Germline structural variant as the cause of Lynch Syndrome in a family from Ecuador

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in both genders worldwide1. Most CRC cases occur sporadically, but inherited mutations are responsible for 13–30% of CRC cases2. In this regard, Lynch Syndrome (LS) is the most common form of hereditary CRC. LS is an autosomal dominant disease caused by germline defects in the DNA-mismatch repair (MMR) genes, including MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 and EPCAM. These mutations lead to microsatellite instability (MSI), a hallmark of LS-related tumors. Moreover, the tumors do not present with BRAF mutations or MLH1 hypermethylation. LS is associated with increased risk for early-onset CRC, endometrial, stomach and other cancers3. Prevalence has been estimated to be around 1/300 individuals4.

It is of extreme importance for affected LS patients and relatives to identify the germline causative alteration to provide intensified surveillance to allow early diagnosis and prevention of cancer for those carrying the inherited defect. Current approaches for LS diagnosis typically involve the combination of clinical criteria, tumor testing, and genetic testing5. Diagnostic germline testing in suspected LS families generally include screening of the MMR genes by targeted gene-panel sequencing (for small coding or splicing-affecting genetic variants) and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) (for rearrangements). The International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumours (InSiGHT) locus-specific database collects more than 3000 unique germline sequence variants of the four LS-associated genes, being the more commonly mutated MLH1 and MSH26. It has been reported that about 50% of patients with suspected LS remain without a clear germline cause and they are designated as Lynch-like syndrome (LLS) cases7. More than half of LLS tumors present two somatic mutations in the MMR genes8. However, a significant proportion of LLS patients remain genetically unresolved despite both germline and somatic testing.

In this study, we report the identification and characterization of a novel germline structural variant involving the 3’-ends of the MLH1 and LRRFIP2 genes as the cause of LS in a family from Ecuador. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and transcriptomics allowed the identification of the genomic rearrangement and highlighted the importance of the use of these additional approaches to achieve a comprehensive molecular diagnosis in some LS patients.

Results

Case report

In this study, we present a family of Ecuadorian origin with a history of CRC and gastric cancer fulfilling Amsterdam II criteria (Fig. 1A). This family remained unconfirmed by germline testing for more than 10 years despite being clinically diagnosed with LS. In this LLS family, a sister of the index case (III:4) was attended at the high-risk clinic for gastrointestinal cancer of our hospital in 2012 for advice concerning her familial cancer history. Other family members presented cancer at young age, either CRC (40 y.o.) or gastric cancer (27 and 48 y.o.). When reported, endometrial cancer was not present in any of the family members. The index case of this family was affected with CRC at age 47. His tumor showed loss of both MLH1 and PMS2 proteins and was BRAF wild type. Tumor sequencing to detect MMR double somatic events was not pursued.

A Pedigree of the Ecuadorian family, where the index case is marked with an arrow. Black symbols represent individuals affected by either colorectal (upper right) or stomach cancer (lower left). Age of onset is also indicated. Female and male gender are circles and squares, respectively. Slashed individuals represent death. + symbol indicates carrier status for the rearrangement. – symbol indicates non-carrier status for the rearrangement. B MLPA results showing potential alterations in MLH1 exon 19 (probemix P003), and MLH1 exon 19 and exon LRRFIP2 exon 26 (probemix P248). C CGH array of index case indicative of a genomic alteration in the 3’ends of MLH1 and LRRFIP2 (red circle).

Genetic testing results

Germline testing for the MMR genes was performed using targeted gene-panel sequencing and revealed no potentially pathogenic genetic variants. Rearrangement analysis for the MMR genes using MLPA and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) detected an alteration affecting the 3’-ends of the MLH1 and LRRFIP2 genes (Fig. 1B, C). Subsequently, long-range PCR amplification was attempted on germline DNA, targeting the suspected area (primers designed before MLH1 exon 18 and before LRRFIP2 exon 26), but it was unsuccessful.

Genomic analysis/Whole-genome sequencing

To better characterize this putative rearrangement, we performed WGS. The structural variant (SV) callers Manta and Delly detected a complex rearrangement with three overlapping SVs, including a small inversion in MLH1 (0.91 kb, GRCh37 NC_000003.11:g.37088346_37089273inv), a large inversion involving MLH1 and LRRFIP2 (22.8 kb, GRCh37 NC_000003.11:g.37088713_37111528inv), and a tandem duplication in LRRFIP2 (37.88 kb, GRCh37 NC_000003.11:g.37099223_37137103dup), none of them previously reported in dbVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbvar/). The genomic rearrangement encompassed a total of 48.757 kb (GRCh37 NC_000003.11:g.37088346_37137103).

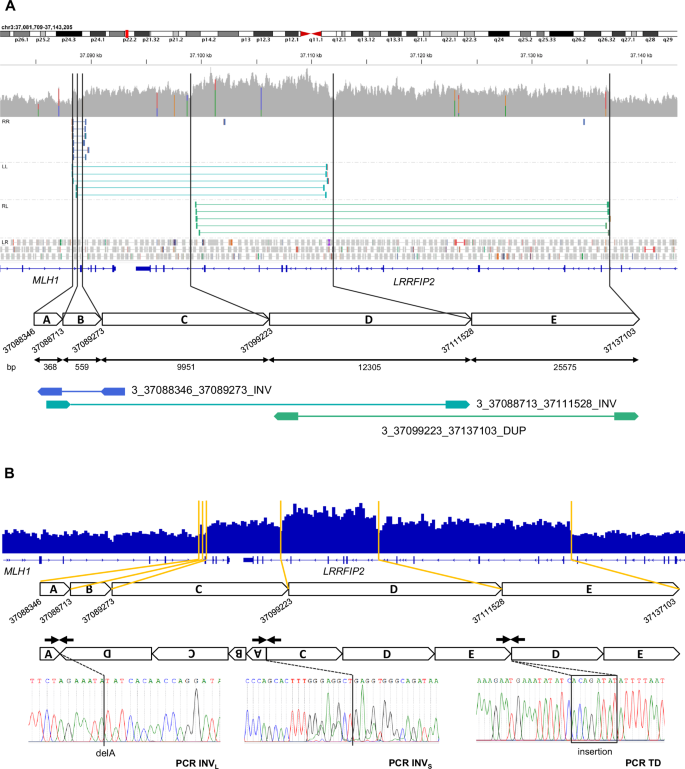

By examining the WGS data with the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV), we observed discordant read pair orientation and mapping distance, confirming the three SVs (Fig. 2A). We also noted an altered depth of coverage, that included not only the tandem duplication but the full complex rearrangement, indicating the presence of additional duplicated regions beyond the predictions of the SV callers. By using a simplified IGV coverage plot view, we were able to propose a fine-tuned map of the actual rearrangement, fitting the altered WGS coverage and the SV calling (Fig. 2B). The breakpoints of the three SVs were validated by Sanger sequencing at a nucleotide resolution, revealing small insertions and deletions at the novel junctions. The full characterization of this complex rearrangement confirmed that the variant calling was not able to detect some duplicated areas (A and C) as well as the additional duplication of region D, which corresponds to the overlap between the large inversion and the tandem duplication.

A Visualization of WGS data with Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV). Germline short reads from WGS allowed the detection of three SVs involving the 3’-ends of MLH1 and LRRFIP2. Representative paired reads with discordant pair orientation (RR, LL and RL) and aberrant mapping distance are depicted. A schematic map of the area of the rearrangement shows the three SVs and the six breakpoints, resulting in a five-segment map (A to E). The size of each segment in bp is indicated. The overlapped SVs are defined as a small inversion in MLH1 of 0.91 kb (fragments A and B, deep blue), a big inversion of 22.8 kb involving MLH1 and LRRFIP2 (fragments C and D, turquoise blue) and a tandem duplication of 37.88 kb in the LRRFIP2 gene (fragments D and E, green). B Characterization of the breakpoints of the SVs and proposed map of the rearrangement. IGV simplified coverage plot (IGV Count tool with an average read density window of 300 bp) allowed the characterization of the breakpoints and duplicated areas. The proposed map of the actual rearrangement fits the WGS coverage and the SV calling. Sanger sequencing profiles of the three PCRs (arrows) validated the breakpoints.

Transcriptomics

To further characterize the SV, we performed RNA-seq on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from the index case. Neither relevant gross alterations nor aberrant splicing patterns were detected in the RNA-seq data for MLH1 or LRRFIP2 (Fig. S1A). Relative expression levels of both genes were also measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR). No differences in MLH1 and LRRFIP2 expression were detected when using qPCR probes outside the rearrangement, whereas downregulation of MLH1 and upregulation of LRRFIP2 were evident when using qPCR probes located in the areas affected by the rearrangement (Fig. S1B). MLH1 downregulation would support the role of this complex rearrangement in causing LS. At the same time, LRRFIP2 expression levels could be compatible with the presence of some of the altered transcripts produced by the complex rearrangement not degraded by non-mediated decay. Although not detected by our analysis, it is also likely that this structural variant could lead to a truncated MLH1 protein or a fusion protein incorporating part of LRRFIP2, disrupting the final protein product. A similar effect has been observed in cases where EPCAM deletions impact the upstream MSH2 gene9. Additionally, taking into consideration the large area affected by this rearrangement (48.757 kb), it could be hypothesized that the topological architecture and predicted transcriptional associated domains in this region will also be affected, according to the data available at http://3dgenome.fsm.northwestern.edu/10 (Fig. S2).

PCR tests to detect the genomic rearrangement

PCR tests designed for breakpoint validation can be used to facilitate the screening of the large rearrangement in additional members of the family and other Ecuadorian CRC patients. Only carriers of the complex rearrangement will display a positive amplification when using primers of PCR TD, PCR INVL, PCR INVS and control PCR. The non-carriers will only amplify with primers of the control PCR (Fig. S3). By using these discriminatory primers, the same rearrangement was detected in the asymptomatic sister of the index case (III:4) who came to the clinic seeking advice regarding her family history of cancer. The SV was also confirmed by WGS. Recently, another asymptomatic sister of the index case (III:5) was found non-carrier of the rearrangement by PCR tests.

Discussion

In this study, we report the identification with WGS of a genomic alteration involving the 3’-ends of MLH1 and LRRFIP2 as the causative mutation in a LLS family from Ecuador. Molecular screening for this alteration has been offered to the rest of the family. The reference gastroenterologist and molecular laboratory specialists in the region of Ecuador where most of this family is located, have been contacted to facilitate the screening process. Additionally, this collaboration will enable the screening for this alteration in additional Ecuadorian CRC patients to determine if the genomic rearrangement represents a potential founder mutation, being more common than previously expected. It is worth noting that molecular studies for LS are scarce or nonexistent in some countries like Ecuador11. In this regard, our study enhances the molecular understanding of LS cases in this area with the subsequent benefit for both patients and the scientific community.

From our results, it can be highlighted that for some LS patients the current molecular diagnostic techniques (germline and somatic sequencing of the coding regions of MMR genes and MLPA) are not sufficient, and additional approaches should be used to increase diagnostic yield. Molecular rearrangements involving the MMR genes and their adjacent genes should be carefully examined, alongside the screening of non-coding MMR alterations. These features can be easily missed through standard targeted panel sequencing and MLPA12.

In order to detect structural variants, which can easily span repetitive or complex regions of the genome, long-read sequencing has become a powerful tool capable of reliably sequencing longer reads (10 kb), which enhances de novo assembly and mapping of the genome13. This powerful technique has been proven to capture most structural variants in the genome, compared to the capacity of short-read sequencing. For the case presented in this study, and due to the large area affected, its implementation might be challenging.

Exonic rearrangements in the MMR genes involving several exons are already an established mutational mechanism for LS14 and are currently screened as part of the routine tests involved in the molecular diagnosis of LS. The identified complex rearrangement was first suspected by MLPA and further characterized with WGS. Similar mutational events located in the 3’-end of MLH1 have been previously reported to be involved in LS15,16,17,18, suggesting that this genomic area could be a hotspot for these kinds of rearrangements. In the study by Zhu et al.15, they detected a duplication of MLH1 exon 19 in a patient fulfilling Amsterdam II criteria using MLPA. They described an extraordinarily high peak for this area corresponding to 12 calculated copies, which could imply a more complex rearrangement rather than just a simple duplication. In the study by Morak et al.16, they reported a paracentric inversion on chromosome 3p22.2 with one breakpoint in the genomic region of MLH1 and the other breakpoint downstream of MLH1, in the region of LRRFIP2, creating two new stable fusion transcripts between MLH1 and LRRFIP2. This alteration was detected in a CRC patient of a large family fulfilling the Amsterdam II criteria and segregating with CRC and/or endometrial cancer. In the study conducted by Pinheiro et al.17, they identified a deletion comprising exons 17–19 of the MLH1 gene and exons 26–29 of the LRRFIP2 gene, which turned out to be a founder mutation present in several LS patients of Portuguese ancestry. A recent study by Witt et al.18 detected a structural MLH1 variant in an Amsterdam criteria-positive family which corresponded to a copy-neutral inversion involving MLH1 and LRRFIP2.

In conclusion, we have been able to identify the complex mutational event spanning 48.757 kb affecting MLH1 (and the contiguous gene LRRFIP2) in a LLS family from Ecuador in which the tumor of the index case showed loss of MLH1 and PMS2 proteins, agreeing with the immunochemistry result that indicated a molecular defect in the gene. It is evident by our findings, and from previous studies, that the area of the 3’-ends of MLH1 and LRRFIP2 seem to be particularly prone to rearrange in some LS patients. Our case highlights the need to perform additional approaches, like long-read WGS and transcriptome analysis to the current established molecular diagnostic tests (targeted gene-panel, MLPA), for the subset of LLS patients without an identified germline or somatic alteration. These additional techniques can aid in the finding of these complex genomic structural variants that are present in some LS patients and remain undetected through current diagnostic techniques.

Methods

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained in all cases. The present study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínic in Barcelona (register number HCB/2021/0189, date of approval 01/06/2021), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975).

Germline testing: gene-panel, MLPA and CGH

Germline testing was conducted using commercial kits, including the TruSight Hereditary Cancer Panel (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) for targeted gene-panel sequencing, the SALSA MLPA probemixes P003 and P248 (MRC Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands) for multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, and the Human SurePrint G3 CGH Microarray 180 K (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) for comparative genomic hybridization. All procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions19,20.

Whole-genome sequencing

Short-read WGS was conducted on the germline DNA of the index patient. Briefly, a short-insert paired-end library was prepared using a PCR free protocol with the TruSeq DNA Sample Preparation Kit and the KAPA Library Preparation kit (Kapa Biosystems, USA). Sheared genomic DNA was end-repaired, adenylated, and ligated to specific indexed paired-end adaptors. The library was sequenced using a HiSeq 4000 (Illumina), in paired-end mode (2 × 150 bp) with a yield of >99 Gb and median coverage of 30x. Primary data analysis, image analysis, base calling and quality scoring of the run were performed using the manufacturer’s software, followed by generation of FASTQ files by CASAVA. Sequencing mapping to the reference genome, alignment and variant annotation was performed using GEM19, Picard tools (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/), GATK, SnpEff and SnpSift21,22,23,24. Manta and Delly were used with default parameters to call for structural variants on WGS data25,26.

Breakpoint PCR and Sanger sequencing

The regions flanking the approximate breakpoints of the CNVs identified with WGS were confirmed by PCR amplification using the following primers:

PCR TD (tandem duplication): forward GGTTAGTCCAAATTGAGAGTTGC; reverse TTCTCGGACAGAGGAGATTTTC.

PCR INVL (large inversion): forward TTACTCTCCATCCTCACCCG; reverse TGGTTCTTAGGGCTTGGGAG.

PCR INVS (small inversion): forward AATGCAGAAACAAAGGGAAAACT; reverse TTGGATTACAGGTACCCGCC.

Control amplification (DNA quality control): forward TTCTGAGCTCAAGCAATCCA; reverse CTCGGACAGAGGAGATTTTCA.

PCR using PCR TD, PCR INVL, and PCR INVS was only successful in carriers of the rearrangement. The control amplification served as DNA quality control and amplified in all samples.

RNA-seq

Blood from the index case was collected in PAXgene Blood RNA tubes, and RNA extracted using the PAXgene Blood RNA kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) as per manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA libraries were prepared using a TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit. Paired-end sequencing (2 × 100 base pairs) was performed on a HiSeq 2500 Sequencing System. Raw reads were subjected to quality control, adapters sequences and low-quality reads were removed, transcripts were aligned and quantified, and gene expression levels were normalized. Gene expression results were analyzed with DROP (Detection of RNA Outliers Pipeline)27.

Real-time PCR

RNA reverse transcription was performed with the High-Capacity cDNA reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was run on a QuantStudio1 System (Applied Biosystems) by using Taqman® Gene Expression probes against MLH1 (Hs00979919_m1; Hs00979922_m1) and LRRFIP2 (Hs00196889_m1; Hs00992892_m1), with GAPDH-FAM (Hs03929097_g1) as endogenous gene control for normalization purposes. Relative quantification was performed with the –∆∆Ct method.

Responses