Unraveling the ink composition of ancient palm leaf manuscript from Tibet: A multi-analytical study

Introduction

Palm leaf manuscripts are considered the prevailing writing and painting support in South and Southeast Asia before the invention of paper, which holds significant importance for the transmission of Buddhist Scriptures, literature, history and medicine, etc.1. Currently, nearly 30,000 pieces of ancient palm-leaf manuscripts are still preserved in Tibetan monasteries. These palm-leaf manuscripts originated from ancient India, encompassing nearly ten different ancient scripts from the South Asian subcontinent. Most palm-leaf manuscripts predominantly date from the 11th to the 14th centuries CE, with few originating from before the 11th century CE, which were written with ink directly on both sides using tools such as reed. It can be summarized that the inks used in ancient Indian manuscripts were often made from soot, lipids, and various adhesive substances. However, the specific composition of ink still requires further research. Since the ink is crucial for revealing the text content, its study and preservation require greater attention.

Several studies have been carried out on the ink of palm-leaf manuscripts, mainly focusing on the processing of preparing ink in different regions2,3,4,5. Based on the above literature, it can be found that the preparation of ink exhibits subtle variations influenced by its leaf species, the availability of local materials, regional customs, and religious beliefs, thereby complicating the study of ink composition. Given that the ancient palm-leaf manuscript is extremely precious and difficult to obtain, there are few researches about the composition of ink through scientific analysis methods, that have not comprehensively revealed the type of ink and adhesive in much detail. In the previous study, the ink of the palm-leaf manuscript was concluded as lampblack mainly by SEM–EDX analysis, suggesting it was produced by burning resinous or oily materials in a restricted-oxygen environment beneath a funnel6,7. Furthermore, Raman spectroscopy and infrared reflectography (IRR) confirmed the ink’s carbon-based composition8. Some adhesives, such as polysaccharides and pectin were found by FTIR and GC–MS9,10. However, it was thus found that there is limited literature on the study of ink composition, and no systematic research has yet been reported on the composition of ink samples from the Tibetan region, additional evidence necessitates a more complementary and integrative analysis approach.

The composition and processes of ink in palm-leaf manuscripts are not fully understood currently. To address this research gap, this study focuses on identifying ink samples of palm-leaf manuscripts, with the aim of scientifically analyzing the types of ink and adhesive. The historical ink samples were collected from Tibet, which houses the largest collection of palm-leaf manuscripts in China. Due to the limited number of ink samples and the potential limitations of certain specific technologies, multi-analytical techniques, encompassing both non-destructive and destructive approaches as well as structural and compositional analyses, were adopted to perform a comprehensive investigation of the ink’s original composition: the digital microscope, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were used for observing the morphology and primary particle size of ink. Energy dispersive spectrometry (EDS) was applied to obtain the element of the ink sample and Raman spectroscopy was conducted to identify the specific type of ink. As for the composition of ink and adhesive, Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), pyrolysis gas chromatography, and mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) was carried out on ink samples. The purpose of employing multi-analytical techniques is to integrate and corroborate the analytical results, providing an overview of the ink’s composition and progressively addressing the question of its original recipe. The results offer detailed information on the ink processing of palm-leaf manuscripts and also yield valuable insights into this longstanding problem in the conservation of palm-leaf manuscripts.

This study concentrates on the ink of ancient palm-leaf manuscripts from Tibet for the first time, and a multi-analytical approach is applied to analyze the composition of ink, which ultimately contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of ink-making processes, elucidates the mechanisms of ink degradation, and provides scientific support for the conservation and restoration of precious palm-leaf manuscripts.

Results

Optical microscope observation

Under the microscope, it is clearly observed that the ink on the sample surface exhibits good overall fluidity and opacity (Fig. 1), with ink particles adhering to the palm leaves and the text is mostly legible. However, the ink does not adhere strongly to the support, and it fails to penetrate the interior of the palm leaves. As a result, ink particles are missing in certain areas, allowing parts or the entirety of the surface previously obscured by the ink to become visible (Fig. 2). Ink loss, typically occurring along the horizontal fiber bundles, causes a faded appearance. This may result from factors intrinsic to the composition of the medium itself or from external environmental influences, including the characteristics of the writing support and mechanical friction encountered during handling. Additionally, a small amount of sediments are observed on the surface of the ink.

Partial fragments of the same numbered Tibetan palm-leaf manuscripts.

Digital microscope images of the surface of one of the ink sample fragments.

Raman analysis

The type of ink can be verified further with Raman spectroscopy analysis. Raman spectroscopy as an ideal non-destructive technique, has been widely used to characterize the the chemical composition of carbonaceous matter11. Three testing spots on two samples from the same numbered manuscript were analyzed, and the results showed consistency. Compared to the Raman results of the support material, the spectrum of the ink sample exhibited distinct peaks. The representative spectrum of the amorphous carbon was characterized by a broad peak of approximately 1350 cm−1 (designated as the D band) and a narrower peak of ~1585 cm−1 (designated as the G band)12. The Raman spectrum of the ink in Fig. 3 shows two bands at 1346 and 1590 cm−1, which unequivocally characterize amorphous carbon. However, the carbon-based ink exhibits similarities in the Raman spectrum, posing a challenge for further differentiation of the ink source.

The Raman spectrum from ink and support sample.

SEM–EDS analysis

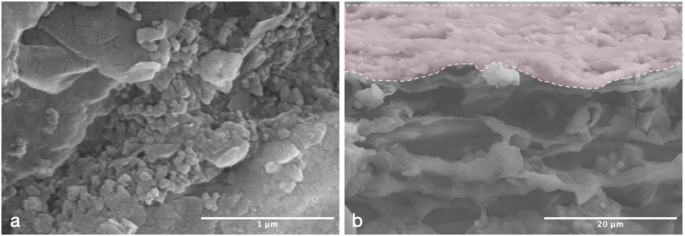

SEM–EDS analysis was used to obtain information about the size and morphology of the ink particles. This analysis was conducted on both the support and ink areas of two fragments from the same numbered manuscript, with a total of four tests performed. As shown in Fig. 4a, the partial flaking of adhesives in ink revealed ink particles in certain areas. In contrast, other areas of the ink exhibited characteristics of a coating-like layer covering the surface of support, attributable to the presence of adhesives. The SEM micrograph (Fig. 4a) of the ink area clearly showed that some particles with smooth surfaces were adhered to the surface of palm-leaf manuscripts. These uniform spherical particles with a diameter of about nanometer tended to join together, which is similar to the particle morphology of flame black described in the literature13. The flame black is a type of non-crystalline carbon produced in the gas phase, primarily consisting of lampblack and other forms of soot. The carbon particles within the flame inherently exhibit a property of poor dispersibility. Coupled with the presence of adhesives in the ink, this makes it challenging to distinguish the size of the joined carbon particles, necessitating further observation through TEM. Besides, the SEM image of the cross-section of the ink sample was shown in Fig. 4b, the cross-section image revealed the ink layer adhering to the surface of the palm leaf, showing a clear boundary and some gaps between the ink and the support. This indicates that the ink did not penetrate into the support but instead primarily attached to the support by the introduction of adhesives.

a The surface of ink sample b The cross-section the ink sample.

The elemental distribution of the surface of the ink sample was confirmed by SEM–EDS and the test results of ink and support were respectively shown in Figs. 5 and 6. Carbon (C) was the predominant element on the surface of the ink sample, followed by oxygen (O) and silicon (Si), with trace amounts of chlorine (Cl), aluminum (Al), potassium (K), sodium (Na), magnesium (Mg), and nitrogen (N) also detected. Upon further observation, it was evident from the elemental distribution shown in Fig. 5 that, apart from the carbon distribution, the concentrations of other elements are both low and evenly dispersed. These characteristics strongly indicated that the other elements mainly originate from the support. In addition, the surface of the support primarily contained carbon (C), oxygen (O), silicon (Si), nitrogen (N), aluminum (Al), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), and potassium (K). Notably, gold (Au) detected on the sample surface is due to an ultrathin conductive metal coating, typically applied before capturing SEM images. The silicon (Si) detected in both the ink and support are derived from the palm leaves’ surface. It has been reported that relatively high amounts of silicon have been found in the mesophyll cell walls of other species of palm leaves and these silica bodies serve multiple functions, not only enhancing the mechanical strength of leaf cells but also increasing the abrasion resistance of the cell walls, thus protecting the leaves from external damage14,15. Other elements at lower levels, including iron sodium (Na), magnesium (Mg), aluminum (Al), and potassium (K), were detected in both the support and ink sample, which are likely contaminants on the surface or possible interferences from intentionally added compounds16. Specifically, it could be observed that elements such as aluminum (Al), magnesium (Mg), and silicon (Si) exhibit corresponding spatial distribution characteristics at specific high-concentration points, highlighted by red boxes in Fig. 6, which suggested that the particles observed in the SEM morphology may be contaminants derived from montmorillonite.

EDS elements mappings and EDS spectra of ink sample.

EDS elements mappings and EDS spectra of support sample.

TEM analysis

It is commonly acknowledged that carbon-based ink can be produced by collecting the combustion of lamp soot, essence oil, resin, or tar et al17. Regarding the ink processing method of palm-leaf manuscripts, it is worth noting that the main source of carbon-based ink includes lamp soot10 and powder of charcoal2. The former, as one of the oldest pigments came from burning oil in lamps or pans, whereas the latter is the product of incomplete combustion of wood or wood raw materials. Past studies showed the lamp soot size distribution is smaller and more even than powder of charcoal from pine, which reveals very important information about the identification of ancient ink types18. To investigate the specific type of ink sample, TEM was applied to evaluate the primary particle size and morphology of the ink using one fragment as the test sample, with multiple observations and measurements conducted at different magnifications. It was clear from TEM images in Fig. 7 that the particle size was relatively uniform spherical, with all particles within about 50 nm range, and no indication of bimodal distribution. The TEM results are consistent with the particle morphology and size of lamp soot reported in the literature, thus confirming its identification as lamp soot19.

TEM images of the ink sample.

Pyrolysis-GC/MS analysis

Py-GC/MS analysis was separately conducted on the ink and support areas from one fragment. As shown in Fig. 8, the main compounds identified in the support sample can be categorized into two groups: (1) toluene and a small amount of nitrogen-containing organic compounds, indicating the presence of proteins; (2) a series of alkanes (including eicosane, hexadecane, nonadecane, octacosane, tetratetracontane, and heneicosane), along with minor amounts of long-chain alcohols and lipids, suggesting the presence of lipids and waxes. The total ion chromatograms of the ink sample were obtained in Fig. 9, while the primary compound information was listed in Table 1. The results indicated that four types of substances were detected in the ink sample: (1) a small number of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) such as pyrene, which was the demonstration of certain soot combustion20; (2) a series of compounds from protein including 1H-Pyrrole, 1-methyl-21, pyrrole22, toluene23, 3-methyl-indole. To further clarify the source of protein, comparing the result with the support sample, although the limited number of protein markers, toluene was also detected in the support sample analysis. This indicates that both the ancient palm leaf and ink samples contain proteins with the protein compounds identified in the ink sample being relatively more abundant. Moreover, since common proteinaceous materials, such as bone glue and leather glue are rich in proline, the presence of pyrrole (peak #2), formed through the dehydrogenation and/or dehydration of proline and hydroxyproline residues, confirms that the adhesive used in the ink may have originated from bone or leather glue24. In addition, methyl indole was considered the primary pyrolysis product of tryptophan and has been reported in the literature as potential evidence for the presence of egg glair compounds25. However, due to the limited number of samples, this inference remains tentative and requires further validation through additional data and complementary analyses; (3) marker compounds from polysaccharide could be identified in ink sample as follows: Benzofuran, 2-methyl-, maltol, 1-Hydroxy-2-butanone, and 2-cyclopentene-1-one, which were identified as the characteristic pyrolysis products from plant gum26,27. Additionally, no typical pyrolysis products of starch were detected in either ink and support samples; (4) fatty acids containing palmitic acid and stearic acid, as well as alkanes, including tetracosan and heptacosane, were also found in low amounts. According to the literature, these compounds are derived from the oils and waxes on the palm-leaf surface10.

Total ion current chromatogram of support sample. C Alkane, An long-chain alcohols, Ln long-chain lipids, N nitrogen-containing organic compounds.

Total ion current chromatogram of ink sample, the peak numbers refer to the assignations in Table 1.

FTIR analysis

In order to easier interpret the ink composition, a comparison between the spectra of the ink sample and support sample was depicted in Fig.10. The spectra of the ink and support both confirmed the presence of protein, with the prominent signals of the amide group (–N(H)–C = O–) near 1650 and 1550 cm−1. Specifically, the peak near 1650 cm−1 corresponded to the C = O stretching vibration region, and the peak at around 1550 cm−1 was assigned to the N–H bending vibration region28. These results are also consistent with the protein peaks detected by Py-GC/MS analysis, suggesting the presence of proteins in adhesive, likely originating from bone or leather glue. It was worth noticing that the absorption peak near 1733 cm−1 observed in both the ink and support samples was attributed to the ester group, and the peaks at 1240 and 1163 cm−1 in the ink sample were further confirmed as corresponding to ester and acid groups29. The peaks at 1161 and 1467 cm−1 could be ascribed to triacylglycerol-specific signals, which represent the presence of fat and oil on the surface of the sample30. These peaks were visible in the spectrum of ink and support but were more obviously intensive in the support sample. Absorption peaks near wave numbers 2861 and 2933 cm−1, respectively, correspond to C–H stretching and CH2 stretching, which could be identified clearly in the ink and support sample. These two bands were associated with polysaccharides, suggesting that cellulose and hemicellulose are present in the palm-leaf manuscripts, while polysaccharides such as gum were used as adhesives in the ink10. Additionally, the strong band near 3381 cm−1 observed in two samples was due to the free –OH stretching from cellulose31. The peak absorptions around 1515 and 1425 cm−1 suggested the aromatic skeleton vibrations of ligins32.

FTIR spectra of the ink and support sample.

Discussion

Microscopic observation and cross-sectional SEM analysis revealed that the ink remained on the surface of the support, without penetrating into the internal structure of the palm leaves. Additionally, some sediments were observed on the ink surface, providing a rational basis for subsequent elemental analysis. Raman spectroscopy confirmed that the ink on the palm-leaf manuscript was carbon-based and SEM–EDS further verified that carbon was the primary chemical element in the ink, aligning with findings from the literature review. A systematic review of existing research on palm-leaf manuscript ink-making techniques revealed that carbon black was used as the primary pigment in palm-leaf manuscripts. According to historical records, ink preparation involved materials with a wide range of origins, notably including ashes from burned wood and soot from cooking pots or lamps33. Current scientific analysis of ink samples from ancient palm-leaf manuscripts remains limited, and further exploration is needed in this study to confirm which of the above types this ink belongs. TEM analysis of the ink particles further revealed that the morphology and particle size closely resembled lampblack, indicating that the ink may originate from the combustion of oils, thus providing direct evidence of the source of ink used in ancient Tibetan palm-leaf manuscripts. Additionally, some sediments were observed on the ink surface, identified as montmorillonite contaminants. Elemental analysis suggests that the nitrogen element may originate from proteins in the ink adhesives.

To further investigate other components in the ink, such as adhesive, FTIR and Py-GC/MS analysis were conducted. Both results consistently identified polysaccharides, suggesting the presence of plant gums in the ink. These findings align with historical records that mention the frequent use of plant-based adhesives in ink preparation. Although proteins were detected in both the ink and the support, Py-GC/MS analysis showed that proteins were more abundant in the ink, indicating the possible use of animal glue. Animal glue is derived from boiling the skin, bones, or cartilage of mammals and fish and is primarily composed of proline34. The abundant pyrrole compounds are associated with proline in bone glue and leather glue, further suggesting that the adhesive may contain materials such as bone glue or leather glue. Lipids were also detected in both the ink and the support, suggesting the addition of oils such as sesame or almond oil to prepare an oil-based ink3. Nevertheless, due to sample limitations, the precise origin of the lipids remains indeterminate, indicating the need for further investigation. Notably, no characteristic starch substances were found in either the ink or the support, suggesting that starch paste was not used in the ink preparation.

The findings provide direct scientific evidence for the ink-making techniques of ancient palm-leaf manuscripts, effectively supplementing and enriching incomplete historical records. This study is thus significant in advancing the understanding of ink composition and the origins of ancient Tibetan palm-leaf manuscripts.

Conclusion

In this study, the ink of the palm-leaf manuscript has been characterized by optical microscope, Raman, SEM–EDS, TEM, Py-GC/MS, and FTIR. Based on the discussed results, we concluded that the ink type of the palm-leaf manuscript was identified as lamp soot, and the ink particles attached to the support by the introduction of adhesives through Raman, SEM–EDS, and TEM. Py-GC/MS analysis combined with FTIR brought new and informative data on the organic materials in ink. Proteins and lipids were detected in both the ink and support samples, while in the ink sample, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH), proteins, pectin, fats, and polysaccharides were identified, with proteins and polysaccharides showing higher intensities. This suggests that animal glue such as bone glue and leather glue, pectin, and polysaccharides were used as adhesives in the ink. The scientific data obtained in this study are a crucial contribution to the previous research on palm-leaf manuscripts, addressing key questions about the composition of ink of palm-leaf manuscripts which can provide an important reference for further understanding the ink-making process and revealing the mechanism of ink disease of ancient palm-leaf manuscripts. Due to the limited number of samples in this study, the composition of the ink was determined through the multi-analysis of typical ink samples. If more samples can be obtained in the future, further analysis could yield more valuable information. Furthermore, a comprehensive technical analysis of more samples from different periods and regions will undoubtedly deepen our understanding of the ink preparation techniques used in palm-leaf manuscripts.

Materials and methods

Samples description

Influenced by the transmission paths of Tibetan Buddhism, the Tibet region has preserved the largest collection of palm-leaf manuscripts in China. These Sanskrit palm-leaf manuscripts in Tibet primarily originated from regions such as Nepal, India, and Kashmir, where Buddhism flourished from the 7th to the 13th century35. Notably, the highest number of palm-leaf manuscripts was found in the period from the 10th to the 13th century. Currently, palm-leaf manuscripts in the Tibet region are primarily concentrated in the Tibet Museum and various monasteries. These palm-leaf manuscripts are predominantly recorded through writing on the surface, encompassing valuable content such as Sanskrit grammar, poetry, astronomy, and Buddhism, thereby possessing significant academic value and historical importance.

The ink samples in this study were from several fragments of ancient palm-leaf manuscripts preserved in the Tibet region. Due to the distinct characteristics of scripts from different periods of ancient India allow for the dating of their formation based on these features. Combining the script characteristics of the manuscript, it can be identified as an Eastern Indian script. The formation time of the palm-leaf manuscript is estimated to be in the 12th–13th centuries, and not later than the 14th century. Given the dry climate of the Tibetan region and the lack of targeted preservation measures, the manuscript exhibits significant embrittlement and is highly prone to fracturing. To ensure result consistency, five naturally detached fragments from the same numbered manuscript were selected for follow-up analysis. The non-destructive tests were conducted on two samples as shown in Fig.1. Most of the ink on the samples is relatively clear, however, some exhibit characteristics of ink deterioration, such as fading and blurring. Therefore, analysis tests were conducted on the collected samples according to the preservation condition of the ink. Specifically, a non-invasive test was performed at points where the ink was relatively concentrated and clear. Additionally, three smaller fragments with visible ink from the same manuscript were selected for destructive analysis.

Experiments and instruments

Microscope observation

In order to assess the current condition of the ink sample, the microscope observation was carried out using non-invasive in situ techniques to perform surface observations of ink samples containing the support. Dino-Lite AM4115T portable digital microscope (Anpeng Technology Co., Ltd., China) was used to observe the morphology of ink on the palm-leaf manuscripts and ReView Pro-200 portable digital microscope measuring instrument (Guangdong Fuchi Technology Co., Ltd.) facilitated high-magnification observation of the ink preservation condition.

Raman spectroscopy

The ink and support areas of the ink sample were analyzed with the Horiba XploRa Plus Raman spectrometer (HORIBA Trading Co., Ltd., China) equipped with a microscope for precise positioning. The parameters were kept at the green laser (638 nm), at ∼8 mW with 25% laser power to avoid damaging the sample with the laser, 2 s exposure time, and 20 scan accumulation, and the spectra are recorded in the range of 1000–2000 cm−1, with a 1200 l/mm grating. The spectra were baseline-corrected to remove the noise.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive spectrometry (EDS)

The collected fallen sample fragment containing ink was fixed onto a conductive carrier and made conductive by sputter-coating them with a gold–palladium alloy for 30 s. Then the ink and support areas of the ink sample were separately observed by Hitachi SU8010 scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi Ltd., Japan) and Bruker XFlash 660 energy dispersive spectrometry (Bruker corporation, USA) for recording the microscopic surface morphology, element distribution mapping, and element contents of ink and support. The acceleration voltage during the analysis was 15 kV, and the current was 10 μA.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The fragment containing ink was partially prepared for cutting the ultrathin section by Leica EM UC6 Ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems Trading Co., Ltd., Shanghai). After that, the JEM-2100F Field-emission high-resolution transmission electron microscope (Japan Electron Optics Laboratory Co., Ltd., Japan) was applied to observe the microscopic morphology of carbon particles. The images were photographed at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV, with a magnification of ×200k and an exposure time of 0.638 s.

Pyrolysis gas chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis (Py-GC/MS)

The fragment with clear and concentrated ink, as well as support fragment, were selected for analysis. Due to the difficulty of separating the ink from the substrate, a 0.91 mg ink sample containing the support, along with a support-only fragment was chosen for testing. GC–MS analysis was performed by EGA/PY-3030D pyrolyzer (Frontier Lab, Japan) attached to the GCMS-QP2010Ultra gas chromatography–mass spectrometer (Shimadzu, Japan). A DB-5MS column (5% diphenyl/95% dimethyl siloxane) with a length of 30 m, an inner diameter of 0.25 mm, and a film thickness of 0.25 μm (Supelco, USA) was used to separate components. The samples, each placed in a sample cup, were separately conveyed into the furnace via the autosampler, following which the temperature protocol of the GC/MS was initiated. Pyrolysis was carried out at 600 °C and the Py-GC interface was held at 300 °C. The initial temperature of the oven was at 70 °C for 2 min, followed by a ramp to 280 °C at a rate of 20 °C min−1, and then held for 20 min. Helium was used as the carrier gas with a flow rate of 1 mL min−1, and used in split mode (1:50 of the total flow). The mass spectrometer was operated at 70 eV and scanned from m/z 29–550 with a cycle time of 0.5 s.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The infrared spectra were recorded with an Agilent 4300 handheld FTIR spectrometer (Agilent Technologies Co., Ltd., China) using Diffuse reflectance (DRIFTS) mode. The spectra were measured at room temperature from 4000 to 650 cm−1 with a wavenumber range and a resolution of 4 cm−1. The selected sample testing points, including both the ink and the support, were analyzed for non-destructive contact testing and the examination was done by using an infrared instrument to identify the main composition of ink.

Responses