Systematic review and meta-analysis on fully automated digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia

Introduction

The prevalence of insomnia varies from 5% to 50% depending on the definition and diagnostic criteria used in epidemiological studies1. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) and the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition (ICSD-3), insomnia disorder is characterized by difficulties in initiating, maintaining, or waking up early from sleep, resulting in impaired daytime functioning2,3. In DSM-5, insomnia disorder is diagnosed if sleep problems persist for at least 3 months and occur at least 3 days a week. The ICSD-3 distinguishes between short-term insomnia disorder, lasting less than 3 months, and chronic insomnia disorder, lasting more than 3 months. In the 2010s, when these stringent criteria were applied, the prevalence of insomnia disorder was generally between 6% and 10%. Recent epidemiological studies have estimated the prevalence of short-term insomnia disorder at 11.2% in Europe, 16.3% in Canada, and 16.8% in the Americas, indicating an increase from previous estimates4,5,6,7. Insomnia disorder often leads to decreased attention and concentration, contributing to higher accident rates, and long-term consequences such as major depressive disorder, hypertension, myocardial infarction, absenteeism, reduced productivity, diminished quality of life, and increased economic impact1,8,9,10,11. Consequently, the high prevalence of insomnia disorder may result in significant social and economic burdens, underscoring the necessity for effective management strategies.

Various clinical practice guidelines on insomnia recommend cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as the standard treatment12,13,14. CBT-I, an evidence-based, non-pharmacological approach, integrates components such as cognitive restructuring, sleep restriction, stimulus control, sleep hygiene education, and relaxation and has been proven effective in treating insomnia15,16,17. However, actual clinical implementation faces challenges due to factors like limited awareness, accessibility issues, a shortage of therapists, significant treatment duration and effort, and high costs. As a result, patients with insomnia often receive prescriptions for sleeping pills, which can cause side effects including tolerance, dependence, increased fall risk, and daytime drowsiness; the long-term side effects remain uncertain13,18,19,20. Therefore, a new treatment or delivery method is needed to address the limitations of CBT-I, ensuring it remains a safe, effective, and sustainable primary treatment.

In this context, digital CBT-I (dCBT-I) was developed to address the limitations of traditional face-to-face CBT-I, enabling the delivery of CBT-I components through digital technologies like telephone, internet, and web without the need to visit clinics or hospitals. Over the last 20 years, dCBT-I has been consistently studied21,22,23,24. dCBT-I has generally shown a large effect size in patients with insomnia according to several meta-analyses, proving effective also in patients with depression and anxiety disorders, which are common comorbidities of insomnia25,26,27. Drawing on these clinical evidence, digital medical devices (DMDs) have been developed. The number of prescription DMD products reviewed and approved by regulatory agencies globally is on the rise28. These prescription DMDs can be monitored by clinicians post-prescription with minimal involvement, allowing patients to proceed with treatment via customized feedback from the DMD algorithm. Thus, symptoms of insomnia can be alleviated without a therapist’s intervention, highlighting one of the significant benefits of fully automated dCBT-I (FA dCBT-I)29,30,31. Such FA dCBT-I promises to enhance cost-effectiveness and access to treatment for insomnia32,33.

However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no systematic reviews and meta-analyses that have directly analyzed FA dCBT-I interventions25,27,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. Research by Soh et al., Deng et al., and Lee et al. conducted subgroup analyses on FA dCBT-I, revealing a large effect size for insomnia severity. Nonetheless these studies only covered literature until January 2022, included a limited number of studies, and addressed only simple effect sizes compared to inconsistent control groups for insomnia severity27,36,38. Three studies performing network meta-analysis indicated varying effect size rankings for sleep-related outcomes for FA dCBT-I, with the study by Forma et al. focusing soley on specific FA dCBT-I product40,41,42. Moreover, while adherence is a crucial factor for realizing the potential of digital interventions, research on adherence and its influence on effect size remains scarce27,43. Consequently, there is a pressing need for updated systematic reviews and meta-analyses to comprehensively assess the effectiveness of FA dCBT-I44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52.

The objective of this meta-analysis was to assess the effectiveness of FA dCBT-I interventions for insomnia symptoms. We aimed to investigate the impact of FA dCBT-I on insomnia severity, sleep diary parameters, and intervention adherence, and conducted subgroup analyses to compare insomnia severity across various consistently categorized control groups. Additionally, we executed meta-regression analyses to identify variables influencing insomnia severity and explain heterogeneity.

Results

Study flow

Study selection was depicted using the PRISMA flow diagram as illustrated in Fig. 1. Initially, 3101 documents were identified through the search strategy. After duplicates were removed, 1974 documents underwent titles and abstracts screening. Of these, 129 documents were fully reviewed, resulting in 29 articles being included in the meta-analysis.

This diagram shows the number of articles identified in each database through this study, and the number of studies included and excluded by the systematic review process. A total of 3101 articles were identified from four databases, and 129 articles remained after the deduplication and screening process. A total of 29 studies were included after the full text review.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 29 studies included in the meta-analysis are summarized in Table 1. Among these, 12 were conducted in Europe, 7 in the United States, 6 in Oceania, and 4 in Asia. All included studies employed a parallel design; 4 were three-arm comparisons, while the remained were two-arm comparisons. The control groups included 10 waitlist, 9 online education about sleep, 5 placebo, 3 treatment as usual (TAU), 2 dCBT-I with therapist support, 1 face-to-face CBT-I, 1 dCBT for anxiety, and 1 three good things (TGT) exercise. The TGT exercise is a simple diary-like exercise that involves listing three good things that happened and providing a written explanation of why they happened49. It was set as a control because there is research showing a correlation between positive emotions and sleep53.

A total of 9475 participants were included in this meta-analysis, with 4847 randomly assigned to the FA dCBT-I group, where 73.30% were female. The mean age of participants was 45.71 ± 14.23 years. Six studies focused on populations with comorbid psychiatric disorders (5 on depression and 1 on anxiety), and three targeted populations with cancer, traumatic brain injury, and hypertension, respectively. Two studies focused on pregnant women. The FA dCBT-I group had 4 to 8 sessions, averaging 5.86 sessions. Two studies assessed intervention adherence. Watanabe et al. measured it by the rate of sessions completed against the number of scheduled sessions, and Yang et al. used the Treatment Components Adherence Scale (TCAS)50,51,54. Conversely, 19 studies reported the number of participants who completed the intervention, with an average completion rate for FA dCBT-I of 59.33%, ranging from 16.67% to 85.71%.

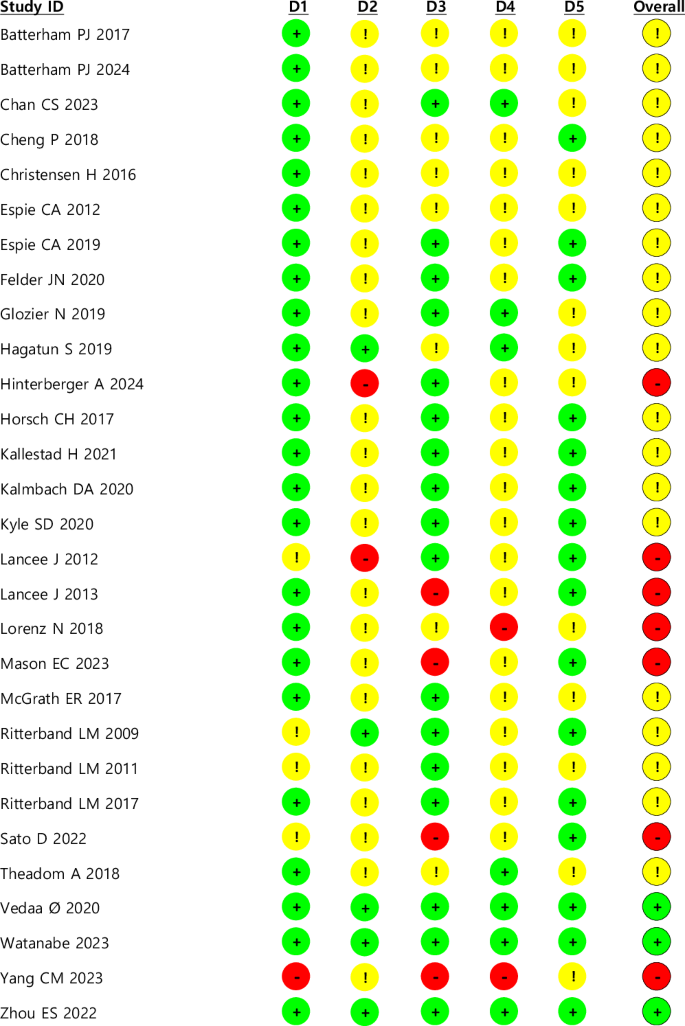

Risk of bias

Figure 2 displays the results of the risk of bias assessment using the RoB 2.0 tool. Three studies were judged to have a low risk of bias, 19 had some concerns, and 7 were considered high risk. The risk of bias was generally some concern in the Deviation from intended intervention and Measurement of the outcomes domains. The reason for the risk of bias in the Deviation from intended intervention domain was that most studies were open label due to the nature of the intervention, and they showed high dropout rates and low completion rate of intervention. In the Measurement of the outcomes domain, the reason was that most of the open label and sleep-related intervention outcome measurement methods were self-reported methods.

This presents the results of the risk of bias assessment using the RoB 2.0 tool for the included randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The assessment covered five domains: (1) the randomization process, (2) deviations from intended interventions, (3) missing outcome data, (4) measurement of the outcome, and (5) selection of the reported result. Each study was assessed according to established criteria, and the overall risk of bias was determined based on domain-specific ratings. Studies with low risk of bias in all domains were classified as having an overall low risk, whereas studies with at least one high-risk domain were classified as high risk. Among the studies, 3 were judged to have a low risk of bias (green), 19 exhibited some concerns (yellow), and 7 were classified as high risk (red). The most frequently observed concerns were related to the domains of (2) deviation from intended intervention and (4) measurement of outcomes.

Post-treatment effect

Insomnia severity measurements varied across included studies: Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI), Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS), and Sleep-50. When multiple scales were reported, the ISI was selected. The post-treatment effect of FA dCBT-I on insomnia severity showed a moderate to large effect size (Fig. 3; SMD = −0.71; 95% CI: −0.88, −0.54; p < 0.001; k = 32). Statistical heterogeneity across studies for effect sizes was considerable (Fig. 3; I2 = 91%; Q = 330.81; df = 31; p < 0.001).

This figure presents a forest plot summarizing the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals for various studies comparing FA dCBT-I with control interventions. The control groups consisted of different conditions: (1) TAU, (2) placebo, (3) paper and pencil CBT-I delivered by e-mail vs waitlist, (4) electronic CBT-I vs waitlist, (5) waitlist, (6) TGT exercise, (7) waitlist, (8) dCBT-I with therapist support, (9) SHUTi vs patient education about sleep, and (10) SHUTi-BWHS vs patient education about sleep. The post-treatment effect of FA dCBT-I on insomnia severity showed a moderate to large effect size (SMD = −0.71; 95% CI: −0.88, −0.54; p < 0.001; k = 32; I2 = 91%).

Sleep diary outcomes revealed a small effect for total sleep time (TST) (Supplementary Fig. 1; SMD = 0.19; 95% CI: 0.07, 0.31; p = 0.002; I2 = 73%; k = 24), and small to moderate effects for sleep efficiency (SE) (Supplementary Fig. 2; SMD = 0.45; 95% CI: 0.27, 0.64; p < 0.001; I2 = 88%; k = 25), sleep onset latency (SOL) (Supplementary Fig. 3; SMD = −0.39; 95% CI: −0.53, -0.24; p < 0.001; I2 = 79%; k = 23), and wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO) (Supplementary Fig. 4; SMD = −0.38; 95% CI: -0.57, −0.19; p < 0.001; I2 = 86%; k = 20).

Post-treatment effects by control type classification

The control group was divided into six categories: waitlist, TAU, placebo, online education about sleep, non-sleep psychological intervention, and CBT-I with therapist support. FA dCBT-I showed a large effect compared to waitlist (Fig. 4; SMD = −0.88; 95% CI: −1.07, −0.70; p < 0.001; I2 = 67%; k = 11), placebo (Fig. 4; SMD = −0.98; 95% CI: −1.30, −0.67; p < 0.001; I2 = 72%; k = 3), and online education about sleep (Fig. 4; SMD = −0.93; 95% CI: −1.07, −0.79; p < 0.001; I2 = 68%; k = 10). It also demonstrated a moderate to large effect compared to TAU (Fig. 4; SMD = −0.74; 95% CI: −1.16, −0.67; p < 0.001; I2 = 76%; k = 3). CBT-I with therapist support (Fig. 4; SMD = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.85; p < 0.001; I2 = 16%; k = 3) showed a moderate effect relative to FA dCBT-I.

This figure presents the standardized mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals for FA dCBT-I compared to six control groups: waitlist, treatment as usual (TAU), placebo, online education about sleep, non-sleep psychological intervention, and CBT-I with therapist support. The intervention groups consisted of different conditions: (1) electronic CBT-I, (2) paper and pencil CBT-I delivered by e-mail, (3) SHUTi, and (4) SHUTi-BWHS. FA dCBT-I demonstrated a large effect compared to waitlist (SMD = −0.88; 95% CI: −1.07, -0.70; p < 0.001; I² = 67%; k = 11), placebo (SMD = −0.98; 95% CI: −1.30, −0.67; p < 0.001; I² = 72%; k = 3), and online education about sleep (SMD = −0.93; 95% CI: −1.07, −0.79; p < 0.001; I² = 68%; k = 10). Additionally, FA dCBT-I showed a moderate to large effect compared to TAU (SMD = −0.74; 95% CI: −1.16, -0.67; p < 0.001; I² = 76%; k = 3). In contrast, CBT-I with therapist support showed a moderate effect relative to FA dCBT-I (SMD = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.85; p < 0.001; I² = 16%; k = 3).

Sensitivity analysis

When studies that did not report the inclusion or exclusion of participants with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were excluded, FA dCBT-I demonstrated a moderate to large effect (Supplementary Fig. 5; SMD = −0.72; 95% CI: −0.88, −0.55; p < 0.001; I² = 90%; k = 28)49,55,56. The same was observed when studies that did not investigate participants with a history of suicide attempts were excluded (Supplementary Fig. 6; SMD = −0.73; 95% CI: −0.98, −0.47; p < 0.001; I² = 94%; k = 14)29,46,47,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63.

Furthermore, when studies that did not report stable use of hypnotic medications were excluded, FA dCBT-I demonstrated a large effect size (Supplementary Fig. 7; SMD = –0.88; 95% CI: −1.05, −0.70; p < 0.001; I² = 85%; k = 20)46,47,57,63,64,65,66,67. This was primarily because all studies comparing therapist-guided CBT-I and FA dCBT-I were excluded47,51,66. Lastly, robust effect was observed even after excluding studies investigating non-algorithm based FA dCBT-I (Supplementary Fig. 8; SMD = −0.71; 95% CI: −0.88, −0.54; p < 0.001; I² = 91%; k = 32)48,51,65,66.

Follow-up treatment effect

The follow-up effects on insomnia severity were all moderate; short term (Supplementary Fig. 9; SMD = −0.54; 95% CI: −0.84, −0.23; p < 0.001; I2 = 80%; k = 7), medium term (Supplementary Fig. 9; SMD = −0.54; 95% CI: −0.91, −0.18; p = 0.004; I2 = 95%; k = 10), and long term (Supplementary Fig. 9; SMD = −0.76; 95% CI: −0.87, −0.65; p < 0.001; I2 = 0%; k = 4). There was no statistically significant difference when comparing follow-up periods (p = 0.24).

The follow-up effects on TST in sleep diary demonstrated statistically significant small effects in the short term and long term; short term (Supplementary Fig. 10; SMD = 0.31; 95% CI: 0.16, 0.46; p < 0.001; I2 = 0%; k = 5), medium term (Supplementary Fig. 10; SMD = −0.05; 95% CI: −0.29, −0.20; p = 0.72; I2 = 80%; k = 7), long term (Supplementary Fig. 10; SMD = 0.28; 95% CI: 0.05, 0.50; p = 0.02; I2 = 56%; k = 3). There was a statistically significant difference when compared by follow-up periods (p = 0.04).

The follow-up effect on SE showed a statistically significant moderate effect in the short and long terms; short term (Supplementary Fig. 11; SMD = 0.56; 95% CI: 0.14, 0.97; p = 0.009; I2 = 86%; k = 5), medium term (Supplementary Fig. 11; SMD = 0.34; 95% CI: −0.03, 0.72; p = 0.07; I2 = 91%; k = 6), long term (Supplementary Fig. 11; SMD = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.46, 0.76; p < 0.001; I2 = 0%; k = 3). There was no statistically significant difference when compared by follow-up periods (p = 0.43).

The follow-up effect on SOL demonstrated a statistically significant effect in the short and long terms, specifically, a large effect in the short term and a moderate effect in the long term; short term (Supplementary Fig. 12; SMD = −0.96; 95% CI: −1.81, −0.10; p = 0.03; I2 = 96%; k = 5), medium term (Supplementary Fig. 12; SMD = −0.23; 95% CI: −0.54, 0.08; p = 0.15; I2 = 87%; k = 6), long term (Supplementary Fig. 12; SMD = −0.47; 95% CI: −0.62, -0.32; p < 0.001; I2 = 0%; k = 3). No statistically significant differences were observed when comparisons were made across follow-up periods (p = 0.19).

The follow-up effect on WASO yield a statistically significant small effect in both the medium and long terms; short term (Supplementary Fig. 13; SMD = −1.04; 95% CI: −2.17, 0.10; p = 0.07; I2 = 96%; k = 3), medium term (Supplementary Fig. 13; SMD = −0.32; 95% CI: −0.58, −0.05; p = 0.02; I2 = 82%; k = 6), long term (Supplementary Fig. 13; SMD = −0.45; 95% CI: −0.63, −0.26; p < 0.001; I2 = 36%; k = 3). No statistically significant differences were observed when compared by follow-up periods (p = 0.41).

Treatment completion rate

The pooled treatment completion rate of 19 studies, reporting the number of patients completing the intervention, was 55.90% (95% CI: 50.19%, 61.61%). We classified these 19 studies into subgroups based on whether their completion rate was above or below 55.14%. Subgroup analysis showed that studies with above 55.90% (Supplementary Fig. 14; SMD = −0.81; 95% CI: −1.09, −0.53; p < 0.001; I2 = 87%; k = 13) had a greater effect than those with below 55.90% (Supplementary Fig. 14; SMD = −0.48; 95% CI: −0.85, −0.12; p = 0.009; I2 = 95%; k = 9), although the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.17).

Publication bias

The funnel plot for post-treatment insomnia severity is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 15. The result of Egger’s test revealed no statistically significant publication bias (t = 1.34, df = 30, p = 0.19).

Meta-regression analysis

The results of the meta-regression analysis are displayed in Table 2. Of the nine moderator variables evaluated, only the control type showed statistical significance in affecting insomnia severity, with a coefficient of 0.184 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.083 to 0.284 (p < 0.001).

Discussion

Although prescription digital medical devices (DMDs) have entered the market, their value is not definitively established, prompting many nations to opt for temporary over permanent reimbursement as they evaluate real-world evidence. Consequently, further research into the treatment effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of DMDs is essential28,68,69. This meta-analysis was aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of FA dCBT-I, a principle technology in current prescription DMDs, in ameliorating insomnia symptoms, thus contributing to the scientific foundation supporting of DMDs.

FA dCBT-I demonstrated moderate to large effects on insomnia severity compared to controls across 29 included studies. Previous studies analyzing FA dCBT-I through subgroup analyses reported large effects on insomnia, yet this study noted a relatively smaller estimated effect size compared to those in earlier research27,36,38. The study by Soh et al. conducted subgroup analyses based on the presence or absence of therapist guidance, including 17 studies on unguided dCBT-I, and found that unguided dCBT-I was more efficacious. Deng et al. also performed a subgroup analysis by guidance modality, identifying large effect sizes in both animated therapist dCBT-I (8 studies) and unguided dCBT-I (10 studies). Lee et al. analyzed 14 studies on FA dCBT-I among insomnia patients with comorbid depression and anxiety, revealing a large effect size of SMD = −0.81 (95% CI: −1.04, −0.59). These differences in results may stem from variations in study participant and intervention inclusion/exclusion criteria or could be attributed to this study’s inclusion of all recent publications.

In sleep diaries, TST demonstrated a small effect, whereas other parameters showed small to moderate effects. The finding that TST in sleep diaries had a relatively small effect compared to other parameters suggests that factors enhancing sleep quality contribute to improved sleep efficiency by bettering sleep maintenance, depth, and time to sleep onset, rather than directly influencing TST. One reason for pronounced impact on insomnia severity compared to sleep diaries might be that both are assessed through subjective methods. However, sleep diaries target more specific sleep patterns, indicating that the measurement of insomnia severity is more influenced by subjective experience. This finding is consistent with a high risk of bias across studies in the fourth domain (measurement of the outcome). Similar trends have been observed in previous studies, where the effects on TST were generally smaller than those on other sleep parameters, and the effects on insomnia severity were greater than those in sleep diary outcomes. This pattern has been documented in prior meta-analyses on dCBT-I effects on sleep by Zachariae et al., Tsai et al., Deng et al., and Lee et al., as well as in traditional CBT-I studies25,27,37,38,70.

In examining the FA dCBT-I by follow-up period, it was observed that there was no statistically significant difference in all parameters depending on the period, except for TST, indicating that the effect was sustained in the long term. For TST, medium-term follow-up showed greater effects for the control group, though these were not statistically significant, with considerable heterogeneity. The study by Zachariae et al. summarized the results from a follow-up period ranging from 4 to 48 weeks, reporting a large effect in insomnia severity (k = 5), a medium effect in SE, WASO (k = 4), and a small effect in SOL, TST (k = 4)25. However, SOL, WASO, and TST did not show statistically significant effects, and the number of included studies was limited. Other studies also reported the follow-up effect, but direct comparison of effect sizes is challenging because they are calculated as the mean difference34,35,36.

Subgroup analyses with consistent control group classification revealed that FA dCBT-I exhibited significantly higher effect sizes compared to all control groups, except when compared with Non-sleep psychological intervention and CBT-I with therapist support. Nevertheless, CBT-I with therapist support, such as face-to-face CBT-I, demonstrated greater effects than FA dCBT-I. This suggest that a hybrid approach, combining therapist support with prescription DMDs, might enhance the effectiveness of DMDs for insomnia treatment. Consistent with this observation, Deng et al. reported the largest effect size (Hedges’s g = −1.19; 95% CI: −1.45, −0.92) in their subgroup analysis for therapist-guided interventions38.

We hypothesized that the efficacy of prescription DMDs as a treatment option comparable to traditional CBT-I would not only depend on completing the intervention but also consistently adhering to self-help practices. Therefore, this study aimed to examine adherence and its impact on effect size. However, since only two studies reported on adherence and used different methods for measuring it, we performed a subgroup analysis based on the pooled intervention completion rate, including only studies reporting complete participation. Although the effect size was larger in studies with above pooled completion rates, the difference was not statistically significant, and meta-regression results also indicated that the completion rate did not significantly influence the effect size.

In a recent study by Thorndike et al. adherence was defined as the intervention completion rate among 1565 participants in a real-world setting, with a rate of 46.8%, which was lower than the completion rate observed in this meta-analysis71. Because there is no standardized tool to measure adherence, completion rate is often reported as adherence. However, the findings of this meta-analysis emphasize that completion rate alone is not the critical factor influencing the effectiveness of prescribed DMDs, and suggest the need to focus on adherence.

Although there are many DMD products preparing to enter the market, the regulatory framework for implementing adherence assessment is not yet ready72. Schwartz et al. analyzed the application of the existing drug adherence framework to DMD at the micro, mesa, and macro levels73. Further research is needed to standardize this framework, and clinical trials or real-world studies that attempt to apply it are needed.

CBT-I interventions encompass various components such as sleep restriction, stimulus control, cognitive restructuring, relaxation, and sleep hygiene education. While multicomponent CBT-I offers comprehensive treatment, its complexity may reduce adherence in unguided digital formats. On the other hand, pure sleep restriction therapy, which is simpler and more structured, may achieve higher adherence in a digital format74,75. This suggests a need to tailor digital CBT-I interventions based on the feasibility of delivering specific components and their adherence potential in a fully automated setting.

One limitation of this study, similar to previous research, is the high heterogeneity observed in most synthesized outcomes. Meta-regression analysis identified control types as the sole variable significantly influencing heterogeneity and treatment effects. Although heterogeneity was reduced in subgroup analyses by control type, it persisted underscoring the need for further investigation into heterogeneity sources. Another limitation is that, despite intentions to analyze quality of life and adherence in the protocol, only two studies reported quality of life data, preventing any further analysis. Lastly, the dynamic nature of DMD was not represented. Given the evolving nature of DMD as software medical devices prone to updates, further research is necessary to consider these characteristics in effectiveness evaluations72.

This study focused on evaluating the efficacy of FA dCBT-I in ameliorating insomnia symptoms to ascertain the therapeutic potential of prescription DMD. FA dCBT-I demonstrated moderate to large effects compared to the control group, yet it did not achieve the efficacy of CBT-I with therapist support. This indicates that a hybrid approach combining therapist support might be needed for prescription DMD to evolve into a more effective treatment option. Further research that focuses on standardizing adherence measurement methods and the continuous development of DMD is essential, as it will provide specific guidance for maximizing the potential of prescription DMD.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook and was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines76,77 (Supplementary Table 1). The protocol for this review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42024526617).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria consisted of adults aged 18 years or older with insomnia, either diagnosed or self-reported, using evidence-based diagnostic criteria. Exclusion criteria included individuals under 18 years; those with prior CBT-I treatment; unstable users of sleeping pills; individuals with a history of suicide attempts, alcohol abuse, or addiction; those with sleep apnea; shift workers; and individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

FA dCBT-I was defined as a digitally delivered CBT-I intervention (via mobile app, email, computer, phone, etc.) without therapist guidance, regardless of the delivery platform. The intervention must include at least one cognitive and one behavioral component and last a minimum of 4 weeks. Control groups included in the studies were Waitlist, Treatment as Usual (TAU), Placebo, sleep education, and therapist-guided CBT-I.

The primary outcomes were self-reported insomnia severity using measures such as the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Secondary outcomes included sleep diary measures Total Sleep Time (TST), Sleep Efficiency (SE), Wakefulness After Sleep Onset (WASO), and Sleep Onset Latency (SOL) and adherence to FA dCBT- I. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included.

Search strategy

We searched the PubMed, CENTRAL, Embase and PsycINFO databases for studies published up to March 31, 2024. Searches were conducted using natural language, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and Boolean operators, focusing on intervention, intervention delivery and population. The complete search strategy by database is detailed in the Supplementary Table 2.

Study selection

After removing duplicates, two authors (J.W.H. and G.E.L) independently screened the titles and abstracts based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Following this preliminary screening, they reviewed the full texts to determine the final selection of studies for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, or through discussion with a third reviewer (J.Y.K) when consensus could not be reached. If the studies did not investigate or report some of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study, we included those publications in the meta-analysis to maintain comprehensiveness. However, we performed sensitivity analyses to assess the potential impact of including these studies on the overall meta-analysis results.

Data extraction

Two authors (J.W.H and G.E.L) independently extracted data from the included studies, which encompassed information on study characteristics such as title, authors, year of publication, journal, study area, study design, participant recruitment method, randomization method, and participant details including number of participants, sex, mean age, and standard deviation. Information on the intervention included components, period, and outcome measures, as well as pre, post, and follow-up outcomes (mean, standard deviation, standard error, and 95% confidence interval) for both intervention and control groups. Missing data prompted, contact with the corresponding author, and studies were excluded if there was no response. All disagreements were managed by consensus, or with the aid of a third reviewer (J.Y.K.) if unresolved.

Risk of bias assessment

Two authors (J.W.H. and G.E.L.) independently assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for RCTs (RoB 2.0), which includes five domains: (1) Randomization process; (2) Deviation from intended intervention; (3) Missing outcome data; (4) Measurement of the outcomes; (5) Selection of the reported result. Disagreements were resolved through consensus, or if unresolved, through discussion with a third reviewer (J.H.W.).

Data synthesis and analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using RevMan 5.4, Microsoft Excel, and R version 4.2.3. Data from the extracted studies were synthesized using a random effects model. For this synthesis, the mean difference (MD) and standard deviation (SD) of both the intervention and control groups post-intervention or follow-up observation were used to pool the standardized mean difference (SMD) with a 95% CI78. The follow-up periods were categorized into three durations for analysis: 3 months or less (Short term), more than 3 months and 6 months or less (Medium term), and more than 6 months (Long term). The heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the Cochran Q and I2 tests. A p-value of less than 0.1 indicates heterogeneity. The I2 value ranges denote levels of heterogeneity as follows: 0–40% is low, 30–60% is moderate, 50–90% is substantial, and 75% or more is considered considerable. Publication bias was expressed through a funnel plot, and if the Egger test result p < 0.05, it was considered as publication bias.

In subgroup analysis, the control group classifications from the included studies were consistently applied. In terms of adherence, synthesizing data was unfeasible due to the lack of standardized reporting and the fact that most RCTs only reported the number of participants who completed the sessions. Consequently, the completion rate of the intervention was calculated by dividing the number of participants who completed all prescribed intervention sessions by the number of participants assigned to the intervention group. This completion rate was synthesized based on the meta-analysis method using Excel by Neyeloff et al.79. Subgroup analysis also involved categorizing cases into those with above or below pooled completion rate.

Further, meta-regression analysis using R was undertaken to investigate variables influencing the effect size and heterogeneity in insomnia severity. The moderator variables included the number of participants, average age of participants, the proportion of female participants, presence of comorbidities, classification of the control group, number of intervention sessions, duration of the intervention, baseline severity of insomnia, and the intervention completion rate.

Responses