Clinical and genetic characterization of patients with late onset Wilson’s disease

Introduction

Wilson’s disease (WD; OMIM #277900) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder of copper metabolism caused by variants in ATP7B, which encodes a copper-transporting P1B-type ATPase located in the trans-Golgi network1. ATP7B is mainly expressed in the liver, and functional defects in the protein lead to failure of ceruloplasmin biosynthesis and biliary copper excretion, with copper accumulating first in the liver and then in the brain, cornea, and other tissues2,3. As a result, patients with WD may present with hepatic and/or neurological symptoms, corneal Kayser–Fleischer (K–F) rings, and low ceruloplasmin levels1.

ATP7B is an 8-transmembrane (TM) domain protein comprising six metal-binding domains, an actuator (A) domain, a phosphorylation (P) domain, and a nucleotide-binding (N) domain. Copper transport is facilitated by conformational changes associated with ATP phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of D1027, involving the interaction of various domains of ATP7B4, and this process can be affected by variants in different domains to varying degrees. Hundreds of variants have been identified in patients with WD5,6, and their various effects on ATP7B stability, catalytic and transport activities, and intracellular localization have been reported7,8,9. Variants with partially affected ATP7B function may be accompanied by a slower accumulation of copper in the liver and other organs, and patients may develop symptoms at a later age or even never become symptomatic throughout their life, exhibiting low penetrance characteristics that affect the genetic and clinical prevalence of WD10,11.

Generally, patients with WD present with symptoms between the ages of 5 and 35 years, and only sporadic cases of late-onset WD have been described. In Europe, the prevalent variant H1069Q has been reported to be associated with late and neurological presentations of WD12, and a European study including 46 patients with an onset age over 40 years revealed no difference in diagnostic features or variant frequency compared to early-onset patients13. Chinese patients with WD exhibit completely different genetic characteristics, and our previous work indicated that the prevalent variants R778L and P992L, as well as protein-truncating variants (PTV), were predominant in patients with early-onset WD6. This work also provided us with a glimpse into the relationship between A874V and late-onset symptoms6; however, due to the limited number of cases, there is still a lack of comprehensive understanding of late-onset WD in China.

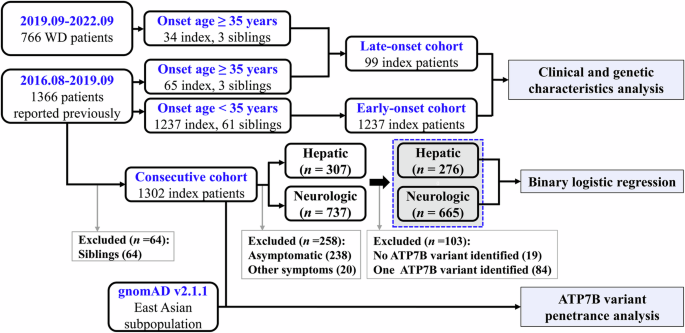

In the present study, we recruited a cohort of patients with an onset age greater than 35 years from our institution, and their genetic and clinical characteristics were collected and compared with those of patients with an earlier onset (less than 35 years)6. The penetrance of the variants of interest was assessed based on the East Asian allele frequencies of the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD, http://gnomad-sg.org/)14, and the phenotypic effects of the most common variants, represented by hepatic/neurologic presentation at onset, were evaluated based on our previous consecutive patients (collected between August, 2016 and September, 2019) who were examined with two potentially pathogenic ATP7B variants and onset with hepatic (n = 276) or neurological (n = 665) symptoms (Fig. 1)6.

Consecutive patients with WD between August 2016 and September 2019 (n = 1366), as well as patients with an onset age over 35 years between September 2019 and September 2022 (n = 37) were recruited. The late-onset cohort included index patients with an onset age over 35 years from these two periods, whereas the early-onset control only included index patients with an onset age below 35 years from August 2016 to September 2019. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed in the consecutive cohort of patients who were identified with two potential pathogenic ATP7B variants and onset with hepatic or neurological symptoms. ATP7B variant penetrance analysis was performed by comparing the allele frequencies of the variants in our consecutive cohort with the gnomAD allele frequencies of the East Asian subgroup.

Results

Demographic and clinical profiles

In total, 105 patients with an onset age over 35 years (average: 42.6 ± 7.3, range: 35.1–64.8), including 68 patients (65 index, 3 siblings) who had been reported in our previous study6, were recruited (Fig. 1). The patients were from 20 provinces in China (Supplementary Table 1), and their demographic and clinical data are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences were observed in sex, age at onset, age at diagnosis, or serum ceruloplasmin levels between the neurological and hepatic groups. However, we observed a greater proportion of patients with K–F rings (p = 0.025) and abnormal MRI findings (p < 0.0001) in the neurological group and a significantly greater proportion of patients with liver cirrhosis in the hepatic group (hepatic vs. neurological: 35/38 vs. 27/55, p < 0.0001). Among the 6 siblings, 3 were asymptomatic, 2 had an onset of hepatic symptoms similar to their probands but with a different onset age, and 1 had distinct symptoms and a different age at onset. Individual differences in copper accumulation in hepatocytes and intolerance to copper toxicity, as well as differences in allele dominance of ATP7B protein expression, might play a role in their clinical differences15. Moreover, compared to patients whose onset age was younger than 35 years (Supplementary Table 2), there was a lower proportion of males, a higher serum ceruloplasmin levels, and a greater proportion of patients with K–F rings in the late-onset cohort (Table 2).

ATP7B variant spectrum

Overall, 62 potentially pathogenic ATP7B variants, including 4 novel variants (Supplementary Fig. 1), were identified: 44 missense, 10 frameshift, 5 splice site, 2 nonsense, and 1 in-frame deletion (Supplementary Table 3). The variants were mostly distributed in TM5 and its adjacent areas (11, 17.74%), followed by the N-domain (9, 14.52%), P-domain (8, 12.90%), and the region around TM6 (8, 12.90%) and TM4 (7, 11.29%) (Fig. 2). The most common variant was R778L (allele frequency: 17.68%), followed by A874V (10.61%), V1106I (9.09%), P992L (6.57%), R919G (5.56%), and T935M (5.05%) (Fig. 2). There were 91 patients (91.92%) with two potential disease-causing variants, 7 patients (7.07%) with one potential disease-causing variant, and 1 patient with no variant. A summary of patient genotypes is outlined in Supplementary Table 4.

ATP7B variants were visualized in relation to the ATP7B protein regions. The number of alleles for each variant is displayed in brackets, and the most common variants are depicted in light blue with their number of alleles and allele frequencies displayed in brackets.

Genetic differences and diagnostic implications

Compared with those of patients with an onset age less than 35 years, the allele frequencies of A874V (A-domain/TM5, exon 11), V1106I (N-domain, exon 15), R919G (TM5, exon 12), and T935M (TM5, exon 12) were significantly greater in late-onset patients, whereas the allele frequencies of R778L (TM4, exon 8), PTV, and P992L (TM6, exon 13) were significantly lower (Fig. 3a). Accordingly, there was a greater allele frequency of variants in the A-domain/TM5 junction region, TM5 domain, and N-domain of ATP7B and a lower allele frequency of variants in the TM4 and TM6 domains (Supplementary Fig. 2a); as well as a greater allele frequency of variants in exons 11, 12, and 15, and a lower allele frequency of variants in exons 8 and 13 (Supplementary Fig. 2b) in patients with late-onset disease. Notably, of the patients with two potential variants identified, approximately 39.56% (36/91) of the patients carried one variant of A874V, V1106I, R919G, or T935M in combination with R778L (21/33), PTV (8/17), or P992L (7/12), and there was no homozygote of R778L, the most common genotype in China (Fig. 3b).

a Comparison of allele frequencies of common ATP7B variants between patients with late- and early-onset WD. The p value was adjusted by the Benjamini–Hochberg method and indicated as follows: NS, not significant (adjusted p > 0.05); *, adjusted p < 0.05; **, adjusted p < 0.01; ***, adjusted p < 0.001. b Characterization of ATP7B variant combinations in patients with late- and early-onset WD. c Correlations between ATP7B variant allele frequencies in the East Asian population and those in 1302 Chinese patients with WD.

According to gnomAD, there are comparable allele frequencies of T935M, R778L, and V1106I, as well as R919G, P992L, A874V, and I1148T, in East Asian populations (Supplementary Table 5). However, no homozygotes of V1106I, R919G, or T935M, nor compound heterozygotes of V1106I/T935M, V1106I/R919G, T935M/A874V, or T935M/R919G were identified in our 1237 early-onset and 99 late-onset patients (Fig. 3b), implying an inexplicit pathogenicity of these variant combinations or overlooking patients with these genotypes under the current diagnostic criteria. On the assumptions that R778L, P992L, A874V, V1216M, I1148T, M769H-fs, N1270S, and S975Y have 100% penetrance and that there is Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, we constructed a regression line based on the allele frequencies of these variants in gnomAD and our consecutive cohort of 1302 patients6. We found that variants T935M, V1106I, S518S, E1293K, G869R, L1083F, and D196E deviated significantly from the regression line (Fig. 3c), indicating a lower penetrance or nonpathogenicity of these variants.

Correlation between ATP7B variants and the WD phenotype

The current data suggest a relationship between the variants A874V, V1106I, T935M, and R919G and the late onset of WD, as well as a correlation between R778L, P992L, and PTV and the early onset of WD, among which A874V, R778L, P992L, and PTV were confirmed in our previous study6. We evaluated the distribution frequencies of V1106I, T935M, and R919G in our previous consecutive cohort (n = 1302)6. The results indicated that the allele frequencies of V1106I and T935M increased with increasing age at onset, whereas variant R919G, although exhibiting the highest allele frequency in patients aged more than 35 years, did not show a clear trend (Supplementary Fig. 3). According to univariate logistic regression, a neurological presentation was associated with age at onset (odds ratio [OR]: 1.026, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.009–1.044, p = 0.004) and the V1106I variant (dominant; OR: 0.374, 95% CI: 0.178–0.786, p = 0.009) but not with the R919G or T935M variant. Multivariate analysis revealed that age at onset (OR: 1.035, 95% CI: 1.016–1.054, p < 0.0001) and V1106I variant (OR: 0.240, 95% CI: 0.108–0.533, p < 0.0001) were independent factors associated with neurological presentation in patients with WD (Table 3).

Discussion

Patients with WD may become symptomatic at any stage of life, with most reported symptoms occurring between the ages of 5 and 3516. According to our consecutive cohort of 1302 patients, approximately 92.70% (1207/1302) of Chinese patients with WD develop symptoms under the age of 30 years, 2.84% (37/1302) of the patients had symptomatic onset between 35 and 39 years old, and only 2.15% (28/1302) of the patients became symptomatic at ≥ 40 years old (Supplementary Table 6). The percentage of patients with an onset age ≥ 40 years old is significantly lower than those of European patients13,17. In Europe, a symptomatic onset age of 40 years has been set as the cut-off age for late-onset WD, resulting in 3.8% or 8% of patients being classified as having late-onset WD13,17. Considering that the majority of Chinese patients with symptomatic WD have an onset age under 30 years old and that there is a 4.5-year difference in onset age between patients with neurological manifestations in China (19.3 ± 8.0) and Europe (23.8 ± 9.1)3,6, we chose an onset age of 35 years as the cut-off age for late-onset WD. Based on these criteria and our large WD database (n = 2132), 105 patients (4.92%) were included, which facilitated our investigation of the clinical and genetic characteristics of late-onset WD.

In the present study, most patients with late-onset WD presented with neurological symptoms, and there was a greater proportion of hepatic presentation patients exhibiting liver cirrhosis, which is consistent with the findings of a recent study in France17. In East Asia, a predominance of male patients in the WD cohort has been observed in several studies6,18,19,20; however, we identified comparable numbers of male and female patients with late-onset WD. As less estrogen may be secreted in older patients, our data support the hypothesis that it plays a protective role21. Overall, 97 index patients were diagnosed based on K–F rings, serum ceruloplasmin levels, and extrapyramidal symptoms/abnormal brain MRI, and 2 of the patients were diagnosed based on additional 24 h urinary copper. Our data showed that 97.91% (94/96) of patients with late-onset WD had ceruloplasmin concentrations lower than 0.2 g/L, and 95.96% (95/99) of the patients had positive K–F rings, highlighting their role in diagnosing late-onset WD. However, the serum ceruloplasmin levels were significantly greater in the older onset patients (Table 2), and abnormal brain MRI could only be identified in 48.28% of patients with hepatic presentations; additional laboratory data, such as 24 h urinary copper, should help establish the diagnosis. In total, 91.92% of the index patients (91/99) were genetically diagnosed with two potentially pathogenic variants, and 7.07% of the patients (7/99) had one potentially pathogenic variant, with a total of 62 variants identified. As large hemizygous deletions, variants within the promoter, 3′ untranslated region, and far intronic regions of ATP7B have not been screened, not all variants may have been detected in the current cohort.

The top six most common variants were R778L, A874V, V1106I, P992L, R919G, and T935M in the late-onset cohort, which displayed significant differences in allele frequencies compared to those in patients with early-onset WD. Our data strongly suggest that A874V, V1106I, and T935M are associated with late-onset WD, with V1106I and T935M exhibiting low penetrance. According to gnomAD, the V1106I and T935M variants exhibit allele frequencies comparable to those of R778L in the East Asian subpopulation, and there is also a high allele frequency of R919G. However, there were no homozygotes of V1106I, T935M, or R919G identified in multiple large Chinese cohort studies6,19,22,23, and there were also no variant combinations of A874V/T935M, V1106I/T935M, V1106I/R919G, or T935M/R919G identified in the present study (Fig. 3b). The absence of these variant combinations in patients with WD implies that they may be nonpathogenic or that patients with these genotypes may be overlooked due to atypical clinical features. However, this conclusion was established based on several premises. One concern is that the genetic background of the East Asian subgroup in gnomAD may not represent the Chinese population, as there are differences in hotspot variants among different regions of China6. Other issues include a lack of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, the relatively small number of patients with late-onset WD included in the current study, and the limited number of patients with WD with acquired genetic information; therefore, these results should be confirmed in more patients with WD.

Our previous data support the conclusion that R778L, PTV, and P992L are associated with the early onset of WD, and the current data indicate that approximately 58.06% of these variants (36/62) occurred in combination with A874V, V1106I, T935M, or R919G in patients with late-onset WD. Additionally, we found that two patients carried a variant combination of R778L and PTV (R778L/L1395P-fs and R778L/V937G-fs), where L1395P-fs (c.4183dup, exon 21) was located at the end of ATP7B, and V937G-fs (c.2810del, exon 12) was reported to cause exon 12 skipping during ATP7B pre-mRNA processing24. Moreover, the alternative splice variant of ATP7B encodes a protein that lacks the entire TM5 domain and retains 80% of the biological activity of the wild-type protein, thereby eliminating the influence of the disease-causing variant in exon 1224, which may play an important role in the mild symptoms of WD. Variants R919G and T935M are also located in exon 12, and in vitro experiments have indicated that the T935M variant exhibits a trafficking pattern similar to that of wild-type ATP7B under copper pressure, which is distinct from that of the R778L, R919G, and P992L variants25. Notably, the R919G variant has also been shown to cause exon 12 skipping26, which may explain the higher allele frequency of the R919G variant in late-onset patients and raises speculation about the role of T935M and other exon 12 variants in the alternative splicing of ATP7B.

We noticed that the K866–H880 region, where the G869R, A874V, A874P, and G875R variants are located, is not present in monkey ATP7B (Supplementary Fig. 4), implying that this region may not be important for ATP7B function. This region is located within the flexible loop between the TM5 and A domains, and the A874V variant still exhibits partial copper transport and ATP hydrolysis7. The destabilization and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention caused by ATP7B variants also play key roles in the pathogenesis of WD7. However, the A874V variant displays different characteristics from other ER retention variants, since inhibition of the p38/JNK pathway involved in the degradation of the H1069Q and R778L variants, and copper treatment in correcting G875R localization both failed to rescue the A874V variant9,27. Another intriguing region is the N-domain of ATP7B, as it displays little sequence homology to other P-type ATPase families but appears to share the same core nucleotide-binding structure28. There are four invariant residues (E1064, H1069, G1099, G1101) in P1B-type ATPases, and the V1106I variant is located near segment P1098-G1103, which is mostly affected by ATP binding28. Our data indicated that V1106I is negatively associated with the neurological presentation of WD, implying that patients carrying the V1106I variant may exhibit a low tendency to accumulate copper in the brain. The low penetration of the V1106I variant in patients with WD indicates weak damage to the ATP7B protein, and it is possible that a large number of patients carrying the V1106I variant may exhibit no or only mild WD symptoms.

In conclusion, the current study highlighted the value of K–F rings, serum ceruloplasmin levels, and extrapyramidal symptoms in the diagnosis of patients with late-onset WD and highlighted the correlation between variants A874V, V1106I, T935M, and R919G and the late onset of WD. However, we must realize that serum ceruloplasmin levels in patients with late-onset WD are significantly higher than those in patients with early-onset WD, and a large number of patients carrying homozygotes of V1106I, T935M, and R919G or compound heterozygotes of A874V/T935M, V1106I/T935M, V1106I/R919G, or T935M/R919G may be missed because of atypical or a lack of WD symptoms. Additionally, in the late-onset cohort, 27.42% (17/62) of the variants were located in the K866–H880 region, TM5 domain, and N-domain of ATP7B, and 71.72% of the patients (71/99) carried at least one variant from these regions, indicating that these may be hotspot areas involved in the late presentation of WD. Our research revealed distinct clinical and genetic characteristics of patients with late-onset WD, which may provide valuable insights into the genetic basis and diagnosis of this disease.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui University of Chinese Medicine and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals on whom genetic testing were performed.

Patients and phenotype evaluation

In this single-center observation study, consecutive patients who sought for diagnosis and treatment of WD between August 2016 and September 2019, as well as patients with WD with an onset age of over 35 years between September 2019 and September 2022, were recruited from the Department of Neurology at the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui University of Chinese Medicine. Each patient had a Leipzig score of 4 or more16, and their detailed demographic and clinical characteristics, including sex, birthplace, age at onset, age at diagnosis, onset of symptoms, laboratory findings, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), if available, were recorded. As of September 2022, 105 patients (99 index, 6 siblings) with an onset age of over 35 years, including 68 patients (65 index, 3 siblings) who had been reported in our previous study (1302 index, 64 siblings) between August 2016 and September 20196, were selected (Fig. 1). Patients with an onset age less than 35 years between August 2016 and September 2019 were considered as early-onset cohort (n = 1237), and the total cohort of index patients collected between August 2016 and September 2019 was considered as consecutive cohort (n = 1302)6. The index patients were divided into hepatic, neurological, and asymptomatic subgroups based on the onset of symptoms, as previously described6. Liver disease staging of late-onset patients at diagnosis was classified according to the Child–Pugh grade (A, B, or C), and structural brain abnormalities, including focal hyperintensity lesions and atrophy, were investigated using brain MRI scans.

Genetic analysis

The ATP7B variants of the patients were sequenced and analyzed exon by exon using previously described primers and methods6. For ATP7B variant penetrance analysis, the allele frequencies of the variants in our consecutive cohort of 1302 Chinese patients were compared with the gnomAD allele frequencies of the East Asian subgroup (Fig. 1), assuming that the East Asian samples in gnomAD were a relevant background population of Chinese patients with WD.

Statistical analysis

All of the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for quantitative data and as numbers (n) and relative frequencies (%) for categorical variables. Subgroup differences were analyzed using Student’s t test for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical parameters. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed for factors associated with hepatic/neurological manifestations in the consecutive cohort of patients who were identified with two potential pathogenic ATP7B variants and onset with hepatic (n = 276) or neurological (n = 665) symptoms (Fig. 1)6. For the ATP7B variants (R919G, V1106I, and T935M), a dominant model was used, and the significant univariate analysis result of age at onset was adopted from a previous study6. Only factors that showed significant associations in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model. To control for type I errors caused by the multiple-hypothesis test, the p value was adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg method29, and the significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Responses