Gut microbiota and dynamics of ammonia metabolism in liver disease

Introduction

The gut microbiome dynamically interacts with the human physiology to maintain the integrity of the intestinal microecosystem. The metabolism of ammonia is influenced by both the host’s intestinal metabolic machinery and the gut microbial community1. The liver primarily catabolizes ammonia and in conjunction with other organs plays a crucial role in controlling its level in the bloodstream. When ammonia metabolism (both production and clearance) in the intestine, liver, or other organs is disturbed, for example in liver diseases, its levels in the blood are elevated (known as hyperammonemia) and this can have deleterious effects, particularly leading to complications such as increased hospitalization and hepatic encephalopathy (HE)2. While it has been widely accepted that an imbalance in gut bacteria plays a significant role in the development and advancement of liver disease, the connections between the gut microbiome and the metabolism of ammonia remain understudied. Here, we highlight the significance of gut microbiota in the production and consumption of ammonia and make an effort to link changes in gut microbial populations to ammonia metabolism and levels in liver diseases. In this review, we would be discussing ammonia metabolism in chronic liver disease and cirrhosis and not ACLF or ALF.

Ammonia metabolism in health and disease

Synthesis of ammonia in health

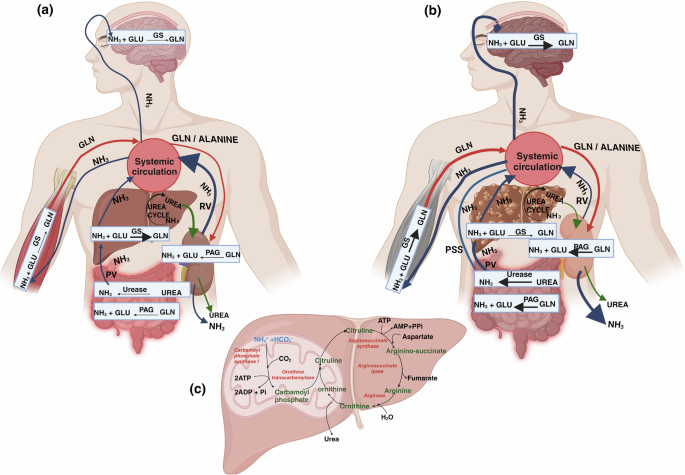

Ammonia is an important metabolite that maintains cellular pH. In nature, ammonia exists in gaseous and ionic form as ammonium ion (NH4+), which are in equilibrium with each other. Recently, it has been shown that an NH4+ uses transporters to transverse the cell membrane, where it first dissociates into ammonia and hydrogen ion (a proton), which then pass through the cell membrane and then finally both again combine into NH4+ inside the cell3. The blood levels of ammonia must remain very low because even slightly elevated concentrations are toxic to the central nervous system4. In healthy humans, blood ammonia levels are maintained in the range of 10–40 μM5. Most of the ammonia in circulation originates from the gastrointestinal tract from the catabolism of dietary proteins and amino acids. Among all amino acids, glutamate and glutamine are most prominent players of nitrogen and ammonia metabolism6. In the intestine, ammonia is primarily produced through two processes. Firstly, it is formed when glutamine is deaminated by phosphate activated glutaminase (PAG) in the enterocytes lining the mucosal layer of small intestine and colon. Secondly, it is generated from the conversion of dietary urea (protein rich foods) or hepatic urea (15–30%) by the gut microbial urease enzyme, which is abundant in the colon7 (Fig. 1a). In healthy individuals, ~80% of intestinal PAG is located in the small intestine, whereas the remaining 20% is found in the large intestine8. During the post-absorptive state, as seen in dogs, approximately 50% of intestinal ammonia originates from metabolism of glutamine in small intestine, 21% comes from breakdown of urea in the large intestine while 5% comes from glutamine metabolism in large intestine9. The kidneys also play a role in ammonia production by means of PAG majorly in renal epithelial cells in the proximal tubule. During the post-absorptive stage, glutamine coming from the liver serves as the primary substrate for renal production of ammonia through the action of PAG10. Along with ammonia, kidneys also produce equimolar bicarbonate generation (two NH4+ and two bicarbonate molecules). Thus, ammonia metabolism in the kidneys is critical to maintain acid base homeostasis11.

a Interorgan ammonia metabolism in Health: NH3 produced in the gut and kidneys through the activity of PAG and also from gut microbial urease enzyme travels to liver via PV for detoxification by urea cycle and GS. Some detoxification of systemic blood NH3 takes place in brain and muscles by GS. Muscles supply Gln to all organs like gut, kidney, and liver through blood. Gln is again used to make NH3 by PAG in kidneys and gut. In kidneys, 30% NH3 is excreted in urine and rest 70% goes back to the systemic circulation via RV. b Interorgan ammonia metabolism in Liver disease: Increased NH3 production takes place in the dysbiotic gut through increased activity of both PAG and urease enzymes. NH3 travels to diseased liver via PV which has reduced NH3 detoxification by both urea cycle and GS. Increased Gut NH3 also reaches systemic circulation directly via PSS. Increased systemic NH3 crosses blood brain barrier, GS activity in brain is increased leading to high Gln levels causing neuro-complications. Muscles receive high NH3 and their GS activity increases to convert NH3 into Gln. More Gln from muscle enters systemic circulation which may again travels to kidneys, further increasing NH3 production by PAG. During liver disease, kidneys excrete 70% NH3 in urine and only 30% goes back to systemic circulation via RV. Different color of the arrows shows, Dark Blue: NH3, Red: Gln, Green: urea. Thicker arrows represent increased production. NH3 (ammonia); GLU (glutamate); GLN (glutamine); PAG (phosphate activated glutaminase); GS (glutamine synthetase); PV: Portal Vein; RV: Renal Vein; PSS: Porto-systemic shunts. c Steps of Urea cycle: Conversion of ammonia to urea through a series of biochemical reactions taking place in the liver with the help of mitochondrial and cytosolic enzymes. All the enzymes are indicated in red color.

Synthesis of ammonia in liver disease

Arterial ammonia levels in patients with liver disease range from 40–60 μM in cirrhosis. Changes in arterial ammonia levels are better indicators of liver disease as they are representative of changes in urea cycle enzymes in liver as compared to venous ammonia levels, which are less accurate because of peripheral uptake of ammonia into muscle and brain tissue12. Studies have shown that elevated intestinal PAG activity plays a significant role in enhanced systemic blood ammonia or hyperammonemia during liver disease (Fig. 1b). Preclinical investigations have reported that duodenal PAG activity in mucosal biopsies of the small intestine increase by almost four times in cirrhotic patients compared to healthy individuals8. Studies have shown that hyperammonemia is primarily caused by preexisting intra- and/or extrahepatic portacaval shunts (that directly connect portal to systemic blood) in rats with cirrhosis. Several studies have proven that portal-systemic shunting is the major cause of elevated ammonia levels in the systemic circulation. This has also been shown in stable individuals with cirrhosis and TIPS (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt). In comparison to controls, both portal and arterial ammonia increases substantially after portacaval shunting13,14. The hepatic extraction efficiency of ammonia from the portal vein is about 93%in health15. Thus, little, if any, ammonia enters the systemic circulation from the portal vein under normal conditions, and the liver maintains the level of circulating ammonia at relatively low levels. Ammonia extraction is reduced in the presence of portosystemic shunting16. This is attributed to a predominance of pathobionts within the gut microbiome that produces more ammonia irrespective of the degree of portosystemic shunting17. The microbiome also contributes towards increased synthesis of intestinal ammonia through the action of the bacterial enzymes18. Studies have demonstrated that in patients with advanced cirrhosis and upper gastrointestinal bleeding, kidneys have a six-fold increase in ammonia production due to increased alanine uptake19. However, it has also been shown in experimental and clinical studies that kidneys remove more ammonia from the body than its production following hyperammonemia induced by portacaval shunting14.

Ammonia removal in health

Liver

Ammonia is efficiently detoxified in the liver through either the conversion into urea via the urea cycle enzymes or the conversion into glutamine through the activity of glutamine synthetase (GS) (Fig. 1a, c). The enzymes responsible for the urea cycle are mainly found in periportal hepatocytes, whereas GS is significantly abundant in perivenous hepatocytes20. The initial stage of the urea cycle is controlled by the enzyme carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I (CPS I), which acts as a rate-limiting enzyme. In the first stage, carbamoyl phosphate and ornithine react together, resulting in the production of citrulline which in further stages with the help of other enzymes, produces urea21 (Fig. 1c). Urea is passively transported across the biological membranes by diffusion and with the help of urea transporters, it is ultimately removed by the kidneys in the urine22. The perivenous hepatocytes convert ammonia to glutamine by GS, thus providing an alternate method for scavenging ammonia20. Hepatic glutamine metabolism, together with urea synthesis, has a vital role in maintaining the detoxification of ammonia in the body23.

Muscles

In addition to the liver, GS activity is also found in the muscles, but it is lower compared to the liver during health. By employing genetic methods to completely eliminate GS from muscle, it has been demonstrated that GS has a minimal role in muscle during normal fed conditions, and only becomes significant during times of stress, such as starvation or hyperammonemia24.

Brain

The brain exhibits GS activity majorly in astrocytes and some in the neurons, rendering it an essential organ for detoxification and utilization of ammonia in the maintenance of a healthy state25. Astrocyte GS utilizes ammonia in order to produce glutamine, which is subsequently delivered to neurons for deamination to produce crucial neurotransmitters glutamate and GABA26.

Kidneys

The kidneys closely regulate the elimination of urinary ammonia by many mechanisms, including tubular urine flow, apical/basolateral ion exchangers (such as Na + –K + –NH4 + –ATPase), acid-base balance, and ammonia counter-current system27. The regulation of ammonia transport by renal epithelial cells determines the amount of ammonia that is excreted in urine or returned to the systemic circulation. Under basal conditions, 30% of the ammonia that is produced in kidneys is excreted in urine and 70% is added to the systemic circulation via renal veins10.

Ammonia removal in disease

Liver

Chronic liver disease causes a decreased clearance of ammonia in liver. A decline in the expression and activity of urea cycle enzymes leads to hyperammonemia28 (Fig. 1c). In cirrhosis, the loss of hepatocytes results in a significant reduction in the liver’s capacity to detoxify ammonia through the urea cycle or GS activity29 (Fig. 1b). However, generally there is enough capacity to remove ammonia from the body until the emergence of advanced chronic liver disease. Many patients with stable cirrhosis show normal systemic ammonia levels, indicating that the liver is still capable of efficiently removing majority of ammonia from the portal vein and hepatic artery. This is also evident by the fact that a large increase in protein intake in patients with cirrhosis enhances functional hepatic nitrogen clearance and urea synthesis30. During advanced liver disease, reduced hepatic clearance, and presence of portal-systemic shunting, are important causes of hyperammonemia9,29. Using a 90 min constant infusion of ammonia to achieve plasma steady-state, Eriksen et al. clearly demonstrated that in patients with cirrhosis, ammonia clearance was ∼20% lower and ammonia production nearly threefold higher than in healthy persons, indicating relevance of both ammonia clearance and production in governing plasma ammonia levels29.

Kidneys

During liver cirrhosis and portocaval shunting, kidneys respond to early hyperammonemia by enhancing ammonia excretion in the urine (70%) and decreasing its secretion into the renal vein (30%)14. The improvement of renal ammonia excretion following TIPS and the decrease in renal ammonia release into circulation in patients with cirrhosis provide supporting evidence for this19. Changes in urinary ammonia excretion can result from changes in renal epithelial cell ammonia transport that determines the proportion that is excreted in the urine versus that delivered to systemic circulation10.

Muscles

Due to the presence of GS activity, muscle is considered as a good buffer system to dispose of excess circulating ammonia during liver disease. GS activity in muscles is known to increase during hepatic insufficiency and portosystemic shunting31. Cirrhotic patients with a normal muscle mass may experience a less severe form of hyperammonemia while those having significant muscular atrophy are more susceptible to developing hyperammonemia13. The relationship between hyperammonemia and muscle mass is complex. Hyperammonemia is known to have a direct negative effect on muscle turnover by causing an increased activation of myostatin (an inhibitor of muscle growth), mitochondrial dysfunction with decreased ATP content, modifications of contractile proteins, and impaired ribosomal function32. Sarcopenia (reduced muscle mass and strength), that is present between 30% and 70% of cirrhotic patients and low myostatin levels have been independently associated with the development of HE33. Also, due to excessive protein catabolism in a sarcopenic muscle, glutamine synthesis by GS may be decreased and hence cirrhotic patients with sarcopenia will have a reduced GS activity and a higher risk of developing HE34,35. In addition, it is important to note that the process of skeletal muscle ammonia uptake and glutamine release does not always result in overall detoxification of ammonia in the body. This is because the glutamine produced by the muscles can be absorbed by the splanchnic area or kidneys and converted back into ammonia, which is then released into the bloodstream36. Maintaining an optimum muscle mass by light exercise and increased caloric intake have been shown to be beneficial in patients with compensated cirrhosis in a few studies but long-term clinical effects in patients with hyperammonemia need to be clarified further36.

Brain

Enhanced ammonia detoxification via the conversion of glutamate to glutamine by brain GS results in elevated levels of glutamine, causing osmotic stress and subsequent cell swelling. Brain glutamine levels correlate with the grade of HE in patients with cirrhosis37. The underlying pathophysiology of HE in cirrhosis is multifactorial, involving accumulation of ammonia and manganese in brain, systemic and central inflammation, activation of the GABAergic neurotransmitter system, etc. Astroglial and microglial cells are the major cells affected during HE in cirrhosis patients38.

Gut microbiome in liver disease

Microbial species have been identified in several parts of the gut, such as the mucosa-associated microbiota (intestinal biopsies) and the luminal or stool microbiota, using 16S rRNA gene sequencing39,40. The mucosal microbiota, located within the mucus layer that adheres to the mucosa, differs from and remains more consistent throughout time compared to the luminal counterpart. In contrast to luminal or stool microbiota, the mucosal microbiota engages more closely with the host. Therefore, changes in the stool microbiota may not provide an adequate representation of the complex interactions that take place immediately at the surface of the gut mucosa. Nevertheless, because of the challenge of acquiring mucosal microbiota, most of the studies have opted for stool sampling as a means of screening microbiota40. Gut and stool microbiota have been linked to the progression of almost all liver diseases, regardless of their etiology41.

Gut microbiota and ammonia metabolism

The gut microbiota is intricately linked to the processes of nitrogen and ammonia metabolism, and any modifications in the microbiome can cause major disturbances that ultimately impact the entire system. The small intestinal lumen harbors a substantial number of live bacteria, but this number is even higher in the large intestine. Small intestinal microbiota plays an important role in metabolism of nitrogen and ammonia. Dietary and endogenous proteins are a potential source of amino acids for the microbiota. These amino acids are utilized by the bacteria for protein synthesis, production of metabolic energy, and recycling of reduced co-factors42. Our understanding of ammonia metabolism by the microbiota in the small intestine remains limited in comparison to the large intestine or colon. Hence, in this review, we have restricted our discussion to the large intestine only. In healthy individuals, the concentration of ammonia in the lumen of large intestine is typically low due to the presence of low pH and high amounts of carbohydrates which prevent the synthesis of ammonia40.

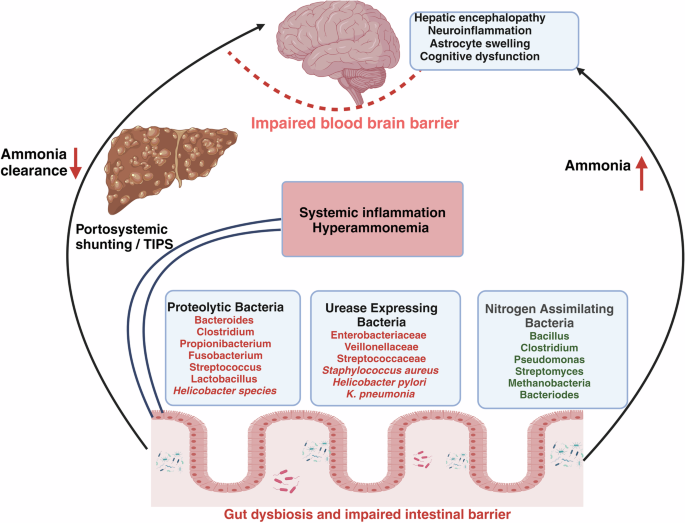

Ammonia production by microbial urease activity

Several gut microbial species in the colon are involved in the production of ammonia, either through the conversion of urea by bacterial urease or through proteolysis activities. Urease is an enzymatic protein synthesized by bacteria that facilitates the conversion of urea into carbamate and ammonia. Mammals do not possess any identified urease gene, therefore, the process of urea breakdown in the colon, facilitated by urease, is dependent only on the gut microbiota43,44. Urea transporters are found in the colonic mucosa and are involved in delivering dietary or systemic urea from the bloodstream to the intestinal lumen45. The majority of the bacteria that produce urease are mainly Gram-negative facultatively anaerobic bacteria belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae and Veillonellaceae families. Klebsiella pneumoniae, a member of the Enterobacteriaceae family, has demonstrated significant urease activity in the in vitro investigations. In addition, it is worth noting that anaerobic gram-positive bacteria, such as Streptococcaceae, possess significant urease activity46. More than 90% of clinical strains of methicillin-resistant gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus also have the ability to break down urea by hydrolysis. The significance of urease in facilitating bacterial survival in hostile microenvironments within the host’s body is particularly evident in the instance of Helicobacter pylori (H pylori), a pathogen accountable for gastritis and peptic ulcers, which maintains its activity at the pH of stomach. H. pyrloi possesses the ability to produce ammonia as a result of its urease activity47. They demonstrate a markedly higher level of urease activity as compared to numerous other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family48. Studies have shown that H. pylori increases the generation of ammonia in laboratory conditions and in rat models of cirrhosis. While there has been extensive research on urease activity in H. pylori, there is limited evidence on urease activities in other bacterial species found in the large intestine49.

The existence of commensal bacteria possessing urease activity, which generates endogenous ammonia, implies a crucial role of ammonia generation in physiological processes conducted an excellent study that reported an advantageous function of naturally occurring ammonia synthesis by gut urease bacteria (Figure 2). A strain of urease-expressing bacteria, called Streptococcus thermophilus, was found to reverse depression-like behaviors in mice. When the production of ammonia in the gut was blocked by inhibiting the activity of urease-producing bacteria, it increased vulnerability to stress49, indicating the significance of urease bacteria in maintaining ammonia levels for physiological functions.

Impaired intestinal barriers lead to gut dysbiosis and changes in gut microbial composition. Three major types of bacterial species contribute to the process of ammonia metabolism. Nitrogen-assimilating bacteria utilize ammonia for their metabolism. Some bacteria contribute to ammonia production by proteolytic activities in the colon and urease-expressing bacteria contribute to synthesis of ammonia from urea. Urease-expressing bacteria may increase during liver disease, leading to higher ammonia production in the gut and also in the systemic blood via natural portosystemic shunts or after TIPS (Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt). A reduced ammonia clearance in the liver further increases blood ammonia. Increased systemic ammonia subsequently crosses the blood-brain barrier, resulting in complications including hepatic encephalopathy, neuroinflammation, and brain edema.

Ammonia production by microbial proteolytic activity

In addition to urease, a variety of bacterial species in the colon produce ammonia by proteolytic activities. The primary organisms responsible for the breakdown of proteins in the large intestine are the Bacteroides, Clostridium, Propionibacterium, Fusobacterium, Streptococcus, and Lactobacillus genera. Bacteroides species, including Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides fragilis, release proteases in the intestines50 (Fig. 2). Vince et al. isolated specific proteolytic bacteria from healthy subjects and tested their ability to produce ammonia. The study found that the bacteria responsible for ammonia production were primarily gram-negative anaerobic and aerobic rods, such as Clostridia, Bacillus spp, some Helicobacter sp., Mycobacterium TB, Mycobacterium bovis, and Vibrio parahaemolytic. Research has shown that microbial proteases play a role in disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)51, however, their role in cirrhosis remains completely unexplored. In cirrhosis, a study by Kang et al. observed that in the large intestine, PAG activity was decreased in germ-free cirrhotic mice as compared to conventional cirrhotic mice indicating that PAG activity is contributed by both host and gut microbiota. In the large intestine and cecal lining of conventional cirrhotic mice, they also reported an increased abundance of Staphylococcaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Lactobacillaceae and lower abundance of indigenous families like Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Clostridiales XIV and Bifidobacteriaceae. Although the proteolytic or urease activities of these bacteria were not studied, the relative abundance of these bacterial families was positively correlated with increased systemic ammonia and neuroinflammation52.

Gut microbiota and ammonia production in cirrhosis and HE

Pyrosequencing of the 16S rRNA V3 region has shown that the composition of the stool microbiota in the cirrhosis patients varies in terms of both phyla and families. The families Enterobacteriaceae, Veillonellaceae (Gram-negative facultative anaerobic bacteria), and Streptococcaceae (anaerobic gram-positive bacteria) are commonly found in patients with cirrhosis at the family level. A positive correlation has been identified between the Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score and Streptococcaceae in patients with cirrhosis53. Rai et al. revealed a positive correlation between the severity of cirrhosis as measured by the Model for End Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, and the presence of the harmful gut bacterial phylum, Enterobacteriaceae. Conversely, a negative correlation between the severity of cirrhosis and the presence of Ruminococcacea in the gut was seen54. In cases of more severe liver diseases such as acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), it has been observed that the presence of harmful bacterial families, specifically Proteobacteria, Enterococcaceae, and Streptococcaceae, is associated with greater mortality and poor outcomes55. Although no quantitative correlations have been done, yet the presence of increased abundance of gut bacterial families such as Veillonellaceae and Streptococcaceae has been suggested to correlate with increased production of gut ammonia in cirrhosis53. An increase in ammonia production in the large intestine during cirrhosis can be attributed to a decrease in the presence of beneficial commensal bacteria and the generation of short-chain fatty acids and organic acids. These substances increase the pH of the large intestine, which in turn enhances bacterial metabolism and leads to an increase in ammonia production. Alterations in the microbiota during cirrhosis can also lead to modifications in the process of bacterial nitrogen assimilation. A majority of gut bacteria have the ability to manufacture glutamate dehydrogenase and utilize ammonium in their metabolic pathways, allowing many gut symbionts to ingest ammonium56. This is important for detoxification since high levels of ammonium can be detrimental to both microbiota and host. Some of the bacterial taxas which are known to be utilizing ammonia for their metabolic activities are Bacillus, Clostridium, Pseudomonas, Streptomyces, Bacteroides, Methanobacteria57,58. However, as of date, there is limited knowledge of the specific relationship between the type and quantity of gut bacteria and the generation or utilization of intestinal ammonia in cirrhosis (Fig. 2).

Given the prominent role of ammonia in the development of HE, several studies have investigated gut microbial changes in patients with HE. HE has been classified into two categories based on the severity of symptoms: overt HE (OHE), which is fully symptomatic, and a less symptomatic state known as minimal HE (MHE)54. The main pathophysiological mechanism of OHE and MHE is hyperammonemia leading to astrocyte dysfunction and deficits in some cognitive areas that can only be measured by neuropsychometric testing. Psychometric and behavioral changes are present with lesser or no symptoms in MHE but hyperammonemia exists in both conditions59. The gut microbiome of cirrhotic individuals with MHE has a significant increase in Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus spp. compared to patients without MHE60. Zhang et al. identified distinct changes in patients with cirrhosis and MHE, including a higher abundance of Streptococcus salivarius compared to those without MHE. Remarkably, a direct association between the prevalence of Streptococcus salivarius and the accumulation of ammonia in cirrhotic individuals with MHE was also seen61. Another study demonstrated the presence of urea catabolite genes in Streptococcus salivarius, which were associated with increased activity of the urease enzyme. Therefore, the connection between Streptococcus salivarius and hyperammonemia in individuals with minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE) could be attributed to the significant urease activity exhibited by these bacteria59. In another study, it was discovered that the presence of Alcaligeneceae (Gram-negative, aerobes) and Porphyromonadaceae (gram-negative anaerobes) in stool was positively correlated with cognitive impairment in patients with cirrhosis. Importantly, the link between HE and cognitive impairment was attributed to the capacity of Alcaligenaceae to produce ammonia through the breakdown of urea47.

Gut microbiota-targeted ammonia-lowering therapies

Although not many studies have evaluated the contribution of gut microbiota to ammonia production in HE and cirrhosis pathogenesis, interestingly, most of the successful ammonia-lowering therapies in HE are either based on changing the pH of the gut or modulating the gut microbiota. Since hyperammonemia is associated with HE in patients with cirrhosis, here we discuss these therapies in context of HE.

Lactulose

Lactulose is a synthetic sugar that is not broken down by the body until it reaches the colon. In the colon, it gets converted by bacteria into acetic acid and lactic acid. These carboxylic acids lower the pH inside the colon, inhibit the growth and metabolism of urease bacteria, thus reducing ammonia production62. Lactulose also reduces ammonia and other nitrogenous substances from the colon by its cathartic action (which is probably caused by the osmotic effect of the organic acid metabolites of lactulose solution) that expels the trapped ammonium ions63. Lactulose also results in dose-dependent acceleration of the colonic transit time64. Lactulose behaves as a prebiotic and modifies the composition of the intestinal microbiota through an increase in beneficial bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus) and a decrease in potentially harmful bacteria (e.g., Enterobacteria) thereby contributing to healthier intestinal microbiota in patients with cirrhosis65. It would be worthwhile to study the type of gut bacteria being modulated by lactulose treatment and their relation with intestinal ammonia metabolism.

Probiotics

Probiotic therapy entails oral administration of live microorganisms, either monocultures or mixed cultures, with the aim of enhancing beneficial properties of the intestinal microflora62. Several studies have provided evidence that native and engineered probiotics profoundly affect many aspects of intestinal nitrogen metabolism (production or utilization) that reduce the production of ammonia in the gut and hence hyperammonemia. In order to reduce the amount of intestinal ammonia production, Kurtz et al. modified the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 to generate a new strain called SYNB1020 (S-ARG) by upregulating arginine biosynthesis by removing a negative regulator of l-arginine biosynthesis and adding a feedback-resistant enzyme involved in l-arginine biosynthesis. When ingested, this novel variant had the capability to convert ammonia (NH3) into l-arginine. The SYNB1020 in vitro system demonstrated enhanced l-arginine synthesis from ammonia. SYNB1020 illustrated efficacy in reducing systemic hyperammonemia, enhancing survival in ornithine transcarbamylase-deficient mice, and reducing hyperammonemia in thioacetamide-induced liver injury mouse models66. SYNB1020 was safe but could not lower blood ammonia in patients with cirrhosis in a phase 1b/2a trial. In another study by Sanchez et al., the efficacy of genetically engineered E.coli Nissle strains (S-ARG and S-ARG + BUT) was studied on HE. S-ARG + BUT strain along with converting ammonia to arginine, also synthesized butyrate, effectively attenuated hyperammonemia and prevented memory impairment in bile duct ligated rats67. Another study showed that genetically engineered Lactobacillus plantarum strain exhibited exceptional efficacy in converting ammonia to alanine (NH3 hyperconsuming strain) and had significant effects on reducing levels of ammonia in the blood and feces68.

Antibiotics

Oral antibiotics have been commonly used to specifically target pathogenic bacteria in the colon. Neomycin and vancomycin are antibiotics that have been proven to reduce blood ammonia levels in patients suffering from end-stage liver disease7. Neomycin is known to reduce the endogenous production of ammonia and is used for treatment of acute or acute on chronic HE69. Vancomycin has been shown to reduce blood ammonia and also the severity of HE in patients with cirrhosis70. Another antibiotic, rifaximin that is poorly absorbed in the blood and primarily targets gut bacteria, reduces the formation of ammonia in HE71. A randomized, double-blind research showed that the antibiotic rifaximin effectively attenuates HE by reducing arterial blood ammonia, improving in asterixis in patients with chronic liver disease72. Prophylactic administration of rifaximin has shown to improve hyperammonemia and prevent neurophysiological functions in patients with cirrhosis by modulation of metabolic activity of gut bacteria73.

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)

FMT involves the transfer of stool from a donor who has a healthy gut microbiota to a patient who has an imbalanced gut microbiota, with the goal to restore healthy microbiome. A healthy donor is considered the one with no active infections and antibiotics usage within 3 months of enrollment, obesity, diabetes, chronic alcohol intake, IBD, CKD, or any other malignancy74. The administration of FMT led to a decrease in hospitalizations and improved cognitive skills in patients with cirrhosis who experienced repeated episodes of HE75. In patients with advanced cirrhosis, FMT decreased microbial-associated ammonia production and augmented ammonia utilization via anaerobic metabolism of L-aspartate to Hippurate (glycine conjugate of benzoic acid) providing concrete evidence of gut microbiome’s contribution towards altered ammonia metabolism in cirrhosis. Hippurate is a marker of gut diversity, associated with microbial degradation of certain dietary components, and is known to facilitate the disposal of ammonia by urinary excretion76.

Engineered microbiota and urease inhibitors

Administration of modified Schaedler flora (ASF), that consisted of a specific assemblage of eight bacteria with decreased abundance of bacteria containing urease gene resulted in a gradual decrease in ammonia production and fecal urease activity. ASF transplantation was also linked to lower morbidity and death in a mouse model of acute and chronic liver injury77. Urease inhibitors have emerged as an important strategy for reducing ammonia by targeting the synthesis of ammonia by urease bacteria. Acetohydroxamic acid (AHA) is a well-researched compound that inhibits the enzyme urease. It has been suggested as a therapy for chronic urinary infections caused by the breakdown of urea78. Apart from AHA, other potent urease inhibitors, such as octanohydroxamic acid (OHA) and nicotinohydroxamic acid, have been studied as potential therapies for HE. In a recent study, 2-octynohydroxamic acid, a urease inhibitor exhibited minimal cytotoxic and carcinogenic effects at micromolar concentrations and also decreased ammonia levels in mouse models of both acute and chronic liver disease79. However, more evidences that urease inhibitors are effective in liver disease are still lacking.

Conclusion and future perspectives

Ammonia is the most common source of nitrogen available in the gut and given the fact that many microbial species produce and use ammonia in their metabolic processes, they play a crucial role in maintaining blood ammonia levels. Although meager, available experimental evidence strongly suggest that the intestinal microbiota is actively involved in the synthesis and breakdown of ammonia along with the host cells in liver physiology and pathophysiology. It is thus important to consider the contribution of gut microbiome towards ammonia production and systemic levels during liver disease. Different animal and patient studies have yielded varying results as the net result of gut microbial ammonia metabolism to plasma ammonia levels from a quantitative perspective varies according to many parameters like the nutritional status, liver disease severity, the animal model studied, the availability of the nitrogen sources, the composition and concentration of the microbiota, the overall metabolic capacity of the microbiota, the bowel transit time, the luminal pH, systemic glutamine levels, etc. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of many gut microbiota-targeted therapies in reducing hyperammonemia and cognitive impairments in cirrhosis affirms a key role of gut microbiome in ammonia production and utilization. We now need systematic investigations to delineate the precise contribution and mechanisms of increased ammonia production by gut microbial species to hyperammonemia in cirrhosis and HE. Microbiome-targeted therapy for lowering of ammonia levels in patients with HE has made substantial progress in last few years. However, the routine use of these generalized therapies such as FMT and antibiotics can also disrupt the beneficial effects of intestinal flora. In this regard, we need to focus on therapies that specifically reduce ammonia formation in patients with cirrhosis, for example targeting bacterial urease activity would be an ideal strategy to reduce ammonia production in a dysbiotic gut in cirrhosis.

Responses