Regulatory considerations for successful implementation of digital endpoints in clinical trials for drug development

Introduction

Advances in Digital Health Technologies (DHTs) have opened new opportunities in clinical trials by providing innovative methods to collect information from participants1. DHTs consist of hardware and/or software and can be used on various computing platforms, such as mobile phones, smartwatches, etc.2,3. More advanced DHTs also leverage artificial intelligence and machine learning for data processing and analysis4. The use of DHTs in clinical trials offers several potential advantages by providing richer data sets (e.g., continuous data collection in participant’s home environment vs. snapshots/episodic recordings during clinical visits) or performing objective measurements without recall bias that flaws Patient Reported Outcomes, leading to a better understanding of the efficacy and safety of the interventions studied1,3,5,6. Via remote data acquisition, DHTs can also decrease the number of clinical trial sites and follow-up visits and potentially increase diversity and inclusivity in clinical trials7. For these and other advantageous reasons, we have seen the use of DHTs in clinical studies increase significantly over the years1,8,9,10. Recently, the first example of digital outcome assessment used in a pivotal study was completed, the Phase III REBUILD clinical trial of INOpulse for the treatment of fibrotic interstitial lung disease, the primary endpoint was the change in moderate to vigorous physical activity, as measured by actigraphy (NCT03267108). Unfortunately, the study failed to meet its primary endpoint.

Regulators and legislatures have recognized the potential of DHTs in clinical trials and provided guidance and documents to help support the development of these new tools3,5,6,11,12. As part of the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) work to fulfill the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) VII commitments, FDA has recently published the Framework for the Use of DHTs in Drug and Biological Product Development and established the DHT Steering Committee which consists of senior staff from the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), and the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) to support the implementation of the framework for the use of DHTs in drug and biological product development12,13. Additionally, the US FDA has created the Digital Health Center of Excellence, based in CDRH, which is intended to provide scientific expertise on DHTs for all of FDA and connect internal and external stakeholders to FDA in the DHT space. To further this mission, the US FDA created the Digital Health Advisory Committee in October 2023 to advise the Commissioner of Food and Drugs on scientific and technical issues related to DHTs. As part of the PDUFA VII commitments FDA has also agreed to hold a series of five public meetings to discuss the use of DHTs in regulatory decision making and identify three demonstration projects to further progress the evaluation of DHTs.

The recent landmark qualification of the stride velocity 95th centile as a primary endpoint for ambulatory Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy studies by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) demonstrates the regulatory utility of DHT-derived endpoints in drug development and approval processes14. This endpoint is also currently under review by the US FDA as part of the Drug Development Tools, Clinical Outcome Assessment (COA) qualification pathway15,16. In addition, US FDA qualified the first DHT under the Medical Device Development Tools program, as a biomarker to help evaluate estimates of atrial fibrillation burden as a secondary effectiveness endpoint within clinical studies intended to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of cardiac ablation devices17. This qualification is for a specific context of use (CoU) in medical device development and is not directly applicable to clinical studies for drug development in atrial fibrillation.

Regulatory acceptance of DHTs can be a rigorous and lengthy process. It necessitates results from multiple prospective studies to demonstrate the validity and reliability of DHT, and clinical relevance of the DHT-derived endpoint1,3,6,18,19.

While this manuscript focuses on the regulatory considerations of using DHTs for capturing COAs and biomarkers in clinical trials, it is crucial to consider other important aspects such as technical, operational, and ethical considerations. These topics are beyond the scope of this manuscript, but readers are referred to previous publications9,20,21.

Considerations for the use of DHTs in clinical trials

DHT-derived endpoints can complement accepted endpoints or provide new ways to capture existing endpoints for a more granular and holistic disease monitoring or awareness. If DHT is used for digital acquisition of an accepted endpoint (e.g., to measure blood pressure in a participant’s home), demonstration that DHT is fit-for-purpose (the level of validation associated with a DHT is sufficient to support its context of use3) is likely to be adequate for regulatory acceptance. If the DHT is a medical device, the clearance/approval of the DHT by FDA and/or CE marking under EU MDR for the intended purpose would be highly recommended to demonstrate that the device is fit-for-purpose. In many cases a DHT also measures a novel endpoint addressing unmet measurement needs in clinical development. In such cases, additional considerations as outlined in the following sections are required.

Concept of interest, context of use and conceptual framework

Incorporation of DHTs into a drug development program is a complex process. As outlined in Fig. 1, first, the Concept of Interest (CoI), a health experience that is meaningful to patients, and represents the intended benefit of treatment should be defined6,19,22. If the proposed measure is a novel endpoint, it would be advisable to establish early on whether the novel endpoint is addressing a core aspect of the disease and is meaningful to patients. Subsequently, the CoU should be delineated and include how the DHT will be used in the trial (i.e., endpoint hierarchy), the patient population, study design and whether the measure is a COA or a biomarker2,6,19,23 (Fig. 1).

Steps for showing DHT is fit for purpose for use in a development program as an endpoint measure.

It is important to design a conceptual framework for the DHT-derived endpoint visualizing the relevant experiences of patients, the targeted CoI, and how the proposed endpoint fits into the overall assessment in a clinical trial3. This becomes particularly important when the disease of interest has multiple health aspects, and the proposed endpoint does not address all of them. Figure 2 provides an example of a conceptual framework that outlines the different types of COAs proposed for each health concept of a disease and how a novel DHT-based electronic performance outcome assessment (ePerfO) fits within the model. In this example, the new ePerfO is proposed to be added to a traditional cognitive battery of tests to capture aspects of cognitive function that are not adequately captured in clinical trials for early Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). The Clinician Reported Outcome Assessment (ClinRO) and the Observer Rated Outcome Assessment (ObsRO) are validated measures. The ePerfO has multiple components and combining these individual components in validated machine learning-enabled models has been shown to enhance sensitivity in detecting cognitive impairment compared to traditional assessments in patients with mild cognitive impairment and dementia. A Type C meeting was requested seeking the FDA’s advice on the acceptability and validation of the ePerfO for demonstrating treatment effect on cognition in early AD (in 2022, under an investigational new drug (IND) application). The Agency provided feedback that it was unclear how the individual components of the ePerfO data would contribute to a meaningful assessment of cognition. The Agency communicated that even though the ePerfO might be a sensitive instrument for detecting subtle changes in cognition, there may be challenges in interpreting the clinical significance of any effects of an intervention on that instrument. The Agency recommended to consider the ePerfO to be most appropriate only as an exploratory endpoint. The Agency did not comment on the proposed ClinRO and ObsRO.

The framework outlines the relevant experiences of patients related to meaningful health concepts in AD and corresponding CoI within the Conceptual Model. Measurement Model then links each CoI to a COA assessing the severity or impact of the corresponding aspect of the disease. ePerfO (Electronic Performance Outcome Assessment) is a novel ePerfO measured by a DHT; *: ClinRO (Clinician Reported Outcome Assessment) and ObsRO (Observer Rated Outcome Assessment) are broadly used and validated outcome assessments.

This feedback highlights the importance of demonstration of the meaningfulness of the new measures to the patients. However, establishing clinical meaningfulness for abstract concepts, such as cognitive domains (e.g., executive functioning, processing speed) represents challenges. Additionally, in diseases with cognitive impairment like AD, patients often suffer from a lack of insight, making it difficult to rely solely on their self-reported assessments. Instead, care partner input is often used, but it is subjective and may not accurately reflect how patients truly feel and function. Moreover, in AD, when treatments are directed towards slowing cognitive decline, it can be difficult to demonstrate the meaningfulness of the change when improvement is seen in the form of slowed decline. As such, the assessment of the meaningfulness of the treatment effect on cognitive decline in early AD remains an unresolved issue. Early HA consultations are advisable to ensure that the endpoint is accepted by the HAs (also see Figs. 3 and 4).

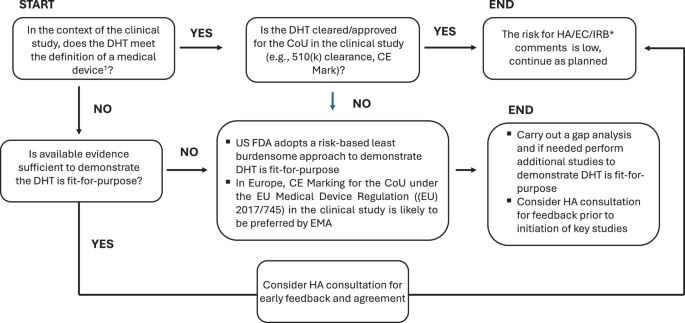

1: The definition of medical devices is provided in Section 201(h) of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and Regulation in the US and (EU) 2017/745 (Medical Devices Regulation) and Regulation (EU) 2017/746 in Europe. *: In cases where DHT is a medical device, CE marking is provided by a Notified Body (NB); HA: Health Authority; IRB: Institutional Review Body, EC: Ethics Committee.

The key time points for HA consultations include prior to starting clinical studies to align on CoI and CoU and prior to progressing from early exploratory studies to registrational studies to align on whether the evidence package would support method finalization.

Fit-for-purpose/ fit-for-the intended use

After defining the CoI and CoU, the minimum technical and performance specifications of the prospective DHT should be established to guide selection of a fit-for-purpose DHT (Fig. 1). These specifications could also be used as reference to ensure the DHT remains fit-for-purpose for the duration of the trial3. Further information on the DHT can be obtained from the manufacturer(s)/vendor(s) directly (Table 1).

The DHT must be fit-for-purpose/ fit-for-the intended use. The evidentiary burden to demonstrate the DHT is fit-for-purpose for regulatory acceptance varies depending on how the DHT is used18,19. The highest bar will be for use as a primary endpoint or to support label claims in a pivotal trial. For all DHTs regardless of whether they are medical devices or consumer grade, it is recommended to review the technical specifications, available verification, and validation information even if the DHT will be for use in an exploratory endpoint for internal decision making and/or hypothesis generation.

Figure 3 describes a decision tree based on whether the DHT is a medical device, whether it is fit-for-purpose for the intended use and recommended HA consultations. The intended use and indications for use of the DHT determine whether it meets the definition of a medical device. In the US, FDA adopts a risk-based least burdensome approach for DHTs that are medical devices but are not cleared or approved for the proposed intended use: for a non-significant risk device (21 CFR 812.3(m)) an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) application to FDA is not generally required if the investigation complies with the abbreviated requirements in 21 CFR 812.2(b); for a significant risk device, when all information required in an IDE application under 21CFR 812.20 is provided in the IND, a separate IDE submission is unlikely to be needed3. The regulatory and legal framework for DHTs in Europe differs from that of the US4,6,11. EMA’s remit is limited to the specific use of a methodology in the development, use or monitoring of medicinal products pre- or post-authorization4,6. EMA and National Competent Authorities (NCAs, the medicines regulatory authorities of the Member States that are primarily responsible for the authorization of medicines available in the EU that do not pass through the centralized procedure) in Europe are likely to expect the technical validity of DHTs to be demonstrated, ideally through CE marking for the intended COU in the trial. The DHT should be deemed “suitable and valid” and supporting data should be presented in the in the Marketing Authorization Application (MAA)14,24.

In Europe, the responsibility for assessing medical device submissions and granting CE marks lies with Notified Bodies (NBs, an organization designated by an EU country to assess the conformity of certain products before being placed on the market). NBs, however, do not participate in drug medicinal product review or provide advice on device development unless the sponsor submits an application to the NB for the device approval. Additionally, in Europe, not all NCAs have medical device expertise, thus when technical information for DHTs is submitted to NCAs for review, differences in opinions among NCAs may arise. This can create a bottleneck for the use of DHTs that are not CE marked under Medical Device Regulation ((EU) 2017/745) for the intended use but are deemed fit-for-purpose. In the Regulatory Science Strategy to 2025, EMA recognized the potential impact of DHTs on drug development and committed to establishing a multi-stakeholder platform to gather feedback on the use of DHT-derived measures and endpoints5. This new platform is aimed to complement the existing qualification and scientific advice procedures and provide an additional avenue for obtaining input from various stakeholders, including NBs. By bringing together relevant competencies and expertise, the platform is expected to streamline the regulatory evaluation of DHTs while minimizing unnecessary delays. It is not yet clear how the new platform could help to streamline advice from NCAs that have different opinions or how the existing bottlenecks for non-CE marked DHTs could be addressed. It is encouraging, however, that proposals for new EU/EEA pharmaceutical legislation includes provisions for the EMA to use device expertise when developers are seeking scientific advice for medicinal products to be used with a device.

Changes to the DHTs during the clinical trials

Changes to the DHTs such as software or hardware updates during the clinical trials, could occur for various reasons (e.g., to implement improvements that enhance the patient’s experience or add new features to the device etc.). Sponsor may be forced to consider changing the DHT while the study is ongoing due to issues with the supplier. These changes could have significant implications, up to the invalidation of results from a clinical study. Ideally, the ability to freeze the algorithm prior to the start of the study should be one of the minimum technical requirements as part of the DHT fit-for-purpose assessment.

For medical devices it is expected that the manufacturers have change-control plans. For consumer grade technologies, these changes and their timing are likely to be driven by market needs. It would be advisable to collaborate with the manufacturers to address the potential mismatch between market needs and clinical trial use by establishing a predetermined change-control plan whereby intended modifications to the technologies are proactively specified. Contingency plans should be put in place to address planned and unplanned changes to minimize the impact on the ongoing study. Sponsors are recommended to put a risk mitigation plan around this in advance. When changes occur, the sponsors should assess the change and its implications (e.g., whether the data obtained by different versions are significant, whether the changes result in data integrity or safety issues) and document it as part of the audit trail system. Additional verification and validation studies may be required3,11.

Considerations for missing data

Missing data and how it is minimized is an important aspect of DHT-based measures as it may occur during remote data acquisition. During the DHT development or selection of a DHT for use in a clinical trial, the design features of DHTs such as data storage capacity, battery life as well as trial design and operational aspects (e.g., patient population, timing, frequency and duration of data collection, and suitability of the data acquisition and transfer methods) should be considered to minimize missing data. Sponsors should also ensure that site personnel, study participants and their care providers are adequately trained. However, despite all efforts, the missing data is unlikely to be fully eliminated. How much missing data can be tolerated would depend on the purpose of the DHT-driven measure in the study. Sponsors should have a plan in place to reduce the potential for missing data as part of the risk management plan. How to handle missing data should be discussed and aligned with regulators early on3.

Data protection and privacy

Clinical trial sponsors need to ensure transparency, lawful collection, transfer and retaining of the minimum required personal information, to be used for the purposes specifically communicated to clinical trial participants. Following the applicable laws and regulations (e.g., General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU25), this could be achieved through less intrusive ways, ensuring sufficient information is provided to the participants allowing them to make informed decisions. Prior to implementation of a DHT, a privacy assessment should be done to assess risks and potential harm to the individuals and third parties involved in data collection. This assessment should include cybersecurity requirements. Adequate data transfer measures including measures for the transfer of personal data to a third country or to an international organization according to Chapter 5 of GDPR25 should also be in place3,11.

Additional considerations for measuring a novel endpoint

When the DHT is measuring a novel endpoint, in addition to demonstrating that it is fit-for-purpose, a strong justification on how the new measure adds value compared to existing measures is needed3. Principles around the development of novel DHT-derived endpoints are the same as those for any other endpoint development3. Early in the development process, it is crucial to define whether the new measure is a COA or a biomarker, as part of COU delineation26. This distinction is important because it can influence the evidentiary requirements for its acceptance by regulators. The authors strongly recommend against considering a COA as a biomarker (and against the interchangeable use of those terms), even for internal decision making. Also note that the type of the biomarker and how it is used in the trial would also influence the evidence requirements for its acceptance27. A novel biomarker must be demonstrated to be accurate (i.e., analytically validated). There should be a discussion with the HAs as to what level of accuracy is necessary for the novel biomarker prior to the initiation of an analytical validation study. In the US, for biomarkers used as surrogate endpoints for accelerated approval the sponsor must demonstrate that the surrogate is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit28,29,30,31.

Sponsors should provide a robust rationale for developing the new endpoint. For instance, the novel digital endpoint (i) could be more sensitive and accurate than existing endpoints, (ii) can directly measure the patient’s disease symptoms rather than a distal concept of the disease. In disease areas where there is clearly an unmet need for new endpoints, HAs may take a risk based approach to the benefit:risk assessment for use of novel digital endpoints. For more details on endpoint development including demonstration of clinical meaningfulness and applicable statistical approaches readers are referred to FDA publications18,19,27.

Health authority submissions and consultations

Discussions with HAs should begin early, before beginning clinical studies to gain agreement on the COI, path towards validation of the DHT and endpoint (Fig. 4). At this early stage during the conceptualization of the COI and COU, if relevant data from literature and the DHT manufacturer are available, those should be presented to the HAs.

There are multiple ways to engage with HAs to receive feedback on the desired endpoint and/or the DHT being developed, depending on the goal of the development program. FDA and EMA have voluntary qualification processes for drug development tools (DDTs) and methodologies, which provide options to obtain advice and qualification of a specific context of use of the proposed method in a clinical trial context (Table 2). Qualification as a DDT is not mandatory and requires a comprehensive evidentiary package with certain aspects of submissions being publicly disclosed. Once a DDT is qualified, it can be utilized for the development of any product for the qualified COU. However, to date there have been no successful DDT qualifications for DHTs to be used in drug development clinical trials in the US. The “cost, complexity, and multidisciplinary nature” of qualification may create challenges for individual stakeholders23. Instead, qualification programs are encouraged to be used by collaborative entities, such as consortiums or other public-private partnerships. Innovative Science and Technology Approaches for New Drugs (ISTAND) pilot program is an exciting new opportunity for DHTs to be qualified by the FDA and may be suitable for qualification of DDTs that are out of scope for existing DDT qualification programs but may still be beneficial for drug development23. For DHT use in individual drug development programs, use of HAs’ scientific advice meetings provides sponsors with more targeted, and confidential sources of advice and guidance (Table 2)13,32,33.

It is important to plan for multiple engagements with HAs to allow for the implementation of the feedback received into the study design and set up follow-up meetings to discuss results and determine next steps. Because HA consultations are resource intensive, sufficient resources should be allocated as part of the program plans and objectives. Engaging with HAs and incorporating their feedback into the study design increases the likelihood of ultimate regulatory acceptance and facilitates smooth implementation of DHT-derived endpoints in clinical studies. Since these technologies will support global projects, it is essential to consult major HAs, such as the EMA, US FDA, UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), or Japan Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), to ensure alignment with regulatory requirements across different regions and to obtain broader acceptance. Differences in requirements for validation of DHT-based measures from different HAs could delay and in some cases prevent the successful implementation of these measures. Harmonization of requirements for validation/qualification of DHT-based measures by achieving scientific consensus with regulatory and industry experts and other stakeholders is key to advance the field.

In summary, successful integration of DHT-derived endpoints requires a comprehensive regulatory strategy as part of an overall development plan. This strategy should be tailored to the specific program objectives, endpoint hierarchy, target product profile and include planning for global HA consultations. Engaging with HAs early on allows alignment with regulatory requirements, identification of potential gaps and implementation of strategies to address them effectively in a timely manner.

Responses