Role of VEGFA in type 2 diabetes mellitus rats subjected to partial hepatectomy

Introduction

Liver damage induced after a warm ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) period is clinically relevant since it is unavoidable in major liver surgeries, such as liver transplantation (LT)1 or partial hepatectomy (PH)2, and it is usually accompanied by regenerative and hepatic failure3,4. Among patients that require PH + I/R, more than 20% present steatosis, a prevalence which is expected to increase in the future as are other related metabolic disorders, like type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)5,6,7. It has been reported that metabolic disorders related to hepatic steatosis are associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality after major liver resections8,9,10. This fact makes the study of these pathologies in the context of PH + I/R a scientific and clinical necessity.

T2DM is a progressive and chronic metabolic disease defined by a chronic state of hyperglycemia due to a loss of insulin function characterized by insulin resistance and an increase of insulin in the blood. This condition may eventually advance into a higher degree of insulin resistance and a decrease in insulin secretion due to the loss of β-cell mass provoked by overstimulation, thereby worsening metabolic impairment11,12. Moreover, it has been reported that insulin is an important hepatotrophic factor in cell culture13,14 and in experimental models of hepatic resections15,16. In fact, T2DM has a negative influence on surgical risks and postoperative outcomes in clinical PH8,17; for instance, Li et al. concluded that the presence of T2DM increases the risk of postoperative complications. Moreover, according to results obtained in the same systematic review, based on 16 observational studies with almost 16,000 subjects, T2DM is clearly related to poor outcomes in patients undergoing PH: it increases the rate of liver failure and decreases survival after liver surgery. In addition, the study reports increased hospital stays for these patients8. However, to our knowledge, no preclinical studies have examined PH + I/R in a T2DM model. Furthermore, the underlying mechanisms by which the presence of T2DM negatively affects postoperative outcomes in PH + I/R remains unclear.

Among the family of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs), VEGFA is the most studied and is involved in cell survival and proliferation via binding to vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2)6,18,19,20. Previous studies of experimental models of obesity-induced genetically, using the same surgical conditions as those evaluated in the current study, indicated that exogenous VEGFA in lean (Ln) Zucker rats protected non-steatotic livers against the injurious effects of PH under I/R in terms of damage and regenerative failure. However, the administration of exogenous VEGFA to obese (Ob) Zucker rats reduced hepatic VEGFA following surgery. This was because of the high levels of soluble VEGFR1 (sFlt1) in circulation, which bound to VEGFA, and, consequently, the VEGFA could not reach the liver to exert its beneficial effects. This was demonstrated by the concomitant administration of VEGFA and an antibody against sFlt1, which protected steatotic livers against the deleterious effects induced by surgery, resulting in reduced damage and improved liver regeneration4. Moreover, in a preclinical model of hepatic resection, the inhibition of MMP9 in the liver increased the activity of VEGFA and this was associated with an improvement in liver regeneration via the recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells from the bone marrow21.

Given all these observations, the primary aim of the present study was to elucidate the potential role of VEGFA in a preclinical model of PH under vascular occlusion in the presence of T2DM. This requires characterization of the experimental model of PH + I/R with T2DM which must also mimic clinical conditions as closely as possible, in order to maximize the potential for knowledge transfer to the clinical setting. Since we had promising results in previous preclinical rat models of PH under vascular occlusion in Ln and Ob rats4, we considered whether similar strategies aimed at regulating VEGFs could also be beneficial in the presence of T2DM under the same surgical conditions, utilizing the same well-established rat models of T2DM22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29.

The physiological properties and anatomy, as well as the lobular architecture of rats, are more similar to those of humans (hepatocyte arrangement, structure of sinusoids, and bile ducts, among others) than are those of other potential models (particularly, mice)30. This is crucial since the current study is based on hepatic resection and the potential use of our results in developing clinical therapeutic options. Moreover, rats also have metabolic characteristics that are relatively close to those of humans, such as glucose, insulin resistance, and lipid metabolism31; rats develop obesity and insulin resistance that is similar to the human version; and rats with T2DM show associated complications such as fatty infiltration or fibrosis, commonly observed in diabetic patients. In addition, we ruled out the possibility of using mice since they may not fully reflect the complexity and variability of all aspects of T2DM in humans; consequently, their response to pharmacological treatments may differ from that of humans, thus limiting their application in a clinical setting. There are also other factors reported in the literature that negatively affect the reproducibility of any results using T2DM mice and which complicate the interpretation of experimental outcomes. Among different factors, compared to mice, the response of rats to immune system challenges, infections, inflammation, and injury in general is more similar to that of humans32,33,34.

We, therefore, decided to maintain the same species (rats) as in previous work4, under identical surgical conditions (PH under 60 min ischemia, closely mimicking clinical practice), to determine whether the effects of VEGFA observed in steatotic and non-steatotic livers4 vary depending on the presence of T2DM. This approach minimizes confounding factors and misinterpretations of the effects of specific drugs in relation to the type of liver due to interspecies variability and it supports accurate interpretations of preclinical data.

At the same time, different studies indicate that VEGFA might develop synergic functionality together with VEGFB, as in the promotion of angiogenesis in an infracted heart35; whereas the two play a balancing role in the regulation of different processes, such as revascularization, energy metabolism or thermogenesis in both white and brown adipose tissue6,36. Moreover, both VEGFA and VEGFB protect against damage in ischemic diseases including heart failure and cerebral ischemia37,38,39. In addition, it has been reported that VEGFB may have effects on the survival of various cell types such as cardiac, nerve or vascular cells40,41,42,43,44, and that it promotes endothelial survival, as well as antioxidant effects: both essential for liver regeneration44. Meanwhile, the involvement of VEGFs in T2DM should also be considered; their effects have been discussed as either positive or negative in both clinical and preclinical studies45,46,47,48.

Therefore, considering these aspects, we studied the potential changes in the levels of VEGFB and its role in PH under vascular occlusion in rats with T2DM; and whether the involvement of intestine and/or adipose tissue might explain the potential changes in VEGFA and VEGFB levels in liver. This is because: two-way communication between the liver and intestine has been described as crucial in many liver pathologies and hepatic surgeries49; during PH under I/R, different mediators are released from adipose tissue into circulation50; and VEGFs play a crucial role in regulating vascularization in adipose tissue36,51. The results derived from this research could be of considerable scientific and clinical interest and help establish protective strategies suitable for application in PH under I/R in the presence of T2DM, as well as in recipients of LT with T2DM.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (9 to 10 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River (Paris, France). All procedures were approved by the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Barcelona and by the Generalitat de Catalunya (DAAM 9353). European Union regulations (Directive 86/609 EEC) for animal experiments were respected. As previously described, a model of type 2 diabetes without hyperinsulinemia was induced. This is a well-established rat model of T2DM22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 (the reasons are explained below). For this, rats were fed a high-fat diet (D12451, Research Diets Inc., New Brunswick, NJ), containing 45% kcal as fat. Then, 8 weeks later, these rats received a single dose of Stz (30 mg/kg body weight i.p.) diluted in 0.1 M, 4.5 pH of citrate buffer. Blood glucose was evaluated 96 h later using glucose oxidase reagent strips (Aviva Accu-Chek; Roche, Mannheim, Germany); rats with blood glucose levels over 350 mg/dL were considered diabetic. The non-diabetic group (No-Db) was fed a regular rat chow (Teklad Global 14% protein rodent maintenance diet, ENVIGO). Then, 8 weeks later, these rats received the vehicle (1 mL of citrate buffer 0.1 M, 4.5 pH i.p.), and blood glucose was evaluated 96 h later, as described above. Based on Oil Red Staining, T2DM rats showed severe liver steatosis (60–Sprague–Dawle70%), no apparent liver damage (evaluated by H&E staining), and no signs of fibrosis (evaluated by Sirius Red Staining). Moreover, the rats exhibited high levels of glucose and no changes in the levels of insulin in the blood, as reported in previous studies22. Signs of liver damage, steatosis, and fibrosis were not present in non-diabetic rats (see Supplementary Fig. 1). One week after the Stz injection (Db group), the rats were subjected to PH under I/R (PH + I/R), as described below, and blood glucose was also measured prior to the surgery to confirm the diabetic status.

The reasons for using a model of type 2 diabetes without hyperinsulinemia are as follows. T2DM is a chronic and progressive disease11,12,52. In the prediabetic stage, frequently associated with obesity, there is an increase in insulin resistance compensated by the increase in the production of insulin, resulting in normoglycaemia and hyperinsulinemia11. However, if not treated, the prediabetic stage can progress to T2DM, wherein insulin production is insufficient to compensate the insulin resistance, leading to an impaired insulin response and chronic hyperglycemia12. Moreover, the chronic overstimulation of pancreatic beta cells to produce insulin provokes a reduction in the beta cell mass, leading to normoinsulinemia or, eventually, hypoinsulinemia, and worsening the pathological condition11. Therefore, in this paper, a rat model with hyperglycemia and normoinsulinemia, which is associated with an advanced stage of type 2 diabetes, was established22,53 to study the effects of this disease during major liver surgery, such is PH + I/R.

Experimental groups

Protocol 1: To evaluate the role of VEGFA and VEGFB in T2DM livers subjected to PH under vascular occlusion:

-

1.

Sham (n = 6). Animals with type 2 diabetes, but without surgery, as described in the animal section. Hepatic hilar vessels of animals were dissected.

-

2.

PH + I/R (n = 6). Animals with type 2 diabetes were subjected to 70% PH under 60 min ischemia. After anesthesia with isoflurane, the left hepatic lobe was resected. Afterward, a microvascular clamp was placed on the portal triad (which supplies the median lobe) for 60 min to induce partial ischemia. Bowel congestion was prevented by allowing portal flow through the right and caudate lobes. After the ischemic period of 60 min, the right and caudate lobes were removed, and the clamp was released to permit reperfusion of the median lobe54

-

3.

PH + I/R + VEGFA (n = 6). As in Group 2, but treated with 5 μg/kg i.v. VEGFA (100-20-100 UG; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

-

4.

PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2 (n = 6). As in Group 2, but treated with 2.5 mg/kg i.v. Vandetanib (orb61120; Biorbyt, Cambridge, UK), an antagonist of VEGFR2.

-

5.

PH + I/R + VEGFB (n = 6). As in Group 2 but treated with 5 μg/kg i.v. VEGFB (100-20B-100 UG; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

The animals in Protocol 1 were killed by exsanguination; tissue and plasma samples were collected after 4 h of reperfusion. Blood was collected through the infrahepatic inferior cava vein. The blood was centrifuged at 4 °C and at 3000 rpm for 15 min; plasma was collected just after centrifugation; plasma and tissue were immediately frozen at −80 °C.

The conditions of this study (PH under 60 min ischemia and 4 h reperfusion) were established on the basis of the results of previous studies and preliminary results from our group55,56. The reperfusion time is within the range in which we observe peak hepatic damage parameters and these reperfusion times also permit high survival rates. Furthermore, our preliminary results indicate that after 4 h reperfusion, we see significant mortality; all diabetic rats died within 24 h of surgery. So, we strategically determined this reperfusion time point at which peak liver damage has been induced but survival rates are high, and repair mechanisms, such as increases in Ki67 and PCNA expression, have been triggered. This critical time point (4 h of reperfusion) documented in numerous high-impact surgical papers4,50,54,57, not only highlights differences in liver injury but also in regeneration processes. Repairing mechanisms are triggered at different intervals depending on organ type, liver condition, surgical conditions, drug efficacy, and other factors; and it is essential to consider this fact. Therefore, these experimental conditions were the most appropriate and vital for our experimental aims of evaluating the effect of VEGFA on damage and investigating the signaling pathways activated by VEGFA in PH under I/R with T2DM.

The doses of the different drugs were determined from previous studies4 and our preliminary results, as detailed in what follows.

Protocol 2: To evaluate whether the beneficial effects of VEGF on healthy livers subjected to PH under vascular occlusion are also observed in the presence of T2DM, the following experimental groups with healthy livers were added. This enabled us to select the appropriate doses of the different drugs to administer to T2DM livers:

-

6.

Sham (No-Db) (n = 6): non-diabetic rats with the hepatic hilar vessels dissected.

-

7.

PH + I/R (No-Db) (n = 6): non-diabetic rats submitted to a 70% partial hepatectomy under 60 min ischemia, exactly as described for Group 2 above.

-

8.

PH + I/R + VEGFA 2 µg/kg i.v. (No-Db) (n = 6): As in Group 2, but treated with 2 μg/kg i.v. VEGFA (100-20-100 UG; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

-

9.

PH + I/R + VEGFA 5 µg/kg i.v. (No-Db) (n = 6): As in Group 2, but treated with 5 μg/kg i.v. VEGFA (100-20-100 UG; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

-

10.

PH + I/R + VEGFA 10 µg/kg i.v. (No-Db) (n = 6): As in Group 2, but treated with 10 μg/kg i.v. VEGFA (100-20-100 UG; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

-

11.

PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2 1 mg/kg i.v. (No-Db) (n = 6): As in Group 2, but treated with 1 mg/kg i.v. Vandetanib (orb61120; Biorbyt, Cambridge, UK), an antagonist of VEGFR2.

-

12.

PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2 2.5 mg/kg i.v. (No-Db) (n = 6): As in Group 2, but treated with 2.5 mg/kg i.v. Vandetanib (orb61120; Biorbyt, Cambridge, UK), an antagonist of VEGFR2.

-

13.

PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2 5 mg/kg i.v. (No-Db) (n = 6): As in Group 2, but treated with 5 mg/kg i.v. Vandetanib (orb61120; Biorbyt, Cambridge, UK), an antagonist of VEGFR2.

-

14.

PH + I/R + VEGFB 2 µg/kg i.v. (No-Db) (n = 6): As in Group 2 but treated with 2 μg/kg i.v. VEGFB (100-20B-100 UG; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

-

15.

PH + I/R + VEGFB 5 µg/kg i.v. (No-Db) (n = 6): As in Group 2 but treated with 5 μg/kg i.v. VEGFB (100-20B-100 UG; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

-

16.

PH + I/R + VEGFB 10 µg/kg i.v. (No-Db) (n = 6): As in Group 2 but treated with 10 μg/kg i.v. VEGFB (100-20B-100 UG; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

Protocol 3: To confirm that the administration of VEGFA to healthy livers using the same surgical procedures (PH under 60 min ischemia) and 4 h of reperfusion, and the same pre-treatment times and dose of VEGFA that were used for T2DM rats lead to VEGFA signaling being effectively transduced within 4 h of reperfusion. To achieve this objective, we used the samples from Groups 6, 7, and 9 (Protocol 2).

The animals from Protocols 2 and 3 were killed by exsanguination, and tissue and plasma samples were collected after 4 h of reperfusion. Blood was collected and processed as described in Protocol 1. Plasma and tissue were immediately frozen at −80 °C.

Biochemical determinations

Plasma transaminases: alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured using standard procedures (ALT: GNV41125 and AST: GNV40125 from RAL, Barcelona, Spain).

Total bilirubin, insulin, and sFlt1 were measured in plasma using immunosorbent commercial assay kits (total bilirubin: MBS730053; sFlt1: MBS732055 from MyBioSource, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA; insulin: 90060 from CrystalChem Inc., Elk Grove Village, IL, USA).

For tissue analyses, the total protein concentration was quantified by the colorimetric Bradford method, in order to adjust the posterior determinations.

For immunoenzymatic assays, 200 mg of the tissue was homogenized in 1.5 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 1× at pH 7 using a Polytron homogenizer for 60 s. The samples were then centrifuged at 5000×g and 4 °C for 15 min; the supernatant was collected and the samples were stored at −80 °C.

Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) and vascular endothelial growth factor B (VEGFB) were determined in the liver, adipose tissue, and intestine using immunoassay kits (VEGFA: E-EL-R2603 from Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China; VEGFB: MBS269676 from MyBioSource, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA)

Finally, activity of caspase 3 (C3), activity of caspase 8 (C8), activity of protein kinase C (PKC), DNA-binding protein inhibitor (ID1), interleukin 1 beta (IL1β), interleukin 10 (IL10), antigen Ki-67 (Ki67), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), protein kinase B alpha (PKBα or AKT) and wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 2 (Wnt2) were determined in liver (C3: ab39401; C8: ab39700; Il1β ab100768 from Abcam, Cambridge, UK; PKC: ADI-EKS-420A from Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA; IL10: E-EL-R0016 from Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China; PI3K: CSB-E08418r from Cusabio, Wuhan, China; and ID1: MBS1604796; Ki67: MBS705024; PKBα: MBS761144, and Wnt2: MBS8807293 all from MyBioSource, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

To assess oxidative stress, hepatic levels of lipid peroxidation were quantified by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) using the thobarbituric acid reaction58. Two hundred micrograms of frozen tissue samples were homogenized in 2 mL of Tris buffer at pH 7. For protein precipitation, 0.25 mL of 50% trichloroacetic acid was added to 0.25 mL of the homogenate. After mixing, it was centrifuged at 3000×g for 15 min at 4 °C. Then, 0.25 mL of 0.67% thiobarbituric acid solution was added to the supernatant and the mix was boiled for 15 min. After cooling, the optical density of the samples was measured at 530 nm59.

To assess neutrophil accumulation, hepatic myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels were quantified photometrically using 3, 3’, 5, 5’ tetramethylbenzidine as a substrate60,61. 200 mg of liver samples were homogenized in phosphate buffer (0.06 M KH2PO4, pH 6) that contains 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HTAB), followed by sonication for 30 s at 20% power. The samples then underwent three freeze-thaw cycles in dry ice and water and were incubated for 2 h at 60 °C to inactivate non-specific peroxidases and MPO inhibitors that could affect the assay. After incubation, the samples were centrifuged for 12 min at 4000×g and 4 °C; the supernatant was collected. Then, 10 μL of tetramethylbenzidine reagent dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a concentration of 5 mg/mL was added to 10 μL of the supernatant. At time 0 (t = 0), 70 μL of phosphate buffer (8 mM KH2PO4, pH 6) containing 0.05% H2O2 was added, and MPO enzymatic kinetics were determined, measuring absorbance for 10 mins starting every consecutive minute at a wavelength of 630 nm. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme necessary to produce an increase of one absorbance unit per minute58.

Reverse transcription and quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from 30 mg of frozen rat liver and intestine sections using TRIzol reagent (15596026 from Invitrogen, Madrid, Spain) and was quantified with a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer. Two µg of RNA was reverse transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (4374966 from ThermoFisher Scientific, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Real-time PCR was performed in an ABI PRISM 7900 HT detection system by using 10 µL of TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix (4304437 from ThermoFisher Scientific, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in a total of 20 µL amplification mixtures, containing 100 ng of reverse-transcribed RNA.

Premade Assays on Demand TaqMan probes were utilized (Rn01511602_m1 for VEGFA, Rn01454585_g1 for VEGFB, and Rn00667869_m1 for β-actin, from ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol). Relative quantification was performed by the ΔΔCt method. Β-actin was used as an endogenous control. Data for the gene expression studies were calculated by comparing the relative expression of the cDNAs obtained from the mRNAs in the surgical groups compared with the expression in the Sham groups. Relative values are presented in the graph in a per-unit format.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Paraffine-embedded liver sections were used for staining with hematoxylin and eosin, Sirius Red, and histological analyses of TUNEL and PCNA. OCT liver sections were used to study liver steatosis by Red Oil Staining.

To assess the extent of liver damage, sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin were examined using a point-counting technique on an ordinal scale as follows: grade 0, minimal or no signs of injury; grade 1, mild injury characterized by cytoplasmatic vacuolation and localized nuclear pyknosis; grade 2, moderate to severe injury featuring widespread nuclear pyknosis, heightened cytoplasmatic eosinophilia, and disruption of intercellular boundaries; and grade 3, severe necrosis accompanied by hepatic cord disintegration, hemorrhaging and infiltration of neutrophils62. This is explained in Supplementary Material, Table 1. Liver damage point-counting process.

Steatosis in the liver was evaluated by red-oil staining on frozen specimens according to standard procedures. Sirius Red staining was performed to observe collagen I fibers as markers of fibrosis.

A TUNEL assay kit was utilized to detect apoptotic cells (nuclei or apoptotic bodies) via a DNA fragmentation detection kit (ab206386 from Abcam, Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

To analyze liver regeneration, immunohistological analyses were performed with Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA). After fixation with 4% formalin/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the samples were immunostained with an antibody, anti-PCNA (DAKO, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Then, slices were stained with DAB and counterstained with hematoxylin.

The tissue samples were examined and photographed with an Olympus BX51 microscope, and DP74 camera (Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan). Image processing was performed using FijiImageJ.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.0.2 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). The results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The statistical significance of different variables was determined via ANOVA. If the test showed significant differences (p ≤ 0.05), a posterior Tukey test was performed. For the comparisons between only two groups, a Student’s t-test was performed. The results were considered significantly different at p values ≤ 0.05.

Results

In non-diabetic SD rats subjected to PH + I/R (PH + I/R (No-Db)), reduced levels of VEGFA and VEGFB were observed in the liver, compared with the results of the Sham group (Sham (No-Db)). To evaluate the relevance of the reduction in these VEGFs induced by the surgery, different doses of VEGFA, anti-VEGFR2, and VEGFB were administered to achieve the same levels of VEGFA and VEGFB as those observed in the Sham group. Our results show that administration of VEGFA at 2 μg/kg i.v. did not significantly alter hepatic VEGFA levels, which remained similar to those of the non-diabetic PH + I/R (No-Db) group. By increasing the doses of VEGFA administered to 5 μg/kg and 10 μg/kg i.v., we observed increases in the hepatic VEGFA levels of the PH + I/R + VEGFA (No-Db) groups, compared with the non-diabetic PH + I/R (No-Db) group. At 5 μg/kg (Fig. S2), hepatic VEGFA levels were similar to those in the non-diabetic Sham (No-Db) group. Similar results were obtained when VEGFB was administered at a dose of 5 μg/kg (Fig. S4). All of these data agreed with the hepatic damage results. Indeed, the administration of either VEGFA or VEGFB at a dose of 2 μg/kg did not induce any changes in the hepatic damage parameters, compared with the results of the non-diabetic PH + I/R (No-Db) group. In contrast, a dose of 5 μg/kg i.v. of either VEGFA or VEGFB reduced hepatic damage, compared with the results of the non-diabetic PH + I/R (No-Db) group and similar protection was observed when the dose of either VEGFA or VEGFB was increased (10 μg/kg, i.v.) (Figs. S2 and S4). Thus, the dose of VEGFA and VEGFB selected for the current study was of 5 μg/kg i.v. Regarding the establishment of the correct dose of anti-VEGFR2 (Fig. S3), the minimum dose necessary to induce changes in AST and ALT in non-diabetic rats (PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2 (No-Db)) was observed to be 2.5 mg/kg i.v. Taking all of these results into account, we evaluated whether the beneficial effects of VEGFs observed in healthy livers subjected to PH under vascular occlusion (at the selected dose: 5 μg/kg for VEGFA and VEGFB; 2.5 mg/kg for anti-VEGFR2) are also evident in PH + I/R in the presence of T2DM. All of our results presented below focus on PH + I/R in the presence of T2DM.

As shown in Fig. 1a, the levels of VEGFA in the liver after PH + I/R were drastically reduced when compared with the Sham group. Exogenously administered VEGFA reached the liver, as shown by the increases in hepatic VEGFA of the PH + I/R + VEGFA group compared to those of the PH + I/R group. As expected, the administration of an antagonist against VEGFR2 (PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2) did not induce changes in the levels of VEGFA when compared to the PH + I/R group.

a VEGFA protein concentration in the liver after PH + I/R was determined by ELISA. Hepatic damage after PH + I/R. **Sham vs PH + I/R, *PH + I/R vs PH + I/R + VEGFA. b Hepatic damage; AST levels in plasma after PH + I/R. ****Sham vs PH + I/R, ***PH + I/R vs PH + I/R + VEGFA. c Hepatic damage; ALT levels in plasma after PH + I/R. **Sham vs PH + I/R, *PH + I/R vs PH + I/R + VEGFA. d Hepatic damage; Bilirubin concentration in plasma after PH + I/R determined by ELISA. *PH + I/R vs PH + I/R + VEGFA. e Hepatic damage; H&E staining of liver sections and damage score at 4× (scale bar corresponds to 500 µm) after PH + I/R. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; ****p ≤ 0.0001. The number of samples is n = 6 for each group corresponding to the different sections (a–e).

Next, the relevance of the changes in VEGFA induced by PH + I/R for damage and regenerative failure was investigated.

Administration of exogenous VEGFA (PH + I/R + VEGFA) exacerbated hepatic damage, compared with the results of the PH + I/R group, since it resulted in increases in AST, ALT, and high levels of bilirubin (this latter is a parameter that indicates poor liver functionality) (Fig. 1b–d). In line with this, no improvements in the parameters of necrosis damage score were observed when compared with the results of the PH + I/R group. Next, the role of endogenous VEGFA was also evaluated by administering an antagonist of VEGFR2 (PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2). Our results indicate no significant differences in hepatic damage, functionality (AST, ALT, and bilirubin), or histological lesions when compared with the PH + I/R group (Fig. 1b–e).

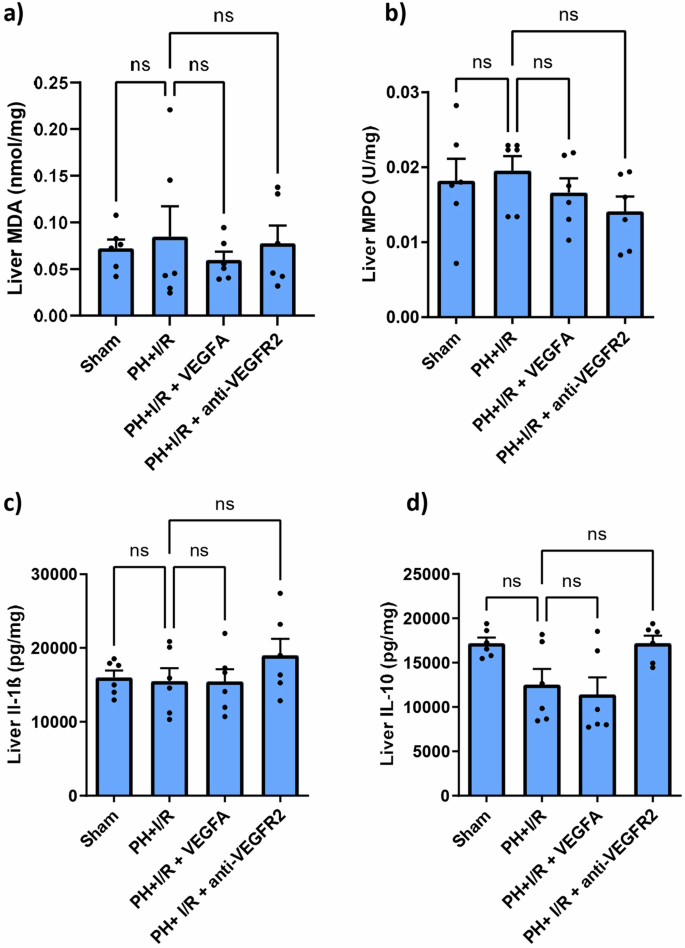

In agreement with the results for hepatic damage, the pharmacological modulation of VEGFA (PH + I/R + VEGFA and PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2) did not ameliorate inflammatory parameters (Fig. 2). Similarly, oxidative stress (measured via MDA), neutrophil accumulation (measured via MPO) and pro- and anti-inflammatory ILs (IL-1β and IL-10, respectively) were of the same order as those in the PH + I/R group.

a MDA concentration in the liver after PH + I/R. b MPO activity in the liver after PH + I/R. c IL1β concentration in liver after PH + I/R determined by ELISA. d IL10 concentration in liver after PH + I/R determined by ELISA. No significant differences were observed between the different groups regarding any of the parameters evaluated. The number of samples is n = 6 for each group corresponding to the different sections (a–d).

In contrast to necrosis parameters (which are of the same order or even exacerbated compared to PH + I/R) (Fig. 1b, c, and e), the administration of exogenous VEGFA (PH + I/R + VEGFA) did not induce changes in apoptotic cell death (Fig. 3a–c). Indeed, the levels of caspases 3 (Fig. 3a) and 8 (Fig. 3b) and the TUNEL results (Fig. 3c) were similar to those for the PH + I/R group. In addition, endogenous VEGFA had no effect on apoptosis, since the inhibition of VEGFR2 (PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2) resulted in apoptotic parameters of the same order as those in the PH + I/R group.

a C3 activity in the liver after PH + I/R determined by a colorimetric assay. *Sham vs PH + I/R. b C8 activity in the liver after PH + I/R was determined by a colorimetric assay. *Sham vs PH + I/R. c TUNEL staining in liver sections at 20× to detect apoptosis (scale bar corresponds to 100 µm) after PH + I/R. The arrow points to apoptotic nuclei. *p ≤ 0.05. The number of samples is n = 6 for each group corresponding to the different sections (a–c).

Regarding the parameters for liver regeneration (evaluated by Ki67 and PCNA), a reduction in both markers was observed in the PH + I/R group, compared with the results of the Sham group (Fig. 4). The administration of exogenous VEGFA (PH + I/R + VEGFA) resulted in the same degree of liver regenerative failure as without this administration (PH + I/R): liver regeneration parameters were of the same order in the PH + I/R and PH + I/R + VEGFA groups. Interestingly, the inhibition of VEGFR2 (PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2) improved liver regeneration: this intervention resulted in increased Ki67 levels, compared with the PH + I/R group (Fig. 4a). In addition, the number of PCNA-positive cells was higher in the PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2 group than in the PH + I/R group (Fig. 4b).

a Ki-67 protein concentration in liver after PH + I/R determined by ELISA. ****Sham vs PH + I/R, ***PH + I/R vs PH + I/R+ anti-VEGFR2. b Immunohistochemical detection of PCNA in liver sections of T2DM rats subjected to PH + I/R at 20× (scale bar corresponds to 100 µm) and %PCNA-positive hepatocytes. ***p ≤ 0.001; ****p ≤ 0.0001. The number of samples is n = 6 for each group corresponding to the different sections (a, b).

Next, we investigated whether the effects of VEGFA on hepatic damage and regenerative failure might be mediated via ID1/Wnt2 (Fig. 5a, b) and PI3K/AKT (Fig. 5c, d): pathways involved in liver proliferation and recognized as the main VEGFA signaling pathways in liver surgery and isolated hepatic cells4,63,64. The pharmacological modulation of exogenous and endogenous VEGFA did not induce changes in the ID1/Wnt2 pathway (Fig. 5a, b). Indeed, the hepatic levels of ID1 or Wnt2 of the PH + I/R + VEGFA and PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2 groups were unaltered and similar to those of the PH + I/R group. However, the levels of PI3K/AKT were drastically reduced in the PH + I/R compared with the Sham group (Fig. 5c, D). The levels of PI3K/AKT in the liver were similar in the PH + I/R + VEGFA and PH + I/R groups. Meanwhile, an important increase in the levels of PI3K/AKT in the liver was found in the PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2 group when compared with the PH + I/R group.

a Concentration in the liver of the protein ID1 after PH + I/R determined by ELISA. b Concentration in the liver of the protein Wnt2 after PH + I/R determined by ELISA. c Concentration in the liver of the protein PI3K after PH + I/R determined by ELISA. ***Sham vs PH + I/R, *PH + I/R vs PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2. d Concentration in the liver of the protein AKT after PH + I/R determined by ELISA. **Sham vs PH + I/R, *PH vs PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001. The number of samples is n = 6 for each group corresponding to the different sections (a–d).

These results indicate that the improvement in liver regeneration observed when the action of endogenous VEGFA was inhibited is associated with increases in the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Thus, changes in this crucial signaling pathway would explain the injurious effect of endogenous VEGFA in surgery on T2DM livers. In contrast, the injurious effects of exogenous VEGFA in terms of hepatic damage cannot be explained by the main signaling pathways by which VEGFA exerts its effects (ID1/Wnt2 and PI3K/AKT).

Next, we evaluated whether VEGFA might induce changes in the levels of VEGFB in the liver. As shown in Fig. 6, no changes in hepatic levels of VEGFB were observed after PH + I/R, compared to those of the Sham group. Exogenously administered VEGFB reached the liver, since higher hepatic VEGFB was observed in the PH + I/R + VEGFB group than in the PH + I/R group. However, the pharmacological modulation of VEGFA (PH + I/R + VEGFA) did not modify hepatic levels of VEGFB, compared with the PH + I/R group.

a VEGFB protein concentration in the liver after PH + I/R was determined by ELISA. ****Sham vs PH + I/R, *PH + I/R vs PH + I/R + VEGFB. b Hepatic damage after PH + I/R; AST levels in plasma. ****Sham vs PH + I/R, **PH + I/R vs PH + I/R + VEGFB. c Hepatic damage after PH + I/R; ALT levels in plasma. **Sham vs PH + I/R. d Hepatic damage after PH + I/R; bilirubin levels in plasma determined by ELISA. e Hepatic damage after PH + I/R; damage score and H&E staining of liver sections at 4× (scale bar: 500 µm). *Sham vs PH + I/R. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ****p ≤ 0.0001. The number of samples is n = 6 for each group corresponding to the different sections (a–e).

The administration of VEGFB induced a significant increase in AST (and a non-significant tendency towards an increase in ALT) (Fig. 6b, c). Histological lesions in the PH + I/R + VEGFB group were similar to those of the PH + I/R group (see images and damage score, Fig. 6e). No improvements in liver functionality (determined by bilirubin) (Fig. 6d), apoptosis (caspases 3 and 8, and TUNEL assay) (Fig. 7a–c) or liver regenerative parameters (Ki67 levels and PCNA positive-cells) (Fig. 7d, e) were evidenced in the PH + I/R + VEGFB group, compared with the PH + I/R group. VEGFB administration (PH + I/R + VEGFB) did not improve either regeneration or liver damage markers. In fact, the levels of some hepatic damage parameters, such as AST, were higher than those found in the PH + I/R group after VEGFB administration (PH + I/R + VEGFB).

a Apoptosis after PH + I/R; C3 activity in liver determined by a colorimetric assay. *Sham vs PH + I/R. b Apoptosis after PH + I/R; C8 activity in liver determined by a colorimetric assay. *Sham vs PH + I/R. c Apoptosis after PH + I/R; TUNEL staining in liver section at 20× (scale bar: 100 µm). The arrow points to apoptotic nuclei. d Liver regeneration after PH + I/R; Ki-67 protein concentration in liver determined by ELISA. ****Sham vs PH + I/R. e Liver regeneration after PH + I/R; immunohistochemical detection of PCNA in liver section at 20× (scale bar: 100 µm). *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ****p ≤ 0.0001. The number of samples is n = 6 for each group corresponding to the different sections (a–e).

Finally, we evaluated whether the levels of VEGFA and VEGFB in the liver might be explained by the synthesis of these VEGFs in the liver or by contributions from the intestine or adipose tissue. The reduction in VEGFA levels observed in the liver after PH + I/R cannot be explained by changes in its production in the liver, since hepatic VEGFA mRNA levels in the PH + I/R group were similar to those of the Sham group (Fig. 8a). Similarly, intestine VEGFA protein levels in the PH + I/R group were similar to those of the Sham group (Fig. 8c). Interestingly, an increase in the protein levels of VEGFA was observed in adipose tissue of the PH + I/R group, compared with the Sham group (Fig. 8d). Since sFlt1 is capable of sequestering VEGFA in circulation and, thus, determining the levels of VEGFA in liver65,66,67 and considering that plasma sFlt1 levels are elevated in different liver diseases and liver surgeries4,68,69, we attempted to establish whether, in addition to the involvement of adipose tissue, the reduced VEGFA levels in the liver following surgery may be partially explained by potential differences in circulating levels of sFlt1. However, this was not the case: no differences in the levels of sFlt1 in plasma were observed between the Sham, PH + I/R, and PH + I/R + VEGFA groups (Fig. 8b).

a Expression of VEGFA mRNA in the liver after PH + I/R determined by qRT-PCR. b sFlt1 protein concentration in plasma determined by ELISA, after PH + I/R. c VEGFA protein concentration in the intestine after PH + I/R determined by ELISA. d VEGFA protein concentration in adipose tissue after PH + I/R determined by ELISA. **Sham vs PH + I/R. **p ≤ 0.01. The number of samples is n = 6 for each group corresponding to the different sections (a–d).

No changes in VEGFB protein levels were observed between the PH + I/R and Sham groups, but an increase in hepatic VEGFB mRNA levels was observed after surgery (Fig. 9a). In adipose tissue, no changes in VEGFB levels were observed between the PH + I/R and Sham groups (Fig. 9d); whereas a reduction in the mRNA and protein levels of VEGFB in the intestine were observed in the PH + I/R group compared with the Sham group (Fig. 9b, c).

a Expression of VEGFB mRNA in the liver determined by qRT-PCR, after PH + I/R. *Sham vs PH + I/R. b Expression of VEGFB mRNA in the intestine determined by qRT-PCR, after PH + I/R. **Sham vs PH + I/R. c VEGFB protein concentration in the intestine, after PH + I/R, determined by ELISA. ****Sham vs PH + I/R, *PH + I/R vs PH + I/R + VEGFB. d VEGFB protein concentration in adipose tissue, after PH + I/R, determined by ELISA. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ****p ≤ 0.0001. The number of samples is n = 6 for each group corresponding to the different sections (a–d).

Discussion

Herein, we show for the first time the effects of VEGFA/B in hepatic resection under vascular occlusion in the presence of T2DM, using a rat experimental model. The use of rats with T2DM is preferred over the use of mice as an experimental model for many reasons, as explained in the Introduction above and reported in the literature22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. Clearly, our goal is always to identify therapeutic targets and to avoid adopting models that do not align with clinical scenarios. Additionally, the size of the different organs/tissues in rats is larger than in mice70. This can be important when it comes to performing all the different analyses required, as rats provide more tissue and are easier to monitor. Furthermore, fewer animals may be required to achieve statistically significant results71,72. This is crucial according to national and international legislation related to ethics and safety and is duly accredited by the Clinical Research and Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee and the Biosecurity Committee, which are committed and adhere strictly to the 3 R’s.

In addition to the appropriate experimental model, we selected the best methods for each determination based on our objectives. Determining the concentration of Ki67 using the commercial ELISA method has been proven to be effective in numerous studies73,74,75,76. The commercial kit includes a standard at known concentrations (quantitative and objective method) which enables researchers to evaluate the regenerative parameter Ki67 in all groups of the corresponding study. The Ki67 concentrations determined by ELISA matched (followed the same pattern) the results of PCNA immunohistochemical analyses. Similar principles were applied to caspases: the kits we reference do indeed measure the activity levels of caspases 3 and 8.

Regarding PI3K/Ki67, we measured total levels, not their phosphorylated forms, as under our conditions, total PI3K/Ki67 provides a more stable and consistent perspective, and more information than phosphorylation status. Total PI3K/AKT provides insight into both the regulation of its expression over time and the potential responsiveness of cells to future stimuli. It reflects baseline expression within cells, indicating the potential capacity for this signaling pathway to respond to stimuli and initiate different signaling pathways and thereby maintain essential cellular functions. In contrast, phosphorylated PI3K/AKT indicates immediate activation. In disease states, alterations in total PI3K expression can signify dysregulation of PI3K signaling pathways77,78; increased total PI3K levels may indicate a compensatory mechanism in response to chronic stimulation or disease progression79,80.

We found that different mechanisms are triggered and maintain VEGF levels low in the liver and counteract its injurious effects. Our objective was to evaluate whether the inhibition of the action of VEGFA was associated with increased Total PI3K/AKT as a compensatory mechanism to trigger the corresponding signaling pathway, depending on the stimulus, and provide insight into long-term regulation. Similarly, the low Total PI3K/AKT observed after the surgical procedure (without any treatment: pathological liver subjected to PH + I/R and in the presence of T2DM) indicates the poor capacity of the liver to respond to stimuli/stress and the impossibility of maintaining crucial signaling pathways (Total PI3K/AKT) that would counteract the adverse conditions. In our case, the benefits of VEGFA inhibition were associated with high Total PI3K/AKT and improved liver regeneration.

Of scientific and clinical interest, this is the first preclinical study to report hepatic damage and liver regenerative failure in PH under vascular occlusion and in the presence of T2DM. We characterize a preclinical PH + I/R model in the presence of T2DM that closely mimics clinical conditions, since the poor tolerance of livers subjected to PH under vascular occlusion in the presence of T2DM is associated with poor postoperative outcomes and with high mortality rates in patients8. Our results herein showing high 24-h mortality after surgery on livers with T2DM (100% within 24 h of reperfusion) indicate that the presence of T2DM is a crucial risk factor when livers are subjected to PH under vascular occlusion. Our previous results4,54 indicated 90% and 70% survival of healthy animals and obese animals with simple steatosis, respectively, 14 days after PH under vascular occlusion. Liver resection mortality rates in diabetic patients are notably high8, and they agree with our observations in the rat model used here.

In this same surgical context, in a model of PH + I/R with and without steatosis, a different role of VEGFA was previously reported. Exogenous VEGFA administration in Ln Zucker rats protected non-steatotic livers from the harmful effects of PH under I/R. However, in Ob Zucker rats, exogenous VEGFA resulted in a decrease in VEGFA levels after surgery due to the high levels of circulating soluble VEGFR1 (sFlt1), which bound to VEGFA, preventing it from reaching the liver where it could exert its protective effects. Thus, a combination of VEGFA with anti-sFlt1 was required to protect steatotic livers during PH under vascular occlusion4. In contrast with those previous results in the same surgical conditions, herein we show for the first time that, in the presence of T2DM, livers subjected to PH + I/R have reduced VEGFA, in relation to the Sham group, and that exogenously administered VEGFA (PH + I/R + VEGFA) reaches the liver: hepatic VEGFA was higher than in the PH + I/R group. In addition, we observed no changes in circulating sFlt1. The exogenous VEGFA (PH + I/R + VEGFA) exacerbated hepatic damage (especially necrotic cell death), with increased AST and ALT levels, and hepatic dysfunction (evaluated by bilirubin levels), which was greater than that induced by the liver surgery by itself (PH + I/R). Meanwhile, no changes in liver regenerative failure (evaluated by Ki67 and PCNA) were observed after exogenous VEGFA administration, compared with the PH + I/R group.

It should be taken into account that all the drugs were administered before liver surgery, the duration of which was more than 2 h. Consequently, the changes we observed in the different parameters were at least 6 h after administration (2+ h surgery and 4 h reperfusion). These results are in concordance with previous studies in different LT and PH + I/R models, in which the peak of transaminases and regenerative parameters occurred 4 h after reperfusion in the context of 2-h long surgeries. Therefore, the surgical context is the same60,61,81,82,83. It should also be noted that we did indeed observe differential effects and signaling pathways when the different drugs were administered. The transduction of VEGFA signaling within 4 h of reperfusion (or at least 6 h if we consider the time between drug administration and sample collection) is reflected in our current study. As mentioned before, the administration of VEGFA (PH + I/R + VEGFA) induced changes in the parameters reflecting hepatic damage: levels of AST, ALT and bilirubin were higher than those observed in the PH + I/R group. Thus, exogenous VEGFA triggers mechanisms that increase hepatic damage to levels even higher than the surgical procedure by itself. Moreover, our results confirm that the administration of VEGFA in healthy livers using the same surgical procedures (PH under 60 min ischemia) and 4 h of reperfusion, and the same pretreatment times and dose of VEGFA that were used in T2DM livers, does indeed lead to VEGFA signaling being effectively transduced within this time (4 h after reperfusion). Indeed, the increases induced by exogenous VEGFA in different signaling pathways, such as PKC, are associated with a reduction in the deleterious effects of PH + I/R (Supplementary Figure 5). PKC has been reported to be a beneficial modulator in the context of liver damage, decreasing hepatocyte killing by hypoxia84. It has also been reported previously that VEGFA regulates PKC activity in in vitro models85. All of these results together with others reported in the literature4,86 confirm the transduction of VEGFA signaling within 4 h of reperfusion. Thus, VEGFA can trigger signaling pathways within hours or possibly minutes. It should be considered that the times in which the transduction of VEGFA signaling occurs depend on numerous factors such as surgical conditions, the different pathologies, the cell type, and the downstream pathways of VEGFA.

When the role of endogenous VEGFA was evaluated by administering an antagonist of its receptor VEGFR2 (PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2), the effects on hepatic damage (necrosis and apoptosis) were practically of the same order as those for the PH + I/R group. However, an increase in liver regeneration parameters (Ki67 and PCNA) was observed, compared to those of the PH + I/R group. Consequently, it is important to note that VEGFA exhibited differential effects on damage and regeneration in livers in the presence of T2DM undergoing PH + I/R depending on the VEGFA source (exogenous or endogenous). The injurious effects of exogenous VEGFA might be explained by exacerbated hepatic damage (especially necrosis rather than apoptosis) whereas the inhibition of endogenous VEGFA promoted liver regeneration without altering hepatic damage. In our view, the results presented herein are of clinical and scientific interest as they establish the injurious effect of exogenous VEGFA, in contrast to the dogma on the beneficial properties of VEGFA under different surgical conditions63,87,88,89,90,91 and pathologies related to metabolic disorders, such as T2DM4,92,93. Therefore, in the presence of T2DM, to protect livers undergoing PH under vascular occlusion from regenerative failure, we should inhibit endogenous VEGFA action, for instance with an antagonist against its receptor (as in the current study). It is of considerable scientific and clinical interest that if we inhibit the action of endogenous VEGFA in the presence of T2DM, we promote liver regeneration after PH under vascular occlusion.

In accordance with all these observations, it should be considered that by evaluating the expression of Ki67 and PCNA, differences in liver regeneration were observed after 4 h of reperfusion when VEGFA action was inhibited. This reflects the rapid onset of cellular proliferation in response to stimuli in the case of hepatic damage in a pathological liver in the presence of T2DM when subjected to a surgical procedure. Under such conditions, the liver is expected to trigger mechanisms that repair liver damage, including increasing Ki67 and PCNA. Changes in the parameters of liver regeneration have also been observed 4–6 h after reperfusion under conditions of liver surgery4,50,54,57, and in different pathological livers60,82,83,94,95,96. We also need to bear in mind that T2DM might affect cellular proliferation, since it can induce alterations in different metabolic pathways. Therefore, cellular responses including cell proliferation, may be altered due to different factors such as insulin resistance glucose dysregulation, or other physiological changes7,11,12,17,97,98. Moreover, hepatic resection induces more damage in pathological livers4,50,54,57. Thus, a faster cellular proliferative response might be expected, targeted at repairing liver damage. In our view, such results, including early expression of Ki67 and PCNA (in our case, induced by inhibition of VEGFA action), which counteract adverse consequences of surgical procedures, are also of scientific and clinical interest. Early regenerative parameters (Ki67 and PCNA expression 4 h after reperfusion in hepatic resection with T2DM) can serve as a sensitive biomarker to assess initial responses to medical treatments, thereby improving the management of complications and facilitating clinical decision-making and therapeutic adjustments.

Furthermore, Ki67 and PCNA expression are widely used as markers for assessing active cell proliferation and can be observed within the first few hours, depending on cell type, experimental and surgical conditions, and the basal status of the liver (healthy or pathological) or the stimulus applied. Some cells may exhibit a faster and more robust response than others, depending on the damage to be repaired99. Thus, the presence of VEGFA inhibitors, or other stimuli, can expedite cells entering into the active proliferation phase and increase expression of proliferative parameters more rapidly100,101. In addition, the exact time it takes for regenerative expression to become detectable can vary based on several factors: different cell types have varying rates of proliferation and responses to stimuli. For example, highly proliferative cells such as cancer cells or endothelial cells might show faster expression of proliferative markers than quiescent cells like neurons102,103. The concentration and potency of the stimulus also play crucial roles in accelerating the onset of expression of regenerative mechanisms13,21 while rapid changes in the expression of regenerative parameters following drug treatment can indicate therapeutic effects or resistance mechanisms4,13,21.

Moreover, the following points should also be considered. Firstly, in clinical practice, liver samples are preferably collected during surgery, before closing the patient (2–4 h after reperfusion), rather than after longer reperfusion times. Secondly, after 4 h of reperfusion, peak transaminase values are observed4,50,54,57,104,105; it is important to establish whether at this time the proliferating markers which indicate that tissue damage is being repaired are high, as well as the effects that the different drugs used have on hepatic damage and the regenerative process. Thirdly, collection during surgery avoids the need for additional invasive procedures and, consequently, reduces the risk of important infections and other critical postoperative complications (cardiac and respiratory complications due to additional anesthesia, sepsis, abscess generation with associated intestinal obstructions, increased bleeding, different morbidities, and mortality risk)106,107, as well as recovery times. It should be borne in mind that here and in the studies cited, hepatic resection was performed in the presence of T2DM and with pathological livers that tolerate hepatic resection poorly.

Meanwhile, the protection against regenerative failure resulting from the inhibition of the action of endogenous VEGFA using an antagonist against VEGFR2 (PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2) was not associated with changes in the levels of ID1/Wnt2, indicating a minor role of this signaling pathway in the mechanism of action of endogenous VEGFA for PH under vascular occlusion in the presence of T2DM. However, PI3K/AKT might be responsible for the benefits resulting from the inhibition of the action of endogenous VEGFA. The relevance of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway for liver regeneration processes has been extensively reported in liver surgery64,108.

Our results indicating that VEGFA inhibition using an antagonist against VEGFR2 was related to an increase in liver regeneration are in contrast with different studies indicating that VEGFA is crucially associated with the process of conversion of biliary epithelial cells (BEC) to hepatocytes, which also aids regeneration in acute and chronic liver injury. The effect of drugs or factors such as VEGFA on liver regeneration may vary according to the animal species selected, the liver pathologies, or the surgical conditions, among many other factors. Accordingly, different effects of VEGFA on liver regeneration can be expected if our results are compared with other interesting results reported in the literature19,109. Indeed, the studies carried out by Cai et al. 19 and Rizvi et al. 109 were performed in different animal models (mice and zebrafish, vs rats in our case). Moreover, those studies were performed in the context of pathologies and liver damage that were totally different from those we investigated. While our study focused on liver subjected to PH under I/R in T2DM rats, those other studies used models of liver damage after hepatocyte ablation in zebrafish, and a choline-deficient diet or acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury in mice. Furthermore, apart from the differences in the type of liver damage induced in the models used (zebrafish and rat), the studies performed on zebrafish were conducted in genetically modified organisms whereas in the current study, the rats were not genetically modified. In addition, zebrafish present differential histological characteristics that are distinguishable from those in mammals. Zebrafish present portal veins, hepatic arteries, and large biliary ducts differently distributed from mammalian versions and, moreover, the organizational structure of the hepatocytes is different: zebrafish hepatocytes are arranged as tubules that enclose small bile ducts, rather than as mammalian bilayered hepatocyte plates110. Finally, whereas rats share 90% of their genome with humans111, zebrafish share only 71.4% of their genes with our specie112. Given all of these observations, rats present more similarities regarding liver architecture, as well as cellular structure and composition, with humans than zebrafish, making them a closer model of clinical scenarios, at least in PH under vascular occlusion.

To understand the effects of VEGFA, we need to consider that the exogenous effects of VEGFA are very different from those of endogenous VEGFA in pathological livers subjected to PH under vascular occlusion in the presence of T2DM. This should not come as a surprise because numerous studies of liver surgery indicate that the effects and various signaling pathways related to different mediators or factors (including NO, among others) can be very different when the mediator is regulated exogenously or endogenously59,60,113. It is also possible that exogenous VEGFA could affect pathways other than those triggered by endogenous VEGFA (that is to say, mechanisms other than the PI3K/AKT pathway). In line with this, when we administered VEGFA, we observed an increase in hepatic damage without any changes in either regeneration or PI3K/AKT. However, if we inhibited the action of endogenous VEGFA, the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway was upregulated, and this resulted in improvements in liver regeneration. These results indicate that the effects of the administration of exogenous VEGFA are independent of the changes in PI3K/AKT, whereas the improvements in liver regeneration induced by the inhibition of endogenous VEGFA are exerted via increased PI3K/AKT expression. This explains why we observed specific effects on the degree of liver damage and regenerative failure depending on the VEGFA source (exogenous vs endogenous). The injurious effects of exogenous VEGFA might be explained by exacerbated hepatic damage (especially necrosis, rather than apoptosis) without changes in PI3K/AKT levels. In contrast, endogenous VEGFA mainly improved the regenerative process via PI3K/AKT upregulation.

In the context of previous studies indicating a relationship between VEGFA and VEGFB6,35,36,39, we wanted to test whether VEGFA induced changes in the levels or role of VEGFB in PH under I/R in the presence of T2DM. This turned out not to be the case: pharmacological modulation of VEGFA (PH + I/R + VEGFA and PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2) did not alter the protein levels of VEGFB in the liver. Different results (injurious or beneficial actions) have been reported in studies of VEGFB in T2DM without liver surgery46,47. Our present work is therefore the first study to report that the pharmacological modulation of VEGFA (PH + I/R + VEGFA and PH + I/R+anti-VEGFR2) does not affect the hepatic levels of VEGFB, compared with PH + I/R. In addition, herein we demonstrate, for the first time, that administration of exogenous VEGFB (PH + I/R + VEGFB) negatively affects hepatic damage. In addition, no improvements in the parameters reflecting liver regeneration were observed in relation to PH + I/R. Thus, in our view, the administration of exogenous VEGFB should not be recommended as a strategy in PH + I/R with T2DM.

We observed that the injurious effects of VEGFA and VEGFB during PH + I/R in the presence of T2DM trigger mechanisms that circumvent increases in the protein levels of both VEGFA and VEGFB in the liver and thereby counteract damage and regenerative failure. This hypothesis might be seen as reinforced by the results mentioned below.

We observed that the reduction in the protein levels of VEGFA in the liver of the PH + I/R group compared with the Sham group was not associated with a reduction in the hepatic synthesis of VEGFA. Since intestine and adipose tissue might contribute to regulating or, in contrast, inducing dysfunctions in the hepatic levels of different mediators49,50, we evaluated the potential contribution of intestine and adipose tissue to maintaining low levels of VEGFA in the liver. We observed no changes in the protein levels of VEGFA in the intestine, between Sham and PH + I/R, while we found an increase in adipose tissue VEGFA protein levels in the PH + I/R group, compared with the Sham group. Thus, we believe that VEGFA could be taken up from circulation by adipose tissue, thereby maintaining VEGFA protein levels low in the liver and avoiding its injurious effects. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the levels of sFlt1 (which would sequestrate VEGFA to maintain hepatic levels of VEGFA low) were similar for the Sham and PH + I/R groups.

Meanwhile, we observed increased VEGFB mRNA levels in the liver of the PH + I/R group, compared with the Sham group. However, the VEGFB protein levels were similar in the Sham and PH + I/R groups. The literature describes in detail that mRNA levels are not necessarily proportional to protein concentration114,115. Therefore, although the mRNA increased, we hypothesize that in PH + I/R with T2DM, the VEGFB protein concentrations are blunted at Sham levels, which avoids the injurious effects of hepatic VEGFB in terms of damage and regenerative failure. In line with this, a reduction of both VEGFB mRNA and protein levels in the intestine was observed in the PH + I/R group, compared with the results of the Sham group, probably resulting in hepatic levels of VEGFB remaining low, thus avoiding its injurious effects. Obviously, intensive research (which was not part of the present study) will be necessary to completely determine the mechanisms by which the protein levels of both VEGFA and VEGFB are reduced or maintained at Sham levels following PH under I/R in the presence of T2DM. Nevertheless, the mechanisms that maintain hepatic levels of VEGFA and VEGFB low after PH + I/R with T2DM seem to be specific, depending on the type of VEGF (VEGFA or VEGFB).

In conclusion, our experimental results indicate an increase in hepatic damage and liver regeneration failure under PH + I/R conditions in the presence of T2DM (Fig. 10). This was associated with reduced protein levels of liver VEGFA, as well as the injurious effects of exogenous and endogenous VEGFA under these surgical conditions. Specific effects on liver damage and regenerative failure were evidenced depending on the VEGFA source (exogenous vs endogenous VEGFA). The injurious effects of exogenous VEGFA might be explained by exacerbated hepatic damage (especially necrosis rather than apoptosis), whereas endogenous VEGFA improved liver regeneration through PI3K/AKT upregulation. VEGFA did not induce changes in the protein levels of VEGFB in the liver. The administration of exogenous VEGFB negatively affected hepatic damage and resulted in liver regenerative failure similar to that of PH + I/R. Extrahepatic tissues, such as intestine and adipose tissue, as well as a potential disruption in the steps required to induce the synthesis of VEGF proteins, might be occurring under PH + I/R conditions and in the presence of T2DM, which maintain liver levels of VEGFA and VEGFB low and, consequently, avoid their exacerbating effects on damage and regenerative failure. Thus, we propose the inhibition of endogenous VEGFA (but not the exogenous administration of VEGF) as a suitable strategy to promote liver regeneration in PH under vascular occlusion and in the presence of T2DM. Moreover, further research should be carried out to elucidate whether the potential effects of VEGFs demonstrated here in PH + I/R with T2DM extrapolate to LT, as some aspects, including the warm I/R period, are shared between the surgeries (PH + I/R and LT). The potential results derived from such studies would improve the quality of liver grafts from deceased donors implanted in recipients with T2DM (a common pathology in patients on waiting lists for LT).

T2DM increases damage and decreases liver regeneration, leading to liver regeneration failure. VEGFA has a detrimental effect in rats with T2DM subjected to PH + I/R, both in its exogenous and endogenous forms, although via different mechanisms. Exogenous VEGFA increases liver damage and decreases liver function, while inhibition of endogenous VEGFA improves liver regeneration. Exogenous VEGFB administration also increases liver damage. Moreover, the body activates specific mechanisms to reduce VEGFA and VEGFB in the liver, related to adipose and intestinal tissue, respectively.

Responses