Biomolecule sensors based on organic electrochemical transistors

Introduction

Biomolecules are essential for the function and structure of living organisms1. Various types of biomolecules, such as glucose2,3,4, dopamine (DA)5,6,7, lactate (LA)8,9,10, DNA11,12,13, protein14,15,16, etc., play crucial roles in physiological processes and are essential for health maintaining. For example, glucose concentration in blood directly relates to the blood sugar level, energy provision, and metabolism in the human body17. While proteins are the main carriers of life processes, which can promote physiological regulation, repair, and renewal of damaged cells, and provide energy for human life activities18. Therefore, precise and real-time detection of biomolecule concentration levels can offer essential data for monitoring health status19.

Electrochemical sensors for the detection of biomolecules stand out among numerous detection techniques due to their advantages in high sensitivity, selectivity, and portability. Traditional electrochemical sensors are typically based on functional sensing working electrodes, which show enormous capability for various biomolecular sensing20,21. In recent years, the requirement for accurate biomolecule detection and monitoring has propelled the development of electrochemical sensor platforms to transistor-based sensors22. Since the invention of transistors in 194723, rapid development and wide applications in various electronics have been realized. In addition to their fundamental applications in integrated circuits, transistors have been applied for the detection of biomolecules due to their capability to sense and amplify the sensing signals, simultaneously24. Especially, after the invention of organic field-effect transistors (OFETs) by Tsumura et al. in 198625, Goetz et al. successfully applied them to biosensing26. Due to their high sensitivity and ease of integration, OFETs are now widely used in many fields such as biomedicine, bionic skin, etc., due to their mechanical flexibility, ease of bio functionality, and potential for low cost24. Similar to OFETs, OECTs, which depend on the electrochemical doping/dedoping of the channel materials by the injection/extraction of ions from the electrolyte-based dielectric, are also promising candidates for high-performance biosensors due to high transconductance (gm > 10 mS), low driving voltage (<1 V), and biocompatibility27,28,29,30. Especially, the versatile device structures of OECTs enable them for a wide variety of chemical and biomolecule sensing31,32.

Even though invented by Wrighton et al. in the mid-1980s33, only in recent years, OECTs have become the research highlight in the realm of sensing for biomolecules and have made significant advancements for various biomolecules with high current sensitivity (SI). Previous reviews on OECTs focused on organic mixed ion-electronic conductors (OMIECs)34,35, operating principle and device physics24,36, electrolyte dielectric components37, application in biological sensing38 and microelectronics39, as well as wearable/implantable OECTs for biosensing applications20,27,28,40,41, were reported. While a detailed and systematic overview focusing on recent progress made by OECTs in biomolecule detection (including the newest detection techniques, and methods to improve the sensitivity of detection limits) is still missing.

This review highlights the progress of biomolecule sensors based on OECTs, with a focus on research published in the past 5 years. First, the working principle and sensing mechanism of OECTs are systematically described. Specifically, various OECTs-based biosensors, including small biomolecules (such as glucose2,3,4, DA5,6,7, LA8,9,10) and biomacromolecules (such as DNA11,12,42, protein14,15,16), are classified and introduced according to their structural design and detection mechanism. Additionally, emerging technologies (including circuits, microfluidic channels, artificial intelligence (AI)/machine learning (ML) applied along with OECTs, etc.) and materials (including materials for gate modification, OMIECs, and electrolyte functionalization) used to enhance sensitivity, detection limit, and range of detection, are also summarized. Last, directions of OECT-based biosensors for future development are proposed. This review is expected to provide theoretical support and design hints for the application of OECT-based biosensors.

Structure and operating mechanism based on OECTs

Structure and working mechanism of OECTs

A typical OECT comprises three electrodes (gate, source, and drain), a transistor channel comprised of an OMIEC, and an electrolyte (Fig. 1a). The gate electrode can be made by a polarizable electrode (such as gold (Au), or platinum (Pt)), or by a non-polarizable electrode (Ag/AgCl), while the source and drain electrodes are typically conductors with electrochemical inert properties (such as Au). The channel material is in direct contact with the electrolyte, which enables the injection/extraction of ions from the electrolyte to the channel under the voltage bias of the gate electrode. Note that OECTs operating in enhancement mode are preferred, as they are normally OFF at a gate voltage (VG) bias of 0 V. In enhancement-mode p-type OECTs, a negative VG bias results in anions injection into the channel with concomitant doping (oxidation) of the polymer leading to enhanced drain current (ID) (ON state). In n-type OECTs, when a positive VG bias is applied, cations are injected into the channel, resulting in an increased ID24,28,43. Representative transfer (ID against VG under a constant drain voltage (VD)) and output characteristics (ID against VD under stepwise constant VG) of both p- and n-type OECTs are demonstrated in Fig. 1b and c, respectively.

a Typical structure of an OECT. b Typical transfer and c output curves of P-type OECTs and N-type OECTs. Electronic circuit and ionic circuit of OECTs with d nonpolarizable gate electrode and e polarizable gate electrode. f Potential distribution in the ionic circuit of OECTs.

Currently, Bernards model44 is the most widely used model to describe the working mechanism of OECTs. It is described that when a voltage bias is applied between the source and drain electrodes, ID is generated, which represents the current that passes through the active channel. The magnitude of this current is modulated by the VG bias, which controls the doping level of the channel by modulating the injection or extraction of ions into the channel, thereby changing the channel conductivity27. To more accurately model the behavior of OECTs, Bernards et al. equated OECTs with a combination of an electronic circuit and an ionic circuit44. The electronic circuit, which is mainly composed of the source, the drain, and the channel, can be treated as a resistor. The ionic circuit, for OECTs with non-polarizable gates (Fig. 1d), consists of a resistor (RE) and a capacitor (Cd) in series, which represent the resistance in the electrolyte and the capacitance between electrolyte and channel, respectively; while for OECTs with polarizable gates (Fig. 1e), a capacitor (CG) represents the capacitance between the gate electrode and electrolyte needs to be added. Therefore, when using a polarizable gate electrode (e.g., Pt or Au), to enable effective gating, CG should be much larger than the channel capacitance (CCH) (Fig. 1f). Consequently, an oversized gate is typically required in this case, which is not conducive to device integration. On the other hand, for nonpolarized gate electrodes (e.g., Ag/AgCl or a thick poly(styrene sulfonate)-doped poly(3,4‑ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT:PSS film)), as the CG can be considered to be extremely large, therefore it is usually neglected in the model, and enable smaller footprint of the gate27,28.

The main performance metric of OECTs is gm, defined as the first derivative of the transfer curve (∂ID/∂VG), which represents the transit efficiency of a small voltage signal on the effective gate bias to a large current signal in the channel, and can be expressed by the following equations28,29,44:

where W, L, and d are the channel width, length, and thickness, respectively. μ represents the charge carrier mobility, C* denotes the channel capacitance per unit volume, and VT is the threshold voltage. Since gm is directly correlated to SI and the detection limit of OECTs, constructing OECTs with higher gm is an obvious and effective way to enable high-performance sensors.

Biosensing mechanisms of OECTs

As shown in Fig. 2, there are mainly three strategies to enable the biomolecule sensing capability of OECTs: 1) Gate functionalization (Fig. 2a). The gate electrode of OECTs can be functionalized to serve as a recognition site of bio-analytes, where electrons generated by redox reactions or capacitance variations due to selective binding on the functional gate surface can result in a variation in the effective gate potential27,41. Therefore, gate modification is an effective and conventional strategy for realizing OECT-based biosensors. 2) Channel-electrolyte interface functionalization (Fig. 2b). The target analyte could react with the transistor channel due to functional modification of the channel surface or channel bulk, resulting in a change in the electronic structure of the channel or voltage drop at the electrolyte/channel interface, thereby affecting the channel conductivity45. 3) Electrolyte functionalization (Fig. 2c). By integrating enzymes46,47, ion-selective membranes48,49, or suspended cells50, the electrolytes of OECTs can be functionalized for biosensing applications.

a Gate functionalization. b Channel-electrolyte interface functionalization. c Electrolyte functionalization.

In all cases, OECT-based biosensors are capable of converting biological signals of the analyte to electrical signals, wherein the effective gate voltage (VeffG) or the doping state of the channel will change as the concentration of the analyte changes, allowing sensing to be achieved by shifting in the transfer curves and changing ID under certain VG41.

OECT-based biomolecule sensors

Depending on the molecular weight, biomolecule sensors based on OECTs can be classified into biomolecule sensors of small biomolecules (e.g., glucose, DA, LA, etc.) and large biomolecules (e.g., DNA, RNA, proteins, etc.). In addition, detection mechanisms are typically different: for small molecule sensing, they are usually detected by reacting with specific receptors or enzymes, resulting in changes in ion transport or electron transfer. For macromolecule sensing, they often require specific recognition molecules (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) for capture and recognition. Therefore, considering the distinct molecular characteristics, sensing mechanisms, and detection requirements, this chapter will be divided into biosensors for small molecule and macromolecule sensors, respectively.

OECTs for small molecule detection

Biological small molecules are usually organic compounds with relatively small molecular weights (generally less than 900 Daltons) in living organisms, and these compounds play important functions and roles in life activities51. Assays based on small biological molecules, such as glucose, DA, LA, etc., provide profound insights that can reveal aspects of health in human body fluids. This section summarizes recent advances in OECT-based small molecule biosensors and categorizes them depending on different sensing targets.

Glucose detection

As one of the main energy sources of the human body, glucose is essential for maintaining normal physiological function and health status. Besides, accurate and real-time detection of glucose levels is a critical step in diagnosing diabetes52. OECTs are widely used for glucose detection due to their inherent advantages in biosensing. Typically, glucose oxidase (GOx) is first functionalized on the gate electrode. When the electrolyte containing glucose is in contact with the functional gate electrode, glucose is oxidized to gluconolactone and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Subsequently, H2O2 is further oxidized, and the VeffG will be affected, which results in a corresponding ID change. The sensing mechanism of the OECT-based glucose sensor can be explained by the following reactions53,54:

Therefore, the glucose concentration can be determined by assessing the alterations in VeffG or ID. Based on the detection mechanism of glucose, gate functionalization is one of the most widely used methods for OECT-based glucose sensors.

In practical glucose analysis, several electroactive compounds, such as ascorbic acid (AA) and uric acid (UA), are the main interferences in determining glucose55. Since Nafion is negatively charged in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution, it could effectively reduce the interference from other substances in negatively charged states through electrostatic interaction. Additionally, Nafion holds the capability to boost gate surface reactions, foster reactivity, and stabilize electrodes56. Hence, Nafion, with its optimal biocompatibility for biosensor development, is frequently paired with GOx to modify gates for glucose detection57,58,59.

For example, a thick-film approach for developing OECTs on paper substrates showed outstanding sensing performance. Such devices displayed a high gm exceeding 40 mS and an on/off current ratio of 3.8 × 103. After functioning the gate with GOx and Nafion, the OECTs showed an SI of 1.72 mA/decade and a detection limit of 0.1 mM towards glucose57. On the other hand, Ren and co-workers fabricated an all-carbon OECT with laser-induced graphene (LIG) as the electrodes2. The device achieves a high normalized gm of 30.1 ± 3.2 S cm−1 benefiting from the porous LIG surface (Note, normalized gm is based on the equation of gm,norm = gm/(Wd/L)60). For glucose sensing, platinum nanoparticles (PtNPs) were coated on the gate surface, and then further decorated with a mixture of GOx, Nafion, and chitosan (as an adhesive to immobilize the GOx on the gate electrode). Here, PtNPs serve as a pivotal catalyst for the oxidation of H2O2, thereby enhancing the sensitivity of OECT-based glucose sensors2,55,61,62,63. Then, quantitative detection of glucose in artificial sweat and human skin was enabled. Diacci and colleagues reported OECTs capable of real-time monitoring of chloroplast glucose output in two different metabolic phases (Fig. 3a)62. Effective glucose detection was achieved by electrodepositing PtNPs and modifying GOx and chitosan on the gates (Fig. 3b), leading to rapid real-time measurement (a temporal resolution of 1 min) of glucose levels from isolated chloroplasts (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, using the same gate modification method, the group developed OECTs for real-time in vivo monitoring of glucose (100 μM-1 mM) in tree vascular tissues63. This work also produced a simple portable assay that can be used directly for real-time measurements under complex plant growth conditions. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 3d-f, Ji et al. utilized a bias-free two-step dip-coating method to deposit PtNPs on the gate electrode of OECTs55. To further enhance accuracy and efficiency, OECTs are combined with microfluidics and a driving circuit that can wirelessly connect to a smartphone. A portable glucose sensor was presented, in which the gates were modified with GOx/chitosan/Nafion for real-time glucose detection in human saliva and is expected to be a promising means for in-home health monitoring.

a Chloroplasts alternate starch production during the day for storage and degradation at night for glucose release. b Structure of gate electrode functionalized with GOx/chitosan/PtNPs. c Normalized response of the OECT functionalized with GOx, to increasing glucose concentrations in PBS buffer (black), chloroplast isolation buffer (CIB) (blue), and inactive chloroplast solution (green). a–c Reproduced with permission62. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH. d Gate modification with PtNPs/GOx/chitosan/Nafion. e Schematic diagram of the interaction with a microfluidic channel and a smartphone, and f normalized ID versus times curves after injection of different concentrations of pure glucose solution. d–f Reproduced with permission55. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH. g OECT-based glucose sensor configuration with the PEDOT-PBA functionalized Au gate electrode. NR of the OECT gated with h NIP electrode and i MIP electrode when exposed to various glucose concentrations. g–i Reproduced with permission64. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH.

To further enhance the sensitivity of OECTs towards glucose, Li et al. presented a plasmonic OECT (POET)54, where the nanostructured gate electrode of POET is exposed to light to generate a plasmonic field. Then the gate was modified by adding a mixture of GOx and chitosan for glucose detection. Consequently, the plasmonic heating accelerates the oxidation of H2O2, which further alters the VeffG of the POET, and thus achieves higher performance for glucose detection, where a 5-fold increase in SI is achieved when compared to conventional OECTs. In contrast to conventional enzymatic sensors, Kousseff and colleagues proposed a non-enzymatic glucose detection method by employing a newly synthesized functionalized monomer, EDOT-PBA64. By optimizing electrodeposition conditions, two polymer film structures were developed: pristine PEDOT-PBA and molecularly imprinted PEDOT-PBA, both demonstrating excellent glucose binding and signal transduction. An OECT-based glucose sensor was successfully fabricated using Au gates functionalized with these two distinct polymer structures (Fig. 3g). The formation of the PBA-glucose complex at the gate electrode modifies the gate capacitance, leading to changes in the ID. As shown in Fig. 3h, i, such an OECT based on a non-imprinted polymer (NIP) gate shows a good linear response over a range of glucose concentrations from 10 μM to 100 μM and 100 μM to 10 mM. The molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) gate-based OECT exhibited a single linear response within a broad range of glucose concentrations (10 μM to 10 mM). This sensing platform has the potential for further development into miniaturized and integrated sensors. Note, the normalized response (NR) shown in Fig. 3h-i is extracted by the following equation:

where I0 is the baseline current when no analyte was added and Ianalyte is the current obtained upon the injection of different analyte concentrations. Overall, these studies have effectively enhanced glucose sensing by optimizing detection performance, particularly through gate functionalization, which has proven crucial for improving sensor sensitivity and reliability.

Based on the definition of SI:

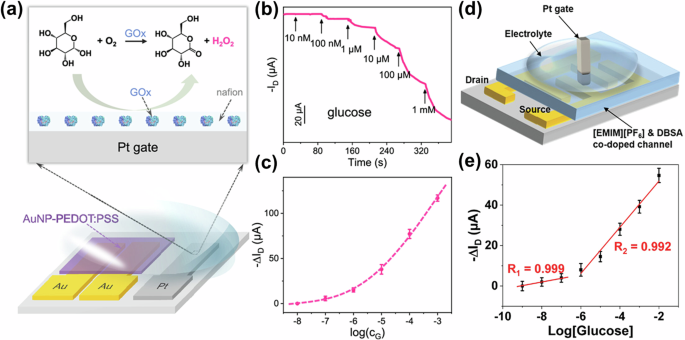

where c is ion concentration. It is obvious that higher gm leads to higher SI. Thus, researchers have been focused on developing novel OMIECs to enhance gm. As shown in Fig. 4a, to enable higher gm, Zhang et al. doped the PEDOT:PSS film with plasmonic gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) as the channel layer using a solution-based process, followed by photo-annealing58. This process effectively enhances gm to 14.9 mS when compared to the original value of 1.9 mS. By applying the gate with GOx and Nafion modification, efficient detection of glucose concentrations from 10 nM to 1 mM was achieved by monitoring ID variations under a constant gate bias (Fig. 4b, c).

a Diagram of OECT-based glucose sensor and demonstration of the sensing gate reaction. b Variations of ID versus time at different glucose concentrations and c response relationship of ΔID versus logarithm of glucose concentration (CG). a–c Reproduced with permission58. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. d Schematic structure and e the relative change in ID versus the concentration of glucose of an OECT with Pt gates for interpolated electrodes. Reproduced with permission59. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH.

In another work from the same group, by introducing Nafion in the channel65, a significant enhancement on the gm (up to 10-fold and 4-fold in PEDOT:PSS and poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) based channel, respectively) was achieved, resulting in the successful preparation of a high-performance OECT glucose sensor with a lower detection limit of 10 pM. Similarly, as illustrated in Fig. 4d, by introducing an ionic liquid 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate ([EMIM][PF6]) and dodecylbenzene sulfonate (DBSA) in PEDOT:PSS, along with the utilization of interdigitated electrodes as the source and drain electrodes, Wang et al. achieved OECTs with ultra-high peak gm of 180 mS59. Note, here the Pt gate electrode was modified with Nafion/GOx, which could be used for the ultra-sensitive detection of glucose based on the enzymatic reaction. The relative change in ID (ΔID) versus glucose concentration shows a good linear response in the range of 1−100 nM and 1 μM–10 mM, respectively (Fig. 4e).

P-type OECTs are relatively well developed and widely used due to their high gm and electrochemical stability58,66. In contrast, fewer reports on high-performance n-type OECTs have been demonstrated67,68. Note, that n-type OECTs should be more suitable for enzyme-based sensing since they can accept electrons generated during enzymatic reactions and act as a series of redox centers capable of switching between neutral and reduced states. Therefore, n-type OECTs typically exhibit higher performance due to their ability to stabilize electrons by direct electron transport in the channel10,67. Furthermore, with both high-performance p- and n-type OECTs, the construction of complementary logic circuits can be facilitated, which could be beneficial for integrated low-power bioelectronics and biosensors69. Based on this, Savva et al. proposed a simple solvent engineering approach to fabricate high-performance n-type OECTs70. Adding acetone into an n-type polymer P-90 solution (Here P-90 refers to the random copolymer of N,N’-bis(7-glycol)-naphthalene-1,4,5,8bis(dicarboximide), N,N’-bis (2-octyldodecyl)-naphthalene-1,4,5,8bis(dicarboximide) and bithiophene) leads to a 3-fold increase of the gm, attributed to the simultaneous augmentation of volumetric capacitance and electron mobility within the channel. As the interaction between the enzyme and P-90 brings the protein close to the film, the electrons generated during the enzymatic reaction are transferred to the conjugated polymer. For glucose sensing, the active regions (channel and gate) were coated with P-90 polymer and then incubated with GOx. This glucose sensor achieved a detection limit as low as 10 nM and a dynamic range of more than 8 orders of magnitude. Similarly, Koklu and co-workers fabricated n-type OECTs by immobilizing GOx on P-9071, patterned at the channel and gate electrode, along with the integration of a microfluidic system for real-time glucose detection, which achieved a detection limit as low as 1 nM. Zhou et al. also prepared an n-type OECT-based glucose sensor by using a polymer poly(benzimidazobenzophenanthroline) (BBL) as the active layer (Fig. 5a)72, which exhibits high performance and stability, rendering it a promising candidate for glucose sensing. As depicted in Fig. 5b, with GOx/chitosan immobilized on the gate electrode, such OECTs exhibited poor sensitivity to glucose, which suggests that gold acts as a poor electron acceptor when oxygen and peroxide are involved in the cycle. However, the introduction of ferrocene as an electronic mediator on the gate can facilitate efficient electron transfer to gold, resulting in OECT sensors with a good linear response and an SI of 0.58 μA/mM within glucose concentration range from 0.6 mM to 30 mM (Fig. 5c).

a Schematic diagram of an OECT-based glucose sensor, modified gate electrode, and polymer structure of BBL. b Output current of OECTs with continuous adding glucose solution (GOx/chitosan is deposited on gate electrode). c Corresponding calibration plot in the linear range of OECTs with continuous adding glucose solution (GOx/chitosan/ferrocene is deposited on gate electrode). a–c Reproduced with permission72. Copyright 2024, Elsevier. d Glucose sensor based on hPDI[3]-based OECTs. e Cycling stability of the OECT with 100 switching cycles between 0 and 0.5 V. f Transfer characteristics and variation of ID (inset) with different glucose concentrations of the glucose sensor. d–f Reproduced with permission73. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH.

To further enhance the performance of n-type OECTs, Wu et al. designed two new n-type polymers (f-BTI2g-SVSCN and f-BSeI2g-SVSCN) with different selenophene contents60. The OECT prepared from f-BSeI2g-SVSCN with the highest selenophene content achieved a high normalized gm of 71.4 S cm−1 and a record-breaking μC* of 191.2 F cm−1 V−1 s−1. By using polyaniline (PANI)/PtNPs/GOx to modify the Pt gate, a glucose sensor with a low detection limit of 10 nM was further implemented, demonstrating the potential of selenophene substitution strategy for n-type OECT in biosensing applications. Likewise, in Fig. 5d–f, Nguyen-Dang et al. reported a solution-processable semiconductor helical perylene diimide trimer (hPDI[3]) for n-type OECTs73, which showed a gm of 44 mS and excellent long-term storage stability (>5 weeks). Such good performance rendered it highly appropriate for practical biosensing. Thus, an hPDI[3]-based OECT as a glucose sensor was fabricated, demonstrating good performance in the detection range of 0.01–31 mM, which illustrates its n-type nature, stability in aqueous solutions, and broad applicability. Thus, through the continuous design and optimization of OMIECs, particularly n-type semiconductor materials, the gm of OECTs can be significantly enhanced, thereby improving the sensitivity and performance of glucose detection.

Moreover, many researchers have demonstrated OECT-based glucose sensors with flexibility or stretchability, which provide a comfortable bioelectronic interface for glucose detection in living organisms or for wearable scenarios. For instance, a coaxial fiber OECT with a micron-sized channel length was developed, achieving an ultra-high gm of 135 mS (Fig. 6a–e)74. The device shows highly stable gm, on current and on/off current ratios after being treated with different bending radii from 10 to 1.5 mm, various bending/friction cycles, and soaking in artificial cerebrospinal fluid. By further modifying the carbon nanotube (CNT) gate with tetrathiafulvalene (TTF) as an electron transfer agent and GOx as a glucose-sensitive catalyst, an SI of 3.78 mA/decade, a detection limit of 20 μM, and a linear range of 0.04 to 0.7 mM for glucose detection were achieved. Qing et al. developed an all-fiber OECT-based glucose sensor enabled by thermoelectric fabrics (TEFs)75. Both OECTs and TEFs are constructed using yarns composed of cotton, PEDOT:PSS, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), (3-glycidoxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GOPS), collectively referred to as PDG yarns. The device demonstrated a linear monitoring range for glucose in artificial sweat, with a sensitivity of 30.4 normalized current response (NCR)/decade within the detection range from 10 nM to 50 μM. It exhibited reliable stability and anti-interference properties, along with a high degree of precision and accuracy. Similarly, fiber-based OECTs were used as glucose sensors by modifying the Pt gates with composites of GOx, chitosan, and graphene flakes, achieving a glucose detection limit as low as 30 nM76. In addition, a novel method to fabricate stretchable OECTs based on bionic polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrates with up to 30% omnidirectional stretch was reported (Fig. 6f-h)77. Upon integration with the GOx-modified gates, the system exhibited an exceptional glucose detection limit of 1 μM, markedly exceeding the minimal glucose threshold present in bodily fluids. These wearable OECT-based glucose sensors hold significant promise for non-invasive and continuous glucose monitoring, offering a convenient and reliable solution for personalized healthcare and diabetes management.

a Schematic illustration of coaxial fiber OECT. b Relative change in ID and linear fitting curve in function of glucose concentration. Normalized gm and on-state current stabilities of coaxial fiber OECTs under (c) bending, d friction, and e soaking. a–e Reproduced with permission74. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature. f Photographs and g transfer curves under 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30% strains of a stretchable OECT as attachable devices. h ID versus times of the addition glucose concentrations. f–h Reproduced with permission77. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH.

Recently, there has been a growing trend to develop OECT-based biodegradable/biocompatible glucose sensors for biomedical and eco-friendly applications. For example, Clarifoil substrates based on cellulose acetate films, are suitable for biosensing applications due to their biocompatibility and degradability. Thus an OECT for the selective glucose detection by using printed carbon-based nanocomposites as electrodes (for source, drain, and gate electrodes) on Clarifoil substrates was presented78. By exposing the sensor in direct contact with the electrolyte solution prepared by mixing PBS and GOx, a significant response to glucose concentration in the range of 1 μM–100 mM was demonstrated. Similarly, Fumeaux and colleagues presented OECTs with degradable electrodes, which were printed on eco- and bioresorbable polylactic acid (PLA) substrates (Fig. 7a)79. Qualitative assessment of device degradation testing at different time points (pristine, 3 weeks, and 4 weeks) was demonstrated (Fig. 7b), where the PLA substrate and the carbon contacts have undergone obvious degradation after 4 weeks. Additionally, the PEDOT:PSS channel has exhibited significant deterioration, with a considerable portion of it having broken down entirely. The sensing capabilities of such OECT-based transient biosensors are demonstrated through enzyme-based detection of glucose, with a detection limit of about 5 μM and a sensitivity of 3.4 ± 0.6%/decade. Furthermore, Wang et al. developed highly elastic, durable, and recyclable all‑Polymer OECTs80. Microstructures of doped PEDOT:PSS with lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) were transfer printed onto a resilient gelatin-based electrolyte, enabling the rapid prototyping of these devices. Biodegradable gelatin combined with self-crosslinking PEDOT:PSS/LiTFSI provides excellent stability, allowing for on-demand disposal and recycling. In addition, by modifying the gate interface with immobilized GOx in the gelatin electrolyte, successful detection of glucose at concentrations as low as 1.5 mM was achieved. The proposed biodegradable OECTs platform holds the potential to accelerate advancements in organic electronic devices, particularly in the fields of sustainable and transient electronics.

a Fabrication process of degradable OECTs: 1) PLA substrate casting and silanization, 2) carbon paste printing and curing, and 3) PEDOT:PSS channel inkjet printing and curing. b Qualitative assessment of device degradation testing at different time points (Pristine, 3 weeks, and 4 weeks). Reproduced with permission79. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature.

Benefiting from the intrinsic biocompatibility, degradability, formability, and flexibility, biopolymers hold great promise as flexible substrates, dielectric layers, and semiconductor films for high-performance wearable and implantable biosensors81. Beyond their direct use as flexible sensor materials, the applicability and functionality of these biomaterials can be further augmented through various treatment processes, such as carbonization, thereby expanding their potential in bioelectronic applications82.

Here, the key components and performances of OECT-based glucose sensors are summarized in Table 1. Currently, the preparation of OECT-based high-performance glucose sensors can be approached from four distinct perspectives: 1) Suitable sensing materials (e.g., PtNPs, Nafion, ferrocene, chitosan) with GOx or enzyme-free methods for gate modification. 2) New OMIECs design (particularly n-type semiconductors), or channel functionalization (e.g., AuNPs, Nafion, [EMIM][PF6]/DBSA doping), for higher amplification capability (high gm). 3) Flexible/stretchable materials (e.g., biopolymers and fibers) for the development of OECTs as wearable and implantable devices. 4) Biodegradable/biocompatible/bioresorbable materials for the fabrication of OECT-based glucose sensors.

Dopamine detection

DA is a neurotransmitter that acts as a key player in kidneys, central nervous, endocrine, and cardiovascular systems83. A detailed understanding of the precise physiological concentrations of DA in the human body is critical for mitigating or preventing cognitive impairment, hyperarousal, and other severe neurological disorders84. This subsection focuses on recent advances in OECT-based DA biosensors.

The sensing mechanism of OECT-based DA sensors resembles that of glucose sensors, where DA is electro-oxidized to o-dopamine quinone on the surface of the functional gate electrode, generating a Faradaic current, leading to changes in the potential at the electrolyte/gate interface. Consequently, DA can be detected based on the change of VeffG and ID83,85. OECT-based DA sensors were first proposed by Tang et al. in 201183, where different gate electrodes, including graphite, Au, and Pt electrodes were utilized, respectively. Pt gate electrode was demonstrated to achieve high sensitivity at VG of 0.6 V. Besides, the detection limit for DA was less than 5 nM, which was one order of magnitude lower than that of a conventional simultaneous electrochemical measurement. However, this work did not consider selectivity. Hence, Liao and co-workers prepared an OECT-based DA sensor with Nafion/chitosan and graphene/reduced graphene oxide (rGO) flakes modified Pt gate (Fig. 8a-c)86. It is claimed that chitosan and Nafion films can somehow enhance the selectivity of sensors, owing to the distinct electrostatic interactions that exist between the polymer films and the analytes. Graphene flakes are used to improve the response and lower the detection limit of the device due to their exceptional charge transport properties and high surface-to-volume ratio. Such a device further improved sensitivity and lowered the detection limit to 5 nM, which is suitable for low-cost and disposable sensing applications. Similarly, Ji et al. demonstrated a highly sensitive and selective flexible OECT, comprising a gate made of Nafion and rGO-wrapped carbonized silk fabric (CSF) (Fig. 8d)6. The hierarchical structure of the CSF improved electrode conductivity and prevented rGO and Nafion aggregation. Therefore, it exhibited advantageous characteristics, including a low detection limit (1 nM), high sensitivity, and high selectivity for the detection of DA. Subsequently, the same group also constructed a flexible OECT-based DA sensor using nitrogen-oxygen co-doped carbon cloth (NOCC-O, obtained under the oxidative atmosphere) as the gate87. An improved voltage sensitivity of up to 151 mV/decade and good selectivity were obtained. The higher selectivity of NOCC-O for DA is attributed to the enriched O-I and N-6 atoms, which are more favorable for the adsorption and oxidation of DA on its surface. This confirms the effectiveness of heteroatoms on carbonaceous electrodes in developing high-performance OECT sensors. Moreover, as OECTs are inherently amplifiers, Liang et al. developed OECTs embedded in flexible polyimide substrates prepared as DA sensors. A split aptamer is tethered to the Au gate electrode88, and DA binding can be detected by the OECT-based sensor, showing a detection limit of 5 fM. Tang et al. also prepared an OECT-based DA sensor with an overoxidized MIP/Pt (o-MIP/Pt) gate (Fig. 8e)89. To enhance selectivity for DA detection, a polypyrrole (PPy) film is deposited on the Pt gate electrode as an anion barrier, resulting in significantly improved DA selectivity and a detection limit of 0.35 μM. (Fig. 8f). Harnessing the advantages of low cost and ease of electrochemical deposition, MIPs provide a promising avenue for the fabrication of highly selective OECT-based DA sensors.

a Pt gate modified with Nafion (or chitosan) and graphene (or rGO) flakes of an OECT-based DA sensor and b response of ID to the addition of DA and c change of VeffG as a function of analyte concentration. a–c Reproduced with permission86. Copyright 2013, Royal Society of Chemistry. d Schematic diagram and ID vs. times of the Nafion/rGO/CSF-based OECT sensor. Reproduced with permission6. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. e Overall structure diagram and f NCR of the OECT sensors with Pt gate and o-MIP/Pt gate under different accumulative analyte concentrations. Note that the MIP is templated by DA. Each error bar is derived from the NCR of five devices. Reproduced with permission89. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society.

In addition to gate modification, channel functionalization of OECTs is another way to enhance the performance of DA sensors. For example, Chou et al. prepared OECTs by immobilizing AuNPs on thiol-functionalized PEDOT films90, which significantly enhanced gm and sensitivity of OECT-based DA sensors. It exhibited a good current response in the DA range from 50 nM to 100 μM, with a detection limit of 37 nM. Tseng et al. incorporated DMSO, GOPS, and anionic fluorinated surfactants into PEDOT:PSS channel to modulate electrical conductivity, self-healing ability, and tensile properties91. Then stretchable OECT-based DA sensors on PDMS substrates were fabricated. Such sensors showed a detection limit of 61 nM, paving the way for the development of flexible DA sensors. Furthermore, a supramolecular method based on the integration of PEDOT:PSS with cationic molecular blocks for OECTs fabrication was proposed by Diforti et al.92. The PEDOT:PSS film was prepared by using a layer-by-layer self-assembly technique, achieving nano-precision integration with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) (Fig. 9a), where excellent sensitivity (279 mV/decade) and a wide working range (1–300 µM) were demonstrated (Fig. 9b). These advancements highlight the significant potential of channel functionalization strategies in enhancing the sensitivity, flexibility, and performance of OECT-based DA sensors, offering new avenues for next-generation bioelectronics.

a Schematic representation of the layer-by-layer nano-construction of the PEDOT:PSS/CTAB-based OECTs, and b transfer curves under different concentrations of DA. Reproduced with permission92. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. c Schematic diagram of FSP-OECTs for the detection of DA in vivo. d Calibration plot of ID of different DA concentrations and e selectivity test of FSP-OECT to 50 μM DA against biologically relevant electroactive species including 50 μM 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), 50 μM UA, and 200 μM AA, respectively. c–e Reproduced with permission7. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. f Device schematics and the fabrication steps of PEDOT:PSS spearhead gate and channel of the needle-type carbon nanoelectrodes (CNEs) OECTs, and g ID versus time curve during the incremental addition of DA. Reproduced with permission97. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature.

In addition, the response to analytes by directly monitoring the steady-state ID of OECTs is susceptible to noise, it is challenging to obtain stable signals with high signal-to-noise ratios. Therefore, researchers have also combined OECTs with other testing methods to achieve a more stable and accurate detection of DA. For example, since oxidation of different analytes occurs at different potentials, scan rates are an important parameter to achieve a good resolution. Gualandi et al. developed an all-PEDOT:PSS-based OECT by utilizing a potentiodynamic approach to achieve selective DA detection93. This DA sensor exhibited a linear calibration plot of DA in the concentration range of 0.005–0.1 mM, achieving a detection limit of 6 μM. Fast Scanning Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV), leveraging the diverse oxidation potentials and reaction kinetics of neurochemical species, offers high selectivity and spatiotemporal resolution in detecting neurotransmitters, distinguishing them in the voltammogram94. On this basis, a fast-scanning potential (FSP) gated OECT was prepared (Fig. 9c–e), which used the ID or gm as the output parameter and investigated the relation between the ID or gm and DA concentration7. Such configuration combined the selectivity of FSCV with the high sensitivity of OECTs, enabling highly sensitive and selective sensing of DA in the brain, achieving a sensitivity of 0.122 A/M and a detection limit as low as 5 nM. Similarly, Tybrandt et al. designed OECTs to amplify the FSCV signal, which enabled the successful measurement of DA concentration within 10 μM95. To account for the signal-to-noise ratio in the detection process, Wang and co-workers pioneered a novel electrochemical sensing method to simultaneously measure gm and phase of alternating current (AC) channel for OECT-based DA sensors5. Given that different concentrations of DA resulted in alterations to the gm of the sensor, rapid DA identification was feasible. The detection limit of this sensor was as low as 1 nM, and the AC method provided an experimental basis for OECTs in noisy environments and complex biological systems. These studies demonstrate that integrating OECTs with advanced electrochemical techniques significantly enhances dopamine detection sensitivity, selectivity, and stability, enabling promising applications in complex biological environments.

Furthermore, new structures and manufacturing methods for OECT-based DA sensors are constantly being developed. For example, Qing and co-workers presented a fully filament-integrated fiber OECT based on polyvinyl alcohol-co-PE nanofibers (NFs) and PPy nanofiber network96. Using NFs/PPy filaments as gates, the system outperformed that based on Au and Pt filaments. It demonstrated immunity to interferences, good selectivity, high sensitivity, and excellent reproducibility in the DA detection range from 1 nM to 1 μM. Especially, Mariani et al. developed a needle-type OECT sensor by using single- and double-barrel carbon nanoelectrodes for the fabrication of nanometer-sized OECTs (Fig. 9f)97. The needle OECTs can be precisely positioned utilizing a macro handle, and the sensing performance is validated through DA detection, with an accurate detection at low concentrations down to 1 pM (Fig. 9g). The spearhead structure may be appropriate for stereotactic insertion into deeper brain regions for medical diagnostics. On the other hand, 3D stereolithography was also applied for the rapid fabrication of OECTs by Bertana et al.98. They explored a resin composite based on PEDOT:PSS and light-cured poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate for the preparation of OECTs. Such a device can also act as a DA sensor, which showed a significantly enhanced sensitivity of 0.41 V/decade. By integrating OECTs as arrays, Xie et al. enabled the detection of DA release in rat brains under different physiological conditions, with a detection limit of DA release as low as 1 nM99. This technique demonstrated the capability of OECT arrays for electrochemical analyses of the nervous system and in vivo detection.

Detailed compositions and key performance parameters for OECT-based DA sensors are summarized in Table 2. It can be concluded that the preparation of DA sensors based on OECTs focuses on the following aspects: 1) Utilization of appropriate gate materials (Pt, Au or carbon) and gate functionalization (e.g., Nafion, graphene, rGO, and PPy film) for higher sensitivity. 2) Optimization of semiconductor materials, e.g., doping AuNPs, DMSO, GOPS, and CTAB in PEDOT:PSS to improve performance for direct DA sensing. 3) Combination with electrochemical methods (e.g., FSCV) and development of novel OECT structures (e.g., needle-type or arrays) for performance enhancement and application scenario expansion. 4) Improve the selectivity of DA. Note that the development of OECT-based DA sensors still requires further development in terms of selectivity, since DA coexists in organisms with various neurotransmitters and metabolites that share structural and property similarities, making it challenging to achieve highly specific recognition of DA. Therefore, if an antibody, aptamer, or enzyme that can specifically recognize dopamine can be developed, it is believed that it will be able to effectively solve this problem.

Lactate detection

LA was previously identified as a metabolic waste product in hypoxia. However, Rabinowitz et al. have unveiled its pivotal function as a crucial energy transporter, suggesting a potentially paramount role in organism holistic energy metabolism100. Therefore, the detection of LA levels offers new avenues for investigating the pathogenesis of diabetes and other disorders associated with energy metabolism. This necessitates reassessing the clinical significance of LA levels testing in these contexts101,102. This section will examine recent developments in OECT-based LA sensors.

The mechanism of LA sensing is that, with the incorporation of lactate oxidase (LOx), LA is oxidized to pyruvate along with the reduction of LOx, generating a Faradaic current in the gate. This changes the potential at the gate/electrolyte and electrolyte/channel interfaces, converting the biochemical signal into an electronic signal that can be detected by testing the response of VeffG or ID to different LA concentrations. Therefore, improving electron conversion efficiency on the gate is one of the key research focuses of LA sensors. Here, the classical LOx reaction system serves as the cornerstone for gate modification strategies, facilitating advancements in the development of OECT-based LA sensors. For example, OECT-based LA sensors were prepared by Gualandi et al. with the utilization of LOx-functionalized gates and immobilization in Ni/Al layered double hydroxide (LDH) by a one-step electrodeposition procedure (Fig. 10a–c)103. The structure allowed the minimized amount of enzyme required during electrodeposition and showed a good linear response range of 0.05–8 mM and a detection limit of 0.04 mM. Similarly, OECT-based sensors for LA detection in sweat were reported by using LOx- and chitosan-modified Pt gate electrodes, which showed high sensitivity. However, the sensing range is limited to values below ~1 mM104. To obtain sensors with high sensitivity and low detection limit, Ji and co-workers made OECTs by modifying the gate electrode with LOx and PtNPs55, along with the combination with a PDMS microfluidic channel. At last, realized a detection limit of LA detection as low as 1 μM. Moreover, the synthesis and refinement of novel OMIECs also represent an effective strategy for enhancing the performance and functionality of OECT-based LA sensors. For example, with the continuous development of n-type semiconductor materials, an all-polymer micron-sized n-type OECT was further designed for LA detection using P-90 as semiconductor material (Fig. 10d–f)10. The selected n-type materials can effectively accept electrons from enzymatic reactions, resulting in fast redox reactions, and are well suited for biosensing. Such a device exhibits a wide dynamic detection range from 10 μM to 10 mM and a sensitivity of 0.802 NCR/decade. Improving electron conversion efficiency at the gate is crucial for advancing OECT-based LA sensors, with ongoing developments in gate modifications and materials enhancing sensitivity and detection limits.

a Structure of the LA sensor with LOx immobilized with LDH matrix. b ID vs. time curves and c calibration curves obtained for the OECT-based LA sensor. a–c Reproduced with permission103. Copyright 2020, MDPI. d Schematic and e proposed mechanism of LA sensing based on n-type OECT and f NR of the device with different LA concentrations. d–f Reproduced with permission10. Copyright 2018, American Association for the Advancement of Science. g Illustration of PVF composite conductive nanofibers-based OECTs and h ID vs. time curve for LA detection in human sweat. Reproduced with permission107. Copyright 2023, Elsevier.

Recent advancements in fiber-based OECTs have facilitated the development of flexible and wearable biosensors, offering unprecedented opportunities for applications in continuous health monitoring and personalized medicine. Therefore, some fiber OECTs were also fabricated for the simultaneous detection of LA102,105,106,107, Among them, Tao and colleagues reported fiber-based dual-mode OECTs for LA sensing102. The sensor exhibited sensitivities of 69.97 mV/decade in depletion mode and 47.8 mV/decade in accumulation mode, respectively, demonstrating a robust linear response spanning a wide dynamic range from 100 pM to 10 mM. Similarly, Zhang et al. prepared multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) and PPy composites for the first time on a fiber surface106, which acted as the channel and was gated by a solid electrolyte composed of movable ions, leading to the integration of a fiber OECT-based LA sensor. The sensor provided high sensitivity, excellent selectivity, a fast response time of 0.6–0.8 s, and a wide linear response range of 1 nM–1 mM for LA detection. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 10g, h, Shen et al. crafted multilayer composite electrodes by amalgamating MXene and PEDOT:PSS onto polyvinyl formal (PVF) nanofiber bundles107. These electrodes were then integrated with LOx and Nafion into fiber OECTs as gate electrodes, yielding exceptional sensitivity and selectivity for real-time monitoring of LA concentrations in human sweat. This device demonstrated a good linear response in the range of 1 nM–100 mM, a 0.442 NCR/decade sensitivity, and a fast response time within 0.5 s. These advancements in fiber-based OECTs for LA detection underscore their potential for real-time, flexible, and wearable biosensing, offering exciting prospects for continuous health monitoring and personalized medicine.

In addition, there are several other methodologies for the preparation of LA sensors. For example, Scheiblin et al. fabricated screen-printed OECTs47, where a sol-gel/chitosan/ferrocene/LOx composite was drop-cast onto the transistor surface to serve as the electrolyte. This OECT exhibited a narrow detection range for LA (0.1 mM–2.3 mM), which was rigorously validated and successfully tested in authentic human sweat samples, showcasing its potential for non-invasive biomonitoring applications. Braendlein et al. integrated two OECTs made from two different functionalized PEDOT:PSS into a Wheatstone bridge layout to investigate the effect of LA levels on diseases such as cancer108. One of the main advantages of the circuit was its inherent background subtraction, which significantly improved accuracy and enabled the successful detection of LA in tumor cell cultures. This LA sensor exhibited a linear response within a concentration range of 30–300 μM, achieving a detection limit as low as 10 μM. The initial utilization of miniaturized sensor circuits in clinically pertinent assessments was of paramount importance for the monitoring of cancerous tumor progression and the assessment of treatment efficacy.

A list of research publications on OECT-based LA sensors with their key parameters is summarized in Table 3. Performance of OECT-based LA sensors can be enhanced by four different strategies: 1) Gate modification (e.g., combination of LOx-modified gates with chitosan, PtNPs, Nafion, PVF, MWCNT, PPy). 2) Optimization of OMIECs or channel functionalization (e.g., incorporating MXene and PEDOT:PSS), especially the continuous development of n-type materials, which is conducive to improving the performance of LA sensors. 3) Advanced the design of fiber OECT-based LA sensors, which has great potential to advance the field of flexible and wearable biosensors with great potential for seamless integration into a wide range of applications. 4) Integration with microfluidics and electronic circuits, which can facilitate the development of miniaturized and highly functional sensing systems.

Other small molecule detection

OECTs can also be used to detect other small molecules, such as AA87,109,110, UA111,112,113, cortisol114,115,116, etc.

AA is a water-soluble cellulose that contributes to collagen and neurotransmitter biosynthesis117, free radical scavenging118, and iron uptake in human intestinal cells119. To develop a high-performance AA sensor, Xi et al. fabricated OECTs equipped with NOCC gate electrodes87. They revealed that surface engineering of the NOCC electrodes, specifically through modulation of the carbonation atmosphere, could effectively enhance both sensitivity and selectivity. Subsequently, the sensor successfully detected AA with a remarkable sensitivity of 240 mV/decade in the concentration range of 5 μM to 1 mM. To advance the treatment of neurological diseases, precise detection of chemicals within human brains is crucial. Feng and colleagues designed an innovative all-polymer fiber OECT (PF-OECT) tailored for intracranial implantation in mice (Fig. 11a-c)109. The PF-OECT demonstrated stable and highly sensitive monitoring of AA concentrations ranging from 10 to 1200 μM. Furthermore, the device exhibited exceptional biocompatibility with brain tissue, resilience against biofouling, and proficiency in analyzing complex analytes, underscoring its potential as a powerful tool for neurochemical research and therapeutic applications. Additionally, to enable more straightforward and routine detection of AA in foods, Contat-Rodrigo et al. designed an all-PEDOT: PSS OECT for the rapid, efficient, and cost-effective determination of AA, showing a detection limit of 80.1 μM, allowing sensitive quantitative monitoring of AA in foods110. These works on OECT-based AA sensors, with improvements in sensitivity, selectivity, and biocompatibility, demonstrate their potential in diverse fields such as neurological research and routine food monitoring.

a Schematic illustration and b circuit diagram of PF-OECTs. c ID response toward the sequential addition of AA in the electrolyte. a–c Reproduced with permission109. Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH. d Structural diagram of textile chemical sensors based on OECTs and ID versus times response with the addition of different concentrations of UA. Reproduced with permission121. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. e Schematic of OECT-based wearable cortisol sensors. Reproduced with permission115. Copyright 2018, American Association for the Advancement of Science. f Schematic and normalized ID versus time of OECTs cortisol sensor based on poly (EDOT-COOH-co-EDOT-EG3) nanotubes as the channel layer. Reproduced with permission116. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society.

UA is a biomarker of bacterial infection in wounds, which is associated with a variety of clinical conditions120. For UA sensing, Yang and colleagues reported that OECT-based UA sensors on nylon fibers demonstrated satisfactory performance76. The gate electrodes constructed from multilayer Nafion/graphene/PANI/uricase-graphene oxide (UOx-GO), exhibited a detection limit of approximately 30 nM for UA detection. In addition, several alternative approaches can be employed in the preparation of UA sensors. For example, Arcangeli et al. proposed an innovative OECT-based textile sensor for real-time selective monitoring of UA in wound exudate (Fig. 11d)121. The results demonstrated that the sensor was capable of reliable UA detection within the range of 220–750 μM, which is beneficial for monitoring wound healing for further wound diagnosis and patient rehabilitation. Tao et al. fabricated fiber OECTs with MIP/PEDOT/carbon fiber gates112, demonstrating a linear response for UA concentrations from 1 nM to 500 μM and an SI of 100 μA/decade. Subsequently, the utility of the sensor was successfully evaluated by detecting UA in urine samples. In addition to UA, quantitative detection of urea is crucial not only in medical diagnostics but also in food safety and environment monitoring. Thus, Berto et al. showed urea biosensors based on urease entrapped in a crosslinked gelatin hydrogel, deposited onto all-PEDOT:PSS-based OECTs122. Ions produced by urea hydrolysis are successfully detected by modulating conductivity, with a detection limit as low as 1 μM and a fast response of 2–3 min. These devices position enzymatic OECT-based biosensors as appealing candidates for monitoring UA/urea levels at the point of care or in the field.

Cortisol is a glucocorticoid hormone used to regulate blood pressure, raise glucose levels, and promote carbohydrate metabolism123. Measuring cortisol levels can help prevent severe stress, fatigue, and the onset of mental illnesses. Parlak et al. designed a biomimetic polymer membrane serving as a molecular memory layer for stable and selective cortisol recognition115. As depicted in Fig. 11e, the OECT-based wearable cortisol sensor was seamlessly integrated with an array of microcapillary channels. This advanced design enabled precise collection, efficient transmission, and continuous monitoring of sweat, thereby facilitating accurate cortisol detection with an SI of 2.68 μA/decade. Besides, a novel nanostructured embedded OECT-based sensor for real-time detection of cortisol was also reported116. Such a device used a bilayer channel confined by a PEDOT:PSS underlayer and a nanostructure-decorated upper layer engineered from the monomers EDOT-COOH and EDOT-EG3 through template-free electrochemical polymerization (Fig. 11f). This sensor demonstrated real-time cortisol detection over a linear range from 1 fg/ml to 1 μg/ml, achieving an exceptional detection limit of 0.0088 fg/ml. Similarly, Demuru et al. overcame the challenge of accurately and cost-effectively detecting cortisol in biofluids by developing label-free wearable OECT sensors coated with cortisol-specific antibodies114. This sensor showed an SI of up to 50 μA/decade, allowing direct sweat collection for monitoring cortisol levels in human sweat over a short period for health assessment. These studies on OECT-based cortisol sensors reveal exceptional sensitivity and real-time monitoring, offering effective solutions for non-invasive health assessment.

Key parameters of the reported studies on the detection of indicated small biomolecules are then summarized in Table 4. The remarkable progress in the ability of OECT-based biosensors to detect small biomolecules heralds a promising epoch in biosensor technology. This section underscores the pivotal advancements achieved in investigating small molecules, notably UA, AA, and cortisol, offering valuable perspectives for future research endeavors and refining the detection of subsequent small biomolecules. Subsequent work on the detection of other small molecules can be initiated in three ways: 1) By continuously optimizing the materials and designing new sensor structures to improve the sensitivity and detection limit. 2) The applicability of OECT-based biosensors can be expanded with the incorporation of suitable specific recognition methods, thereby enabling the detection of additional small molecules. 3) Preparation of OECT-based systems for realizing non-invasive sensing, in-situ detection, and portable detection.

OECTs for macromolecule detection

Biological macromolecules are fundamental substances that constitute life, distinguished by their diverse biological activities and their critical roles in biological metabolism. This section provides a concise overview of OECTs for the detection of biomacromolecules, such as DNA11,12,42, RNA124,125, and proteins126,127,128.

DNA and RNA detection

DNA and RNA constitute indispensable components within the human body, serving as the foundational cornerstones for the storage, transcription, expression, and regulation of genetic information, which is fundamental to the sustenance of all life processes. Quantitative DNA and RNA measurements play an indispensable role in biomedical and genomic applications, including cellular sensing129, virus detection130, cancer monitoring131, and infectious disease diagnosis132. DNA and RNA sensors have developed rapidly in recent years and can be realized by different preparation methods and operating mechanisms. This chapter highlights the progressive development of DNA/RNA sensors, transitioning from graphene transistor-based designs to those utilizing OECTs and organic photo-electrochemical transistors (OPECTs).

For DNA/RNA sensing, the DNA/RNA probe is usually fixed on the gate electrode. When target DNA/RNA binds to the DNA/RNA probe, the gate potential changes due to the charge redistribution in the local region of the gate electrode/solution interface, which would further affect the change of ID12,133. Solution-gated graphene transistors have recently attracted considerable interest for their potential applications in real-time and highly sensitive biosensing134. For example, Li et al. developed a DNA sensor by modifying single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) probes on Au gates along with graphene as the transistor channel135. Such a sensor showed an SI of 5 μA/decade in the linear range of 1 fM–5 μM and a detection limit of 1 fM. Similarly, Deng et al. also proposed a graphene transistor where carbon quantum dots (CQDs) were attached to the gate surface136. Subsequently, ssDNA probes were immobilized on the CQDs. This configuration enabled the detection of target DNA molecules at concentrations as low as 1 aM, facilitating rapid and highly sensitive detection of ultralow concentrations of DNA molecules (Fig. 12a, b). In another study of Deng, the ssDNA probes were anchored to the Au gates to make RNA sensors137. This setup enabled the probe to hybridize with the early prostate cancer-relevant biomarker, miRNA-21, leading to a detectable voltage shift in the transfer curve of the transistor. This sensor proved to be highly advantageous due to the low detection limit (10−20 M) and rapid response time, making it effective for the fast and sensitive detection of miRNA-21 molecules. Although significant progress has been made in DNA/RNA sensing using graphene transistors, their sensitivity still requires further enhancement to meet the demands of ultra-low concentration detection in complex biological environments.

a Schematic diagram of the DNA sensor structure and the recognition process of hybridization and b ΔID of the sensor as a function of the different concentrations of DNA. Reproduced with permission136. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. c Schematic diagram of the integration of OECTs and microfluidic systems, along with the DNA modification and hybridization on gate electrode surfaces. d VG shifts of OECTs induced by the conventional hybridization (blue) and pulse-enhanced hybridization (red) of DNA on gate electrodes at different concentrations of target DNA. c, d Reproduced with permission139. Copyright 2011, Wiley-VCH.

The development of biosensors has been significantly advanced by the inherent signal amplification capabilities of OECTs. These features have notably enhanced the detection limits, sensitivity, and response times of biosensors, establishing OECTs as a potent platform for the sensing of DNA and RNA138. For example, an OECT-based DNA sensor was integrated with a flexible microfluidic system, and ssDNA probes were immobilized on the Au gate electrodes to recognize analytes (Fig. 12c). These sensors demonstrated the ability to detect complementary DNA sequences at concentrations as low as 1 nM. Moreover, the detection limit could be further extended to 10 pM when the hybridization of DNA is enhanced by applying an electric pulse to the gate electrode in the microfluidic channel, showcasing its high sensitivity and adaptability for low-concentration DNA detection (Fig. 12d)139. Tao et al. introduced porous anodized aluminum oxide (AAO)-Au as the gate electrodes of OECTs for DNA sensing. The device combined with peptide nucleic acid probes could successfully detect complementary DNA sequences at concentrations as low as 0.1 nM and exhibited good linearity in the range of 0.5–12.5 nM11. As shown in Fig. 13a, b, Peng et al. fabricated a flexible OECT-based sensor on a flexible poly(ethylene terephthalate) substrate using carbon electrodes as source and drain and PEDOT:PSS as the semiconductor124. By modifying the Au gate with AuNPs to immobilize the capture DNA probes for microRNA (miRNA) detection, such a device enabled ID variations resulting from the hybridization between DNA and miRNA, achieving the detection of miRNA at concentrations as low as 2 pM. Similarly, Chen et al. introduced a hybridization chain reaction (HCR) and deposited AuNPs on the gates of OECTs for the first time to make DNA biosensors12. This increased VG offset, thereby enhancing the sensitivity to 42 mV/decade and achieving good linearity within the range of 0.1 pM to 1 nM. To achieve easier probe fixation, a study on fully screen-printed OECTs utilizing polydopamine (PDA) membranes to modify the carbon gates for the attachment of the analyte was conducted140. This approach enabled rapid functionalization with ssDNA, achieving detection limits as low as 0.1 pM for complementary DNA strands. For more convenient miRNA detection, Fu et al. constructed a portable and smartphone-controlled biosensing platform based on OECTs that enabled rapid and highly sensitive analysis of miRNA biomarkers13. This OECT-based miRNA sensor showed a wide linear range (10−6–10−14 M), enabling ultra-sensitive detection of minute miRNA levels in cancer cells. It has been effectively used to analyze miRNA expression in mouse tumor blood samples, differentiating even early-stage cancer miRNA levels. This work offers a cost-effective solution for mobile diagnostics across various diseases. These studies demonstrate that OECTs exhibit excellent performance and significant potential in DNA/RNA sensing, highlighting their advantages in sensitivity and real-time detection for practical applications.

a Schemes demonstrating the principle and b the calibration plots of miRNA21 biosensors based on OECTs. Reproduced with permission124. Copyright 2018, Springer Nature. c Structural diagram of OPECT and schematic of the charge transfer between CdS QDs and indium tin oxide (ITO) gate electrode, d ΔI/I as a function of the concentration of ssDNA targets. Reproduced with permission133. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH.

By employing OPECTs, significant advancements have been achieved in DNA/RNA sensors. For example, Song et.al combined OECTs with a photoelectrochemical gate modified with CdS quantum dots (CdS QDs) to form an OPECT for DNA sensing133. The sensing mechanism of the OPECT-based sensor is attributed to the target DNA being labeled with AuNPs and captured onto the gate (Fig. 13c), which subsequently affects charge transfer through exciton-plasmon interactions between CdS QDs and AuNPs. In Fig. 13d, as ΔI/I caused by the pure PBS solution (baseline noise) and 10−15 M of target ssDNA are 1% and 3.7%, respectively, the detection limit (signal response is three times higher than the baseline noise) of this OPECT-based DNA sensor for ssDNA detection can reach 1 × 10−15 M. However, from the interpolation of the low-response (10−15 – 10−9 M) and high-response (10−9 – 10−6 M) linear trends (as visible in Fig. 13d), more realistically the detection limit may lie between 0.1 and 1 nM. Moreover, it can be observed that the linearity in the 10−9 – 10−6 M range is poor, which may result in an inaccurate detection limit. It may be necessary to combine other methods, such as statistical formula-based approaches, to validate and optimize the calculation of the detection limit. This concern can also be extended to the calculation of detection limits in other studies. Furthermore, OPECTs can also be used for RNA detection, Gao et al. demonstrated biological modulation of surface capacitance in OPECT-based biosensors141, exemplified by a CdS/TiO2 nanotubes photoanode integrated with HCR amplification for biomarker miRNA-17 detection. Such a device achieved miRNA detection in the linear range of 1 pM to 1 μM, with a detection limit of 1 pM, which provided a versatile mechanism for more advanced OPECTs to be used in the field of biosensing. Ju et al. also pioneered a DNA intercalation-enabled OPECT for miRNA detection142. They achieved the intercalation of [Ru(bpy)2dppz]2+ (bpy = 2, 2′-bipyridine, dppz = dipyrido [3, 2-a: 2’, 3’-c] phenazine) within the duplex DNA produced by a miRNA-initiated HCR. Upon light stimulation, this intercalation generated anodic photocurrent, resulting in target-dependent variations in VG and consequently modulating ID. This work enabled quantitative analysis of miRNA-21 with a wide linear range and a low detection limit of 5.5 fM.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in developing nanometer-scale porous organic reticular materials, especially metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs)143. Their distinctive characteristics, including large surface areas, precisely regulated pore structures, enhanced functionalities, and unique catalytic activities, render them promising candidates for electrochemical biosensors144. In Fig. 14a–d, Wang and co-workers reported an OPECT gated by photosensitive COF-LZU1 on mixed-ligand MOF (COF-on-MOF) upon appropriate exposure illumination145. The device exhibited a significant enhancement in signaling capabilities and facilitated subsequent functionalization of its gating mechanism through the growth of target G-quadruplex wires superstructure triggered by the target. This targeted growth resulted in a highly sensitive detection capability for human T-cell lymphotropic virus type II (HTLV-II) DNA, achieving a detection limit as low as 0.003 fM.

a Gate functionalization process where COF-on-MOF and target DNA trigger GWS growth. b Schematic of the COF-on-MOF OPECT. c IDS-step responses of the system to various concentrations of HTLV-II DNA, representing the disparity in values between the currents before and after illumination, and d the corresponding calibration curve. Reproduced with permission145. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH.

Key components and parameters of DNA/RNA sensors, including the progressive development of graphene transistors to OECT and OPECT technologies, are summarized in Table 5. The subsequent diverse perspectives offer profound insights and guide research endeavors toward the development of advanced DNA/RNA sensors: 1) Utilization of appropriate gate materials (e.g., Au, carbon, ITO) and gate functionalization (e.g., ssDNA, QDs, PDA membrane, porous AAO membrane, and AuNPs) for higher performance. 2) Combination of microfluidics and a portable smartphone-controlled biosensing platform for accurate and rapid DNA/RNA detection. 3) Integration COF/MOF with OECTs/OPECTs holds promise for more accurate and sensitive DNA/RNA detection. 4) Advancement of portable OECT-based DNA/RNA sensors for use in clinical diagnostics and point-of-care services represents a significant and valuable goal.

Protein detection

Protein is one key cornerstone of life activities, undertaking critical functions such as structural support, catalytic reactions, signal transduction, and genetic information expression146. Measurement of protein content is essential for medical diagnosis, biotherapy, and prevention of related diseases. This section summarizes the research progress in OECT-based protein sensors in recent years.

The detection of proteins by OECT-based biosensors is typically based on antigen-antibody interactions, where either antibody or antigen is immobilized as a biorecognition molecule on the gate or channel of OECTs. Upon binding to the target protein with a specific antigen or antibody tag, this interaction changes the ion concentration and distribution near the gate or within the channel, leading to changes in the VeffG or ID of the OECT-based protein sensors126,147.

With the outbreak of new coronaviruses, rapid and accurate detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) is necessary, which has therefore driven the development of OECT-based protein sensors. Since gate functionalization is a frequently employed method for the detection of proteins. Liu and colleagues designed OECT-based biosensors for the rapid and portable detection of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 15a, b)126. The gates of OECTs are functionalized with SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins, enabling them to selectively capture antibodies through a targeted antibody-antigen interaction. These sensors can communicate with mobile phones remotely and rapidly detect SARS-CoV-2 within 5 min, showing a linear range of 10 fM to 100 nM, which can meet the requirement of fast and point-of-care detection of COVID-19 antibodies. Fan et al. also developed an aerosol-jet-printed OECT-based biosensor by fixing the SARS-CoV-2 antibody on the Au gate147. Further analysis revealed that the OECT functions as an effective diagnostic platform for SARS-CoV-2, exhibiting high selectivity for the SARS-CoV-2 protein across a broad concentration range from 1 fg/mL to 1 μg/mL. This sensor achieved a detection time of only 10 min and exhibits a commendable accuracy of 70%. Similarly, Colucci also prepared OECT-based protein sensors for SARS-CoV-2 detection127, achieving a lower detection limit of 10−17 M with an incubation time of 30 min. Additionally, it exhibited selectivity and stability when exposed to similar proteins, maintaining the detection limit after 20 days of storage.

a Design scheme of a portable sensing system for SARS-CoV-2 detection by modifying the gates of OECTs and b its responses to SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G (IgG) in PBS, serum, and saliva samples with 5-min incubation under voltage pulses. Reproduced with permission126. Copyright 2021, American Association for the Advancement of Science. c Design and fabrication of OECTs for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and d Normalized response of LCB1-functionalized OECTs to SARS-CoV-2. Reproduced with permission150. Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH.

Traditional biosensors require an incubation step that can take hours, during which the biorecognition sites capture analyte molecules, making the detection process cumbersome and time-consuming. To address this, Koklu employed alternating current electrothermal flow (ACET) technology integrated with an OECT-based protein sensor to accelerate the operation148. Modifying the gate electrode with a nanoantibody-SpyCatcher fusion protein and using the n-type p(C6NDI-T) as the channel enabled stable and rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2. This innovative approach significantly reduced the detection time, achieving a detection limit of 1 fM. In contrast to gate functionalization, Song fabricated a biosensor using the carboxyl-conjugated polymer poly(3-(3-carboxypropyl) thiophene-2,5-diyl) (PT-COOH) as a nanoscale biomolecule receptor layer on the OECTs channel149. The biosensor achieved a detection limit of 10 fg/mL for SARS-CoV-2, which contributes to the further development of OECTs and protein sensors with nanoscale functionality in the active layer of the polymer. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 15c, d, a simple and low-cost approach to the fabrication of OECT-based SARS-CoV-2 sensors was also demonstrated by Huang and co-workers150. These sensors rely on a conjugated protein mini-binder to immobilize the analyte on the surface of the PEDOT:PSS channel, they were capable of detecting the concentration of the protein or the virus in less than half an hour. The advancements in OECT-based protein sensors have enabled rapid, sensitive, and portable detection of SARS-CoV-2, offering critical solutions for the swift diagnosis of novel coronaviruses.