Association of fine particulate matter constituents with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the effect modification of genetic susceptibility

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), characterized by persistent airflow obstruction, ranked as the fourth leading cause of death in 2021, with a global age-standardized death rate of 45.2 (40.7–49.8) per 100,000 population1. It is estimated that COPD will cost the global economy INT$4.3 trillion in 2020–50, and thus investing in effective interventions against COPD is urgent2. Globally, smoking remains the most important risk factor for COPD3. However, 25–45% of COPD patients are thought to have never smoked4, indicating that other factors have a substantial role as well. More than 70% of DALYs linked to COPD are reported to be caused by smoking and ambient particulate matter, and air pollution and other environmental factors are progressively emerging as significant risk factors for COPD in low-income and middle-income countries5. Thus, it is speculated that ambient PM2.5 may become an increasingly significant contributor to COPD and deserve more attention from healthcare providers and policymakers6.

Numerous studies have shown a link between PM2.5 exposure and the onset, progression, and mortality related to COPD7,8. Nonetheless, PM2.5 is a complicated blend that consists of water-soluble and organic materials originating from multiple sources, and the understanding of the varying harmful effects of different components remains unclear. Epidemiological evidence on PM2.5 components that are most detrimental to respiratory health is crucial for developing more refined air quality standards and leading to more accurate risk assessments. Currently, limited studies have assessed the impact of specific PM2.5 components on respiratory health events. Some research observed the short-term effects of several PM2.5 components on respiratory admissions, hospitalizations, and emergency department (ED) visits9,10,11,12,13. For example, ref. 11 reported excess rates (ERs) of COPD admission and ED visits associated with PM2.5, primary and secondary organic carbon. However, the health effects of PM2.5 are often cumulative. Only five studies to date have explored the long-term effect of PM2.5 constituents on lung function and COPD-related events. However, one study was cross-sectional14, and others focused only on elemental/black carbon15,16,17,18. The risk of incident COPD with prolonged exposure to PM2.5 components has not yet been evaluated. Consequently, it is essential to carry out a cohort study to investigate if long-term exposure to PM2.5 components would elevate the risk of incident COPD and identify which specific constituents contribute most significantly to this risk, enabling targeted emission control efforts.

Genetic influences are also crucial in the development of COPD. A polygenic risk score (PRS) that combines various genetic variants linked to the risk of COPD and its related phenotypes, derived from genome-wide association studies (GWAS), has been indicated to capture the overall impact of genetic predisposition and serves as a crucial indicator for predicting the incident of new COPD cases19. Additionally, the role of gene-environment interactions in the pathogenesis of COPD is becoming increasingly elucidated20,21. However, no study to date has evaluated the interactions between PM2.5 constituents and genetic susceptibility, which may help pinpointing populations at greater risks and advance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind COPD.

To explore the relationship between prolonged exposure to PM2.5 constituents and the risk of developing COPD, we carried out a prospective cohort study using data from the UK Biobank. Furthermore, another objective was to pinpoint the specific components that exerted the most significant influence on this risk and assess whether there are synergistic effects between PM2.5 constituents and genetic factors.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

The current study included a total of 489,773 participants, of whom 19,488 newly diagnosed COPD patients were documented during a median follow-up time of 12.79 years. The baseline characteristics of the included participants based on COPD status were presented in Table 1. Compared to non-COPD individuals, participants with COPD tended to be older, male, White, obese, less physically active, and have a higher TDI. Moreover, there were lower proportions of being highly educated and current drinkers among COPD patients, while they had a higher proportion of retired/unemployed, current/former smokers, passive smokers, having lower household income and unhealthy diets. The averaged exposure levels of participants during the follow-up period were 8.93 ± 1.73, 0.67 ± 0.30, 1.73 ± 0.49, 1.19 ± 0.20, 2.08 ± 0.39, and 1.57 ± 0.32 μg/m3 for PM2.5, EC, OM, NH4+, NO3−, and SO42−, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). Spearman correlations between PM2.5 constituents were described in Supplementary Table S3. The geographic distribution of PM2.5 and various constituents’ concentrations in our current study has been mapped in Supplementary Fig. S1.

PM2.5 components and the risk of incident COPD

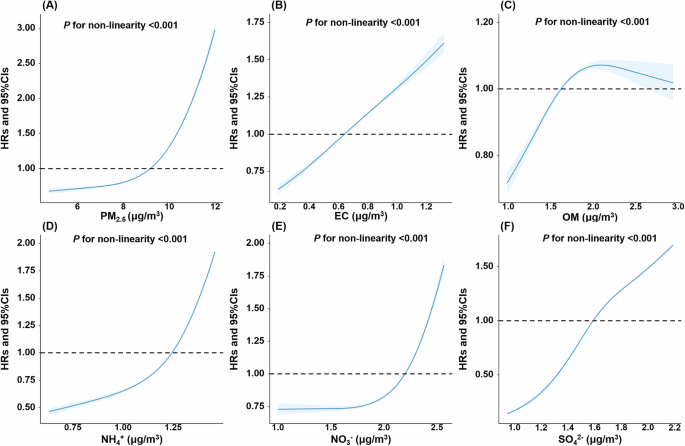

We applied two models (single-pollutant model and multi-pollutants model) to evaluate the association of long-term exposure to PM2.5 and its components with the risk of incident COPD. Table 2 shows the detailed Cox regression results of the single-pollutant model. We observed positive associations of PM2.5 components and the risk of incident COPD in crude model, and significant associations were also found after adjusting multiple covariates. The adjusted HRs and 95% CIs were 1.58 (1.56, 1.61), 1.35 (1.33, 1.38), 1.10 (1.08, 1.12), 1.42 (1.41, 1.43), 1.30 (1.28, 1.32), and 1.24 (1.24, 1.24) with per IQR increment in PM2.5, EC, OM, NH4+, NO3−, and SO42−, respectively. Most of the sensitivity analyses were basically consistent with the primary findings (Supplementary Tables S4–8). For example, after additionally adjusting baseline asthma status, the HRs and 95% CIs were 1.57 (1.54, 1.59), 1.34 (1.32, 1.37), 1.10 (1.08, 1.12), 1.41 (1.40, 1.42), 1.28 (1.26, 1.31), and 1.24 (1.23, 1.24) with per IQR increment in PM2.5, EC, OM, NH4+, NO3−, and SO42−, respectively (Supplementary Table S7). Notably, when using time-varying Cox proportional hazard models that treated exposure as time-varying variables, the effect estimation decreased largely but still positive, with HRs and 95% CIs 1.12 (1.09, 1.14), 1.06 (1.04, 1.08), 1.04 (1.02, 1.06), 1.19 (1.16, 1.22), 1.09 (1.08, 1.11), and 1.16 (1.14, 1.19) for PM2.5, EC, OM, NH4+, NO3−, and SO42−, respectively (Supplementary Table S9). Figure 1 presents the exposure-response relationships of PM2.5 total mass and its components with the risk of incident COPD. All the relationships were nonlinear with P value for the linearity test <0.001. For the majority of components, the risk increased sharply at higher exposure concentrations. In contrast, the curve for OM showed a sharp escalation at low to moderate exposure levels.

Models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnic, household income, education level, employment status, smoking status, passive smoking, drinking status, MET, Townsend deprivation index, BMI, and diet score. COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, PM2.5 fine particulate matter with diameter <2.5 μm, EC elemental carbon, NH4+ ammonium, NO3− nitrate, OM organic matter, SO42− sulfate. A represents the exposure–response curve between PM2.5 total mass and the risk of COPD. B–F represent the exposure–response curves for EC, OM, NH4+, NO3− and SO42−, respectively.

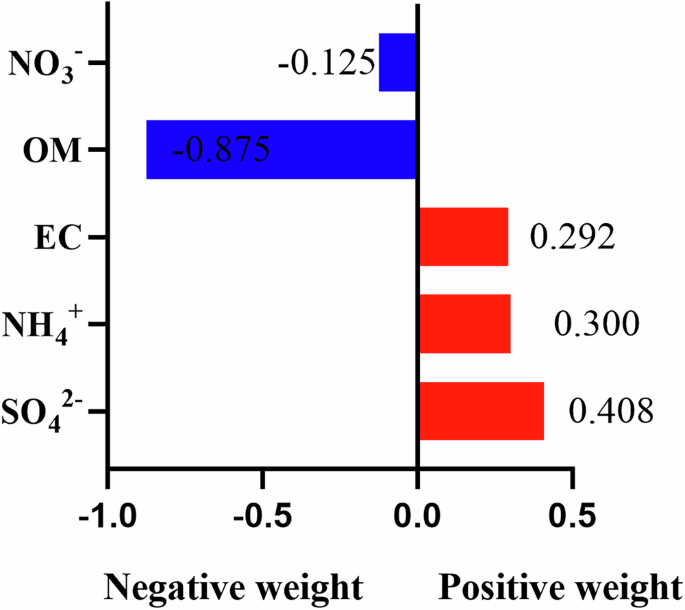

Combined exposure to five PM2.5 constituents was also positively associated with the risk of COPD (HR: 1.66, 95% CI:1.62–1.69), where each quantile increase in the mixture was related to a 50% (95% CI 48–53%) increase in the risk of COPD. The detailed results of the multi-pollutants model are shown in Supplementary Table S10. Figure 2 visualizes the contribution weight of each component to the mixed effects, with SO42− (40.8%) being the primary positive contributor to the risk of COPD, followed by NH4+ (30.0%) and EC (29.2%).

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, PM2.5 fine particulate matter with diameter <2.5 μm, EC elemental carbon, NH4+ ammonium, NO3− nitrate, OM organic matter, SO42− sulfate.

Associations of PRS and genetic risk with incident COPD

The distribution of PRS in the current study was shown in Supplementary Table S11. We observed the increased risk of incident COPD per IQR increase in PRS (HR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.15–1.20). The risk of incident COPD increased significantly from low to high genetic risk (HR 1.29 (95% CI: 1.25, 1.34), for high genetic risk); P value for trend <0.001) (Supplementary Table S12).

Joint effects of genetic susceptibility and PM2.5 total mass, as well as its specific components on the risk of COPD

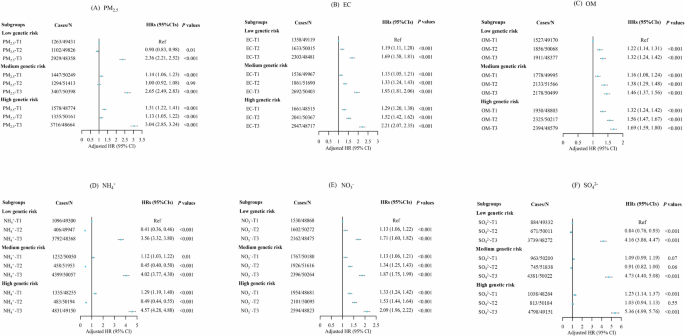

Figure 3 displays the joint effects of genetic susceptibility and PM2.5 total mass (panel A) as well as its specific components (B–F) on the risk of COPD. Individuals with a strong genetic predisposition who are subject to elevated levels of PM2.5 components are at a significantly higher risk of developing COPD than those who have a low genetic vulnerability and are exposed to minimal pollution (adjusted HR: PM2.5 total mass, 3.04 (95% CI 2.85, 3.24), EC, 2.21 (95% CI 2.07, 2.35), OM, 1.69 (95% CI 1.59, 1.80), NH4+, 4.57 (95% CI 4.28, 4.88), NO3−, 2.09 (95% CI 1.96, 2.22), and SO42−, 5.36 (95% CI 4.99, 5.76).

A shows the joint effect between genetic susceptibility and PM2.5 total mass. B–F represent the joint effects of genetic susceptibility and EC, OM, NH4+, NO3−, and SO42−, respectively. PM2.5 fine particulate matter with diameter <2.5 μm, EC elemental carbon, NH4+ ammonium, NO3− nitrate, OM organic matter, SO42− sulfate. Note: Each PM2.5 constituent was categorized into three levels (T1, T2, T3) according to the tertile of constituent concentration.

Interaction effects of PM2.5 components with genetic risk

The multiplicative and additive interactions of PM2.5 components with genetic risk are summarized in Table 3. We found a multiplicative interaction between SO42− and PRS (P for interaction <0.001). There were synergistic additive interactions between genetic risk and PM2.5 total mass, EC, NH4+, and SO42− (RERI, AP >0, and SI >1). Among individuals who have a high genetic predisposition and are exposed to high levels of pollution, the synergistic effects accounted for 10–18% of the total risk of COPD. The RERI and 95% CI was 0.96 (0.74, 1.17), 0.73 (0.54, 0.91), 0.22 (0.09, 0.35) and 0.37 (0.22, 0.52) for SO42, NH4+, EC, and PM2.5, respectively.

Discussion

Our research initially revealed that prolonged exposure to PM2.5 components correlates with an increased risk of developing COPD, and SO42− was the main contributing constituent. Given the large sample size, we were able to investigate the modification effect of genetic factors on above associations, and we found synergistic effects between genetic susceptibility and SO42, NH4+, EC, and PM2.5. When examining the combined effects, individuals with a strong genetic predisposition who are exposed to elevated levels of PM2.5 components exhibited the highest likelihood of developing COPD.

Our study found that long-term exposure to PM2.5 increased the risk of incident COPD, in line with previous studies22,23,24. However, current evidence on associations between PM2.5 components and respiratory diseases remains limited and mainly focused on carbonaceous components. A case-crossover study from Taiwan revealed a significant link between short-term exposure to EC and an increase in emergency room visits related to COPD25. Lin et al observed increased rates of COPD hospitalization associated with increased concentrations of organic carbon11. A prior cohort study indicated that long-term exposure to EC had an adverse impact on COPD hospitalizations and mortality15. A cohort study based on six US metropolitan regions indicated a positive association between prolonged exposure to BC and increased percent emphysema16. The negative impact of BC on decreased lung function was also demonstrated by two cohort studies within elderly and urban women, respectively17,18. Only one cross-sectional study in China provided fresh epidemiological evidence indicating that prolonged exposure to several PM2.5 components (OM, BC, NO3−, NH4+, and SO42−) were linked to diminished function function14. To our knowledge, our research was the first cohort study identifying associations of incident COPD with long-term exposure to various constituents (EC, OM, NO3−, NH4+, and SO42−).

In our study, the QgC model showed joint exposure to PM2.5 components contributes to the risk of COPD, where SO42−, NH4+, and EC were responsible for this positive effect. OM and NO3− had adverse effects on incident COPD in the single-pollutant model rather than the QgC model, which may be due to the ability of addressing the multicollinearity issues among high-correlation components within QgC model. Both OM and EC are carbonaceous components and mainly originate from combustion-related emissions (e.g., biomass combustion, vehicle, and industrial emissions) (Supplementary Table S13), thus they have a strong correlation (r = 0.98). Water-soluble inorganic ions (SO42−, NO3−, and NH4+) accounted for a large proportion of PM2.5 components, which were mainly transformed by SO2 and NOx from coal combustion and vehicle exhaust26,27. NH4+ and NO3− have the same precursor substance (NOx) and they predominantly present as ammonium nitrate instead of a separate component10, thus their correlation is strong (r = 0.70). Consequently, the impact of OM and NO3− on COPD was likely confounded by EC and NH4+ in the single-pollutant Cox model.

Synergistic interactions between genetic susceptibility and PM2.5, SO42−, NH4+, and EC were observed. The interactions between PM2.5 and genetic susceptibility is plausible as evidence has demonstrated that susceptible genotype such as GST gene mediated in the inflammation, oxidative stress, and lung function changes induced by PM2.528,29. However, current evidence on interactions between PM2.5 components and gene is scarce. We found SO42− interact with PRS on both additive and multiplicative scales, suggesting that it may play an important role in the biological mechanisms of PM2.5 induced COPD. It is reported that SO42− was mainly responsible for inflammation and oxidative stress triggered by short-term traffic-related pollutants exposure, which may be the process of PM2.5-induced COPD30,31. Overall, our study underscored that tailored prevention in population groups with high genetic susceptibility would be more valuable and lead to a greater reduction in COPD incidence as compared to the general population.

Potential mechanisms of PM2.5-induced COPD mainly involve oxidative stress, inflammatory response, epigenetic alterations, and so on32. Prolonged exposure to PM2.5 has been demonstrated to be associated with pulmonary function damage, emphysematous changes, and lung inflammation33. Probable mechanisms of specific PM2.5 components on respiratory disease have also been proposed. Carbonaceous particles were demonstrated to significantly induce pulmonary function impairment and contribute to COPD by inducing oxidative stress and inflammation34. An animal experiment revealed that both short-term exposure to insoluble PM2.5 particles and chronic exposure to the water-soluble extract of PM2.5 resulted in significant lung injury35. Experimental evidence from rats exposed to diesel exhaust particles suggested that black carbon may induce COPD-like pathophysiology36. It is reported that sulfates could induce the generation of highly reactive oxygen species by transforming insoluble and less toxic metal oxides into soluble metal ions, activate genes associated with tumor development, and play a role in the formation of secondary organic and elemental carbon particles, ultimately heightening health risks37. Notably, small airway dysfunction (SAD) is a key pathology in early COPD. A recent study also indicated that SO2, a precursor of SO42−, is one of the important contributors to SAD38. The exact mechanisms by which components of PM2.5 influence the development of COPD are still to be investigated comprehensively in future studies.

This prospective cohort study included several strengths. First, the large-scale sample ensured the statistical power and robustness of the results. Second, apart from using a single-pollutant model, we also applied the QgC model to evaluate the combined effects of PM2.5 constituents on incident COPD and find crucial components for targeted emission control. Third, we considered the dynamic change of residential addresses and exposure concentrations during the follow-up period, which could reduce some exposure bias. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the current study only evaluated the primary constituents of PM2.5 without considering other possibly relevant components. Second, we defined PM2.5 exposure levels based on the concentrations measured around residential addresses, without accounting for the timing and location of outdoor activities, potentially introducing exposure misclassification. Third, although our models accounted for several covariates, we were still unable to mitigate the possible residual confounding effects stemming from covariates that could not be measured or were not accessible. Fourth, estimating the average exposure concentration during the period of follow-up for each participant may induce some time bias as the exposure duration between COPD and non-COPD groups was different. Finally, the subjects were predominantly of European ancestry, necessitating the cautious extrapolation to other ethnic populations.

In summary, our research first demonstrated that long-term exposure to chemical components of PM2.5 may increase the risk of incident COPD, with SO42−, NH4+, and EC identified as key harmful components. This finding underscored the importance of mitigating specific PM2.5 constituents to decrease the COPD risk and pave the way for more tailored public health recommendations. By investigating genetic susceptibility, this research could inform targeted prevention strategies for vulnerable populations, potentially diminishing COPD rates through improved air quality and lifestyle modifications. Additionally, we uncovered potential interactions between PM2.5 components and genetic predispositions, facilitating researchers further investigating the underlying mechanisms of gene-environment interactions related to COPD.

Methods

Study design and population

The UK Biobank is a large population-based prospective cohort study enrolling more than 0.5 million adults aged 37 to 73 years between 2006 and 2010 across 22 assessment centers. We used the collected data about sociodemographics, lifestyle, anthropometric measurements, genotypes, and health-related outcomes from the touchscreen questionnaire, physical measurements, blood samples, and medical records. More details of the study protocol of the UK Biobank have been described before39.

Data from 502,479 participants were available for our analysis. Participants with baseline COPD (n = 12,647) and missing PM2.5 constituent data (n = 59) were excluded. A total of 489,773 participants were selected to evaluate associations between PM2.5 components and the risk of incident COPD. Additionally, we further excluded participants without genetic data (n = 14,850) and non-White European (n = 27,649), and 447,274 subjects were chosen for gene-related analysis to investigate the impact of genetic susceptibility.

Exposure assessment

The key components of PM2.5, including SO42−, NO3−, NH4+, EC, OM, as well as PM2.5 total mass were considered in this current study. The exposure dataset we used is a model output from the European Monitoring and Evaluation Program model applied to the UK (EMEP4UK) driven by Weather and Research Forecast model meteorology (WRF)40. It provides UK estimates of daily averaged atmospheric composition at 3 × 3 km² grid for the years 2002 to 2021. A more detailed methodology has been described previously41,42. The EMEP4UK model has been assessed both in the UK and globally, demonstrating a strong correlation between modeled and measured concentrations43,44. We matched the individual exposure concentrations based on the geocode and calculated the time-weighted average exposure level considering dynamic changes of residential addresses like the prior literature reported45. The average annual pollutant concentrations during participants’ follow-up period are represented as the long-term exposure indicator45,46,47,48.

Ascertainment of outcomes

Participants with COPD diagnosis at the baseline and subsequent follow-ups were confirmed by first occurrences of health-related outcomes in UKB, through linkage to a variety of sources including primary care records, hospital admissions, death registries, and self-reported data (based on physician diagnosis and subsequently checked with nurses). COPD was identified through the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) code (J40-J44), and the date when the code was first recorded across any of the sources listed above was used as the time of COPD onset. Each participant was followed up from the date of entering the assessment center to the date of COPD onset, loss to follow-up, death, or end of follow-up on December 31, 2021, whichever came first.

Covariates

The included covariates were consistent with prior literature22,24. Annual household income was categorized into <£31,000 and ≥£31,000 groups based on UK median gross household income. Both smoking and drinking status included previous, current, and never smokers/drinkers. Whether participants were passive smokers was defined according to prior study criteria22. The Townsend Deprivation Index was used to reflect relative deprivation in a given area, with higher scores indicating a greater level of deprivation. The Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) acted as a measure of physical activity, determined by the total MET minutes accumulated weekly across all activities. The healthy diet score was constructed based on prior literature49 and considered various dietary factors, including vegetables, fruits, fish, unprocessed red meat, and processed meat. This healthy dietary score ranged from 0 to 5, with one point awarded for each factor that met the health criteria.

PRS calculation

The genotype data were derived from UKB and were quality-controlled50. We constructed weighted PRS in the European population using independent SNPs linked to COPD with P < 5 × 10−8 and minor allele frequency (MAF) >0.05, based on a prior COPD GWAS study with the largest sample to date51. This approach is consistent with the recent research from UKB, and there is no linkage disequilibrium among the selected SNPs (r2 ≤ 0.1 in a 1000-kb window)52. Detailed information about the SNPs were provided in Supplementary Table S1. The formula for constructing PRS aligned with earlier literature49. The PRS was finally categorized into three groups (low, median and high genetic risk) based on tertiles.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive baseline characteristics were presented as means ± standard deviations for continuous variables, and numbers (proportions) for categorical variables. Missing covariates were imputed as median or a missing indicator category for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Spearman correlation coefficients between PM2.5 constituents were performed. The main analysis applied Cox proportional hazard models to examine associations between PM2.5 chemical constituents and incident COPD within the single-pollutant model adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, annual household income, education level, employment status, Townsend Deprivation Index, smoking status, passive smoking, drinking status, MET, BMI, and healthy diet score. Schoenfeld residuals were used to evaluate the proportional hazards assumption, and no violations were discovered. The results were expressed in terms of hazard ratios (HRs) along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each interquartile range (IQR) increase in PM2.5 components. Moreover, the restricted cubic spline (RCS) model with three degrees of freedom was utilized to visualize the exposure-response (E-R) relationship between PM2.5 components and COPD onset. The curves were constrained to the middle 95th percentile of pollutant concentrations.

To investigate the mixed effects of PM2.5 components on incident COPD, we further conducted a multi-pollutant model using quantile g-computation (QgC). This approach enables valid estimation of both the combined effects of pollutant mixtures and the contribution of a single component, even when directional homogeneity or linearity is not satisfied. In addition, the QgC model can address multicollinearity issues among high-correlation components and more details about the model can be found from the prior literature53.

To evaluate the modifying effect of genetic susceptibility on associations of PM2.5 components and the risk of incident COPD, we investigated interactions between them on both additive and multiplicative scales. We included the interaction term for each PM2.5 component and PRS into the model, and P for interaction <0.05 indicated a statistically significant multiplicative interaction. Additionally, the additive interaction was assessed by calculating the relative excess risk (RERI), attributable proportion (AP) due to the interaction and synergy index (SI), along with their 95% confidence intervals. Confidence intervals of RERI and AP do not contain 0, and SI does not contain 1, indicating additive interactions existed. Moreover, we evaluated the joint effects of PM2.5 components exposure levels (stratified into three tertiles) and genetic risk (low, medium and high). Participants with low genetic risk and low pollutant exposure were regarded as the reference group and others with different combinations were assessed the risk of COPD respectively.

We performed multiple sensitivity analyses to assess the reliability of our findings: (1) Restricting the analysis to individuals who had lived at the same address for more than 5 years; (2) Limiting the analysis to participants with complete covariate data; (3) Excluding incident cases that occurred during the first year of follow-up; (4) Additionally adjusting the baseline asthma status to reduce the effect of asthma-COPD overlap on our main findings; (5) Excluding participants with occupations related to an increased risk for COPD like previously reported54 to mitigate the potential influence of occupational exposure. (6) Using time-varying Cox proportional hazard models that treated PM2.5 and its components as time-varying variables. All statistical analyses were conducted in R program version3.4.0.

Responses