The challenge of monitoring policy mixes for reducing emissions from buildings

Introduction

Reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050—the stated long-term goal of the European Union (EU)—means that emissions will need to decline to nearly zero in virtually all policy sectors. To understand current emissions and potential ways to reduce them, countries have typically focused on energy production, including for example the emissions from power plants, and to some extent consumption via policies on energy efficiency. When emissions are approached from the perspective of consumption, however, buildings emerge as a particularly important energy consumer. According to the United Nations (UN), the buildings sector, including construction materials, accounts for about 34% of global energy usage and correspondingly 37% of global emissions1. These emissions are even greater when considering the entire life cycle of buildings2.

The great diversity of buildings—ranging from small and large residential buildings all the way to non-residential ones, including for example schools, hospitals, office buildings or factories implies that addressing emissions in this sector remains challenging3. In the use phase, some buildings generate emissions directly from, for example, heating or cooling, using oil, gas or biomass, while in other cases whole cities or neighbourhoods may be served by single emission sources through, for example, district heating or electricity from solar photovoltaics. This creates a highly distributed nature of consumption-related emissions in the buildings sector, which differs from the energy sector. Centralised energy production typically has a small number of concentrated emitters (i.e., power plants) that have largely been regulated through the EU Emission Trading System (ETS). In the building sector, many emissions, which are in part accounted for in other sectors, such as energy, transport and industry, can ultimately be traced back to buildings.

The buildings and the energy sectors thus interact. This interaction is seen in individual buildings that use their own heating, but still depend on grids (in Finland almost exclusively electricity, but in Germany mainly natural gas and also district heating), for lighting and in the future also for charging electric vehicles. Interaction arises in large districts that almost exclusively use centrally produced energy and thus cause ‘their’ emissions in the energy sector, and in all kinds of hybrids of these extremes. The buildings sector is furthermore changing on many fronts, for example in some countries we are observing a small boom in ground source heat production in urban areas with housing companies reducing or closing the use of district heating, thereby changing the interaction with the energy sector through increasing electricity demand. For example, statistics of the Finnish Heat Pump Association SULPU indicate that annual investments in ground source heat pumps have nearly doubled between 2016 and 20234.

Against this background, it quickly becomes clear that a single policy instrument alone cannot address the variegated emissions in the building sector, broadly defined. Indeed, at the UN and the EU level, as well as in Finland and in Germany—our focus governance levels/countries in this paper—numerous policies have been put in place to address the direct and indirect emissions from buildings. Gaining an understanding of the systems in place to track existing policy mixes, which address different governance levels from the local to the international level, as well as gauging their cumulative efforts and effectiveness is therefore a crucial task, not only to understand what is going on, but also to drive potential improvements and adjustments with a view to the net-zero target.

In the EU, several monitoring and reporting obligations have been put in place to track individual policies and measures steering the building sector towards a low carbon future. In 2018, many different reporting obligations became part of the Regulation on Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action ([EU] 2018/1999). This regulation also incorporates the landmark “Monitoring Mechanism” of the EU, which has formed the basis for reporting emissions at the European level and biannually onwards to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)5. It is a key tool for the EU and its Member States to track and understand policy development. Many countries, including Finland and Germany, also have reporting obligations as part of their national Climate Change Acts.

Whilst mixes of climate policies have generally received increasing attention6,7, the policy mixes in the building sector have often been neglected (but see refs. 8,9,10,11,12,13). There is even less reflection of what the use of policy mixes implies for policy monitoring in the EU and in its Member States, a gap that this paper begins to address. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines policy monitoring as “a continuous process of collecting and analysing data to compare how well a project, programme, or policy is being implemented against expected results.”14 Relatedly, reporting may then be understood as the transfer of information from monitoring between different actors and in some cases governance levels. A particular challenge lies in the comparability of monitoring data and information from different countries. Doing so requires transparent descriptions of what the actual policies and measures are. While a unique definition has remained elusive so far, we stress the importance of a clear operational interpretation of what policies and measures are. This is also an issue for the overall framing of monitoring at the UN level, even though the UN does not have any substantial power to decide on specific policies for the building sector. We therefore reflect on policy monitoring and reporting systems in place at the UN, although our main focus is on the EU level, as well as on Finland and Germany.

Conceptually, we depart from desirable aspects of policy monitoring and reporting systems identified in the literature. Many of these aspects have been discussed individually over time, but they have not yet been brought together in one framework. These aspects include the use of clear operational interpretations of what constitutes a policy or measure, the ability to take stock and provide qualitative descriptions, the availability of quantitative indicators and the consideration of interactions between policies and aggregate impacts. In addition, desirable aspects include overarching issues of timing, durability and justification of monitoring systems and activities. We use this framework, described in more detail in the Section on methods, to assess existing policy monitoring and reporting systems of the UN, the EU, Finland, and Germany, including their key characteristics. We examine what information they provide on the policies with a focus on the understanding of the policy mix in the building sector.

The monitoring and reporting mechanisms we examine have different roles in a multilevel governance setting. The UN sets the general framework for climate policy and its monitoring and reporting and is expected to serve general global policy development. The EU, Finland and Germany have been considered forerunner jurisdictions in the fight against climate change15. These jurisdictions have been engaging in long-standing efforts to address emissions from the building sector and they are also historic climate policy monitoring and evaluation leaders16,17. Their monitoring and reporting mechanisms can thus be expected to play an instrumental role in tracking and adjusting specific policies. Differences arise due to geographical characteristics, the size of the jurisdictions, governance structure and the energy sector. Therefore, these jurisdictions are well-suited to illustrate various aspects and challenges in addressing emissions from the building sector in a West European context.

The paper is structured as follows. “Results” unpacks the empirical findings of this paper, namely the policy monitoring and reporting systems that focus on buildings policy at the UN and the EU level, as well as in Finland and Germany, from a systematic and comparative perspective. Given that Finland and Germany are both EU Member States, looking at the multi-level monitoring and reporting systems in the building sector is necessary. We focus on the headline reporting streams that emerge from key EU legislation, as well as from national climate legislation, including the factors that affect monitoring and reporting. “Discussion” discusses the findings and the state of monitoring buildings policy and offers conclusions with a view to future research and practice. “Conceptual Approach and Methodology” provides details on the conceptual approach and our research methods.

Results

This section presents our results, which demonstrate that decades of experience and adjustment have produced increasingly mature monitoring and reporting systems from the UN to the EU and to countries like Finland and Germany. The coordination between governance levels has improved notably over time, but the focus on individual policies and measures–including on buildings—is a more recent phenomenon that is still developing. Insights on interactions between policies as part of a broader, building-related policy mix, remain limited. However, new reporting formats, such as more comprehensive reports in the context of the Paris Agreement and its emerging downstream governance structures, show some promise in enhancing insights on interactions in the future.

Monitoring buildings policy at the UN and the EU level

At the international level, the UN has in the UNFCCC set up the overall frame for states to collect and pool their emissions and policy reporting to understand global progress towards their climate targets. International coordination of climate action efforts necessitated reporting of the relevant monitoring data from lower to high levels to assess overall progress18. While the focus was initially on calculating and reporting greenhouse gas emissions (whose IPCC-based technical protocols are fairly well-developed by now), reporting on climate policies emerged in the 2000s as an additional element. Reporting provides critical information for decision-makers at different levels19.

The UNFCCC required from developed (Annex I) countries both a national communication every four years and a biennial progress report under the so-called monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) framework. In addition, Annex I countries were obliged to submit an annual greenhouse gas emissions inventory by 15 April each year20. Under the enhanced transparency framework of the Paris Agreement, all parties are required to submit “Biennial Transparency Reports” from late 2024 onwards, which extend the previous biennial reports to all parties so that the former differentiation of developed and developing countries by the means of annexes is abolished—although some exceptions for very small (island) states remain. The detailed instructions make clear that the reporting covers all efforts, including national circumstances, and specific policies and institutional frameworks, to reduce greenhouse gases21. In so doing, the parties must also specify relevant indicators to monitor their policies, including emissions22. Applied to buildings, this implies data on emissions from existing structures and modelling to explore future developments. Furthermore, compared to the earlier biennial reports, the new and stronger expert review is one of the key enhancements. We thus observe a greater policy focus and an effort to bring the development of greenhouse gas emissions and that of policies closer together.

At the EU level, policy monitoring in the climate and energy sectors has a decades-long tradition5 and received even greater attention with the Energy Union and Climate Action Governance Regulation of 2018 ([EU] 2018/1999). The link with the Governance Regulation makes the EU’s interest in policy monitoring different from that of the UN. The EU has a legal mandate to introduce instruments for the governance of specific sectors, whereas the UN does not. The Regulation is therefore important in the EU’s own policy making, while it also ensures that policy planning, monitoring, and reporting in the EU remain synchronised with the ambition cycles under the UNFCCC/Paris Agreement. The monitoring focus has always been on (legally mandated) ex-ante assessments and reporting, but over time the European Commission and the European Environment Agency—which operates the climate policy monitoring system in practice23 – have begun to elicit more ex-post policy assessments on a voluntary basis. These have, however, only emerged slowly and partially24. The Governance Regulation has also introduced new national Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs), which elicit more holistic assessments of progress.

Annex VI of the Governance Regulation on “Policies and Measures Information in the Area of GHG Emissions” details that EU Member States have to provide both qualitative and quantitative information. The reporting should provide information on objectives and a short description, the policy instrument type, the implementation status, indicators to monitor and evaluate progress over time, and quantitative estimates of ex-ante and ex-post effects (though especially the latter often only “where available”), as well as policy-based costs and benefits. While the regulation does not include a clear definition of what a policy or measure is, it remains in line with Hall’s understanding to focus on instruments25. Some qualitative description is also to be included, as well as various quantitative indicators to include policy effects. The reference to “groups of policies” and the demand for “information regarding the links between the different policies and measures, or groups of measures […]” indicates that interactions have been recognised as an issue. The possibility of reporting in bundles was first introduced in the 2013 Monitoring Mechanism Regulation26. For buildings, Article 2a of the Governance Regulation (2018/1999) requires data-driven, annual emissions analysis (base year 1990) with a view to all existing buildings and an estimate of those that will be built in the future.

In addition, in the preparation of National Energy and Climate Change Plans (NECPs – Article 8, Section 2c) Member States must report on “interactions between existing policies and measures or groups of measures and planned policies and measures or groups of measures within a policy dimension and between existing policies and measures or groups of measures and planned policies and measures or groups of measures of different dimensions for the first ten-year period at least until the year 2030.” The building-related reporting therein focuses on the realisation of national targets, considering the building stock of 2020 and new buildings onwards. Thus, the new reporting requirements have introduced a greater focus on interactions than before. The timing of the data provision of the Governance Regulation is in synch with the UNFCCC reporting and provides yearly greenhouse gas data and relatively frequent policy-based data (see Table 1). Given that the policy-based monitoring system has its origins in the early 1990s and has existed with its main features since the early 2000s, it has already proven a good level of durability.

Additional monitoring requirements that link with the Governance Regulation emerge from the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (Revised as 2018/844/EU) through the so-called Long-Term Renovation Strategies (LTRS)—which will be called “National Building Renovation Plans” from 2025 onwards. These strategies are part of the NECPs, and LTRSs must include a roadmap with measures and measurable progress indicators, as well as indicative milestones for 2030, 2040 and 2050. The LTRS are prepared every five years (starting in 2014) and cover the building stock of 2020. The plans should also include an estimate of the expected energy savings and wider benefits and the contribution of building modernisation to the EU’s energy efficiency target.

Domestic monitoring of buildings policy in Finland and Germany

At the national level, the Finnish Climate Act (423/2022) requires the government to provide an annual public Climate Report to Parliament27 which includes a section on building-specific heating, with a description of key policy measures in place. The annual Climate Report is coordinated by the Ministry of the Environment with contributions from all relevant other ministries and expert organisations27. Its purpose is to provide an overview of climate policies. Thus, the Report examines trends in emissions and sinks, sufficiency of planned measures to achieve the emission reduction targets, need for further measures, and implementation of targets and measures as specified in national plans.

The institutional arrangements in place support a common understanding of the key challenges and policy instruments that form the base for policy action in the climate policy planning system required by the Climate Act. Buildings is a particular sector with many actors and a wide range of policy instruments arising from many separate policy domains (including energy policy, taxation, building regulations, and land use planning), with many potential interactions. Each of these domains has developed its own monitoring forms and traditions. Developing coherent monitoring of the policy mix is therefore challenging. There is however a need for such monitoring due to, for example, the requirement for EU countries to adopt a long-term renovation strategy (see above).

In practice, the monitoring has been led by the Finnish ministries, with specific monitoring tasks delegated to expert organisations that have contributed with estimates of the emissions as well as assessments and evaluations of policy measures. In the case of climate and energy policy monitoring, the overall coordination has been with the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, but the Ministry of the Environment has been responsible for the specific estimates concerning the built environment. Expert organisations provide data on the composition and evolution of the buildings stock (Statistics Finland, Finnish Environment Institute [Syke]), modelling of the building stock and its emissions (VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland and University of Tampere), and data as well as assessments of energy efficiency development in the building stock (Motiva Ltd, a state-owned expert organisation for resource and energy efficiency).

In Germany, there have been two ways in which climate policy monitoring and reporting have been pursued: First, the reporting to the Monitoring Mechanism and the UNFCCC has typically been conducted by the means of reports, which are contracted out to research organisations. These reports enabled organisations such as national Ministries and the Federal Environment Agency to ensure compliance with Germany’s reporting obligations. Meanwhile, new incoming legislation introduced additional monitoring and reporting requirements, especially in the case of the national energy transition or the Energiewende. Here, regular monitoring cycles were established, coupled with an expert committee to assess the findings28. A substantial additional drive for reporting climate action policy efforts emerged from the German Climate Change Act (GCCA), which was first passed in 2019. Crucially, the GCCA combines sector-specific targets (including one for the building sector) with a monitoring mechanism, which from 2022 produces reports every other year, including with a view to the different policy sectors that the act covers. The reporting also feeds into the Energy Union reporting29. An interdisciplinary group of experts reviews the government reports and provides statements to Parliament. Overall, we can therefore observe a turn towards a more monitoring-based governance approach in Germany, which emerged at the expense of enforceable sector-based targets in a 2023 reform30. Table 1 summarises the monitoring arrangements with a view to the building sector at the UN and EU levels, as well as in Finland and Germany.

Understanding the role of the United Nations monitoring system

The review and stock-take exercises of the Paris Agreement seek to provide information at intervals that can influence international negotiations. Originally, the UNFCCC required National Communications every four years but since 2011 biennial reports are required to ensure up-to-date information (Decision 2/CP.17). At the international level, monitoring data are reported in national communications (NCs) and Biennial Reports (BR), which are subject to in-depth reviews. The reports follow a standardised structure and provide tabular data on specified indicators. International expert teams conduct the in-depth reviews, coordinated by the UNFCCC secretariat. They aim to provide a comprehensive, technical assessment of a Party’s implementation with a view to the commitments. A report documents the review to facilitate the work of the Conference of the Parties (COP) in assessing the implementation of Party commitments. The review reports strive to facilitate comparison of information between the NCs of the Parties31. Recent reviews of Germany and Finland provide an overview of both the national communication and the biennial report32,33.

The national communications, the biennial reports and their reviews strive to provide an overview of climate action in all relevant sectors (Table 2). For the building sector, detailed data identify specific trends and issues (such as the excess emissions from buildings in the case of Germany). The recognition of policy mixes and interactions between policies and levels of governance is only emerging. The UNFCCC reports for Finland and Germany32,33 mention sets of policies but do not include any explicit consideration of possible interactions. Yet, there is a demand for such information on interactions. For example, the latest IPCC report on buildings recognises the importance of policy mixes (Section 9.9.3 in ref. 34), but the accounts of different policies and policy mixes remain descriptive rather than analytical. Detailed evaluations of the effectiveness of policy mixes for the buildings sector in different contexts are not yet available.

Assessment of the EU system

The European Environment Agency’s repository (‘EEA database on greenhouse gas policies and measures in Europe’)35 provides monitoring data for a broad audience36. The database not only contains policy-specific data from each EU country (and others, which are part of the monitoring process), but also allows sorting the data according to specific, content-based categories by policy objectives. Our focus is on relative projected policy effectiveness in each country in the building sector. This approach enables us to assess orders of magnitude rather than absolute reductions, which provides relevant information when considering policy mixes. Separating in detail the specific quantitative contribution of each policy or measure in a mix is rarely feasible. The overall result in terms of emission reductions in the whole sector is the important target. The projections associated with specific policies helps to identify crucial building blocks of the mix.

Quantitative data on policies and measures

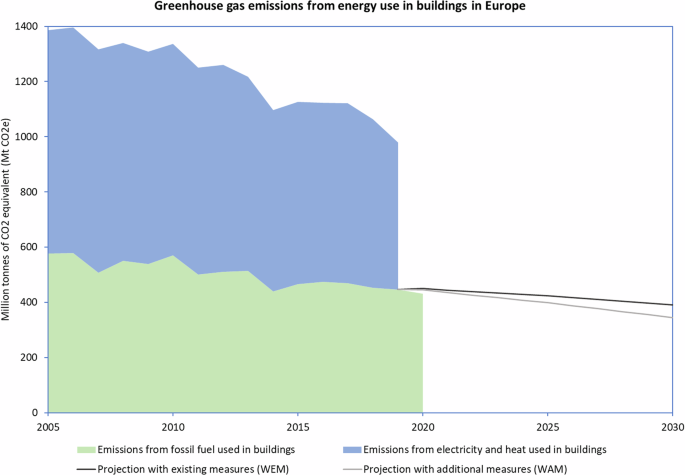

The overall development of GHG-emissions from the building stock shows a modest declining trend in Europe (Fig. 1). Finland performs above average and Germany is on an average track (Fig. 2 and Table 3).

European wide estimation of greenhouse gas emissions from energy use in buildings in the EU (Source EEA https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-energy/assessment). Projections apply to the emissions from fossil fuels used in buildings.

Source: Long-term renovation strategy 2020-2050 Finland and Projection Report for Germany 2023/German Environment Agency.

In the period 2005–2019 Finland was 6th in relative emission reduction and Germany 16th. In projected relative emission reductions with additional measures our case countries end up 11th and 12th, respectively (Table 3).

A comparison of the quantitative reporting of Finnish and the German policies and measures in the EEA database reveals that Finland reported more than three times as many policy instruments as Germany did (see Table 4). But the policy mix also differs: While Finland mainly focuses on information-based instruments (6), followed by regulatory instruments (5) and economic instruments (4), Germany reported 3 fiscal instruments (compared to 1 in Finland), 2 regulatory instruments and only one information-based instrument. It should of course be noted that, as mentioned above, additional, building-related policy efforts may also be part of other policy instruments with a broader remit.

An indicator of individual policy and measure effectiveness can be obtained by calculating how large a share of the emission reduction in the sector is projected to be achieved with a particular policy or measure. The most significant measures appear to differ between the countries. In Finland, building and repair regulations (minimum standards) are estimated to be particularly relevant (Table 5) whereas voluntary, but financially encouraged (KfW/BAFA programmes/soft loans) measures are projected to have the greatest impact in Germany (Table 6). Both countries have financially encouraged energy efficiency actions and minimum standards based on law, but the effectiveness in reducing total emissions is still different. All these actions are based on the same EU directives (Directive (EU) 2018/844) but may not be directly comparable. What is also noticeable is that for Finland, the estimations for 2040 are still very open, while Germany expects most effects from pricing of CO2 emissions in the heating and transport sectors. There are several policies and measures with no or null projections (Tables 5 and 6).

An important difference between the two countries is that the energy emission intensity of Finnish electricity generation is low, reaching 66 gCO2e/kWh in 2022, whereas in Germany the comparable figure was still 366 gCO2e/kWh37. In Finland, policies shifting heating to (partly) electric sources with the help of, for example, heat pumps, thus decarbonise energy use of buildings much faster than in Germany. The Finnish electricity production has largely been decarbonised through a mixture of renewable energy and nuclear power. In Finland, 94% of the electricity production was fossil free in 2023, including the electricity generated by industry38. The main energy source for fuel-based district heating production in Finland is biomass. In 2022, the share of wood and other bio-based energy sources was 54% whereas coal, peat, oil and natural gas together accounted for 40%. District heating emissions have decreased significantly over the last decades39. In both countries, policies and measures for energy efficiency help in reducing emissions, but in Germany it is even more important (Table 4) due to the large share of fossil fuels in energy production. Fossil fuels (grey bars) still dominate energy sources for heating buildings, primarily consisting of natural gas and heating oil (Fig. 2). Additionally, the heating infrastructure sets certain boundaries for cost-effective measures. While this is supposed to change over time, current projections still envisage a substantial share of natural gas and oil in the building sector, making measures that increase energy efficiency very important in corresponding efforts to decarbonise. See Fig. 2.

Overall, the analysis shows that the most significant effects are expected to come from instruments that affect a large share of buildings now and in the future, with relatively little envisaged change in the instrument mix as per the projections presented here. Building regulations in Finland are a case in point. However, policies decarbonising the energy production (both electricity generation and district heating) are a crucial component of the policy mix, but not visible in Table 6. Regarding Germany, the most significant instruments must also affect a prominent share of the building stock, but in addition actions affecting the general energy production are a crucial part of the policy mix for buildings.

The interactions in the policy mix appear in the defined emission coefficients for heating, which largely determine the effectiveness of the measures that influence buildings and their use. For example, measures that encourage a shift from oil-based heating to electric heating have different impacts on emissions depending on how the electricity is produced and whether electricity is used directly for heating or to run heat pumps that extract heat from the air, ground, or waste heat (such as wastewater, cooling water, or ventilation exhausts).

Some policy measures are inherently weak in terms of direct emission reduction. Thus, the effectiveness of information guidance generally comes out as low in quantitative monitoring—as can be seen in the case of energy advice in Finland and the exemplary role of federal buildings in Germany in the data analysed here. One reason is that the real effects of such instruments may be almost impossible to anticipate, but also because the effect is not necessarily large. However, in a policy mix they may still play an important role in preparing the ground for the adoption of the measures that have a more direct impact on energy efficiency and emissions.

The contents of the country reports

In addition to the quantitative data, Finland and Germany have provided reports that detail their methodology and descriptions to arrive at the quantitative data. In this section, we examine what information they provide on policies and measures dealing with buildings.

Finland

The Finnish report contains a specific section on “Energy use in residential and other buildings.”40 In 2020, district heating accounted for 45% of the heat energy use, and about 65% of emissions from heating as district heating is based on a mixture of fossil (including peat) and renewable fuels, mainly wood. Heat pumps were the second most important heating source with 17% of the heat energy use, but its share of emissions is low as electricity production has been largely decarbonised. The direct use of fossil fuels caused about a fourth of the emissions from heating. The main fossil fuel is oil, as natural gas is hardly used at all in building-level heating systems. In 2020, oil boilers accounted for 7% of the energy use in detached houses. Since then, as policy measures have reduced the use of oil, the greenhouse gas emissions from heating of private households fell from 2018 to 2021 by 23%41 (greenhouse gas emissions inventory). The energy efficiency of new houses has also improved as the implementation of the Directive on the Energy Performance of Buildings (EPBD) led to a revision of energy regulations in 2017 and nearly zero-energy regulations for new buildings were given. The new regulations entered into force as of 1 January 2018. As noted above, nearly half of the energy used for heating is produced in installations that are regulated through the ETS. The projections suggest that the regulation for the energy performance of new buildings entails about 6 million tonnes of annual emissions reductions of CO2-equivalents by 2030. Almost all emission reductions will take place in the EU ETS sector through the reduced use of electricity and district heat.

Finland submitted its LTRS to the EU in 2020 and it follows the EPBD 2018/844/EU revision and covers the 2020 existing building stock. The main goals of the Finnish strategy are to decrease the energy use of the existing building stock by 51% and the related CO2 emissions by 92% by 2050. The factors impacting the decrease of energy use and emissions are climate change, removals of buildings from the building stock, retrofitting and building maintenance, change of heating sources in buildings, and decreasing emission intensity of electricity and heating production. The key policy measures supporting the Finnish LTRS are improvements of energy performance in renovations and alterations, phase-out of oil use in heating and related policies as well as retrofitting subsidies.

Germany

The German qualitative report is based on a large modelling study, which details methodologies and results. It contains a sector-specific section on buildings42. While the list and description of different measures is relatively long—ranging from economic and fiscal incentives to regulations, obligations and changing in spatial planning activities, the authors detail on p. 204 that they only quantified the most effective measures, while for many other measures, which are included in the qualitative description, no quantifications of projected impact were produced (hence explaining the comparatively low number of instruments in Table 6). The reasons for a lack of quantification reach from lack of necessary data to the difficulty of estimating cross-sectoral instruments (p. 204). With a view to the effect of measures on individual buildings, the report also considers interactions, because a simple addition may not be reasonable where multiplication amounts to a better effect descriptor (p. 205). In this modelling study, the estimation of effects starts with January 2020 (p. 207); for some measures that only take effect later, the start date was adjusted correspondingly.

Germany also submitted its last Long-Term Renovation Strategy in 2020, detailing that the country seeks to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the building sector by 67% by 2030 (compared to 1990). It focuses on energy performance as a core indicator and stresses how an instrument mix is used to achieve the goals.

Fulfilment of the monitoring criteria

The monitoring and reporting required by EU-legislation fulfils many of the key criteria that are relevant for individual policies and measures. The monitoring makes it possible to track the evolution of single policies and measures in the building sector and gives a view of the overall context. The policy mix is, however, not tracked as a set of interacting pieces, but mainly as an aggregate (see Table 7).

The Finnish and German Climate Acts mandate regular public monitoring and reporting to national Parliaments. In the Finnish Climate Act, annual reporting to Parliament reflects the continuous policy development in the climate field. The data and narratives broadly follow the international and EU monitoring and reporting, but the narrative sections provide some details that are not part of the EU or UNFCCC monitoring and reporting. For example, in Finland the report documents key policy measures in place for building-specific heating and detailed descriptions of the evolution of specific emissions such as those from light fuel oil by sector in building-specific heating and total emissions from building-specific heating in 2005–2021.

The domestic reporting is consistent with the monitoring and reporting to the UNFCCC and the EU. Its durability is therefore strong, and part of the justification arises from the need to provide reports internationally. The national reports are formulated by the government in force and can therefore emphasise the priorities of the current government’s policies. The monitoring and reporting primarily serve the domestic policy debate. In Finland, the report is submitted to Parliament, but also made public and the national climate panel comments on it, too.

Likewise, the German monitoring is closely linked with the EU reporting requirements. Article 10 of the German Climate Change Act requires annual reports of emissions (also linking with the UNFCCC reporting requirements), which also considers immediate action programmes, and from 2021 onwards, a projection report every other year, in line with the EU Energy Union Governance Regulation. Therefore, the German Climate Change Act by and large simply restates the existing, international reporting requirements and sets a framework to meet them.

The domestic monitoring strives to cover the full range of policies and measures and notes the different effects this may have on emissions, but is by and large silent on interactions between the policies and measures. In the Finnish report, there is no reflection on interactions within the policy mix presented for reducing emissions from heating.

Discussion

Reducing emissions from buildings is challenging in part because the turnover of the building stock is small, typically in the order of 1–2% per year43, although the turnover of individual building components, such as heating systems, may be higher, given the right incentives. Measures reducing emissions from the existing building stock are therefore critical in the time frame of the Paris Agreement. Such measures are intimately linked with impacts on household consumption, personal preferences and needs, making them often challenging to implement. Energy prices that affect households are politically sensitive as costs of heating is an important factor in energy poverty44. The consideration of such interactions have until now been by and large absent from the monitoring reports and their reviews by, for example, the UNFCCC32,33.

Due to the many interconnections, the monitoring and tracking of the policy mix aiming at reducing emissions from buildings cannot be limited to the policies and measures that have an immediate impact on building stock emissions. The transition to low emissions from buildings calls for a diversification of policy instruments, or what has been called a “thickening of the instrument mix.”45 Such thickening demands that monitoring pays increasing attention to the interactions of the different policies and measures. We have shown that the current monitoring and reporting according to the UNFCCC requirements, the Energy Union Governance Regulation and national legislation are only beginning to explicitly recognise interactions between policies and measures, an aspect that will need considerable strengthening in the future. The IPCC also recognises this need34.

The current monitoring systems track energy use in buildings and by households, and aggregate emissions of the building sector–while embodied emissions remain obscure. It is further possible to deduce the impacts of, for example, the ETS on emissions from the building sector. The importance of the ETS and the whole energy system is highlighted by both Finland and Germany in the narratives supporting the quantitative monitoring. Less attention has until now been put on tracking, for example, affordability, energy poverty and other obstacles to the transition although there are plenty of observations of the impacts on socio-economic conditions on energy transitions in the jurisdictions we explored.

Some data on energy poverty are available through, for example, Eurostat46. When the policy mix changes by expanding the ETS to buildings47, it will become critical to monitor and report on the challenges of this transition. If states and the EU fail to gather socio-economic data that can be used to adjust the policy mix to reduce injustices, a loss of legitimacy for the transition to a low-carbon society is likely48,49. These dynamics are especially acute in the building sector, which has suffered from perceived housing shortages in recent years; we argue that it will be necessary to develop the monitoring systems to generate a broader understanding of these impacts.

In Germany, additional complications in specifying the policy mix arise because the federal states (“Länder”) may also put in place their own policies and municipalities may, for example, set standards for the buildings they own. In Finland, the regional variation in policies is smaller, given its more monocentric governance structure, but municipalities can still choose from different approaches in developing their own building and housing policy. For example, dense urban cities tend to focus on decarbonising district heating whereas rural municipalities can encourage combined heat pump and wood fuel heating in detached houses.

Some of the effects of policies and measures have not been quantified for lack of data or because they were too overarching in nature. In consequence, the number of policy instruments reported to the EU differs between countries (as we could see here when looking at Finland and Germany), but this may not always directly reflect the totality of measures applied in a country. In some cases, new instruments have been added in the monitoring/reporting efforts because the effect of the same procedure has undergone such a change that it no longer corresponds with the original description of the instrument. For example, in Finland, the assessment of the effectiveness of building regulations has been reported as two separate policies and measures in the PAMs database, i.e. the old regulations starting from 2003 and the renewed, starting from 2012. In Germany, the 2021 reporting cycle fell into a particularly dynamic time in this sector, with a new incoming national government, which began to re-work key pieces of legislation in the building sector to address climate change. The corresponding qualitative report reflects this dynamic to some degree, but of course, the most recent developments could not be included. Just looking at the quantitative data, one may find the differences in base lines, but also the different choices in policy instruments and expected impacts surprising, as one may expect more convergence from two northern European countries. But the extent to which these effects emerge from differences in reporting versus actual differences remains obscure. Looking ahead, it would be useful for the EU and Member States to develop common guidelines on which policy impacts should be quantified and what contextual background should be provided. For example, quantification could be made mandatory for policies that are expected to account for a prespecified minimum relative emission reduction. This could be complemented by brief explanations of how the policies have provided incentives to reduce emissions in the sector. Such demands would not represent an undue burden on reporting as it would be in the Member States’ own interest to have as accurate information as possible on its policy measures.

Ideally, data would be comparable across countries. This would be relevant both at the UN level and in the EU. For the UN and the UNFCCC, comparability is relevant to enhance peer learning. For the EU, the issue is even more pressing as policy development at the EU level is dependent on an adequate understanding of the effectiveness of existing policy mixes. However, current reporting practices appear to differ even in terms of their timelines, as shown by the data submitted by Finland and Germany: Most of the starting date of the instruments reported by Germany refers to 2020, a fact that is also clearly stated in the qualitative report, as mentioned above. Some of the instruments reported by Germany are still so new that they were reported for the first time (or only reported for the future when they take effect). The differences between Finland and Germany can therefore also be explained by the fact that some of Finland’s instruments have been in force for up to 20 years, and the magnitude of the results is then driven by cumulation. This is not to say that Germany has not had any instruments in the sector, but the cumulative (historic) effect of the instruments was not estimated in the 2021 reporting. Although annual effects are reported, it should be noted that measures that have been in force for a long time have always affected a larger number of buildings. The results are accumulated for every year until, due to removal, some of the buildings within the scope of the impact are removed due to old age, etc. Because of this, the assessment of effectiveness also includes expired instruments. For better comparability, harmonised baselines and reporting periods across countries would enhance the conclusions one can draw from the monitoring data, especially when looking across countries. Stechemesser et al. 50 demonstrated how standardised data can be used to identify points and policy change associated with significant emission reductions in a comparative evaluation across countries50. According the break detection analysis neither the Finnish nor the German building sector have achieved major breakpoints in emission reduction between 2000-2020, although a steady decline can be observed (Table 3).

The instruments discussed here have been changing quickly: For example, the full reporting under the GCCA mentioned in the introduction is not yet part of the data we could access. Furthermore, a proposal has been put forward by the EU Commission to extend the European Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) to include buildings and transport (European Commission n.d.) but EU Member States have also identified problems with the proposal. Also, the revision of the Directive on the Energy Performance of Buildings (EU 2024/1275) to include mandatory energy renovations according to a fixed plan (Article 3) originally met with opposition. For example, the Finnish Government argued that a part of the existing building stock, especially in areas suffering from depopulation, would require costly renovations that would be both unfair to the owners and economically inefficient as climate actions51. It stressed the importance of flexible national plans for the renovation of buildings. The adopted Directive emphasises the planning and includes exemptions to the mandatory energy renovations (Article 9). This highlights the necessity of strict but also flexible Europe-wide policies for sectors as diverse as that of buildings. Our observations are in line with scholars who state that “to increase the effectiveness […] and achieve common goals, a greater number of common objectives with mandatory compliance should be implemented, thereby establishing basic formulas and methodologies without neglecting the flexibility necessary for MSs to develop their own final guidelines that account for their unique characteristics” (Section 7)52.

In summary, our analysis shows that a key challenge for the monitoring of the policy mix relevant for buildings (Tables 5 and 6) is that current monitoring and reporting cover only partially the totality of efforts undertaken in each country to reduce emissions related to buildings and that insufficient attention has been attached to interaction among policies and measures. This means that the overall monitoring of emissions presents results of processes that are only partly understood—we see the total outcome, but do not necessarily how to best improve the policy mix. A first step would be to add reflexions on the interactions in the narrative descriptions supporting the monitoring results. This would deepen the understanding of breakpoints in the emission reductions that statistical analyses such as those of Stechemesser et al. 50 can reveal and thus help in the search for successful policy interventions50. A further step would be to extend the monitoring of the policy mix to the full life cycle of buildings. In addition to heating and the use of electricity, doing so would include policies affecting emissions from industry (production of concrete, steel and other building materials), transport, and waste (demolition, possible reuse)2. The monitoring of policies affecting these life cycle stages are partly covered in other sectors, but to fully grasp the policy mix relevant for reducing emissions from buildings, it would be appropriate to provide a synthesis.

Doing so would also help in bringing monitoring insights to bear in the policy process53,54. Beyond tracking individual indicators, it will be important to trace the trajectory of the transformation and ensure that countries are on the right path to reach long-term goals. In some countries, such as Germany, the available data to monitor the building stock are currently not sufficient to do so. One way to address the political challenges of such approaches would be to delegate monitoring to an independent agency and/or ringfencing resources for monitoring institutions over longer time periods. Meanwhile, maintaining productive connections with the political processes in which and through which monitoring and reporting institutions operate remains paramount.

Conceptual approach and methodology

Conceptual approach – monitoring and reporting policy mixes and their effectiveness

The proliferation of different policy approaches has created a growing need to understand the specific mixes that affect different sectors55. To perceive and analyse policy mixes and especially their dynamic developments, practitioners and observers need monitoring and reporting, which allow them to “see” and “track” policy developments and their effects over time56. Accurate data and transparent reporting allow for better evaluation of progress and identification of opportunities for improvement. Various monitoring processes already exist in a range of substantial policy areas, initiated both by the public and the private sector at different governance levels. In this section, we draw on public policy monitoring and evaluation literatures to conceptualise what policy monitoring and reporting systems ideally need to deliver to make policy mixes and their development intelligible.

In so doing, this section combines two important perspectives on monitoring and reporting, namely a focus on individual policies and measures, and a focus on the relationship between them. Apart from delivering data and information on individual policies and measures, theory holds that a monitoring system should also provide information on the interactions and coherence across different measures and instruments, including those that have a wider remit than buildings. In addition, in the multilevel governance arrangements of the EU, monitoring should provide information that is relevant at European, national, and even subnational levels. In the buildings sector, the subnational and local level are often crucial for implementation. For policy development, it matters to understand the key drivers behind successful decarbonisation of the building sector. In the following sub-sections, we focus on the key characteristics of policy-based operational interpretations, taking stock, qualitative descriptions, quantitative indicators, interactions and aggregate impacts, as well as timing, durability of the monitoring systems and justifying monitoring politically. Table 8 summarises these desirable characteristics and provides brief explanations of each.

Operational interpretation of policies and measures

Monitoring and reporting systems require clear specifications of what is being monitored and reported. Ideally, this would be based on conceptual and legal definitions of what precisely constitutes a policy or a measure. In practice, writing a universal definition to produce comparable policy monitoring data across countries remains an enormous challenge because of varying policy characteristics but also because of the wider context in which policies generate impacts57 points to the many meanings and nuances of the idea of a “policy” that have emerged in academic literatures. One of the reasons for different perceptions is that as a baseline conceptualisation, policies consist of objectives, instruments, as well as instrument calibration25. Clearly delineating what, precisely, an individual instrument or policy constitutes, thus remains challenging. Rather than proposing a new definition of our own, we stress for operational purposes the importance of ensuring that the monitoring system presents a clear operational interpretation of the policies and measures, based on legal text or guidelines. This is essential to produce consistent monitoring outputs over time.

Taking stock

An ideal monitoring system would account for the full stock of policies and measures in a specific policy domain, such as for example climate or buildings policy. It is not trivial to specify what constitutes a relevant policy and measure for the building sector because of its strong links with many other sectors such as energy and general fiscal policies. Full accounting does not necessarily mean providing the exact same information on each policy and measure. But it does mean that the monitoring system should capture the full extent of instruments that a government deploys to achieve certain goals in a specific domain. The monitoring system should contain sufficient information on each instrument and its role in the policy mix so that (external) observers may gain a realistic and comprehensive understanding of the policy effort and its effects. Some of this information may be presented in simple lists, which may in some cases be accompanied by additional quantitative data and/or more detailed, qualitative descriptions of the specific policies and measures (see below).

Qualitative descriptions

Various external and contextual factors can contribute decisively to policy success or failure, and thus require consideration58. These could be shifts in the broader context, such as, for example, the economic climate, but could also refer to more local conditions, including institutional and/or political, social, historical, or geographical circumstances, which may influence policy trajectories. An ideal monitoring approach does not describe all conceivable factors in excessive detail, but characterises the main factors that likely impact on a policy, or which are crucial to understanding how and why a policy works (or not). In the area of climate policymaking, particularly relevant contextual factors in existing evaluations include time, policy goals (intended), policies in other sectors, unintended policy outcome(s), external events and circumstances, geography, and scientific findings59.

Quantitative indicators

While not all policy instruments require quantitative data to describe their past and/or future impact, some level of quantification across the policy mix is necessary, especially for estimating cumulative policy impacts and to ensure comparability across instruments and, ideally, across actors—an argument that has also been advanced with a view to evaluation59. Useful and well-defined quantitative indicators such as the effects on greenhouse gas emissions enable comparisons of multiple policies. Additionally, estimations of cost or cost-effectiveness are frequently demanded to justify policies and measures. It is, however, often difficult to monitor policy costs, because important costs may be indirect, and their estimation may thus require dedicated studies rather than routine monitoring.

Policy monitoring and reporting needs to provide data on the domain and sector-specific context. In the building sector, estimations of the so-called “renovation rate” is an important way to characterise the progress of policies that aim at improving and accelerating refurbishment efforts in the building stock43. Energy renovations, in turn, are measures that improve the thermic properties of a building, such as adding insulation or changing windows. When such indicators emerge from quantitative modelling, the models need to be available in sufficient detail to understand inputs, model characteristics and corresponding outputs. Furthermore, data sources need to be made transparent.

A crucial element concerns baselines, meaning where to start one’s monitoring or which reference years to use to assess policy impact (especially with a view to estimating greenhouse gas reductions) and future projections, that is, how far into the future one seeks to project anticipated policy impacts. The monitoring of policy mixes requires tracking relative to the stated policy aims. In the area of climate change policy, greenhouse gas emissions comprise one of the key—but certainly not the only—indicator against which policy effectiveness may be assessed. Greenhouse gas emissions may be assessed ex-post, that is, retrospectively or ex-ante, meaning prospective estimations of future policy impact. Neither retrospective nor prospective assessments of policy-based impacts on greenhouse gas emissions tend to be particularly straightforward, given that many different and non-policy related factors (such as overall economic activity, environmental conditions, changes in population and so forth) may influence emissions development. Doing so typically involves modelling studies that compare different scenarios, but therefore also work with a range of assumptions to generate results. Therefore, comparing policy-based emissions reductions, which have been estimated using different models and scenarios, can be challenging.

Interactions and aggregate impacts

Monitoring systems that capture policy mixes need to account for interactions between individual instruments and for aggregate impacts. Positive interactions (synergies), which emerge when instruments mutually reinforce each other, may generate a greater aggregate impact than one may expect from an additive perspective60. For example, a combination of economic incentives for energy-related building renovations with permitting processes for building amendments that strengthen overall building stability may lead to solutions that enhance energy efficiency more than simple additive effects of the incentives or the permitting. Negative interactions (antagonism) due to, for example, lack of policy coherence, may on the other hand reduce the expected impact61. To properly assess policy interactions, it is necessary to document what is included in and what is excluded from the mix62. In modelling and ex-post assessments, system boundaries need to be specified so that instruments can be explored jointly rather than individually63. In statistical analyses of impacts, interaction terms should be included where appropriate. A unified nomenclature with precise operationalizations enables the continuous evaluation of policies and the evaluation of the interaction between the overall effects. The challenge is the inapplicability or lack of some operationalizations for some country-specific characteristics. Qualitative assessments based on expert or practitioners’ views can be important to generate insights into the nature and the mechanisms underlying interactions to be included in modelling64.

Timing

Monitoring information needs to be timely to be effective65. Timeliness refers to the availability of monitoring information at crucial points in decision-making processes and the associated debates that may emerge around them. Although in theory, monitoring data could be compiled ad hoc, efficient monitoring systems build on regular data processing. The adjustable main variable is thus the frequency of monitoring. By adjusting the frequency, relevant updated information can be made available at critical points for policy development.

Durability of the monitoring system

While monitoring has at times been portrayed as a rather technical exercise, it requires monetary and political resources and sustained support to endure. This is because first, monitoring is a resource-intensive activity, involving data and information collection, collation, checking and reporting66. This means that, as an administrative exercise, policy monitoring must compete for resources that could also be used for other aspects of policymaking, such as delivery of services or providing subsidies. Therefore, the benefits of policy monitoring need to be clear to administrative, political, and societal actors so that they remain willing to provide support for the activity over the short and long term.

To perceive and understand policy developments over longer time periods, monitoring systems need to deliver information on an agreed set of variables to capture changes in longer-term policy trajectories. By the same token, some gradual adjustments of policy monitoring may be necessary, reflecting new knowledge, technological advances and/or shifting political and institutional circumstances that create a need for new types of information. For example, the sustainable development goals (SDGs) have created a need to monitor the affordability of energy and housing (SDG 7 and 11) beyond emissions. Getting the durability-flexibility dialectic right is one of the key challenges of successful policy monitoring systems.

Justifying monitoring politically

The political nature of monitoring, reporting, and related evaluation exercises has long been a well-known feature67,68,69. Monitoring systems originate in politico-administrative systems, and operate within them. This means that they require some basic level of sustained political and institutional support to maintain legitimacy and the associated and necessary resource flows66. Given that the value of policy monitoring plays out over longer time periods when broader trends in policy development and associated effects become visible, monitoring and reporting exercises may suffer from the vagaries of day-to-day political struggles. Therefore, it is important that monitoring and reporting institutions are sheltered from undue political influence, which could arise if political interests are allowed to determine the level of monitoring funding, methodologies or even results. To establish and maintain long-term monitoring and reporting, the activities need to be perceived as useful, and therefore justify the investment of resources that are required. This is challenging because negative signals from monitoring may also impinge on political interests. The likelihood of support corresponds with the extent to which monitoring outputs can demonstrably assist policy development and enable different forms of learning and subsequent improvements70.

Assessing the monitoring systems at the UN, the EU, Finland and Germany

We use document analysis, including legislation related to policy monitoring, as well as official written reports that monitoring systems produce40,42. Our analysis also includes primary data emerging from the EU’s monitoring mechanism under the Energy Union Governance regulation to understand reporting in Finland and Germany35. Taken together, these sources allow us to assess how these four jurisdictions and governance levels monitor their policy mixes with a view to buildings. While these documents and data are publicly available and work with them therefore a transparent research strategy, they may eschew political conflicts and tensions that emerged in their production. Future research could therefore use additional methods, such as key informant interviews, to explore additional aspects which may not be gleaned from official, published documents.

Responses