Estimation of median LC50 and toxicity of environmentally relevant concentrations of thiram in Labeo rohita

Introduction

Aquaculture is an important food-producing sector of the world that plays an important role to meet the food demands of ever increasing population over the time and is a rapidly growing source of high-priced water food species, frequently consumed as fresh products1,2. In Pakistan, total fish production reached 720.9 thousand metric tons during the year 2023–24 with an annual increase of 0.81%3. Labeo rohita (Rohu) is the dominant and commercially most important cultured species among the fresh water carps all around the world and globally, 72% of total carp production, Labeo rohita accounts for 15% of the aquaculture production4. Due to high consumer demand, better growth performance and sustainability, rohu is the most cultivated species among the major Indian carps in the polyculture system5. Labeo rohita is considered as a water quality index and bioindicator and a potent biomarker for the assessment of water quality contaminated with heavy metals6,7,8 or different chemicals9,10,11.

Aquatic organisms are under the influence of different environmental stress factors including pesticides12,13,14,15. These pesticides not only cause atmospheric pollution but also access water bodies via surface water, spray drift, draining and ground water resources leading to water contamination and thus, have severe negative effects on aquatic environments16,17,18,19,20. Tetramethyl thiuram disulfide (known as thiram) is broadly used in the agriculture industry due to its high efficacy and low cost. It is also used in the sugar pulp, paper industry, as an anti-slime agent and an accelerator to increase the process of vulcanization in the rubber industry21,22. Thiram enters the environment via pesticide spray on crops and in gardens, as well as eluents from the treatment plants of waste water and eventually enters into the soil and water food chains. Despite its many useful applications, excessive use of thiram causes severe pollution both in air and water and hence, becomes harmful to the organisms of land and water environments.

Thiram has a unique structural formula and thus it possesses two opposing effects: oxidative effect due to disulfide bridge (S-S) and second one is the reductive effects due to presence of thiol group (-SH) in diethyldithio carbamate anion which is formed during reduction process of thiram. Both these groups have their effects in immuno-stimulation, inflammation, cell death or apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction23. Thiram exposure is linked to a number of toxicological effects including neurotoxicity24, hepato-toxicity25, endocrine disruption26, genotoxicity27 and inhibition of enzyme reactions28 in rodents and fish. Moreover, it has been found in earlier published data that thiram cause different developmental deformities in the embryos of zebra fish like reduced eye pigment, yolk sac edema, curved spines, abnormal somites, disorders of tail and hatching defects29. Similarly, various ailments like hatching arrest, retardation of growth, bradycardia and abnormalities in the spinal curvature were observed in the thiram treated embryos of zebra fish30. Additionally, thiram inhibits the enzyme activity of aryl amine N-acetyltransferase-1 by interfering with the metabolism of aromatic amine xenobiotic compounds31. Predominantly, it has been found that thiram inhibit heat-shock protein 90 and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in avian growth plate chondrocytes in vitro32,33 and induce tibial dyschondroplasia in vivo34,35 in chicken. In addition to these effects, since thiram inhibits angiogenesis since it significantly (60%) inhibited C6 glioma tumor development and caused a 3–5-fold reduction in growth of metastatic Lewis lung carcinoma36, hence, it could be used in the pharmaceutical preparations for anti-angiogenic therapy of metastatic gastro-intestinal, neuroendocrine, colorectal and reproductive carcinomas37.

The humans are affected with thiram by eating the sprayed fruits, vegetables having its residues, directly exposed or by breathing in the contaminated air or by drinking the contaminated water. Thiram (25–500 mM) has been found to cause hemoglobin oxidation and heme degradation and leads to production of reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) as well as reduced the free radical quenching and metal reducing ability of human erythrocytes38. Moreover, it was quite evident that thiram caused dysfunction of the mitochondrial metabolic pathway and induced a dose- and time-dependent necrosis in the fibroblasts of human skin in vitro22. Hence, a strong relationship has been observed between the pesticides toxicity and the production and effects of reactive oxygen species39. The formation of these free radicals is the foremost causative factor of several diseases like cancer, cardiovascular diseases, rheumatoid arthritis and neuro-disorders40. NF-kB and hypoxia inducible factor are the key transcription factors that are inactivated due to thiram and thus, apoptosis is induced and peptide amidation is increased in the absence of NF-kB binding to DNA. Additionally, the oxidative stress brought-on by thiram increases the mitochondrial permeability41. Hence, despite recognizing the several harmful effects and published data on toxic effects of thiram on land and aquatic organisms, its deleterious effects have not been reported in the commonly found fish Labeo rohita affected with water contamination with thiram. Initially, we determined the LC50 value of thiram for Labeo rohita, since LC50 value of thiram for this fish has not yet been estimated. Then, the fish were exposed to different environmentally relevant sub-lethal concentrations of thiram to determine various genetic, biochemical and histo-pathological alternations in different organ tissues of Labeo rohita. These alterations in hemato-biochemical and histo-pathological parameters of the fish are important biomarkers to estimate the aquatic contamination in the apparently clean water that is not favorable for aquatic species and is thus inappropriate for animal and human consumption.

Methods

Fish housing and management

Healthy and active fish having a weight of about 180–200 g were obtained from commercial fish market and placed in clean and well oxygenated aquarium. The metrics of water chemistry were determined before the start of the trial and maintained during the whole duration of the experiment, to keep a comfortable environment for the fish. The water of the aquarium was maintained at a temperature of 20.5 °C, pH at 7.43 with a salinity level at 0.5 ppt, total dissolved solids (0.43 ppt), electrical conductivity (1.68 mS/cm), ammonia (0.5 mg/L) and dissolved oxygen at a level of 6.32 ppm. Food supply of commercially available fish feed containing crude protein (22% protein) and groundnut cake was offered to the fish in the form of pellets (2-3% of body weight) at twice every day. The siphoning of the residual feed and the fecal materials from the aquaria was done on regular basis to keep the environment clean and healthy, with a fresh addition of thiram to maintain a constant level of drug during the whole exposure period. All the experiment procedures, use of drug and the collection of samples were approved by the Institutional Review Board and the consent was granted by the animal ethics committee of The Islamia University of Bahawalpur for animal experimentation for the current study (IUB-1078/AS&R).

Estimation of median lethal concentration of thiram

After 15 days of acclimatization, the fish were weighed and equally distributed into different groups (n = 30 / group) and were given an increasing dose of thiram (0.55 mg/L, 0.60 mg/L, 0.70 mg/L, 0.75 mg/L, 0.80 mg/L) to determine the median lethal concentration (LC50). The mortality (%) of fish in response to various concentrations of thiram was used to determine the median lethal concentration of thiram for Labeo rohita at 96 h.

Experimental protocol

Subsequently, the fish (n = 96) were further distributed into four groups (24 / group) and different sub-lethal concentrations of thiram (Sigma Aldrich, USA) i.e. 40 μg/L, 80 μg/L and 120 μg/L were selected according to LC50 value of thiram for Labeo rohita, to avoid the mortality of fish due to toxicity of the drug. Group A was considered as control group, while the treatment groups B, C and D were given the dose of 40 μg/L, 80 μg/L and 120 μg/L, respectively. At different experimental days i.e. at 20 days, 40 days and at the end of the experiment (day-60), the fish were selected from each group (n = 8) for collection of blood and then slaughtered for collection of different organs like kidney, brain, heart and spleen for further analysis. For collection of blood, the fish was anesthetized with 0.3 ml/L (5–6 drops) of clove oil in water as described earlier42. A 22-gauge needle of 5 mL syringe was used for blood sampling and stored at 4°C in labeled EDTA tubes until further analysis.

Absolute and relative organ weights of fish

All the fish were weighed before the start and at every day of the experiment. Before dissection, each fish was weighed to determine the total body weight (gm) and absolute and relative weights (gm) of each collected organ (kidney, brain, heart, spleen) were determined at different concentrations of thiram, by using digital portable weighing balance (Shimadzu ELB3000) with an accuracy of 0.01 g.

Genotoxicity evaluation (Comet assay)

For DNA damage studies, the electrophoresis process was performed at alkaline conditions. Briefly, thin smears of 1% low melting and normal melting agarose were applied on forecasted glass slides having sample on it. After preparation, the slides were put in lysing (chilled buffer) solution and then placed in electrophoresis tank for 25–30 min at 25 V. Later on, the neutralization of slides was done with 0.4 M Tris buffer (pH 7.5). Finally, the slides were stained with ethidium bromide and observed under Oxion fluorescence microscope (Euromex Ox range, Netherlands) at 400X, as described earlier43.

Hemato-biochemical studies

For hematological parameters, erythrocyte count (106/mm3), total leukocytic count (103/mm3), lymphocytes (%), monocytes (%) and neutrophils (%) counts and hemoglobin (Hb) concentration (g/dl) were determined by automatic hematology analyzer (BK-5000VET, Biobase, Shandong, China), as previously described14,44. The collected serum was used to determine various biochemical parameters including alanine amino transferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphate (ALP), creatinine (Cr), urea and total proteins by using commercially available kits and Microlab 300 Biochemistry Analyzer (ELITech Group SAS, France), as described earlier45,46.

Tissue sampling for histo-pathological and enzymes studies

The fish was dissected carefully on days-20, 40 and 60 of the study by following the standard laboratory rules and the tissues samples of kidney, heart, brain and spleen of fish were collected. A part of tissue samples (0.5–1.0 cm) of collected organs were fixed in 10% formol solution and then processed by paraffin sectioning technique45,47,48 by using Tissue-Tek® VIPTM 5 Jr (Sakura Finetek, Japan). Histological slides having 4-5 μm thick tissue sections were prepared and then stained by Hematoxylin and Eosin technique by using Tissue-Tek® DRSTM 2000 Slide Stainer (Sakura Finetek, Japan), as previously described49,50,51.

For biochemical testing, 100 mg of each tissue was weighed and minced on ice cold petri plates and then homogenized in hand held homogenizer by adding 0.1 mg of phenylmethyl sulphonyl fluoride and 100 μL of lysis buffer. The lysate was then centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 15 min at room temperature by EBA 20 Centrifuge (Hettich North America, London, UK) and the supernatant was collected and stored at -20 °C, until further analysis. The tissue homogenates were analyzed for oxidative stress parameters and anti-oxidative enzymes activity in the treated fish compared to the control group.

Catalase (CAT) activity was measured using 50 mM of PBS (pH: 7) and 5.9 mM of H2O2, as described earlier52. The absorbance was measured at 240 nm under UV-visible spectrophotometer (Rx Monza UV Vis spectrophotometer, Randox Laboratories Ltd, UK). The catalase activity in erythrocytes lysate was determined by following the protocol of Aebi53. The activity is measured in units per milligrams of protein and is defined as 1 mmol of H2O2 degraded per minute. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) anti-oxidant was observed in the organ tissue samples54,55 and blood56, by previously described protocols. The absorbance was measured at 560 nm using UV-visible spectrophotometer and expressed as units/mg of sample of tissue or blood. To determine peroxidase (POD), the absorbance was observed at 470 nm using UV-visible spectrophotometer, as described earlier57 and was expressed as units/mg of protein. For determination of reduced glutathione (GSH), 5,5̍-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) DTNB or Ellman′s reagent (0.5 mL) along with disodium hydrogen phosphate buffer (1 mL) and homogenate tissue sample (0.1 mL) were used with slight modifications, according to the method described earlier58. The absorbance was measured at 412 nm both in tissue and blood samples. The level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was measured using 1:25 of reagent 1 (Nˈ N Diethyl Paraphenylenediamine) and reagent 2 (Ferrous sulfate stock solution), as described earlier59. The readings were taken at 505 nm and were expressed as units/mg of blood/ tissue homogenate sample. Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) was determined by previously described method60. Briefly, Tris-HCl (150 mM), ascorbic acid (1.5 mM), FeSO4 (1 mM) and 0.1 mL of tissue homogenate in a test tube, vortexed for 5 minutes and then incubated for 15 minutes. Then, 1 mL trichloroacetic acid (TCA 10%) and thiobarbituric acid (TBA 0.375%) were added, vortexed and boiled at 100 °C for 15 minutes in water bath. Then the mixture was centrifuged at 960 rpm for 10 minutes, the supernatant was collected and observed at 532 nm on a UV-visible spectrophotometer.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed with statistical software IBM SPSS (version 20) for windows 10 pro 64 bit operating system and were presented as mean±S.D. The statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Secondly, the generated data set were analyzed by performing principal component analysis (PCA) using GraphPad Prism 9.0. The difference were considered as statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Thiram is a widely used fungicide that has been reported to have detrimental effects on aquatic organisms24. Understanding the impacts of thiram exposure on various aspects of fish physiology is crucial for assessing its potential ecological risks. In this study, we investigated the effects of thiram on clinic and behavior changes, body weight, hemato-biochemical analysis, DNA damage, oxidative stress and anti-oxidant enzymes as well as histo-pathological alterations in the heart, brain, kidney and spleen of Labeo rohita were observed.

Determination of LC50 of thiram in Labeo rohita

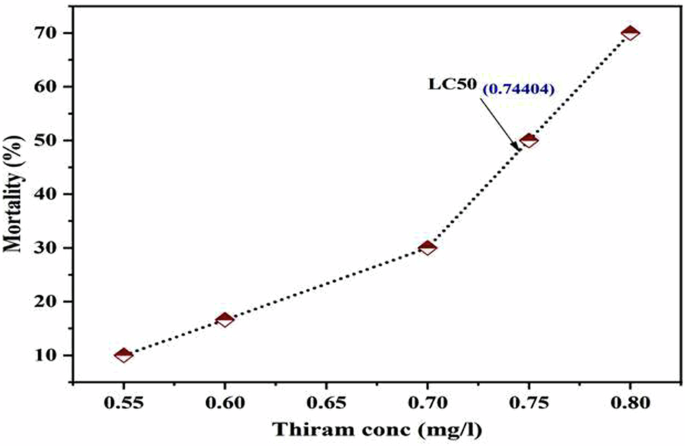

In the first experiment, the fish were exposed to different concentrations (0.55 mg/L, 0.60 mg/L, 0.70 mg/L, 0.75 mg/L, 0.80 mg/L) of thiram and the mortality of fish at each concentration was noted (Table 1). The mortality recorded throughout the experiment by these concentrations of thiram was observed in a dose-dependent manner and the probit analysis indicated the median lethal concentration (LC50) value for thiram in Labeo rohita as 0.744 mg/L (Fig. 1). To the best of our knowledge, we have estimated the median LC50 of thiram in Labeo rohita for the first time in the current study. Previously, LC50 of thiram in freshwater fish Cyprinus carpio and Rainbow Trout has been determined at 96 h as 0.66 mg/L61 and 0.10 mg/L62, respectively. Similarly, 96-hr LC50 value of different matels like cadmium has been determined in Labeo rohita as 24 mg/L63. Likewise, LC50 values for endosulfan and fenvalerate at 24 h were found to be 0.6876 µg/L and 0.4749 µg/L, respectively64. However, LC50 of this commonly used fungicide thiram has never been determined and the thus, has been reported for the first time in the current study.

The analysis revealed that 50% of fish were died at thiram concentration of 0.744 mg/L.

Behavioral clinical signs and mortality

Later on, different sub-lethal concentrations of thiram were tested for various patho-physiological effects of the drug in Labeo rohita. There observed no unusual adverse effects and the changes in the behavioral signs of the fish were observed in a dose-dependent manner. The swimming rate was increased in the groups treated with higher doses of thiram (80 μg/L and 120 μg/L) and the lesions were observed on the body surface especially near the gills. At few days after the start of the experiment, the fish of these treated groups lost their power of equilibrium and remained near to the surface of water. Moreover, mucus secretion was oozed out from the gills and mouth, there was bulging of eyes, loss of coordination in swimming, sudden erratic movements and air gulping were other clinical and behavioral changes that were more frequently observed in the groups treated with higher doses of thiram (80 μg/L and 120 μg/L). During the later days of the experiment i.e. at days-40 to 60, the fish of the group D (120 μg/L of thiram) were lying down at the bottom of the aquarium on one side and show erratic movements (Supplementary Table 1).

Body weight and organ weights

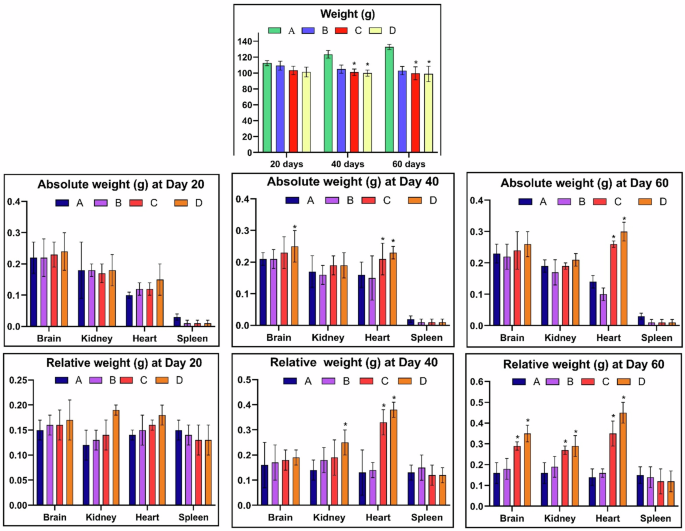

There observed a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in the body weight of the fish with an increase in the dose of thiram and increase in the time of exposure (Fig. 2). The fish in the control group A showed a usual growth pattern and thus, there observed an increase in the weight of fish with the passage of time. While, a relative decrease in the body weight was found in the group B treated with 40 μg/L of thiram at 40 days. Moreover, a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in the weight was recorded in the groups C (80 μg/L) and D (120 μg/L). The observed changes in the body weight of fish in thiram treated groups can be attributed to metabolic disturbances, decreased feed intake, altered food absorption or due to stress reactions65. These processes might result due to decreased appetite of the fish, altered metabolism, reduction in protein utilization and growth inhibition. Accordingly, toxic effects of pyriproxyfen lead to patho-physiological effects in Labeo rohita leading to decrease in body weight66 and even the toxicity effects cause reduced birth and body weight in humans67,68 and even reduce the plant weight and length69.

There observed a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in the body weight of fish, while the absolute (p < 0.05) and relative (p < 0.05) organ weights were significantly increased with an increase in the dose of thiram and time of exposure. A = Control group, (B) = 40 μg/L, (C) = 80 μg/L, (D) = 120 μg/L, * = p < 0.05.

On the other hand, thiram causes a significant increase in the organs weight in a dose and time dependent manner as likely acetochlor and pyriproxyfen caused an increase in the organs weight in Aristichthys nobilis70 and Labeo rohita71, respectively, however, there was no information available on the toxicity of thiram in L. rohita. The absolute (p < 0.05) and relative (p < 0.05) organ weights showed a significant increase in the weight of heart while only the relative weight of brain and kidney was significant (p < 0.05) increased with an increase in the time of exposure and dose of thiram. While no changes were observed in the weights of spleen of Labeo rohita (Fig. 2). The increase in weight of an organ might be attributed to treatment-related tissue alterations like hepatocellular72 and myocardial hypertrophy in rats73, tubular hypertrophy or chronic renal nephropathy74 and interstitial edema in testes of rodents75.

Hematological and serum biochemistry analysis

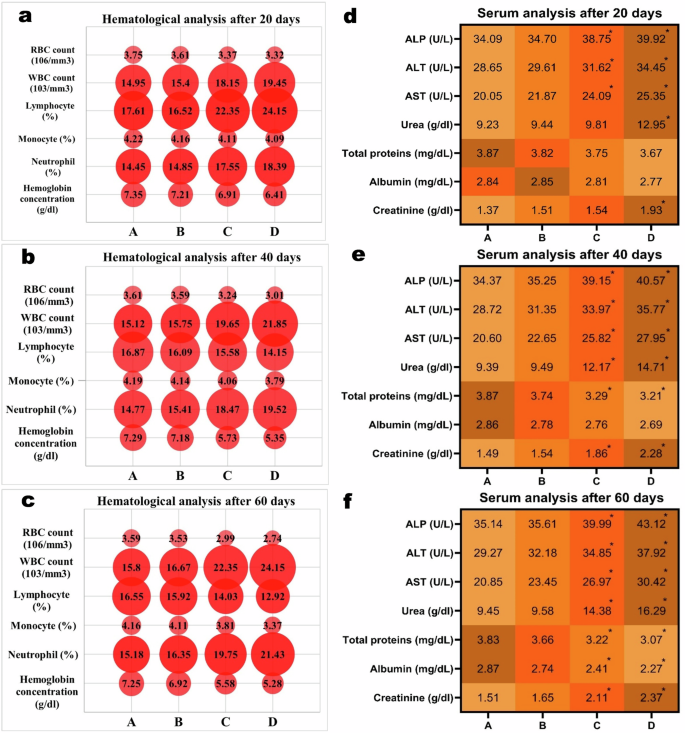

In aquatic and terrestrial organisms, hemato-biochemical indices are considered to be the best indicator and potential tool to assess the effects of different contaminants on health condition and physiological parameters of the fish76,77,78,79,80,81. In the current study, the values of RBCs, lymphocytes and monocytes percentages and Hb concentration were found to be decreased in the fish exposed to various concentrations of thiram. The fish exposed to higher doses of 80 μg/L and 120 μg/L showed a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in total erythrocyte count, percentage of monocytes and lymphocytes and total Hb concentration at days-40 (Fig. 3b) and 60 (Fig. 3c) of the experiment as compared to the control group. This decrease might be due to destruction and hemolysis of RBCs and therein an increased oxidation of hemoglobin82,83. Similar to these results, previously the toxic effects of pyrethroid permethrin and fungicide difenoconazole on hematological and anti-oxidant enzymes of Cyprinus carpio84 and L. rohita85 have been reported, respectively. Moreover, recently a significantly lower values of RBCs count and Hb concentration have been found in Albino rats due to toxic effects of thiram24. It might also be that these decreased hematological observations might be due to decreased production of hematopoietic tissues, enhanced production of free radicals and could also be due to insufficient supply of oxygen to the blood forming cells causing cell death. Contrarily, the higher doses of thiram showed a significant (p < 0.05) increase in the total leukocyte count and neutrophil percentage at days-40 and 60 of the trial (Fig. 3a-c) as like thiram was found to cause an increase in total leukocytic count and neutrophil percentage in male Albino rats24. Similarly, severe hematological alterations have also been observed in Freshwater Catfish Mystus keletius, Chameleon cichlid Australoheros facetus and Oreochromis niloticus due to pesticides Ekalux (EC-25%) and Impala (EC-55%)86, fungicide azoxystrobin87 and mancozeb88, respectively.

An increase in the dose of thiram and time of exposure lead to a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in RBCs count, monocytes, lymphocytes, Hb concentration (a–c) and total proteins, while total WBCs, urea, creatinine and liver enzymes were significantly (p < 0.05) increased (d–f). A = Control group, B = 40 μg/L, C = 80 μg/L, D = 120 μg/L, *p < 0.05.

It is observed that the evaluation of different serum biochemical parameters provide a legitimate data for demonstration of patho-physiological status and toxicological screening of different environmental pollutants in different aquatic and terrestrial animals. Among the serum biochemical parameters, the level of albumin and total proteins were showed a significant decrease at days-40 (p < 0.05) and 60 (p < 0.05) in the group of fish exposed to 80 μg/L and 120 μg/L of thiram (Fig. 3d–f). Whereas, the values of urea, creatinine, alkaline phosphate, aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase showed a significant (p < 0.05) increase in the fish exposed to higher concentrations (80 μg/L and 120 μg/L) of thiram at days-40 and 60 of the experiment (Fig. 3d–f). The significantly increased concentration of hepatic enzymes in our study is due to toxic effects of thiram that play the key roles in carbohydrates and protein metabolism. The fungicides like folpet and propiconazole have been found to cause an increase in the quantity of liver enzymes in common carp Cyprinus carpio89 and Sprague-Dawley rats90, respectively. Moreover, the elevated values of urea and creatinine might be attributed to altered filtration mechanism of kidneys, as also previously observed in bisphenol17 and pymetrozine91 induced toxicity in bighead carp Aristichthys nobilis. While a significant decrease in the total proteins in our study could be due to malabsorption of the insufficiently in-taken protein contents92, as observed in grass carp Ctenopharyngodon idella due to toxic effects of herbicides atrazine93 and an insecticide profenofos94.

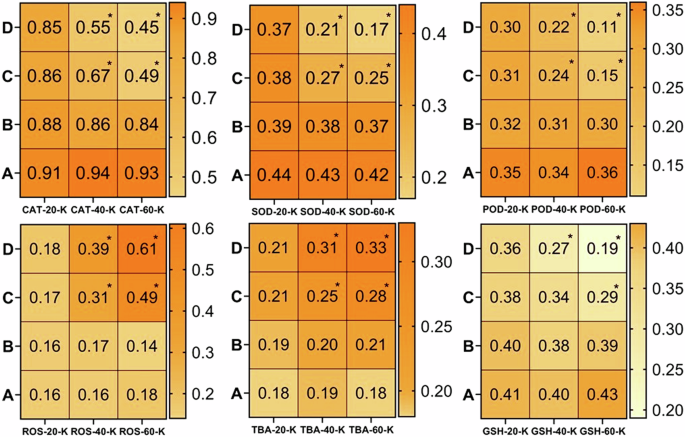

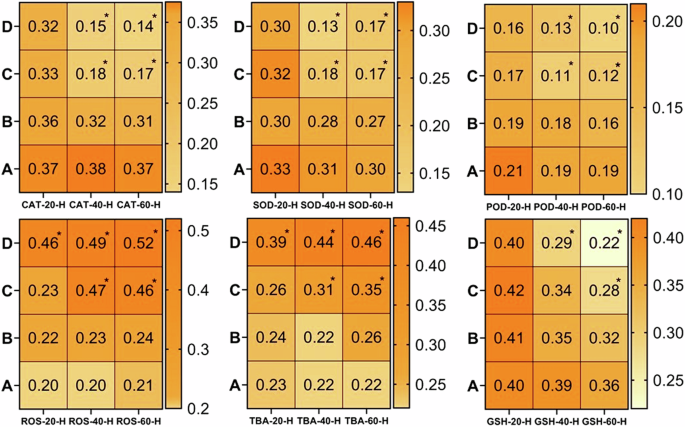

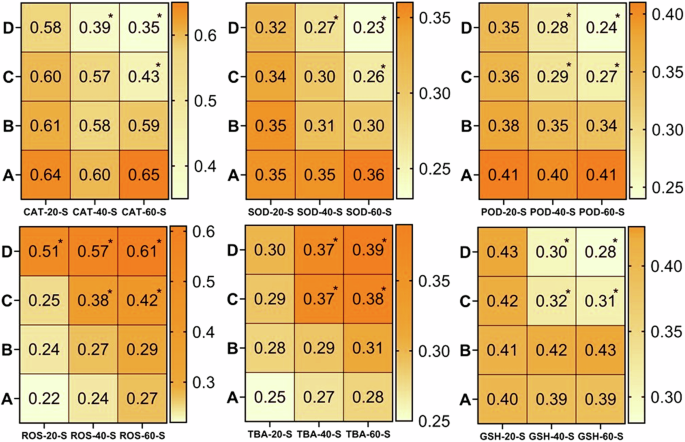

Oxidative stress parameters and anti-oxidant enzymes

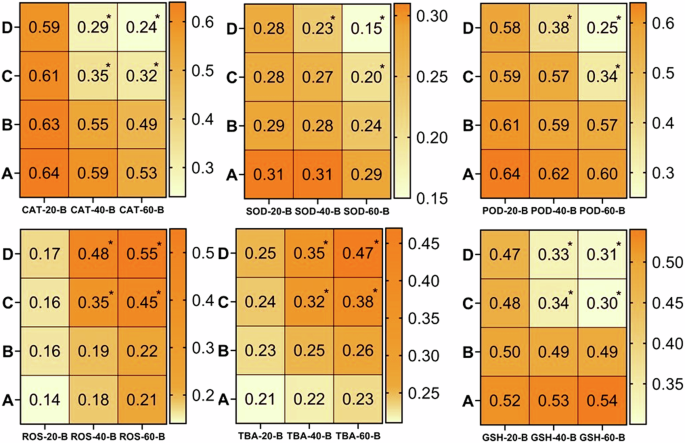

It is quite well-known that estimation of oxidative stress parameters (ROS, TBARS) is the best indicator of inflammatory response and the anti-oxidative enzymes (CAT, SOD and GSH) are effective tools for protecting the tissues from free radical-induced damage95,96. The results of the current study revealed a significantly (p < 0.05) higher production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and TBARS in the homogenate tissue samples of brain (Fig. 4), kidney (Fig. 5), heart (Fig. 6) and spleen (Fig. 7) collected at days-40 and 60 in the groups C and D treated with 80 μg/L and 120 μg/L of thiram as compared to group A. The values were increased with an increase in the dose of thiram and with the increase in the time of exposure and the highest values were recorded in the group D treated with 120 μg/L of thiram at the day-60 of the experiment. While the values of CAT, SOD, POD and GSH contents were significantly (p < 0.05) decreased in the groups C and D as compared to control group A. In principal components analysis (PCA), it was found that first 3 principal components described by 100% total variation and eigenvalues along with their PC scores in the fish exposed to thiram were significantly (p < 0.05) altered in the homogenate samples of brain (Supplementary Fig. 1), kidneys (Supplementary Fig. 2), heart (Supplementary Fig. 3) and spleen (Supplementary Fig. 4) tissues. The proportion of variance, eigenvalue, biplots and loading results in the respective tissues of L. rohita showed a significant (p < 0.05) increase with an increase in the concentration of the dose of thiram and exposure days in the fish of the treated groups as compared to the control (Supplementary Figs. 1–4).

There observed a significantly (p < 0.05) increase in ROS and TBARS while a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in anti-oxidative enzymes was found at days-40 and 60 in the fish treated with 80 μg/L and 120 μg/L of thiram. A = Control group, (B) = 40 μg/L, (C) = 80 μg/L, (D) = 120 μg/L, * = p < 0.05.

There found a significant (p < 0.05) increase in the level of ROS and TBARS and while a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in anti-oxidative enzymes with increase in the dose of thiram at days-40 and 60. A = Control group, (B) = 40 μg/L, (C) = 80 μg/L, (D) = 120 μg/L, * = p < 0.05.

There observed a significantly (p < 0.05) increase in ROS and TBARS while the anti-oxidative enzymes were significantly (p < 0.05) decreased with increase in the dose of thiram at days-40 and 60. A = Control group, (B) = 40 μg/L, (C) = 80 μg/L, (D) = 120 μg/L, * = p < 0.05.

A significant (p < 0.05) increase in the values of ROS and TBARS was observed while the anti-oxidative enzymes were significantly (p < 0.05) decreased with increase in the dose of thiram at days-40 and 60. A = Control group, (B) = 40 μg/L, (C) = 80 μg/L, (D) = 120 μg/L, * = p < 0.05.

It is well known that oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species and the anti-oxidant defense mechanisms of the organism97. ROS are highly reactive molecules that cause damage to the cellular components including proteins, lipids and DNA42. To counteract the harmful effects of ROS, organisms have an anti-oxidant defense system that includes various enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx)98. In has been reported that when fish are exposed to fungicides, it leads to increased generation of ROS within the body tissues99 and the excessive production of ROS devastates the anti-oxidant defense mechanisms resulting in oxidative damage79. The continuous generation of ROS surpasses the capacity of anti-oxidant defense system causing the enzymes to become overwhelmed and depleted100. Moreover, the fungicides also inhibit the activity of anti-oxidant enzymes, thus further contributing to their decreased status, as like azoxystrobin caused an inhibition of these enzymes in cichlid Australoheros facetus87 and zebrafish Danio rerio101.

In the same context as like we found in our study, it has been observed that the eco-toxicological effects of pesticides (ekalux; EC-25%, impala; EC-55%), fungicides (mancozeb) and herbicides (pendimethalin) lead to oxidative stress in the fish and a decrease in the anti-oxidant enzymes in freshwater catfish Mystus keletius102, Oreochromis niloticus88 and bighead carp Hypophthalmichthys nobilis103, respectively. In the current work, the decreased anti-oxidant enzymes in the fish exposed to different doses of thiram has several implications. Firstly, it signifies a compromised ability of the fish to neutralize and eliminate ROS, leading to higher oxidative damage to the cellular components. This oxidative damage could affect various physiological processes and contribute to the development of oxidative stress-related diseases like myocardial infarction and stroke104. Furthermore, the decrease in antioxidant enzymes disrupts the redox balance within the fish tissues and further exacerbating the oxidative stress damage15. This imbalance leads to a cascade of detrimental effects including tissue damage, organ dysfunction and impaired cellular processes42.

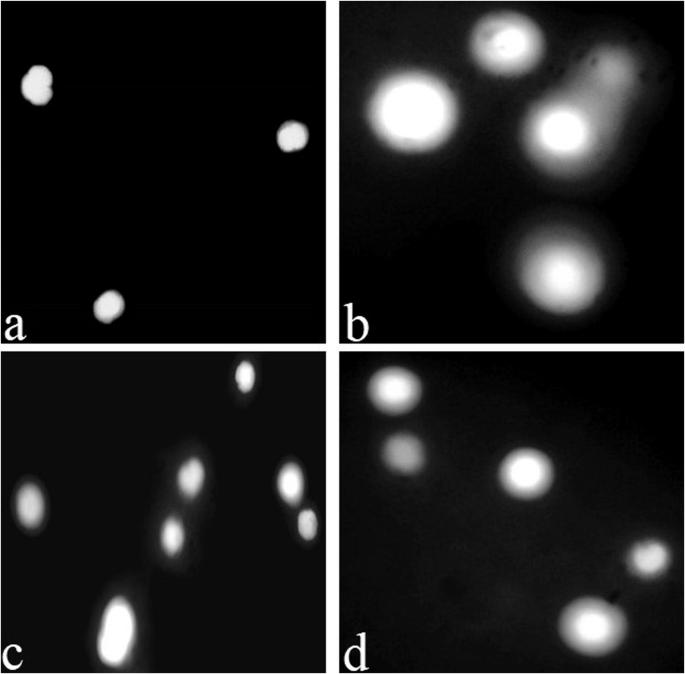

Genotoxic potential by DNA damage studies

In the present study, comet assay under alkaline conditions showed a significantly increased percentile rate of DNA damage in the heart, kidneys and brain (Fig. 8). It has been declared that the comet test is a sensitive, appropriate and frequently used approach for assessing the DNA damage in various tissues of Labeo rohita70,105 and Hypophthalmichthy snobilis106. At day-20, no DNA damage was observed in any of the visceral organs of the fish in different treated groups (40 μg/L, 80 μg/L, 120 μg/L). However, the damage rate in the genetic material was increased with an increase in the dose of thiram and the duration of the experiment in the isolated cells of brain (Supplementary Fig. 5), kidneys (Supplementary Fig. 6) and heart (Supplementary Fig. 7), that has also been further demonstrated with an increase in the percentile rate of DNA damage in the isolated cells of these different tissues (Supplementary Table 2). The damage was depicted with an increase in the size of the fluorescent area around the nucleus due to DNA fragments. There observed a severe damage in the DNA of renal epithelial cells (Fig. 8b) followed by cardiac myocytes (Fig. 8d) and neuronal cells (Fig. 8c) at the end of the experiment i.e. at day-60 compared to the non-treated (Fig. 8a) tissue samples. Similar to our study, different antimicrobial agents like chloroxylenol, borax, triclosan and methyl isothiazolinone have been reported to cause DNA damage in the blood cells of red tilapia Oreochromis sp.15, Labeo rohita66, rainbow trout107 and Oreochromis niloticus100 and thus, our study is the first report on DNA damage due to exposure of thiram in various histological tissues of L. rohita.

The severe DNA damage was observed in the renal tissue (b) followed by cardiac (d) and brain (c) tissues compared to the non-treated (a) tissue samples. The presence and caliber of fluorescent area around the nucleus having DNA fragmentation depicts the intensity of DNA damage.

Fungicides exert neurotoxic effects on brain and disrupt neuronal signaling, interfere with neurotransmitter release and uptake and impair synaptic transmission108. This disruption in normal neuronal function leads to altered behavior, impaired cognition and compromised neurological development. Moreover, these fungicides imidacloprid and clothianidin were found to induce oxidative stress in the nervous tissue of L. rohita109. It has now becomes quite obvious that the pesticides cause DNA damage in different body tissues and the blood cells that could be due to key markers of oxidative stress (ROS and TBARS). The generation of ROS might surpass the anti-oxidant defense mechanism in the brain, leading to oxidative damage to cellular components and thus, disrupts the normal brain function and contributes to neuro-degenerative processes110. Moreover, exposure to fungicides also triggers the inflammatory responses, cause activation of immune cells and release of inflammatory mediators that leads to neuro-inflammation which further contributes to neuronal damage and dysfunction111. They can also disrupt the synthesis, release or re-uptake of neurotransmitters, leading to altered neurotransmitter levels and impaired neuronal communication112.

Histo-pathological observations

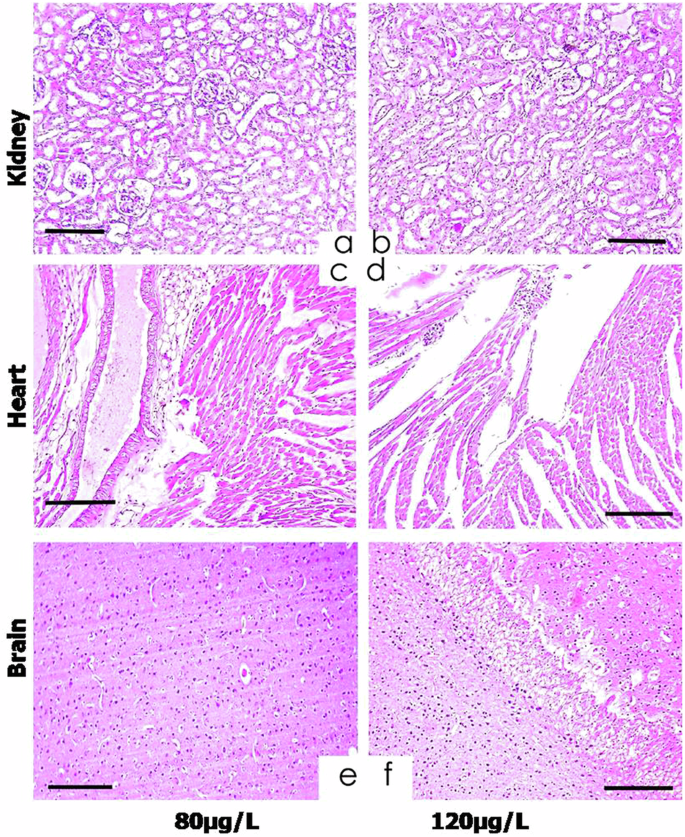

The significant histo-pathological alterations in various organ tissues of fish act as important markers for toxicological studies especially pesticides toxicity81,113. The histo-pathological alterations in the tissues were mild at the start of the experiment, in the organs of fish treated with low dose (40 μg/L) of thiram, were moderate with high dose (80 μg/L) and became severe with highest dose (120 μg/L) of the drug up-to the end of the experiment (Fig. 9). At day-60, the histo-pathological lesions in the kidneys of fish treated with thiram were found to be necrosis of cuboidal or columnar epithelium of renal collecting ducts, presence of inflammatory exudates in the interstitial space, degeneration of renal tubules, infiltration of melano-macrophages, irregular renal corpuscle, cellular degradation of tissues, vacuolation, acute cellular swelling, increased urinary space in the Bowman’s capsule and detachment of cells from the basement membrane were observed (Fig. 9a, b). Different microscopic alterations in the heart of fish treated with higher doses of thiram exhibited fatty infiltration, necrosis and degeneration of heart muscular tissues, cardiac myocyte dystrophy and disorganization. These changes were more clearly shown in the groups treated with higher doses (80 μg/L and 120 μg/L) of thiram at the days-40 and 60 of the treatment (Fig. 9c, d). Various histo-pathological changes in the brain tissue includes necrosis of neuroglial cells, atrophy of neurons, structural degeneration of cerebral cortical pyramidal cells and microgliosis in the fish at 40 days of exposure observed in the groups C and D as compared to control group (Fig. 9e, f). Moreover, a large number of hypertrophic splenocytes was observed in the histo-pathological sections of spleen of fish exposed to various doses of thiram. It has also been previously observed that exposure to insecticide triflumezopyrim causes histo-pathological alterations like cellular degeneration, neuronal loss, vacuolation and disruption of normal tissue architecture in the brain tissue of L. rohita114. The specific effects of fungicides on nervous tissue depend on various factors including concentration of the drug and duration of exposure, individual susceptibility and the mode of action of the pesticide or fungicide used115.

The histo-pathological lesions in the kidneys were found to be epithelial necrosis of collecting ducts, presence of inflammatory exudates in the interstitial space, degeneration of renal tubules, irregular renal corpuscle, vacuolation, acute cellular swelling and increased urinary space (a, b). Different microscopic alterations observed in the heart were fatty infiltration, necrosis and degeneration of muscular tissues, myocyte dystrophy and disorganization (c, d). Various histo-pathological changes in the brain tissue included necrosis of neuroglial cells, atrophy of neurons and microgliosis (e, f). Hematoxylin and eosin staining, scale bar = 100 μm.

Lipid peroxidation, a consequence of oxidative stress can lead to degradation of cell membrane lipids in the organ tissues and produces reactive aldehydes that can further damage to cellular components and disrupt the membrane integrity116. These alterations in the cell membrane affect the proper functioning of ion channels and transporters that are essential for maintaining the normal cardiac electrical conductivity117. Similarly, kidneys are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress due to their high metabolic activity, extensive involvement in the filtration and excretory processes and exposure to a variety of xenobiotics118,119. To counteract the detrimental effects of ROS, the kidneys possess an anti-oxidant defense system that includes various enzymes (SOD, CAT, GPx) that play crucial roles in ROS scavenging and protection against oxidative damage120,121. SOD is among the key anti-oxidant enzymes in L. rohita involved in renal response to fungicide induced oxidative stress and is responsible for converting superoxide anions (O2-) into less harmful hydrogen peroxides (H2O2)122,123. Catalase (CAT) plays a vital role in further detoxification of H2O2 and prevents their accumulation124. Glutathione peroxidase is an important component of the cellular defense against oxidative stress and utilizes the anti-oxidant molecule glutathione (GSH) to convert H2O2 and organic hydroperoxides into water and corresponding alcohols103. However, the activity and expression levels of these anti-oxidant enzymes could be altered by fungicide exposure. Prolonged or high-level dietary exposure to methionine disrupted the balance between ROS production and the activity of antioxidant defense mechanisms, leading to oxidative damage and a decrease in the activity of antioxidant enzymes in L. rohita125. Moreover, the decrease in the enzyme activity further exacerbated the oxidative stress in the tissues and thus, the impaired antioxidant enzyme activity in the fish exposed to a fungicide results in the accumulation of ROS, oxidative damage to diverse cellular components, inflammation and impairment of kidney function. These effects then ultimately lead to renal dysfunction, impaired excretion processes and an increased susceptibility to several secondary infections or environmental stressors126. The observed decreased activity of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT and GSH) indicates a compromised ability to neutralize and eliminate ROS and hence, the oxidative damage occurred within spleen or other tissues potentially affect the immune function and overall the health of the fish127. Similar to our findings, ROS and H2O2 levels have been found to increase in the rats exposed to glyphosate toxicant128. It is important to note that ROS production is largely affected by toxicant concentrations, cellular backgrounds and the duration of exposure129,130. The results of the current study demonstrated that thiram cause DNA damage in the organs like brain, kidney, heart and spleen of L. rohita by elevating the reactive oxygen species and lowering the levels of antioxidant enzymes.

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first comprehensive report of the toxic effects of thiram on stress and anti-stress profiles in different organs of L. rohita. It is quite obvious that understanding the effects of a drug is essential to assess the potential risk factors and the possible ecological consequences and thus, it is hereby utmost required for extensive investigations to explore the underlying mechanisms and to identify the specific gene mutations / alterations through molecular studies to identify the long-term effects of this drug in order to mitigate the toxic effects and to ensure the health and well-being of the aquatic ecosystems.

It has been found that thiram causes severe toxicity in L. rohita, it reduces the body weight of the organism but significantly increased the absolute and relative weights of heart, brain, kidney and spleen. There observed an increase in the ROS and TBARS production and a decrease in antioxidant enzymes status like CAT, SOD, POD and GSH. The results were further confirmed by comet assay and histo-pathological observations that clearly demonstrated the harmful effects of thiram in different organ tissues of the selected fish. The alterations in hemato-biochemical parameters and histopathology of various organ tissues of fish demonstrated as imperative biomarkers to monitor the aquatic contamination of fresh and surface waters due to pesticide addition. It has thus been concluded that this extensively used fungicide thiram upon penetrating the water bodies severely pollute the marine environment and the aquatic eco-system, become hazardous for aquatic species by causing severe health effects for water creatures specifically fish and thus, rendering the apparently clean water to be unfit for human consumption by entering in to the food chain.

Responses