Plasters from Jewish ritual purification baths in Late Hellenistic–Early Roman Palestine: composition, production areas, and anthropogenic residues

Introduction

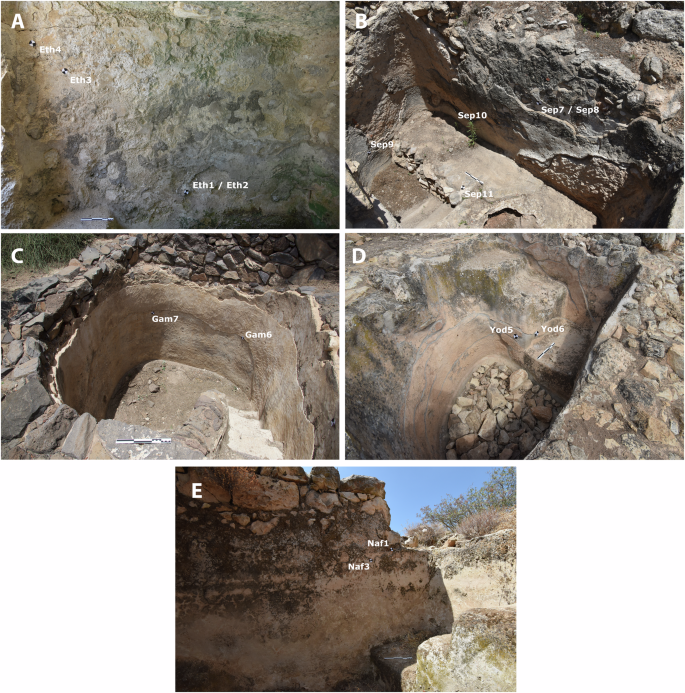

Stepped water installations dating to the Late Hellenistic–Early Roman periods dot the southern Levantine region, the area of modern Israel, Palestine, and western Jordan. Recent studies of these “stepped pools” suggest that there are several hundred examples, a large majority of them in and around Jerusalem (Fig. 1)1,2. In its basic form, a stepped pool is a rectangular, bedrock-hewn, plaster-coated installation, sometimes roofed, with a flight of steps spanning its full width (Fig. 2). It is fed, either directly or indirectly, by rainwater that is channeled from a building’s rooftop. No two of these stepped pools, however, are alike; they can vary greatly in terms of their size, shape, location within structures, and function. Most are attested in domestic contexts, although a small number are also found near tombs, roads, agricultural installations, and the Jerusalem Temple3.

Map of the southern Levant with the distribution of known stepped pools and locations of sampled sites (map by Rick Bonnie; data from ref. 1).

Sepphoris, stepped pool SP4 (photo by R. Bonnie).

Based on historical sources and structural characteristics, the consensus is that stepped pools functioned primarily as ritual purification baths for Jewish communities living in these areas, although other functions cannot be excluded4. By immersing in these pools, Jews could be purified from a state of impurity caused by, for example, contact with sexual fluids or diseases. The scholarly literature frequently refers to these Late Hellenistic–Early Roman stepped pools as miqva’ot (sing. miqveh, “gathering,” as in “gathering of water”; Lev 11:36), even though the first attestation of this term is dated after the second century CE5,6,7. Here we will generally use the term “stepped pool” to refer to this archeological feature.

Based on stratigraphic dating, stepped pools used for Jewish ritual purification first appeared during the late second or early first century BCE7,8, but by the end of the second century CE most of the hundreds that previously were in use had been abandoned or put to different use9,10. Due to their bedrock-hewn nature, however, the provided stratigraphic dates for these features remain imprecise (see, e.g., Table 1). Their dating has been solely established through their stratigraphic relation to other structures (construction phase) and through the materials from the pool’s lowest fill deposits (final [re]use/abandonment phase) [see ref. 9], much like cisterns11. Moreover, it should be noted that the stepped pools’ exact construction, use, and abandonment date considerably varies per site and structure. As can be seen from the dates of the structures examined in this study (Table 1), likely few of them were in use for much longer than a few generations, up to a century [see also ref. 12].

Recent studies of stepped pools have mainly focused on their purity functions and associated regulations in contemporaneous and later historical sources, most notably rabbinic literature4,8,13,14. In archeology, the focus has been on dating and understanding the introduction and cessation of the use or destruction of stepped pools across Jewish communities in the region7,8,9,10. Despite the general picture that we currently have of their chronological, spatial, and cultural context, we still know little about what type of people would have built such pools, and why, as well as how these stepped pools were constructed, used, perceived, and destroyed by different households. Essentially, aside from Galor’s work on the material from Qumran and Sepphoris5,6, stepped pools remain poorly understood in terms of their water function capabilities. This is in part due to a lack of integration with studies of water in antiquity in general, most notably research on rainwater-fed cisterns, which have similar structural characteristics11,15.

Few analytical studies have been done on stepped pools, apart from Ariel Shimron’s ICP-MS/AES investigation of plasters in stepped pools across various sites16,17,18, and recent studies on associated sensorial experiences19 or climatic effects on the functioning of these pools20. Similarly, little research on the plasters of ancient cisterns has been undertaken, especially in this cultural and geographical context11,21,22.

In this work, our aim was to characterize and compare the plaster compositions used in Late Hellenistic–Early Roman stepped pools at different archeological sites in the region. We integrated geochemistry and microscopy methods by applying wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (WD-XRF), inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), petrography and scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive spectrometry (SEM-EDS) to analyze plaster samples from stepped pools, as well as potential raw materials collected from the sites’ environs.

We examined patterns of inter- and intra-site variations in the plaster compositions based on the geochemical datasets and the microstructural and mineralogical characteristics of the plaster samples. We explored the hypothesis of local plaster production at the sites by seeking plaster compositions specific to certain sites; we also analyzed rock samples collected at each site. Furthermore, we evaluated the data patterns of both WD-XRF and ICP-MS datasets to identify anthropogenic chemical residues on the plaster surfaces indicative of non-water-related uses of the structures (e.g., industrial activities or storage). In addition, on-site, non-invasive portable XRF analysis on the sampled plaster surfaces was carried out to extend the analytical coverage for each structure to better explore intrastructural chemical variation. The pXRF-measured concentrations were compared to the laboratory-obtained data to evaluate the non-invasive plaster analysis approach.

Research materials

The archeological sites and sampled structures

For the present study, we selected 13 stepped, plastered pools from five archeological sites: Horvat ‘Ethri, Sepphoris, Gamla, Yodefat, and Keren Naftali (Fig. 1 and Table 1; see Supplementary Data 1 for sample context description). We selected these sites because of their good documentation on the stepped pools, contextualization, and accessibility. Moreover, the selected sites and sampled structures represent a variety of different material and cultural contexts in which stepped pools functioned, notably in domestic settings, but also near synagogues (Gamla) and fortresses (Keren Naftali). The sampled structures also represent the full chronological span in which stepped pools have been attested, from the early first century BCE (Keren Naftali) to the second century CE (Sepphoris).

Horvat ‘Ethri is a village site located in the Judean Foothills, about 35 km southwest of Jerusalem. Though founded in the late Persian Achaemenid period, archeological evidence shows that its heyday was in the first century CE23. The site was apparently abandoned after the First Jewish Revolt (66–70 CE) and again after the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132–135 CE), after which occupation slowly recovered until the fifth century CE. In addition to domestic structures, excavations exposed a larger public structure believed to be a synagogue, as well as four stepped pools. We sampled three of them. The fourth pool was not sampled because little plaster was preserved.

Stepped pool XI consists of a rock-cut, L-shaped staircase with seven steps descending into a square basin hollowed out of the bedrock (Fig. 3A). The basin includes two steps spanning the full width of the structure, with a narrower third step to the west. Stepped pool XI is located along the northern edge of an open courtyard adjoined by the believed synagogue and additional buildings. Channeling cut into the courtyard’s bedrock suggests that rainwater was received via the rooftops of the surrounding buildings. The courtyard’s central location suggests that this pool may have served a public function23. The pool was built during the first half of the first century CE and fell out of use in the early second century CE at the latest. During the Bar Kokhba Revolt it appears to have been reused for mass burial.

A stepped pool XI; B stepped pool XIII; C underground complex XV.

Stepped pool XIII is a somewhat smaller, hollowed-out square basin accessed from the north by a straight, narrow rock-cut staircase (Fig. 3B). The basin consisted of three steps spanning its full width, with a narrower fourth step along its eastern wall. The pool is located in a long, rectangular room situated off the open courtyard of a domestic structure. The pool was likely in use during the Early Roman period until the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

Underground complex XV included a stepped pool and cistern dating to the Late Hellenistic period that was damaged and then connected to one another sometime in Early Roman times (Fig. 3C)23. The excavators identified this rock-cut complex as a hideout for the village community during the two revolts. The complex was accessed via a stepped corridor cut into the corner of the believed synagogue (M1). Before the erection of M1, the corridor offered access into the stepped pool. When M1 was built, the earlier stepped pool was transformed into an entrance to the hideout and ceased to function as a pool.

Sepphoris is located in central Lower Galilee. During the first century BCE it served as a regional center, and later on, under Herod Antipas, became the capital of Galilee. The town gradually spread across the hill during the first century BCE and first century CE24. By the late first and second centuries CE the town grew rapidly. Excavations have revealed evidence of an orthogonal street grid with colonnaded streets, bathhouses, a theater, and a temenos temple complex dating to this period9,25. The Hasmonean and Early Roman settlement has so far not provided evidence of monumental buildings or grand public spaces; instead, it seems to have been dominated by traditional courtyard houses situated along narrow alleys. Within these dwellings, 25 stepped pools used for ritual purification purposes have been identified so far26,27, of which we sampled four. The functions of eight other pools found within these dwellings remain uncertain.

Stepped pool SP2 (Fig. 4A) had five steps, the upper two of which are not preserved, leading down into it from the east. A sixth, narrower step was situated at the bottom center of the pool. The pool, located against the mouth of an earlier cistern (C1a) and fitted within a preexisting enclosed space, was part of a larger peristyle house (Unit Ib) attributed to the mid-to-late first century CE26,28. It was accessed from the east, where it has been suggested that a series of rooms ran along an open courtyard. Ceramics from the lowest accumulated deposits in the pool, as well as later modifications, suggest that the pool fell into disuse by the early second century CE at the latest28.

A Sepphoris SP2; B Sepphoris SP4; C Sepphoris SP8; D Sepphoris SP17; E Gamla L1060; F Gamla L1293; G Gamla L3105; H Yodefat no. 1; I Yodefat no. 2; and J Keren Naftali Sq. D.

Stepped pool SP4 (Fig. 4B) consisted of an underground basin accessed through an L-shaped descent, with four steps descending westward and another four northward. A paving stone near the pool’s first step contains a pierced hole, 4 cm in diameter, that probably functioned as a water conduit. The pool is located in a house (Unit II) built around the turn of the common era and still in use in the Byzantine period26,27. Its room, which also accommodated a preexisting rectangular barrel vault and a contemporaneous cistern, gave access to a corridor that linked to a room associated with food processing activities. Finds from the pool’s fill suggest that it fell into disuse by the early to mid-second century CE29.

Stepped pool SP8 (Fig. 4C) originally consisted of seven steps leading into a larger basin. The pool was later reconfigured into a larger dry-storage area through the removal of several of its steps. It is located along the northern section of a first-century CE house (Unit IVc) and served as a corridor accessed from the south via a row of rooms26,27,30. The pool can generally be attributed to the Early Roman period26.

Stepped pool SP17 (Fig. 4D) consisted of an L-shaped descent, with one or more unpreserved steps descending northward and another four steps westward26,27. It was part of a complex of various water installations built over a preexisting cistern, including the 25-cm wide mouth of that cistern, an open plastered channel, and a square plastered basin. However, no apparent water connection between stepped pool SP17 and the rest of the complex has been preserved. The complex was part of an only partially uncovered, Early Roman dwelling (Unit VIIb). Early to Late Roman pottery from the pool’s fill suggests that it fell into disuse sometime in the second to mid-fourth centuries CE31.

Gamla, situated in the southern Golan, preserves the remains of a Late Hellenistic–Early Roman hilltop settlement overlooking the Sea of Galilee. The site developed as an administrative center from the early first century BCE until its destruction by Roman troops during the First Jewish Revolt32. Excavations have exposed the remains of domestic buildings, agricultural and industrial installations, and an early monumental synagogue. We sampled three stepped pools at this site. A fourth pool was unavailable for sampling due to a recent collapse.

Stepped pool L1060 (Fig. 4E) was, in its original phase, a larger rectangular basin consisting of four outer walls. At a later date, an additional wall and steps were added along its southern side, while a stabilizing retaining wall was added against its northern wall. All additions show several layers of plastering. The pool apparently received water from two large cisterns outside the Gamla town wall33, which were connected via a plastered channel (L1024) running through the interior of a nearby synagogue, emptying first into a small square, plastered basin (L1062) that presumably functioned as a settling pool. Stepped pool L1060 was situated about 4.5 m away from the synagogue’s facade. Its orientation and evidence of water channels suggest that it was closely associated with the synagogue33. The pool’s exact dating remains unknown, but based on this association a first-century CE date can be assumed.

Stepped pool L1293 is a large, deep oval structure (Fig. 4F) with a staircase and railing along its northern side34. It was accessed from a vestibule area to its south. The pool was apparently fed by rainwater gathered from an adjacent road built on a higher-level terrace plateau. Excess water was diverted via plastered overflow channels that ran further westward across the vestibule and entrance areas. The pool was built in the early first century BCE, with further structural changes to its surroundings (incl. three additional steps) in the late first century BCE. By that time, evidence from complete storage jars recovered therein suggests that the pool had changed into a storage area or refuse pit34,35.

Stepped pool L3105 is a relatively small rectangular structure (Fig. 4G) accessed via a staircase running along its southern and western walls. It dates to the first century BCE34. In a later phase, an unplastered wall was added to the basin, effectively making it unusable for water storage. The basin may have been reused for dry storage, but it is unclear how it could have been accessed without a usable staircase.

Yodefat was a hilltop settlement located in central Lower Galilee. Established in the Hellenistic period, the settlement was turned into a defensive stronghold in the late second century BCE. Material remains indicate that the village prospered during the first century BCE and first century CE, up until its destruction during the First Jewish Revolt36. We sampled both excavated stepped pools from the site. Stepped pool no. 1 (Fig. 4H) consists of six rock-cut steps that descend counterclockwise. Five successive layers of plaster have been identified. The pool lay alongside a cistern and partially below a settling pool, both of which predated the stepped pool. The pool was part of a partially exposed domestic structure. Stepped pool no. 2 (Fig. 4I) is a small, stone-built structure with three steps that was part of an L-shaped series of four domestic rooms. Its exact date remains uncertain, but the domestic structure and this pool apparently predate the other domestic structure (including stepped pool no. 1) located directly to the south.

Keren Naftali, situated on a steep, isolated hill in eastern Upper Galilee, preserves the remains of a large Late Hellenistic/Hasmonean fortress with eight rectangular towers37. The single-stepped pool (hereafter Sq. D) uncovered at the site is located in the western part of the fortress (Fig. 4J). The relatively large basin can be accessed via L-shaped stairs running along its northern and western sides. Pottery from the lowest fill deposits date the stepped pool to the late second or early first century BCE, while the upper fill deposit suggests that it fell into disuse during the mid-first century BCE to mid-first century CE, after which it served primarily as a refuse pit.

Methods

Sampling and integrated analytical strategy

We combined geochemical analysis of powdered samples with mineralogical and micro-structural cross-section analyses to define plaster compositions, recipes and technologies. For geochemistry, wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (WD-XRF) and ICP-MS were carried out at the Washington State University GeoAnalytical Laboratory. WD-XRF was mainly used to determine major and minor elemental concentrations of the plasters38,39,40, while ICP-MS was employed for trace element and rare earth element (REE) data acquisition41,42,43. In addition, non-invasive, energy-dispersive portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (pXRF)44 was used on-site at the sampling locations to extend the analytical coverage of the examined structures to gain better representation of the possible intrastructural compositional or residual variation of the plaster surfaces.

Selected samples were subjected to petrographic analysis and SEM-EDS to assess the mineralogy and binder and aggregate materials of the plasters, carried out at the UCL Institute of Archaeology laboratories45. Furthermore, rocks collected from the sites were included in the sample set as potential source materials. Loss on ignition (LOI) percentages indicating the level of carbonization of the powdered samples are reported in Supplementary Data 2.

On site, the chosen sampling spots of the plaster surfaces were cleaned with a brush and the scientific samples were taken with a chisel and hammer. Approximately 5 g of material was removed from the plaster at each sampling position. The sampling was carried out on seemingly well-preserved plaster surfaces, and sampling next to cracks and holes in the plaster was preferred in order to minimize damage to the archeological structures (Fig. 5; see Supplementary Data 1 for sample location descriptions). Prior to further processing, the samples were documented by taking photographs (Fig. 6) and examined macroscopically and microscopically using a Leica M80 stereomicroscope to determine the grain size and variability of the aggregate materials in the plasters.

A Horvat ‘Ethri; B Sepphoris; C Gamla; D Yodefat; E Keren Naftali.

A, B gray (ETH2) and white (ETH3) plaster layers from Horvat ‘Ethri stepped pool XI; C floor plaster (SEP4) from Sepphoris SP4; D plaster containing shell (SEP11) from Sepphoris SP8; E plaster with basalt aggregate (GAM1) from Gamla stepped pool L1060; F fine-grained, reddish plaster on bedrock (YOD1) from Yodefat pool no. 1; G shell containing plaster (YOD3) from Yodefat pool no. 1; H pink surface layer (NAF3) from Keren Naftali stepped pool Sq. D.

Overall, the samples of plaster and raw material (limestone from the vicinity of each archeological site sampled as well as basalt from Gamla) subjected to the analysis presented relatively homogeneous and small-grained matrices, the maximum grain size being 2–5 mm for all of the samples other than two from Horvat ‘Ethri (ETH7–8), which had 7–8 mm limestone inclusions, and one from Gamla (GAM1) with basalt inclusions of less than 8 mm. It was common in the Roman period to mix lime with crushed pottery and bricks (cocciopesto) to produce plaster—especially for hydraulic constructions, but also for floors and other non-water-related surfaces46,47; grog and other argillaceous aggregates were reviewed under the petrographic and scanning electron microscopes.

WD-XRF and ICP-MS results were acquired for the entire dataset of 54 plaster samples, of which 15 plaster samples and five rocks, from each of the five sites and the geochemical groups indicated by the WD-XRF and ICP-MS data, were prepared as thin-section and petrographically examined. Finally, five of these plasters were also examined with SEM-EDS to gain geochemical data on the binder composition and aggregate materials. The analytical datasets obtained were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 software. Multivariate statistical tests (cluster and principal component analyses) were performed and various bi/multi-element dataplots of elemental concentrations were produced in order to investigate and best visualize the structures and trends present in our datasets.

Geochemical analysis of plasters via WD-XRF and ICP-MS

ICP-MS and XRF are bulk chemical methods unable to discriminate between aggregates and binders in plaster samples, hence, these methods were applied exclusively to characterize the plaster mixture concentrations and chemical enrichment on plaster surfaces, whereas the plaster micro-structures, mineralogical composition, and geochemical characterization of plaster binder and aggregates were carried out via microscopy analysis (see below).

For the laboratory-XRF data, a ThermoARL Advant XP+ sequential X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (Rh target run at 50 kV and 50 mA with full vacuum and a 25 mm mask for all elements) was used on powdered samples (~3.5 g) formed into fused beads. A low-dilution fusion method was used to correct matrix effects for major and trace elements. Data was obtained for 10 major and minor elements and 19 trace elements48. The laboratory reports with acceptable accuracy and precision values for WD-XRF-measured concentrations above 30 ppm; for lower concentrations, and for Sc, V, Nb, and Ba values compromised by the analytical settings, ICP-MS data were used.

For the ICP-MS data acquisition, an Agilent 7700 ICP-MS was employed, after ~2 g of powdered sample material was diluted in keeping with established procedures. A combined fusion-dissolution method was used: low-dilution fusion with di-Lithium tetraborate and open-vial mixed acid digestion, enabling the decomposition of refractory mineral phases and the elimination of matrix effects, and in effect the analysis of 14 REEs and 13 trace elements49. The laboratory reports a long-term precision for the method of better than 5% (RSD) for the REEs and 10% for other trace elements.

Non-invasive pXRF analysis of plaster surfaces on-site

The handheld portable XRF instrument utilized for the non-invasive chemical characterization of plaster layers on-site was a Bruker S1 Titan owned by the Archaeology Laboratory of the University of Helsinki. The instrument, equipped with a silicon drift detector and an Rh-target X-ray tube, has a spot size of 8 mm and was operated in-air using a Geochem trace calibration mode, with a total acquisition time of 120 s. We performed 5–8 pXRF measurements per sampled structure on seemingly well-preserved plaster surfaces in addition to the invasive sampling.

In-air XRF analysis of unprepared, heterogeneous samples cannot provide fully quantitative results38,50,51,52,53; thus low Z element concentrations (the main constituents of plaster) cannot be detected in this way. However, non-invasive pXRF has been proven to perform fairly well in analyzing high Z (≥26) element concentrations even in unprepared samples44,54,55,56,57,58. Therefore, we wanted to test the suitability of pXRF as an additional on-site tool in plaster analysis for identifying variations or anomalies in heavy-element (Z ≥ 26, Fe) concentrations of plasters. Although this application has its limitations, e.g., matrix and surface effects, and detection limits are higher than with more sensitive techniques, it can prove useful especially when sampling is restricted.

Petrographic and SEM-EDS analysis of plasters

Subsamples of 15 plasters and five rocks were cast in resin blocks and then prepared as 30 μm petrographic thin sections following modified standard geological technique59, examined under the polarizing light microscope at 40–200× magnifications. Five of these plaster samples, from each site and compositional group, off-cuts from the thin-section preparation, were polished flat with carborundum and diamond paste (down to 1 μm) and studied using Carl Zeiss EVO 25 SEM instrument with an Oxford Instruments X-max 80 EDS spectrometer housed at the UCL Institute of Archaeology to characterize the chemical compositions of the binder, aggregate particles, and possible external layers45. The reported results per feature are normalized wt% averages of at least three analyses at 150× magnification (oxygen by stoichiometry). Aztec 4.1 software was used for data extraction and interpretation. The SEM operating conditions were: high vacuum, accelerating voltage 20 kV, beam current 60 pA, working distance 8.5 mm, standardization deadtime 40–50%; a cobalt standard was applied for beam stability control and internal calibration of the instrument. Measured values for standard reference materials BHVO-2 Basalt Hawaiian Volcanic Observatory and BCR-2 Basalt, Columbia River, analyzed for the SEM-EDS data accuracy and precision, show relative errors ≤2% for Na2O, MgO, Al2O3, SiO2, and CaO, and ≤8.5% for K2O, TiO2 and Fe2O3.

Results and discussion

In this section, we report the analytical data for 54 samples analyzed via WD-XRF and ICP-MS, including 44 archeological plaster samples (11 from Horvat ‘Ethri, 14 from Sepphoris, 9 from Gamla, 6 from Yodefat, and 4 from Keren Naftali) and 10 rock samples (2 limestone samples from Horvat ‘Ethri, 1 limestone from Sepphoris, 2 limestone and 1 basalt from Gamla, 2 limestone from Yodefat, and 2 limestone from Keren Naftali), petrographic microscopy results for 15 of the plaster samples and five of the rocks (one per site), and geochemical SEM-EDS data for five of the plaster samples. The results will be discussed following our research aims, with a focus on identifying plaster compositions and recipes at the sites based on bulk chemical profiles and technological characteristics of the plasters, indications of different material source areas in the trace elemental signatures and mineralogical contents of the plasters, and potential anthropogenic chemical residues on the plastered surfaces.

Compositional and technological characterization of plasters used at the sites

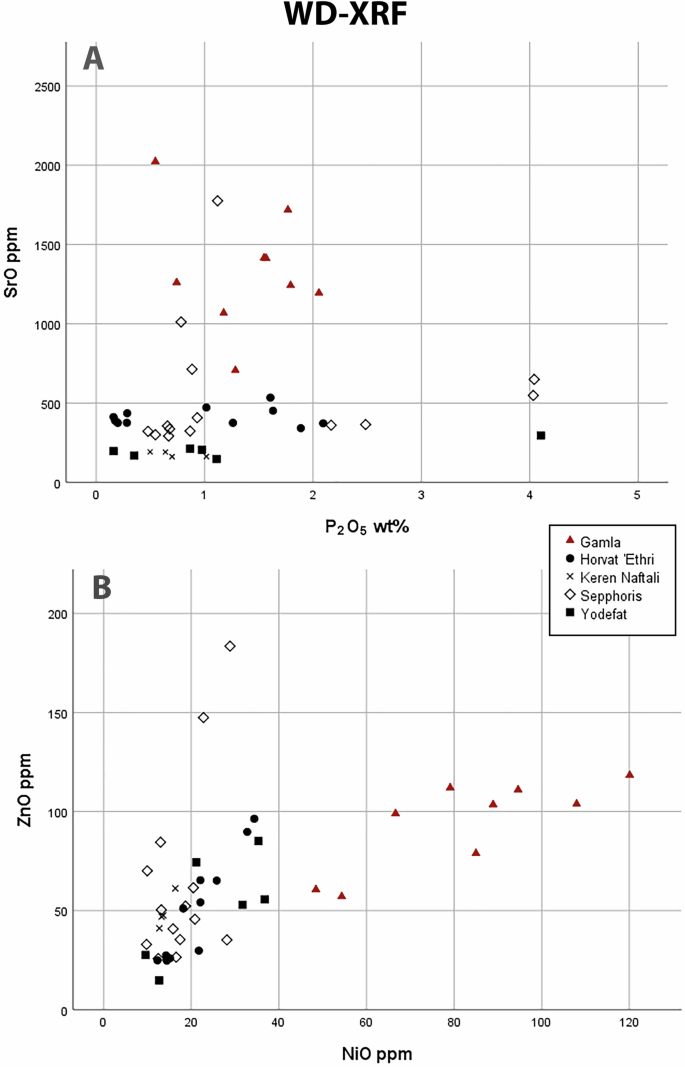

The main chemical components of the plasters detected via WD-XRF are SiO2, CaO, MgO, FeO, Al2O3, Na2O, and K2O (Table 2). In inter-site comparison, the Gamla samples have relatively high concentrations of SiO2 (27–40 wt%) and low concentrations of CaO (<53 wt%), whereas the plasters from the other four sites in general display lower SiO2 values at 10–30 wt% and higher CaO at 60–85 wt% (Fig. 7A, Table 2). The Gamla plasters also differ from those at the other sites in terms of their TiO2, K2O, Al2O3, FeO, and MgO concentrations, which are consistently higher than the dataset average (Fig. 7B, C, Table 2). The compositional correlation between the Horvat ‘Ethri, Keren Naftali, Sepphoris, and Yodefat samples is related to the location of these sites in similar geological settings in limestone prevalent areas, whereas Gamla, in the Golan Heights, is positioned in a different geological context (see discussion on the influence of local geology on the results below).

A CaO vs. SiO2; B TiO2 vs. K2O; and C Al2O3 vs. FeO.

The similarities in the plaster compositions from the four sites cannot, however, be explained by geological relationships alone. Plasters are man-made mixtures of materials, and therefore in chemical bulk analysis their main compositional characteristics reflect the recipes followed in their production more than the raw materials, e.g., limestone, that were used18. It can be difficult to identify the sources of limestone used for their production46. This is apparent when we compare the major element concentrations in the plasters to those of the rocks analyzed from the sites: there is a greater correlation between the plasters, even coming from rather distant sites, than between plasters and limestones from the same site. Thus, intersite correlation of plaster compositions, especially in this fairly narrow chronological setting, can be interpreted as signaling similarities in the plaster manufacture processes, and particularly in the recipes used (Fig. 8A, B; see rock composition data in Table 2).

A CaO+MgO vs. Al2O3+FeO (wt%); and B SiO2+Al2O3+FeO vs. TiO2 (wt%).

In terms of mineralogy and aggregates of the plasters, samples from Horvat ‘Ethri, Sepphoris, Yodefat and Keren Naftali show related characteristics: ten of the 14 plaster samples examined petrographically from these four sites show elongate opaque wood or charcoal flakes (most prominent in samples ETH1–2, SEP12–13, YOD2–3 and NAF1; Fig. 9A–E). The abundance of these materials indicates that they were intentionally added, perhaps also as a colorant in the plaster59. Moreover, samples from the four sites also present red-brown argillaceous mud/earth-based materials (Fig. 9C), potentially crushed ceramics (Fig. 9E). Clay-based materials are sometimes added in plasters in hydraulic lime production to advance setting of the plaster in damp conditions, but are also common aggregates and colorants in plasters in general59. The pinkish hue, e.g., in Yodefat samples YOD1–6 may result from the abundance of the argillaceous materials in their mixture. Microfossils found e.g., in sample YOD5 suggest that limestone was added as an aggregate; abundant shell in SEP13, and to a lesser extent in ETH1 and NAF3; also rare bone fragments are encountered in SEP12 and SEP13. Silicate minerals are rare in the samples. In contrast, the plaster sample examined microscopically from Gamla, GAM1a (sample taken c. 0.8 m above geochemical sample GAM1), is the only plaster to present basalt aggregates, randomly oriented plagioclase laths and olivine and pyroxene phenocrysts (Fig. 9F). The Gamla plaster is also without the woody/charcoal and argillaceous materials described above.

A ETH1 from Horvat ‘Ethri, B SEP12 from Sepphoris, C YOD1 and D YOD3 from Yodefat, E NAF1 from Keren Naftali, F GAM1a from Gamla, G NAF3 from Keren Naftali, and H YOD6 from Yodefat. All images were taken in crossed polars, image width 2.9 mm (credit P. S. Quinn).

In terms of local recipes, the six plaster samples examined petrographically from Yodefat all share the characteristics of argillaceous materials, and micritic limestone and charcoal flakes aggregates. The Keren Naftali plasters also share similar aggregate materials, limestone, argillaceous materials, and lime lumps. The Keren Naftali plasters are differentiated from the Yodefat samples for the rarity of charcoal flakes and their limestone aggregate presents more allochems and sparry calcite. Apart from the Gamla plaster, the most common aggregate is limestone, the characteristics of which vary between the sites and plaster samples. In most cases, the rocks sampled at the sites match aggregate materials in the plasters from the corresponding sites, but the plasters present also other materials. Silicate minerals and rocks are rare, apart from the basalt aggregate Gamla plaster, whereas limestone was the preferred aggregate, demonstrating, among the other characteristics, that a shared tradition of plaster manufacture was followed at several individual sites.

The binder in most of the analyzed plaster samples is fine micritic calcite (Fig. 9G), purer lime is shown in e.g., samples NAF1 and YOD6 (Fig. 9E, H), whereas in plasters rich in argillaceous materials the binder has a reddish hue. Gypsum crystals were not identified in binder under the petrographic microscope, and this conclusion is supported the lack of sulfur in any significant concentration in the binder (<1 wt%). The geochemical binder analysis carried out via SEM-EDS (Supplementary Data 5) for five of the plaster samples confirms the high CaO content, c. 70 wt% on average, of the binder, added by varied concentrations of SiO2 and Al2O3, and minor concentrations of Na2O, MgO, K2O, and Fe2O3—most probably deriving from binder preparation by mixing lime with argillaceous materials. The samples show low or moderate porosity, though it is noteworthy that sample YOD1 shows significant porosity possibly linked to dry slaking (Fig. 9C).

The bulk chemical relatedness of the Horvat ‘Ethri, Keren Naftali, Sepphoris, and Yodefat plasters indicating similar plaster technologies and recipes is supported by the findings of the microscopic analysis, namely the use of lime binder and similar aggregate materials, limestone, argillaceous materials and charcoal flakes. Hence, we can conclude that there are clear technological similarities in the recipes of the plasters from these sites. Lime lumps indicate that lime was used as a binder, as gypsum was not found in the samples. Lime was mixed with argillaceous materials (earth/clay/crushed pottery), probably also serving as a colorant for the pink-hued plaster or as a pozzolanic aggregate.

The two Horvat ‘Ethri plasters (ETH1–2) studied petrographically are compositionally related, and show technological similarities, with Yodefat, Keren Naftali, and Sepphoris plasters—they contain charcoal flakes, argillaceous materials, and micritic limestone lumps as aggregates. The Sepphoris plasters (SEP12–13) show characteristics related to Yodefat and Keren Naftali plasters, namely abundant argillaceous and charcoal flake aggregates, micritic limestone, lime lumps, and rare bone; SEP13 also contains shell aggregate.

The abundance of the charcoal flakes suggests their intentional addition, perhaps to achieve the grayish color. The Gamla plaster sample analyzed petrographically (GAM1a) is differentiated from the plasters from the other sites due to its basalt aggregate. Moreover, it lacks charcoal flakes and argillaceous materials and its lime lumps in its lime binder are rare, while there are some micritic and sparry limestone aggregate. The higher SiO2 and lower CaO levels of the Gamla plasters compared to the plasters from the other sites derive from the use of basalt aggregate instead of limestone. The basalt aggregate probably also explains the higher TiO2, K2O, Al2O3, Fe2O3, and MagO values.

There are also noteworthy intrasite and particularly intrastructural phenomena in the plaster recipes. It appears that at least in some of the pools at Horvat ‘Ethri, Sepphoris, and Yodefat different plaster recipes were used in different layers or parts of the structures. For example, in stepped pool XI at Horvat ‘Ethri, the topmost gray plaster (ETH1–2) shows higher SiO2 (15–20 wt%), Al2O3, FeO, Na2O, and K2O and lower CaO (<71 wt%) concentrations compared to the values measured from the lower, white plaster layer (ETH3–4 with, e.g., SiO2 ≤ 12 wt% and CaO ≥80 wt%). The topmost, gray plaster was also examined microscopically and presents similar aggregate (micritic limestone, argillaceous material, charcoal flakes) and binder characteristics. The elevated SiO2, Al2O3, FeO, Na2O, and K2O, and lower CaO values in one of the plasters may derive from higher proportion of argillaceous materials in that plaster sample.

Similarly, one of the three samples from the Horvat ‘Ethri complex XV cistern (ETH11) is compositionally more similar to the top layer of stepped pool XI than the other plaster layers from the same structure. In Sepphoris, some of the disparity in the measured values for each structure may be explained by in-recipe variation (see, e.g., samples SEP1–3 from structure SP2), but there are also clear anomalies, especially the white plaster layers in structures SP4 and SP17 (samples SEP6 and SEP14, respectively) and the floor plaster in SP8 (SEP11), all of which display lower SiO2 (<8.6 wt%) and higher MgO and CaO values than other samples from these structures and from Sepphoris in general. In the microscopic analysis, the Sepphoris in-recipe variation attested by the bulk chemistry values is shown in the abundant shell aggregate of SEP13, while the shell is less frequent in SEP12.

The plasters from Gamla do not show significant intrasite or intrastructural variation, but the samples representing the cream-colored plaster layer of stepped pool L1293 (GAM6–7) show slightly lower SiO2, Al2O3, and FeO and higher CaO concentrations than those measured in the white plaster (GAM8–9) of this structure. In Yodefat stepped pool no. 1, the fine-grained, reddish plaster layer applied on the bedrock (YOD1) has a lower SiO2 content (5 wt%) and higher MgO (13 wt%) and CaO (78 wt%) values than the other samples from this pool or Yodefat stepped pool no. 2. The concentrations measured from the cocciopesto plaster in Yodefat stepped pool no. 1 (YOD3) fall close to the average values for the site, although the layer has anomalous phosphorus levels at 4 wt% (which are probably unrelated to the grog).

The occurrence of intrastructural differences between plaster layers at several sites is indicative of the selective use of plaster recipes for different functions, e.g., to be applied directly on bedrock, as the topmost surface layer, or as a floor surface in contrast to walls. Increased SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe content can also affect the hydraulic properties of the plasters and enhance their durability60,61,62. According to a common formulae applied to calculate the hydraulicity index (HI)63, based on the relative proportions of Ca and major and minor concentrations in the binder, it cannot be concluded with certainty whether the plasters were of hydraulic materials (to set in wet conditions), however, this may have been the case at least for SEP13 and YOD345 (Supplementary Data 5).

In some structures, however, different layers made from the same recipe are clearly visible. For example, the samples analyzed from Keren Naftali stepped pool Sq. D (NAF1–4) are compositionally closely related, although a finer-grained mixture was chosen for the surface layer. Furthermore, in Horvat ‘Ethri stepped pool XIII only one plaster recipe was used for all layers. The use of single/multiple recipes may be related to the building processes for the structures, or, alternatively, the different plaster technologies may be related to different building phases of the sites and may represent chronological differences between the sites64,65. The possible replastering of structures in cases where several chemically different layers are present cannot be ruled out either.

Sourcing plaster materials by trace elemental signatures

The sampled sites are situated in three different geological settings. Keren Naftali, Yodefat, and Sepphoris are located on Cretaceous to Early Tertiary limestones. Keren Naftali and Yodefat are both located on the Deir Hanna and Sakhnin formations, belonging to the Upper Cretaceous Judean Group66,67. The Deir Hanna formation consists of alternating beds of chert-containing limestone and chalk, as well as thin dolostone beds66,68; the Sakhnin formation consists of thick, gray dolomitic limestone beds68,69. Sepphoris is located on the border of the Late Cretaceous–Early Tertiary fossil-rich chalks and marls belonging to the Mount Scopus Group and the Sakhnin dolostones67. Horvat ‘Ethri, on the other hand, is located on massive chalks, which are part of the Tertiary Adulam formation70. Gamla is located in the Golan Heights, on the eastern side of the Jordan Rift Valley, where the bedrock consists of massive Pliocene (Upper Tertiary) basalt dating from the formation period of the Rift71,72. Basalts are igneous volcanic rocks whose main components are pyroxene, plagioclase, and olivine. As a result of their mineralogy, basalts are richer in MgO and CaO and lower in SiO2 and alkali oxides than other igneous rocks.

The main component of limestone is CaCO3. In dolomitic limestones, the Ca is partially replaced by Mg, which forms ~43% of the dolostones in the Sakhnin formation69. The rock samples from Sepphoris, Yodefat, and Keren Naftali all contain roughly 23–40% MgO and 50–70% CaO, indicating that these samples represent dolomitic limestone. The rock sample from Horvat ‘Ethri, in contrast, is nearly pure calcite, with a CaO content of >93%, reflecting the different bedrock settings of that site. The element concentrations in the basalt sample from Gamla are in line with the results of ref. 73 for Golan basalt. The Gamla limestone samples contain 28–29% MgO and 50–53% CaO, but also relatively high SiO2 (c. 10–14%), suggesting a dolomitic limestone with chert or clay content. Further to the west, along the same wadi near which Gamla is situated, there are also exposures of the underlying earlier Tertiary Gesher formation, which consists of limestone beds overlaying marl and clay. These exposures form the closest mapped source of limestone for Gamla. Due to limited access to the area, we did not sample this limestone exposure.

Petrographically, the limestone sample from Yodefat (YOD8), is homogeneous fine-grained and micritic, presenting some recrystallization and no allochems (Fig. 10A). Fine micritic limestone is present in all Yodefat plaster samples examined petrographically, supporting the hypothesis of local plaster manufacture at the site. The limestone rock sample from Keren Naftali (NAF5, Fig. 10B) shows fine sparry calcite crystals, an aggregate of this type is found at least in Keren Naftali plasters NAF2–3, among diverse limestone materials in the plasters. The limestone rock sample from Sepphoris (SEP15, Fig. 10C) shows fine sparry calcite crystals and no allochems, its material does not match those of the studied plasters from the site. The rock sample from Horvat ‘Ethri (ETH12, Fig. 10D) is fine, micritic limestone with abundant foraminifera microfossils, similar to materials present in the plasters from the site. The rock sample from Gamla (GAM10, Fig. 10E) is fine micritic limestone that lacks microfossils and allochems, similar to limestone grains found in the Gamla plaster.

A YOD8 from Yodefat, B NAF5 from Keren Naftali, C SEP15 from Sepphoris, D ETH12 from Horvat ‘Ethri, and E GAM10 from Gamla. All images were taken in crossed polars, image width 2.9 mm (credit P. S. Quinn).

Our hypothesis, based on the location of the sites in a limestone region and the sampling of mainly household-context plasters, was that local raw materials were exploited in the plaster technologies of the communities under scrutiny here, although long-distance plaster aggregate transport is known, e.g., from medieval Italy60,74. As discussed above, the major element ratios in plasters do not correlate with those of the rocks used as raw material due to material mixing in plaster preparation. However, focusing on trace elements and especially REE compositional signatures in plaster mixtures and local rocks can provide more useful results for linking plaster chemistries with the local geological characteristics60,75,76.

Significant similarities and overlap were seen between the major compositional patterns, i.e., the plaster recipes, from Horvat ‘Ethri, Sepphoris, Keren Naftali, and Yodefat. However, it is apparent from Fig. 11A–C that these are all distinct recipes, manufactured from different, albeit geologically related raw materials (i.e., the limestone located in the vicinity of each site, or different aggregate materials, e.g., ash, shells, dung, pottery). In terms of sourcing, the relationships between the plaster and possible parent limestone from the sites can be seen especially in the La/Ce vs. Yb diagram for Yodefat (Fig. 11A), in the Ba vs. La/Ce diagram for Horvat ‘Ethri and Keren Naftali (Fig. 11B), and in the Sr vs. Y/Nb diagram for Sepphoris, Gamla, and Yodefat (Fig. 11C). The ratios show clear assimilation in the trace and REE concentrations, but not exact matches between the sampled plasters and rocks. Although the differences can be explained by the mixing of raw materials in the plaster preparation process, it should be also noted that the rock samples do not always represent the direct source of the plaster; rather, they may represent rocks from related geological environments.

A Yb ppm vs. La/Ce; B Ba ppm vs. La/Ce; and C Sr ppm vs. Y/Nb.

The MgO and CaO content of the plasters from Yodefat, Keren Naftali, and Gamla fit the composition of dolomitic lime77 (see Table 2), suggesting that the rock samples collected at the sites likely represent the parent rock of the lime used in the plasters. The plaster samples from Sepphoris, however, have a clearly different chemical composition than the bedrock sample to the east of the archeological park: the lower MgO content and CaO content of approximately 63%–88% suggest that a different source rock was used. All of the sampled limestones were poor in SiO2, Al, Fe, and Zr, with the exception of those from Gamla. The concentrations of these elements in the plasters therefore likely reflect aggregates high in SiO2, such as sand or grog. The dolomitic limestones also tend to be poor in P and Na, and Sakhnin dolomites poor in Fe and Mn have been found. Ba, Zn, and Y have also been found to be relatively low in dolostones69. The high Ba in the Gamla plaster samples probably derives from basalt used as aggregate in the plasters.

The Sr content of limestones and dolomites varies considerably78, which suggests that Sr can be a useful element for sourcing limestones. As a rule, our rock samples from Sepphoris, Yodefat, and Keren Naftali were characterized by relatively low Sr content, whereas our Horvat ‘Ethri samples had a considerably higher Sr content. The Gamla samples also exhibited a very high Sr content. The Sr content of the rock samples was also reflected in the plaster composition at the different sites, suggesting that lime was obtained locally—except, notably, at Sepphoris. The Sr content of the plaster from Sepphoris was considerably higher than in the rock sample. High Sr is typical of Upper Cretaceous to Tertiary limestones and marls79, which suggests that these, rather than the dolomitic limestone sampled at the eastern end of the site, form the parent rock for the lime used in Sepphoris plasters. A survey and sampling of the different limestones in the vicinity of the site would be needed to identify the probable source.

The REE content in limestones is mainly related to the input of continental material in the sediment. In earlier research, Cretaceous limestones were generally found to be poorer in REEs than Tertiary limestones. The lowest REE content is associated with dolomitic rocks. In Upper Cretaceous and Early Tertiary marls with a high clay content the REE content is higher, reflecting the impact of clay minerals73,80. Basalts also have considerably higher occurrences of REEs than limestones and dolostones, reflecting their igneous origin and mineral composition. The results from the analysis of the REE concentrations in our rock samples match those of73 for Judea Group limestones and Golan basalt; i.e., the limestones and dolostones have low REE concentrations, and thus the lime is not the main source for the REE observed in the plaster samples. The Gamla limestones exhibit higher REE than the other samples; this is consistent with the probably aggregate-derived higher SiO2.

We compared the La/Ce and Y/Nb ratios with ppm concentrations of Yb, Ba, and Sr as measured in the plasters and rocks collected from the sites (see binary diagrams of ICP-MS data in Fig. 11A–C; see also Table 3) in order to compositionally group the analyzed samples and source plasters based on similarities with local rocks. The La/Ce ratio in particular has been found in previous research to function well as a discriminating parameter differentiating between limestone sources60,61,76,81. The limestones sampled, except for those from Gamla and Horvat ‘Ethri, group relatively close together, probably reflecting their geographical vicinity, whereas there is more variation in the plasters, probably reflecting the addition of different aggregates to the plasters.

Trace elements or REEs are not detectable via SEM-EDS, thus the chemical signatures of the limestone aggregates or lime in binder of the plasters cannot be comprehensively detected. However, the MgO values measured for SEP13 and YOD3 binder support the conclusion of burning dolomitic limestone to produce lime for the binder of these plasters.

The water stored and used in the stepped pools is primarily from surface runoff, i.e., rainfall collection, and the plaster should prevent contact and leaching from the adjacent bedrock. Therefore, the water composition in the pools could be expected to reflect both rainfall and dissolution from the plaster itself. Thus, most of the REEs observed in the analyzed plasters likely reflect the aggregates added to the lime (sand, shells, and crushed pottery) as well as possible enrichment from the water and contamination from later uses of the structures. In Gamla, the REE concentrations closely resemble those of the local basalt, suggesting that the aggregate materials used in the plaster had the same mineral composition as the basalt rock and were locally obtained.

Identifying anthropogenic chemical residues on the plastered surfaces

In order to identify and interpret use-derived, anthropogenic chemical residues on the plaster surfaces, possibly indicative of non-water-related functions of the pools, anomalous concentrations in the analytical datasets were investigated. In the literature, increased phosphate levels on surfaces of structures have been linked to the preparation or storage of foods rich in phosphates, as well as to exposure to food waste and fecal waste82,83,84,85. Enrichment in Ca, K, Mg, Fe, Mn, and Sr can be seen as “directly reflect[ing] anthropogenic chemical residues”86. Concentrations of Ba, Zn, Sn, Be, Ag, Cu, Pb, Sb, Hg, Ni, Th, and As might indicate contamination by industrial activities, e.g., copper or lead exploitation, or storage of metal goods82,86,87,88,89. However, identifying anthropogenic residues in archeological structures with certainty is complicated, and floor contexts have also shown that Cr, Mg, Ni, Pb, and Ti patterns can derive from a site’s geological background86. The high Sr and Ba values in our Gamla samples most likely derive from the geology of the region. Possible contamination by modern materials should also be considered16,82.

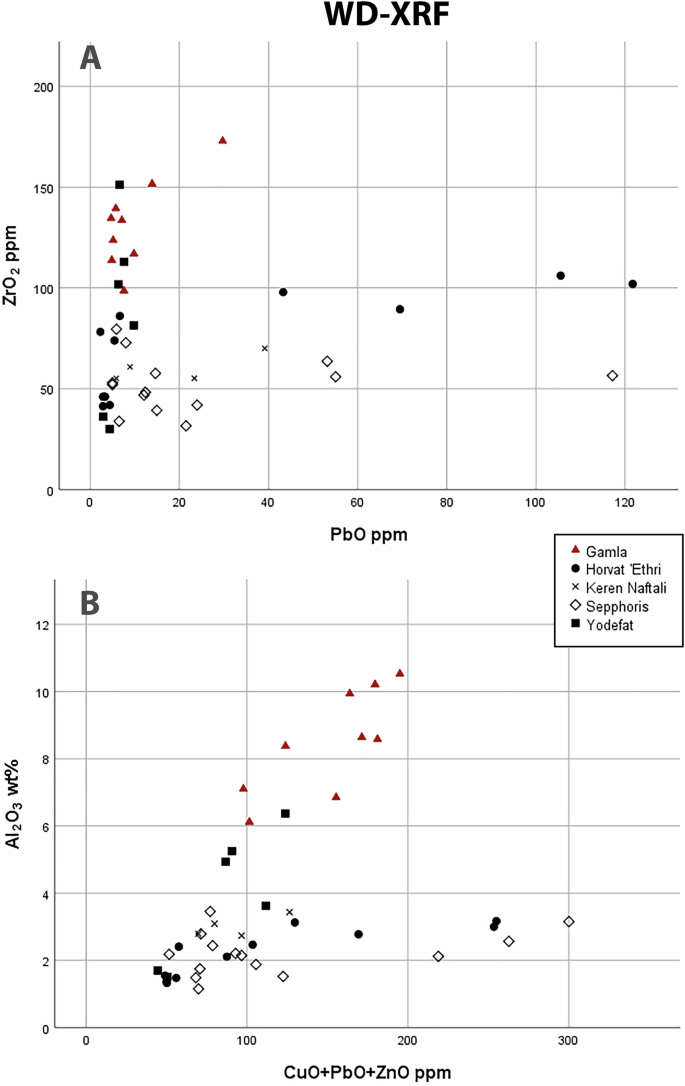

The WD-XRF-measured P2O5 values showed above-average values of over 4 wt% in two structures, Yodefat stepped pool no. 1 (YOD3) and Sepphoris SP17 (SEP12 and SEP13), both also with slightly enriched SrO at >500 ppm (Fig. 12A). For Sepphoris, higher-than-average SrO values were also measured for SP4 (SEP4, ~1800 ppm), the floor plaster of SP8 (SEP11, ~700 ppm), and another sample from SP17 (SEP14, approximately 1000 ppm). These values seem to be linked to the use or reuse of the structures as storage spaces or dumps12. The Gamla plasters in general show higher SrO, NiO, and ZrO2 values (Figs. 12A, B and 11A) than the other samples, most likely due to the background geology. Sepphoris SP17 (SEP12 and SEP13) again shows anomalous values with ZnO ≥ 150 ppm, and the ZrO2 levels of above 100 ppm from Yodefat pools 1 and 2 (YOD2, YOD5, YOD6) may also be use-derived.

A SrO ppm vs. P2O5 wt%; and B ZnO ppm vs. NiO ppm.

In his research, Shimron interpreted the increased metal content (Cu+Pb+Zn) of specific Sepphoris and Jerusalem-Ophel pools as indicating industrial use, e.g., storage of metal implements rather than use as cisterns or ritual baths17,18. We found similar enrichment (CuO+PbO+ZnO > 200 ppm; Fig. 13b) at Sepphoris, in SP4 (SEP4) and SP17 (SEP12 and SEP13), and in Horvat ‘Ethri stepped pool XIII (ETH7 and ETH8). Furthermore, we found increased Pb values of 40–120 ppm in four samples from Horvat ‘Ethri stepped pool XIII (ETH5–8), Sepphoris SP4 (SEP4) and SP17 (SEP12–13), and Keren Naftali (NAF1). No Pb was found in connection with stepped pool XIII at Horvat ‘Ethri. At Sepphoris the use of lead pipes has been attested in the area of the theater90, but not yet in connection with any stepped pools. In the literature, a similar range of increased Pb values (40–120 ppm) is linked to the use of Pb components in the drainage system91,92. This is a possible explanation in our cases as well.

A ZrO2 ppm vs. PbO ppm; and B Al2O3 wt% vs. CuO+PbO+ZnO ppm.

Analyzing these values in relation to the particular archeological contexts of the structures provides opportunities to zoom in on their particular functions. At Sepphoris, shell aggregate containing SEP4 was sampled from the topmost layer of applied plaster in SP4 and thus can be associated with its last phase of use or possible reuse. Although the excavators have not reported evidence from the structure of activities other than water storage26,29, such activities are certainly possible in light of the common repurposing of such structures at Sepphoris and other sites (e.g., Gamla L3105, L1293). Moreover, an area where food processing activities took place has been identified adjacent to the room in which SP4 was located29. In light of this context, higher values for phosphate and Sr and metal enrichment in SP4 may indicate an association with such practices in its later stages of use (first half of 2nd c. CE), either as a storage area or a dump. The plaster sample (SEP11) taken from SP8 at Sepphoris comes from a later-added floor, by means of which the structure was turned into a dry-storage installation26.

Finally, several plaster layers in SP17 show higher-than-average SrO (SEP12–14) and P2O5 (SEP12–13) values, as well as strong indications of metal enrichment (SEP12–13). This may be significant, considering that this stepped pool was part of a larger installation that included a cistern and square plastered basin. Moreover, SP17 has no apparent water connection with any of the adjacent installations; consequently, other purposes for this installation throughout its lifetime are possible. Other activities related to industrial usage, food processing, or storage would explain the considerably longer use of this structure, into the second to fourth centuries CE, compared to the other stepped pools sampled and the period of use of stepped pools as ritual baths in general9,10.

It is certainly too early to draw broader conclusions from the observed anomalies in the chemical residues, as we cannot rule out the possibility that they developed only after the use period of the stepped pools. However, the fact that these anthropogenic chemical residues occur in the plaster of stepped pools should be a warning not to draw hasty interpretive conclusions regarding their use based solely on general structural elements, i.e., plaster and steps. The anomalies in anthropogenic chemical residues from the other sites (Yodefat, Horvat ‘Ethri) may be equally related to the use or later reuse of the structures for purposes other than ritual bathing.

Most of the plasters analyzed, however, show similarly low concentration patterns of elements linked to anthropogenic enrichment (Figs. 11, 12), which is consistent with their use as water installations. It is also worth noting that we did not detect signals of pigments (enriched FeO values, hematite) in the more reddish/pinkish or other plasters in our sample set93.

Non-invasive, on-site pXRF results from plaster surfaces

While sampling for the WD-XRF and ICP-MS analysis, we also carried out pXRF measurements in the same structures to obtain data from a wider area of the plaster surface and to test whether on-site pXRF could serve as a non-invasive and cost-efficient alternative for laboratory analysis of archeological plasters. We found that in many cases the data obtained for the major and minor elements in plaster compositions showed unconvincingly low concentrations, and many of the pXRF results were also dismissed as unreliable and unusable for the trace elements.

Figure 14 shows the relationship between WD-XRF and pXRF measurements of concentrations of some of the key elements in the same layers (see data in Supplementary Data 4). It is apparent from the ratios of CaO, TiO2, and FeO (Fig. 13A–C) that there is a significant disparity between the pXRF and WD-XRF values for major and minor elements (normalized in both datasets), the pXRF resulting in an underestimating of the concentrations. The problems for the characterization of major and minor elements have to do with the inability of pXRF to provide accurate results when operated in-air on uneven and heterogeneous plaster surfaces. Surface weathering has also been found to affect Ca, Ti, and Fe values in on-site pXRF of building stones84,94. Holding the instrument by hand probably also caused instability, thereby contributing to the data quality issues. Therefore, we conclude that, at least in our case study, pXRF was unable to provide reliable data to characterize the major and minor element concentrations and to differentiate between the plaster recipes.

A CaO; B TiO2; C FeO; D SrO; E CuO; F ZrO2; G ZnO; and H PbO.

Certain heavier elements—Rb, Sr, Zr, and Ba—have been reported to be more accurately measurable via pXRF in on-site application, and even to allow the chemical fingerprinting of building materials94. Compared to the major and minor elements in our data, the correlation is slightly better for the trace elements (Z > 26, Fig. 14D–H), but for many of the REEs and trace elements of interest here the concentrations are below the pXRF detection limit. Surface weathering and contamination are clearly more dominant factors in the pXRF surface results than in the larger, homogenized samples prepared for ICP-MS and WD-XRF. For SrO and ZrO2 (Fig. 14F), the correlation is better, but the disparity grows with the values (above 1000 and 100 ppm, respectively). CuO, on the other hand, is virtually the only compound overestimated in the pXRF data (Fig. 14E). The pXRF-measured ZnO values correlate best with the WD-XRF comparanda (Fig. 14G). The only clear misfit in ZnO values (Gamla sample GAM2: pXRF result of approximately 880 vs. WD-XRF result of 120 ppm) may be associated with spot contamination of the plaster surface, e.g., urination or deposition of metal goods found to increase ZnO values82,94. For PbO (Fig. 14H), similar data patterns and the enrichment of certain plasters were detected by both XRFs, although the detection limit of the pXRF for PbO is 30 ppm. Based on the ZnO and PbO correlation between the datasets in particular, we conclude that pXRF can serve as a non-invasive tool for detecting anthropogenic trace element enrichment, and yields patterns similar to those of laboratory techniques.

Conclusions

In this article, we investigated the plaster bulk compositions, potential raw material source areas, and anthropogenic chemical residues via chemical (WD-XRF, ICP-MS, and pXRF) and microscopic (petrography, SEM-EDS) data, obtained from a total of 13 stepped pools at five Late Hellenistic–Early Roman period sites: Horvat ‘Ethri, Sepphoris, Gamla, Yodefat, and Keren Naftali.

Based on the analytical results, very similar plaster recipes were used at Horvat ‘Ethri, Sepphoris, Keren Naftali, and Yodefat. The close correlation of the plaster compositions at these four sites speaks for an equally skilled workforce and intercommunal and interregional knowledge transfer or control of the plaster industry. The fact that similar plaster recipes were used in both domestic and public contexts also supports the interpretation that the plastering was carried out by specialist workers. There are indications in written sources that technical skills were transferred through social and economic networks in the Roman world, with craftsmen moving to other cities for professional training before returning to their hometowns or villages and becoming local masters95,96. Plaster technology, like any craft, is an economic activity and therefore typically subject to elite control, although it is not known with certainty that plaster technologies were controlled on a communal level97,98,99. One can also speculate based on the unstandardized architectural design of the stepped pools that a local workforce was employed to cut the bedrock, whereas more professional workers carried out the specialist task of plastering the structures to make the surfaces waterproof.

Despite the compositional overlap between the plasters used on four of the five sites (Horvat ‘Ethri, Sepphoris, Keren Naftali, and Yodefat), it is clear from the trace and rare earth element patterns that we have five different plaster production recipes, each exploiting different sources of raw material. These results are in line with those of ref. 18, who found, based on ICP-MS/AES data, that plasters from different sites (Jerusalem-Ophel, Qumran, Jericho, and Sepphoris) were chemically distinct. Therefore, intercommunal networks of plaster materials appear not to have been in play here. The pool plasters from the fifth site (Gamla) are compositionally unrelated to those from the other sites; they represent a different plaster recipe and have different geological characteristics. The local provenance hypothesis for the plasters appears likely to be true based on the limestone samples analyzed from each site as potential raw material.

Our results also showed that variant plaster compositions were in many cases applied in different layers or parts of the stepped pools, e.g., against the bedrock, on the floor, or on the wall surface. The intrasite and intrastructural variation of the plaster recipes can also be associated with different building phases. Coutelas found that in Roman Gaul the mortar recipes used in public buildings corresponded to the construction phases of the individual structures and the city overall, and that there was “a particular lime mortar formula for each architectural use—each function requires an exact composition of materials”46.

Rare chemical residue anomalies indicate alternative use strategies for some of the stepped pools, especially Sepphoris SP17, which displayed anomalous metal concentrations, probably linked to industrial use of the structure at some point. A few pools (at Sepphoris and Yodefat) also showed enrichment with P and Sr, indicative of exposure to foodstuffs or waste. Increased Pb values on the plaster surfaces probably derive from Pb components in the drainage systems leading to the pools, even though no physical evidence of such components has yet been found. For most of the analyzed pools, however, the anthropogenic residue patterns on the plasters are not indicative of their use in non-water-related functions.

Finally, based on our on-site, non-invasive compositional data acquisition by handheld portable XRF, we can conclude that although under these measuring conditions this method was unable to discriminate between the plaster recipes, it did detect similar enrichment patterns for some of the metals on the plaster surfaces, and thus could be a useful tool for evaluating the contamination of plaster surfaces related to human activity (e.g., Zn, Pb).

Overall, the results offer novel insights into the social, cultural, and economic aspects of stepped pool construction and use in the region. The use of professional labor, with knowhow derived from intercommunal and interregional knowledge transfer, for plastering stepped pools, as well as presumably other water structures, suggests that intensive economic resources were put to use in both the public and domestic spheres. This skilled labor, building upon this knowledge, was able to exploit local and probably near-local raw materials to produce their different plasters. From the results, it appears that both at Sepphoris and at Gamla limestone material was not obtained locally at the site, but rather from more suitable areas nearby. In the case of Gamla this was likely the marly outcrop to the west, which is the closest mapped source of limestone in this basalt region. For Sepphoris the exact location of the source remains unknown. Recently, Sherman et al. traced the source of chalkstone vessels, a product type closely associated with Jewish religious and cultural practices, from archeological deposits at Sepphoris to relatively nearby quarry sites at er-Reina and Bethlehem of Galilee100. More research needs to be conducted, but we can speculate that these quarries may have been used as sources for lime plaster production as well.

Finally, evidence of anomalies in anthropogenic chemical residues in different stepped pools illustrates that more caution is needed when interpreting the function of these pools based on their general structural similarities. These similarities, together with textual evidence, have led to the consensus that these stepped pools were used primarily for Jewish purification practices. The anomalies do suggest, however, that these structures may have had a different purpose from the start (notably Sepphoris SP17) or were at some point reused as food processing areas, storage areas, or dumps. Further research on the plasters of these stepped pools is required in order to examine more thoroughly their use.

Responses