Divergence over solutions to adapt or transform Australia’s Great Barrier Reef

Introduction

Crises, including extreme ecological and climatic events, can potentially act as a window of opportunity for transformative policy solutions1. As growing climate-driven events pose additional threats, analysts have theorised that such crises shift perspectives on climate change and create more political pressure for transformative responses2,3. Such transformative responses can include policies that seek to radically alter the status-quo, such as emissions reduction policies that promote low carbon energy and destabilise fossil fuel regimes4,5. However, the challenge remains that stakeholders, policymakers, and the public often have divergent frames, discourses, risk perceptions, beliefs, and interests influencing their opinions about what needs to be done (if anything)6,7. Indeed, crises have also been found to yield a range of policy responses that may be undesirable, including stability and non-transformative solutions8,9.

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef (herein GBR) is a case in point. Coral reefs are some of the most susceptible ecosystems to climate change, with a projected catastrophic 70–90% decline globally at 1.5 °C of heating and over 99% decline at 2 °C, as global temperatures continue to rise10. The GBR is the largest reef in the world and has experienced multiple mass bleaching events, increasing in frequency and severity in recent years11. In the aftermath of the 2016 mass coral bleaching, a convergence of stakeholder views that climate change is the biggest threat to the GBR finally emerged12,13,14. However, while a convergence of views among different stakeholders reduces contention about the problem of climate change and is therefore welcomed by reef managers and climate scientists alike, little is known about whether this convergence shapes the way forward—namely how it shapes perspectives on solutions needed to protect the climate-impacted GBR. And specifically, whether these crisis events might create potential for more transformative solutions.

Transformation and transitions towards sustainability are also now widely discussed in the scientific community and in policy circles, particularly in relation to the climate crisis15. Emerging from resilience theory16,17 transformation refers to a ‘fundamental shift in human and environmental interactions and feedbacks’18. Sustainability transitions are societal-level responses to complex, systemic environmental problems and represent more sustainable modes of production and consumption of natural resources19,20. However, transformations and transitions are still contested concepts, with a diversity of interpretations—for example, in economics, the transformation literature has been critiqued for focusing only on economic change, without social justice considerations21. There is also limited empirical understanding of how transitions and transformations are conceptualised outside of academia.

Improving understanding of actor perspectives on transformative solutions is important for several reasons. Better understanding can aid in the design, implementation, and prioritisation of actions in the context of complex systems change and multiple threats22. Nuanced understanding of stakeholder perspectives is particularly useful when designing policy tools and governance arrangements that require legitimacy and buy-in from a wide range of stakeholders23,24. Perspectives on solutions also may be indicative of social acceptance—a co-determinant of policy performance25. Finally, knowledge brokers can use this information to identify potential future conflicts or areas of consensus, which may assist in the navigation of messy science-policy interfaces26,27.

Despite the clear need for more transformative solutions, unclear actor perspectives on climate problems and their solutions continue to pose multiple challenges for policymakers10,28. Wanzenböck et al.29 and McHugh et al.7 show that both problems and solutions can have dimensions of ‘wickedness’: contestation, complexity, and uncertainty, each which can range from high to low and produce different policy outcomes (Fig. 1). Wicked problems can be contested due to differing perspectives, complexity, and uncertainty from knowledge gaps30,31,32. Solutions face similar challenges, with debates over their effectiveness, feasibility, and potential impacts. The problem-solution space concept was designed to identify specific governance processes to better enable governance leaders to navigate wicked problems toward sustainable solutions (Fig. 1). In agriculture, for example, different values, problem definitions, and complex global networks and players have hampered a global shift to sustainable agriculture (Fig. 1a)29. However, while a ‘problem-solution’ diagnostic has been usefully applied to established policy areas such as agriculture, health, security, and energy, it has not yet been applied to the emerging problem of governing climate-impacted ecosystems. We therefore utilised a problem-solution space diagnostic here to generate insights into how GBR governance leaders might effectively navigate toward solutions.

Bullseye charts illustrate the three dimensions of wickedness in four configurations based on convergence and divergence of the problem-solution space. In quadrant (a) disorientation, both the problem and solution spaces have high divergence indicating there are high levels of wickedness. In quadrant (b) problem in search for a solution, the problem has more convergence, however, there is divergence in the solution space. In quadrant (c) solution in search for a problem, the problem space has high divergence, however, there is more convergence in the solution space. Finally in quadrant (d) alignment, the problem and solution spaces have convergence and low levels of wickedness. Figure adapted from Wanzenböck et al.29 and McHugh et al.7.

To understand different actor perspectives on climate solutions, we first adapted and applied the ‘problem-solution space’ framework drawing on Wanzenböck et al.29 and McHugh et al. (Fig. 1) to characterise the ‘problem-solution space’ of the GBR and identify appropriate governance strategies to address varying problem framings, institutional complexity, and solution contestation. We then interviewed a sample of 34 ‘engaged actors’, purposively selected to reflect a diversity of viewpoints. We defined ‘engaged actors’ as actors with an interest or engaged role in the governance of the GBR, across industry, government, community, non-profit, and science sectors, as well as local, regional, national and international scales. Semi-structured interviews were conducted between June 2021 and March 2022. We started with the open-ended question, ‘What are the main issues facing the Reef?’, for which we conducted a simple inductive thematic analysis. For the second component of the intervew, we used Q methodology to understand areas of convergence and divergence over climate solutions for the GBR. The question was: ‘What interventions to protect the Reef do you support?’. Participants were asked to rank the statements from most to least support within the Q-sort columns. Q method was designed to understand people’s subjective values, beliefs, or viewpoints33 using a quantitative analysis of participant Q-sorts to guide qualitative interpretation. Rather than asking about perspectives on discrete climate solutions, the Q method allowed us explore how participants view all climate solutions in relation to each other. Our reasoning was that policy preferences do not exist in a vacuum but are prioritised relative to alternative solutions. The results enabled deeper understanding of how different perspectives on adaptation and transformation interact to shape the policymaking context when navigating climate solutions for the GBR.

This paper proceeds as follows. First, we explain how crises are creating windows of opportunity for transformative change through shifts in threat perceptions. We then use the problem-solution framework drawn from the wicked problems literature, applying Q-method to understand actor perspectives on transformative solutions. We conclude with a discussion of climate transitions and transformation, and recommendations on how policymakers can best navigate this wicked terrain.

Results

Background to the results

Despite the current gap in knowledge about future change under climate change scenarios, the GBR has in fact undergone continuous, and some argue, transformative change since the 1970s when modern conservation management was introduced. These phase shifts have reflected the evolution of governance and management of the GBR to meet perceived threats and improve social processes for better outcomes11,34. Major shifts include the 2004 re-zoning to increase no-fish zones from 5% to 33% of the GBR Marine Park. Another critical shift involved the increased focus on water quality in adjacent agriculture and mining catchments in the Reef Water Quality Protection Plan35. More recently, the emergence of mass coral bleaching events, with previously unseen frequency and severity from 2016 onwards (2016, 2017, 2020, 2022, 2024), has triggered an expansion of new climate-focused solutions35,36,37.

Recent studies show that mass coral bleaching events have shifted stakeholder and public perceptions of climate change as the main threat to the Reef compared to other threats. A study by Thiault et al.14 surveyed groups before and after the 2016 mass coral bleaching event. Before coral bleaching, threat perceptions varied across three stakeholder groups (tourism, commercial fishers, coastal residents) each identifying different issues as the most threatening (water quality, coastal development, shipping). After the 2016 coral bleaching, all three stakeholder groups converged on identifying climate change as the most serious threat. Similarly, Curnock et al.12 found a shift in risk perceptions of tourists before mass bleaching in 2016 and afterwards in 2017 converging around climate change as the biggest threat. Further studies confirm this shift, including a representative sample of the Australian public and tourists, and a selection of GBR governance decision-makers38,39. Consequentially, there has been even more investment in a range of solutions to protect the climate-impacted GBR. More frequent coral bleaching events have also recently triggered new government investment in restoration and adaptation of corals, and increased community engagement and not-for-profit activity40,41.

The mass coral bleaching crisis on the GBR has thus clearly led to a re-evaluation of threats and their causes and effects. New threat perceptions have also created political pressure and opportunities for action, known as ‘policy windows’, causing shifts in policy subsystems42,43. However, while these recent empirical studies confirm that engaged GBR actors now agree about the wicked problem of climate change for the GBR, they highlight that little is known about how these diverse actors perceive the solutions.

Convergence over the problem but divergence over the solutions

In the first open-ended question, every participant identified climate change as the main issue facing the GBR. This result confirms converging views that climate change is now perceived to be the biggest threat to the GBR, as described above12,13,22. However, the following Q-sort revealed six distinct perspectives on solutions. The six perspectives on solutions ranged from ‘coral adaptation and technology solutions’ to ‘integrated resource governance solutions’, ‘ecosystem health solutions’, ‘market-led climate transition solutions’, ‘regionally-led climate transition solutions’ and ‘radical climate transition solutions’ (Table 1).

Key sectoral alignments and divergences over solutions

Three of the six perspectives prioritised climate mitigation solutions relating to climate transitions, with variation on the preferred mix of solutions to support these transitions (radical climate transition solutions, regionally-led climate transition solutions, market-led climate transition) (Table 1). Notable divergences occurred between the positions of science and industry—with 25% of industry and 0% of scientists holding the coral adaptation and technology solutions perspective, and conversely, 80% of scientists and 0% of industry holding the radical climate transition solutions perspective (Table 2). For government, 43% aligned with regionally-led climate transition solutions; 28% with integrated resource governance solutions; and 14% with radical climate transition solutions. NGO perspectives were concentrated on radical climate transition solutions (43%), with the remaining participants spread across most perspectives (8% for market-led climate transition solutions, ecosystem health action solutions, integrated resource governance solutions, and coral adaptation and technology solutions). Notably, no NGO participant aligned with the regionally-led climate transition perspective.

Most and least supported solutions

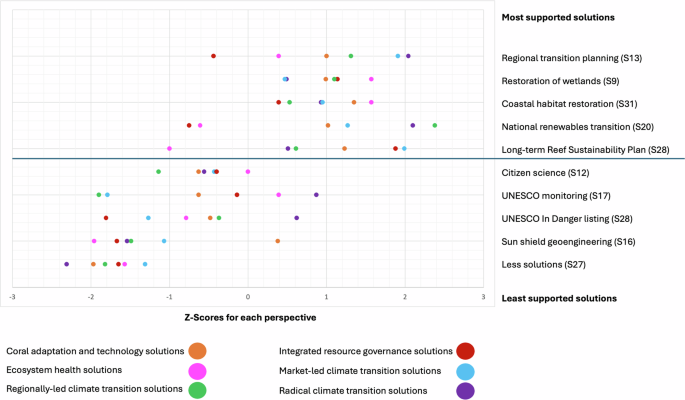

Of specific solution statements, the most supported were two climate mitigation solutions, two ecosystem restoration solutions, and one planning solution (Fig. 2). When all perspectives were combined, the top five most supported solutions exhibited higher levels of consensus overall (z-score > 0.80) than the bottom five least supported (z-score < −0.50). However, there was more consensus around the two least desirable solution statements (z-score < −1.20). The statements with the least support were ‘less solutions’, indicating a preference for more interventions to protect the GBR; and, sun shield geoengineering, indicating strong aversion or scepticism to some technological solutions. For climate mitigation solutions, regional transition planning and national transition to reduce emissions were most supported, with carbon markets and personal reduction of carbon footprint within an average range but showing division between perspectives.

Most and least supported solutions are listed, with corresponding Z-scores for each perspective. Z-scores above +1 and below −1 are most indicative of support or lack of support from each perspective.

Discussion

Wicked problems, such as climate change, are characterised by contestation, complexity, and uncertainty30,44. Traditional technocratic approaches are insufficient in solving wicked problems, because people and organisations may not even agree on the nature of the problem due to different values, institutional logics and messy trade-offs31. Instead, policymakers must identify suitable governance processes through all stages of the problem to support development of coherent policy solutions among multiple stakeholders32,45,46.

In building legitimacy and cooperation among various actors, engagement processes need to be tailored to the specific characteristics of each wicked problem and its solution32. Problems, for example, can be contested due to multiple framings, polarised stakeholder views, and normativity. Problems can also have various degrees of institutional and situational complexity, as well as uncertainty due to knowledge gaps around cause and effect. Solutions, by contrast, can involve contestation over which solution is the best. Complexity occurs when solutions need to have systemic impacts, and uncertainty can exist over effectiveness, feasibility, and undesirable impacts. The failure to reduce dimensions of wickedness in the problem-solution space can result in an intractable problem persisting, and inability to develop and implement viable solutions. It is therefore necessary to effectively diagnose wickedness through highlighting different configurations that can occur when problem-solution spaces do or do not align.

Our aim was to discover whether convergence over climate change had resulted in convergence of perspectives over solutions to protect the GBR. Our results showed a variety of perspectives on solutions, including one prioritising new adaptive approaches (coral adaptation and technology); two in support of conventional conservation approaches (integrated governance and ecosystem health); and three perspectives that prioritised new climate transitions (a market-led climate transition, a regionally-led climate transition, and a radical climate transition). Thus, the results confirm that the crisis of increasingly frequent and severe mass coral bleaching events has not yielded convergence over solutions. Furthermore, they confirm that actor divergence over solutions implicates not only formal decision-makers, but a broad range of actors involved across sectors and scales of GBR governance47. However, we note our findings reflect our sample.

We also aimed to understand whether the climate crisis may create more support for transformative change (more systemic, deeper social, economic change) as a means to protect climate-impacted ecosystems, and how actors conceptualise these transitions and transformations.

We found that each climate transition perspective differed in the preferred type, the degree of social and economic change, and the actors involved. The most transformative perspective highlighted by engaged actors was the radical climate transition perspective, which emphasised a high degree of social and economic change. The radical climate transition perspective prioritised Indigenous involvement, reflecting broader global discourse on just transitions coupling large-scale economic change with social justice dimensions48. The radical climate transition solutions perspective was thus the most transformative perspective of the whole set, linking fundamental social, economic, and ecological change. Participants adhering to this view often critiqued capitalism, colonialism, and fossil fuel industries, seeing them as structures that needed to be changed to enable both social and ecological sustainability. Unsurprisingly, this view was most supported by scientists and NGOs, with no participants from industry supporting this perspective. The result confirms that many industries oppose radical approaches to transformative change13,34.

Interestingly, we also found support for a regionally-led climate transition, a perspective that may indicate growing support for a transition that is more place-based, where subsidiarity of decision-making and action are prioritised49. Within this regionally focused climate transition, the role of NGOs and UNESCO were least supported. Those most aligned with this perspective were from government and industry. Finally, the market-led climate transition perspective prioritised markets and economic incentives to drive solutions, with participants favouring these approaches as less divisive than regulation, particularly in relation to farmer behavioural change. Industry was most aligned with this perspective, alongside NGOs. This preference for a market-led perspective echoes preferences in other environmental governance settings50 suggesting the market-led perspective spans contexts. What is perhaps most noteworthy from these climate transition perspectives is the emergence of the ‘market-led’ and ‘regionally-led’ climate solutions, because they indicate increased appetite for transformative policy from typically more conventional actors such as industry and government. Furthermore, the emergence of three types of climate transition perspectives indicate that transformative change may not be opposed if the specific interventions used to guide climate transitions are accepted by particular sectors. Indeed, research into low carbon transitions is increasingly focused on how transitional assistance policies and strategies can be used to implement transitions in a way that is politically acceptable, equitable, and just towards affected sectors, regions and workers51,52,53,54,55.

Our final aim was to understand the overall problem-solution space of the GBR to draw governance insight into how solutions can best be navigated. Our analysis builds on contemporary understandings of wicked problems, in particular the idea that not all wicked problems are in a black box, rather they exhibit dimensions which, when understood, can be used to discern what kind of actions would be best suited in navigating solutions. In applying the dimensions of wickedness drawn from the problem-solution space framework29—contestation, complexity, and uncertainty—we found the GBR problem space had low contestation, high complexity and low to medium uncertainty (Table 3). For the GBR solution space, however, we found medium contestation, high complexity and medium to high uncertainty. Therefore, overall, we characterise the problem space as somewhat more convergent than the solution space (Fig. 3). However, in both spaces, the complexity dimension of wickedness remains high.

Radar chart shows three rings—the low score in the centre of the chart, the medium score represented by the ring in the middle, and the high score represented by the outer ring. Each line from the centre represents one dimension of wickedness—contestation, complexity, and uncertainty. The scores for the problem space are represented by the colour purple and the scores for the solution space are represented by the colour blue.

In summary, our analysis shows that the climate-impacted GBR is still very much a problem in search of a solution (Fig. 1b). The problem dimensions are now relatively converged, but there is divergence over how to choose and implement effective solutions.

Drawing on contemporary understandings of governing wicked problems29,56 our results suggest solution convergence may be achieved through stronger efforts at social learning and reflexive governance. Social learning involves gaining knowledge and improving relationships through social interactions. It can be also achieved through cognitive learning, which involves collective knowledge transfer, and relational learning, which involves learning through relationships with others. Deliberative governance processes, like stakeholder engagement, can support social learning and cooperation. Reflexive governance then focuses on adapting and changing governance structures and rules to improve effectiveness in complex and diverse contexts57. Reflexivity involves considering the perspectives, values, and norms of various actors58. Reflexive governance thus complements social learning by emphasising the need for inclusive and responsive governance to address climate action challenges59,60,61.

Considering the importance of social learning and reflexivity, and the emergence of climate transitions as an organising concept for GBR solutions, the opportunity is ripe for a new climate change-focused venue for the wider GBR region and its catchment. Such a venue could be envisaged as a multi-stakeholder platform or authority that facilitates collaborative processes for decision-making on climate change. Existing collaborative governance initiatives for the GBR, such as Local Marine Advisory Committees (voluntary community-based committees for stakeholder discussion and input for marine park management) and the Reef 2050 Long-Term Sustainability Plan, can serve as examples62. However, a collaborative governance initiative more specific to climate transitions in the wider GBR region could engage a broader network of stakeholders, improve social acceptance for change, and enhance capacity for social learning53.

Indeed, transition management is an emerging governance approach that can accelerate sustainability through collaborative visioning, learning, and experimentation63,64. Collaborative governance initiatives could take the form of a multi-governmental institution involving national, state, and local governments, labour unions, businesses, and communities. Such an institution could focus on enhancing regional transformation capacities by steering investment, advocacy, and influence, fostering cross-sector alliances, and addressing climate impacts on industries, conservation, and sustainable development. Such institutions also emphasise the need for national and subnational policy support to build local transformation capacities65. Transition authorities and programmes have already been used to govern, support and re-direct social and economic change, after closure of fossil fuel industries in Australia and internationally66,67,68. Indeed, thinktanks are now beginning to outline how the GBR region could benefit from a similar governance model to proactively coordinate and plan for renewable energy transitions69. This concept could be extended to address climate change resilience of the region more broadly through the establishment of a regional climate transition authority. Transition management can thus be tailored to consider socio-political contexts, potentially employing incentive-based strategies to engage industry, local leaders and major political parties. Using strategic framing can also help avoid the politicisation of climate change terminology, in a similar fashion to how national climate policies in the US have been reframed to address inflation concerns70.

Such a governance opportunity is not only relevant to the GBR, but to climate-impacted ecosystems globally. In designing such venues, governance leaders should focus on areas where collaboration can bring added value and enable new relationships, decisions, and changes that would not be otherwise possible71. Our recommendations also align with broader civic and policy ambitions across contemporary democracies, such as inclusivity and effectiveness72. Future studies should be directed toward enabling the co-produced design and implementation of these potentially transformative governance models.

Methods

We sought to understand whether increasing convergence over climate change as the main threat facing the GBR was leading to convergence over solutions, and whether perspectives on solutions were transformative. We asked: Does convergence of perceptions of climate change threat to the GBR lead to convergence over perspectives of solutions? Are extreme climate events shifting perspectives towards transformative solutions to protect ecosystems? And, finally, given climate change is recognised as a wicked problem, how might reef leaders and policymakers best navigate this space for the most effective outcome?

Developed in the 1930s, Q method was designed to understand people’s subjective values, beliefs, or viewpoints33. Although not as widely known as R methodology, Q method has been widely applied across the social sciences, including health, psychology, management, economics and environmental sciences73. Within the environment and sustainability fields, it has proven to be a useful method through which to explore stakeholder viewpoints of environmental problems and solutions25,74,75,76,77. Q method is advantageous in this regard because it ‘can uncover perspectives or positions in a debate, without imposing predefined categories’78, yet maintains replicability with only limited interpretive input from the researcher. Q method differs from R methodology in that does not seek to represent an ‘objective’ relationship, (i.e. to understand the level of support in the population for a proposition) such as in surveys. Rather, Q method has a post-positivist philosophical grounding, whereby concepts are defined within and across individuals, uniquely reflecting collective alignment around particular patterns of thinking (i.e. to understand the variety of perspectives in a population). Q method elicits dominant perspectives emergent from clusters of participants who share similar patterns of perspectives. Due to this approach, valid results can be produced with only a small number of participants (typically 10–30) with purposive selection of participants aimed to reflect the range of views on a topic. The assumption of ‘finite diversity’ supports this approach, as there are usually fewer common viewpoints than participants79. Ultimately, the aim of Q method is to determine what is different about the dimensions of subjective phenomena and to identify characteristics of common viewpoints shared between individuals80.

Another benefit of the Q approach is that rather than asking about perspectives on discrete aspects of a subject, the analyst can also explore how participants view all aspects of a subject in relation to each other—the completed Q-sort ‘whole’ is thus different to judging each of the parts individually. We therefore chose Q method for understanding perspectives because a Q analysis can reveal not only what solutions are supported but also how they are supported in relation to one another. Our reasoning was that policy preferences do not exist in a vacuum but must be judged in the context of what is available or what other solutions could be better.

For a Q study, there are four phases of data collection and analysis81, as discussed below:

-

1.

Statement drafting and selection

First, a Q sample is developed by reviewing the ‘concourse’, or the discourses around a topic. We developed the concourse by reviewing 50 statements of solutions to protect the GBR from the websites and reports of NGOs, industry representative organisations, government agencies, and natural resource managers. We also reviewed international, national, and regional media reporting on the GBR and scientific research articles to capture multiple viewpoints and key debates. We then organised the statements to reflect different dimensions of the solution space. We used a structured matrix with the following dimensions to guide selection: issue, scale, sector, approach, innovation, knowledge, and instrument (Table 4). We simplified the statements but where possible retained their original expression, so the statements best represent how discourse is communicated by different actors on websites, in the media, or in reports on the issue (Table 5). The aim of the statement selection was to ensure all dimensions were represented, enabling participants a wide variety of solutions to select from, and to reduce researcher bias towards selecting specific solution types.

Table 4 Different dimensions of solutions proposed for the Great Barrier Reef Table 5 Range of solutions to protect the climate-impacted Great Barrier Reef -

2.

Interviews with a purposive sample of participants

Interviewee sampling strategy was purposive, as we sought to represent the diverse perspectives of ‘engaged actors’ who we defined as actors engaged in GBR governance through specialised knowledge, livelihood, professional interest, or governance participation. We aimed to reflect the polycentric governance of the GBR by diversifying our selection across multiple scales to include local, regional, national and international actors, aiming for at least one participant from each scale where possible. We also selected participants across relevant sectors (science, industry, community/NGO, government) (Table 6). With this approach we were able to capture a wide range of perspectives. The proposed research received human ethics approval from the James Cook University Human Research Ethics Committee Approval Number H7848. Informed consent verbally and/or on a consent form prior to all interviews.

Table 6 Examples of engaged actors interviewed Participants were recruited through professional networks, forums, snowballing and cold emailing. GBR forums included community networks (Local Marine Advisory Committees) and a GBR symposium where diverse stakeholders were in attendance. Examples of our participant affiliations included: international intergovernmental organisations: International Union for the Conservation of Nature (n = 1); Federal, State and Local governments and agencies (n = 7; e.g. the GBR Marine Park Authority; the former Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment; the Office of the GBR; the Queensland Department of Environment and Science); local, national, and international advocacy NGOs, community groups and natural resource management organisations (n = 11; e.g. the GBR Foundation; the World Wildlife Fund for Nature; Local Marine Advisory Committees); research Institutions with leading scientists from diverse disciplinary backgrounds across climate change, coral reefs, regional governance, tourism, marine engineering (n = 6; e.g. James Cook University; Commonwealth Science and Industry Research Organisation; the Cairns Institute); and industry representative organisations and businesses from agriculture, mining and infrastructure development, and tourism (n = 9; e.g. the Queensland Resources Council; the Queensland Farmers Association; Townsville Enterprise). It is important to note here that the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) was approached to participate but declined, and human ethics approvals did not permit specific targeting of Indigenous groups in this study.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in person or over video call, between June 2021 and March 2022, typically lasting 60 mins. We started with an open-ended question, ‘What are the main issues facing the Reef?’, for which we conducted a simple inductive thematic analysis to understand the prevalence of climate change being mentioned as the main issue by participants. The second question was then: ‘What interventions to protect the Reef do you support?’. Participants were asked to rank the statements from most to least support within the Q-sort columns and were encouraged to verbalise their views on the statements as they sorted them. After the Q-sort was completed, participants were asked to elaborate on why they selected particular interventions as their most supported and least supported, to ensure depth to the qualitative responses. The recorded interviews were then transcribed.

-

3.

Factors generated through quantitative statistical analysis

Through interviews we collected 34 Q-sorts, reflecting how participants had ordered their solution statements across a normal distribution pattern of slots. Based on the prioritisation of solutions, we generated factors (which are the statistical representation of a perspective). Data analysis included correlation and by-person factor analysis (statistical analysis is by person, rather than by statement, trait or other variable). Our Q-sort data were analysed using Ken-Q software. Analysis consisted of: (1) Pearson correlation coefficient; (2) Factor extraction: Principal Component Analysis (8 extracted principal components); (3) Factor rotation: Varimax (selected 6 factors for rotation). To identify participants who aligned with each factor, autoflagging was set to p < 0.05, indicating a statistically significant relationship. The six factors which explained the highest variance of the results (highest factor 35% to lowest factor 5%), with 70% cumulative variance explained were selected as the results. Two factors were excluded because they explained >5% of cumulative variance and had Eigenvalues of 1.5 or below. In Q method, factor selection is up to the researcher’s discretion, as all factors may not have the same explanatory value of perspective range (diversity). For our determination we used standard criteria to guide the number of factors extracted: those reflecting higher total variability explained, explanatory power and parsimony25,82.

-

4.

Factors used to guide qualitative description

Once the six factors were determined, we used factor scores to guide qualitative interpretation and description78. For each factor, we analysed the participants most aligned with the factor, and grouped verbal responses corresponding with the statements that received the highest and lowest scores (top and bottom 5), which are the most important in characterisation of a Q factor. The lead researcher then wrote descriptive summaries based on the overall factor score, the participant verbal responses to the highest and lowest scored statements, referring to the remaining qualitative data for more clarity when needed. Following this, a second researcher reviewed the summaries alongside the participant responses, to check fairness of interpretation.

Research note on statement selection

In Q method, we as researchers aim to maintain the common language used in the wider concourse, rather than developing our own terminology and definitions83 (Brown73). This is both a limitation and strength of the statement selection in Q method. Statements themselves may be not be agreed upon by all, but similarly this often reflects differences in the discourse over an issue.

For example, for statement 16 we chose the term ‘sun shield’ and description ‘biodegradable surface films on the ocean to reflect heat’ from a description used on the website of The GBR Foundation, a charity who has invested in the technology. We chose the term ‘geoengineering’ to indicate this statement as representative of geoengineering as a type of solar radiation management innovations. The term ‘geoengineering’ comes from the Australian Commonwealth Government where solar radiation techniques to either reduce the amount of incoming solar radiation, or increase the amount reflected are included84. However, geoengineering is typically considered unpopular with the public, so the term ‘geoengineering’ may have elicited a response that would have been more negative than if another statement of the same intervention was used85. For our study, is remains useful to understand perspectives on geoengineering (including the terminology) as long as these limitations are considered.

During interviews, participants who asked the researcher for more information about a solution statement were given the source from where the statement was drawn as contextual information. For example, for the statement ‘Market-based Reef credits scheme where farmers/landholders can earn income through actions to reduce run off’, the researcher described it as a new initiative from the Queensland Government. Beyond this, there was no more contextual information given to reduce researcher influence. Generally, the statements held enough clarity for participants to pass judgement over them.

Research note on interview script for Q-sort activity

Script notes:

This is about interventions to protect the reef—I’d like you to sort them from ones you support the most to ones you support the least. You can see there are a smaller amount of boxes for the cards at each end and more in the middle—this is a bell shaped curve and allows me to make statistical comparisons. You can either look through the cards first or just start moving and sorting them. If you have any questions or don’t understand something on the cards please ask. And if possible can you talk me through what you’re doing, because I’m interested in why you are placing the cards in a particular position. What interventions to protect the GBR do you support the most? Please rank from most support to least support.

Follow-up questions:

Which interventions do you most support and why? Which interventions do you least support and why?

Responses