Reversibly cross-linked polymers derived from soybean oil for the consolidation of waterlogged archaeological woods

Introduction

The archaeological wood is an invaluable resource for the study of ancient culture, art, science, and technology. During prolonged underground burial, archaeological woods are corroded by acid, alkali, salts and microorganisms, leading to the severe degradation of cellulose, hemicellulose and other components in wood cells1,2. As a result, the cell structure of archaeological woods gradually become loose and their mechanical strength obviously decreases3,4. Generally, corroded archaeological woods absorb a large amount of water. Once being exposed to air, the fragile cell walls of waterlogged archaeological woods tend to collapse due to the capillary forces and the high surface tension of evaporating water5,6. Eventually, archaeological woods will shrink, deform, and even crack, failing to restore their original form and retain their precious historical information. Therefore, it is crucial to use conservation materials to dehydrate, reshape, and consolidate the waterlogged archaeological woods, thereby achieving excellent dimensional stability7,8,9,10. Because of its low cost, non-toxicity, and reversibility, polyethylene glycol (PEG) has been widely used for the conservation of waterlogged archaeological woods9,10,11. However, the introduction of PEG will soften the archaeological woods to reduce their mechanical strength12,13. Meanwhile, PEG with poor stability readily leak out of consolidated woods under high temperatures and humidity and even generate acidic substances harmful to woods over time7,8,14. Therefore, the above issues arising from PEG have significantly motivated the development of new kinds of high-performance conservation materials with high mechanical robustness and environment stability, which can improve the strength and stability of archaeological woods.

Bio-based conservation materials, derived partially or entirely from biomass, have attracted increasing attention because of their valuable properties such as low cost, sustainable resources, and safety. Compared to petroleum-based materials, biomass materials have overwhelming superiority in terms of compatibility with woods15,16. To date, scientists have developed a series of bio-based conservation materials containing animal proteins, cellulose, lignin, and their derivatives for the consolidation of waterlogged archaeological woods15,16,17,18,19,20,21. However, a large number of these bio-based conservation materials are highly hydrophilic, which leads to unsatisfactory humidity stability and largely limits their practical applications22,23. Hydrophobic biomass species such as waxes, vegetable oils, natural resins, and hydrophobic group-modified biomass can be used as conservation materials with high environment stability23,24,25,26,27. To fully and evenly penetrate into archaeological woods, the above-mentioned bio-based materials often have low molecular weight, resulting in less improvement of mechanical strength of woods. Introducing chemical cross-linking can simultaneously improve the environmental stability and mechanical robustness of bio-based conservation materials. For instance, allyl group-modified cellulose ethers and lignin can be used to consolidate archaeological woods by in situ radical polymerisation of allyl groups28,29,30. Such conservation materials cross-linked by stable covalent bonds exhibit high environmental stability and can effectively strengthen the consolidated woods. However, their reversible removability is poor as high strength and stability are often contradictory to reversible reversibility22,23. Therefore, it is still challenging to develop facile method to construct bio-based conservation materials simultaneously integrating excellent mechanical robustness, high environmental stability, and satisfactory reversible removability.

Reversibly cross-linked polymers (RCPs) can be conveniently fabricated by cross-linking polymers based on non-covalent interactions and dynamic covalent bonds31,32,33. RCPs possess well-adjustable mechanical properties and excellent recycling properties33,34,35,36,37. We believe that cross-linking low-molecular-weight biomass species with non-covalent interactions and dynamic bonds provides a practical strategy for fabricating high-performance bio-based conservation materials for archaeological woods. On one hand, low-molecular-weight biomass species can adequately permeate into the archaeological woods through material exchange and then in-situ form RCPs with high cross-linking density to enhance the mechanical strength, dimensional stability, and environmental stability of archaeological woods. On the other hand, originating from the dynamic nature of non-covalent interactions and dynamic covalent bonds, the bio-based conservation materials based on RCPs can be depolymerised into low-molecular-weight biomass species under specific conditions and efficiently removed from the archaeological woods. Although RCPs exhibit enormous advantages in the fabrication of conservation materials, bio-based reversibly cross-linked conservation materials with high mechanical robustness, excellent environmental stability, and satisfactory reversible removability have never been reported.

Epoxidized soybean oil (ESO), a low-molecular-weight (1 kDa) biomass, has the merits of wide resource, low cost, and high stability38,39. Because ESO has a tripodal structure with abundant epoxy groups, it can efficiently react with species containing amine or hydroxyl groups via ring-opening reactions to form stable cross-linking networks39,40. Therefore, ESO is an ideal candidate for the fabrication of bio-based conservation materials. Boroxines obtained by the dehydration of three boronic acids have a tripodal molecular architecture41,42, which is a perfect strong cross-linker to improve the mechanical strength and environment stability of conversation materials. Meanwhile, boroxines can break into boronic acids in the presence of alcohols, allowing the dissociation of cross-linking networks36,42. Therefore, we reasoned that the high-performance conservation materials can be conveniently fabricated by cross-linking ESO with dynamic boroxines.

In this work, we demonstrate the fabrication of bio-based conservation materials for waterlogged archaeological woods through the penetration of phenylboronic acids modified ESO in Zhangwan No.3 shipwreck samples, followed by in-situ reversibly cross-linking ESO chains with boroxines. The mechanically robust bio-based conservation materials with high cross-linking density can act as scaffold to endow the consolidated archaeological woods with excellent dimensional stability and high mechanical strength. Meanwhile, hydrophobic conservation materials can prominently improve the environmental stability of archaeological woods. More importantly, owing to the reversibility of boroxines, the conservation materials can be removed from the consolidated archaeological woods without damaging archaeological wood. This study offers new insights into the development and application of conservation materials for archaeological wood protection.

Results

Preparation and characterisation of the reversibly cross-linked ESO-B

Figure 1 demonstrates the synthesis process of phenylboronic acid-modified ESO (denoted as ESO-PBA), the consolidation of the waterlogged archaeological woods using RCP-based conservation materials formed by ESO-PBA, and the subsequent reversible removal of conservation materials. As shown in Fig. 1a, ESO-PBA was synthesised through a one-step ring-opening reaction between the epoxy groups of ESO and the amine groups of 3-aminobenzeneboronic acid. 1H NMR spectrum confirmed that ESO-PBA was successfully synthesised and the grafting ratio of PBA on ESO was ~80% (Fig. S1). To fabricate RCP films formed by ESO-PBA, the ethanol solution of ESO-PBA (0.4 g/ml) was cast onto a silicone mould and dried at 50 °C for 48 h. After the evaporation of ethanol, the phenylboronic acids of the ESO-PBA gradually dehydrated to produce boroxines and cross-link ESO chains, thereby forming RCPs (denoted as ESO-B) (Fig. 1b). ESO-B film was defect-free, transparent, and homogenous. Fourier transform infra-red (FTIR) spectra of ESO, ESO-B, and PBA are shown in Fig. S2. The characteristic peak at 841 cm−1 in the FTIR spectrum of ESO was attributed to epoxy groups of ESO, which almost disappeared in the FTIR spectrum of ESO-B. Meanwhile, the characteristic peak of -OH at 3546 cm−1 and the N-H at 3470 and 3389 cm−1 appeared in the FTIR spectrum of ESO-B, indicating the successful grafting of PBA on ESO39. In addition, the BO-H stretching peak at 3320 cm–1 for PBA disappeared and a new characteristic peak of boroxines appeared at 710 cm−1 in the FTIR spectrum of ESO-B43. Therefore, the ESO-B bulk materials were mainly formed by boroxine-cross-linked ESO chains.

a Synthesis route of ESO-PBA. b Schematic of the formation of ESO-B from ESO-PBA. Inset: photograph of the ESO-B film. The scale bar is 1 cm. c Schematic illustration of the consolidation of waterlogged archaeological wood with reversibly cross-linked ESO-B conservation materials.

As shown in Fig. S3, the ESO-B film was highly transparent in the visible region, with a transmittance of ∼95.6% at 550 nm. Mechanical strength was essential for the conservation effect of conservation materials. Therefore, the tensile and compression test of the ESO-B films were conducted at room temperature and 33% RH. As shown in Fig. S4, the ESO-B film exhibited a high tensile strength of ~51.4 MPa. The high mechanical robustness of the ESO-B film mainly originated from the stable and high-density cross-linking of boroxines. As a comparison, PBA-modified ESO with lower grafting ratio of ~40% (denoted as ESO-B40%) was also synthesised and fabricated into films based on the same procedure to ESO-B (grafting ratio of PBA to ESO being ~80%). As shown in Fig. S4, the ESO-B40% film possessed a tensile strength of only ~14.6 MPa. Because of lower cross-linking density, the tensile strength of the ESO-B40% film was obviously lower than that of the ESO-B film. Furthermore, the mechanical properties of widely used PEG conservation materials were also evaluated. PEG films were fabricated by casting the aqueous solution of PEG with the molecular weight of 1500 into a silicone mould, followed being dried at 50 °C for 48 h. Unfortunately, PEG films cannot be stretched because they were easily broken by the fixture of the testing machine. Then the compression tests of PEG and ESO-B bulk materials with thickness of ~5 mm were conducted at room temperature. As shown in Fig. S5, the compression strength of the PEG bulk material was only ~4.9 MPa at 70% strain. By sharp contrast, the ESO-B bulk material possessed a compression strength of ~94.7 MPa at 70% strain, which was 19 times higher than that of PEG. Above results indicated that the ESO-B exhibited superior mechanical properties to those of PEG. Therefore, the transparent and mechanically robust ESO-B was an ideal candidate for high-performance conservation materials to endow waterlogged archaeological woods with high strength and excellent dimensional stability.

Consolidation of waterlogged wood samples by ESO-B

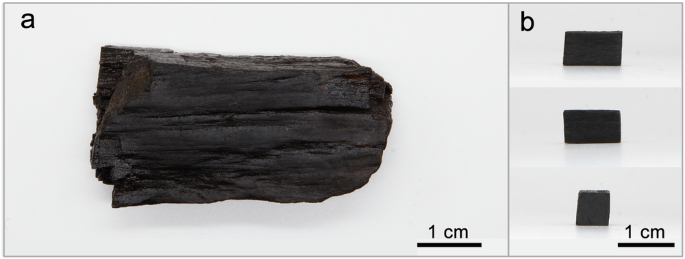

The waterlogged archaeological woods obtained from the Zhangwan No.3 shipwreck were cut into blocks with ~10 mm (longitudinal) × ~5 mm (tangential) × ~5 mm (radial) in size for the consolidation experiments (Fig. 2). The wood samples were moderately degraded and had a maximum water content (MWC) of ~299.9%. As shown in Fig. S6, wood samples were firstly immersed in ethanol for 1 week to replace the water inside them prior to consolidation. Subsequently, wood samples were immersed into the ESO-PBA ethanol solution (0.4 g/ml) at room temperature for 1 week, achieving the effective penetration and filling of low-molecular-weight ESO-PBA in the wood samples (Fig. 1c). The weight percent gain (WPG) of consolidated wood samples was measured to determine the endpoint of immersion time. The WPG of consolidated wood samples was ~85.2% and no longer increased after 1 week-immersion, demonstrating that the basically complete permeation of ESO-PBA (Fig. S7). The ESO-PBA-filled wood samples were fully dried at ~58% RH for 1 week, during which the PBA groups of the ESO-PBA gradually dehydrated and produce boroxines to in-situ form cross-linked ESO chains. The in-situ formation of ESO-B reversibly cross-linked conservation materials in the consolidated wood samples (denoted as W-ESO-B) was confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy. As shown in Fig. 3a, the characteristic absorption peaks at 3546, 1742, 1600/1579, and 710 cm−1 in the FTIR spectrum of the ESO-B film were assigned to -OH, C=O, C=C and boroxines groups, respectively. These characteristic peaks also existed in the FTIR spectrum of the W-ESO-B sample, indicating that ESO-PBA successfully penetrated into the wood and in-situ formed boroxine-cross-linked ESO-B conservation materials. The characteristic absorption peaks at 3434, 1735, and 1508 cm-1 in the FTIR spectrum of un-consolidated archaeological wood sample (denoted as WOOD) were attributed to stretching vibration of -OH groups of cellulose components, C=O groups of hemicellulose components and C=C stretching of aromatic skeletal of lignin, respectively (Fig. 3a)44. Meanwhile, the FTIR spectrum of the W-ESO-B sample still contained characteristic peaks of WOOD sample. This demonstrated that the penetration of ESO-PBA and in-situ formation of ESO-B did not damage the archaeological wood.

a The overall appearance of the waterlogged archaeological wood. b Three views of a wood sample with the dimensions of ~10 mm (longitudinal) × ~5 mm (tangential) × ~5 mm (radial).

a FTIR spectra of the ESO-B film, WOOD sample, and W-ESO-B sample in the range of 3750-520 cm−1. b–g Cross-sectional SEM images of the WOOD b, c and W-ESO-B d, e samples. EDS elemental mapping images for B (f) and N (g) of the W-ESO-B sample.

The internal structures of the air-dried WOOD and W-ESO-B samples were further investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As shown in Fig. 3b, c, air-dried WOOD dramatically shrunk to compress cell lumens and its cell walls became thin, porous and distorted, originating from losing of water support and degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose. By sharp contrast, the internal structure of the W-ESO-B sample displayed more regular without apparent shrinkage and distortion (Fig. 3d, e). The W-ESO-B sample had smoother and thicker cell walls with fewer cavities compared with the air-dried WOOD sample. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping image of the W-ESO-B sample confirmed that the in-situ formed ESO-B RCPs homogeneously distributed in the cell walls (Fig. 3f, g). Meanwhile, ESO-B did not fill into the cell lumens of the wood sample, meaning that the original structure of the wood was largely preserved. The remaining cell lumens were beneficial for refilling advanced consolidation materials in the future to further consolidate the woods. Therefore, the results of FTIR spectra and SEM images firmly proved the successful formation of ESO-B conservation materials in the archaeological wood sample. Moreover, the construction of the ESO-B conservation materials only required penetration and in-situ dynamically cross-linking at room temperature.

Dimensional stability of consolidated wood samples

Dimensional stability of consolidated archaeological woods is the most basic parameter to evaluate the consolidation effect of conservation materials. Therefore, the volumetric shrinkage efficiency (SE) and anti-shrinkage efficiency (ASE) of the consolidated archaeological wood samples were examined to investigate their dimensional stability (Fig. 4a). Meanwhile, the digital images of wood samples before and after consolidation were also recorded (Fig. 4b–e). The digital image in Fig. 4b showed that the WOOD sample severely shrunk and deformed with the volumetric shrinkage efficiency (S0) being ~42.6% after fully drying in the air. As shown in Fig. 4c, after being consolidated with ESO-B, the fully dried W-ESO-B sample has almost no shrinkage and deformation in comparison with original waterlogged archaeological wood. Moreover, the SE of W-ESO-B sample dramatically reduced to ~2.9% and its ASE was as high as ~93.2%, demonstrating that the in-situ construction of ESO-B can significantly improve the dimensional stability of waterlogged archaeological wood (Fig. 4a). As shown in Fig. 4d, the shrinkage and deformation of wood sample consolidated with pure ESO (denoted as W-ESO) were more obvious than those of the W-ESO-B sample. The SE and ASE of the W-ESO sample were ~19.7% and ~53.8%, respectively, confirming that the W-ESO sample had inferior dimensional stability to the W-ESO-B sample. Therefore, the high cross-linking density of ESO-B played an important role in improving dimensional stability of consolidated wood samples. In addition, the wood sample consolidated with PEG (denoted as W-PEG) also had a shrinkage compared with original wood sample (Fig. 4e). The SE of the W-PEG sample was much larger than that of the W-ESO-B sample and its ASE was smaller (Fig. 4a).

a SE and ASE of the W-ESO-B, W-ESO and W-PEG samples. b Digital images of two views of original waterlogged archaeological wood sample and fully dried WOOD sample. Digital images of two views of original waterlogged archaeological wood samples and the corresponding consolidated W-ESO-B (c), W-ESO (d), and W-PEG (e) samples. The scale bar is 0.5 cm.

According to SEM images of the WOOD and W-ESO-B samples (Fig. 3b–e), we considered that the excellent consolidation of archaeological woods by ESO-B can be explained as follows: When immersing the archaeological wood sample in the ESO-PBA solution, low-molecular-weight ESO-PBA can rapidly penetrate into the cell walls of wood sample and sufficiently fill into their cavity. Because the PBA can simply form boroxines through dehydration, ESO-PBA chains in the cell walls can in-situ form boroxine-cross-linked ESO-B conservation materials after the consolidated wood sample is fully dried at room temperature. The stable cross-linking networks can provide ESO-B with high mechanical robustness and the oxygen-containing groups of ESO-B can form hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl groups of cellulose and lignin in the cell walls. Therefore, the in-situ formed ESO-B with stable cross-linking networks can serve as scaffold to support skeleton of the wood structure and prevent the shrinkage and deformation of the consolidated wood samples during ethanol evaporation, thereby endowing them with excellent dimensional stability. As shown in Fig. S8, the PEG could also penetrate into the cell walls of the wood sample to obtain the thicker cell walls with fewer cavities compared with the WOOD sample. Filled PEG in the cell walls supported the skeleton of the wood structure to decrease its shrinkage and deformation during dehydration, thereby making the internal structure of the W-PEG sample more regular than the WOOD sample. However, the distortion structure of W-PEG sample was still obvious compared with the W-ESO-B sample. The WPG of the W-PEG sample was ~74.6% and slightly lower than that of the W-ESO-B sample (~85.2%), indicating that ESO-PBA had superior permeability to that of PEG with the molecular weight of 1500. Due to inferior permeability and lack of three-dimensional cross-linking networks, linear PEG showed limitation in the improvement of dimensional stability compared with ESO-B. To further demonstrate the excellent penetration of the ESO-PBA conservation materials, the Zhangwan No.3 shipwreck wood sample with a larger size (~25 mm (longitudinal) × ~25 mm (tangential) × ~7 mm (radial)) was also consolidated with ESO-B (Fig. S9). The SE and ASE of the large W-ESO-B sample were ~1.5% and ~96.5%, respectively, showing equally excellent dimensional stability to that of small consolidated wood samples. In addition, to preserve the original appearance of archaeological woods, the conservation materials should minimise the influence on the colour of archaeological woods. Total colour change (ΔE*) of W-ESO-B, W-ESO, and W-PEG samples were measured to evaluate the colour change of wood samples before and after the consolidation. As shown in Fig. S10, ΔE* of W-ESO-B and W-PEG samples were 8.6 ± 1.5 and 6.7 ± 1.3, respectively. These values indicated that both of the W-ESO-B and W-PEG samples exhibited slight colour changes compared with WOOD samples. However, the W-ESO sample had dramatic colour changes with large ΔE* of 11.1 ± 1.8. Based on the above results, because the W-ESO-B samples displayed excellent consolidation effect with superior dimensional stability to PEG-consolidated samples, ESO-B was highly expected to be used as high-performance conservation materials for waterlogged archaeological woods.

Mechanical properties and environmental stability of the consolidated wood samples

Generally, cellulose provides the longitudinal strength and stiffness of archaeological woods. Degradation of cellulose in waterlogged archaeological woods inevitably leads to serious deterioration in their mechanical strength44,45. Therefore, it is essential to improve the mechanical properties of waterlogged archaeological woods with the assistance of conservation materials. As shown in Fig. 5a, b, the mechanical properties of the WOOD, W-ESO-B, and W-PEG samples were evaluated by compression tests at 33% RH and 25 °C. The WOOD sample from Zhangwan No. 3 shipwreck exhibited a low compression strength of ~3.4 MPa and an elastic modulus of ~65.9 MPa. After being consolidated with PEG, the compression strength and elastic modulus of the W-PEG sample decreased to ~2.1 MPa and ~42.6 MPa, respectively. Previous studies have shown that consolidation with PEG can reduce the cell wall matrix stiffness of wood through interaction with the amorphous parts of the wood12,13. By sharp contrast, the W-ESO-B sample exhibited a high compression strength of ~17.9 MPa and a high elastic modulus of ~343.7 MPa, which were 5.3- and 5.2- times higher than those of WOOD samples (Fig. 5a, b). Significantly improved mechanical properties of the W-ESO-B samples mainly originated from high mechanical robustness of ESO-B conservation materials. Highly cross-linked ESO-B conservation materials with a high compression strength of ~94.7 MPa can serve as sturdy scaffold to support skeleton of the wood structure and enhance the compression strength of the archaeological wood.

a Compression curves of the WOOD, W-ESO-B and W-PEG samples. b Compression stress and elastic modulus of the WOOD, W-ESO-B and W-PEG samples. c EMC of the WOOD, W-ESO-B, and W-PEG samples after being placed in the environments with 33%, 58%, 84%, and 100% RH. d Time-dependent water contact angles of the WOOD, W-ESO-B, and W-PEG samples. e DSC curves of the WOOD, W-ESO-B, and W-PEG samples. f TGA and DTG curves of the WOOD, W-ESO-B, and W-PEG samples.

The environmental stability (e.g. humidity and thermal stability) of conservation materials is essential for long-term preservation of archaeological woods. To investigate their humidity stability, the WOOD, W-ESO-B, and W-PEG samples were exposed to the environment with 33%, 58%, 84%, and 100% RH for 10 days and their weight changes were recorded. As shown in Fig. 5c, all wood samples exhibited an increase in equilibrium moisture content (EMC) with increased environment humidity. Although being placed at relatively dry environment of 33% RH, the WOOD sample also absorbed water to exhibit the EMC of ~6.6%. Meanwhile, the highest EMC of the WOOD sample can reach up to ~34.7% at 100% RH. Water contact angle on the WOOD sample was determined to be 70.9°, demonstrating the hydrophilic nature of WOOD sample (Fig. S11a). Moreover, time-dependent contact angle measurement showed that water droplet on WOOD sample was quickly absorbed inside and the water contact angle on it decreased to 0° within 4 s (Fig. 5d and Fig. S11a). Highly hydrophilic hemicellulose and cellulose and porous structure of the WOOD sample made it easily absorb moisture and exhibit unsatisfactory humidity stability. As shown in Fig. 5c, the W-ESO-B sample exhibited the lowest EMC at different RHs among all wood samples. Even at 100% RH, the EMC of W-ESO-B sample was only ~12.6%, which was ~2.8 times less than that of the WOOD sample. Therefore, after being consolidated with ESO-B, the humidity stability of the W-ESO-B sample was largely improved. Water contact angle on the W-ESO-B sample was 132.0°, which indicated its hydrophobic surface (Fig. S11b). More importantly, the water droplet on the W-ESO-B sample was barely absorbed into it and its water contact angle remained nearly constant within 120 s (Fig. 5d and Fig. S11b). Fig. S12 showed EMC of the ESO-B bulk material at the environments with different RHs. Due to hydrophobic ESO chains and cross-linked structure, pure ESO-B bulk material exhibited excellent humidity stability and its EMC only slightly increased with increasing RH of environment. Therefore, we considered that excellent humidity stability of W-ESO-B sample originated from the in-situ formed ESO-B conservation materials, which can act as hydrophobic and dense barrier layers on the surface and inside of the wood to effectively prevent the penetration of moisture even water droplet. As control experiment, the humidity stability of the W-PEG sample was also investigated (Fig. 5c). The W-PEG sample exhibited the largest EMC among all wood samples at different RHs except for 33%RH. As shown in Fig. S12, the trend of EMC of the W-PEG sample was completely consistent with pure PEG bulk material. Therefore, the introduction of hydrophilic PEG was the main reason for increasing EMC of the W-PEG sample. Meanwhile, the initial water contact angle of W-PEG sample was only 25.8°, which was much smaller than that of the WOOD sample (Fig. S11c). Water droplet on the W-PEG sample was quickly absorbed inside and the water contact angle on it decreased to 0° within 40 s, confirming the poorest humidity stability of W-PEG samples (Fig. 5d and Fig. S11c). Therefore, the in-situ construction of hydrophobic and highly cross-linked ESO-B conservation materials endowed the W-ESO-B sample with excellent humidity stability, which significantly surpassed the WOOD and W-PEG samples.

Furthermore, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was employed to investigate the thermal stability of the WOOD, W-ESO-B, and W-PEG samples. As shown in Fig. 5e, the WOOD sample exhibited no phase transformation in the range from −40 to 140 °C. The DSC curve of W-ESO-B sample was similar to the WOOD sample, meaning that ESO-B conservation materials inside did not undergo glass transition and melting. The above results were also confirmed by the DSC curve of pure ESO-B film (Fig. S13). DSC curve of the W-PEG sample showed a melting peak at ~51.0 °C (Fig. 5e). This melting peak was consistent with pure PEG and corresponded to the melting temperature (Tm) of the crystallised PEG (Fig. S13). The PEG conservation materials easily melted at high temperatures, thereby significantly decreasing the thermal stability of the W-PEG sample. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was also measured to evaluate the thermal stability of the WOOD, W-ESO-B, and W-PEG samples (Fig. 5f). The first-order differentiation curves for TGA (DTG) of the WOOD sample indicated that its maximum decomposition temperature (between 150 and 700 °C) was ~350.9 °C. After being consolidated with ESO-B and PEG, the maximum decomposition temperature of the W-ESO-B and W-PEG samples increased to ~366.5 and ~387.6 °C, respectively, meaning that the thermal stability of W-ESO-B and W-PEG samples were improved. In addition, two peaks of the W-ESO-B sample in DTG curve originated from ESO-B (Fig. S14). Therefore, ESO-B polymers with high mechanical robustness and stability were very suitable for being used as high-performance conservation materials to improve the dimensional stability, mechanical properties, humidity stability, and thermal stability of archaeological woods.

Reversible removability of the ESO-B conservation materials

Reversibility is indispensable for conservation materials in practical usage, because it can offer the opportunity to retreat the archaeological woods. However, many reported high-performance conservation materials can only achieve the retreatability, but cannot display reversibility7,22. As shown in Fig. 6a, the reversibility of the ESO-B film was first examined by cutting it into small pieces and dissolving them in ethanol. Because ethanol can break the boroxine cross-linkers to generate boronic acids, the ESO-B can depolymerise into ESO-PBA and dissolve in ethanol at room temperature. The ethanol solution of ESO-PBA was then poured into a silicone mould to regenerate transparent ESO-B film by reforming boroxines after ethanol evaporation (Fig. 6a). Therefore, pure ESO-B film exhibited excellent reversibility under mild conditions. According to above results, the W-ESO-B samples were immersed in ethanol to investigate the reversibility of the ESO-B conservation materials in consolidated sample. After being immersed in ethanol at 70 °C for 2 and 4 weeks, the corresponding W-ESO-B samples were completely dried at room temperature and denoted as W-R2 and W-R4. Compared with FTIR spectrum of the W-ESO-B sample, the main characteristic absorption peaks of ESO-B at 1742, 1600/1579 and 710 cm−1 in the W-R2 sample obviously decreased, demonstrating that a large number of ESO-B conservation materials were removed from consolidated archaeological woods (Fig. 6b). The FTIR spectra further demonstrated that extending the immersion times in ethanol to 4 weeks can basically remove ESO-B conservation materials from the W-R4 sample. Moreover, the characteristic peaks of archaeological wood in FTIR spectra of the W-R4 samples were identical to that of the un-consolidated WOOD sample, indicating that the removal process of ESO-B did not change the composition of archaeological woods. As shown in Fig. 6c, compared with the W-ESO-B sample, the W-R4 sample had a shrinkage, which was caused by removing of ESO-B conservation materials. During the immersion, ethanol can effectively penetrate into the W-ESO-B sample to break the cross-linked structure of in-situ formed ESO-B conservation material and depolymerise it into soluble ESO-PBA. Because the amount of ESO-B in the W-ESO-B sample was much less than solvent, the re-generated ESO-PBA can be easily extracted from the wood. Therefore, integrating excellent dimensional stability, mechanical robustness, environmental stability, and satisfactory reversible removability, in-situ formed reversibly cross-linked ESO-B conservation materials show great potential to replace traditional conservation materials for waterlogged archaeological woods.

a Digital images of recycling of the ESO-B film with the assistance of ethanol. b FTIR spectra of the WOOD, W-ESO-B, W-R2, and W-R4 samples in the range of 3750-520 cm−1. c Digital images of two views of the W-R4 sample after being fully dried. The scale bar is 0.5 cm.

Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated the fabrication of bio-based reversibly cross-linked conservation materials (ESO-B) for waterlogged archaeological woods. ESO-B exhibited high transparency, superior mechanical properties, and environmental stability compared to conventional conservation materials like PEG, making it highly effective for the consolidation of waterlogged archaeological woods. The ESO-B films demonstrated excellent tensile strength of ~51.4 MPa and compression strength of ~94.7 MPa, which far outperformed PEG-based materials. Then, the ESO-B consolidated waterlogged archaeological woods which integrated high mechanical robustness, excellent environmental stability and satisfactory reversibility were fabricated by the penetration and filling of low-molecular-weight ESO-PBA in the Zhangwan No.3 shipwreck wood samples and then in-situ dynamic cross-linking ESO with boroxines at room temperature. The SEM and FTIR analyses confirmed that the cross-linked ESO-B did not damage the original wood structure, ensuring preservation of its integrity. The high density of cross-linking structure endowed ESO-B conservation materials with high mechanical robustness and excellent environmental stability. Therefore, the ESO-B in-situ formed on the cell walls can act as scaffold to significantly improve the dimensional stability and mechanical properties of the W-ESO-B wood. The SE of the W-ESO-B wood was only ~2.9% and its ASE was as high as ~93.2%. Meanwhile, the W-ESO-B wood possessed high compression strength and elastic modulus of ~17.9 and ~343.7 MPa, respectively, which are significantly higher than those of unconsolidated wood. Even being exposed to highly humid environment (100% RH), the W-ESO-B wood maintained a low EMC of ~12.6%, exhibiting excellent humidity stability. Dimensional stability, mechanical properties, and environmental stability of the W-ESO-B woods are much superior to those of un-consolidated and conventional PEG-consolidated woods. More importantly, the reversible cross-linking structures of ESO-B conservation materials enabled them be reversibly removed from the W-ESO-B wood through simply rinsing wood sample in ethanol. Reversible removability of the ESO-B conservation materials allows the retreatment of archaeological woods, which are important for their practical usage. The ESO-B conservation materials composed of environmentally friendly and cost-effective raw materials can make full use of biomass resources and are suitable for mass production. We believe that this study presents a new method for the fabrication of high-performance bio-based conservation materials with satisfactory reversible removability to significantly improve the dimensional stability, mechanical properties and environmental stability of archaeological woods.

Methods

Materials

ESO (Mw ≈ 1000 g/mol) was purchased from Aladdin. 3-Aminobenzeneboronic acid was purchased from Innochem Technology Co., Ltd. Methanol-d4 was purchased from Energy Chemica. PEG (Mw≈1500 g/mol) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. MgCl2, NaBr, and KCl were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Ethanol and tetrahydrofuran (THF) were purchased from Beijing Chemical Reagents Company. All chemicals were used without further purification.

Preparation and physical properties of wood samples

Zhangwan shipwreck site is located in the southeast of Zhangwan Village in Tianjin, China, at the turning point of the Beiyun River channel. The Tianjin Cultural Heritage Protection Center excavated the 550-square-metre site and found three wooden shipwrecks from April to June in 2012. According to the sedimentary layer and the age of the unearthed artifacts, the ships were dated to the late Yuan and early Ming dynasties. The bow and stern of Zhangwan No. 3 shipwreck were totally destroyed, but its 11.8-metre-long and 2.8-metre-wide hull remained intact. Zhangwan No. 3 shipwreck is currently preserved in Tianjin Cultural Heritage Protection Center. The waterlogged archaeological woods used in this work were obtained from the bottom plate of Zhangwan No. 3 shipwreck (Fig. 2a). The wooden stuffs of Zhangwan No. 3 shipwreck were identified as poplar (populus sp.). For the consolidation experiments of the waterlogged archaeological woods, wood samples from Zhangwan No. 3 shipwreck were cut into 40 blocks with ~10 mm (longitudinal) × ~5 mm (tangential) × ~5 mm (radial) in size (Fig. 2b).

The physical properties of original waterlogged archaeological woods were evaluated by measuring their MWC and S0. The MWC of original waterlogged archaeological wood samples was calculated using the following equation:

where M1 (g) was the mass of waterlogged archaeological wood samples and M0 (g) was the mass of archaeological wood samples after being fully dried in oven.

The S0 of original waterlogged archaeological wood samples was calculated using the following equation:

where V0 (mm3) was the volume of waterlogged archaeological wood samples and V1 (mm3) was the volume of archaeological wood samples after being fully dried in air.

Synthesis of ESO-PBA

The ESO-PBA was synthesised through a one-step ring-opening reaction between the epoxy groups of ESO and the amine groups of 3-aminobenzeneboronic acid (Fig. 1a). ESO (10.00 g) was dissolved in 100 mL of THF at room temperature, followed by the addition of 3-aminobenzeneboronic acid (5.48 g) to the solution. The reaction was continuously stirred at room temperature for 12 h. After removing the unreacted suspended 3-aminobenzeneboronic acid through filtration, the resulting solution was dried at 50 °C for 24 h to yield ESO-PBA (~96%). The freshly obtained ESO-PBA (25 mg) was dissolved in methanol-d4 (0.7 mL) for 1H NMR test (Fig. S1). 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d4, δ): 7.55–6.51 (m), 5.26 (s), 4.34 (d), 4.16 (d), 4.12–3.40 (m), 2.43-2.15 (m), 1.74-1.06 (m), 1.00-0.75 (m). The molecular weight of ESO-PBA was calculated to be ~1474 g/mol. The grafting ratio of PBA to ESO was calculated based on 1H NMR, being ~80%. Additionally, ESO-PBA with the grafting ratio of PBA to ESO being ~40% was also prepared by the same procedure to the above one except for replacing 5.48 g of 3-aminobenzeneboronic acid with 2.74 g (denoted as ESO-PBA40%).

The consolidation of wood samples

The consolidation of wood samples with ESO-B: Firstly, the wood samples were immersed in ethanol to replace the water in them. The ethanol was changed every day and the density of the immersion solution was monitored. After 1 week, the density of the immersion solution approached to that of pure ethanol, confirming that the water in the wood samples was almost replaced by ethanol. Then, ESO-PBA (1 g) was dissolved in ethanol (2.5 mL) to prepare the consolidation solution of ESO-PBA with the concentration of 0.4 g/ml. The wood samples were immersed in the ESO-PBA ethanol solution in sealed flasks for 1 week. The volume ratio of the wood samples and the ESO-PBA ethanol solution was 1:10. Then the treated wood samples were dried at the ambient environment (relative humidity (RH) of ~58% and 25 °C) for 1 week, until the weight of consolidated wood samples no longer decreased. As the ethanol fully evaporated at room temperature, the PBA groups of ESO-PBA gradually dehydrated and trimerized into boroxines, facilitating the in-situ formation of reversibly cross-link ESO in wood samples. The consolidation process of wood sample with larger size (~25 mm (longitudinal) × ~25 mm (tangential) × ~7 mm (radial)) was the same as the above process except for extending the immersion time in ESO-PBA solution to 2 weeks.

The consolidation of wood samples with ESO: The consolidation process of wood samples using ESO was the same as the procedure of those using ESO-PBA except for replacing ESO-PBA with ESO.

The consolidation of wood samples with PEG: Due to the closest molecular weight to ESO-PBA, PEG with molecular weight of 1500 g/mol was selected as control conservation materials to eliminate the influence of molecular weight on the consolidation effect. PEG (1 g) was dissolved in aqueous solution (2.5 mL) to prepare the consolidation solution of PEG with the concentration of 0.4 g/ml. The wood samples were immersed in the PEG aqueous solution in sealed flasks for 1 week. The volume ratio of the wood samples and the PEG solution was 1:10. After treatment with PEG, wood samples were dried at ~58% RH and 25 °C for 1 week, until the weight of consolidated wood samples no longer decreased.

The WPG of consolidated wood samples

The WPG was measured to determine the endpoint of soaking time. The WPG of consolidated wood samples was calculated using the following equation:

Where W0 is the weight of dried wood sample without consolidation, and W1 is the weight of consolidated wood samples after drying at the ambient environment (~58% RH and 25 °C). Due to the fact that waterlogged wood samples cannot be dried before treatment (it would cause its shrinkage and cracking and the sample would be useless for further experiments), the dried weight of the wood samples without consolidation was calculated based on the maximum water content or maximum ethanol content in similar samples.

Dimensional stability of consolidated wood samples

The dimensional stability of consolidated wood samples was evaluated by measuring the SE and ASE.

The SE of consolidated wood samples was calculated using the following equation:

where V0 (mm3) is the initial volume of waterlogged wood samples, and V1 (mm3) is the volume of consolidated wood samples after being fully dried at the ambient environment (~58% RH and 25 °C).

The ASE of consolidated wood samples was calculated using the following equation:

where S0 (%) is the volumetric shrinkage efficiency of air-dried wood sample without treatment, and S (%) is the volumetric shrinkage of consolidated wood samples.

Colour changes of consolidated wood samples

Colour changes of consolidated wood samples were examined using a colorimeter (LS173, Linshang Technology, China). The value of total colour change (ΔE*) which reflected the colour changes of the woods was defined as:

L*, a*, and b* which were tested by the colorimeter represented the lightness of the colour, the colour components from green to red, and the colour components from blue to yellow, respectively. ΔL*, Δa*, and Δb* values were the differences between corresponding L*, a*, and b* values of the original wood samples and treated samples.

Humidity stability of consolidated wood samples

The EMC of untreated and treated wood samples were determined to evaluate their humidity stability. Firstly, the wood samples were placed at the humid environments of 33%, 58%, 84% and 100% RH for 10 days, respectively. Then, the mass changes of the wood samples were measured to calculate their EMC. The EMC of the wood samples was calculated using the following equation:

where M0 is the mass of oven-dried wood samples, and M1 is the mass of wood samples after being placed in humid environments with different RHs.

Mechanical properties of conservation materials and consolidated wood samples

All tensile and compressive tests were carried out on an Instron 5944 testing machine (AG-I 2kN) with a stretching speed of 50 mm/min and a compressive speed of 2 mm/min at the ambient environment (~33% RH and ~25 °C). For tensile tests, the films were prepared with 12.5 mm (length) × 2 mm (width) × 0.5 mm (thickness) in size. For compression tests, the bulk polymer materials were prepared with 4 mm (length) × 4 mm (width) × 5 mm (thickness) in size, and wood samples were cut into blocks with ~5 mm (longitudinal) × ~5 mm (tangential) × ~5 mm (radial) in size. All the wood samples were tested along the longitudinal direction for compression tests.

Reversibility of ESO-B conservation materials

The W-ESO-B wood samples were immersed in ethanol and heated at 70 °C to remove ESO-B from W-ESO-B samples by causing the depolymerisation of ESO-B into low-molecular-weight ESO-PBA. The volume ratio of the wood samples and ethanol solution was 1:20. After being rinsed in ethanol for 2 and 4 weeks, the wood samples were dried in an oven of 60 °C for 2 days.

Instruments

FTIR spectra were measured using a Bruker VERTEX 80 V FTIR spectrometer. ESO and ESO-B films for FTIR spectroscopy were tested in transmission mode through depositing them on KBr slices and silicon wafers, respectively. All of the wood samples used for FTIR spectroscopy were obtained from the centre of them and grinded to powders, followed by being blended with KBr and tested in transmission mode. 1H NMR spectra were recorded using a 500-MHz Bruker AVANCE III instrument. SEM images measured on the transections of wood samples were obtained by a Zesiss Sigma300 scanning electron microscope under vacuum. The EDS measurements were conducted on an Oxford ultimmax instrument attached to the Zeiss Sigma300 SEM. All wood samples for SEM were obtained from the centre of them and coated with a thin layer of gold (2–3 nm) before SEM imaging. The digital images were captured by a Canon 5D MarkIII camera. TGA measurements were performed on a 500 thermogravimetric analysis (TA Instruments, USA) with a heating rate of 10 °C/min under a N2 atmosphere. DSC measurements were performed on a TA Instruments Q200 differential scanning calorimeter under the nitrogen flow of 50 mL/min. UV–vis transmission spectra were recorded with a Shimadzu UV-2550 spectrophotometer. Water contact angles of wood samples were measured using a Drop Shape Analysis System DSA10-MK2 (Kruess, Germany) at room temperature with a 4 μL droplet as the indicator.

Responses