Selectivity and morphological engineering of a unique gallium−organic framework for antibiotics exclusion in water

Introduction

A large amount of research performed in the recent past shows that many types of drugs (antibiotics, pain relievers, etc.) and personal care products have emerged as a major source of organic micropollutants in the aquatic environment1,2. Pharmaceutical antibiotics are essential for improving human and animal health, particularly by combating bacterial infections. They are widely used in medicine and aquaculture but have also contributed to the development of antimicrobial resistance3,4. Noteworthy, among all the antibiotics, the aminoglycosides (AGCs) class is the most widely used veterinary medicine in all food-producing animals to treat bacterial infections5. The World Health Organisation classifies these antibiotics as a critically essential human medicine. Amikacin (AMC)6, Kanamycin (KMC)7, and Tobramycin (TMC)8 antibiotics are effective against rapidly growing bacteria. They are highly used in humans and veterinarians to treat infections caused by gram-positive and negative bacteria. These antibiotics are most widely used to treat pneumonia, urinary tract infections, soft tissue infections, mastitis, sepsis, and other infections5. These antibiotics’ dosages are associated with severe side effects such as loss of hearing, toxicity to the kidney, respiratory failure, allergic reaction, and antibacterial resistance (ABR)9. The excess amount of antibiotics that enter the food chain or are excreted through urine, contaminate the environment causing a significant threat to human health and environmental safety worldwide10. Therefore, it is essential to trace antibiotic residue in food samples for the future well-being of humans and animals. Their continuous presence in water sources may increase microorganisms’ resistance, requiring higher concentrations to inactivate them in humans and animals11. Additionally, they have undesirable effects on healthy humans if they are ingested through water. Techniques such as Fenton biological degradation12, adsorption13, nano-filtration14 via the membrane15, ozonation16, etc. can be used to remove these antibiotics from water sources17.

However, monitoring antibiotics in wastewater before applying advanced removal technologies, and identifying any remaining antibiotic residues post-purification, is a key challenge in tackling antibiotic pollution. Although various analytical and chemical methods are known for the elimination of antibiotics, it seems that the existing methods are too expensive. Therefore, it is much more practical to develop suitable methods for the rapid and effective removal of antibiotics in aquatic systems18. Among them, adsorption is considered to be an excellent method for treating wastewater containing low concentrations of antibiotics because of its high efficiency and antitoxic nature19,20. Over the past few years, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have attracted extensive attention from researchers due to their properties such as greater adsorption sites21, surface area22, excellent recyclability23, pore volume24, easy modification25, low density26, easy tenability of pore shape and size27, and unique structural characteristics make them materials of special interest especially in the field of adsorption28. MOFs are materials composed of organic linkers and inorganic blocks that are tightly bonded together through a process known as reticular synthesis. This bonding results in a textured structure characterized by permanent porosity. In this context, MOFs have recently been advanced as viable platforms for the removal and detection of trace amounts of pollutants in water. However, MOFs, have demonstrated their rapid, convenient, and detectable ability to remove dyes, organic pollutants, drugs, and heavy metal ions. Also, MOFs materials have been used as effective chemical sensors. In this work, we utilized a unique Gallium-Organic Framework (Ga-MOF). Experimental findings show that Ga-MOF exhibits excellent stability in various solvents and across a range of pH levels, making it an effective sensor for detecting antibiotics like amikacin29. Moreover, Ga-MOF exhibits strong anti-interference capabilities, setting it apart from similar antibiotics by remaining unaffected by various interfering ions. Additionally, Ga-MOF has demonstrated reliable reusability in amikacin detection, maintaining both stability and effectiveness over five consecutive cycles29. Notably, Ga-MOF combines a high surface area, exceptional stability, and a well-defined porous structure, making it a highly effective adsorbent. Their unique gallium coordination sites enable selective interactions with target molecules, while customizable organic linkers allow fine-tuning of pore size and surface chemistry. This adaptability enhances their ability to adsorb specific compounds through interactions like hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking, making Ga-MOFs versatile for a range of environmental and industrial applications. The stability of MOFs in aqueous environments is significantly influenced by their chemical structure, particularly through modifications such as imine functionalization. When comparing the stability of imine-modified frameworks (F-MOF) to their original counterparts (Ga-MOF), several factors come into play. Imine modifications can enhance these bonds, potentially increasing the framework’s resistance to hydrolysis and degradation in water30,31. The introduction of hydrophobic groups through imine modification can help repel water molecules, thereby reducing their interaction with the MOF structure. This can lead to improved kinetic stability, as less water penetration means a lower likelihood of bond breakage and structural collapse30,32. The coordination environment around metal ions is crucial for stability. Modifications that alter this geometry can either enhance or detract from the MOF’s stability in aqueous conditions. For instance, imine ligands may provide a more rigid structure that better withstands external stressors31,33. Strong coordination bonds formed through imine modifications can increase the thermodynamic stability of the MOF, making it energetically unfavorable for water to disrupt these bonds. This is particularly important in maintaining structural integrity during prolonged exposure to water30,32. The ability of a modified MOF to retain its crystallinity and porosity in aqueous conditions is crucial for its application in water remediation. Imine modifications may enhance these characteristics by stabilizing the framework against hydrolytic degradation30,34. It is worth noting that until now only a few studies have been conducted to detect and remove antibiotic pollutants from wastewater using MOFs materials and their adsorption mechanism. For instance, Xie et al.29 synthesized a modern gallium−organic framework for amikacin detection in a Serum. Their experimental analysis reveals that this MOFs can be used as a stable, fast, and recyclable luminescent probe for the detection of amikacin in aqueous solution and serum. Besides, Akhzari et al.35 investigated the 2D organic frameworks for the removal of pharmaceuticals in aquatic ecosystems. They found that the organic frameworks were a promising adsorbent for excluding pharmaceutical pollutants. Their results showed that the hydrogen bond and X–H⋯π (X=N, O, C; π=π electrons) play a crucial role in removing pollutants. Besides, Soltanieh et al.36 developed a silver-decorated MOF through an in-situ copolymerization method for neomycin antibiotic removal from an aqueous solution. Their analysis illustrated the exothermic and spontaneous nature of neomycin adsorption onto the synthesized composite. Northworthy, computational simulations provide essential insights into the mechanisms of pollutant adsorption. Techniques such as molecular dynamics (MD) and metadynamics serve as powerful tools for modeling the interactions between contaminants and adsorbents within a controlled virtual environment. These methods offer detailed information that is often difficult to obtain through experimental approaches. By enabling precise atomic-level modeling, these simulations are particularly advantageous for applications in water treatment. In the current study, the adsorption affinity of a three-dimensional gallium-organic framework (Ga-MOF) for the removal of three pharmaceutical contaminants (AMC, KMC, and TMC) from aquatic ecosystems was investigated using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations combined with well-tempered metadynamics. This computational approach provides a detailed analysis of how effectively the Ga-MOFs can adsorb these pollutants, offering insights into its potential application in water purification. Furthermore, we assessed how functional imide groups facilitate antimicrobial contaminant adsorption on the Ga-MOFs surfaces. Our analysis focused on examining the free energy surface (FES) of the pollutant’s adsorption process on MOFs and its functionalized form (F-MOFs) surfaces through an examination of well-tempered metadynamics. Our objective was to determine whether the functionalization of the substrate with imide groups can increase the adsorption efficiency of the substrate or whether the other functional groups should be considered. Meanwhile, the role of hydrogen bonds and vdW interactions in the adsorption of pollutants on the substrate’s surface will also be investigated. This work aims to highlight the further research of modified frameworks in the field of antibiotic-polluted water treatment and to give direct attention to the future research of MOFs materials in the antibiotic-polluted water industry.

Methods

Molecule dynamic simulation

The potential of Ga-MOF as viable options for the removal of AMC, TMC, and KMC from wastewater was investigated using a molecular dynamics simulation.

MD simulations have been performed to investigate the stability and properties of MOFs substrate to capture KMC, AMC, and TMC antibiotic contaminants in water. Notably, the first MOFs crystal structure is derived from X-ray data published in the study of Xie et al.29. A conjugated 4,4′,4″,4″′-(1-4-phenlene-bis(pyridine-4,2,6-triyl)) (H4PPTA) ligand is chosen as the monomer to construct a unique three-dimensional Ga-MOF. To modify the MOF materials, four imide groups were used in four different positions, creating the MOFs-imide (F-MOFs) structure see Fig. 1. Generally, imine modification of Ga-MOFs to form F-MOFs can enhance stability in aqueous environments through increased hydrophobicity, stronger coordination bonds, and improved structural integrity. These modifications are essential for ensuring that the MOFs perform reliably in practical applications such as water remediation, where exposure to moisture is inevitable. The overall effect is a framework that not only resists degradation but also retains its functional capabilities over time. In this work, six simulation boxes are designed, each containing six antibiotic molecules, such as KMC, AMC, and TMC, (see Fig. 1) placed on top of MOFs/F-MOFs structure. GROMACS software package (version 2019.2)37 exclusively facilitated all MD simulations. The force field parameters for the F-MOFs/MOFs materials and antibiotic molecules, KMC, AMC, and TMC molecules are taken from the CHARMM3638, and the force field parameter of gallium is taken from the Wonglakhon et al.39 quantum mechanical calculations were performed at M06-2X/6-31G** level40 using Gaussian0941 to obtain the partial charge of MOF atoms. MOFs substrate consists of 256 oxygen atoms, 1408 carbon atoms, 728 hydrogen atoms, and 64 nitrogen atoms. The simulated boxes measure 12 × 12 × 12 nm³ and contain six antibiotic molecules along with MOFs at the center. A neutral environment is simulated using the 12153 TIP3P water model to assess the system. To maintain the separation of the system’s components from nearby cells, periodic boundary conditions42 are used. The non-bonded electrostatic and Lennard-Jones interactions are managed using the particle mesh Ewald technique, with a cutoff threshold of 1.4 nm. Using a threshold of 1.4 nm, the particle mesh Ewald approach is utilized to manage non-bonded electrostatic and Lennard-Jones interactions. The Nose–Hoover thermostat and the Parrinello–Rahman barostat help maintain the temperature and pressure at 310 K and 1 bar, respectively. The bond lengths are maintained at their equilibrium state by using a linear constraint-solving technique43. The simulated system is first relaxed by applying the steepest descent methods to minimize unwanted interactions44. Afterward, 1.5 fs time steps were used to run molecular dynamics simulations for 100 ns. The systems that are being studied have their initial settings displayed in Fig. 2. The Visual Molecular Dynamics45 tool is used to visualize the final results of the simulation.

An initial snapshot of the systems under investigation. The structure of (a) MOF and (b) F-MOF with (c) the monomer of MOF materials (H PPTA); color codes: O: red, N: blue, C: cyan, H: white, and Ga: pink.

a AMC, b: TMC, and (c): KMC.

Metadynamics simulations

With respect to the collective variables (CVs)45, the Parrinello et al.46 well-tempered metadynamics simulation method was used to find the FES. The metadynamics simulations utilize the PLUMED plug-in, version 2.5.247, which is included in the GROMACS 2019.04 package.

The well-tempered metadynamics approach uses a width of 0.25 Å and an initial Gaussian height of 1.0 kJ mol–1. 500 steps are employed for deposition, with a bias factor of 15. It is significant to remember that all systems under investigation have 100 ns of metadynamics simulation running. Overall, the free energy landscape for the adsorption of antibiotic molecules on the MOFs substrate is effectively approximated through the metadynamics simulations reported in this work.

MD simulation

Result and discussion

We investigated molecular dynamics simulations to explore the capability of MOFs substrates in adsorbing antibiotic drugs such as AMC, KMC, and TMC. Additionally, we investigated the influence of functionalization of MOFs substrate on the adsorption process of mentioned antibiotics by performing MD simulations. The analysis of MD simulation can give detailed insight into various aspects of interacting molecules, such as the energy interactions, the mechanism of spontaneous adsorption, the distribution of KMC, AMC, TMC molecules around the substrate materials, and the stability of six systems (refer to Table 1): KMC/MOFs, AMC/MOFs, and TMC/MOFs, also, KMC/F-MOFs, AMC/F-MOFs, and TMC/F-MOFs. The initial snapshots of the studied systems are provided in Fig. 2. Before running the designed simulation systems, energy minimization is performed on each of the systems. In each of the simulation systems, the MOFs or F-MOFs adsorbent is carefully placed in the center of the box simulation. After that, the antibiotic molecules are randomly positioned at ~2 nm from the substrate. The snapshots of the simulation process for the removal of the contaminants with the MOFs/F-MOFs substrate at the end of the simulation time are depicted in Fig. 3. As the simulation progresses, it is found that the distance between the pollutants molecules and substrate gradually decreases, leading to spontaneous adsorption. Upon closer examination of the corresponding snapshots (refer to Fig. 2), it can be observed that the number of adsorbed contaminants in the examined systems differs depending on whether they are on the outside of the MOFs/F-MOFs surface or within the interior cavity. The obtained results demonstrated that in the KMC/MOFs system, more of the molecules are adsorbed on the active sites of the substrate surfaces. Additionally, in the AMC/MOFs and the TMC/MOFs systems, most of contaminant molecules are adsorbed on MOFs substrate through π–π stacking and hydrogen bond interactions. These observations emphasize that the tendency of antibiotic molecules for adsorption on the active sites of the MOFs substrates is different, in such a way the KMC molecule shows the most affinity, whereas, the TMC has the less tendency for adsorption on examined substrates. Remarkably, the π electrons on KMC, AMC, and TMC molecules can create strong π–π stacking interactions with the MOFs surface. The analysis of molecular interactions suggests that the adsorption behavior and total energy of the process can be influenced by functionalizing the substrate with an imide group.

a KMC/MOFs, b AMC/MOFs, c TMC/MOFs, d KMC/F-MOFs, e AMC/F-MOFs, and (f) TMC/F-MOFs.

Our results show that upon functionalization of MOFs with the imide group, the tendency of KMC for adsorption on the substrate surface somewhat decreases. Whereas, with the functionalization of the substrate, the tendency of two other drugs for adsorption on the F-MOFs surface considerably increases, which can be due to the formation of more hydrogen bonds. It is worth mentioning that upon functionalization of MOFs, the KMC and AMC molecules have more tendency to adsorb into the pores of the F-MOFs substrate.

Root mean square deviation

All of the examined systems achieved equilibrium in roughly 3 ns, according to the root mean square deviation (RMSD) graphs (see Fig. 4). The RMSD curves of all systems show little geometric changes, as seen in Fig. 4, and the substrate morphology was constant for the duration of the simulation in all systems. Notably, the antibiotic molecules traverse a brief distance of 0.2 nm to access a substrate with a substantial contact surface area, where they ultimately adsorb. This characteristic bolsters stability and mitigates the pace of contaminants in aquatic environments. Consequently, it is reasonable to anticipate that these 3D frameworks serve as effective agents for antibiotic removal. Wang et al.48 synthesized two stable isostructural Zr(IV)-based MOFs, specifically Zr6O4(OH)8(H2O)4(TTNA)8/3 (BUT-13), aimed at removing antibiotics and organic explosives from water. Their research demonstrated that these MOFs exhibit excellent fluorescent properties, which can be effectively quenched by trace amounts of the antibiotics nitrofurazone (NZF) and nitrofurantoin (NFT), as well as the organic explosives 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (TNP) and 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) in aqueous solutions. Additionally, both MOFs displayed high adsorption capacities for these organic contaminants, highlighting their potential for simultaneous detection and removal of specific pollutants from water sources.

Root mean square deviation for the studied systems.

Interaction energies

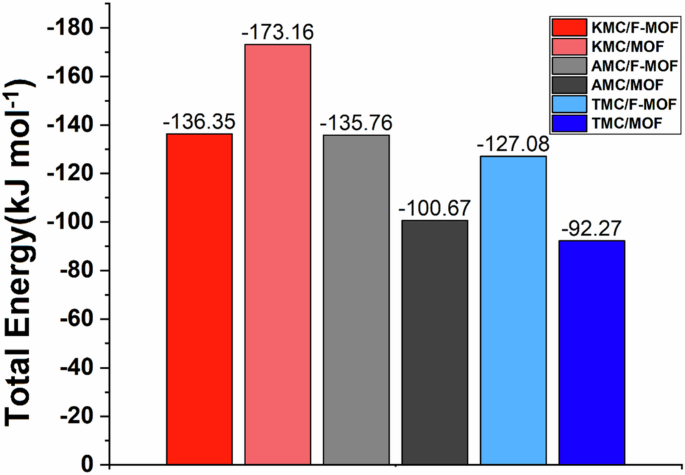

The interaction energies are investigated to be extended our understanding of the adsorption mechanism of KMC, AMC, and TMC molecules toward the MOF/F-MOFs substrate. Table 1 displays the average of electrostatic (elec) and van der Waals (vdW) energy values. The negative values in the table indicate that the adsorption process of drugs on MOFs and F-MOFs occurs spontaneously. Also, in most systems, the Lenard Jonz energy has played an essential role in the adsorption process, which can be attributed to the formation of π-π stacking between the antibiotics and the substrates. As can be seen from the composition of the interaction energies, two important elements that are crucial to the adsorption process are the vdW and electrostatic interactions. All three antibiotics, TMC, KMC, and AMC, have π electrons in their molecular structure, which makes it possible to form the π-π stacking with structural rings in MOFs. Overall, comparing the total energy of functionalized and pristine systems, the following stability order can be observed: KMC > AMC > TMC/F-MOF&MOF. Figure 5 illustrates the average of the total interaction energies obtained for each simulation system throughout 100 ns. Furthermore, as shown in Table 2, every system has negative energy values, suggesting ideal circumstances for the antibiotic pollutant to be adsorbed. The systems with the highest negative interaction energies among all systems are KMC/MOFs and KMC/F-MOFs, as confirmed by the present energy values. Consequently, KMC antibiotic molecules show superior suitability for adsorption on MOFs substrates. Notably, the enhancement of substrate functionality primarily arises from the increased number of contacts between the investigated molecules and the substrate. Our results confirmed that the stability of the antibiotics/F-MOFs systems is improved by metal-porous functionalized MOFs with imide groups. As a result, in comparison to the pristine MOFs crystal structure, the interaction energies between contaminant molecules and MOFs are enhanced in the presence of imide functional groups. This enhancement positively impacts the MOFs’ ability to adsorb antibiotic molecules with imide groups, thereby augmenting the MOFs’ capacity to adsorb antibiotics. This observation aligns excellently with Zhou et al.’s experimental work49, which demonstrated that MOFs materials can both exclude and detect tetracycline antibiotics in water, thus emphasizing their potential in wastewater treatment applications.

The total interaction energies obtained for each simulation system.

Li et al.50 established a theoretical and experimental foundation for creating effective adsorbents aimed at removing low concentrations of antibiotics. Their recent studies on modified MOFs primarily focused on enhancing MIL-101(Cr) by incorporating alkyl groups, which significantly improved its capacity to adsorb tetracycline from water. The findings revealed that MIL-101-dod exhibited the highest adsorption efficiency, successfully reducing tetracycline levels from 5 ppm to below 1 ppb. This research highlights the critical role of various interactions between MIL-101-dod and tetracycline molecules, suggesting potential pathways for developing new adsorbents tailored for antibiotic removal. Mon et al.51 provided a comprehensive overview of various synthetic strategies for water remediation, highlighting the significant potential of magnetic MOFs for effectively capturing pollutants from water. Their work elucidates how these advanced materials can be tailored to enhance adsorption capabilities, making them promising candidates for addressing water contamination challenges. By leveraging the unique properties of MOFs, such as their high surface area and tunable pore structures, researchers can develop innovative solutions for pollutant removal, thereby contributing to improved water quality and environmental sustainability.

Radial distribution functions

Furthermore, the radial distribution functions (RDF) of molecules at a distance ‘r’ from the adsorbent can be used to study molecular interactions. In this study, we evaluated how contaminant molecules, like KMC, AMC, and TMC, were distributed across the MOFs & F-MOFs substrate’s crystal structure. The following equation introduces the RDF:

The RDF, g(r), can be used to estimate the probabilities of finding a molecule at a distance (r) from a reference molecule. On the other hand, the density of molecules at a distance (r) from the reference molecule is represented by n (r). The width of the shell at distance r is shown by Δr, while the total molecular density of the system under study is represented by ρ. Significant insights into particle interactions are revealed by the RDF analysis of the systems under investigation in Fig. 6. The following order is observed for g(r) values in the investigated systems: KMC > AMC > TMC/MOFs & F-MOFs. According to the results of the RDF analysis, the majority of the antibiotic molecules in the systems under investigation are located close to the MOFs material’s surface once they have equilibrated. Close inspection of Fig. 6 confirms that in the RDF diagrams, the most significant peak was observed in the KMC-MOFs and KMC/F-MOFs systems. In this regard, at distances of roughly ~1.07 nm and 0.57 nm from the surfaces of F-MOFs and MOFs, respectively, the primary peaks of antibiotic contaminants (KMC) are prominently observed (refer to Fig. 6). This observation can be attributed to the robust interaction between antibiotic molecules and the active sites of MOFs and F-MOFs, which is due to π-π interactions and the creation of hydrogen bonds (C=O, C=N) between the antibiotics’ functional groups and the substrate. It is worth mentioning that including imide functional groups within the MOFs’ framework can effectively increase polar active sites of the substrate, resulting in their ability to exclude pollutants increases. In this manner, these findings exhibit a strong correlation with other results obtained throughout this study.

a MOFs substrate. b F-MOFs substrate.

Mean square displacement

To enhance the presentation of these findings, mean square displacement (MSD) calculations can be utilized. A measure of a particle’s displacement from a reference point over time is called mean square displacement, and it comes from statistical mechanics. MSD is an essential parameter for evaluating the efficiency of MOFs materials in adsorbing and removing pharmaceutical contaminants when utilizing MOFs and F-MOFs structures. The equation that follows can be used to determine MSD in order to study the adsorption behavior of antibiotic contaminants:

N is the number of equivalent particles over which the MSD is calculated; r is the particle’s coordinate; d is the required dimensionality of the MSD; rd (t˳) is the particle’s referenced location; and rd is the particle’s precise position at time t. The self-diffusion coefficient (Di) can be obtained from the long-time limit of the mean squared displacement (MSD) using the Einstein relation:

As seen in Fig. 7, the MSD curve for the KMC-MOFs & KMC/F-MOFs system has a lower slope and less self-diffusion coefficient than the other antibiotics/MOFs &F-MOFs systems. The adsorption of molecules onto the substrate surface leads to reduced mobility due to the formation of hydrogen bonds and π-π interactions. The penetration coefficient of the investigated systems can be ranked as follows: KMC-F-MOFs/MOFs > AMC-F-MOFs/MOFs > TMC-F-MOFs/MOFs. The lower Di value of the KMC/F-MOFs systems could be due to the penetrating of antibiotic into the pores of substate. Our results indicate that the slope of the MSD curve for the TMC molecule is higher compared to others, likely due to reduced hydrogen bond interactions between TMC and the substrates under investigation. The diffusion coefficient values for the adsorption of KMC molecules on MOFs and F-MOFs substrates are ~0.006 and 0.001 × 10-5 cm2/s, respectively. Conversely, systems with the lowest adsorption value of pollutant molecules are related to TMC antibiotics with diffusion coefficients at about 0.034 and 0.010 × 10-5 cm2/s for adsorption on MOFs and F-MOFs substrates, respectively. The RDF diagrams in Fig. 6 support these findings by indicating that TMC molecules may be present in this system at a higher distance from the adsorbent than in other systems. In general, our results confirm that MOFs and F-MOFs substrates prove to be well-suited for the adsorption of antibiotic contaminants. This is owing to the myriad advantages of these substrates, encompassing a sizable surface-to-volume ratio, robust adsorption capability, favorable surface reactivity, and outstanding surface properties.

a MSD patterns for drugs around the MOFs, b MSD patterns for drugs around the F-MOFs.

Number of contacts

Table 2 displays the average number of contacts between antibiotic molecules and the MOFs during the last 10 ns of the simulation. As depicted in this table, across all systems where MOFs are functionalized with the imide group, there is a notable increase in the number of contacts between the antibiotics and the adsorbents. This underscores that the functionalization of the substrate with the imide group has augmented the absorption of antibiotic contaminants from the aqueous environment. In addition, the increased contact between the AMC molecule and the substrates can be attributed to its higher molecular mass, greater number of atoms, and larger contact surface area. This phenomenon stems from the presence of distinct structural cavities within the molecularly engineered MOFs materials. These cavities’ active sites selectively house AMC molecules through electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonds, thereby enhancing their adsorption or exclusion within the framework’s configuration. This observation confirms that the presence of the imide group enhances the surface properties of the substrate, thereby facilitating the adsorption of antibiotic contaminants.

The number of hydrogen bonds

Figure 8 presents data on the hydrogen bond (HB) counts for each system under investigation. It is evident that the number of hydrogen bonds between the antibiotics and the water reduces following the adsorption of antibiotic pollutants on the surface of MOFs & F-MOFs materials. This fact demonstrates that contaminants are adsorbed on substrate surfaces and the hydrogen bonds between antibiotic molecules and substrate active sites form. The analysis of hydrogen bonding shows that the target molecules can form hydrogen bonds with both donor and acceptor sites on the MOFs & F-MOFs surface. The formation of HBs may improve system stability and substrate adsorption capability52,53, according to theoretical54,55,56 and experimental data57,58,59. Close inspection of this analise shows the following order for the number of hydrogen bonds between F-MOFs and antibiotics contaminants: KMC > AMC > TMC.

HBs between water and antibiotics in studied systems.

Notably, fewer hydrogen bonds in the TMC-MOFs & F-MOFs system can be due to fewer heteroatoms in the structure of TMC antibiotic in comparison other antibiotic molecules. Therefore, it can be concluded that the hydrogen bond between the MOFs materials and antibiotic driving forces can contribute to the adsorption of antibiotic molecules onto the adsorbents. Nevertheless, our results show that Lennard-Jones interactions play a more important role in the adsorption of pollutant molecules.

The number of hydrogen bonds between adsorbates and water decreases by functionalizing the substrate. The average number of HBs is shown in Fig. 9. These findings indicate that substrate functionalization enhances the adsorption of antibiotic molecules onto the substrate surface, resulting in a reduction in the number of hydrogen bonds between pollutant molecules and water.

The average of number of hydrogen bonds between the KMC/AMC/TMC molecules and the water molecules.

Density

The density profile (ρ) can provide valuable information about the concentration of adsorbate molecules around the substrate. Meanwhile, we have analyzed the density profile of antibiotic molecules within the KMC/AMC/TMC-MOFs & F-MOFs system in the z-plane configuration. Figure 10 depicts the density distribution of antibiotic molecules across the substrate. As the density of antibiotic molecules increases, the removal efficiency of the contaminates, and the concentration of molecules around the adsorbents increase. Our results show that KMC has the highest density value at a distance about 1 nm from the MOFs/F-MOFs surface (about ~71.19 Kg m–3 and 77.14 Kg m–3) due to more π-π stacking interaction and formation of hydrogen bonds. The rise and fall of the density diagram are also due to the pores structure of the substrate. The different oscillating density peaks for each system are shown in Fig. 10, indicating the existence of layers of metal framework pores inside the MOFs that contain water molecules. The distribution of water molecules close to the adsorbents shows many peaks and higher symmetry, suggesting that MOFs & F-MOFs substrates affect the adsorption of antibiotics. Furthermore, the appearance of peaks within a small range indicates a local hydrogen bonding structure. Notably, in the KMC system, the first peak of the density profile is observed at ~0.5 nm, while in other systems, this peak appears around 0.75 nm. Additionally, the largest peak in the density profile is likely due to the reduced number of water molecules surrounding the substrate structure. Therefore, it can be concluded that the substrate exhibits a high density of hydrogen bonds and π-π stacking interactions with the antibiotic molecule contaminants. Symmetrical density shows the probability of drug presence around the substrate. In fact, it states how the concentration of the antibiotics is at a certain distance from the surface of the substrate. In this principle, the average density in the F-MOFs systems are about ~F-MOFs/KMC = 43 Kg m–3, F-MOFs/AMC = 26.32 Kg m–3, and F-MOFs/TMC = 28.77 Kg m–3, and in MOFs systems for KMC, TMC and AMC are approximately ~32.14, 24.67, and 26.06 Kg m–3, respectively. This evidence indicates that antibiotics in functionalized systems exhibit greater activity compared to pristine adsorbents, leading to accelerated adsorption of the antibiotic molecules onto the framework materials during the process.

The density profile molecule around of the MOFs and F-MOFs substrates.

Free energy analysis

The metadynamics simulation was conducted to investigate the FES of the interaction and stability of KMC molecules with MOFs and F-MOFs substrates. The FES, depicted in Fig. 11, represents the separation between the MOFs and F-MOFs substrate materials and the center of mass of the antibiotic molecules. The results indicate that the free energy in the adsorption process increases when the antibiotic pollutants adsorb onto the substrates during the metadynamics simulations. The KMC/MOFs&F-MOFs systems encounter energy barriers and local low points as they strive to reach their overall minimum energy states. At their global minima, the free energy values for the KMC/F-MOFs and KMC/MOFs complexes are approximately –298.32 kJ mol–1 and –275.99 kJ mol–1 systems, respectively. The results indicate that the FES progressively becomes more negative as KMC molecules more migrate toward the active sites of F-MOFs cavities during the adsorption process. Recent computational studies indicate that MOFs materials are efficient in excluding pollutants from surface water, positioning them as viable candidates for water purification.

The FES patterns for transferring KMC antibiotic molecules onto the MOFs and F-MOFs substrates.

Discussion

The adsorption of medicinal pollutants onto or into the MOF in an aqueous environment was investigated using simulations based on molecular dynamics and metadynamics. In conclusion, our research has demonstrated the efficient use of porous MOF structures with large cavities for the adsorption of antimicrobial pollutants from water, as well as the examination of their host-guest interactions. The negative surface charge of the MOF renders it conducive to the adsorption of drug molecules, enabling the removal of antibiotic pollutants from aqueous mixtures. Our findings demonstrate that antibiotic molecules spontaneously adsorb onto the substrate across all investigated systems. Especially, in KMC systems, antibiotics adsorb more onto the MOFs&F-MOFs than in other systems. The analysis of interaction energies highlights the significance of Lennard-Jones interactions in the adsorption of antibiotic molecule contaminants on the substrates. All of the systems under investigation attain equilibrium before 10 ns, according to RMSD charts. The results of other analyses, including the density, mean-squared displacement, RDF, and number of hydrogen bonds, also support the interaction energy analysis conclusions. Among the studied systems, KMC-F-MOFs exhibits the highest average number of contacts, indicating increased interaction. Conversely, this system demonstrates the lowest penetration coefficient, signifying efficient adsorption onto the substrate. The density diagram illustrates the distribution of drug molecules around the substrate. Hydrogen bonds analysis confirms that functionalizing the substrate enhances the formation of hydrogen bonds between antibiotics and substrate. Collectively, these findings suggest that MOFs present a viable solution for removing antibiotics from aqueous environments. Our metadynamics simulations, intended to analyze adsorption behavior, demonstrate that the global minimum of the free energy level is affected by the active centers on the adsorbent surface.

Responses