists enhance DDC-coding mRNA expression pre-translationally (Fig. 2)9,14. Cumulative evidence supported this notion; for instance, chronic D1 and D2 receptor blockade increases DDC mRNA in brain and midbrain nigrostriatal neurons and its striatal activity15,16. Moreover, another study found that a single dose of clozapine escalates DDC activity dose- and time-dependently in the mouse striatum, with concurrent increases in DDC protein and mRNA across various brain regions17. These findings collectively indicate that reduced dopamine levels, linked to decreased dopamine-receptor binding, upregulate DDC expression.

It also demonstrates how thyroxine enhances the production of ATP by increasing the expression of enzymes involved in glycolysis and by enhancing the mitochondrial activity. This ATP is a crucial cofactor for pyridoxal kinase to convert pyridoxamine to PLP, which is essential for activating DDC. Furthermore, this figure highlights how the binding of dopamine to its receptor inhibits both the expression and phosphorylation of DDC and the expression of TRH in the hypothalamus. TRH induces the production of TSH in the pituitary gland, which stimulates the production of thyroxine. Noting that (+) means induction and (−) means inhibition. This figure was generated using Biorender.

The second regulatory pathway involves post-translational modulation, where dopamine binding to its receptor suppresses DDC activity by inhibiting its phosphorylation—a crucial step for enzyme activation (Fig. 2)9,14. This concept finds further support in studies demonstrating that dopamine receptor binding reduces DDC activity18. Moreover, researchers have observed that acute administration of selective or mixed D1, D2, D3, or D4 antagonists enhances striatal DDC activity, a response also seen with multi-receptor drugs targeting D2-like receptors such as clozapine9.

PET studies have reported intriguing findings: administration of haloperidol in humans has been associated with elevated DDC activity19,20, whereas another study demonstrated reduced DDC activity in the macaque striatum following MAO B inhibition21. In another notable PET study investigating F-L-DOPA uptake, researchers found that drug-free schizophrenic patients exhibited decreased DDC activity in the ventral striatum, which was subsequently increased upon administration of typical and atypical antipsychotics22. These findings collectively suggest that dopamine receptor binding diminishes both the expression and activity of DDC, and conversely, alterations in DDC activity can influence dopamine receptor signaling.

While much of the literature focuses on the regulation of DDC by dopamine receptors, there is evidence indicating that the enzyme can also be regulated by the glutamatergic and serotonergic systems. However, both of these systems regulates DDC at significantly lower rates compared to the dopaminergic system, particularly in nigrostriatal neurons, where DDC activity is predominantly under dopaminergic control. Studies have demonstrated that dopamine receptors regulate DDC activity through both presynaptic (D2, D3) and postsynaptic (D1, D2) mechanisms9.

In summary, decreased dopamine levels resulting from dopaminergic degeneration in PD, which manifest as reduced dopamine-receptor binding, lead to increased expression and activity of DDC. This characteristic positions DDC as an ideal biomarker for diseases characterized by dopaminergic degeneration.

Conversely, it is crucial to consider an important question: if the body’s compensatory mechanism for overcoming dopamine deficiency involves enhancing the expression and activation of DDC to convert more L-DOPA into dopamine, why do patients with PD exhibit lower serum and plasma levels of not only dopamine but also serotonin, melatonin, and norepinephrine, despite these neuro-molecules being producible by the body’s non-neuronal cells? For instance, enterochromaffin cells (ECCs), non-neuronal cells and subtype of enteroendocrine cells (EECs), are responsible for the production of 95% of the body’s total serotonin23. Moreover, the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla produce catecholamines, including norepinephrine and dopamine24.

PLP deficiency in PD

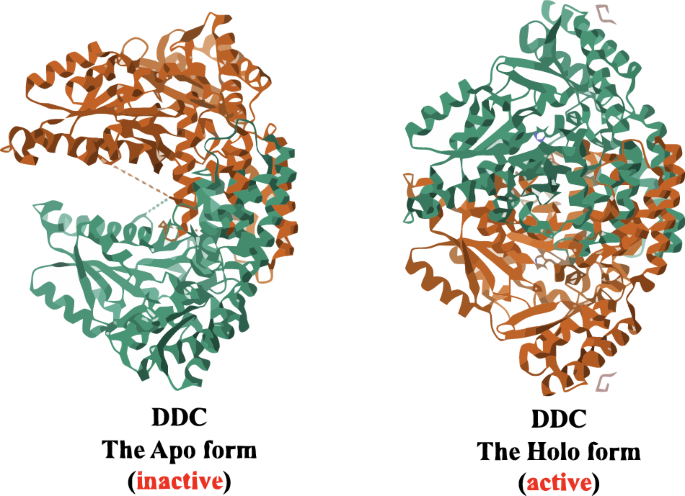

As previously discussed, DDC is a PLP-dependent enzyme, and therefore, binding to PLP is essential for its complete activation10,11. PLP-dependent enzymes undergo biosynthesis initially as inactive apo-B6 enzymes, which become active holo-B6 enzymes upon covalent binding with PLP (Fig. 3)25,26.

It shows the 3D protein structure of DDC in its two forms: the inactive apo form and the active holo form26.

Our recent metabolomic study, in conjunction with studies by colleagues, has revealed lower levels of PLP in PD patients2. For instance, one study reported lower serum B6 levels in PD patients compared to controls, noting an association with decreased hepatic enzymes AST and ALT27. Additionally, a case study documented severe vitamin B6 deficiency in a male PD patient with refractory seizures, which were alleviated by high-dose steroid therapy and intravenous vitamin B6 treatment, with continued vitamin B6 supplementation post-discharge28. Another case study involving a PD woman admitted to the hospital with a generalized epileptic seizure found a significant decrease in the active form of vitamin B6, PLP29. Furthermore, metabolic markers indicative of PLP deficiency were identified in the brains of PD patients in a separate study30. Nonetheless, another study established a correlation between low plasma PLP levels and PD31.

In our previous metabolomics study, we observed that levels of pyridoxamine, the inactive form of vitamin B6, were significantly higher in PD patients compared to reference controls. This finding suggests a potential alteration in the function of pyridoxal kinase, the enzyme responsible for activating this vitamin. Interestingly, we found no significant difference in pyridoxamine levels between PD patients and high-risk controls, nor between reference controls and high-risk controls, indicating that this kinase alteration may be associated with the initiation of the disease2.

It is important to note that pyridoxal kinase relies on adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to phosphorylate its substrate, pyridoxamine, thereby producing PLP (Fig. 2)32. Several studies have reported lower levels of ATP and NAD+ in PD. For instance, researchers have observed impaired mitochondrial function and reduced ATP production in skin biopsies from PD patients with LRRK2G2019S 33. Another study found that the levels of both ATP and NAD+ were lower in the muscles of PD patients than in those of controls34. Furthermore, numerous studies have documented mitochondrial dysfunction and significant impairment of ATP synthesis pathways in PD35.

Given the complexity of PD, our investigation delved into upstream ATP production pathways from various perspectives. Numerous researchers have highlighted lower rates of glycolysis in PD patients compared to controls36. For example, PET and single photon emission computed tomography studies have demonstrated significantly reduced cortical glucose consumption in early-stage PD37,38. Another study identified significant reductions in the levels of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, key enzymes in glycolysis, in the putamen of early-stage PD patients39. These findings are consistent with our previous study, where we observed markedly lower levels of glucose-6-phosphate in PD patients compared to controls2.

At this juncture, we considered whether a deficiency in PLP in PD patients might be the underlying cause of the observed improper functioning of DDC. This prompted us to revisit the earlier question: “If dopaminergic neurodegeneration is responsible for the reduced dopamine levels, thereby increasing the expression and activation, via phosphorylation, of DDC; thus, why are peripheral levels of other neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine and serotonin, also reduced?” We began to question whether the diminished PLP levels or lower levels of DDC substrates, such as L-DOPA that is produced by the hydroxylation of tyrosine, are impeding the proper activity of DDC.

The effect of tyrosine deficiency and altered thyroid function on PLP production in PD

To address the aforementioned question, we, firstly, need to understand the multifaceted roles of tyrosine in PD, the role of thyroxine in ATP production, and the dopamine-thyroxine complex relationship. Tyrosine, a non-essential amino acid, serves as a precursor to both L-DOPA (dopamine precursor) and the thyroid hormone, thyroxine40. Thyroxine is known to regulate glucose metabolism and enhance the activity of hexokinase, the enzyme responsible for initiating glycolysis by converting glucose to glucose-6-phosphate, yielding ATP, NADH, and pyruvate—a process crucial for activating pyridoxal kinase and converting pyridoxamine to PLP (Fig. 2)32,41,42. Moreover, research revealed that T3 has genomic and non-genomic regulatory mechanisms on mitochondria. For example, T3 can stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis, modify the composition of the inner membrane, and enhance the uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. 2)43,44. Researchers also found that T3 can bind to specific sites in the inner membrane and increase the consumption of oxygen. Additionally, the discovery of 43 kDa c-Erb Aα1 protein (p43) functioning as T3-dependent mitochondrial transcription factor has highlighted the hormone’s influence on the mitochondrial gene expression45. Although thyroxine has been identified as the main regulator of mitochondrial health and ATP production, studies showed that both higher and lower levels of thyroxine can lead to mitochondrial toxicity and lower availability of ATP46,47.

Dopamine-thyroxine complex interaction

The relationship between dopamine and thyroxine is highly intricate. Despite both being synthesized from the same precursor, tyrosine, dopamine exerts a regulatory effect on thyroxine expression. Dopamine strongly inhibits the expression of thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) and prolactin in humans48. Consequently, several studies have reported that the binding of dopamine to its receptor inhibits the production of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and significantly reduces thyroxine levels (Fig. 2)49,50. Additionally, other studies have indicated that dopamine antagonists induce the expression of TRH51,52. However, it is crucial to recognize that the biosynthesis of thyroxine depends on the availability of both tyrosine and iodide53. It is also important to note that tyrosine, as the substrate for the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine biosynthesis, may be consumed more rapidly by the thyroid gland than by the dopaminergic system; this area requires further investigation to substantiate this claim. Additionally, it is essential to understand that the primary regulator of TRH and TSH is thyroxine itself, via the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis, wherein high thyroxine levels inhibit the expression and release of TRH and, consequently, TSH (Fig. 2)54. Table 1 presents various cases of thyroid alterations with corresponding levels of TSH and T451,52,55.

Hyperthyroidism in PD

After searching the PubMed database, we found only three studies reporting the levels of TSH, TRH, and thyroxine in PD patients with hyperthyroidism. The first study documented two PD patients with hyperthyroidism who exhibited dyskinesia and the on-off phenomenon, both of which resolved after the administration of anti-thyroid treatment. Laboratory tests showed elevated levels of total thyroxine; however, after the TRH stimulation test, the TSH levels, which were already reduced in these patients, did not show any elevation56. This study demonstrates that the elevated levels of thyroxine effectively inhibited the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, highlighting that the excessive production of thyroxine is not due to hyperactivation of the hypothalamus by reduced levels of dopamine.

Additionally, a case report described a female PD patient whose tremors were refractory not only to anti-parkinsonian treatment but also to deep brain stimulation. This patient was diagnosed with thyrotoxicosis (TSH < 0.01 mlU/L, normal range: 0.4–4.0 mlU/L; fT3 = 13.3 pmol/L, normal range: 3.0–6.5 pmol/L; fT4 = 48.3 pmol/L, normal range: 9.0–23.0 pmol/L). After 2 weeks of anti-thyroid treatment, her tremors improved57; Given that the TSH levels were low, this study indicates that the elevation in thyroxine was not due to reduced dopamine levels, suggesting another type of hyperthyroidism that can be detected by performing additional laboratory tests, such as assessing the levels of thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins (TSIs) or thyroid-stimulating antibodies (TSAb).

On the other hand, a retrospective study examined the levels of TSH and T4 in PD patients compared to controls and found that subclinical hyperthyroidism was more common in PD patients than in matched controls58. This study further supports the notion that the hyperthyroidism cases reported in PD patients are not due to reduced dopamine levels, but rather other causes that may be coincidental or require further investigation to uncover.

Therefore, we recommend that PD patients undergo more than just basic thyroid function tests to diagnose hyperthyroidism and understand the underlying pathological mechanisms, as these may involve immunological causes. In this context, we suggest that PD patients with hyperthyroidism experiencing worsening symptoms may do so due to two possible causes: (1) hyperthyroidism is associated with severe mitochondrial dysfunction leading to proton leak and lower ATP production, which affects the production of PLP and, consequently, the activity of DDC32,47, and (2) patients with hyperthyroidism consume higher amounts of tyrosine, which is the substrate for both thyroxine and L-DOPA, depriving the remaining dopaminergic neurons of the ability to produce sufficient amounts of dopamine.

Hypothyroidism in PD

On the other hand, other studies have reported lower levels of thyroxine in PD patients compared to controls. For instance, recent research has shown significantly higher levels of TSH and markedly reduced levels of T3 and T4 in euthyroid PD patients compared to non-PD controls, with these reductions inversely correlated with disease subtype and severity59. Furthermore, case studies have indicated that PD patients may exhibit symptoms of hypothyroidism, which can be masked by PD symptoms. For example, a female patient with a 17-year history of PD and undergoing L-DOPA/carbidopa treatment was admitted to the hospital in a continuous off state, exhibiting lethargy, muscle cramps, and constipation. Laboratory tests revealed hypothyroidism, and treatment with levothyroxine sodium alleviated her symptoms, reducing the off state by 40%60. Another case study highlighted delayed diagnosis of hypothyroidism in a PD patient due to overlapping symptoms61. It is important to mention that hypothyroidism is not only associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and a significant reduction in ATP levels but also with a 24% decrease in cerebral blood flow and a 12% reduction in cerebral glucose metabolism in humans62. These studies showed higher levels of TSH, which may be due to either dopamine deficiency or typical hypothyroidism. Also, they exhibited lower levels of thyroxine, arising a question: are these reduced thyroxine levels, despite the induced levels of TRH and TSH, represent a concurrent disease of hypothyroidism, or are they a reflection of lower tyrosine levels in PD?

Tyrosine deficiency in PD

In a matter of fact, several studies have reported alterations in the levels of tyrosine in PD. As early as 1969, Braham et al. hypothesized that impaired hydroxylation of tyrosine might be associated with PD. They conducted oral loading tests with L-phenylalanine and tyrosine on PD patients and controls, finding lower phenylalanine levels in PD patients compared to controls, though tyrosine levels did not significantly differ, suggesting a potential alteration in phenylalanine metabolism63. Conversely, a recent study identified reduced tyrosine levels in PD patients and proposed an alteration in phenylalanine metabolism30. Another study supported this finding by reporting a lower tyrosine to phenylalanine ratio in both de novo and L-DOPA-treated PD patients compared to controls, further highlighting potential metabolic changes in phenylalanine metabolism64.

Interestingly, our recent metabolomic profiling also revealed decreased levels of tyrosine and phenylalanine, and higher levels of trans-cinnamate, a phenylalanine metabolite, in both PD patients and high-risk controls compared to reference controls. This finding suggests a metabolic shift where phenylalanine is directed towards producing higher amounts of trans-cinnamate via phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) rather than the normal production of tyrosine through phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH)2. Supporting this metabolic shift, recent studies have shown lower PAH activity in PD patients65,66. These findings underscore an important point: if tyrosine levels are reduced in PD due to altered phenylalanine metabolism, the resulting deficiency in L-DOPA can hinder dopamine production, potentially increasing DDC production and phosphorylation.

Supporting this notion, normally, the remaining functional dopaminergic neurons in PD patients rely on exogenous L-DOPA, utilizing their DDC to convert L-DOPA into dopamine, thereby alleviating symptoms67. Thus, the effectiveness of exogenous L-DOPA as the primary treatment for PD strongly suggests an endogenous L-DOPA deficiency, which may reflect lower tyrosine levels. A recent study found that L-DOPA levels were reduced in the plasma of individuals at risk of developing PD at the prodromal stage68, aligning with our previous findings reporting lower L-DOPA in both PD patients and high-risk controls2. Another study reported that the levels of L-DOPA in the CSF of high-PD-risk participants were significantly decreased; interestingly, after 3.7 years, 4 of the 26 high-PD-risk participants developed PD69.

In summary, lower levels of tyrosine may have detrimental impacts in PD. Insufficient levels of tyrosine potentially lead to reduction in both thyroxine and L-DOPA levels. Decreased availability of L-DOPA, which is the substrate for DDC, can lead to diminished dopamine production. Moreover, reduced tyrosine levels may also affect thyroxine and ATP synthesis, thereby influencing the biosynthesis of PLP, crucial for activating the extensively expressed DDC and compensating for dopamine deficiency. Importantly, this systemic decline in dopamine levels and reduced DDC activity due to PLP deficiency can also impact the levels of norepinephrine, serotonin, and melatonin in both neuronal and non-neuronal cells.

Fluorodopa PET imaging and DDC in PD

Fluorodopa (F-DOPA) PET imaging has become a pivotal tool in understanding the pathophysiology of PD, particularly in tracking changes in dopaminergic activity. DDC is required to metabolize F-DOPA into fluoro-dopamine (18F-dopamine). The hallmark finding in PD is the decreased striatal uptake of F-DOPA, reflecting the progressive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta70. Moreover, an animal study using MPTP-induced parkinsonian monkeys provided further confirmation of these findings, showing increased uptake of F-DOPA in certain brain regions. The researchers attributed this heightened uptake to elevated levels of DDC. These observations complement evidence from human studies that highlight variations in F-DOPA uptake patterns in PD71.

On the other hand, interesting observations in early PD suggest an increased F-DOPA uptake in several extra-striatal brain regions; for instance, Ghaemi et al. showed a significant increase in F-DOPA uptake in the pineal gland of the early-stage PD patients, a region typically not associated with dopaminergic signaling under normal conditions72. Similarly, other colleagues reported elevated F-DOPA uptake in the raphe nuclei in PD patients compared to controls73. In addition, another study demonstrated increased F-DOPA uptake in the prefrontal cortex74. These findings collectively suggest that the increased F-DOPA uptake in extra-striatal areas may represent a compensatory mechanism aimed at countering the dopaminergic deficit in the striatum.

Interestingly, the raphe nuclei, known for their role in serotonin production, and the pineal gland, responsible for melatonin synthesis, also rely on DDC for the decarboxylation of their respective precursors, 5-HTP and 5-methoxytryptophan75,76. This raises the question: if these regions exhibit elevated functional DDC to compensate for reduced dopamine, why does this not correspond to an increase in serotonin and melatonin synthesis? Studies suggest that PD is associated with reduced serotonin and melatonin production in these regions. For instance, serotonergic dysfunction in the raphe nuclei has been consistently documented in PD, with evidence of decreased serotonin levels and serotonergic neuron degeneration77. Similarly, melatonin production by the pineal gland is impaired in PD, with lower nocturnal melatonin levels observed in affected individuals78. These findings imply that while DDC activity may be upregulated to support dopamine synthesis, other factors likely limit serotonin and melatonin production in PD.

An additional perspective involves the interplay between PD-associated tyrosine deficiency and F-DOPA metabolism. As mentioned earlier, tyrosine, as the precursor of the endogenous L-DOPA, is reportedly lower in PD patients compared to controls. This deficiency may limit endogenous L-DOPA synthesis in PD, creating a scenario where administered FDOPA is preferentially taken up and utilized. In contrast, non-PD individuals with adequate tyrosine levels and sufficient endogenous L-DOPA synthesis might rely less on exogenous F-DOPA for dopaminergic activity. Thus, the observed increase in extra-striatal F-DOPA uptake in PD could be partially explained by the heightened demand for dopamine precursors in the face of limited tyrosine availability.

This hypothesis raises critical questions about the metabolic alterations in PD and their impact on F-DOPA PET findings. Does the reduced tyrosine availability in PD not only shift F-DOPA utilization dynamics but also highlight potential therapeutic targets? Future research should focus on unraveling these mechanisms and exploring whether tyrosine supplementation might influence F-DOPA distribution or improve dopaminergic function in PD.

DDC levels in the plasma of PD patients

Although some notable studies found that DDC was elevated in the plasma of both drug-naïve and L-DOPA/carbidopa treated PD patients8, some studies have indicated that the increase in DDC levels observed in the plasma of PD patients is primarily significant in those receiving treatment and not in de novo and prodromal patients, suggesting that the therapy itself may drive the upregulation of this enzyme in the plasma79. This discrepancy highlights the need to investigate the underlying mechanisms contributing to DDC elevation in PD patients. It is possible that dopaminergic therapies, such as L-DOPA and carbidopa, may directly or indirectly influence DDC expression or its release into the plasma. For example, carbidopa, a peripheral DDC inhibitor, might induce compensatory changes in enzyme expression due to feedback mechanisms aimed at maintaining dopamine synthesis. Conversely, the lack of significant DDC elevation in de novo and prodromal patients could reflect the absence of such treatment-induced regulatory effects, further supporting the role of therapy in modulating peripheral DDC levels.

Additionally, other factors, such as alterations in peripheral metabolism, cofactor availability (e.g., PLP), or the availability of L-DOPA precursors could play a role in the observed variability of DDC levels. For example, tyrosine, which is abundant in protein-rich diets, could be preferentially utilized peripherally rather than centrally in PD due to changes in blood-brain barrier (BBB) dynamics80,81,82. This may increase the peripheral availability of L-DOPA precursors, thereby influencing DDC activity and expression in the plasma of PD patients. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for clarifying the peripheral versus central roles of DDC in PD pathology and for optimizing therapeutic strategies that address the differential utilization of precursors and cofactors across compartments.

Conclusion

This perspective emphasizes that DDC is responsible for synthesizing not only dopamine and norepinephrine but also tryptamine, serotonin, and, consequently, melatonin. Furthermore, we demonstrated that elevated levels of DDC can serve as an ideal biomarker for the detection of PD, as reported by several studies. Some of these studies successfully discriminated PD patients from those with other neurodegenerative disorders. We propose that DDC is an ideal biomarker for PD, as it has been proven to be dominantly regulated by dopamine levels. PD is characterized by reduced dopamine levels, which have been shown to increase the expression and phosphorylation of DDC. However, the review addresses a significant question: if DDC is highly expressed and readily activated by phosphorylation, and it is widely distributed in the body, why are the levels of certain neuro-molecules, such as serotonin and norepinephrine, reported to be low, especially considering that these molecules can be produced by non-neuronal cells peripherally?

Therefore, we conducted a comprehensive literature review from various perspectives to address the aforementioned question. Our findings indicate that several studies have reported lower levels of PLP, a crucial cofactor necessary for proper DDC activation, in PD patients. Additionally, we identified that PD patients exhibit lower levels of ATP and NAD+, crucial for generating PLP, along with reduced mitochondrial activity. These findings suggest that despite elevated DDC levels, its functionality is impaired. This may explain why these elevated DDC levels do not compensate the dopamine deficiency or correspond to higher levels of serotonin, norepinephrine, and melatonin.

In our exploration of DDC, we encountered several studies indicating potential alterations in phenylalanine metabolism that could lead to lower tyrosine levels, the precursor for both thyroxine and L-DOPA. This resulted lower levels of L-DOPA could potentially explain the initial lower levels of dopamine in the disease. Additionally, thyroxine is known to regulate glycolysis and ATP production. Researchers have also noted lower thyroid functions in PD patients, which is possibly due to the reduction of tyrosine levels in the patients. Conversely, few studies reported hyperthyroidism in PD. After reviewing the available literature on thyroid function in PD patients with hyperthyroidism, it is evident that the interaction between thyroid hormones and dopaminergic pathways is complex and multifaceted. The studies we examined provide compelling evidence that elevated thyroxine levels in PD patients with hyperthyroidism do not result from reduced dopamine levels or hyperactivation of the hypothalamus. Instead, they underscore the importance of comprehensive thyroid assessments beyond basic function tests to elucidate underlying mechanisms. However, it is important to note that both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and reduced ATP production. This reduction in ATP consequently diminishes the production of PLP, thereby impairing the functionality of DDC. Collectively, all these findings may suggest that PD is a complex metabolic disorder.

In conclusion, DDC shows significant promise for PD due to its elevated presence and its potential to distinguish PD from other neurodegenerative diseases. However, further studies are necessary to address current gaps and validate DDC’s clinical utility. Advancing this research could improve early diagnosis and treatment strategies for PD, thereby enhancing patient outcomes.

Responses