Rapid on-site amplification and visual detection of misfolded proteins via microfluidic quaking-induced conversion (Micro-QuIC)

Introduction

Protein misfolding diseases, including prion diseases (also known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies [TSEs]), Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s, are a class of progressive neurodegenerative disorders that affect both animals and humans. The development of point-of-care (POC) diagnostic technologies for the accurate detection of misfolded proteins is essential for early diagnosis and intervention in these diseases. Prion diseases, a subset of protein misfolding diseases, are 100% fatal and impact both humans and animals, with examples including Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) and fatal familial insomnia in humans, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE; also known as “mad cow disease”) in cattle, scrapie in sheep, and chronic wasting disease (CWD) in deer and elk1,2,3.

These diseases are caused by the accumulation of infectious protease-resistant forms of the prion protein (PrPRes) within the central nervous system (CNS). A concerning feature of PrPRes is that the infectious proteins withstand traditional methods of decontamination (e.g., standard autoclaving) and can remain infectious within a given environment for years4,5,6. Once formed, PrPRes interacts with native cellular prion protein (PrPC), inducing misfolding events that ultimately lead to the creation of additional PrPRes and related protein fibrils and plaques7. After onset, aggregated PrPRes propagates throughout the CNS, killing neurons and supporting cells, and eventually cascading to death.

TSEs are 100% fatal and typically have variable incubation times depending on the species impacted and underlying genetic factors2. The native cellular form of PrPC is highly conserved across mammalian species, thus the potential exists for cross-transmission of PrPRes, the most notable example being the outbreak of variant CJD in humans after consumption of BSE contaminated meat products throughout the United Kingdom in the late 1980s and 1990s8. This research focuses on the development of a novel misfolded protein detection device using CWD as a model, since CWD shares similarities with human protein misfolding diseases and samples from wild white-tailed deer are readily accessible. There is growing concern that CWD will cross multiple animal and human species barriers, leading to sporadic outbreaks of prion diseases in humans or livestock. With the global spread of CWD to cervid populations, including North America, Scandinavia, and South Korea, the number of exposure events to infectious CWD prions in both animals and humans is predicted to increase substantially9. Therefore, there is an urgent need for on-site diagnostic tools that can rapidly and accurately detect CWD-causing prions, ultimately benefiting the broader field of protein misfolding disease diagnostics.

Conventional diagnostic methods for CWD, such as antibody-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and immunohistochemistry, are both time-consuming and expensive, and require substantial training and expertise to operate10. Moreover, their diagnostic sensitivity is limited due to the inability of commonly used antibodies to distinguish between PrPC and PrPRes11, thus necessitating complicated enzymatic, chemical, and/or heat digestion to enrich PrPRes. Therefore, a definitive diagnosis of CWD often requires post-mortem histopathological examination12.

A promising development in protein misfolding disease diagnostics involves the use of ultrasensitive seeding assays that facilitate the in vitro amplification of PrPRes13. Real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC)14 and protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA)15 both exploit the ability of PrPRes to induce PrPC to misfold cyclically, forming quantifiable in vitro aggregates of protein fibrils (Fig. 1a)16. To achieve this, RT-QuIC utilizes shear force while PMCA (in its original form) utilizes sonication to mechanically fragment the PrPRes fibrils into smaller nucleation sites. An important feature separating RT-QuIC from traditional PMCA is that RT-QuIC conducts protein amplification using a recombinant prion protein substrate that does not produce infectious PrPRes as the result of the assay. Alternatively, PMCA typically utilizes native hamster brain as a substrate, thus producing native misfolded PrPRes throughout a given experiment. Another defining feature separating the assays is that RT-QuIC results are produced using standard fluorescent plate readers that measure Thioflavin-T (ThT) excitation levels with great sensitivity throughout a given experiment, whereas traditional PMCA requires multiple rounds of Western blotting and gel-image-based protein quantification. For these reasons, RT-QuIC is gaining more widespread usage for CWD research and diagnostics17,18,19,20.

a Kinetic profile of the misfolded PrP, showing Thioflavin T fluorescence intensity as an indicator of prion amplification. The curve progresses from a lag phase to a rapid exponential increase, reflecting prion-induced rPrP misfolding, and culminates in a plateau phase. b Misfolded chronic wasting disease (CWD) prion seeds originating from biological samples are added to rPrP solutions and injected into a microfluidic device. This creates a liquid-air interface between the main channels and side channels. The application of high frequency sound waves (4.6 kHz) induces vibration of the liquid–air interface to create a vortex current. Acoustic waves are applied to these solutions for approximately 3 h while being incubated at 40 °C. If present, PrPRes induces conformational changes of the rPrP. Resulting products are labeled with Thioflavin T, which can be detected under fluorescent microscope (excitation wavelength ~450 nm, emission wavelength ~480 nm.). c Schematic of microfluidic-QuIC device. Double layers of PDMS devices are bonded to the thin glass slides. Mineral oil is injected between the two layers of PDMS to prevent solution evaporation. A piezoelectric transducer is attached on the back of the glass slide. d Photograph of a microfluidic-QuIC device.

While RT-QuIC boasts high sensitivity, its application for in situ or “on-the-spot” CWD diagnosis remains curtailed by several factors. For example, it requires bulky and expensive equipment which can cost approximately $25,000–40,00021. Moreover, manual handling of costly reagents increases the risk of contamination as well as reagent waste. Thus, there is a critical need to develop an in situ assay platform that confers rapid diagnosis of CWD in a fully automated manner while minimizing equipment size, cost and reagent usage.

In response to these challenges, microfluidics offers a promising avenue. Specifically, transitioning from macroscopic platforms to microfluidics can introduce numerous advantages for diagnostic application, such as lower reagent requirement22, increased specific surface-area-to-volume ratios23, biohazard containment24, and heightened heat and mass transfer rates25. While some microfluidic platforms have shown potential in reducing assay time26, they tend to suffer from an inherently low Reynolds number, which limits the mass transfer to a diffusion-limited regime27. Moreover, the use of elaborate pumps limits their application in on-the-spot diagnosis28.

Within the realm of microfluidics, both active and passive micromixers have been developed including, inertial29, acoustofluidic30,31, electrokinetic32, and magneto-hydrodynamics micromixers33. Among these, acoustofluidic micromixers have proven to be a powerful tool due to the high mixing index, low-cost of operation34, biocompatibility35, portability and the contact-free nature of the technology36. Specifically, lateral cavity acoustic transducers (LCATs) have been widely investigated37,38,39. Given these developments in acoustofluidic transduction mechanisms, we hypothesized that acoustofluidic microstreaming would generate sufficient shear stress to fragment non-covalent interaction between amyloid-enriched prion fibril subunits, laying the groundwork for a new platform for the rapid amplification of misfolded proteins.

Herein, we present an on-the-spot diagnostic platform integrating an assay similar to RT-QuIC, harnessing the power of acoustofluidic mixing for PrPRes and PrPC. Our device, shown in Fig. 1b–d, comprises a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-covered glass coverslip with reagent mixing facilitated by lateral cavity acoustic transducers, where arrays of dead-end side channels capture air bubbles which function as a vibrative membrane (Fig. 1b). Upon the application of a high frequency soundwave (4.6 kHz), the liquid-air interfaces resonate and the resulting acoustic field energizes the bulk liquid and produces a net force perpendicular to the bubble interface and out the end of the cavity40. The resulting acoustic streaming enhances the collision between PrPRes and PrPC as well as fragmentation of PrPRes into smaller pieces, which in turn result in the multiplication of active seeds for the PrPRes nucleation. LCATs are well suited for this application due to the simplicity in fabrication, tunability of mixing rate and high mixing index36. By combining the reagent microstreaming induced by the acoustofluidic micromixer and the quaking-based prion fibril amplification, we demonstrate that our method drastically reduces the amplification time from the 15 h typically required by RT-QuIC assays to 3 h41. Furthermore, Micro-QuIC can be integrated with a gold-nanoparticle-based aggregation assay21, eliminating the need for bulky auxiliary detection modules. The Micro-QuIC device features advantages such as simplicity of use, automation, low cost, and portability, which are necessary for the future development of an automated all-in-one, on-chip amplification toolkit for on-the-spot diagnosis of protein misfolding diseases.

Methods

Materials

All materials were used as purchased unless noted otherwise. SU8 2050 (Microchem Inc.), silicon wafer (Siegert Wafers), SU8 developer solutions (Microchem Inc.) microscope cover glass (24 × 50 mm, Globe Scientific Inc.), piezoelectric transducers (7BB-27-4L0, Mouser electronics), ThT, 100 kDa Pall MWCO filter, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), sodium chloride (NaCl), phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and trimethoxysilane were purchased from Sigma Milipore. Fluorescent microspheres (FCDG006) were purchased from Bangs Laboratories Inc. PDMS and curing agent were obtained as SYLGARD®184 silicone elastomer kit from Dow Corning.

Preparation of recombinant substrate

The synthesis and purification of recombinant hamster PrP (HaPrP90-231) followed the methods of ref. 17. In brief, a truncated form (amino acids 90–231) of the Syrian hamster PRNP gene was cloned into the pD431-SR expression vector (ATUM, Newark, CA, USA) and was expressed in Rosetta (DE3) E. coli to synthesize the substrates. Subsequent purification and quality assessments followed ref. 17.

Tissue preparation

Tissue preparation followed the methods of ref. 21. In brief, 10 white-tailed deer tissues (5 CWD negative and 5 CWD positive) were obtained from white-tailed deer through collaboration with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and their CWD status was independently confirmed using the Bio-Rad TeSeE Short Assay Protocol (SAP) Combo Kit (BioRad Laboratories Inc., CA, USA) as well as RT-QuIC17. White-tailed deer retropharyngeal lymph nodes (RPLNs) and palatine tonsils were homogenized in PBS (10%w/v) with 1.5 mm zirconium beads with a BedBug Homogenizer (Benchmark Scientific, Sayreville, NJ, USA) on max speed for 90 s.

RT-QuIC for tissues and spontaneous misfolding of recombinant prion protein

For QuIC analysis, a master mix was prepared following specifications: 1× PBS, 1 mM EDTA, 170 mM NaCl, 10 μM ThT, and 0.4 mg/mL rHaPrP. The 10% tissue homogenates were further diluted 100-fold in 0.1% SDS/PBS/N2 (final tissue dilution: 0.1%), and 2 μL of the diluent were added to each well containing 98 μL of RT-QuIC master mix. Spontaneous misfolding of recombinant prion protein was done similarly but with unfiltered recombinant proteins and reagents. For these reactions, no infectious seed was necessary because runs were performed for longer than 72 h, leading to spontaneous formation of misfolded protein. The spontaneously misfolded material was used to seed reactions for both Micro-QuIC and RT-QuIC. Plates were amplified on a FLUOstar® Omega plate reader (BMG Labtech, Cary, NC, USA) (42 °C, 700 rpm, double orbital, shake for 57 s, rest for 83 s). Fluorescent readings were taken at ~45 min increments.

Preparation of microfluidic device and operation

The PDMS-based microfluidic device fabrication was performed using soft-lithography as described previously. Master molds were prepared on 4-inch silicon wafers by spin coating (Model CEE-100, Brewer Science Inc.) SU8 2050 to a height of 50 µm. Following the coating process, a pre-baking step was performed before UV-light exposure through a film mask with the requisite design, onto the SU8 coated silicon wafer for a duration of 12 s (MA6, Karl Suss). A post-baking step was performed before the SU8 development process. SU8 development was performed by gently washing the wafer in the developer solution for 3 min. Finally, the Si-wafer was silanized for 30 min with trimethoxysilane. PDMS-based microfluidic chips were produced by heat curing (90 °C for 3 h) PDMS with a curing agent mixture (10:1) on the master mold Si-wafer. Cured PDMS was peeled and cut into individual chips. Holes were punched at respective inlets and outlets using a 1 mm biopsy puncher (Acuderm Inc.) before bonding the PDMS to microscope cover glass. The bonding procedure was performed by treating both cover glass and the PDMS with a high-frequency generator (BD-10A, Electro-Technic Inc.) for 1 min. The microfluidic devices were heated for 2 h at 65 °C to help with the bonding process. For the fabrication of the outer PDMS casing, a master mold was fabricated by attaching a rectangular mold (3 cm × 1.5 cm × 0.5 cm) on a 4-inch silicon wafer, followed by silanization with trimethoxysilane for 30 min. Outer PDMS casing was fabricated by heat curing the PDMS master mix at 90 °C for 3 h. Once cut into individual chip size, holes were punctured at respective inlets and outlets using a 1 mm biopsy puncher. Outer PDMS casing was bonded to a microfluidic device by aligning the inlets and outlets. Mineral oils were injected in between the microfluidic PDMS channel and the outer PDMS casing. Finally, piezoelectric transducers were attached at the back of the device using epoxy glue. The photograph of a final assembled device can be seen in Fig. 1d. Before conducting the amplification experiments with recombinant PrP samples, all of our devices were experimentally tested with 0.005% fluorescent polystyrene microspheres (1 µm) to determine the optimized working frequencies of piezoelectric transducers to achieve uniform mixing. Based on these tests, 4.6 kHz was determined to be the working frequency for all our micro-QuIC devices; all the amplification experiments were conducted at this frequency. To track aggregated PrP, fluorescent images were obtained every 30 min for approximately 3 h using laser excitation at 445 nm. The fluorescence intensity was measured by modifying the corrected total cell fluorescence measurement.

Quantitative fluorescence analysis of amyloid fibril formation in microfluidic channels

For the analysis of the fluorescent images, we utilized ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA) to measure the area occupied by fluorescent aggregates above a predetermined intensity threshold. This approach is similar to the corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) method, which is commonly used for quantifying fluorescence signals in cellular imaging. The CTCF is calculated by subtracting the background fluorescence from the total fluorescence signal within a defined region of interest (ROI). In our study, the ROI was the entire field of view of the microfluidic channel. The fluorescence intensity threshold was established based on control experiments with non-aggregated PrP samples to ensure that the measured area represented the presence of amyloid fibrils. The total area of fluorescent aggregates above the threshold was normalized to the total area of the field of view to obtain a relative measure of fibril formation.

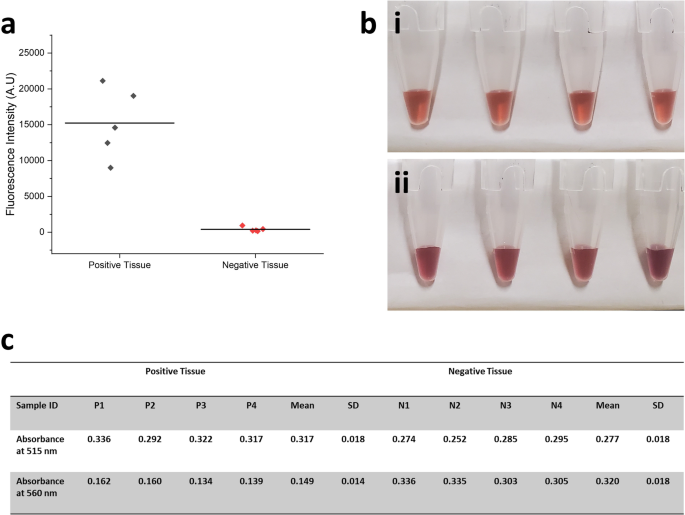

Gold-nanoparticle-based detection

Gold-nanoparticle-based prion detection followed the methods of ref. 4. In brief, 2.45 nM 15 nm citrate capped gold nanoparticles (Nanopartz™, Loveland, CO, USA) were buffer exchanged to low concentration phosphate buffer (10 mM Na2HPO4 (anhydrous), 2.7 mM KCl, 1.8 mM KH2PO4 (monobasic)). After the amplification, protein solutions (n = 4) were diluted by twofold in 1× PBS with the addition of final concentrations of 1 mM EDTA, 170 mM NaCl, 1.266 mM sodium phosphate. Finally, 20 μL of the dilute protein solution was then added to the 180 µL AuNP solution and left to react at room temperature (RT) for 30 min. The color changes were observed both by naked eye and colorimeter (FLUOstar® Omega plate reader, BMG Labtech, Cary, NC, USA) at 515 and 560 nm wavelength.

Additional statistical information

GraphPad Prism version 9.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA, (www.graphpad.com) was used for conducting statistical analysis. Three technical replicates were used to demonstrate the potential application of AuNP on spontaneously misfolded rHaPrP. Four technical replicates were used for testing CWD prions using AuNP and RT-QuIC, respectively, for each animal. RPLN and/or palatine tonsil tissues from 5 positive and 5 negative animals were included in this study. The one-tailed Mann–Whitney unpaired U-test (α = 0.05) was used to test the average difference for all parameters of interests between samples.

Animal research statement

No deer were euthanized specifically for the research conducted herein and all tissues were secured from dead animals or loaned for our analyses. Thus, the research activities presented herein are exempt from review by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (as specified https://research.umn.edu/units/iacuc/submit-maintain-protocols/overview). White-tailed deer were euthanized for annual culling efforts to control the spread of CWD in Minnesota following Minnesota Department of Natural Resources state regulations and euthanasia guidelines established by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists42.

All methods and all experimental procedures carried out during this research followed University of Minnesota guidelines and regulations as approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee under protocol #1912-37662H. This study was also carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Results

Microfluidic quaking-induced conversion (Micro-QuIC) device

In this work, we sought to combine the active mixing benefits of acoustic technology with quaking induced prion amplification. To that end, Fig. 1c, d provide a schematic and photograph of the assembled Micro-QuIC device, respectively. The foundation of the acoustofluidic device is a thin glass coverslip that serves to transfer the vibrational energy from the acoustic transducer (shown in the figure) into the PDMS channels via flexural waves that travel out from the transducer and along the glass coverslip43. The primary design of the microfluidic channel geometry consists of lateral cavity structures which capture air cavities upon injection of reagents. The resulting liquid-air interface serves as an oscillating membrane in response to vibration from the transducer, producing acoustic streaming in the channel to agitate the samples40.

The lateral cavity structure is designed with a channel width of 300 μm and a height of 100 μm and is repeated in 16 sets along the length of the main channel. Over the microfluidic PDMS layer, an outer PDMS channel creates a void with mineral oil, preventing heat-mediated evaporation of the reagent. The sample reagents are introduced into the main channel through the inlet while incubating the entire device at 40 °C. A piezoelectric transducer attached at the back of the glass slide generates an acoustic field to induce vibration of the liquid–air interface. This creates micro-vortex streaming in the main channel, which accelerates both the collision between PrP particles and the shear-induced fragmentation of PrPRes fibrils. The collision between PrP particles in turn accelerates conversion of PrPc to PrPRes, while the fragmented PrPRes serves as a secondary nucleation increasing the number of reactive fibril ends and promoting fibril elongation. As the number of fibrils increases, a fluorescent dye, ThT, specifically binds to the amyloid aggregates which can be observed under a fluorescent microscope.

Device characterization

Prior to prion amplification, we initially tested our device’s micro-vortex streaming capabilities using fluorescent microparticles. As shown in Fig. 2a, b, fluorescent microparticles showed vigorous circular motion upon application of an input bias of 10 Vpp at 4.6 kHz. The streaming velocity primarily depends on two parameters: frequency and voltage. To determine the frequency at which the LCAT generated the strongest acoustic streaming effect, the AC frequency was swept from 1 kHz to 7 kHz with a 1 kHz increment at 5 Vpp. Our experimental result indicated that the strongest acoustic streaming effect was observed in the range of 4–5 kHz. This finding is in agreement with the manufacturer’s specifications, which suggest that the piezoelectric transducer operates optimally at a resonant frequency of 4.6 kHz, expected to generate the highest acoustic power. Outside the resonant frequency of the piezoelectric transducers, the streaming velocity drastically decayed (Fig. 2c). Therefore, the AC bias was maintained at the resonant frequency for all of our experiments. The device was further characterized by applying different driving voltages to the piezoelectric transducer. Figure 2d shows the mixing performance with the different driving voltages at a frequency of 4.6 kHz. The results show that as the driving voltage of the piezoelectric transducer increased, the mixing efficiency was increased40.

a Fluorescent micrograph of microparticles when voltage bias was applied to the piezoelectric transducer. b Fluorescent micrograph of microparticles with an input bias of 10 Vpp of 4.6 kHz. The trajectory of microparticle motion is illustrated in white arrows. c Relationship between the applied frequency versus the average velocity of microparticles (n = 5). d Relationship between the applied voltage bias versus the average velocity of microparticles (n = 5).

On-chip prion amplification with Micro-QuIC

Next, we established the experimental condition for Micro-QuIC. Initially, a spontaneously misfolded rHaPrP (positive control) was spiked in a master mix consisting of 1× PBS, 1 mM EDTA, 170 mM NaCl, 10 μM ThT and rHaPrP ranging from 0.1 mg/mL to 0.4 mg/mL. In this study, we kept the rHaPrP concentration at 0.4 mg/mL for both RT-QuIC and Micro-QuIC all the times unless stated otherwise, since this condition gave excellent fluorescence. Both positively (misfolded, n = 5) and negatively (non-misfolded, n = 5) seeded master mixes were injected in a Micro-QuIC device and amplified for 180 min. Here, the 10 Vpp AC bias at a frequency of 4.6 kHz was applied for 30 s intervals with 30 s of rest. The fluorescent images were taken every 30 min to follow the amplification process over 180 min (Fig. 3a). For the quantification of fluorescent intensity, we analyzed fluorescent particles in the field of view by thresholding. Both the number of fluorescent particles and their size increased from the positively seeded sample, indicating successful prion amplification, while there was no measurable change in fluorescence intensity in the negatively seeded sample). Based on our result, we have successfully demonstrated that prion amplification can be achieved in 180 min (Fig. 3b) which is 5 times faster than conventional RT-QuIC (Fig. 3c). In examining the amplification kinetics across a series of serially diluted positive samples, we observed that Micro-QuIC accelerated the amplification process, achieving a rate approximately five-fold faster on average at all tested concentrations. This rapid amplification by Micro-QuIC, however, was limited by its sensitivity threshold; amplification was consistently observed only down to a 10−5 dilution. In contrast, RT-QuIC was capable of amplifying samples with dilutions as low as 10−6, suggesting a more sensitive detection limit (Fig. 3d). To validate the amplified prion fibrils, We employed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to examine the dimensions and morphology of amyloid fibrils amplified by Micro-QuIC. The characteristics observed were consistent with previously published data on fibrils amplified using conventional methods44,45,46 (Fig. 3e, f). As reported previously47, the fibrils from both samples were helical in shape with an average width of 25 nm which further validates that amplification products were equivalent in both methods.

a Fluorescent micrograph of aggregated prion particles when periodic mixing with 30 s interval was carried out by applying bias of 10 Vpp at 4.6 kHz from 0 min to 150 min. b Fluorescence intensity of prion particles amplified by the Micro-QuIC device over 300 min of amplification process (n = 5). The fluorescence intensity was measured by particle tracking algorithm. c Fluorescence intensity of prion particles amplified by conventional RT-QuIC method over 50 h. The concentration of rHaPrP was changed from 0.1 mg/mL (1×) to 0.4 mg/mL (4×). d Comparative analysis of the rate of amyloid formation (RAF) in serially diluted samples using RT-QuIC and Micro-QuIC, showing the relative amplification rate of Micro-QuIC and the sensitivity limit of detection down to a 10−5 dilution factor. e, f Morphology of prion fibrils amplified by Micro-QuIC device taken by TEM.

On-site prion amplification and visual detection via Micro-QuIC and gold-nanoparticle-based assay

Recognizing that Micro-QuIC can greatly accelerate rHaPrP misfolding and amplification kinetics, we then explored its potential of field-portable diagnostics of misfolded proteins using PrPCWD-positive and PrPCWD-negative white-tailed deer lymphoid tissues as model system. We prepared homogenates of independently confirmed CWD-positive and CWD-negative white-tailed deer medial retropharyngeal lymph nodes (RPLN) following methods as reported in ref. 17, then introduced them into Micro-QuIC devices along with the master mix. We tested positive (n = 5) and negative (n = 5) tissue samples. Each sample was incubated at 40 °C with periodic acoustic mixing as before for 3 h. End-point fluorescence measurement of the microfluidic channel showed that we were clearly able to distinguish CWD-positive and CWD-negative samples through the difference in fluorescence intensity (Fig. 4a). The significant reduction in assay time (~3 h) makes Micro-QuIC an attractive alternative to the current gold standard for CWD diagnostics.

a Fluorescent intensity measurement of independently confirmed CWD-positive (n = 5) and CWD-negative (n = 5) white-tailed deer medial RPLN tissue sample amplified through Micro-QuIC device. b Photo of optical-based misfolded PrP detection using gold nanoparticles (MN-QuIC) and c absorbance at 515 and 560 nm. Gold nanoparticle (AuNP)-based aggregation assay for the detection of amplified prion particles (n = 4). (i) PrPRes does not allow for bulk interactions with AuNPs and hence does not alter absorbance of AuNPs, while (ii) PrPC readily interact with the surface of AuNP to form aggregation that cause blue shift.

Christenson et al. previously reported the optical-based misfolded PrP detection system using gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), which eliminates the need for a bulky fluorescence detection module21. The mechanism of the AuNP-based assay involves the interaction between the nanoparticles and prion proteins. Non-misfolded haPrP have a net positive charge that adheres them to the negatively charged AuNPs, serving as a bridge between AuNPs thus causing aggregation. This aggregation leads to a blue shift in the plasmonic resonance of the AuNPs. Conversely, misfolded haPrP does not cause AuNP aggregation due to a lack of available haPrP for binding, and thus the sample retains the red color characteristic of normal AuNPs48,49,50. Further, nanoparticles have been shown to influence amyloid formation kinetics50,51,52,53,54 and enhance the speed and sensitivity of conventional RT-QuIC55. In conjunction with Micro-QuIC, the AuNP based detection system would provide a valuable tool towards a field deployable CWD testing platform. To verify the compatibility of Micro-QuIC and AuNP assays, tissue samples were first amplified in a microfluidic channel at 40 °C with periodic acoustic mixing for 3 h as before. The post-amplified mixture was drawn from the microfluidic channel and incubated with a gold nanoparticle reagent for 10 min. Upon addition of positive samples, the absorbance peak remained unchanged at 515 nm while the addition of negative sample absorbance peaks was shifted to a longer wavelength of approximately 560 nm, which showed itself as a clear visual distinction between CWD-positive and CWD-negative samples (Fig. 4b, c). This result is consistent with previous results using the AuNP assay, thus demonstrating that our Micro-QuIC assay is effectively amplifying PrPCWD associated with CWD-positive samples and producing negative results for CWD-negative samples. The integration of Micro-QuIC with nanoparticle-enhanced QuIC methods, such as Nano-QuIC or AuNP assay, suggests promising potential toward rapid, efficient amplification of misfolded proteins paired with a compact, visual detection method for point-of-care disease diagnostics.

Discussion

The historic vCJD outbreak in the United Kingdom following BSE prion exposure underscores the necessity for routine and effective prion disease surveillance strategies. It is within this framework that concern is escalating across North America, Scandinavia, and South Korea as CWD continues to spread within cervid populations that are distributed across expansive geographic regions and that are a common source of food, food supplement, or herbal medicine. Recent estimates indicate that venison from tens of thousands of CWD-positive cervids are unknowingly being consumed9, resulting in frequent exposure events to infectious prions and testing the human/cervid species barrier. For this reason, there is an urgent need to develop innovative diagnostic tools capable of the accurate, rapid, and “on-the-spot” detection of CWD. Our approach combines RT-QuIC amplification of CWD prions with an acoustofluidic micromixer for swift amplification of target misfolded proteins. We hypothesized that an acoustofluidic micromixer would exert high shear stress to PrPSc fibrils, including active fragmentation, which in turn serve as a secondary nucleation site to promote further elongation. Our strategy has successfully slashed the diagnosis time to approximately 3 h, a significant improvement over standard RT-QuIC.

We have further enhanced the utility of our approach by integrating AuNP-based visual detection method into our amplification strategy. This integration offers several benefits, notably making Micro-QuIC compatible with non-fluorescent based detection, eliminating the need for a bulky fluorescence detection module, and enabling the rapid, portable, and on-site diagnosis of misfolded proteins. Future work should include design updates that combine the AuNP readout system and Micro-QuIC amplification into a single chip to minimize user handling of samples. This would open up the potential for a field-deployable, POC testing platform, a development which could have far-reaching implications for protein misfolding disease diagnosis.

Our Micro-QuIC technology holds great promise for the rapid and visual identification of CWD-positive and CWD-negative lymph tissues following QuIC amplification. We chose RPLN and palatine tonsils collected from white-tailed deer for this study, as these tissues are ideal for early and accurate identification of CWD infection. Future analyses will focus on using Micro-QuIC for antemortem CWD diagnostics. RT-QuIC amplification protocols using samples acquired from living deer have recently been reported19,56,57 and these protocols could readily be combined with Micro-QuIC to provide rapid field-deployable antemortem tests of both wild and farmed cervids. While RT-QuIC assays already utilize kinetic readout for monitoring prion aggregation, our Micro-QuIC technology aims to complement this approach by offering advantages in speed and portability. The integration of acoustofluidic micro-mixing in our system may enhance the efficiency of prion detection, potentially allowing for more rapid identification of prion presence. Additionally, the compact design and rapid processing time of our Micro-QuIC platform make it a suitable candidate for field settings, where swift, real-time monitoring is crucial for disease management. Although our current study does not delve into the differentiation of disease stages or strains, the preliminary results suggest that the enhanced speed of Micro-QuIC could lay the groundwork for future investigations in these areas. Therefore, our technology is intended to complement, rather than replace, existing RT-QuIC approaches, by providing a more rapid and portable option for prion disease diagnostics. Moreover, it is possible that Micro-QuIC has utility as a food-safety test given the recent documentation of RT-QuIC-based detection of CWD in white-tailed deer muscles that are used for human and animal consumption58. More broadly, we posit that our Micro-QuIC assay has the potential to be a versatile “on-site” platform for detecting a variety of protein misfolding diseases where RT-QuIC and PMCA have been utilized, including scrapie in sheep, BSE in cattle, and CJD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s in humans59.

Responses