Mechanism of amyloid fibril formation triggered by breakdown of supersaturation

Introduction

Amyloid fibrils are fibrillar and ordered aggregates of denatured proteins, associated with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases and dialysis-related amyloidosis1,2. Today, more than 40 human amyloidogenic proteins are known2. These diseases are caused by the deposition of amyloid fibrils or oligomers at various sites in the brain and body. Amyloid fibrils are formed after a lag time during which amyloid nuclei or oligomers are formed in the initial process. Oligomers may be another type of protein aggregates formed above the solubility limit and have been proposed to be directly involved in cytotoxicity3. In general, however, it takes several years to decades to form amyloid deposits in vivo, and various in vitro methods have been developed to amplify amyloid fibrils seed-dependently or accelerate amyloid nucleation. These include protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA)4,5, real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC)6,7, immunoprecipitation (IP) followed by RT-QuIC (IP/RT-QuIC)8, microfluidic quaking-induced conversion (Micro-QuIC), an acoustofluidic platform for rapid detection of protein misfolding diseases9, and HANdai Amyloid Burst Inducer (HANABI)10,11. Mechanical stresses such as agitation12,13, fluid flow14,15, ultrasonication10,16, when applied to precursor proteins, markedly accelerate amyloid formation by breaking supersaturation (Fig. 1a) through increased collisions, collapse of the native structure and other factors. On the other hand, various kinds of additives have been shown to accelerate spontaneous amyloid formation through the solvation or macromolecular crowding effects, as described below. Common to this mechanical and additive-dependent amyloid formation, solubility and supersaturation play crucial roles. This review addresses the mechanism of amyloid formation and the development of equipment for detecting amyloid seeds and nucleation from the viewpoint of solubility- and supersaturation-limited amyloid formation.

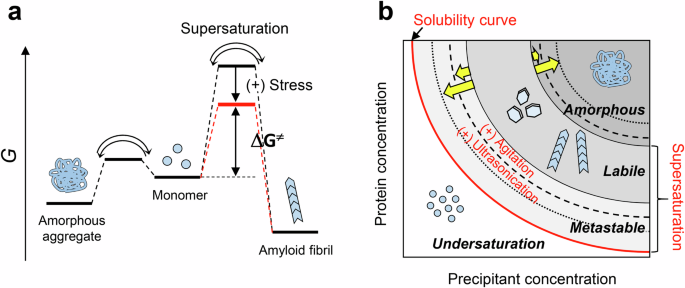

a Free energy diagram with (red) and without (black) physical stress. The aggregation reaction starts from a monomeric state to amyloid fibrils or amorphous aggregates. ΔG≠ is transition free energy. b Concentration-dependent solute and precipitation phase diagram common to native crystals and aggregates of denatured proteins. The phase boundaries between amorphous and labile regions or between labile and metastable regions under quiescence are altered by agitation and ultrasonication70.

General mechanism of amyloid formation

Amyloid fibrils are one-dimensional crystal-like fibrillar aggregates, which are distinct from monocrystals with three-dimensional orders. However, the mechanism of amyloid formation is essentially the same as that of crystallization of a solute, being determined by solubility and supersaturation. The relationship between solubility and supersaturation can be illustrated by the crystallization of sodium acetate in metastable regions of supersaturation, where the sodium acetate concentration is slightly higher than the critical concentration (i.e., solubility) and supersaturation persists due to a high energy barrier for nucleation17,18. However, agitating the solution with a piece of metal readily causes a sudden and marked phase transition from soluble to solid states linked with the breakdown of supersaturation. This phase transition is accompanied by heat emission, the enthalpy change of crystallization. After the phase transition, the soluble sodium acetate concentration decreases toward solubility18. In vivo, various types of lithiasis, such as urolithiasis, cholelithiasis, and nephrolithiasis, are caused by the crystallization of small compounds: oxalate, cholesterol gallstones, and calculus, respectively19. The basic mechanism of lithiasis is the same as that of sodium acetate crystallization and is determined by solubility and supersaturation. With a similar mechanism, supersaturated amyloidogenic proteins nucleate and form amyloid fibrils, where in vivo mechanical stresses have been suggested to be important to break supersaturation by molecular collisions or protein denaturation due to mechanical stresses, may result in the formation of small amounts of nuclei, which in turn lower the free energy barrier (Fig. 1a).

Amyloid formation can be illustrated by a conformational phase diagram of an “unfolded” protein dependent on precipitant and protein concentrations (Fig. 1b)18. The supersaturation ratio (σ) or degree of supersaturation (S) is an important parameter to quantify the phase diagram20:

where [C] and [C]C are the initial solute concentration and thermodynamic solubility, respectively. σ and S are 1 and 0, respectively, at the solubility limit (Fig. 1b), and these values increase from the metastable to labile state with an increase in the driving force of precipitation (i.e., increases in precipitant or protein concentrations). In the amorphous region, amorphous aggregation without a lag time makes it difficult to evaluate the σ or S value.

Below saturation (0 < σ < 1) at a low protein or precipitant concentration, the protein remains as a monomer in solution (i.e., below solubility). At a critical concentration (σ = 1), the protein concentration is equal to solubility. In a metastable state where the protein concentration is slightly higher than solubility (1 ≤ σ), amyloid fibrils cannot form without seeding because of the stability of protein supersaturation, and in a labile state where the protein concentration is much higher than solubility, amyloid fibrils spontaneously form after a certain lag time (1 ≪ σ). As their concentration increases further, the protein readily forms amorphous aggregates. The metastable and labile states are called supersaturated states. The mechanical stresses decrease the free energy barrier of supersaturation, which facilitates amyloid formation (Fig. 1a). In a phase diagram, mechanical stresses shift the phase boundary between metastable and labile states, inducing amyloid formation even in a metastable state.

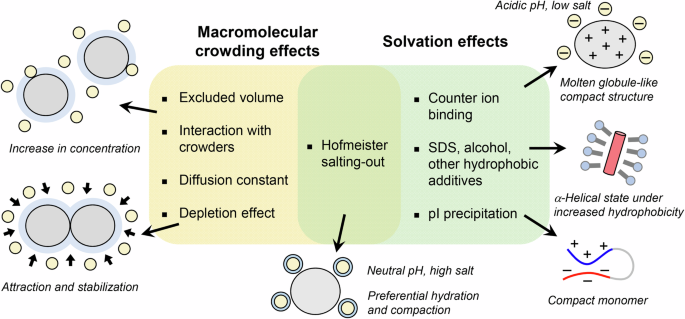

On the other hand, the solvent conditions accelerating amyloid formation can be classified into two types based on the underlying effects: One is the macromolecular crowding effect, which increases σ by decreasing the water-accessible volume and increasing the apparent solute (i.e., protein) concentration. The other is the solvation effect, which increases the degree of supersaturation by decreasing the solubility (Fig. 2).

Macromolecular crowding and solvation effects modulate the solute concentration and solubility, respectively, through distinct mechanisms, which lead to amyloid formation after breaking supersaturation. The same mechanism may work adversely on folded proteins, stabilizing the native state and possibly native-state crystallization.

The rigidity of supersaturation is represented by the nucleation time (tnuc), which is related to the supersaturation ratio (σ) based on the following equation (3):

where α is a dimensionless empirical constant, and β is composed of several variables depending on the properties of the solutes and absolute temperature. The relationship given by Eq. (3) has been demonstrated experimentally in small compounds and proteins21,22.

To date, the physiochemical mechanisms underlying supersaturation have been extensively studied. The classical mechanisms proposed by Oosawa and Kasai23 are based on actin polymerization and consider that the entropic barrier for associating molecules to form a nucleus underlies supersaturation. The classical nucleation theory also considers a similar supersaturation barrier24. Subsequent studies have suggested a more complex mechanism of supersaturation, in which solute is kinetically trapped, occurring in distinct pathways to form crystals, consistent with Ostwald’s ripening rule of crystallization17.

Recently, the atomic structures of various amyloid fibrils have been shown to be ordered β-sheet structure stabilized by hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions, and van der Waals interactions25,26,27. Nevertheless, these structures do not clarify the physicochemical mechanisms that underlie the development, retention, and breakdown of supersaturation, or the role of supersaturation in amyloid nucleation. Further physicochemical studies to advance knowledge of supersaturation will be essential for an understanding of the mechanism of amyloid formation18,28.

Classification of amyloid-accelerating conditions

Although the breakdown of supersaturation is a required process for the amyloid nucleation and crystallization of solutes, amyloid fibrils are formed under varying solvent conditions by distinct mechanisms, which can be classified into effects of solvation and macromolecular crowding (Fig. 2)18.

Solvation effects on amyloid formation

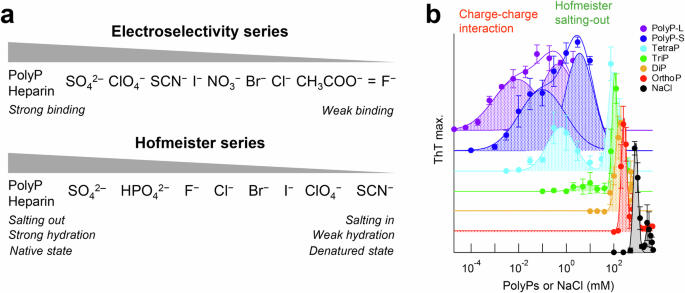

The effects of salts12,29,30,31, alcohols32,33, detergents34, lipids35,36, and other biopolymers37,38 on protein aggregation or stabilization have been investigated. These solvation effects include: (i) a counter ion-binding mechanism observed mainly in moderate concentrations of salt under acidic conditions, as shown in an electroselectivity series (Fig. 3a, top); (ii) a salting-out mechanism observed independent of pH under high-salt conditions, shown in the Hofmeister series (Fig. 3a, bottom); (iii) a hydrophobic additive-binding mechanism observed in moderate concentrations of detergents like SDS or membrane surface, alcohols (Fig. 2); and (iv) pI-precipitation under low-salt conditions, where proteins form compact conformation by hydrophobic interaction39. These effects differ in the concentration range and the order of effectiveness of the additives.

a Electroselectivity series (top) and Hofmeister series (bottom). b Effects of polyP on amyloid formation of αSyn. Amyloid formation in the presence of various chain lengths and concentrations of polyPs plotted against polyPs or NaCl concentration. Thus, polyP accelerated amyloid formation of αSyn through the charge-charge interaction and Hofmeister salting-out in a concentration-dependent mechanism. Reproduced with permission from ref. 41.

In the Hofmeister series, kosmotropic ions (e.g., sulfate and phosphate anions), which make water structure, have a strong effect on the salting-out and protein stabilization than chaotropic ions (e.g., thiocyanate and perchlorate anions), which break water structure at higher concentrations of salts (Fig. 3a, bottom). Comparing the order of the monovalent halide anions between the electroselectivity series (I− > Br− > Cl− > F−) and Hofmeister series (F− > Cl− > Br− > I−), their effectiveness on protein aggregation is opposite. It is notable that the effectiveness of divalent SO42‒ and phosphate is greater than monovalent anions for both series. This can be explained as follows: Kosmotropic anions with a smaller radius (e.g., F−) hydrate more water molecules than chaotropic anions with a larger radius (e.g., I−), which increases the apparent radius and weakens the direct electrostatic interaction with proteins. However, the salting-out effect of kosmotropic anions in the Hofmeister series is stronger because they absorb more water molecules than chaotropic anions, decreasing the concentration of free water molecules, and thus increasing net protein concentrations.

Raman et al.29 examined the effect of salts on amyloid formation of β2-microglobulin (β2m) at pH 2.5, where β2m was denatured. The effects of various anions were shown that amyloid formation was accelerated through the counter anion-binding mechanism of the electroselectivity series at relatively lower concentrations of salts. Munishkina et al.12 examined amyloid formation of α-synuclein (αSyn) using varying kinds of salts at a neutral pH. These effects were followed by anion-binding mechanism at lower concentrations of salts and salting-out effect in the Hofmeister series at higher concentrations of salts, although the role of cations might alter under some conditions.

αSyn is an intrinsically disordered protein consisting of 140 amino acid residues and is a causative protein of synucleinopathies including Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy, and dementia with Lewy bodies. To understand the mechanism of amyloid formation of αSyn, the effects of various additives were further studied including salts and polyphosphate (polyP)40,41. PolyP is an anionic biopolymer composed of inorganic phosphates linked by high-energy phosphate bonds and is found in various microorganisms and human cells42. Interestingly, there are two optima of polyP-dependent amyloid formation (Fig. 3b). The optimum at lower polyP concentrations could be caused by counter anion-binding between the negatively charged polyPs and positive charges of αSyn, while the optimum at higher polyP concentrations could be caused by preferential hydration of the phosphate groups in the Hofmeister salting-out effects41. Thus, polyP-induced amyloid formation of αSyn involves a concentration-dependent mechanism.

Such bimodal concentration-dependent effects were also observed in the amyloid formation using amylin43, β2m44, and lysozyme45,46. These interactions between proteins and salts, when working intramolecularly, induce conformational change into a more compact structure or stabilization of the native state. Thus, protein folding without supersaturation and amyloid formation is limited by the breakdown of supersaturation compete, leading to amyloid formation only after breaking supersaturation.

Macromolecular crowding effects on amyloid formation

Macromolecular crowding under cellular conditions is also an important factor for understanding amyloid formation in the context of proteostasis (Fig. 2). The effects of molecular crowders on amyloid formation are explained by the following mechanisms47,48,49: (i) excluded volume effects, increasing the effective concentration of amyloidogenic proteins, thus accelerating amyloid formation50; (ii) interaction with crowders (e.g., serum albumin), decelerating amyloid formation49,51; and (iii) a decrease in the diffusion constant, decelerating amyloid formation52. The salting-out effects caused by Hofmeister salts have effects of (i) because the available solvent volume decreases due to water-hydrated ion molecules53.

Another important topic related to macromolecular crowding is liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) and the resultant biomolecular condensates or droplets observed increasingly in disordered proteins. There are cases whereby amyloid formation is preceded by LLPS54,55. For example, the low-complexity domain of the FUS protein formed phase-separated droplets before the amyloid formation56. Importantly, the biomolecular condensates markedly accelerate amyloid formation when proteins are localized at the droplet interface57,58. In addition, amyloid formation was accelerated in the presence of two macromolecular crowders, polyethylene glycol (PEG) and dextran (DEX)59. Under these conditions, the depletion effects working in a micro phase-segregated state with DEX and PEG systems cause condensation of proteins (e.g., αSyn and Aβ1-40) at the interface between the solute PEG and DEX droplets, resulting in accelerated amyloid formation for disordered proteins (Fig. 2). When volume is eliminated by macromolecules, the entropy of system increases as macromolecules approach each other, increasing the space of the small molecules. This thermodynamic effect causes an attractive force between macromolecules by the depletion effects, which arise from excluded volume effect. In contrast, condensation of folded proteins (e.g., HEWL and β2m) at the interface stabilizes the native state. Considering these depletion interactions will further advance our understanding of the mechanism of amyloid formation.

Mechanical stress accelerates amyloid formation

Various mechanical stresses, such as agitation, fluid flow, and ultrasonication, also accelerate amyloid formation by breaking supersaturation. Among them, the agitator, which is readily available in the laboratory, enhances the apparent mean-free path of monomers in solution. The increase in the probability of intermolecular interactions by increasing the collision frequency and protein concentrations at the air-liquid interface under agitation generally accelerates protein aggregation. In addition, gyrating beads also accelerate amyloid formation depending on the hydrophobicity and other properties of the bead surface60. The addition of stainless-steel wire into sample solution reportedly accelerated amyloid formation of prion protein (PrP)61. Recently, silica nanoparticles (~50 nm) increase the local concentration of substrate, partly due to electric attraction and enhance amyloid nucleation of PrP62. Thus, stirring of the solution increases the collision frequency, air-liquid interface, and interaction with bead surface, which effectively accelerates amyloid formation because of surface denaturation and hydrophobic interactions between denatured proteins63.

In vivo, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and vascular flows are torrents at the microscale64. Flow through a narrow path has been reported to accelerate Aβ and other protein aggregation by shear force and extensional flow force14. Microfluids have aided LLPS research by clarifying the thermodynamics, kinetics, and other properties of condensates, such as the diffusion coefficient and saturation concentration of a phase transition65. Solutions of these proteins aggregate even at lower shear rates in the presence of certain surfaces, indicating that the combination of flow and surfaces may be crucial for amyloid formation. More recently, it has been found that commercially available peristaltic pumps can generate large shear stress (>~200 Pa) in liquids, triggering efficient destruction of supersaturation66.

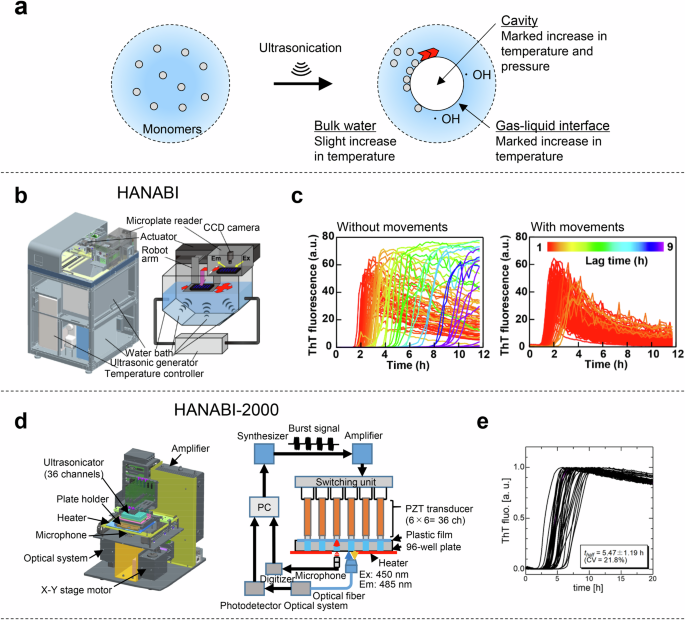

Ultrasonication is one of the most efficient methods for promoting amyloid formation67,68. Cavitation bubbles generated by the negative pressure of ultrasonic waves grow and collapse rapidly (Fig. 4a), causing an extremely high-temperature region of >10,000 K within the bubbles69. The ultrasonic cavitation bubbles act as catalysts for nucleation. To explain the marked frequency- and pressure-dependent nucleation, a theoretical model was proposed in which monomers are trapped on the bubble surface during growth and highly condensed during bubble collapse (Fig. 4a). Thus, the hydrophobic air-liquid interface is a scaffold for the formation of amyloid fibrils, and local condensation and heating play a major role in promoting amyloid nucleation.

a A model of reaction field around the cavities and radicals of water molecules formed after the disruption of cavitation bubbles under ultrasonication. b The HANABI system produces the ultrasonic wave in a water bath, the plate is moved sequentially along the x-y axis and the 96 wells are ultrasonicated uniformly. c Performance of HANABI with β2m. Amyloid formation was monitored by ThT fluorescence. 96-well microplate containing 0.3 mg/mL β2m, 100 mM NaCl and 5 μM ThT at pH 2.5 was ultrasonicated in repeated cycles of 1-min ultrasonication and 9-min quiescence without (left) and with (right) plate movements at 37 °C. The figure was reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 from Umemoto et al.10. d A 3D schematic illustration of the HANABI-2000 system (left) and a block diagram of the control units (right) of HANABI-2000. e The kinetics of β2m amyloid formation (n = 36) monitored by ThT fluorescence under ultrasonication. Reproduced with permission from ref. 11.

Although both ultrasonication and agitation can be effectively used to induce amyloid formation and propagation (Table 1), ultrasonication efficiently fragments the amyloid fibrils into short-dispersed fibrils and enables the identification of seeds with a detection limit of 10 fM70. Ultrasonication markedly alters the energy landscape of an aggregation reaction by ultrasonic cavitation. Under agitation, the metastable region is narrower than under quiescence, indicating that the agitation shifts the metastable/labile boundary downward (Fig. 1b), whereas the labile/amorphous boundary is hardly affected. Ultrasonication not only shifts the metastable/labile boundary downward but also shifts the labile/amorphous boundary upward. Amyloid formation can be promoted by imparting physical stress, such as mechanical and shear force, and an air-liquid interface, which are considered risk factors for various types of protein aggregation disorders by breaking supersaturation.

Development of equipment to amplify amyloid fibrils and accelerate amyloid nucleation in vitro

To amplify amyloid fibrils efficiently, an ultrasound-based amyloid amplification method, a PMCA method, was developed for the early diagnosis of prion disease in 2001 (Table 1)4. Amyloid fibrils are fragmented into small pieces and then they are amplified depending on seeds by the addition of monomers as substrates under ultrasonication. By repeating this reaction cycle, it is possible to amplify and detect abnormal conformations of prion protein (PrPSc). In addition, amyloid fibrils in CSF from Parkinson’s disease patients5,71,72 and oligomers in CSF from Alzheimer’s disease patients73 were amplified using PMCA.

An RT-QuIC method based on agitation was developed by Atarashi et al. (Table 1)7. By agitation of the solution, it is possible to detect a small amount of PrPSc in CSF from Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease patients7. The diagnosis of prion diseases, as well as synucleinopathies and tauopathies, has been improved using the RT-QuIC method74. The αSyn-PMCA assay based on agitation (also known as αSyn-RT-QuIC) can discriminate CSF samples from patients with Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy5. By combining immunoprecipitation and RT-QuIC methods (IP/RT-QuIC), pathogenic α-syn seeds were detected in the serum of individuals with synucleinopathies8. More recently, Micro-QuIC, an acoustofluidic platform, enables the rapid and sensitive detection of chronic wasting disease9. Thus, the PMCA and RT-QuIC methods and their applications essentially amplify amyloid fibrils using the seeds as a template. On the other hand, the HANABI method not only amplifies amyloid formation depending on seeds but also promotes spontaneous amyloid formation by accelerating nucleation.

A HANABI instrument was developed by combining a water bath-type ultrasonicator and microplate reader (Fig. 4b and Table 1)10. To assess the performance of the HANABI system, the amyloid formation of β2m was examined in 96-well plates with cycles of 1 min of ultrasonication and 9 min of quiescence (Fig. 4c). Without plate movements, the mean ± S.D. and coefficient of variation (CV) values of the lag time were 6.0 ± 4.0 h and 67%, respectively, and with plate movements, the amyloid nucleation synchronized with a mean ± S.D. and CV of 2.0 ± 0.4 h and 20%, respectively. In a clinical trial, the HANABI system was used to amplify and detect seeding-active αSyn aggregates from CSF, and the correlation between seeding activity and clinical indicators was investigated75. The seeding activity of CSF from Parkinson’s disease patients was higher than that of control patients.

In addition, the HANABI system was also employed to accelerate the crystallization of hen egg white lysozyme solution76. Ultrasonication has previously been shown to be useful for accelerating protein crystallization76,77. Extensive ultrasonication with repetitive pulses using HANABI produced numerous small, homogeneous crystals by breaking supersaturation.

However, the acoustic field of the original HANABI system could not be the same because of changes in temperature and distribution of dissolved gases in a water bath. To improve the reproducibility and controllability of the amyloid-fibril assay, a HANABI-2000 system with an optimized sonoreactor was constructed by removing the water bath, and a single rod-shaped ultrasonic transducer with a resonant frequency of 30 kHz was installed in each sample well of a 96 half-well plate (Fig. 4d)69. Amyloid formation of β2m was synchronized across 36 solutions by controlling the voltage and frequency of the driving signal applied to each transducer (Fig. 4e). The mean ± S.D. and CV values of the lag time were 5.47 ± 1.19 h and 21.8%, respectively.

Clinical trials using HANABI-2000

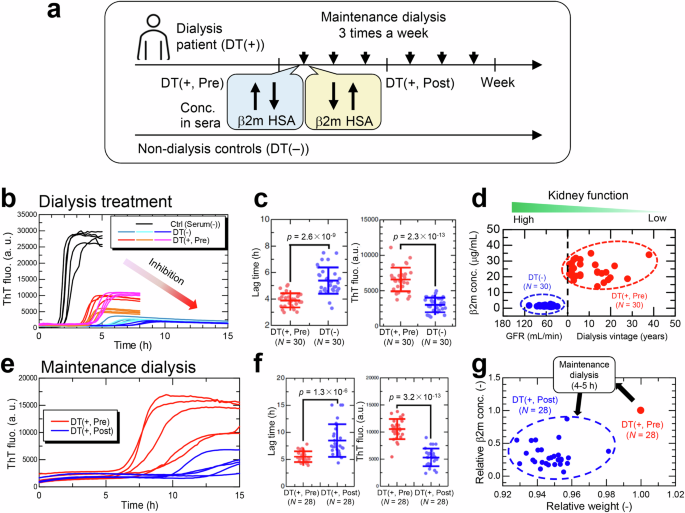

HANABI-2000 was used to elucidate the pathogenesis of dialysis-related amyloidosis (DRA) with a patient’s sera in terms of proteostasis and molecular crowding. The pathology of DRA is characterized by the deposition of β2m amyloid fibrils in the peritenons and synovial membranes of the carpal tunnel after long-term hemodialysis78,79,80. Although three β2m mutants related to amyloidosis have been reported: D76N81 and P32L82 in non-dialysis patients, and V27M in a DRA patient83, DRA is caused by wild-type β2m, indicating that a high concentration of serum β2m and long dialysis vintage (i.e., long period on dialysis) are major risk factors for DRA (Fig. 5a, d)78. However, the fact that patients with these risks do not always develop DRA84 suggests the presence of additional risk factors.

a Illustration of HANABI-2000 experiment using sera from dialysis patients (DT(+, Pre), DT(+, Post)) and non-dialysis controls (DT(−)). Sera were collected from identical dialysis patients before (DT(+, Pre)) and after (DT(+, Post)) a single maintenance dialysis. b Representative kinetics with sera collected from non-dialysis controls (DT(−)) and dialysis patients (DT(+, Pre)). Control (Serum(−)) does not contain sera and forms amyloid fibrils without inhibitory effects of sera. c The effects of dialysis-treated and non-dialysis-treated sera on β2m amyloid formation were compared in terms of the lag time (left) and ThT fluorescence (right). P-values were calculated by the unpaired one-sided t-test. d β2m concentrations in non-dialysis control group (DT(−)) and dialysis patient group (DT(+, Pre)). In the non-dialysis group, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is used as an index of kidney function. e Amyloid formation of β2m with 5% (v/v) sera from identical dialysis patients before (DT(+, Pre)) and after (DT(+, Post)) a single maintenance dialysis. f The effects of sera with and without maintenance dialysis on amyloid formation. g Effects of maintenance dialysis on serum β2m concentration and body weight of dialysis patients before (DT(+, Pre)) and after (DT(+, Post)) maintenance dialysis. Relative changes in the two parameters are shown compared to their values before maintenance dialysis. The figures were modified under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY license from Nakajima et al.49.

At first, to examine the effect of dialysis vintage, sera receiving different periods of hemodialysis therapy were compared with not receiving hemodialysis therapy (Fig. 5b). These two types of sera inhibited amyloid formation, but the degree of inhibition was markedly different between the two groups, indicating that dialysis patients are at higher risk for amyloid formation (Fig. 5c). Subsequently, the effects of maintenance dialysis three times a week (Fig. 5a) were examined (Fig. 5e). The inhibitory effects of serum were restored by the maintenance dialysis (Fig. 5f), indicating that long-term dialysis deteriorated the inhibitory effects of serum (Fig. 5b, c), whereas maintenance dialysis ameliorated the inhibitory effects (Fig. 5e, f). Importantly, concentrations of serum components except β2m, which is eliminated in sera by more than 50% (Fig. 5g), transiently increase with maintenance dialysis due to expulsion of water (usually 5% of body weight).

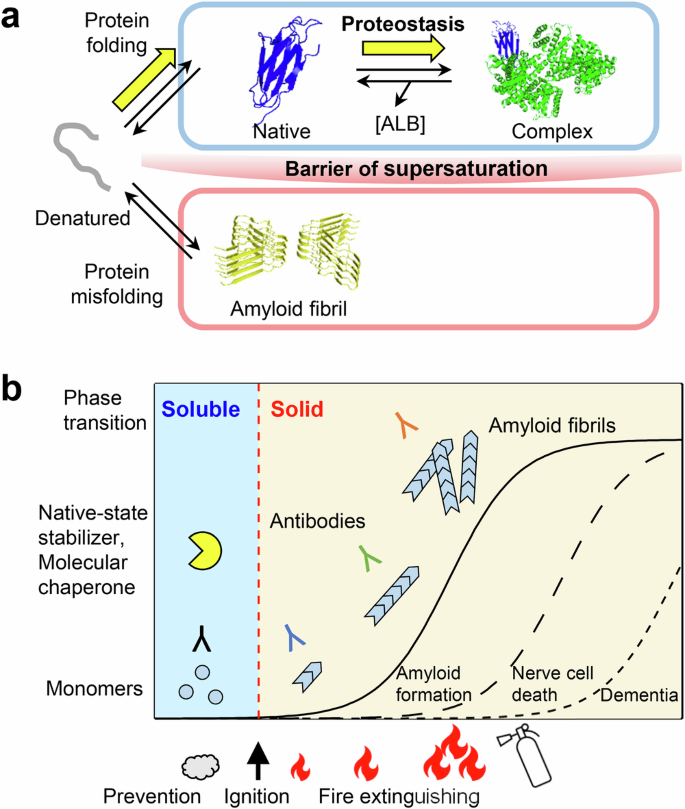

The relationship between serum components and amyloidogenic potential monitored by HANABI-2000 suggested that serum albumin has a role in inhibiting amyloid formation of β2m. A model of β2m amyloid formation focusing on serum albumin suggests that amyloid formation is inhibited by forming a complex with a biological factor and maintaining the supersaturated state (Fig. 6a). The concentration of the unfolded state, a precursor of amyloid formation, is reduced by binding to serum albumin.

a Schematic model of amyloid fibril (PDB ID, 6GK3) formation from monomeric β2m (PDB ID, 2D4F) in the presence of serum albumin (PDB ID, 1AO6). Amyloid formation is prevented by a barrier of supersaturation, and the HANABI system is important for identifying innate factors that maintain healthy proteostasis. Molecular diagrams were created using PyMOL Molecular Graphics. The figures were modified under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY license from Nakajima et al.49. b From a physicochemical perspective, amyloid formation is a phase transition from soluble to solid states that is limited by supersaturation in the model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s disease pathological cascade95. Therapeutic strategies that reduce the degree of supersaturation by measuring the risk of amyloid “ignition” may be more effective than “extinguishing” amyloid elongation49.

The combination of supersaturation-limited amyloid formation and interactions with native-state stabilizers such as serum albumin or small pharmacologic inhibitors such as tafamidis, which selectively stabilizes transthyretin (TTR) tetramer85 and shift the folding/unfolding equilibrium. Moreover, to inhibit the production of TTR, an RNA interference therapeutic agent, patisiran, was introduced86. While reducing serum β2m concentration may be an effective way to prevent DRA, maintaining serum albumin at a healthy level is a proteostasis strategy to prevent DRA87.

Several clinical trials have shown that symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease are alleviated using monoclonal antibodies against amyloid β peptides88,89. However, the supersaturation-limited nucleation-growth mechanism suggests that ‘extinguishing’ the growing amyloid fibrils is not easy (Fig. 6b). Amyloid fibrils dissolve when the bulk solute concentration is below the solubility limit90,91. Serum albumin is less specific, but would reduce the risk of amyloid nucleation by preventing amyloid ‘ignition’ rather than extinguishing the ‘amyloid fire.’

Conclusions

Thus far, various methods have been developed to amplify amyloid fibrils and accelerate amyloid nucleation by applying mechanical stresses. In addition, the effects of solvation and macromolecular crowding modulate the degree of supersaturation. Although there are other factors, such as temperature, pH, and pressure, that contribute to the stability of monomer protein and amyloid fibrils, amyloid formation will be accelerated by combining these mechanical stresses and solvent conditions. The same driving forces, such as hydrophobic, electrostatic, and van der Waals interactions, simultaneously promote not only protein folding but also amyloid formation, through the intramolecular and intermolecular interactions, respectively33,92. Amyloid formation is a phase transition from soluble to solid states prevented by the barrier of supersaturation and occurs above the solubility limit coupled with the breakdown of supersaturation (Fig. 6a)93. A relationship between reversible protein unfolding and supersaturation-limited amyloid misfolding has been postulated92. The law of mass action shifts the monomer equilibrium toward the unfolded state, thus allowing amyloid formation even under physiological conditions where only small amounts of unfolded precursor are present upon the breakdown of the supersaturation. The HANABI-2000 system is useful in the diagnosis of amyloidosis by rapid detection of seeds and the possibility of further early diagnosis by monitoring the risk level94, and advance understanding of biological reactions based on supersaturation.

Responses