Reviewing MAESTRO-NASH and the implications for hepatology and health systems in implementation/accessibility of Resmetirom

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) (formerly non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)) is characterised by fat accumulation within the liver parenchyma thereby making it one of the steatotic liver diseases (SLD). MASLD is distinct in that there are clear metabolic proponents (obesity, hyperlipidaemia, type 2 diabetes (T2D)) in the absence of other secondary causes, including substantial alcohol intake (a separate classification exists for this – MetALD), medications or inherited metabolic conditions. In some individuals, steatosis is associated with cellular injury (ballooned hepatocytes) and lobular inflammation, representing a more necro-inflammatory variant – metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). An estimated 5.3% of adults worldwide are living with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH)1. The natural history of MASLD and MASH demonstrates that as liver fibrosis progresses, the incidence of both liver events, including progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and extrahepatic events such as cardiovascular complications and non-liver cancer increase2.

The regulatory milestone of licencing resmetirom on 14 March 2024, in the United States (US), represents a pivotal moment in the natural history of MASH3. In addition, positive data in Nov 2024 from a phase 3 result on semaglutide will likely further broaden the available treatment landscape4,5. The advent of a dedicated treatment option approved by the Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) for MASH offers significant opportunities and expert guidance exists on the implementation within the US healthcare system6. Yet, the intersection of several forces poses real-world challenges for hepatologists and medical specialists who manage the sequelae of metabolic dysfunction that must be understood and addressed, namely: (i) the biology of resmetirom itself; (ii) the general biophysical nature of MASH progression; (iii) the present realities within individual clinical settings, throughout health systems in the US, United Kingdom (UK) and among European Union (EU) member states, and associated payers; (iv) patient-specific attributes; (v) real-world efficacy of non-pharmaceutical interventions for liver health outcomes; and (vi) social and commercial determinants of the disease.

We also note several emerging themes that invite further reflection and, in some cases, additional research or possibly further updates to treatment and care guidelines: (i) for diagnosis, limitations with current biomarkers for active case finding of adults under the age of 35 living with often undiagnosed at-risk MASH; (ii) for patient-specific treatment and care, the role of alcohol and the degree of management of diabetes; (iii) for gastroenterologists and hepatologists, the need to understand recent and forthcoming updates to relevant guidelines, combined with the opportunity for focused training, education and skills-building; and (iv) drawing from learnings in the US, the benefit of a deepened understanding of health systems operational readiness for steatotic liver disease generally, and MASH specifically, in parallel with anticipated mutual recognition approvals of resmetirom across Europe.

Biology of resmetirom, physiology of fibrosis progression, and biophysical target effects

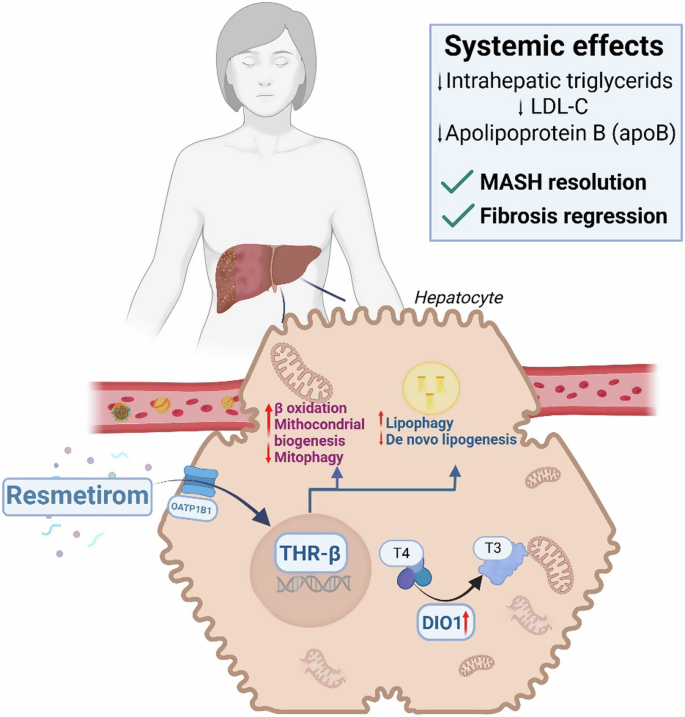

Resmetirom is a thyroid hormone mimetic which represents a novel liver-directed treatment as an agonist for thyroid hormone receptor-beta (THR-β) (Summarised in Fig. 1). THR-β is present in the anterior pituitary, hypothalamus, cochlea, brain, retina, heart and bone; however, the long-term effect of resmetirom agonism on these sites is not well understood. The selective activation of THR-β in liver tissue minimises off-target effects and interactions with thyroid hormone receptor alpha (THR-α)7,8.

This leads to enhanced β-oxidation of fatty acids, increased mitochondrial biogenesis, and mitophagy, while concurrently reducing de novo lipogenesis and promoting lipophagy. DIO1 Iodothyronine Deiodinase 1, OATP1B1 Organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1, THR-β thyroid hormone receptor-β, T3 triiodothyronine, T4 tetraiodothyronine.

It is important in appreciating the natural history of MASLD including the risk of both fibrosis progression and regression, which confers varying risk, both liver-related and extra-hepatic in nature9. Over the past 30 years, our understanding of MASH has evolved, with increased recognition of genetic and environmental factors driving its development. Advances in understanding MASH pathogenesis have led to new insights, improved diagnostic approaches, and increasingly precise treat-to-target pharmacotherapies. Despite promising preclinical results, many of these potential MASH treatments have failed to achieve the requisite surrogate endpoints advocated by the US FDA, EU European Medicines Agency (EMA) (See Table 1) and UK Medicines or Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). The reasons are numerous and have been expertly summarised elsewhere. The prevalence of metabolic co-morbidities, e.g., T2D, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and obesity are rising dramatically worldwide; therefore, it is increasingly recognised that the management of MASLD and MASH remains intrinsically linked to the treatment of the composites of metabolic syndrome (MetS) and their shared cardiometabolic risks, given that these remain10.

Exploring the MAESTRO-NASH trial data

Both primary endpoints were achieved in the two treatment arms of resmetirom (80 mg and 100 mg) at week 52. Resolution of MASH was seen in 25.9% with 80 mg and in 29.9% with 100 mg resmetirom in comparison to 9.7% with placebo (p < 0.0001 for both treatments). A significant difference was also seen with an improvement of one or more fibrosis stages in 24.2% with 80 mg and 25.9% with 100 mg resmetirom compared to 14.2% with placebo (p < 0.0001 for both treatments)7.

The treatment response ranged from 24.0% to 30.0% with resmetirom and the delta between treatment and placebo for MASH resolution was 16.4% in 80 mg and 20.7% in the 100 mg group at 52 weeks. For fibrosis regression by at least one histological stage, the treatment effect delta was 10.2% for 80 mg and 11.8% in the 100 mg group. This translates into a clinical benefit for approximately 2 of 10 patients in the trial, and 1 of 10 patients treated with resmetirom to have MASH resolution or fibrosis improvement, respectively8,9. As indicated by the number needed to treat (NNT) with a dose of 100 mg resmetirom, an average of 5 and 8.5 patients would require treatment for one additional patient to have the outcomes MASH resolution (NNT 5.0) or fibrosis regression by one stage (NNT 8.5), respectively.

MAESTRO-NASH is an ongoing trial that assesses the superiority of the two trialled doses in terms of progression to cirrhosis, all-cause mortality, and liver-related events (LRE) at 54 months. It will require post-approval studies (phase 4) to determine the effect size on other outcomes (e.g., cardiovascular; cancer) in this patient population living with MASH, as the number of patients enrolled in MAESTRO-NASH is not high enough to observe differences within the duration of the phase 3 trial.

It is important for regulatory and payer bodies to devise relevant NNT data in qualifying quality adjusted life years (QALYs) and cost estimates; however, the extrapolation of NNT for MASH resolution and fibrosis regression within MAESTRO-NASH likely represents an over-estimation of benefit at this point. Therefore, it remains to be seen if there is sufficient LRE reduction within the phase 4 trial at final read-out. This is especially true when considering real-world benefit over the relatively self-selecting populace within an randomised control trial (RCT) setting.

A key secondary endpoint was the reduction of LDL cholesterol at 24 weeks, which showed a significant difference between 80 mg (−13.6%) and 100 mg (−16.3%) resmetirom compared to placebo (0.1%, p < 0.0001). Similar findings were also noted for other lipids and lipoproteins. These additional effects may reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, a benefit for individuals with MASH who often face significant metabolic challenges, in which CVD predominates all-cause mortality.

Resmetirom’s effects on liver histology and atherogenic dyslipidaemia were independent of weight. However, a separate post-trial analysis of the data took note of a higher efficacy of 100 mg compared to 80 mg resmetirom in achieving both primary endpoints in the group of patients ≥100 kg9,11. In the trial, resmetirom had a neutral effect on both body weight and insulin sensitivity. This emphasises the importance of concomitant non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs; e.g., nutrition, physical activity); adjunct NPIs are likely to further augment and enhance treatment response.

Resmetirom was overall well tolerated in terms of safety. Diarrhoea was more common with resmetirom (80 mg, 27.0%; 100 mg, 33.4%) compared to placebo (15.6%). Adverse events leading to trial discontinuation were slightly higher in those receiving 100 mg (7.7%) than 80 mg (2.8%) resmetirom and placebo (3.4%)7. Within the prescribing licence, dosage adjustment is recommended for those on concomitant statins with periodic monitoring for statin-related adverse reactions including elevation of liver enzymes, myopathy, and rhabdomyolysis12.

Overall, however, there was no major difference among serious adverse events (SAE) seen between resmetirom and placebo. These data are additionally supported by the MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 trial that was specifically designed to investigate the safety profile of resmetirom in adults with MASLD and presumed MASH13. The primary endpoint incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events over 52 weeks was not different between both treatment arms and placebo, while diarrhoea and nausea were more commonly seen with resmetirom.

The MAESTRO-NASH trial is a pivotal juncture in MASH drug development, being the first phase 3 trial to reach both endpoints required for conditional regulatory approval and demonstrating the feasibility of conducting such a large trial with liver histology as per the pre-defined endpoint for efficacy. In future, the outcomes of the ongoing MAESTRO-NASH trial are eagerly awaited and the combination of approved drugs in the blinded study population could further reveal the potential of combination therapies (e.g., with incretins)14,15,16. In addition, the group of patients living with compensated cirrhosis – which constitutes the greatest unmet need and highest health care costs – will need to be addressed. Here, outcomes of the MAESTRO-NASH-OUTCOMES trial could lead the way17.

Real World experience and challenges from the Trial’s design

To NIT or to biopsy?

A key facet of the MAESTRO-NASH trial design was the adoption of non-invasive tests (NITs) in parallel to histological endpoints, enhancing its diagnostic approach. This innovative development should inform future efforts to move beyond histology as the de-facto standard for MASH trial endpoints. It also allows the adoption of NITs to identify those likely to benefit without requiring liver biopsy prior to prescription of resmetirom. Notwithstanding this, certain U.S. governmental payer administrations, such as the U.S. Veterans Administration (USVA), appear to be requiring biopsy prior to access resmetirom, thus mandating histology as a requirement for treatment18.

One of the unmet challenges in the implementation of NIT biomarkers centres on their discriminant ability, particularly for those < 35 and > 65 years. The FIB-4 test was developed in a cohort of individuals between 35 and 65 years of age and forms the initial fibrosis assessment of many recommended pathways19. Yet we recognise that it has been observed to perform less well with those < 35 years20,21, as age is a confounding variable. While it has been possible to adjust for increasing age, with a FIB-4 cut off of ≥ 2 in those > 65 years22, this is not possible in younger individuals given the propensity to increase false positives with the FIB-4 test. It is those younger patients living with MASH with predisposing risk who are likely to benefit the most in terms of both reduced early mortality risk and longer-term improved quality of life from early identification, stratification and intervention, yet are unlikely to be positively identified being “at-risk”. This is especially important when considering fibrosis progression rates in those with MASH (approximately 7 years/stage), and the opportunity to at least halt progressive fibrogenesis, in addition to inducing fibrosis regression in those before significant fibrosis develops (F ≥ 2)23. This aspect also relates to reimbursement of testing and can vary between medical systems and public vs private payers.

Current biomarker utility is problematic as it exploits high negative predictive values for use in low-prevalence populations (e.g., primary care), and often utilises age as a composite (e.g. FIB-4)21. Age adjusted variants are available for those >65 (again for FIB-4); however, even use of more advanced blood-based biomarkers [e.g., Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) test] often reflect age-related bias with advancing age and can result in a substantial number of false-positive test results. Development of sequential testing strategies using “rule-in” thresholds looks to mitigate some of these shortcomings. Such innovative pathways are pivotal as they should allow the positive identification of individuals “at-risk” with likely F2-F3 fibrosis, who are the target population for the use of resmetirom.

It is important to consider the performance of NITs within the MAESTRO-NASH trial. The mean FIB-4 scores were relatively low across both MASH F2 (1.3+/-0.64) and F3 (1.5+/-0.72). This is clearly of less utility in an enhanced population of metabolically-diseased patients (of which a significant proportion had T2D). In turn, vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) or ELF were more reflective of the actual fibrosis stage in those with MASH F3 with mean values of 14.4 ± 6.8 (kPa) and 9.9 ± 0.88, respectively. However, it is important to note that participants in MAESTRO-NASH were pre-selected using a VCTE cut-off >8.5 kPa. Nevertheless, utilising NITs, including VCTE or ELF, may aid in appropriate case finding for the use of resmetirom. If these NITs can be used for assessing treatment response requires further evidence from the ongoing MAESTRO-NASH trial after 54 months.

An important consideration of the preparedness for UK and EU member state health systems is development of improved biomarkers and diagnostics consensus, advancing toward a standardised approach for patient identification and inclusion, allowing for prevention and treatment. Further, we call to MHRA and EMA’s attention that Europe is already pathfinding via several EU funded projects, including LITMUS, LIVERScreen, GRIP-on-MASH, and LIVERAIM24.

Key considerations for hepatology from MAESTRO-NASH

The interface between fibrosis, type 2 diabetes and metabolic risk optimisation

Liver fibrosis is the key histological determinant in determining the prognostic outcomes of chronic liver disease, and MASLD and MASH in particular25,26. Firstly, we need to consider fibrosis in the context of T2D, because recruitment stratification was based on the presence/absence of T2D and fibrosis stage. Fibrosis stage is relevant because it represents the sequelae of altered natural hepatic parenchyma, typified by the presence of pathological collagen deposition within the extra-cellular matrix, often accompanied by vascularised septae. Fibrogenesis is a dynamic process, intertwined with repetitious injurious and reparative responses. Within the MAESTRO-NASH cohort, almost 5% of individuals had fibrosis stage 1B, while almost a third had F2 fibrosis, and the remaining ~60% were F3.

T2D is a recognised as a strong potentiator of fibrogenesis in MASH. Insulin resistance is the most potent pathogenic potentiator, which promotes a pro-inflammatory state, with increased lipolysis, de-novo lipogenesis and free-fatty acid flux. Consequent advanced glycation end-products (AGE), oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and hepatic stellate activity are relevant pathophysiological sequelae27,28.

Prospective cohorts of patients living with T2D with unknown MASLD status, demonstrated rates of advanced liver fibrosis of 14%, and cirrhosis of 3–6%. Patients living with MASH and T2D have a higher likelihood of more rapidly progressive fibrosis development with estimates of fibrosis progression rates (FPR) as little as every four years29.

Consequently, adults living with MASH and T2D will more likely progress to liver cirrhosis, decompensated liver disease, thus have a higher risk of liver-related mortality30. The co-existence of MASLD with T2D increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) twofold, and risk of death from HCC 1.5-fold compared with MASLD without T2D31. The data around “prediabetes” or “impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)” in relation to MASLD remains sparse, although a comprehensive meta-analysis of outcomes related to IGT suggested a link with HCC with worse associated prognosis (it did not explore development of fibrosis or cirrhosis explicitly)32,33. Importantly, up to 50% of those with T2D or prediabetes remain undiagnosed globally. This compounds concerns that the majority of those with significant metabolic dysfunction, including MASLD and MASH, remain undiagnosed34.

Close attention should be paid to pre-existing pharmacotherapeutics in the context of potentially prescribing resmetirom. While acknowledging the importance of T2D in fibrosis progression, the MAESTRO-NASH trial design imposed specific criteria for participants with diabetes, who comprised ~70% of the study population. Interestingly, the mean A1c was 6.6%, which demonstrates adequate glycaemic control highlighting the progressive nature of MASH even in those with controlled diabetes. The applicability of these findings to real-world populations with significantly worse glycaemic control remains uncertain. Is there therapeutic benefit for those persons with MASH with poorly controlled diabetes, given the potentiation of T2D in driving fibrogenesis? Ongoing tight glycaemic control will be important in those with T2D treated with resmetirom. Real-world data are needed to see how fastidiously this is enforced and the effect on glycaemic variance.

Both the trial design and this limited U.S. real world experience further prompt the practical question of where resmetirom will ultimately fit within the clinical treatment arsenal, especially when compared to ‘off-label’ therapies currently being tested in MASH-specific trials, including positive findings from the ESSENCE study4,35. In the context of T2D, we note with particular interest MAESTRO-NASH’s criteria for GLP-1s and statins: Glucagon-like peptide 1 [GLP-1] agonist therapy (e.g., albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, lixisenatide, semaglutide) unless stabilised for 24 weeks prior to biopsy. GLP-1 therapeutics may not be initiated, or doses increased during the first 52 weeks of the study.

Extending to other cardiometabolic risks that may also bear upon distinct or combination therapies, MAESTRO-NASH’s criteria for statins and/or other lipid-lowering therapies mandated that doses of these concomitant medications were to be established for at least 6 weeks prior to anticipated randomization. Statins were also to be taken in the evening for at least 2 weeks prior to randomization. While there is no evidence for statins in fibrosis regression, there is clear evidence of their efficacy in lipid improvement. There appears to be an additive interaction between resmetirom and several statins. An increase in exposure of atorvastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin and simvastatin was observed when concomitantly administered with resmetirom, which may increase the risk of adverse reactions related to these drugs7.

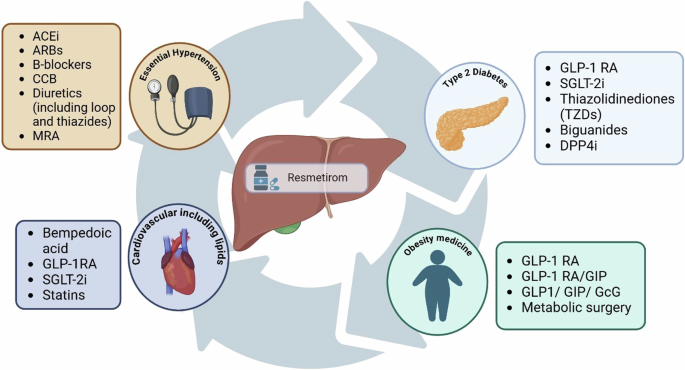

Therefore, we pose a critical question: how can hepatologists collaborate effectively with primary care physicians, and other metabolic-based specialists to optimise comprehensive, coordinated care for patients living with MASH, leveraging each specialty’s expertise in optimizing relevant comorbidities? This approach may involve advocating for continued or augmented treatment, or implementing combination therapies that offer potential synergistic or pleiotropic effects, such as GLP-1 RAs, dual agonists, statins or anti-hypertensive medication to optimise patient outcomes, and address multiple composites of the disease, particularly in relation to cardiovascular outcomes. It requires further guidance on comprehensive models of care, and integrated co-ordinated management of MASH and metabolic disease as a wider continuum, rather than individual, distinct entities (Fig. 2)36.

ACEi Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors, ARBs Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers, B-blockers Beta blockers, CCB Calcium Channel Blockers, DPP4i Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor; GcG Glucagon; GIP Gastric Inhibitory Polypeptide, GLP-1RA Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists, MRA Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists, SGLT-2i Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor.

Alcohol

The inclusion/exclusion criteria on alcohol use in MAESTRO-NASH are of important note for physicians when considering real-world efficacy and actual practice with their patients. MAESTRO-NASH retrospectively assessed participants for a history of significant alcohol consumption, specifically looking for patterns lasting more than three consecutive months within the year preceding the screening process. Significant alcohol consumption was defined as equal to or greater than approximately 2 alcoholic drinks per day for males, and approximately 1.5 alcoholic drinks per day for females.

This reinforces the importance of accurately recording a patient’s alcohol consumption, including longitudinal assessment37. Notwithstanding this, we know from other contexts that ~30% of the patients labelled as living with MASLD may have been more accurately categorised as living with MetALD (not MASLD) based on blood and urinary alcohol metabolites38. There is clear synergism, and differing progression in those with steatohepatitis with MetALD and increased risk of fibrosis progression and consequent decompensation39.

We recognise that individuals living with MetALD represent a substantial proportion of individuals with SLD in the real world: should we consider offering resmetirom treatment to them, or should we intensify efforts on combination therapies targeting specific pathophysiological processes targeting steatosis, fibrogenesis, or pro-inflammatory effects? A group of patients with possible MetALD was identified in the MAESTRO-NASH trial based on carbohydrate deficient transferrin or PETH testing and their response to resmetirom was compared to those with pure MASH. In the 75 (9.6%) of patients with possible MetALD, the response rates to resmetirom were 29–35% for NASH resolution and 30–35% for fibrosis improvement, similar to those without MetALD40.

The role of alcohol for patients living with MASH remains an important research priority. A salutary tale can be found in the metabolic-surgery domain, whereby an increase in alcohol use disorder (AUD) and ArLD has been identified in persons having undergone metabolic surgery for presumed MASLD. Recent studies have suggested that a significant proportion of those with presumed MASLD more probably have MetALD, which was not identified pre-operatively. Conversely, however, metabolic surgery may invoke fluctuations in GLP-1R and leptin which pre-disposes to “binge” behaviour changes substituting eating with harmful drinking instead41.

Clinicians should also stay alert to ‘drop out’ characteristics among presenting patients. Dropout rates were generally consistent with what is typically observed in clinical trials of this nature, with gastrointestinal side effects being the most common cause of discontinuation in the higher dose group. Like GLP-1 RAs, patient adherence may be enhanced by counselling about side effects prior to drug initiation to set expectations. Some patient-specific characteristics may mirror those of the trial’s ‘dropouts’ who otherwise met inclusion criteria while others were due to side-effects profiles. In terms of bedside manner, when prescribing resmetirom it may be pragmatic to note the possibility of discontinuation up front with patients. Within the trial’s dropouts, in addition to gastrointestinal side-effects, we also note the following as potentially relevant in communication with patients including risk of gallbladder-related events and increased risk of statin-related myopathy and myositis12.

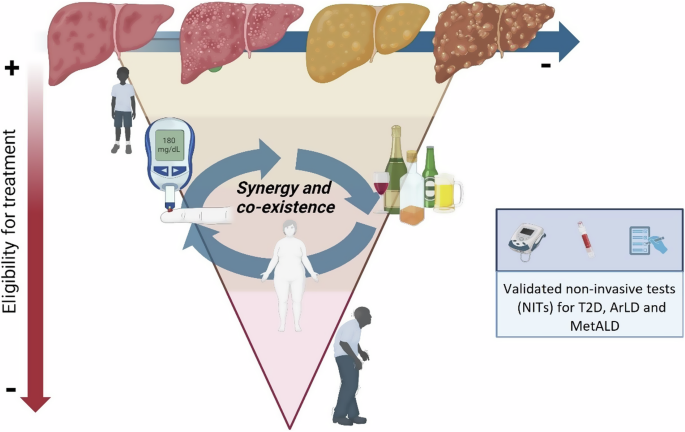

The trial’s exclusion criteria may also be relevant in clinical practice. An important part of the RCT design within MASH relates to the relatively stringent inclusion criteria. Of note, children, women of childbearing age (not willing to take contraception, considering pregnancy, or those pregnancy or currently breast-feeding), people living with HIV, and patients with type 1 diabetes were all excluded. Therefore, it is imperative that real-world data is available to inform decisions around extension to these groups (Fig. 3).

Comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, and alcohol consumption, which often coexist in SLD and potentiate fibrosis progression. Older age, multimorbidity, and fibrosis progression rates may influence the medical decision to prescribe the drug. T2D type 2 diabetes, ArLD Alcohol-related Liver Disease, MetALD Metabolic dysfunction and alcohol-related liver disease.

Pairing with non-pharmaceutical interventions

We note, with interest, the plain language in the first sentence of the FDA’s approval release contemplates resmetirom is “to be used along with diet and exercise,” two key NPIs. In the MAESTRO-NASH trial, patients across all groups received nutritional and exercise counseling in accordance with the 2018/2023 AASLD Practice Guidance recommendations, which advocated for weight loss through a hypocaloric diet and nutritional modification (daily reduction of 500 to 1000 kilocalories), either alone or in combination with moderate-intensity exercise42,43. Notwithstanding the inclusion of counseling, unfortunately, NPI-specific data is not available for further evaluation of their patient-specific effects from the published trial results44. Following approval, the combination of NPIs and resmetirom received minimal attention in a July 2024 expert panel’s recommendations on practical clinical applications for initiating and monitoring resmetirom. In fairness to the panel, to date, the MASH community of practice lacks data regarding the potential synergistic effect between MASH generally, and resmetirom specifically, and NPIs. Moreover, we understand resmetirom is not, at present, packaged with a patient care self-help guide or something of similar effect to support implementation of NPIs in MASH treatment and care in the US44.

As resmetirom approaches regulatory review for approval, particularly in the context of universal coverage through public health systems in the UK and most EU member states, we expect the MHRA and EMA to carefully evaluate its efficacy within comprehensive treatment models, and its real-world effectiveness based on US data. These models are likely to incorporate NPIs, emphasizing physical activity, nutrition, and potentially cognitive behavioural therapies, to optimise a holistic approach to MASH management and optimise patient outcomes. We were unable to delineate from the MAESTRO-NASH data whether or how these aspects were considered. We observe persistent vagueness around the FDA recommendations in relation to NPI implementation and monitoring.

We anticipate, however, that some evidence may be published in advance of MHRA and EMA final decisions. In addition to the regulatory review process, we also recognise the lack of attention to the FDA’s specific language, which may introduce risks that US payers may impose further barriers to the uptake of needed pharmacotherapeutics for persons living with MASH.

The specific context within some EU member states also presents opportunities for rethinking task-shifting in the context of NPIs, with hepatology prescription of resmetirom paired with nurse care, educational and patient assessment interventions in a standarcised language (Nursing Interventions Classification)45,46, aligned with NPIs (e.g., weight management, weight reduction assistance or health education) (Supplementary table 1), perhaps presents a unique opportunity to prescribe and/or monitor prescribed NPIs– not fully available, outside mid-level providers (including advanced nurse practitioners (ANPs), physician assistants or associates (PAs)and advanced practice providers (APPs)), in the US. In the vacuum between general practitioner and specialist clinicians, nurses in some EU member state health systems provide more holistic non-pharmaceutical interventions. This may represent an underutilised aspect of treatment and care on behalf of patients living with MASH.

While nurse prescribing powers are certainly not specific only to persons living with MASH, examples of the nurse prescription of care interventions align quite well with the FDA approval language to create multi-disciplinary models of person-centered treatment and care. Moreover, the standarcised registry coding could further lend itself to building an evidence base for these patients. It remains to be seen if nurses will be independently authorised to prescribe NPIs for patients prescribed resmetirom independent of specialist physician oversight, or within a comprehensive multidisciplinary team structure observed in other liver-specific pharmacotherapies.

A note on determinants of health

While not specifically discussed in the trials, health professionals should also consider structural, social and commercial determinants of health for a successful implementation of resmetirom. Socially deprived communities often face higher rates of liver-related risk behaviours (e.g., poor diet, physical inactivity, tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking) due to economic inequality, lower education levels, and limited access to healthcare, insufficient supply of care, and lower healthcare literacy, all of which hinder the ability to make and sustain healthy choices47,48,49,50. While it is not possible in a clinical setting to address all aspects of determinants of health, we believe it is possible to address some of these barriers and thereby develop person-centred, targeted strategies to optimise equitable access to health interventions48,51. Importantly, we also recognise that people who are broadly impacted by determinants of health are often under-represented in trial cohorts, so real-world effectiveness may vary accordingly across social gradients.

Health systems policy and payer implications

The momentum generated by resmetirom, combined with NPIs, holds significant promise for improving health outcomes, which should be confirmed in clinical trials and real-world settings. This synergy may drive further advancement of NPIs and bolster public health initiatives, which are crucial in safeguarding future generations from the growing SLD public health threat. This, in turn, presents the possibility in the future for greater specificity in MASH guidelines for resmetirom (and possibly future approved drugs) with a range of NPIs. Prescribing clinicians, of course, neither can, nor should wait, for a roll-out trial before treating and caring for those patients living with MASH who need treatment and care post haste48,52.

We also anticipate challenges in health systems regarding referral pathways due to the introduction of new drug treatment options. However, we recognise that launching promising treatments without robust support from health systems and clear reimbursement policies from payers’ risks exacerbating existing inequities. Greater clarity and consistency are required, particularly regarding QALY assessment thresholds and payer benchmarks. It is important to recognise that QALY thresholds should consider active case finding in individuals under 35, as steatotic liver disease, including MASH, increasingly affects younger populations. This trend mirrors the rising prevalence of other related conditions, such as T2D and obesity, among younger demographics53.

Publicly available evidence from real-world examples in the US via the Veterans Administration (VA) includes their inclusion criteria language for resmetirom: “Non-cirrhotic metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) with METAVIR F2–F3 fibrosis and non- alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score (NAS) greater than or equal to 4 on liver biopsy in the past 36 months. This begins to reveal comparisons between aspects of the combined MAESTRO trials (e.g., NITs) and real-world payer requirements (e.g., VA). This dissonance in criterion creates a challenging landscape for patients, with concerns regarding the widening of healthcare inequalities36. We also note that UK & EU health systems, ultimately, are likely to adapt to paired drug and nutrition and/or exercise NPIs, in part due to cost and in part for integrated, patient-centred care. It remains to be seen whether they implement a histological initiation point.

Education, skills building and training in advance of active case finding

Resmetirom approval presents a number of important developmental aspects for hepatologists. Specifically, these include structured continuing medical education (CME), increased awareness of policy development, and operationalisation components including implementation and scalability of active case finding. These pivots are important instructional elements in developing opportunities for hepatologists with advent of novel treatment. An opportunity for resmetirom is the development of a comprehensive, accessible educational programme for hepatologists, endocrinologists, and relevant allied health professionals.

Despite these challenges, there is a significant opportunity to increase disease awareness among a broader range of clinicians, and by extension, patients. This is particularly relevant in primary care settings but also extends to specialties dealing with MASLD-related multimorbidity, such as cardiology, endocrinology/diabetology, internal medicine, and specialists in lipid disorders, obesity, and cardiovascular medicine. Increasing awareness across these specialties will lead to more comprehensive and integrated patient care, particularly with the advent of directed liver therapies.

There is undoubted disconnect in how international guidelines propose positive diagnostic criteria and screening approaches for fibrosis. Currently, however, there is a lack of clear consensus and approach in the implementation of these strategies. There are exemplars of practice that have been implemented with success, and we would urge policy-makers and specialty societies to develop more concrete approaches to achieving this in partnership with key stakeholders in primary care, in particular.

Priorities for near-term further research

In furthering our understanding of the implications of resmetirom in clinical practice there is a need for longitudinal cohort studies, using electronic health record (EHR) chart review of patients living with T2D who are prescribed resmetirom alongside other diabetes medications which may offer some hepatic benefit, e.g. GLP-1 RAs, SGLT2 inhibitors, and pioglitazone in addition to understanding putative beneficial synergistic effects in both MASH and other metabolic comorbidities. It will be important to capture a diverse patient population to assess the variability in treatment responses, patient acceptability and adherence. From a safety perspective, more robust data assessing the effect of resmetirom in patients living with thyroid disease, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, thyroid nodules will be particularly relevant.

Additionally, the long-term effects on resmetirom on the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis remains an important focus. Such analyses will incorporate real-world economics and outcomes assessments to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of resmetirom. This can also include analyses of healthcare resource utilization, quality-adjusted life years, and payer reimbursement policies in the short to medium term.

Finally, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), including thorough validated measures, are imperative to understand patient perspectives on treatments, and should form an important composite in any comprehensive evaluation programme. Understanding patient perspectives on a novel treatment offers important insights to regulators, payers and pharmaceutical companies. It may highlight common themes in acceptability to patients, as well as association with commonly occurring side-effects. As the first licenced therapy for MASH, it will provide unique insights into the self-reported quality of life changes that a novel therapeutic provides19.

Conclusion

The clear advantage following the US FDA approval of resmetirom in early 2024 is the availability of the first targeted drug therapy specifically for MASH. It is a unique opportunity to enhance and expand treatment and care options for patients otherwise at risk for further progression to cirrhosis and HCC.

In parallel, key risks must be addressed, particularly recognising and addressing the roles of sound T2D management, weight management, reduction of cardiovascular risk, and reduction or abstinence of alcohol consumption. Yet for similar outcomes to be achieved in other regions of the world, gastroenterologists and hepatologists outside of the United States must also gain access to expanded drug treatment options. The most immediate challenge preceding the expected UK and EU approvals in 2025 is for regulatory agencies to make their own appraisals of resmetirom, including in the context of paired prescription of NPIs. If achieved, then the broad opportunity emerging from the limited available US experience is to improve real-world outcomes for the many hundreds of thousands of people living with MASH around the world.

Responses