Failed mobility transition in an ideal setting and implications for building a green city

Introduction

The transport sector is one of the biggest drivers of the climate crisis worldwide1. To mitigate the climate crisis and its life-threatening risks, mobility must be transformed. Cities play a central role2,3,4,5, because they develop and implement mobility concepts and shape the transition. The German City of Tübingen offered the ideal setting for a successful mobility transition for several reasons: It is a green university town with a green mayor and green municipal council, many people vote for the Green Party and have done so for decades, academics on cargo bicycles cruise through the old town alongside many buses. Tübingen is known throughout Germany as a green model city6,7 and is always at the forefront of climate protection. Tübingen is the ideal place to push ahead with the mobility-transition and the ideal place for a tramway to make individual transport superfluous. However, despite an apparently optimal setting, the mobility transition failed. Tübingen planned a tramway as part of the large-scale project “Regional Stadtbahn Neckar-Alb”, which is to connect Tübingen’s surrounding area and has been under construction since 20198. In September 2021, the majority of Tübingen’s citizens voted against this tramway in a referendum. In addition, all relevant actors were in favour of the tramway including environmental groups, which had no environmental concerns, the tram was part of Tübingen’s climate action plan9 and funding was secured10. This requires a great deal of explanation. Why was the tramway still rejected, and what can we learn from this missed opportunity for future projects?

The climate crisis and the solutions for it are often seen as technical problems for which technical solutions are needed. Since Tübingen offered an ideal setting and still failed, this case-study shifts the focus: Mobility transition is not seen as technical endeavour, but as an often side-lined discourse-communicative challenge acknowledging the importance of socially embedded narratives. Little is known about which factors influence such opinion-forming processes, how acceptance is created11,12 and how discursive negotiation processes can be successfully shaped in transformation processes such as the mobility-transition at the local level. Through a discourse network analysis (DNA) on Tübingen’s tramway, we collected data to further examine the communication of future urban mobility-transition projects and discursive pitfalls on the way to sustainability. The aim of this study is to explain the negative outcome of the referendum in Tübingen. In this context, we raised three sub-questions:

-

1.

Which actors and frames shaped the discourse and how did it develop?

-

2.

To what extent was the tramway negotiated within the nexus of the mobility-transition?

-

3.

To what extent were the opponents of the tramway more convincing in the discourse?

The aim of the DNA is threefold: First, we analyse the associated discourses, identifying argumentation patterns, discourse dynamics and coalitions. Second, we analyse argumentative strengths and weaknesses in relation to current research. Third, these insights of discursive pitfalls might provide support for the success of future local mobility-transition projects.

We combine the DNA with a specially developed narrative analysis grid to cast an innovative perspective on this local political opinion-forming process. Our normative basis is that the rejection of the tramway represents a failure for the mobility-transition, as the tramway would have offered a convincing alternative to individual transport and can offer many advantages regarding low emissions and comfort. A report on the traffic impact in Tübingen of a tramway and an assessment of alternatives such as buses and cable cars also concluded that the tram has the greatest impact on traffic, as more commuters will use it instead of their car, among other things10,13. We argue that the pro-discourse coalition squandered the opportunity and could not use the ideal starting position to support the project. Instead, it provided unintended support for the counter-protest in the form of discursive weaknesses, disastrous communication flaws and inadequate consideration of the socio-technical issues. The contra-discourse coalition used a clever mix of NIMBY and sustainability arguments embedded in more connectable mobility narratives and thus gained high discursive power. From a discursive-communicative perspective, the rejection of the tram can thus be explained.

Sustainable mobility is understood as mobility that meets human needs, creates social justice and preserves ecological limits14,15. It can be achieved in the hierarchised interplay of less, different, and more efficient mobility. Sufficiency plays a crucial role, as the switch to electromobility is not enough16.

Since infrastructure and climate protection projects in the transport and energy sector are often seen as technical problems and met with protest11,17,18,19, it is essential to see Tübingen’s tramway as a social problem and thereby focus on the associated discourses and narratives. Planning processes such as mobility measures are “technical endeavour” and “rhetorical activity”20. Discourses produce meaning, reflect, and generate social realities and practices. Additionally, they legitimise hierarchies, construct and structure reality and determine what can be said and done. By this, they produce narratives to convince others21,22. Discourses emerge through verbal interaction between actors on mutually dependent normative statements and are a “dynamic network phenomenon”23.

Reviewing the literature in the context of sustainable urban mobility transformation, we find many articles that focus on exploring the transition to sustainable urban mobility from a socio-technical24,25 or economic-oriented view26. Only very few articles address the topic from a political science perspective with a specific focus on discourse and narratives27,28. Theoretically, Kallenbach’s research28 is based on the mobility culture framework and argues that mobility transitions can only be understood if we consider discourses that explain how mobility cultures are influenced. Brömmelstroet et al.27 draw on Holden et al’s mobility narratives29 and add a socio-economical and deliberative process perspective. Our perspective is aligned with a relational and constructivist approach, which necessitates the inclusion of discourse coalitions. This is based on the conviction that relationships between different actors are pivotal to a more nuanced understanding of the social dimensions under examination. Hajer30 developed the concept of discourse coalitions and understands it as a group of actors who share ideas and concepts, frame a political issue, ascribe meaning to it, seek to convince others of ‘their’ reality or impose ‘their’ view on them, and strive for discursive hegemony to translate their ideas into policies30,31. The discourse coalition approach can be used to analyse strategic action, conflict resolution, the assertion of interests and the emergence of a common orientation of actors, without their actions being closely coordinated30. Although Hajer remains methodologically vague32, this approach is valuable: Tübingen’s actors can be conceptualised as competing groups that positioned themselves on the tramway and struggled for discourse hegemony. Moreover, the approach can be linked to narratives and framing. The Advocacy Coalitions Framework33 and the Narrative Policy Framework34, which posit that deep core beliefs are the primary explanatory factor, are similarly unable to account for the decision of the majority of green citizens to vote against the tramway.

Narratives give meaning to ideas, convey complex information, and legitimise political action30,35. Whether it is the emancipation of women, the abolition of slavery or civil liberties, major historical changes and political processes rely on (future) narratives20,29,36. Narratives are, therefore, essential if the mobility-transition should be successful. Frames are subordinated to discourse and narratives37,38. Depending on how one and the same factual situation is framed, people can form different opinions. The more often a frame is perceived, the easier it is to recall and solidify. Conversely: Ideas, values and moral concepts that are not expressed linguistically do not persist, and their political significance and implementability decay38. Framing can be used rhetorically by (political) actors, e.g., in election39 or protest campaigns40. Thus, the transformation towards sustainable mobility requires narratives that politicians, businesses, and citizens can understand and support35,41.

Holden et al.29 developed three grand narratives for a mobility-transition, which we use as an analysis grid to structure the discourse. Those narratives are based on the sustainability strategies of efficiency, alteration, and sufficiency: moving around (a) more efficiently, (b) differently, and (c) less16. (a) The ‘electromobility-narrative’ is about switching from combustion engines to electric motors to achieve low-carbon transport42. (b) The ‘collective-transport-narrative’ includes the expansion of public transport and forms of mobility that propagate sharing/using instead of owning. This makes it not only central in terms of environmentally sustainable mobility, but also ensures basic transport needs, equal access to mobility and greater independence for vulnerable groups. (c) The ‘mobility-reduction-narrative’ proposes less to no vehicle use. It is about efficient public transport and the elimination of private transport. The aim is to create car-free cities with high quality of life. It is about renegotiating what a good, just life is.

While all three narratives are generally credible in terms of feasibility, acceptability and centrality/effectiveness, there are differences as they challenge the status quo to different degrees and have different levels of impact29,36. The ‘electromobility-narrative’ is the most widespread, accepted, and easiest to implement as it has little impact on the status quo42. In contrast, to implement the ‘collective-transport-narrative’ and the ‘mobility-reduction-narrative’, a widely accepted car culture15 must first be broken and changed. Furthermore, the relationship of the three narratives to each other must be considered. A sustainable mobility-transition can only succeed if the three narratives are hierarchised: mobility should be first reduced, second altered and third made more effective. Additionally, if they are told simultaneously as well as seen as both complementary and substitutive, the narratives can mutually reinforce each other positively and negatively. The ‘electromobility-narrative’ is thus most recognised but should not be prioritised16. Less mobility or making it collective is less accepted but should be priority to achieve sustainable mobility. For an optimal mobility transition, these narratives need to be told, believed by the different actors and translated into policies29.

In local protest and negotiation processes, discursive lines of conflict emerge11 between proponents and opponents by recourse to the concept of home43 and along the claim to represent the common good11 in order not to be discredited due to NIMBY-interests40. Personal concern also mobilises44. Lessons from other studies on polarised debates around infrastructure projects are: actors should appear united, communicate openly and, instead of focusing on technical aspects, make the benefits for people central, e.g., through narratives that appeal to heart and mind45. Moreover, it should not be claimed that planning has no alternative. Projects must be legitimised through communication18.

The mobility-transition is a wicked problem that requires technical and social changes15,29,46. The following insights are important to understand the rejection of Tübingen’s tramway: First, mobility-transition must be conceptualised multidimensionally. It is about climate and environmental protection by reducing CO2-emissions and other pollutants, about health protection through reduced air and noise pollution, about more liveable and social cities with a high quality of life and space for people instead of cars, and about counteracting land competition and reducing pressure on the housing market15,42,47. Second, for local politics, the climate crisis must be made a local issue2.

Third, a recent study48 showed that although most Germans are in favour of more traffic avoidance, they are much less in favour of concrete measures. However, the more affected people are by traffic burdens, the more they agree with the mobility-transition. The study concluded that the relieving effects of the measures must be emphasised and that an overall concept is needed48. If the benefits of measures in the context of the mobility transition are highlighted and made clear to people, more acceptance will be created, and barriers will be broken down. Burdens and benefits must not diverge too much, otherwise the NIMBY-phenomenon occurs12,18.

Fourth, current evidence shows that new modes of mobility need to fit the respective city and its mobility culture to be accepted15,49. Different mobility cultures lead to different implications for new forms of mobility. Cities can shape the mobility experience by defining what types of mobility are possible and where, and by linking new forms of mobility to the existing culture.

The rejected tramway in the city of Tübingen (~90,000 inhabitants) was chosen as a case study because it represents a special case as already outlined in the introduction. Moreover, normally, with such infrastructure projects, political actors are strongly divided, and environmental groups are opposed19,50,51. But in Tübingen, political actors across parties and environmental groups were united. The political will was strongly present. Moreover, both pro- and contra-citizen initiatives were founded in Tübingen, and therefore the conflict was not just between city administration and citizens11,52. Also, medium-sized cities have been neglected in research on climate crisis governance3 and protest research has produced little on smaller and local protest and its impact and influence11. Moreover, from a participation theory perspective, much was done right in Tübingen, because of various forms of citizen participation. This shows that being green and participating is not enough—communication, however, is key and is, therefore, the focus of this case study.

The tramway was part of the large-scale project “Regional Stadtbahn Neckar-Alb”, which is supposed to better link the region without transfers8,53. The idea originated in 1994; construction work began in 20198.

The tramway was assigned central importance for the whole project and for climate protection since changing trains at the main station would have been eliminated, and a large part of Tübingen’s jobs are located along the route. Therefore, a large shift from car to rail was predicted by a report which also assessed the traffic impact of different alternatives such as buses. Buses, on the contrary, would be used by fewer people, and fewer car kilometres would be shifted10,13. The university and the hospital are the largest employers. More than 37,000 people commute into Tübingen, almost 19,000 out and almost 47,000 within Tübingen54. The city has city buses (TüBus), regional buses and is accessible by train. Within the city, the majority of Tübingen’s citizens walk (75%) or cycle (61%). Just under half use buses, and only 25% use cars55.

The referendum on the question “Should the tramway be built in Tübingen?” took place on 26. September 2021 at the same time as the federal elections. The voter turnout was 78.37%. The tramway was rejected by 57.39%, while 42.61% voted in favour56. Differences in voting behaviour had been analysed in relation to sex, age, and interest in city affairs55. While for the supporters of the tramway, arguments regarding the facilitation for commuters, the better connection of the clinic, university and technology park, but also climate and environmental protection reasons were decisive55, the opponents had more arguments in terms of numbers, but less support for the individual. Opponents cited the situation in the Mühlstraße (one of the most influenced streets by the tramway), the feared disadvantages for trade, gastronomy and commerce during the construction phase, as well as cost arguments and concern for Tübingen’s historic townscape as important55. The study showed a close correlation between expected benefits and voting behaviour55 and concluded that proponents were not successful in convincing citizens of the benefits of the tramway55. Since the arguments were decisive for the voters55, DNA can provide further information about the motives.

Results

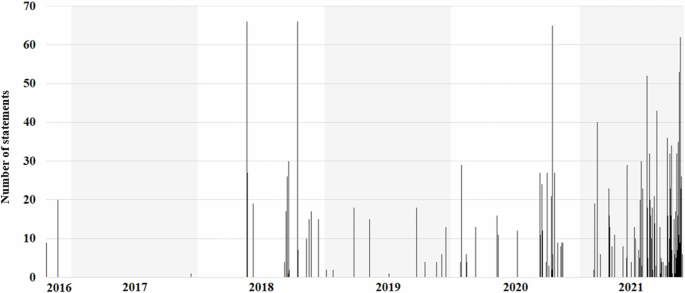

The political opinion-forming process before the tramway-referendum can be interpreted as struggle for discursive hegemony of two discourse coalitions. As shown in Fig. 1, the “Schwäbisches Tagblatt” made the tramway an increasingly frequent and prominent topic over time. Within the 140 coded newspaper articles, 199 frames and 2062 statements were coded by over 150 actors from 51 organisations (Supplementary Table 1 and 2). This high number of frames indicates the socio-technological complexity of the topic30.

This figure shows the occurrence of the newspaper articles that had been selected by using keywords and the number of statements present within the selected articles, as articulated by various actors.

Analysis media discourse

To further refine our analysis, we present different discourse networks, each according to degree centrality with frequencies and link weight.

Actors in the media discourse

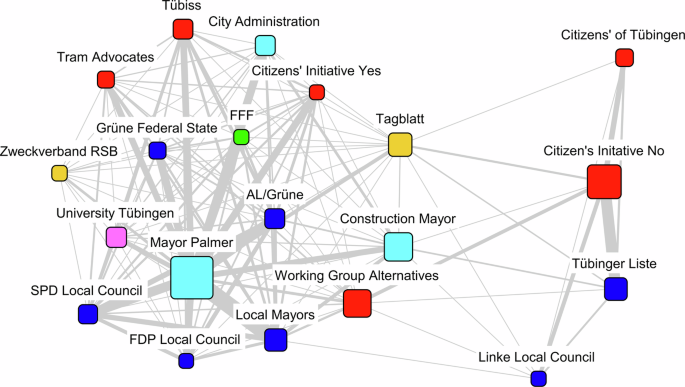

Fig. 2 displays the most important actors in the discourse. The actors’ constellation is polarised, and the two main discourse coalitions—proponents (left) and opponents (right)—are clearly visible. The former has more actors that are more closely linked argumentatively. While the pro-discourse coalition consists of various political actors—Tübingen city administration, environmental/climate groups, associations/clubs/companies, universities, as well as civil society groups—the contra-discourse coalition only has actors from politics and civil society. The main actors and, at the same time, opponents are the mayor Boris Palmer and the citizens’ initiative against the tramway. Both have a key position in the discourse. Although the pro-discourse coalition has a strong presence in the discourse, it cannot take advantage of this and is defeated in the referendum. To what extent there is a media bias in favour of the contra-discourse coalition must remain open: The contra-discourse coalition appears relatively often in the discourse despite its low number of organisations/persons. Besides, the contra actors strongly overlap. It is also interesting to see who is hardly present, such as pro-actors like the citizens’ council (Bürgerrat 2021) or bicycle lobbyists (VCD, ADFC).

This figure illustrates the one-mode actor subtract-network of the 20 most frequent actors in the media discourse. The size of the nodes is indicative of the frequency with which the actor appears in the selected newspaper articles, expressed as a numerical value. The link strength indicates the degree of connection between the nodes (concepts), with stronger connections occurring when the nodes agree on more concepts and vice versa. The colours assigned to the nodes represent the following organisational types: red denotes civil society, light blue signifies city administration, yellow represents associations/companies, dark blue indicates political actors, green denotes environmental groups, and pink denotes universities.

Frames in media discourse

In the following, subtract-networks of concepts are presented. The frames are assigned to the five narratives of the analytical grid (Supplementary Table 1). Tübingen’s tramway was supposed to change the nature of mobility, make individual transport superfluous and the city centre car-free. The frames on the tramway are thus assigned to the ‘collective-transport’ and the ‘mobility-reduction’ narrative. The frames on the (high-speed) bus alternative belong to the ‘electromobility’, and the ‘collective-transport’ narrative, as existing buses are to be replaced by e-buses, and the bus network is to be expanded.

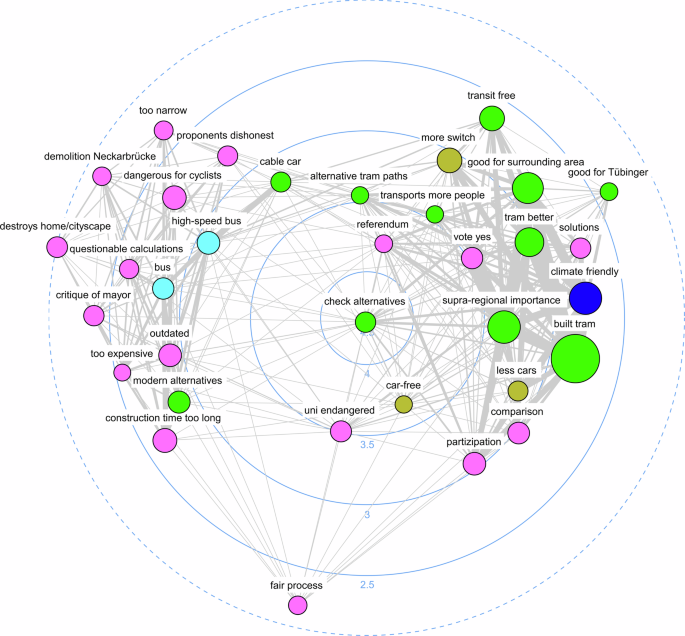

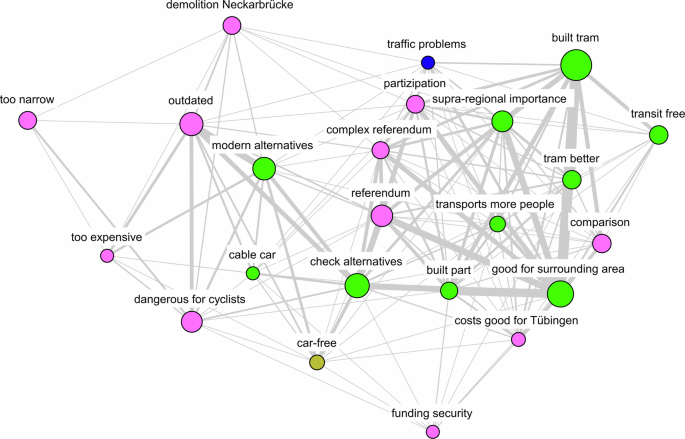

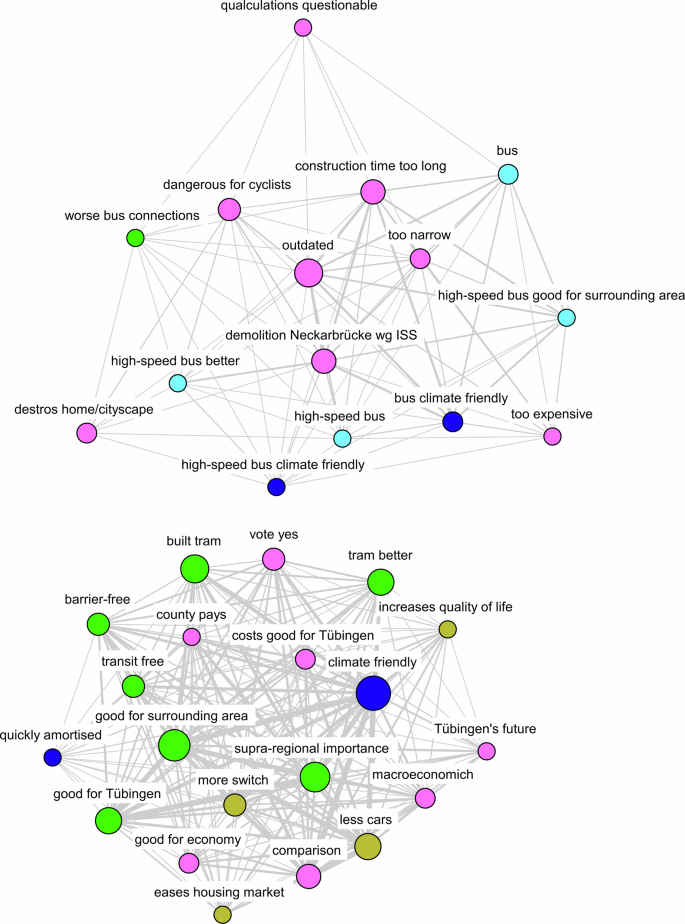

Fig. 3 shows the linking of the frames over the entire period and illustrates how strongly the discourse is polarised. The two discourse coalitions—pro (right), contra (left)—are connected by the frames in the middle (especially ‘check alternatives’), otherwise the network would disintegrate. The further away the arguments are from the centre of the layout, the greater the ideal distance to the other discourse coalition.

This figure illustrates the one-mode concept subtract-network with frames that appear at least 20 times in the media discourse. The size of the nodes is indicative of the frequency with which the concept appears in the selected newspaper articles, expressed as a numerical value. The link strength indicates the degree of connection between the nodes (actors), with stronger connections occurring when the nodes are shared by more actors and vice versa. The colours assigned to the nodes are as follows: light blue represents the electromobility narrative, green denotes the collective-transport narrative, yellow signifies the mobility-reduction narrative, dark blue is associated with the mobility-transition narrative, and pink is linked to the non-mobility narrative.

As with the actor-network, the pro-concept network is more strongly linked than the contra network. While the former forms a tight chain of arguments, the latter contains more loosely connected individual arguments.

The pro-discourse coalition argues for the tramway mainly within the ‘collective-transport-narrative’. From the ‘non-mobility-narrative’, it mainly uses aspects of participation and problems that the tramway can bring with it. Moreover, but less strongly, it argues for the tramway within the ‘mobility-reduction’ as well as the ‘mobility-transition’ narrative. The five most frequently used frames of the pro-discourse coalition are: the tramway should be built, has supra-regional importance and the overall project, is climate-friendly, profitable for commuters/the surrounding area and better. The contra-discourse coalition mainly uses the ‘non-mobility-narrative’ through aspects that contain strong concerns and NIMBY reactions. Less represented are ‘electromobility’ as well as ‘collective-transport’ narratives for alternative proposals to the tramway. The five most common frames are objections to the tramway, that the construction time is too long, that it is dangerous for cyclists and outdated, and the proposals of a high-speed bus system and modern alternatives.

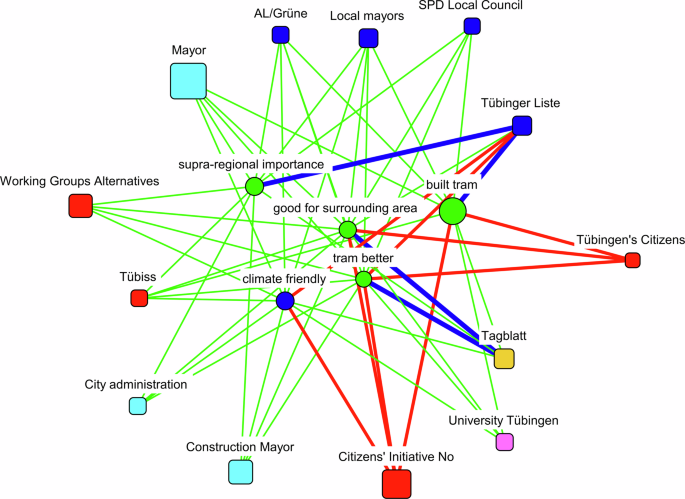

In Fig. 4, which shows the linking of actors and frames together, it becomes clear that the contra-discourse coalition takes up important pro-frames and negates them. It thus not only sets its own accents in the discourse, but also specifically attacks the most frequent and central arguments of the pro-discourse coalition: That the tramway should be built as a more convincing solution for the surrounding area/commuters and climate-friendly.

This figure illustrates the two-mode combined network with actors and frames that appear at least 50 times in the media discourse. The size of the nodes is indicative of the frequency with which the concept or actor appears in the selected newspaper articles, expressed as a numerical value. The link strength indicates the degree of connection between the nodes (actors and concepts), with stronger connections occurring when the nodes are shared by more actors or concepts are shared by more actors and vice versa. The colour green indicates approval, the colour red indicates disapproval, and the colour blue indicates neutrality. The node colours are as follows: red denotes civil society, light blue represents the city administration, yellow signifies associations/companies, dark blue indicates political actors, green denotes environmental groups, and pink denotes universities.

Discourse dynamics in media discourse

To examine the discourse development, concept subtract-networks are mapped in the four time periods. Period_1 (Fig. 5) is hardly polarised. The ‘non-mobility’ and ‘collective-transport’ narratives are particularly used in the discourse. The former picks up concerns about the tramway, financial and participation aspects; the latter argues for the tramway as well as possible alternative mobility systems. The five most common arguments are that the tramway should be built, that it is profitable for the surrounding area, that the alternatives should be checked, that the tramway is outdated and that modern alternatives are needed instead. The greatest consensus is that alternative mobility systems must be examined.

This figure illustrates the one-mode concept subtract-network of period_1 with the 23 most frequent frames. The size of the nodes is indicative of the frequency with which the concept appears in the selected newspaper articles, expressed as a numerical value. The link strength indicates the degree of connection between the nodes (actors), with stronger connections occurring when the nodes are shared by more actors and vice versa. The colours assigned to the nodes are as follows: The colours assigned to the nodes are as follows: light blue represents the electromobility narrative, green denotes the collective-transport narrative, yellow signifies the mobility-reduction narrative, dark blue is associated with the mobility-transition narrative, and pink is linked to the non-mobility narrative.

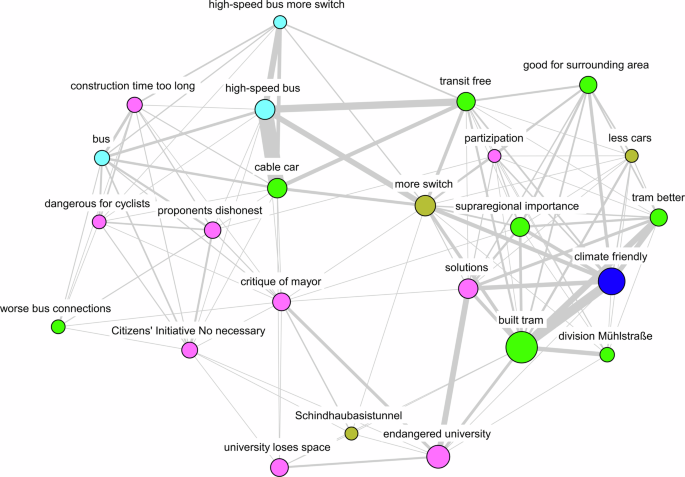

Period_2 (Fig. 6) is more polarised. In general, the possible negative effects that the tramway could have on sensitive research equipment and the areas of the University of Tübingen, and possible solutions are heavily negotiated by both coalitions in a sub-discourse (‘solutions’, ‘university endangered’, ‘university loses space’). On the pro-discourse coalition side, a chain of arguments is formed within the ‘collective-transport’ and ‘mobility-reduction’ narrative. Central frames are again that the tramway should be built, that it is climate-friendly and that it has a supra-regional significance. Besides, it will make more people switch from cars to public transport, and there are solutions to the problems that could arise for the university. On the contra-discourse coalition side, arguments are predominantly made in the ‘non-mobility’ and ‘electromobility’ narrative. The most frequent frames relate to mobility with the alternative proposal of express bus and cable car. They are also critical of the mayor, accuse the proponents of dishonesty and emphasise the need for the contra-citizens’ initiative.

This figure illustrates the one-mode concept subtract-network of period_2 with the 24 most frequent frames. The size of the nodes is indicative of the frequency with which the concept appears in the selected newspaper articles, expressed as a numerical value. The link strength indicates the degree of connection between the nodes (actors), with stronger connections occurring when the nodes are shared by more actors and vice versa. The colours assigned to the nodes are as follows: The colours assigned to the nodes are as follows: light blue represents the electromobility narrative, green denotes the collective-transport narrative, yellow signifies the mobility-reduction narrative, dark blue is associated with the mobility-transition narrative, and pink is linked to the non-mobility narrative.

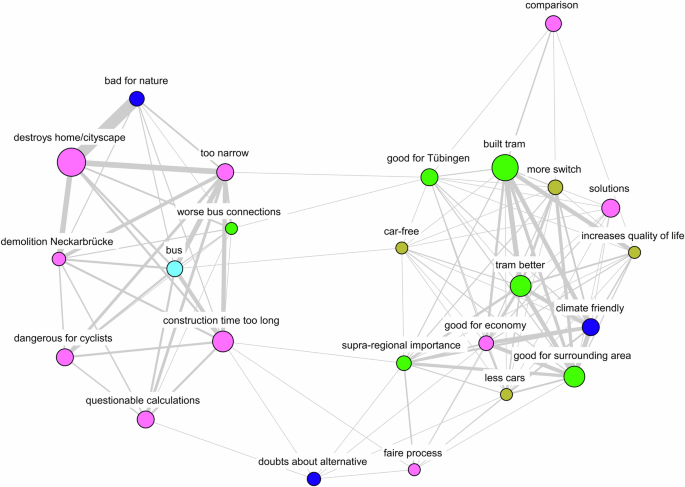

The media discourse is strongly polarised in Period_3 (Fig. 7). The pro-discourse coalition again features the ‘collective-transport-narrative’ most strongly. Equally strong are the ‘mobility-reduction’ and ‘non-mobility’ narratives. It suggests that the tramway should be built, that it is good for the surrounding area, better and climate-friendly, and that there are solutions to the problems that arise for the University of Tübingen’. While the pro-discourse coalition maintains its line of argumentation, the contra-discourse coalition places newly and very prominently that the tramway disturbs home/cityscape. It also argues that the construction time is too long, Tübingen is too narrow, the calculations are questionable and the tramway is dangerous for cyclists. Thus, in contrast to the previous period, it hardly offers any alternative proposals, but argues specifically against the tramway within the ‘non-mobility-narrative’.

This figure illustrates the one-mode concept subtract-network of period_3 with the 25 most frequent frames. The size of the nodes is indicative of the frequency with which the concept appears in the selected newspaper articles, expressed as a numerical value. The link strength indicates the degree of connection between the nodes (actors), with stronger connections occurring when the nodes are shared by more actors and vice versa. The colours assigned to the nodes are as follows: The colours assigned to the nodes are as follows: light blue represents the electromobility narrative, green denotes the collective-transport narrative, yellow signifies the mobility-reduction narrative, dark blue is associated with the mobility-transition narrative, and pink is linked to the non-mobility narrative.

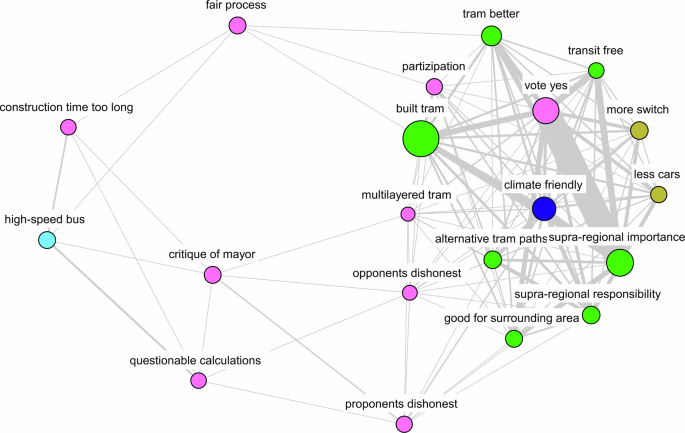

The month before the election (Period_4) can be attributed a high significance since voters often decide shortly before the election, and media play an important role here57,58. The pro-discourse coalition again mainly uses the ‘collective-transport’ and ‘mobility-reduction’ as well as the ‘non-mobility’ narrative (Fig. 8). Their five most frequent frames are that the tramway should be built, has a supra-regional significance, that one should ‘vote yes’ and that the tramway is climate-friendly and better. Interestingly, new frames have been added by the pro-discourse coalition or are more important: Besides the election appeal to ‘vote yes’, the frames ‘alternative paths’ in general and the ‘Österberg’ as an alternative route, in particular, have been added. These are arguments against the tramway. The pro-discourse coalition probably gets cold feet before the referendum and tries to adjust. The contra-discourse coalition negotiates in the ‘non-mobility’ narrative and also again in the ‘electromobility’ and ‘collective-transport’ narrative. It propagates the express bus alternative, criticises the mayor, finds the proponents dishonest, the construction time too long, and the calculations questionable. The discourse is held together by the demand to be fair in the debate.

This figure illustrates the one-mode concept subtract-network of period_4 with the 20 most frequent frames. The size of the nodes is indicative of the frequency with which the concept appears in the selected newspaper articles, expressed as a numerical value. The link strength indicates the degree of connection between the nodes (actors), with stronger connections occurring when the nodes are shared by more actors and vice versa. The colours assigned to the nodes are as follows: The colours assigned to the nodes are as follows: light blue represents the electromobility narrative, green denotes the collective-transport narrative, yellow signifies the mobility-reduction narrative, dark blue is associated with the mobility-transition narrative, and pink is linked to the non-mobility narrative.

Analysis of the brochure

The local brochure was delivered to all mailboxes in Tübingen at the end of August 2021 and presents the tramway and alternative plans on 21 pages. On eight further pages, mayor Palmer, the parties in the local council (Al/Grüne, SPD, Tübinger Liste, CDU, Die Linke, Die Fraktion, FDP), and the three citizens’ initiatives have their say with their own pleas. We analysed this brochure and coded 220 statements.

As Fig. 9 shows, the perspectives within the brochure are very polarised and fractured into two arenas, despite the low threshold. The pro-discourse coalition uses all narratives of the analytical grid except the ‘electromobility-narrative’. It most often argues that the tramway is climate-friendly, beneficial for the surrounding area, has a supra-regional importance, should be built and is better. Contrarily, the contra-discourse coalition uses the ‘non-mobility narrative’ most dominantly. The ‘electromobility’, ‘collective-transport’ and ‘mobility-transition’ narratives occur less often. It most often proclaims that the tramway is outdated, and the construction time is too long, that the Neckarbrücke will be demolished, that the tramway is dangerous for bicycles and that it disturbs the cityscape/homeland. The alternative mobility systems appear little. In general, the picture is like that in the media discourse. This means that self-portrayal and media-portrayal do not differ significantly. Interestingly, new frames emerge here, albeit very marginally, such as that the tramway is the best thing for the city and society and that the TüBus should complement it.

This figure illustrates the one-mode concept subtract-network of the brochure with frames that appear at least three times. The colours assigned to the nodes are as follows: The colours assigned to the nodes are as follows: light blue represents the electromobility narrative, green denotes the collective-transport narrative, yellow signifies the mobility-reduction narrative, dark blue is associated with the mobility-transition narrative, and pink is linked to the non-mobility narrative.

Discussion

The results with the most important findings of our study are discussed below with reference to the current literature.

As the analysis of Figs. 3–9 shows, the individual narratives of the analytical grid occur to varying degrees. Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4 summarise the results comparatively. It becomes clear that both, the four mobility narratives and the ‘non-mobility-narrative’ were strongly present in the discourse. Interestingly, there are clear differences and different emphases between the pro- and contra-discourse coalitions in how the narratives are used. While in the case of mobility, the proponents are strongly anchored in the ‘collective-transport’ as well as the ‘mobility-reduction’ narrative, the opponents rely on the ‘electromobility’ and ‘collective-transport’ narratives. Regarding the ‘non-mobility-narrative’, it can be stated that the contra-discourse coalition uses it more than the pro-discourse coalition. Moreover, the opponents use NIMBY arguments and urban planning aspects (e.g., ‘construction time too long’, ‘destroys home/townscape’), while the pro-discourse coalition negotiates financial and participation aspects. The fact that different discourse arenas are linked is due, on the one hand, to the complex topic and, on the other hand, to the nature of the counter-protest, which can be attested to have NIMBY-characteristics. However, the contra-discourse coalition does not embody a pure NIMBY protest but expanded its particular interests to include sustainability aspects by advocating for alternative mobility systems.

To promote the tramway, the pro-discourse coalition mainly used the less accepted narratives of ‘collective-transport’ and ‘mobility-reduction’. The tramway would have meant a strong intervention in the mobility culture and a change of the status quo—a challenging starting position29. In contrast, the contra-discourse coalition wanted to preserve Tübingen. Their alternatively proposed solutions to the tramway are based on the ‘electromobility’ and ‘collective-transport’ narratives. In the case of Tübingen, both hardly touch the status quo, as the TüBus is standard in Tübingen, i.e., part of the urban mobility culture. Expanding and retrofitting the bus fleet does not mean a major change for either the cityscape or usage—a more connectable starting point29,49. It is important to note that while the status quo is used as an argument, this obscures the fact that it is already changing and will continue to change as a result of the climate crisis.

Moreover, the contra-discourse coalition pleaded from the outset for ‘modern alternatives’ in contrast to the seemingly ‘outdated’ tramway and here cleverly picked up on Tübingen’s culture49. There are at least three reasons why it can be argued that Tübingen sees itself as a model city and a pioneer. First, when it comes to climate protection, Tübingen is known and ambitious throughout Germany6,7,59. Secondly, during the Covid-pandemic, Tübingen was in the media nationwide with the “Tübinger Model”60. Third, the University of Tübingen is one of only ten universities of excellence in Germany61 and the city is home to several leading research institutes. Tübingen is thus known for progress and used to progress. Building a tramway that is already running in many other cities and has a proven technology does not seem to fit in well with the city’s culture. To exaggerate: Tübingen would make headlines with flying taxis, but hardly with a tramway. However, the pro-discourse coalition just tried to score points with positive examples from other cities (‘comparison with other city’). Ruhrort15 concludes that a multi-optional mobility culture is emerging in big cities and that a narrative is needed that links individual advantages with the benefits of a more liveable city. It could, therefore, have been profitable to emphasise that the tramway would have profitably complemented the TüBus, e-scooters, car sharing and bicycles in Tübingen. Instead, the tramway was framed as competition or a threat to Tübingen’s mobility culture, which, according to Risom49, does not lead to acceptance.

Since Tübingen’s mobility culture is strongly characterised by cycling, the argument that the tramway would be dangerous for cyclists catches. The resulting impact and appeal55 were probably underestimated by the proponents. Part of the city culture is that people want to keep their pretty little Tübingen and that a tramway would disrupt the cityscape and sense of home. Here, the perceived loss of home11 due to the planned change of the city centre resonates. The contra-discourse coalition in Tübingen warns that the tramway would be “destructive to the city centre”62. It should be noted that the tramway would not have gone directly through the old town centre. The urban/rural conflict line is cleverly used. Although the concept of home is otherwise rather linked to the rural43, it is used here in an urban context: Tübingen’s old town appears as a threatened identity-forming space that needs to be protected and is therefore fought over17. That voters also voted against the tramway particularly because of these arguments is proven by the post-referendum survey55.

The argumentation of the pro-discourse coalition focuses on the fact that the tramway would be good for the surrounding area and climate-friendly, and on the supra-regional importance of the tramway. All these frames are far away and superordinate for a local project63. The advantages that the tramway would bring to the people of Tübingen and the city itself are marginal to non-existent. The fact that the quality of life in the city would be improved by fewer cars or cleaner air, and that out-commuters, the economy and local trade would also benefit, is hardly discussed in the discourse. However, studies clearly show that these reliefs would have been central to the acceptance of the new mobility system48,64. According to the post-referendum survey, ‘no’-voters doubted both that the benefits of the tramway would be as great as the proponents claim55 (91%) and that they would personally benefit (41%), citing the former as the most important reason for voting against the tramway. The results of the DNA coupled with the post-referendum survey highlight the fatal strategic flaw in the pro-discourse coalition’s argumentation: It was unable to convince the people of the benefits of the tramway in purely substantive and argumentative terms55.

Also, despite the focus on climate friendliness, the climate crisis was not brought to the local level2. It was always seen as a value in itself. Perhaps the pro-actors relied on the believe that this value is self-evident in a green showcase city like Tübingen, and that it does not need any (local) justification and can be taken for granted. In general, however, it can be assumed that citizens know little about the environmental consequences of their choice of transport mode35.

By focusing on the climate and the surrounding area, the pro-discourse coalition engaged in unwise agenda-setting, relied on the wrong frames, and failed to place solid arguments of advantage prominently in the discourse48. Instead, the wrong frames became imprinted on voters through the many repetitions. Thus, the pro-discourse coalition argued past the voters. A larger space in the discourse for the citizens’ council, which positioned itself in favour, could have been positive here. In contrast, with its frequent and central frames on the length of the construction period, the disfigurement of the city, the outdated technology, the demolition of the Neckar Bridge and the proclaimed danger for cyclists, the contra-discourse coalition focused strongly on the negative impacts for the people of Tübingen and their beloved city and pursued a NIMBY-strategy in the sense of against is the new for cf. 44,63. It also argued strongly against the central frames of the pro-discourse coalition.

Aspects of health protection due to lower air and noise pollution by the tramway, as well as social aspects, such as easing the housing market, barrier-free platforms, and fairer access to mobility for all people, were neglected or remained unspecified in the discourse. The freedom of transfers was praised with the fact that more people would leave their cars, but not with the fact that freedom from transfers also reduces stress and is therefore healthier65. Thus, the pro-discourse coalition did not grasp the multidimensionality of the mobility-transition and did not exploit this potential argumentatively.

As explained, the pro-discourse coalition argued strongly within the narratives of ‘collective-transport’ and ‘mobility-reduction’. Instead of fully telling the even less socially established/accepted narratives, important narrative elements were omitted. For the ‘mobility-reduction’ narrative, it was stated that the tramway would lead to fewer cars, more people would switch to public transport, and the city centre would become car-free, if necessary, by restricting individual traffic. However, it was not or only rarely said that car-free cities have a positive effect on health and quality of life, that cities become more liveable because public space is redistributed in favour of the people living there: People instead of cars are given space, green areas are enlarged or built. For example, the urban climate would also have benefited from the planned grass tracks. More green spaces in the city cool down on hot days66. The ‘mobility-reduction-narrative’—if completely told—creates a positive image of the future and tells a story that appeals to heart and mind45. By severely truncating and reducing the narrative to the elimination of the car—which is elementary beyond question15—it was arguably perceived more as a threat and menace to familiar and comfortable individual transport. The ‘collective-transport-narrative’ was also not told to its end: The tramway could have led to more equitable access to mobility for all. The tramway’s barrier-free stops would have ensured more inclusion. But this was hardly the subject of the discourse. By not finishing the narrative, the pro-discourse coalition failed to paint a positive and thus convincing, desired picture of Tübingen’s future that would meet with acceptance.

A strong frame of the contra-discourse coalition was that the tramway would be a danger for cyclists. Since Tübingen can be considered a city with a cycling culture, this argument caught on, which is also shown by the post-referendum survey55. The supporters hardly set any frames of their own here, but mostly only contradicted the proclaimed danger or even agreed with it. Only rarely was a reference made to improvements for cycling. Buses and cars, statistically the greatest danger, were only marginally mentioned as a source of danger in the discourse. Ironically, the pro-discourse coalition could not take advantage of the fact that two associations, the ADFC and the VCD, which explicitly advocate more safety for cyclists, promoted the tramway. They had a very weak discourse position. Making the tracks safer with bike-proof tracks was tested and found to be good, but then not consistently held in the discourse. The contra-discourse coalition took over the discursive field and could claim to represent the urban common good due to the seemingly overwhelming negative consequences for the people of Tübingen.

While the contra-discourse coalition used the ‘non-mobility’ narrative most strongly, it also served the ‘electromobility’ and, less often, the ‘collective-transport’ narrative by building an alternative public transport system—e-buses/high-speed buses—as a strong argument. It was also often highlighted that tramways have a big CO2-backpack and are therefore not climate-friendly. Basically, the e-(high-speed) buses as an alternative are a bogus argument because the TüBus would also have been retrofitted with the tramway, and the tramway would have been supplemented by a bus system (which, however, did not occur in the discourse). Many future scenarios overestimate “the power of conventional strategies to create real change”36, resulting in scenarios that are too similar to the status quo without including the necessary changes—as is true for the ‘electromobility-narrative’ favoured by the contra-discourse coalition. Nevertheless, the contra-discourse coalition additionally legitimises itself through this apparent green alternative and claims to represent the common good: citizens could thereby be for climate protection and against the tramway at the same time, which might have been decisive for the green milieu in Tübingen. The counter-protest was thus a NIMBY-protest, as many NIMBY arguments were used, but not a pure one, as aspects of the sustainability and mobility-transition were also addressed. By this, voting against the tramway was thus also connectable for sustainability-conscious voters11,40.

In the negotiation process for the tramway in Tübingen, the contra-discourse coalition used a clever mix of universalist and particularist arguments: The green alternative of (high-speed) e-buses cleverly flanked the NIMBY-reactions and urban planning fears, which was a convincing combination. This combination picked up both people for whom urban concerns were paramount63 and people for whom the universalist sustainability reference was important, socially embedding egocentric interests35. Here, a line of conflict between the city of Tübingen and the surrounding rural area emerges11. While in protests against power lines the countryside protests—electricity is produced in the countryside and consumed in the city11—it is the other way round in the case of Tübingen. The surrounding area is to be better connected and the people in the city do not see why they should agree to this and apparently lose spatial profits.

The opponents did not dominate the discourse but varied their line of argument more than the proponents. The contra-discourse networks are also less strongly linked than the pro-discourse networks. Thus, it can be argued that opponents could more easily selectively avail themselves of the individual arguments and dock on, while supporters had to agree with the entire pro-chain of arguments. This finding is supported by the representative post-referendum survey55, which found that opponents had more arguments in terms of numbers, but that the individual arguments did not receive as high an approval rating in each case. The citizens who voted against the tramway had different reasons for doing so. Those who voted for the tramway in the referendum, however, often did so for one and the same reasons. Hoeft et al.11 conclude in this context that it is challenging for citizens’ initiatives to meet different expectations. In Tübingen, this seems to have succeeded, as the opposing side consisted not only of a citizens’ initiative, but also of local council factions and, e.g., the “Schwäbischer Heimatbund”, each of which focused on different aspects.

Moreover, while the pro-discourse coalition also argued strongly for the alternative assessment in the beginning, this is in contradiction with the fact that, at the same time, it already strongly supported the tramway from the beginning and also considered it better. Thus, the frame that the tramway is better than other public transport solutions has been frequent and central from the beginning. Mayor Palmer, e.g., said even before the results of the alternatives assessment were available that he did not see an alternative with equal performance67,68. Thus, their decision in favour of the tramway seemed to be fixed even before the alternatives assessment, which does not seem very credible. Especially considering that infrastructure planning should not be presented as without alternatives18. Because Tübingen’s discourse was already divided into two sides long before the referendum, there were also few mediating actors. Mayor Palmer, e.g., was clearly positioned from the beginning. Interestingly, he gave in shortly before the referendum, abandoned his position and brought up alternative routes for the tramway. The fact that even Palmer, as the biggest advocate, wavered shortly before the referendum could have had an additional negative impact on the voting behaviour.

To summerise, cities are key players in shaping the mobility transition. For this, they must combine transport and climate policy goals and create social acceptance. Even though Tübingen offered an ideal setting and starting position, the construction of a tramway to protect the climate was rejected by its citizens in a referendum. To explain this, we interpreted the case as a narrative-communicative challenge rather than a technical endeavour and conducted a DNA of the media discourse before the referendum as well as of the information brochure, combined with a narrative analysis grid to identify discursive pitfalls on the way to a sustainable city. Proponents and opponents were conceptualised as competing discourse coalitions striving for hegemony. This relational approach of Hajer’s discourse coalitions framework, which focuses on the coalitions of actors, combined with our analytical grid of Holden et al.’s mobility grand narratives, provides a novel theoretical lens that goes beyond frameworks that cover narratives of socio-technical or deliberative processes. We answered the following three sub-questions:

(1) Which actors and frames shaped the discourse, and how did it develop? The discourse was dynamic, a wide variety of actors from politics, civil society and business were involved; and the argumentation concerned different fields of discourse due to the complex socio-technical matter (wicked problem). The pro-discourse coalition included more and more diverse actors. The discourse polarised over the four time periods. Central actors were mayor Palmer and the citizens’ initiative against the tramway. The arguments in favour of the tramway were strongly based on the different mobility narratives: It is climate-friendly, good for the surrounding area and has a supra-regional significance; the arguments against the tramway were more based on the ‘non-mobility-narrative’: it is outdated, the construction time is too long, it is dangerous for cyclists, and it disturbs the home/cityscape. Self-portrayal (Info-Broschüre) and external portrayal (media discourse) of the actors strongly coincide.

(2) To what extent was Tübingen’s tramway negotiated in the nexus of the mobility-transition? The pro-discourse coalition negotiated the tramway very much within the nexus of the mobility-transition. Especially in the ‘collective-transport’ and ‘mobility-reduction’ narrative. The ‘non-mobility’ and ‘mobility-transition’ narratives were also used. The contra-discourse coalition, however, negotiated the tramway less within the mobility nexus, but more within the ‘non-mobility-narrative’. It also used the ‘electromobility’ and occasionally the ‘collective-transport’ narrative. In the discourse, the tramway was fought over in various ways, often in the nexus of the mobility-transition, but often apart from it, especially by the contra-discourse coalition: It skilfully combined particular interests and sustainability aspects. This had implications for connectivity.

(3) To what extent were the opponents of the tramway more convincing in discourse? The contra-discourse coalition unfolded an enormous discursive power due to its high narrative connectivity and can, therefore, be seen as more convincing in the discourse. Besides, the pro-discourse coalition favoured the success of the counter-protest, as it showed discursive weaknesses, deficiencies in communication and inadequately negotiated the socio-technical questions around the mobility-transition in Tübingen. The tramway would have brought a new kind of mobility to Tübingen and changed the status quo. Therefore, the starting position for the pro-discourse coalition was more difficult, but it dominated the discourse in terms of frequency and centrality, which it could not claim for itself.

The pro-discourse coalition was argumentatively weaker in the discourse and made discursive mistakes because (1) instead of focusing on the advantages for Tübingen’s citizens, it focused on global climate protection and the advantages for commuters, (2) it did not exploit the potential of the multidimensionality of the mobility-transition, (3) it told the mobility-transition narratives incompletely or shortened it unfavourably and thus did not paint a positive picture of the future, (4) it left the field to the opponents in terms of argumentation, and (5) it lost credibility by taking an early position on the tramway and changing tack late. The contra-discourse coalition was additionally more convincing because (1) it focused on the disadvantages for the people of Tübingen and used discursive lines of conflict, (2) it promoted a green alternative and thus skilfully flanked the NIMBY-frames, (3) it hardly attacked the status quo, (4) it argued appropriately for the urban mobility culture and (5) it did not form a densely linked chain of arguments.

To master the mobility transition through future infrastructure projects, the following recommendations for action for local actors can be derived from this analysis: Infrastructure projects that are to make cities more socio-ecologically sustainable must include narrative strategies and be communicated convincingly:

-

Make targeted use of the transformative potential of frames and narratives. Since a serious mobility-transition challenges the status quo, a sensitive approach must be taken. Do not tell still unknown/less accepted narratives in a trimmed way.

-

Focus on the (local) benefits of mobility measures and make them tangible. Create positive future narratives.

-

Observe urban mobility culture to recognise and eliminate possible blockades at an early stage. Actively counter fears and propose solutions.

-

Exploit the potential of multidimensionality: a transformation of mobility is good for the climate, health, social coexistence and the housing market.

An experimental transition governance approach as examined by Loorbach et al.25 in a case study in Rotterdam could help to shape urban special and mobility policies.

The present study contributes to the existing literature on sustainable urban mobility transitions from a discursive perspective. Furthermore, it goes beyond the current research by employing a relational discourse coalitions approach, which allows for a more nuanced understanding of the dynamics of discursive interactions. Since Tübingen offered an ideal setting and still failed, this case-study focused mobility transition as discourse-communicative challenge of socially embedded narratives instead of mobility transition as technical endeavour. Linking the DNA to the discourse coalition approach and the mobility narratives, as well as discussing them on the basis of current research on protest and the mobility-transition, proved to be fruitful for local policy practice. The transferability of the results needs to be tested. To generate more far-reaching policy advice for local actors, it would be interesting to conduct a comparative DNA of different cities and triangulating interviews as well as to explore how local actors can make climate protection a tangible local story to overcome the status quo and deal with the fact that the future will remain uncertain. As shown, various discursive pitfalls lurk on the way to sustainable cities. Empirical discourse-analytical results and narratives are crucial for making cities socio-ecologically sustainable and for successfully shaping the mobility-transition so that emissions finally fall in the transport sector as well.

Methods

Data and operationalization

DNA is a mixed-method-approach and combines discourse analysis and social network analysis: Central arguments, actors and content-related argumentation linkages, discourse dynamics, hegemony, actor constellations and topic areas can be identified23,69.

Since media are important for actors to communicate their narratives35, newspaper articles can be profitably used as data. Our data corpus consists of online articles from Tübingen’s local newspaper “Schwäbisches Tagblatt” and the local information brochure on the tramway10. Since 70% of Tübingen’s citizens informed themselves via the “Tagblatt” and as many as 85% via the brochure55, the media discourse supplemented by the brochure can be attributed to an opinion-forming function and it can be assumed that the public discourse was decisively shaped by these58. The media discourse not only reproduces the social discourse (albeit in a distorted and selective way), but also constitutes it70,71 and has an impact on electoral decisions58.

The selection of the online articles was made via the search mask of the website of the “Schwäbisches Tagblatt”: Keyword (different words for the tramway): Innenstadtstrecke OR Stadtbahn OR Innenstadttrasse; Area: Kreis Tübingen; Type: Artikel; Period: bestimmter Zeitraum: from (left blank) to 26.09.2021.

The 935 article hits were sorted out manually. Live tickers, thematically deviating articles or those without statements were not included. 140 articles were included in the analysis. The oldest article is from 2016.

The discourse was coded using the software Discourse Network Analyzer (dna, version 2.0-beta25; https://www.philipleifeld.com/software/software.html)23,69. Statements (direct/indirect expressions of opinion on the tramway, not mere descriptions) were marked and four types of information were manually coded: Actor’s name; Organisation; Frame; Agreement/disagreement (dummy variable) with frame.

Statements could be coded multiple times, also if they could be attributed to organisations but not to individuals and statements by journalists in commentaries were coded as their opinion. The concept categories were formed deductively and inductively and each assigned to a superordinate narrative (Supplementary Table 1). To analyse the discourse development, the period of analysis was divided into four time periods based on key events (Table 1).

The operationalisation was as follows: Discourse is the totality of frames and narratives as well as their actors and network relations within the selected text data. Frames are the coded concepts that can be assigned to narratives. The three mobility grand narratives of Holden et al.29 are used as the analytical grid and supplemented by a general ‘mobility-transition-narrative’ and a ‘non-mobility-narrative’. The latter includes all frames that do not concern the mobility-transition, in particular NIMBY, urban planning or construction, economic and participation aspects.

With the visualisation software Visone (https://visone.ethz.ch/html/download.html), the coded data was visualised and analysed as social networks. Using the quick layout function, an algorithm positions similar nodes next to each other72,73. Networks consist of nodes and links that express a relationship. ‘One-mode’ networks represent either actors or concepts as nodes; ‘two-mode’ networks both (affiliation networks). In actor networks, people/organisations (nodes) are linked (via links) if they share the same view on at least one frame. In concept networks, frames (nodes) are connected if at least one actor uses both. Congruence networks show shared, and conflict networks show opposing opinions. Subtract networks visualise conflict coalitions by subtracting the conflict network from the congruence network. It shows whether congruence or rejection predominates32. If the rejection links are removed, the network only shows connections between nodes where there is more agreement.

The analysis of degree centrality reveals the importance of actors/frames in the network. The more links a node has, the more central the node is74. The frequency indicates how often actors/frames appear in the discourse. This is visualised via the node sizes. The link weight indicates how similar actors are in the discourse. The more concepts actors (do not) share, the greater/smaller the link weight. Thus, actors who are connected as groups/clusters can be interpreted as a discourse coalition32. To make the network structure more visible, the threshold value can be adjusted32.

Newspaper articles are a common data basis in the social sciences, as they provide readily available and dynamic data. However, they follow a different logic than science, which leads to methodological problems or limitations75,76. We have to bear in mind that they are not written for scientific analysis but follow other logic. There are various mechanisms by which the media distort reporting through the selection and framing of topics. This leads to methodological problems and limitations in interpretation, which are often discussed in research75,76 and must be considered. It is important to note that the discourse network analysis method is limited to examining the actors and content present in the selected data set. Consequently, some individuals may have been excluded from the analysis due to their absence in the newspaper articles under consideration. The journalists selected the individuals referenced in the articles based on their expertise in the relevant field. Local newspapers serve as an important source of information and have an influence on the readers’ opinions.

In addition, the delimitation of categories is difficult, and the discourse is abstracted. To mitigate these problems and ensure validity and reliability, several coding runs were carried out at intervals. The detailed codebook attempts to create transparency. It can be assumed that the possible distortions in the newspaper articles are the same over the study period, as the newspaper publisher did not undergo any major changes (e.g., change of funding). For reasons of triangulation, the self-portrayals of the actors in the municipal information brochure were also analysed.

Responses